A More Complete Ahab: Into the Darkness of Moby-Dick

by Andrea Modarres and Ellen M. Bayer

Introduction: The People’s Ahab: The Pervasiveness of Ahab and the White Whale in Popular Culture

“to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee; for hate’s sake I spit my last breath at thee’— Moby-Dick, “The Chase—Third Day”

<1> Over 100 years after its publication, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick occupies the rare position of true cultural icon, one of those important novels that people know about without ever having read it. References to the white whale and the captain who chases him surface in an almost endless stream of high art and pop culture artifacts and references. A list of just a few of the many Moby-Dick-inspired texts includes operatic, film, comic, and graphic novel adaptations; New Yorker and television cartoons (Tom and Jerry’s “Dicky Moe” is one of the more obvious); references in film (Zelig, Heathers, Fried Green Tomatoes, The Life Aquatic, Jaws) and television shows (The Simpsons, The X Files, Parks and Recreation); and musical tributes (Mastodon, Led Zeppelin, Moby Grape, Ahab). The names from the novel and images of the whale appear as marketing aids (seafood and kabob restaurants, a full-page Microsoft advertisement), while the text turns up in politics (prosecutor Kenneth Starr pursuing Bill Clinton), in football (Peyton Manning as Ahab seeking his White Whale—the New England Patriots), and on late-night comedy shows (Stephen Colbert’s recent rollercoaster interview with scholar Andrew Delbanco about what makes Moby-Dick the Great American Novel). Susan Weiner argues that “the white whale has become one of the few unifying symbols that Americans share. In a dazzling reversal of fortune, a complex artifact of high culture has transcended that category to become a popular icon. A classic text has crossed a border to forge a new frontier” (85). Despite this apparent cultural familiarity with the novel, however, most public and artistic references to Moby-Dick reduce it down to Ahab’s hunt for the white whale, reproducing instead a figure of the obsessed Captain Ahab stomping angrily on his peg leg and raving about the beast upon whom he desires revenge. Building on Richard Brodhead’s observation that American culture has “absorbed” Melville’s novel to the point that even those who have not read it are familiar with Ahab’s quest, Jeffrey Insko posits such understandings as cultural, not textual, knowledge. Insko terms the ubiquitous use of this metaphor “the Ahab trope,” claiming that “such references have been emptied of any and all associations with the text from which they are ostensibly drawn” (20). Perhaps this loss is inevitable when the source text is as complex as Melville’s novel, but the Ahab trope has achieved such familiar cultural status that it stands on its own as an original artifact, one that is adapted and reinscribed with little or no relationship to Melville.

|

|

<2> The Ahab of popular culture is one-dimensional, effective as an icon because it represents an all-too familiar impulse for revenge. Despite countless religious and moral teachings that urge us to forgive our enemies, the desire to enact revenge for our injuries is a powerful and relatable impulse, perhaps because it has roots in our biological makeup: according to many current studies, psychiatrist Sandra Bloom argues, “vengeance is part of the innate survival mechanics of a complex social species. The desire for vengeance is as old – or older – than humankind” (61). Canonical literary explorations of the desire for and costs of revenge abound, from Homer’s story of the Trojan War and Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Othello to numerous stories by Edgar Allan Poe and scores of current horror films, illustrating how strongly this topic resonates. Bloom points out that “Human beings evolved in a hostile evolutionary context, one in which we were a relatively powerless and defenseless animal surrounded by predatory beasts. In the face of this reality, acts of revenge became a source of power and mastery for a species conditioned through millions of years of experience to being the helpless prey of other, larger and hungry beasts” (65), leading to the question of how to overcome this biological conditioning as humanity evolves as a species. Despite, or perhaps because of, the apparently inherent nature of our desire for vengeance, moral, religious, and philosophical arguments about how to control and channel retribution in socially acceptable ways have preoccupied philosophers and ethicists over the centuries, from Francis Bacon’s assertion that “Revenge is a kind of wild justice; which the more man’s nature runs to, the more ought law to weed it out” (“Of Revenge”) to John Stuart Mill’s observation that while “It is natural to resent, and to repel or retaliate for, any harm done or attempted against ourselves . . . it is certainly common enough— though the reverse of commendable—for someone to feel resentment merely because he has suffered pain” (35). The Ahab trope is relatable, even its exaggeration, because the infamous whaler’s pain and anger stem from a desire that most of us can understand, if not condone: the almost reflexive impulse to hurt the person or thing that has caused us to suffer. Adaptations of Melville’s novel often focus precisely on this most familiar preoccupation with revenge, and on some representation of the white whale as the object of vengeance, frequently relying on generalized cultural knowledge of the Ahab trope because of the work it does as thematic shorthand, instead of a deeper textual engagement with the full scope of Melville’s novel.

<3> In this article, we focus on how several films have adapted the novel with varying degrees of success, examining how adaptations are least effective when they merely attempt to copy the original written text into the different form of film, and most effective when they stand on their own as new works of art that translate some truth about themes in the source text. Adaptation theorist Linda Hutcheon defines adaptations by positioning them as palimpsests, explaining, “When we call a work an adaptation, we openly announce its overt relationship to another work or works . . . created and then received in relation to a prior text” (Theory 6). In translating a classic novel such as Moby-Dick into different media forms, such as film, cartoon, graphic novel, or television show, traces of the original linger, but contemporary cultural frames of reference will inevitably color the form of the new creation, just as Melville’s novel reflects his socio-historical context. As Daniel Fischlin argues, “media are themselves always already cultural – they embed and embody symbols, values, aspirations, imagination, narrative, semiotics, and technologies that arise from specific sets of circumstances” (7). In examining the various ways that the Ahab trope has traveled from novel to film, it is important to conceptualize how the move from one type of media to another inevitably entails a reconfiguration of the content of the original, including the extent to which explorations of revenge drive the characterizations, structure the storylines, and influence audience responses. Hutcheon argues that the term “adaptation” must encompass not just the product and the process of adaptation, but also the reception: in other words, viewers engage with “adaptations as palimpsests” due to “our memory of other works that resonate through repetition and variation” (Theory 8). Therefore, analyzing adaptations requires that we consider how our responses to the newer versions rely upon some kind of knowledge of the original source, and in the case of Moby-Dick, the Ahab trope often stands in for the entire novel, reducing the character of Ahab to his obsessive quest for revenge, and creating a referential loop that frequently works to lessen the power of the source material. What the use of the trope reinforces, nevertheless, is a continuing preoccupation with the need for revenge, as well as its consequences.

<4> Three films in particular exemplify a variety of approaches to adapting Melville’s novel, and in their attempts to explore revenge as a theme, illustrate its perennial relevance: John Huston’s 1956 movie of the same name, and two of the popular Star Trek films, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982) and Star Trek Into Darkness (2013). We first compare Melville’s source text to Huston’s film in order to establish a frame of reference for how a too-literal adherence to the novel leaves little room for viewers to engage with the film on its own terms, and then examine how the two Star Trek films succeed as adaptations to a lesser or greater extent. Rather than critiquing the changes made between text and films, we analyze the ways the resonance of the novel translates into film. The character study in Wrath of Khan, which draws heavily upon themes in the novel in order to meditate upon friendship, aging, and mortality, in addition to the costs of revenge, is largely lost in Into Darkness; this film is not so much an adaptation of Moby-Dick the novel as it is of its 1982 filmic predecessor, functioning instead as an all-too-obvious allegory for obsessive vengeance and relying extensively on the Ahab trope as it moves farther away from Melville’s text.

<5> The Star Trek franchise, which occupies its own niche as popular culture icon, has drawn heavily upon Melville’s book ever since its inception in the 1960s, illustrating the ways that the character of Ahab acts as a potent cultural icon for the costs of revenge. Audiences watching the show and films may not have read Melville’s novel, but the Ahab trope survives as its trace and remnant, through which they will understand new meditations on similar themes. The move from Melville’s vast aquatic environment to Star Trek’s final frontiers entails a number of adaptations (including episodes of the original television show and The Next Generation) that in some cases move so far away from the deeper themes in the novel that they become mere gestures toward their literary inspiration.

