To See More Clearly and Broadly: Science and the Postmodern Sentiment

To See More Clearly and Broadly: Science and the Postmodern Sentiment |

"The end of man is to know."

Robert Penn Warren, All the King's Men

<1> What we call "postmodernism," whether we refer to the sciences or the humanities, is a certain preoccupation with the role of the human observer in the composition and perception -- perhaps even construction -- of reality. The postmodern condition, so to speak, is the moment in history when the "hard" sciences and the sciences of man seem to be suffering from the same anxieties about the relevance of the self-reflexive interaction between the observer and the subject to the fabric of existence and the web of knowledge. In simplest terms, we would define the postmodern question as this: "How much do I affect that which I observe?" More broadly the question becomes "What role, if any, does observation itself play in the universe?"

<2> As one of us suggested in Reconstruction 2.1 "The path of observation is the most fundamental and accessible route in the project of a mutually supporting theory between the disciplines. Primary to the goal of observation is the exploration of borders, boundaries and so-called 'givens,' and most importantly, anything constructed as 'natural'" [1]. This is that "rare and narrow passage" discussed by Michel Serres between the sciences and humanities [2].

<3> Much of the science discussed here, and indeed much of the science we might (correctly or incorrectly) label "postmodern" may be described as the sciences of Alpha and Omega, or beginnings and ends. Thus we can see the three functions of science in its historical, descriptive and predictive roles: how things began, how they are, and how they will be.The Alpha theories of the Big Bang, for instance are necessarily tied to the Omega theories of the last days of the Universe, for in the beginning the end is written. No wonder philosophers and theologians have taken an increasing, and often unwelcome, interest in the sciences over the last century; science seems to be rapidly closing in on the traditional territory of both philosophy and theology waving high the banners of GUT [3]and TOE [4] with rallying cries of "chaos," "omega point," "the birth of a star," and "seeing the face of God."

<4> Many scientists who now cringe at the very mention of the phrase "Chaos Theory" just as Erwin SchrąŹdinger implied that he seriously regretted ever coming up with the now infamous cat in a box[5]. It is now more proper to use the more genteel term "complex dynamics" in mixed company. Nonetheless, popular science is just that: the science of the populace, the science the common layperson understands, the science they are interested in, the science that they support at the voting booth, at the box office, on television, and at the news stand. Here are the titles that grab our attention: Jurassic Park, Contact, The Elegant Universe, Chaos, A Brief History of Time, SchrąŹdinger's Kittens and the Search for Reality, AI, The Golem, The End of Science, The Matrix, The Anthropic Cosmological Principles, The Physics of Immortality, The Number of the Beast, Me++, etc. Our subjects are cloning, complex dynamics, multiple universes, time travel, the big bang, the end of the universe, artificial intelligence, string theory, cyberspace, spooky action, and in some cases nothing less than eternal life and the resurrection of the dead through the wonders of technology and computing. Some scientists might prefer a little less attention, a bit more sober discussion of theory and less of the highly paid, high glitz television sponsored popularizes and yet the money keeps rolling in for those popular fields at the same time that it dries up for unpopular ones. Many of us remember Stephen Hawking playing cards with Worf and Data on Star Trek: The Next Generation. In the long run, science has not suffered from its popularity.

<5> Popular science in a postmodern era is a postmodern science: not because the most basic methods of science have changed (they have not) but because the way those methods are perceived have changed and the new technologies used have made available a wider range of experience for the scientist and layperson alike. From somewhere within the complex system of observer, observed, and the technology of the observing tool, or apparatus, arose the realization that to look and to know was not simply to interiorize an external reality but also, in some sense, to potentially modify that reality. The affect of the observer may ultimately be dismissed as infinitesimally small (or arguably non-existent) as in the case of observing a supernova from Earth that happened millennia ago, but the role of the observer must, nevertheless, consciously be considered before being dismissed. This has always been the basis for experimentation, after all: repeated experiments reduce the impact of the variables including the observer. What in Marx's terms we called "bodies," "tools," and "the world" have now become a complex dynamical system composed of "observers," "subjects," and "apparatus."

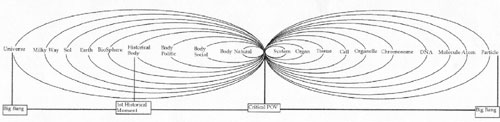

<6> These are the terms of our collective postmodern endeavor. The only appreciable difference is on what scale the observer interacts; even then, as we can see in the following, the farther one moves up or down the scale of observation the closer one moves to the opposite scale in time. Thus, the observers of the smallest (quanta) and largest (Universe) are dealing with material originating in the Big Bang.

The Body Observer Model (click to enlarge) [6]

<7> We all occupy multiple positions on this scale of observation and partake of all of them. Postmodern science is, in a word, a science of perspective. Unlike the gentleman science of the Enlightenment or the secret science of the Cold War, postmodern science is ours and it is a collective endeavor to see more broadly and clearly.

We offer the essays included here to that end.

The Editors.

C. Jason Smith and Robert Froemke

Notes

[1] "The Observing Body: Quantum Mechanics, the Anthropic Principles, and Panopticism" (Reconstruction 2.1 [Winter 2002]). [^]

[2] Michel Serres, Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy, Ed. Josuą© V. Harari & David F. Bell. (Baltimore : Johns Hopkins UP, 1982) 18. [^]

[3] Grand Unified Theory. [^]

[4] Theory of Everything. [^]

[5] See, for example the epigraph of John Gribbon's In Search of SchrąŹdinger's Cat: Quantum Physics and Reality (New York: Bantam, 1984). [^]

[6] "The Body Observer Model" is from Christopher Jason Smith, The Body Complex in Contemporary Science, Literature, and Culture (Thesis [Ph. D.] -- University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1998). [^]