<6> A variety of scholars explore the adaptive strategies of these new visions of Moby-Dick. As Hutcheon points out, some “responses to prior stor[ies]” fail as adaptations because they do not allow the audience to engage with the traces of their sources, lacking what she calls the “oscillation between a past image and a present one” (Theory 172). The 1982 and 2013 films most clearly exemplify the power of the Ahab trope to rewrite Melville’s character in our cultural consciousness, but they do not draw in the same way on the reflectiveness of Melville’s text. Denis Donoghue provides a justification for the endurance of the Ahab trope, asserting that “no book stays in one’s mind as a whole. We remember fragments of it, not necessarily the most fundamental” (186), and surely the crazed Ahab bent on revenge is the most vivid and robust fragment of Melville’s novel in the wider cultural context today, with his eminently human desire to make the whale pay for his injuries. Hutcheon points out that “Transposition to another medium . . . always means change or, in the language of the new media, ‘reformatting’” (Theory 16), and those versions of Moby-Dick that fail to reformat themselves within a meaningful framework fall flat as adaptations. Elizabeth Schultz makes a similar argument in regards to abstract art and book illustration, positing that artists who have created abstract expressions in response to Melville’s novel have enjoyed more freedom to explore its complexities precisely because they are not tasked with reproducing a representative, narrative scene—what Michael Melot calls “the critical moment” or what Edward Hodnett terms “the moment of choice” (Schultz 15). While none of the films captures the full sweep of the novel, The Wrath of Khan comes closest to passing Hutcheon’s “test” of a successful adaptation: one that is “palimpsestous,” perhaps repeating the original text in its thematic focus, but avoiding the trap of mere imitation. This film successfully manipulates what Hutcheon terms “the comfort of ritual” in its use of the Ahab trope to represent revenge, but it adds “the piquancy of surprise” (Theory 4) because it expands upon the trope to evoke the novel and meditate upon aging and friendship and explore the costs of revenge. As an adaptation of Melville, it asks what it means to be human, moving beyond the simple trope and creating a more complete Ahab.

Herman Melville’s Captain Ahab

“‘Ahab has his humanities!’” –Moby-Dick, “The Ship”

<7> Turning first to the novel to examine Melville’s portrayal of his iconic character serves to liberate him from the shackles of “the Ahab trope.” Of course, representations of Ahab as the monomaniacal, obsessed captain do not emerge from a vacuum; the text certainly paints him as a man with tunnel vision, dead set on revenge against the whale that took his leg. Ahab stands upon his quarterdeck and calls his men to join him in his quest, foregoes the pleasantries of a game with passing ships because it will slow his progress, baptizes his harpoon in human blood, and rushes his men toward the open jaws of an enormous and aggressive sperm whale in the name of conquering his foe—to name only a few moments in which we see Ahab earn his reputation as “madness maddened” (184). This side of Ahab is the one responsible for the power of the Ahab trope as a representation of revenge. Focusing only on these moments, however, neglects the nuance of Melville’s layered captain. He becomes a mere stick figure, a one-dimensional archetype onto which we can project generalizations about the nature of revenge and obsession. To know a more complete Ahab, we must heed the words of Captain Peleg, an owner of the Pequod, to Ishmael: “‘wrong not Captain Ahab, because he happens to have a wicked name…. stricken, blasted, if he be, Ahab has his humanities!’” (98).

<8> Just as the Ahab trope lives in popular culture without relying on in-depth knowledge of the novel, Captain Ahab’s reputation as a strong commander precedes him even though he does not appear in the flesh until Chapter 28 of Moby-Dick. Unlike the trope’s emphasis on his physical disability, in the book his bodily presence stuns Ishmael at first sight. Ahab strikes the narrator as “a man cut away from the stake, when the fire has overrunningly wasted all the limbs without consuming them, or taking away one particle from their compacted aged robustness. His whole high, broad form seemed made of solid bronze and shaped in an unalterable mould, like Cellini’s cast of Perseus” (138-9). Ishmael presents a powerful image of a man who has withstood engulfing flames, marked by them yet not diminished “one particle.” The classical allusion to Cellini’s statue further reinforces the respect Ahab’s physical being demands: Cellini’s Perseus stands triumphant over the slain Medusa, his muscles rippling and suggestive of sheer physical force. The lightning bolt-shaped scar that “tearingly darts down” Ahab’s face arrests Ishmael’s attention and elicits all manner of speculation on the part of the crew (139). Indeed, he is so dumbstruck by the captain’s “whole grim aspect” that Ishmael does not at first notice Ahab’s white leg fashioned from whalebone—the feature otherwise most commonly associated with him (139). From an episode of the animated Tom and Jerry show to any number of New Yorker cartoons, the sea captain with a peg leg has become shorthand for Ahab in our cultural consciousness, but Ishmael’s first impression reveals a more imposing, physical “robustness” that is lost in later representations.

<9> While the Ahab trope relies on an image of the mad captain pounding the decks with his peg leg, Melville’s captain is mindful of the distraction such stomping would create for his crew. Ishmael notes that, just as the sailors on the night watch are careful not to make noise out of respect for the sleepers below, so, too, does Ahab keep his men in mind when he curbs his intense desire to pace the deck at night: “Some considerating touch of humanity was in him; for at times like these, he usually abstained from patrolling the quarter-deck because, to his wearied mates seeking repose within six inches of his ivory heel, such would have been the reverberating crack and din of that bony step, that their dreams would have been of the crunching teeth of sharks,” and it is only on one occasion that “the mood was on him too deep for common regardings” (142). Knowing the repeated click of his whalebone leg will interrupt the men who sleep inches below him, Ahab reins in his pacing, and it is only in a moment of complete distraction that he neglects this courtesy. Alone with his troubled thoughts, and in such a confined and isolating space as a whaling ship in the heart of the sea, Ahab paces the deck as a means of expelling his anxieties. To take into consideration the welfare of his crew, and deny himself this bit of solace, speaks to the captain’s general concern for the men who share this space with him. This subtle moment of Ahab’s thoughtfulness reveals his human side. It is an especially important moment to consider because, as we shall see below, film adaptations portray Ahab’s steady stomp upon the night watch deck as a regular feature that keeps his men awake, not as the rare exception that it is.

<10> The Ahab who inspires the trope that eventually follows in his wake appears in the infamous “Quarter-Deck” scene, in the chapter of the same title. This is the moment in which Ahab reveals his intention to hunt and kill Moby Dick, a scene that eventually devolves into a manic initiation ceremony fueled by the blind allegiance that Ahab ignites in his men. He draws them in closer by waving a gold doubloon in their faces as he announces that whoever spots Moby Dick first shall win the coin. Having their attention and allegiance, Ahab seals the deal by passing around the ship’s grog to “the frantic crew” (182), intoxicated by the fraternity of their common oath and the alcohol alike. They pledge to follow Ahab, who vows that he will “‘chase [Moby Dick] round Good Hope, and round the Horn, and round the Norway Maelstrom, and round perdition’s flames before [he] gives him up’” (179). Only the first mate, Starbuck, resists the mob mentality of the scene, and asks the captain, “‘How many barrels will thy vengeance yield thee even if thou gettest it, Captain Ahab?’” (179). Ahab pounds his chest and declares that his “‘vengeance will fetch a great premium’” there (179). Starbuck cannot comprehend Ahab’s desire to enact revenge on what the first mate views as an unthinking animal that bit off the captain’s leg only out of sheer instinct. For Ahab, though, we learn that his anger goes deeper than this superficial motive, and his response articulates “the little lower layer” that torments him:

All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event — in the living act, the undoubted deed — there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ’tis enough. He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it. That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate; and be the white whale agent, or be the white whale principal, I will wreak that hate upon him. (179-80)

<11> The white whale, to Ahab, is not a whale at all. He is the physical manifestation of the mystery of the universe, the answer to the great meaning of life. Ahab feels that he is a prisoner of his own limitations—not limitations of the missing limb but of the mind and the soul. He must know that his life has meaning and purpose; he must know what invisible hand, if any, directs his fate. He must touch that which resides beyond human understanding, and his inability to do so infuriates him. The white whale snapping off his leg smacks him like an added insult. To liberate himself, Ahab must “strike through the mask” of the physical world in order to know the metaphysical. Some “reasoning thing” taunts him with its presence opposite the thin barrier of the mask, barely beyond his grasp. In reaching enlightenment and gaining understanding of the reason behind the whale’s “unmasting” of him, Ahab believes that he can come to know a greater truth about creation. He is prepared for there to be no divine being behind the mask, but it is the not knowing that “tasks” and “heaps” him, and he believes that his hunt for Moby Dick, and wreaking his vengeance upon what the whale represents in his eye, will assuage the torment of facing his own insignificance. As we discuss below, this scene, and Ahab’s words, echo throughout filmic reinterpretations of the novel. There is something universal in his longing for insight; Ahab not only voices the questions that many of us silently ponder, but he also actively pursues them. Perhaps it is this aspect of his nature that gives Melville’s captain a timelessness and resonance, but the trope is rarely addressed in the adaptations it inspires.

<12> If Melville’s adaptors gravitate to the “Quarter-Deck” scene, they invariably seem to skip over the chapters that succeed it. These aesthetic choices position the Ahab trope as the fragment of the novel that endures, obscuring the novel’s nuanced character study in favor of a narrow examination of the revenge quest. Melville, on the other hand, carefully constructs a captain at war within himself, grappling with the morality and the necessity of his hunt. In the chapter that immediately follows, “Sunset,” Ahab sits alone in his cabin and watches as the sun sinks below the horizon. It is the first of many moments of utter sadness for the captain; in this soliloquy, he despairs that the setting of the sun no longer comforts him: “Oh! time was, when as the sunrise nobly spurred me on, so the sunset soothed. No more. This lovely light, it lights not me; all loveliness is anguish to me, since I can ne’re enjoy. Gifted with the high perception, I lack the low, enjoying power; damned, most subtly and most malignantly! damned in the midst of Paradise!” (183). Emotionally wounded by his loss of limb, Ahab can no longer take pleasure in the simple joys of daily existence. The existential questions that plague his mind prevent him from finding comfort in the beauty of a sunset. This is a man who understands his predicament. He recognizes the ways in which his quest precludes him from living in peace and makes his life a daily hell. This sorrow is all too often lost in the superficial depictions of Ahab that follow in his “white and turbid wake” (183).

<13> As the voyage progresses, we see moments in which Ahab must resist being swayed from his purpose, often in response to the lure of thoughts of his home and family. One subtle moment quietly serves to prime Ahab to be moved by Starbuck in Chapter 132, “The Symphony.” As the gloomy Pequod meets the jubilant Bachelor, a Nantucket whaler homeward bound, Ahab removes a vial of sand from his pocket and looks back and forth between it and the receding ship. Ishmael reads this gesture as Ahab “bringing two remote associations together, for that vial was filled with Nantucket soundings” (508). It is notable that Ahab keeps this particular object on his person. At the start of his voyage, the captain tosses his pipe into the sea, recognizing that it can no longer bring him comfort. He holds fast to the vial of Nantucket sand, though, which speaks to the strong pull his home still has for him. It is yet another poignant and sad moment that illustrates the influence his family maintains, despite his monomania. Furthermore, it reminds us of the stakes of his revenge: not only can his quest for vengeance harm the crew of the Pequod, but it can also hurt Ahab’s family, and himself. When adaptations reduce the costs of Ahab’s quest to the sinking of a ship, they neglect to consider the broader consequences and costs of revenge.

<14> “The Symphony” chapter is crucial for revealing Ahab’s vulnerable side and reinforcing what he stands to lose as a result of seeking revenge against Moby Dick. The scene opens on a mild day, with Ahab looking over the rail into the gliding waves. Much as the first hints of warm weather nearly inspired a smile in him, here, too, does the “enchanted air…at last seem to dispel, for a moment, the cankerous thing in his soul” (552). Ahab’s musings, coupled with “[t]hat glad, happy air” that seems to hold and weep over him, elicit a single tear that drops into the sea: “nor did all the Pacific contain such wealth as that one wee drop” (552). Ahab may muster only a single tear, but the text is clear in the estimate of its value. The monologue that follows suggests the source of Ahab’s torment: he has spent forty years at sea conducting brutal and dehumanizing work in “the desolation and solitude” of a whaling ship (553). Losing his leg in a traumatic encounter with a sperm whale was simply the final straw that propelled Ahab on a quest for revenge against the unfairness of the universe. Ahab speaks to this in his question to Starbuck: “‘is it not hard that, with the weary load I bear, one poor leg should have been snatched from under me?’” (553). Looking into the “magic glass” of Starbuck’s eye, Ahab sees his own wife and child there, and the first mate nearly convinces him to give up the chase. Ahab must avert his gaze in order to avoid the temptation to relinquish his quest and later declares that “Ahab is forever Ahab”–he is forever the monomaniac bent on revenge (572). While Melville’s narrative works to paint a man of great complexity, Ahab must ultimately reject these layers and adopt a one-dimensional figure of himself in order to accomplish his task.

<15> Perhaps part of the explanation for the power and persistence of the Ahab trope arises from Ahab’s inability to rise above his need for revenge, even as he realizes its potential cost to his ship and crew. For three consecutive days, he calls for the lowering of the whale boats in pursuit of Moby Dick, and the whale’s fierceness and destructive nature seem only to spur on Ahab and his men. After the whale breaks two boats to splinters and scatters the crew’s harpoons across the sea, the crew returns to the Pequod to make repairs and resume the chase. Seeing the mechanical way in which his men shake off danger and hastily prepare to reengage Moby Dick, Ahab nearly falters: “As he saw all this; as he heard the hammers in the broken boats; far other hammers seemed driving a nail into his heart. But he rallied” (580). For one instant, the sight of his men’s blind allegiance horrifies Ahab, and he seems to recognize his own part in leading them to an almost certain death. This feeling, too, he is able to push through. As most know, Ahab and the men of the Pequod, save our narrator Ishmael, do not survive the hunt. Such an ending reinforces the powerful grip that obsession and revenge maintains on Ahab, despite his moments of sadness, regret, and longing for the comforts of home. The infamous ending of the novel lays the groundwork for adaptations to emphasize the moral of the story in regards to the hazards of pursuing vengeance, and this focus in filmic representations of Ahab is certainly not unwarranted. The risk, though, of recreating only this aspect of Ahab is that his narrative becomes an allegory for whatever might be convenient to the adaptor—a comment on the Cold War or a meditation on the War on Terror—and, as such, loses the nuance and complexity of Melville’s character study of a man grappling with the meaning of his own painful human existence.

<16> One example of an adaptation that becomes what Hutcheon might term a copy rather than a successful re-envisioning is John Huston’s 1956 film. Hutcheon and other media adaptation theorists often use the language of biological adaptation, which takes as a truism that organisms which fail to adapt to a new environment often fail to survive; similarly, texts that are placed into a new media format often suffer from an overreliance on fidelity to the written text. As Julia Sanders highlights, “Adaptation can be a transpositional practice, casting a specific genre into another generic mode . . . yet it can also be an amplificatory procedure engaged in addition, expansion, accretion, and interpolation” (qtd. in Fischlin 8). Huston’s film does little more than change genres from written to filmed text; it neither adds to nor complicates our understanding of Melville’s characters and themes, and therefore provides only a pale imitation of the novel. However, its moments of emphasis, placed alongside the Star Trek films discussed later, help us understand the continued presence of the Ahab trope.

“A Salty, Wet Western”: The Ahab Trope and John Huston’s Moby-Dick

“Each age will find its own symbols in Moby-Dick.” –Lewis Mumford

<17> The publication in 1941 of F.O. Matthiessen’s seminal work, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman, ushered in an era of reading Moby-Dick through the lens of the Cold War. During this time of national crisis, scholars turned to Melville’s novel as a means for making sense of an increasingly complex world. In such readings, Ishmael represents America’s freedom, while Ahab stands as the totalitarian dictator working in opposition to him. Moby-Dick becomes simply a battle between good and evil. It is from this angle that scholars read John Huston’s 1956 film adaptation, Moby-Dick. In “The Whale and the Minnow: Moby-Dick and the Movies” (1956), Milton Stern laments that the demands of the Hollywood adventure film turn Melville’s novel into “a salty, wet western” at the expense of “thematic profundity and unity” (472). He cites Huston’s Ahab and white whale as the “best examples” of this loss (472). Stern nevertheless praises the film for bringing Moby-Dick to the masses: “it is important that a profound document like Moby-Dick be taken from the relative inaccessibility of the classroom and be placed before millions in an exciting and popular mass medium” (471). Nearly 50 years later, Walter C. Metz responded to one critic’s claim that there is “widespread agreement” among Melville scholars that Huston’s adaptation is “unsatisfying,” arguing that “the elitist assumptions imbedded in such a knee-jerk critical assault on Hollywood films need to be challenged” (222). These responses may also be understood as symptomatic of a high/low culture tension: as Hutcheon points out, “So often film’s relation to literature has been characterized as a tampering, a deformation, a desecration, an infidelity, a betrayal, a perversion. The deeply moralistic rhetoric of such characterizations belies the fact that what is at stake here is really a question of cultural capital” (“On the Art” 109). Our aim here is not to join the “widespread agreement” about the film’s merit, or lack thereof, but to explore the ways and reasons Melville’s Ahab takes on a life of his own in filmic representations of this iconic character. Because Huston’s film was so influential in bringing Moby-Dick into the realm of popular culture, we begin our examination here as a means for understanding Ahab’s trajectory from Melville’s novel to the filmic adaptations and reinterpretations that he inspires.

<18> The Ahab of Huston’s film is immediately and irrevocably associated with his missing leg, entering less than six minutes into the film and signaling the film’s focus on one important aspect of the Ahab trope. As Ishmael fraternizes with the whalers at The Spouter Inn, we hear a clicking noise that will come to signify Ahab throughout the film: the measured sound of his ivory leg striking the pavement. The camera cuts from Stubb and Ishmael to a shot from between the windowpanes as a flash of lightning reveals Ahab, his back to the inn, walking the streets in his rhythmic march as an ominous thunderclap halts the whalers’ singing. The men become dejected and stare at their boots while Ishmael, shown in profile, gazes out after the Captain. He asks, “Who’s Ahab?”, to which Stubb replies, “Ahab’s Ahab.” It is a fitting reply that underscores the power of the novel as palimpsest. He needs no further description, as Ahab comes loaded with cultural meaning: everyone knows Ahab.

<19> Ahab’s less nuanced role as the tyrant dictator of the ship is reinforced when Ishmael hesitates to sign onto the Pequod, recalling that the biblical Ahab was purportedly a “wicked king.” Once the ship is under way, a shot of Ahab’s cabin underscores this impression, as Ishmael explains in voiceover that their “supreme lord and dictator” remains locked away during the daylight hours. The shot dissolves into a night scene of water lapping against the sides of the ship as the sailors sleep in the forecastle. Sounds of the sea gently rocking the creaking ship blend with a soft and sweet lull of violins. Ahab’s pacing thump of whalebone on wood turns the scene, and the strings take on a deeper, moody tone. The noise disturbs Ishmael’s sleep, and he comments on the strangeness of Ahab’s nightly habit. Instead of the rare event that we see in the novel, here, we learn that Ahab paces the deck “every night, all alone.” Image, dialogue, and sound work together to direct viewers and ensure they share Ishmael’s misgivings about Ahab and his motives. His behavior does not align with the norms of his profession, and it should strike us as unnerving. This, in turn, prepares us to be awed in his presence when we meet him in the next scene.

<20> Huston’s Quarter-Deck compresses several chapters in the novel and serves both as the crew’s introduction to Ahab and the announcement of his quest. Given the time constraints of a film, Huston and screenwriter Ray Bradbury perhaps do not have the luxury of prolonging the big reveal. As a result, we learn of Ahab’s plan to hunt Moby Dick within seconds of meeting him, which, in turn, boils his character down to the captain obsessed with enacting revenge on his foe. As the men scrub the deck of the Pequod, Ahab enters the frame and their work comes to a halt. In voiceover, Ishmael describes the captain as looming over them, and the camera’s low angle serves to reinforce this visually, as it will throughout the course of the film. Giving us first a brief glance at Ahab’s full figure, the camera cuts to a tight close up of his ivory leg, where it lingers as we hear Ishmael’s voice describe how Ahab’s “whole high, broad form weighed down upon a barbaric white leg.” This is a striking contrast to Melville’s Ishmael, whose eye is drawn first to the impressive physical presence of his captain, and for whom the leg is only an afterthought. Cutting back to Ahab’s face, the film presents the blank stare that comes to define Gregory Peck’s Ahab, connoting his single-minded purpose. The scene includes trademark moments from the novel, with Ahab vowing to chase the white whale across the globe, pouring grog for the crew, and inspiring their allegiance as they chant “death to Moby Dick!” With its steadily intensifying score, the scene captures the frenzy of its prose counterpart. In circumscribing Ahab in this manner, using his hunt to encompass his entire being, the film forecloses any possible depth in his character. The dead stare, mechanical voice, and ivory leg serve as the only elements of characterization necessary to tell this Ahab’s story.

<21> Huston’s film trains its focus on scenes that emphasize Ahab’s obsession with his quest for revenge. We see the captain baptize his harpoon in blood and squelch the St. Elmo’s fire glowing from his lance, a startling white shock of hair wildly marking his scar and a fierce defiance in his cold stare. The film also adds scenes in order to heighten this characterization. For example, when he learns from a passing ship that the Pequod is right on Moby Dick’s tail, Ahab orders his men to cut loose the whales they have killed so that he loses no time in pursuit of the white whale. Melville’s Ahab is careful not to make such a blunder. In order to ensure the loyalty of his crew, Melville’s Ahab understands that he must allow them the means of earning a living; Huston’s Ahab lacks such considerations and foresight. Notably, the film inverts a scene from the novel to illustrate these consequences. While in the novel Ahab meditates on the grounds he has given the crew to usurp his power, in the film it is Starbuck who voices these exact words as he tries to rally the mates to unite them against the raging captain.

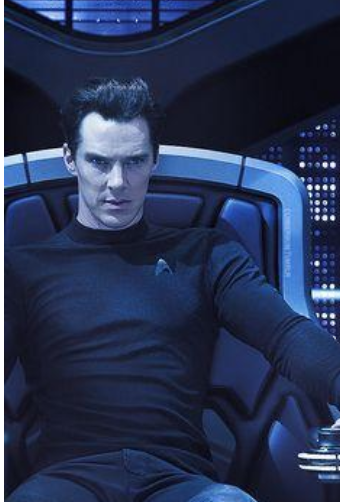

<22> Huston’s film does not neglect “The Symphony” scene, which is crucial to displaying Ahab’s “humanities,” but it, too, is slanted in a way that undercuts the vulnerable Ahab. We see no tear, and Peck’s mechanical delivery of the monologue serves to reinforce Ahab as resigned and unmovable. Whereas the novel situates family ties as central to Starbuck’s argument for ceasing the hunt, Huston’s film foregoes any mention of the men’s families altogether. The scene opens with Ahab on the ship’s prow, taking in “a mild, mild day…a mild sky” as soft violins instill a peaceful atmosphere. Ahab has the trace of a smile on his face as he takes in the blue skies, but this quickly fades, along with the violins, as he notes, “on such a day [he] struck [his] first whale, a boy harpooneer.” Like the novel, this monologue underscores the brutality of the whaling industry, illustrating how “forty years and a thousand lowerings” will damage the humanity and compassion of anyone. The repetition of “forty, forty, aye, forty years” further emphasizes the dehumanizing power of spending such a span of time employed in such “madness of the chase, this boiling blood and smoking brow.” While this brief interlude does add some nuance to Huston’s Ahab, it is fleeting at best. Ahab asks Starbuck to “stand close” so that he can “look into a human eye,” but instead of experiencing a moment of shared concern for and love of family, the scene swiftly shifts into the “Is Ahab, Ahab?” monologue in which the captain questions his own human agency. This move, in turn, works to position Ahab as a puppet of the fates who has nothing to lose and no human ties to pull him in the opposite direction.

<23> The circumstances and powerful imagery of Ahab’s death are the most prominent legacies of Huston’s film adaptation, and they are the core fragment that gets passed down through the popular culture references that follow. Huston’s iconic ending has all the fury and allegiance to vengeance that we see in Melville’s closing chapters, even if many of his narrative choices are pure invention. Most notable is Ahab’s death. His departure is so subtle in the book that it is easy to miss it entirely. Ahab’s final, and often parodied, vow marks his last act of darting the harpoon at his foe: “‘Towards thee I roll, thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee; for hate’s sake I spit my last breath at thee’” (Melville 583). He throws the harpoon but part of the line catches him “round the neck, and voicelessly as Turkish mutes bowstring their victim, he was shot out of the boat, ere the crew knew he was gone” (584). With its use of words such as “voicelessly” and “mutes,” the text goes to great length to emphasize the silence of this moment. Ahab disappears beneath the waves all but unnoticed by his crew. This is not the stuff of the Hollywood adventure film, though, and we might forgive Huston’s aesthetic choice as a practical one.

<24> What we cannot ignore, though, is that it is Huston’s Ahab, not Melville’s, who has entered the popular consciousness. Whether it is the film adaptations that follow, or the various other pop culture references, we see Ahab’s demise as Huston represents it: Ahab climbing onto the whale’s back, stabbing him with a lance, and, entangled in the lines wrapped around Moby Dick, drowning as a result. His dead arm moves in an arc as the whale swims away, beckoning the crew to follow. It is this image that becomes the Ahab of cultural knowledge, supplanting the textual Ahab and reducing him to the crazed, one-legged captain who is both literally and figuratively tied to the white whale. Even when other versions use Melville’s text in other ways, such as Khan’s paraphrasing discussed below, the death of Ahab is congruent with Huston’s character instead of Melville’s, pointing to the power of the film versions in shaping current cultural notions of the character and the messages he is deployed to communicate. We may attribute this in part to the expectations consumers bring to different generic forms. While a nineteenth-century romantic novel might dispatch of its central character more subtly, the mainstream Hollywood adventure film typically treats such a demise as a climactic moment; viewers have followed Ahab on this quest and expect to see him go down in spectacular fashion, fighting to accomplish a sense of justice.

“Wagon Train to the Stars” Star Trek’s Politics and the Ahab Trope

“For a Khan of the plank, and a king of the sea, and a great lord of Leviathans was Ahab.” – Moby-Dick, “The Pipe”

<25> Despite its short duration and low ratings as a television series in the 1960s, the Star Trek franchise, brought back for a third broadcast season due to one of Hollywood’s earliest letter-writing campaign by viewers, has had a lasting cultural impact in the United States. The original series spawned four additional television series that aired from 1987 through 2005 (with a new show reportedly planned for 2017), 13 films, an animated series, many best-selling books, and almost unlimited merchandise. Phrases from the show (“Beam me up, Scotty!”; “Space: the final frontier”) are familiar even among those who do not count themselves fans, NASA named a space shuttle Enterprise (sadly, NASA’s spaceship was too heavy for actual flight), the show’s technology has prefigured or even inspired inventions commonly used today, including the cell phone, and physicists such as Michio Kaku and Lawrence M. Krauss have used the show to explain scientific concepts to non-scientists. The show is still recognized for having depicted Hollywood’s first televised interracial kiss (between Kirk and Uhura in “Plato’s Stepchildren”), and although the original Star Trek’s female characters were far from feminist icons in their scanty uniforms, the sheer presence of women and men serving together, and Uhura’s character herself, inspired many viewers. Many scholars have also studied the show’s impact from multiple disciplinary perspectives: Nicholas Sarantakes highlights several of the most common scholarly approaches to the original series, including analyses of the ways it portrays gender and race, its philosophical and religious ramifications, and its reliance upon common western structures of myth and folklore. However, Sarantakes also argues “that the makers of the original Star Trek series wanted the United States to play a constructive role on the world scene and . . . used the television show to critique U.S. foreign policy” (74). Although Sarantakes deliberately restricts his argument to the original television series, other scholars have made similar claims for the movies and later shows in the franchise. Diana Relke, for instance, analyzes the “rational secular humanism celebrated by Star Trek” in a post 9/11 context and cites other scholars who have debated the ways in which the franchise reinforces an “American imperialist mindset” (xi), but she finds also that it “often manages . . . to offer up fragments of remarkably progressive insight” (xx).

<26> As science fiction, the original Star Trek was well-positioned to function as allegory without generating criticism for the most part. Sarantakes quotes a producer of the television show explaining that:

Working in the science fiction genre gave us free rein to touch on any number of stories. We could do our anti-Vietnam stories, our civil rights stories . . .Set the story in outer space, in the future, and all of a sudden you can get away with just about anything, because you’re protected by the argument that ‘Hey, we’re not talking about the problems of today, we’re dealing with a mythical time and place in the future.’ We were lying of course, but that’s how we got the show by those network types. (Lucas qtd. in Sarantakes 79)

<27> The show, which Roddenberry famously pitched as “Wagon Train to the Stars,” was lauded by many viewers as a celebration of humanist values; indeed, Roddenberry envisioned a future in which “enlightenment is achieved by the 23rd century, freeing humanity to travel the universe,” and Captain Kirk is intended to be a figure of “compassion and empathy for others” (Short 183). Star Trek engaged with weighty questions of imperialism and culture that reflected the desire of its producers to function as sociopolitical critique, and, as Geraghty points out, “Kirk would substantiate his desire to do good by defending his actions in the name of freedom for those people he thought were being oppressed” (58), even when he blatantly disregarded Starfleet regulations (and Spock’s advice) about not interfering with the development of other species. Captain Picard in the Next Generation spinoff series is even more explicitly a figure of rational humanism, which makes these captains’ occasional lapses into less-enlightened emotional territories all the more disturbing for their crews – and for viewers. One recurring theme in the Star Trek franchise centers upon the dangers of obsession and revenge, an argument that is often conveyed by evoking Melville’s Moby-Dick and the iconic figure of Captain Ahab. As we have already seen, the Ahab trope pervades all kinds of popular culture, and we can trace its influence throughout the Star Trek franchise, from storylines in the first series to sets and literary references in the Next Generation show, to several of the movies. In the original series, three shows clearly drew upon Melville’s book in order to argue the negative costs of revenge; we will briefly note these here (non-chronologically) to illustrate the degree to which the novel’s themes and characters inform the franchise, before more closely analyzing how the Ahab trope operates in the films.

<28> Two episodes of the second season of the original series serve as rather heavy-handed allegories for the arms race and the consequences of a leader who is obsessed with revenge to the detriment of his ship, his crew, and himself. In “The Doomsday Machine” (October 1967), Captain Decker of the USS Constellation is obsessed with destroying a device responsible for killing his entire crew. Decker embodies the Ahab trope, seizing command of the Enterprise while Kirk is away, pulling rank on Spock, and ignoring Spock’s advice not to pursue the machine because it will destroy the Enterprise. The danger of obsession, especially when weapons of mass destruction are available, is clearly a moral lesson conveyed in this episode. Later in the second season, the episode “Obsession” (December 1967) shows Kirk temporarily fixated on gaining revenge on a gas creature who had killed the commander and half the crew of a ship on which he had served as a young officer. Kirk’s obsession with revenge, to the extent that he puts his crew and ship in danger, not to mention a whole planet of people in need of the Enterprise’s cargo of medicine, clearly evokes Ahab’s mad pursuit of the white whale. In both cases, however, it is not just the fact that revenge is an emotion that so-called enlightened individuals and societies should have renounced that lends metaphorical power to the Ahab trope; it is the actual power of the captain who falls prey to obsession that makes it such a strong cautionary example. The commander of a Federation Starship is a representative of law and order, and by extension the body politic, in a society in which individuals have relinquished the rights and responsibilities of policing and punishment in favor of the State. If he loses control of his instinctive responses, he endangers not just himself, but the entire community of people over whom he exercises power.

<29> The episode that introduces the character who most clearly illustrates the franchise’s dependence on the theme of revenge is the first-season episode “Space Seed,” which aired in February, 1967. In this episode, the Enterprise encounters the derelict ship Botany Bay from the late 20th century, with its cargo of cryogenically-frozen bodies. After they revive Khan Noonien Singh, the leader of a group of genetically-enhanced “superhumans” who had considered their superior intellect and physical prowess justification for ruling on earth, Spock explains that Khan and his 72 surviving followers escaped the Eugenics Wars they had instigated on earth. Khan formulates a plan to commandeer the ship and attempt to seize power in the 23rd century. Kirk prevails, of course, but also subjects Khan to a trial on ship and subsequent marooning on an uninhabited planet, Ceti Alpha 5. Although there is no overt Melvillian imagery in this show, it sets the stage for one of the franchise’s most popular films, 1982’s Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, remade in 2013 as the second film in the franchise’s theatrical reboot, Star Trek Into Darkness.

<30> One of the most popular movies in the franchise, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan pits Kirk against Khan in a story of revenge that also focuses on the costs of growing older and accepting the hard lessons of maturity. The original crew no longer roams the galaxy; instead, they occupy positions of authority in Starfleet, and Kirk’s birthday is a plot device that introduces the first of two strong literary references in the film, when Spock presents him with an antique copy of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, and McCoy gives him a pair of glasses with which to read the book. When an initially-routine training flight turns into an actual mission, Kirk comes face to face with his estranged son and battles a vengeful Khan, who has again been accidentally rescued, this time by a ship on which Chekov serves. Taking up where Space Seed left off, Khan seeks revenge on Kirk not just for stranding him and his crew on a planet that had lost its ability to sustain life because of a shift in its orbit, but also because Khan’s “beloved wife” had died there. Dickens’s novel is clearly intended to evoke themes of friendship and unselfish sacrifice among Kirk, Spock, and the world of Starfleet, just as Ishmael and Queequeg’s friendship does in Melville’s novel. Kirk reads the opening lines of Dickens’s book at the beginning of the film (“It was the best of times, and the worst of times”) (3), indicating his reflective mood as he ponders his advancing age, while his voiceover paraphrase of its closing lines at the end of the film (“It is a far, far better thing I do than I have ever done before. . . a far better resting place I go to than I have ever known”) accompanies a shot of Spock’s coffin on the newly-established Genesis planet and establishes Spock’s sacrifice for the crew; this echoes the ending of Melville’s novel, with Ishmael’s description of Queequeg’s “coffin life-buoy [that] shot lengthwise from the sea” (586) to save his life.

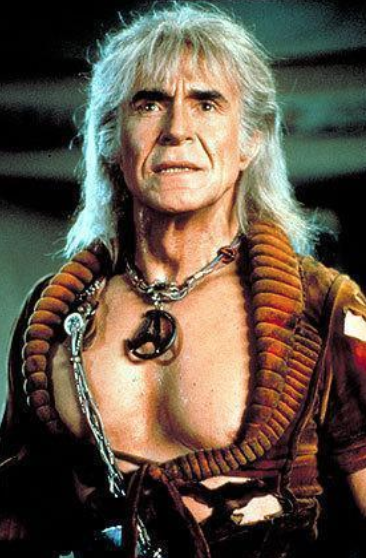

<31> Where themes from Dickens are deployed to characterize the crew of the Enterprise, Khan unequivocally exemplifies the Ahab trope from his first appearance in the film. Just as Melville’s Ahab enters the story after the other characters are established, Khan shows up as the film’s source of external conflict to help Kirk resolve his angst over aging and learn to handle loss. When Chekov and his commander discover the cargo pod in which Khan and his crew have been living on Ceti Alpha 5, the camera pans over the bookcase and lingers on his battered copy of Moby-Dick, relying no doubt on the same kind of cultural knowledge that Huston’s movie deploys when Stubb says to Ishmael, “Ahab’s Ahab.” The camera’s long focus on the novel immediately draws the audience into the world of the Ahab trope, indicating that The Wrath of Khan will re-inscribe the character of the obsessed captain; however, this does not occur in the newer film, despite the use of Khan as villain.

<32> When the franchise “rebooted” the original characters in 2009 with J.J. Abrams’s Star Trek, the plot included an alternate timeline that allowed the young Kirk, Spock, et al. to draw from the established characterizations, but also have new relationships (such as Spock and Uhura’s romance) and new adventures. Critics and commentators generally refer to the original timeline and characters as “Prime” and the alternate reality characters and time line as “Alternate,” a convention we will continue in this article. 2013’s Star Trek Into Darkness recycles the character of Khan as the villain, but very little except his name and the number of his followers remain from either “Space Seed” or Wrath of Khan. His origin story and motivations differ significantly in this alternate history, and neither Kirk nor Khan quote from famous novels (indeed, there are neither bookshelves nor reading glasses in this film). Although Into Darkness retains the focus on friendship, it is the developing relationships of the young characters on display, and the movie has a very different feel from its 1982 predecessor.

<33> The Khan of Into Darkness is motivated to seek revenge for specific and immediate reasons, although he is at first seen as a mystery figure who convinces an anonymous Starfleet officer to help him carry out an attack on Starfleet. His identity as the terrorist known as “Harrison” is more firmly established after he attacks Starfleet command, and we later learn that he has been weaponized and radicalized, which positions the film as allegory for the War on Terror. As a result of this attack, Starfleet’s commander, Admiral Marcus, sends Kirk, Spock, and the Enterprise on a mission to assassinate Harrison, with 72 mysterious torpedoes on board the Enterprise. The fugitive is hiding on the home planet of the Klingons, a species recently discovered and considered an existential threat by Marcus. After a brief struggle with a strong urge to carry out Marcus’s orders as an act of vengeance, Kirk is eventually persuaded by Spock to follow an ethical and lawful course of action: he decides to defy orders and capture the fugitive instead, so he can return to earth to face trial. Harrison surrenders to Kirk, and leads him to investigate the torpedoes on the ship and learn that they contain the 300-year-old cryogenically frozen bodies of Harrison’s crew. Harrison reveals his true identity as Khan and explains that his ship had been discovered by Admiral Marcus, who used Khan’s superior intellect and savage nature to design weapons and strategies to use against an “uncivilized” foe – presumably the Klingon Empire. Khan is thus at first revealed in a somewhat sympathetic light, especially as Admiral Marcus shows up in the aptly (if somewhat too-obviously) named U.S.S. Vengeance, intent on destroying the Enterprise and its crew and painting Kirk as a renegade who started a war with the Klingons. Although Kirk and Khan temporarily join forces to destroy Marcus, and Khan alludes to his care for his cryogenically frozen crew, Khan’s villainous nature is revealed as he betrays Kirk, and we learn that Spock Prime characterized Khan as “the most dangerous adversary the Enterprise ever faced” in light of his desire for “the mass genocide of any being [he finds] to be less than superior.” Of course, Kirk and Spock prevail over Khan, but the differences between films, as well as a consideration of the Khan character throughout the franchise, show how the use of the Ahab trope persists throughout these stories as a warning of the dangers of obsession and a focus on attaining revenge instead of pursuing justice grounded within an ethos of compassion, enlightenment, and liberal humanism.

<34> Although the Ahab trope represents obsession in popular culture, including the Star Trek franchise, he has a corporeality and a spiritual dimension in Moby-Dick that is somewhat revived in these films, one way that they approach a complexity beyond the trope. As we argue earlier, Melville’s character is often reduced down in later representations to his physical disability – his peg leg – which serves to overshadow his strength and sheer physical presence. This powerful Ahab is a crucial aspect of Khan in all his Star Trek manifestations, and in fact, his strength serves to frame these adaptations of Melville’s novel in the context of contemporary fears about the possibilities and limitations of medical technologies in defining humanity. Hutcheon emphasizes that adaptors often make changes “in an attempt to find contemporary resonance for their audiences” (142), and Khan is the very opposite of the “crippled” Ahab in his genetically-enhanced physical strength and intellectual prowess, a fact that he and the other characters repeatedly emphasize, from the moment he wakes up on the Enterprise in “Space Seed” and threatens Dr. McCoy with a scalpel. In the first show, Khan and Kirk have the inevitable fist fight, during which Khan reminds Kirk that he has “five times” Kirk’s strength, but the captain knocks him out using a club. Meanwhile, Spock warns that “superior ability breeds superior ambition,” a reminder that Khan’s myriad strengths are accompanied by a dangerous ethos. In The Wrath of Khan, his physicality and presence are evident from his first appearance in the abandoned cargo pod, as he enters in from the blowing sand and removes his o uter garments, revealing a fierce gaze and muscled physique. He lifts the hapless Chekov off the ground with one hand, and explains that only his “genetically engineered intellect” had allowed him and his crew to survive the harsh environment. As he challenges Kirk from the bridge of their commandeered starship, Khan’s second in command, Joachim, suggests that they take the ship and conquer the universe instead of obsessing over Kirk because, he urges, “you have proved your superior intellect and defeated the plans of Admiral Kirk. You do not need to defeat him again.” The rebooted Khan in Into Darkness is so powerful that he is able to, in Kirk’s words, “[take] out a squad of Klingons singlehandedly” and McCoy remarks that they apparently “have a superman onboard.” McCoy takes a sample of their prisoner’s blood, a seemingly inconsequential plot device that later has the most dramatic of consequences when it brings Kirk back to life. The Khan of Into Darkness is so powerful, in fact, that the only crewmember who has a chance of physically overcoming him is the half-Vulcan Spock, who has always been stronger than his full-human companions, and he only succeeds with Uhura’s assistance. As an Ahab adaptation, then, Khan recuperates Melville’s powerful Ahab in physical prowess, and escapes the Huston film’s reliance on the peg leg that “weighs” the filmic Ahab down, while at the same time reflecting fears surrounding the use of genetics to “enhance” humans; it is this quality of strength, and potential danger as a leader, that helps make Khan “a more complete Ahab” than most others in popular culture.

<35> A charismatic leader is compelling, but also potentially frightening when we consider the range of his power and influence, especially if he is also susceptible to an instinct like the desire for personal vengeance. Khan’s physical strength and intellect are accompanied by personal magnetism and a sweeping worldview, perhaps because Melville’s Ahab is both compelling and complex in his obsession. His quest to take revenge upon the whale envelops his crew in his tragic vendetta, but he also cares for their well-being, from his choice to refrain from pacing if it would disturb their rest to his realization of the importance of family ties. Both these nuances are lost in the Huston film, with its use of the clicking noise of his whalebone leg as a character motif and deletion of the men’s families entirely. This humanizing element of Ahab is lost in the Ahab trope, but the makers of The Wrath of Khan apparently decided that an egomaniacal superman also needs a softer side. In their first encounter, Khan informs Chekov’s Captain Terrell that his crew was “sworn to live and die at my command” 200 years earlier, highlighting their fanatical loyalty to him, and he explains that his deep hatred of Kirk can be attributed to the loss of his wife and crew members. Joachim is Khan’s devoted second-in-command, even daring to suggest that his leader abandon his quest for revenge, but ultimately acceding to Khan’s obsessive quest even at the cost of his own life in a clear parallel to the interactions between Ahab and Starbuck in Melville’s novel. Joachim’s death and last gasped assurance that Khan’s “is the superior intellect” provides Khan with yet another reason to desire Kirk’s destruction. But the rebooted Khan is very different, and consequently lacking in depth. In Into Darkness, we never see Khan with his crew. Granted, we hear him talking about how devoted he is to them, and referring to them as his family, but his character is less nuanced because we have no way to judge his level of care for them through an examination of their onscreen relationship. In this way, the earlier film presents a slightly more “complete” Ahab, whereas the Ahab trope of Into Darkness relies on a narrative that works to make the terrorist sympathetic – until his obsession becomes paramount and he betrays his temporary allies on the Enterprise.

<36> If we are to understand the appeal of a captain fixated on revenge to the extent that he loses his ship and the lives of his crew and himself, we must remind ourselves of Melville’s Ahab, who is obsessed not just with the whale as animal but as physical manifestation of the mystery of the universe. Melville’s Ahab is not just obsessed with revenge; he is also sorrowful and self-reflective, fully aware of the cost of his decades-long quest. Huston’s filmic portrayal evacuates Ahab of his humanity almost entirely, and the various iterations of Khan never reach the same level of complexity, although the Khan who returns in the first film is, like both Kirk and Melville’s Ahab, older and possessed of a lifetime of experiences upon which to reflect. He fixates on Kirk, embodying the Ahab trope with Kirk as his “whale” – made abundantly clear by his key paraphrases from the novel, first when he declares to Joachim, “He tasks me. He tasks me and I shall have him. I’ll chase him around the moons of Nibia and round the Antares maelstrom and round Perdition’s flames before I give him up.” The “him” here is of course Kirk; Khan has abandoned his dream to conquer the universe in favor of destroying Kirk. When he attacks the Enterprise in one of their final skirmishes, he tells Kirk over the intercom, “I mean to avenge myself upon you.” Joachim must force his captain to back off until they can make repairs, illustrating how Khan’s obsession has compromised his superior intellect and thereby his ability to command. Khan declares he wants to “keep on hurting” Kirk by stranding and burying him alive just as Kirk had “done to her,” presumably referring to his wife. This Khan, as reduced as he is from Melville’s Ahab, nonetheless represents a more faithful adaptation of the character than the one in the 2013 film. The most recent Khan’s need to save his frozen crew from the torpedoes in which they have been stored and held hostage by the fanatical Admiral Marcus is understandable; this plot twist perhaps represents the filmmakers’ desire to update this adaptation of Khan by turning him into a victim in a way that the earlier Khan iterations never were. However, once he and the crew of the Enterprise defeat Admiral Marcus, Khan betrays Kirk and Spock, becoming less sympathetic and losing even the relatability of Khan in the earlier film.

<37> Serving as an adaptation of an adaption, with a plot that borrows from “Space Seed’s” origin story and reverses the roles of Kirk and Spock from Wrath of Khan, Into Darkness manipulates the Ahab trope but keeps it focused on revenge by parceling out the role of Ahab to four characters: Harrison/Khan, Admiral Marcus, Kirk, and Spock. This strategy allows the film to explore the developing friendships of the Alternate timeline (in comparison to the established relationships in Wrath of Khan), but also positions it as clear allegory for the War on Terror, hearkening back to the intent of the first television series in the 1960s. Much of the film’s visceral action revolves around the characters seeking revenge, but there is almost no reflection on the stakes of such a quest. Khan is the film’s first Ahab, with a significantly-altered origin story in the 2013 film that renders it a clear critique of political vengeance: instead of being revived by the Enterprise crew and exiled because of his dangerous ambition, the newer film has him discovered by Admiral Marcus and radicalized as a direct result of Marcus’s use of his intellect and inherent savagery to create weapons. The most obvious Ahab trope in the film and perhaps the most overdone figure of obsession is Admiral Marcus. His preemptive vendetta against the Klingon Empire, which has not yet constituted a danger to Starfleet, causes him to betray all of Starfleet’s humanistic values. As allegory, it is hard to miss that the Klingons represent an existentially-dangerous Other, similar to the way the rhetoric of the U.S. War on Terror has framed the Middle East, its culture, and its inhabitants, but Marcus is the one in this universe who uses hostages, as a way to manipulate Khan into helping him prepare for war. For the film’s third Ahab, we return to the temporarily-obsessed Kirk of the earlier television shows, who at first wishes to obey Marcus and assassinate Harrison in revenge for the death of Starfleet leadership (including Kirk’s mentor, Christopher Pike), despite knowing that Starfleet’s philosophy, as Roddenberry had envisioned, is too enlightened and progressive to engage in such morally-detestable tactics. Like Kirk Prime, however, he eventually heeds his first officer’s advice and decides that Harrison should return to Earth and stand trial for his crimes.

<38> Perhaps the most shocking figure to embrace the Ahab as messianic leader trope in the 2013 film is Spock. His transformation arises from changes in the characters’ lives in the Alternate timeline that lead to a more emotional Spock, as well as the film’s radical role reversals in the climactic scenes endangering the ship and crew.. In The Wrath of Khan, Spock exposes himself to radiation to repair the Enterprise’s warp core, and his death carries great emotional intensity for characters and audiences alike. The full effect of Spock Prime’s self-sacrifice for the greater good is seen in two scenes. The first occurs when Kirk is seen reading the end of A Tale of Two Cities, in which Sydney Carton willingly goes to the guillotine instead of Charles Darnay, declaring, “I see the lives for which I lay down my life, peaceful, useful, prosperous and happy, in that England which I shall see no more” (469-70), and he acknowledges his son’s assertion that Kirk had never faced death in all his years as a Starfleet officer. The second scene is the ending, with Kirk’s voiceover quoting the last lines of Dickens’s book in referring to Spock’s actions. In the 2013 film, role reversals position Kirk as the one who dies from repairing the warp core. A vengeful Alternate Spock acts very differently from the older Kirk in the 1982 film. Despite his half-Vulcan heritage, Alternate Spock seems obsessed for a few moments, pursuing Khan to Earth, where they engage in a brutal and precarious fistfight atop vehicles flying above San Francisco. He seeks to avenge Kirk’s death with an emotional intensity that Spock Prime would never have revealed, and only stops trying to kill him when Uhura tells him keeping Khan alive is their only chance to save Kirk. This radical change in Into Darkness from its 1982 source text is similar to the changes made in Huston’s film from Melville’s novel, where Starbuck, after Ahab’s death, becomes enraged and tells the crew to kill Moby Dick (despite Stubb’s suggestion that they go back to the ship and leave him alone.) This is totally out of character for Melville’s Starbuck, just as Alternate Spock’s short-lived quest for revenge is out of character for Spock Prime. Khan’s superhuman blood revives the recently-dead Kirk, and Into Darkness ends with a voiceover montage showing Khan back in cryogenic freeze with his crew and a memorial service at which Kirk pays lip service to the notion of revenge as a destructive emotion, and a final scene in which the Enterprise crew is reunited onboard ship as they begin their “five year mission.” Unlike the end of the 1982 film, which highlights the costs of revenge to the individuals and the community in a manner reminiscent of Melville’s Ahab and Ishmael, the 2013 film contains no significant examination of the true cost of revenge. None of the Ahab figures are especially reflective about their choices to pursue vengeance, and no one really loses anything, despite Kirk’s memorial service speech: no sacrifice has been made, since Kirk has come back to life, and the crew is rewarded with the Enterprise and the prospect of a “five year mission” gallivanting around the galaxy. In their obsessive quests, all four characters illustrate the power of the Ahab trope, but none approaches the thoughtfulness of The Wrath of Khan as an adaptation, let alone the complexity and depth of Melville’s Ahab.

Conclusion: A More Complete Ahab

“Ah, Kirk, my old friend, do you know the Klingon proverb that tells us revenge is a dish that is best served cold? It is very cold in space.” Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan

<39> For Star Trek fans, Khan is an enduring favorite, which may explain why this character was chosen as the villain in the 2013 reboot. He is both fascinating and frightening, with his artificially-enhanced intelligence and physicality, his fanatically-devoted crew, and his desire to destroy the man who hurt him on a personal level (Kirk in the earlier film for his beloved wife’s death in exile on Ceti Alpha 5 and Marcus in the reboot for holding his frozen crew hostage), as well as thwarting his grand ambition. But his quest for revenge in The Wrath of Khan is for most viewers only relatable until it veers into obsession and destroys his ship and crew. Like Melville’s Ahab, his humanity, expressed in his attachment to home and family and consideration of his crew, lifts him above mere caricature. Linda Hutcheon highlights the ways that adaptations can successfully transcend mere copies of their source texts, asserting that “When we adapt, we create using all the tools that creators have always used: we actualize or concretize ideas; we simplify but we also amplify and extrapolate; we make analogies; we critique or show our respect” (“On The Art” 109-110). This reminder that adaptations hold traces of past stories, while simultaneously asking us to tell new stories about our own time and place, leads to a question of why certain canonical novels merit repeated engagement and involvement: what do they offer new audiences over the centuries, and how are their themes and characters translated for new environments? Melville’s Moby-Dick is over 150 years old, hundreds of pages long, and full of dense descriptive and explanatory passages, narrative asides, and intertextual references; it was a commercial failure during Melville’s life, being rediscovered and hailed as an American classic only in the 20th century. Despite its literal and metaphorical heft, the novel and its characters, especially its obsessed captain, continue to resonate with readers. Even more significantly to our argument, it has taken on a life of its own, escaping its high culture niche and influencing popular culture in countless ways, many astonishing in their illustration of how the whale and the crew of the Pequod have become part of our current vernacular environment. For the most part, cultural references to the novel are a mere echo of Melville’s powerful vision: the whale remains a formidable beast, but Captain Ahab’s sorrowful self-knowledge, his physical presence, and his charisma are generally reduced to a caricature stumping maniacally around the quarterdeck and screaming for blood. Nonetheless, this shadow of Melville’s captain has gained a life of his own, becoming the “Ahab trope” that draws upon cultural knowledge of the basic outlines of the character, representing a continuing fascination with the place of revenge in our individual lives and social relationships, as well as with our public and political selves.

<40> Philosophers as far back as Aristotle have struggled to define the impulse to vengeance, to distinguish revenge from justice, and to suggest a way for the state to regulate this most primal of human emotions, while the enduring relevance of revenge as a theme is evidenced in the vast body of literature that takes this topic as a focus. This makes sense if we accept that the urge to return injury with reciprocal injury has its roots in our biology and evolution, but we also like to think that we have advanced as a species beyond our instincts. Law professor Thane Rosenbaum argues, “Despite the stigma of vengeance, it is as natural to the human species as love and sex. In art and culture, everyone roots for the avenger, and audiences will settle for nothing less than a proper payback,” and nowhere is this more true than in the continuing life of the Ahab trope – a “fragment,” to return to Denis Donoghue’s term, but one that illustrates our continuing fascination with the process of revenge. Examining how it operates in the Star Trek universe is illustrative of how Melville’s character has been absorbed into popular culture to the extent that we can easily identify a post-human egomaniac as a version of Ahab because they share a basic human desire for “payback,” in Rosenbaum’s word. The character of Khan serves as a touchstone, not just because of his longevity throughout the franchise, but also because he has explicitly been cast each time as the obsessive captain-figure, allowing us to analyze how well the television episode and two films in which he appears deploy the message of the Ahab trope and attempt to serve as adaptations of Melville’s novel.

<41> As Rosenbaum points out, audiences frequently love to see “payback” in film – there is a distinct satisfaction in seeing a character with whom we empathize achieve vengeance for some unjust insult or injury. It is no coincidence, however, that Rosenbaum qualifies the word “payback” with the descriptor “proper.” We need to agree that the injury is sufficient to warrant a retributive response, and to feel that the response is proportional to the injury. The Ahab trope taps into our desire for justice, but only when we understand and sympathize with the victimized figure. When the obsessive captain goes too far, or when we do not have enough information about the motivation for his vendetta, we cannot enter wholeheartedly into his quest for revenge. Even more significantly to the Star Trek franchise, the story of a powerful man in the grip of a primitive instinct offers a cautionary tale. As members of a society that has generally agreed that the personal impulse to inflict revenge is detrimental to the social contract, we have transferred the power for punishment to the government, and remain wary, for the most part, of vigilantism. Philosophers such as John Locke, for instance, argue that political entities possess “a Right of making Laws with Penalties of Death, and consequently all less Penalties” (Two Treatises 2.3), and this is still one of the primary functions of the state. Starfleet officers such as Kirk, Spock, Commander Decker in “Obsession” and Commander Marcus in Into Darkness all represent a supposedly enlightened, humanist government; when they fall prey to their primal instincts, their actions will inevitably affect their crew, any civilians in the way, and in some cases, whole planets and planetary systems. Khan is even worse, for he acts within his own morality, disdaining any legal or other restrictions on his path to achieving revenge. The Ahab trope in a Tom and Jerry cartoon is amusing, but a film that places that obsessive captain at the helm of a powerful weapon of mass destruction uses that trope to ask us to consider the potential catastrophe of such power in the hands of a leader who lacks respect for legal limitations or human values.

<42> Despite, or perhaps due to his quest for vengeance, much about Melville’s Ahab is sympathetic. He is not a young man; he has been roaming the seas chasing whales, and seeking to understand the mysteries of the universe, for 40 years. Like Ahab, Kirk in The Wrath of Khan is an older man reflecting upon his life, and Spock’s sacrifice forces him to finally mature by confronting mortality in his acceptance of Spock’s death. This film’s thematic emphasis on maturity, friendship, and loss moves it beyond a simple celebration of vengeance, suggesting that as an adaptation, it asks us to see it as a palimpsest and revisit the deeper meanings in Melville’s novel. Hutcheon asserts that “An adaptation is not vampiric: it does not draw the life-blood from its source and leave it dying or dead, nor is paler than the adapted work. It may, on the contrary, keep that prior work alive, giving it an afterlife it would never have had otherwise” (176). The characters in the Star Trek films may not be called Ahab or Ishmael (or Queequeg, for that matter), but these movies, not to mention the other many pop-culture references to the Ahab trope, render Melville’s novel still relevant, if not fully understood or appreciated. Weiner refers to Moby-Dick as a canonical work that “has crossed a border to forge a new frontier,” underscoring its continued powerful resonance. Adaptations of the novel such as Huston’s film faithfully recreate only the broad strokes of the story, and as simplistic imitations, leave viewers little opportunity to relate to the characters or reflect on the meaning of Ahab’s quest for revenge. While The Wrath of Khan explicitly evokes the novel, the struggles of its familiar characters as they grapple with aging and mortality framed by the costs of revenge engage us with some of the novel’s complexity but do not attempt to merely copy it; by contrast, Into Darkness co-opts the villain of its 1982 film predecessor but relies too heavily on the Ahab trope and obvious allegory instead of reflecting on the human cost of vengeance. Placing Melville’s canonical text in the Star Trek universe and dressing Ahab up as a futuristic terrorist or genetically modified supervillain certainly gives continuing life to an old text, but returning to Melville’s theme of revenge requires us to keep examining the power of this emotion in our lives, which continues to shape our characters and interactions with those around us.

Notes: