Winthrop and Watchmen: Liminality, Transformation, and American Identity

by Jennifer Heinert and Katie Kalish

<1> In his 1630 sermon, “A Model of Christian Charity,” John Winthrop writes to his peers journeying on the Arabella to the New World to propose how the tenets of their religion will help their community thrive. He begins by acknowledging the reality and divine nature of inequity and uses that foundation to connect to the ideals of justice and mercy, emphasizing the significance of the choices that the Christian individual makes as part of the larger one body in Christ (171). As a way to forestall conflict among his fellow colonists within their future community, Winthrop focuses on the ideals of togetherness and community as a means to avoid the potential pragmatic, moral, and religious failures of their endeavor. He devotes much of his sermon to defining those ideals for his particular Puritan-influenced version of Christianity. His “model” would greatly influence the many colonies, and eventual nation, that would grow from this community.

<2> The legacy of Winthrop’s colonial-cum-nationalistic narratives of “America” are engaged with and problematized by the graphic novel Watchmen, published in 1986. Writer Alan Moore and artist David Gibbon’s narrative begins over 250 years later on October 12, 1985–Columbus Day–or the day that has long-signified America’s cultural remembrance of its origins, celebrated first in the 18th century and becoming a federal holiday in 1937. The holiday itself continues to be representative of the turbulent histories of America, histories that have often privileged the white dominant culture and excluded many others. From the very first text, Moore and Gibbon’s work invokes the conflicting definitions of American identity and dwells in the complex liminal spaces of a fictional America. Each “superhero” of Watchmen embodies an identity that is what Homi Bhabha would call a “radical perversity” of Winthrop’s Puritan definitions of justice and mercy: Edward Blake (the Comedian) engages in the process of executing mercy and justice with no actual connection to those values, while Walter Kovacs (Rorschach) represents a “no mercy” individualism that both invokes a strong sense of justice while bordering on anarchy (Bhabha 303). Jonathan Osterman (Dr. Manhattan) is representative of the future and strongly detached from the community and its values, while Dan Drieberg (the second Nite Owl) demonstrates an ideal and romanticized notion of justice. Finally, Adrian Veidt (Ozymandias) is undoubtedly a murderer (when he attempts to unite the global community against a threat in order to prevent it from self-destruction); he defends his acts of terrorism as both merciful and just. These characters occupy the complex liminal spaces in many facets of their identity, from their unique roles as superheroes all the way to the “simpler” identity as American individuals who work within a community to promote justice and mercy.

<3> Using liminality as a framework for understanding these two disparate texts demonstrates the complexities of defining societal ideals and their implications for American identity that arise from competing ideologies. Winthrop’s text, which deals in absolute rules, attempts to forestall a new set of rules for engagement derived from people’s experience in the new world. In essence, Winthrop limits liminal complexity by using the Bible as an absolute standard for governing action. Moore and Gibbon’s text, however, both reflects the absolutes of Winthrop’s model and further complicates them. The conflicting definitions of American Identity in the value systems of each work demonstrate the puritanical influences on American identity, morality, and class systems. Both texts suggest an American ontology that prompts flawed individuals to strive for goodness–a persistent and problematic theme of American national mythology. This essay uses Victor Turner’s theories of liminality as well as Homi Bhabha’s The Location of Culture to explore the construction and evolution of American identity. Winthrop’s hopeful and didactic text prompts readers to cast the actions of the superheroes in Watchmen in a way that both questions and reinforces the Puritan ideals that underpin definitions of American identity. Both the 1630 Puritanical sermon and the post-nuclear collection of superhero narratives center on communities that face uncertainty and potential extinction. The ideals of mercy, justice, and the role of individual and community are central to the success of these both old and modern American societies, and yet their complexity leaves the reader contemplating the liminality that results from competing ideologies about how to uphold these American ideals.

<4> In many ways, the palimpsestic definition of American identity is an ideal exploration of liminality. Created from “in-between spaces” and multiple cultures and conceptual and organizational categories, it is by definition the “terrain” on which a nation that mythologizes selfhood and individual achievement within a context of a hegemonic dominant culture is constructed (Turner). It is primarily this narrative and value of individualism that creates the interstitial spaces that “initiate new signs of identity, and innovative sites of collaboration, and contestation, in the act of defining the idea of society itself” (Bhabha 2). Winthrop’s sermon is written both by and for liminal people–people at the “threshold” and “betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremon[y]” (Turner 95). His purpose is to establish structures to govern the members of this yet-to-be-established community. As the structures of the community-that-becomes-America change over time, readers can trace the evolution of new ideas, rejections and reshapings of those ideas, and their implications for American identity.

<5> Winthrop’s faith, contextual experiences, and vision for the new colony require him to expound upon both the individual’s personal responsibility and their obligations to their community, ruled absolutely by mercy and justice in a Christian universe. Centuries later, the world in Moore and Gibbon’s work shows how those narratives both represent individuality in many different ways, and how the ideals of mercy and justice are used to shape, destroy, rationalize, and defend the co-existing definitions of individuality and American identity. The “American” in Moore and Gibbon’s work is a crossroads of wide-reaching, incredibly diverse possibilities–taken collectively, the superheroes in Watchmen prompt the reader to define and question the categories and the values that define and are defined by the American community.

<6> John Winthrop’s unique rhetorical situation prompted him to clearly establish the ideals of justice and mercy in a way that supports the advancement of this new American community. In doing so, Winthrop is constructing a new “American Identity” of sorts; he is creating a set of guidelines for existing and thriving in a new, idealized, Puritan community and he calls on those traveling with him to the New World to embrace his ideology. Thus, Winthrop’s version of “American identity” is based on a shared set of values that will govern the actions of community members. In Matthew Holland’s essay, “Christian Love and the Foundations of American Politics: Winthrop, Jefferson, and Lincoln,” he addresses Winthrop’s unique perspective when he writes:

Recall, he was speaking as a governor, not a congregational minister- and contrary to conventional views of Puritan America there were some distinct and meaningful boundaries between the state and the church. This speech now stands as the Ur-text of an American political tradition that holds agape as a staple principle of civil society. (4)

As Holland points out, Winthrop sets the stage for enacting this new American identity by defining America as a “civil society.” At this time, there was no “America,” only the promise of a new Christian community. From his sermon, though, it is possible to extrapolate how Winthrop defines this community, the beginnings of what would become America. He was also giving the people a way to manage the divides that often cause conflict by giving them a mechanism to handle the societal differences that create tension, based on agape, or Christian fellowship. What is key about Winthrop’s “principle of civil society” is that it is the responsibility of the people. It is up to the individual to consider the “two rules whereby we are to walk one towards another: Justice and Mercy” (Winthrop 167). Winthrop’s carving out of these ideals for American behavior and identity is effective and lasting because it addresses the realistic conflicts that exist. Winthrop writes that “God Almighty in His most holy and wise providence, hath so disposed of the condition of mankind, as in all times some must be rich, some poor, some high and eminent in power and dignity; others mean and in subjection” (165). The material differences among the members of the community are a critical premise of Winthrop’s ideology, especially given that crime is often a result of these differences. Even the question-and-answer structure of Winthrop’s speech replicates the ideals of a civil society. This suggests a civil and democratic approach that resonates with our contemporary understanding of American identity.

<7> Central to Winthrop’s ideals are that they are the responsibility of the individual to enact. In essence, there should be no need for arbitration as each person in his community treats the others as he would treat himself. Winthrop promotes this by articulating an ethic of reciprocity of sorts: “To apply this [law of loving his neighbor as himself] to the works of mercy, this law requires two things: first, that every man afford his help to another in every want or distress; secondly, that he performed this out of the same affection which makes him careful of his own goods” (167). Winthrop’s variation of the “golden rule” demands that neighbor help neighbor, and distribute resources in such a way that will benefit the group over the individual. Further, Winthrop explains that as each member of the group is yoked to the rest, that their strength comes from their togetherness:

Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck, and to provide for our posterity, is to follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God. For this end, we must be knit together, in this work as one man. We must entertain each other in brotherly affection. We must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities, for the supply of others’ necessities. We must uphold a familiar commerce together in all meekness, gentleness, patience and liberality. We must delight in each other; make others’ conditions our own; rejoice together, mourn together, labor and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, as members of the same body. So shall we keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace. (176)

Thus, to avoid disaster, cohesion in all regards–from work to celebration–is critical. Winthrop’s vision calls on his peers to work together, take care of one another, and hold the greater good above the individual. Winthrop emphasizes the logical nature of this imperative when he explains that “the law of nature could give no rules for dealing with enemies, for all are to be considered as friends in the state of innocency, but the Gospel commands love to an enemy” (168). Winthrop uses these Christian principles to elevate the importance of community as well as to govern the rules of individuals that comprise it. Ultimately, Winthrop’s sermon forwards a set of ideals that are both timeless and problematic in their hegemonic values. Central to these “fundamental issues for American national identity” are those established by Winthrop, such as the role of the individual in relation to the community at large.

<8> It is also worth considering the ways in which Winthrop’s sermon defines a community that is well-designed to perpetuate hegemony. Ordained by the ideals of justice and mercy, the community members themselves are positioned as morally right and just, while outsiders are given no consideration within the text. In 1630, it is unlikely that these immigrants knew nothing of the existing settlements nor of the Native American indigenous populations that are described in great detail in Thomas Harriot’s text “A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia” published in 1588. Winthrop’s omission of indigenous people or other communities is significant, especially because new settlers and communities must often rely on help to find resources, navigate new territory, and to survive. Instead, the tenets of “A Model of Christian Charity” serve to privilege the righteous nature of this new community and expose the exclusive foundation of a community from which a dominant culture would arise. The static nature of Winthrop’s ideals and the significant omission of others reinforces the homogenous terrain that–by design–attempts to forestall liminal construction of identity. Definitions of identity in Winthrop’s ideal community are absolutes.

<9> On the other hand, the communities and identities defined in Watchmen are much more complex and reflect variation in both identity and ideology. Moore and Gibbon’s “superhero” characters both embody and diverge from Winthrop’s ideas in ways that reveal the liminal divides created by the tensions between differing interpretations of justice and mercy. As the reader considers each character and his or her motivations and actions, the question of whether these characters functions as a superhero, vigilante, or liminal other complicates their understanding of American identity. In addition to being a trope and epilogue of the text, the question of “who watches the watchmen” prompts readers to consider the diverging ethical approaches to determining what is in the best interest of the community. While the ideology that Winthrop sets forth works to anticipate a wide variety of conflicts, the post-nuclear crisis manufactured by Moore and Gibbons tests this ideology and presents a variety of responses that illuminate different aspects of American identity. In Prince’s article, “Alan Moore’s America: The Liberal Individual and American Identities in Watchmen,” he underscores the significance of the Individual:

First, as highly individuated persons, the Watchmen en masse stress the prominence of this aspect of American identity. Their very existence contributes on a mythological level to the importance placed on individuality in the notion of what it means to be an American. Also, as individuals, they embody ideologically contingent roles in American society, each characterizing a distinct political or economical value, rehearsed as domestic or foreign policy. Yet, this is also problematical; as crime fighters these hyper-individuals act for the putative good of the ‘‘collective.’’ Taken in sum, though, plot and character elements suggest that, even in the face of technological complexity combined with political bungling, the organ of society is portrayed as influenced by individual action. (818)

Prince shows how American identity stresses the importance of the individual in Watchmen, as well as how the “individualism” creates tension with the community ideals of its society. In contrast, in Winthrop’s world it is the duty of the liminal individuals to be subsumed by the community. The ideas and actions that would take place during Winthrop’s time are governed by a strong adherence to Christianity. Conversely, the characters of Watchmen are complicated politically, spiritually, economically, and ideologically, and consequently largely exist in liminal spaces. These differences are illuminated both when the narrative takes up their individual stories and when the characters convene in a group. Seeing these characters work together—and even at odds with each other—serves to highlight the different ways that they straddle their liminal positions.

<10> In Watchmen, these liminal characters attempt to form a communitas first in the form of Minutemen and later as the Watchmen. The names of these groups are historical references “to the American Revolutionary War militia and to the intercontinental ballistic missile in the arsenal of the US Air Force’s Strategic Air Command” (Prince 816). The names are also significant given that these groups were essentially fighting against unsavory elements of American society itself, and are a nod to historical American responses to perceived threats. However, the conventional community (and the lure of personal fame and fortune) represented by American society proves to be the undoing of both of these groups: Sally Jupiter, for example, marries her agent and pursues commercial success and Edward Blake becomes a professional soldier, as employment by the government becomes a way to legitimize his actions. The fate of this communitas is doomed when they are forced to testify in congress and reveal their true identities. The latter band of superheroes had, for the most part, a vision that was more aligned with American values. For example, The second Nite Owl, Rorschach, and Ozymandias are all interested in maintaining safety and national security. However, they depart from Winthrop’s ideals in their lack of community. Winthrop specifically addresses how to handle a “community in peril” by focusing on basing decisions on putting the needs of the community before one’s own (170-1). However, they don’t communicate with one another; the superheroes each work to execute competing strategies for achieving their goals. Moore and Gibbons force the reader to contemplate the complex nature of identity within a post-nuclear community in peril. As the second communitas of Watchmen is disbanded, their individual beliefs about justice and mercy supplant the community ones, and how that affects their notions of “American” identity.

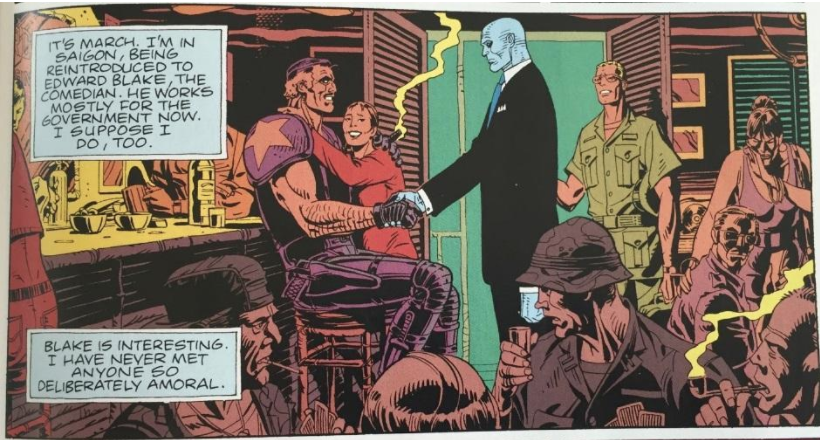

<11> Each of the superhero characters that Moore and Gibbons produce exemplifies, in some way, the American ideals that Winthrop outlines. Based on his actions such as killing a pregnant woman and his attempted rape of Sally Jupiter, Edward Blake is the least sympathetic character in Watchmen. Conversely, he is also symbolic of the iconic patriotism that defines the American Superhero. The murder of Edward Blake, also known as the Comedian, is the impetus for Rorschach’s quest to find the person who is killing the superheroes in Watchmen. Blake’s status as a “superhero” is questionable given his violent nature, and his character prompts readers to consider his own morality. Blake is a particularly complicated figure as he is hired by the United States Government as an independent contractor in Vietnam. While he works to support the community, he does it for enjoyment, rather than a sense of doing what is right; he is a superhero in name and cape only. Another complicating factor is that because the text begins with his death, the reader’s information about Blake is limited to what the other characters in the text choose to reveal. In the panel below, Dr. Manhattan reflects that “Blake is interesting. I have never met anyone so deliberately amoral.” Blake sets in the center of the image, with a large star on his shoulder. The visual image of Blake aligns him with the American flag, and readers are provided information that he is also working for the government. However, as seen in figure 1, he is in contrast with the troops in the picture who are wearing fatigues:

Figure 1 (Chapter 4, 19, panel 4)

As Dr. Manhattan continues to reflect on Blake, he comments that “he suits the climate here, the madness, the pointless butchery” and then suggests that “Blake understands perfectly… and he doesn’t care.” The reader is presented a picture of someone who is simultaneously associated with America, and also unfeeling, uncaring, and disconnected. The image of Blake in Figure 2 confirms this as Blake leverages his version of flamethrower-based “justice” with a maniacal smile on his face, a significant foil to the smiley face of his costume. As Prince notes, “The symbol employed by Blake on his Comedian costume, the “smiley face,’ stands as an icon for this careless chauvinism facilitated by a nihilistic ethical detachment.” (819). Despite his costume, Blake is not working for a larger American community or national purpose–he is working for himself, for personal gain and glory, and even the physical enjoyment of killing and destruction. Blake’s meaningless iconic patriotism is divorced from the ideals of justice and mercy–ironically, the very ideals upon wars are waged. As such, Blake represents an individualism gone awry that is no longer in the service of the community.

Figure 2 (Chapter 4, 19, panels 5 & 6)

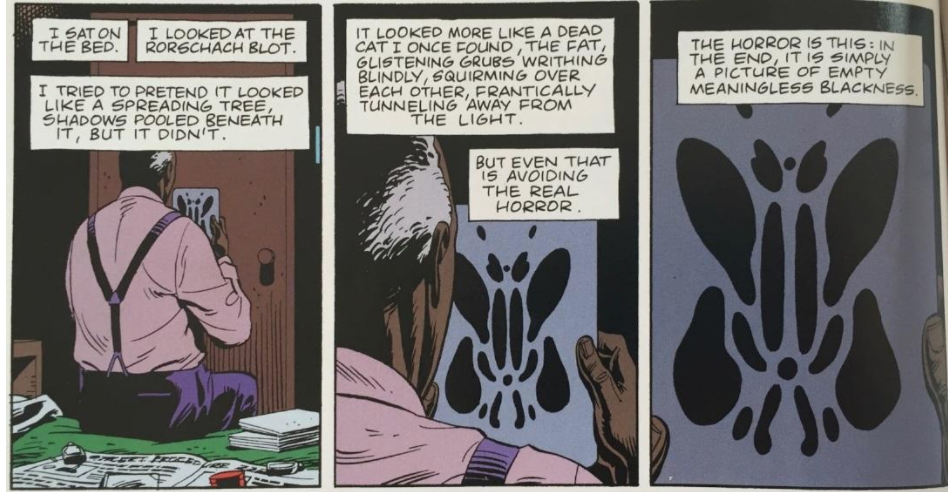

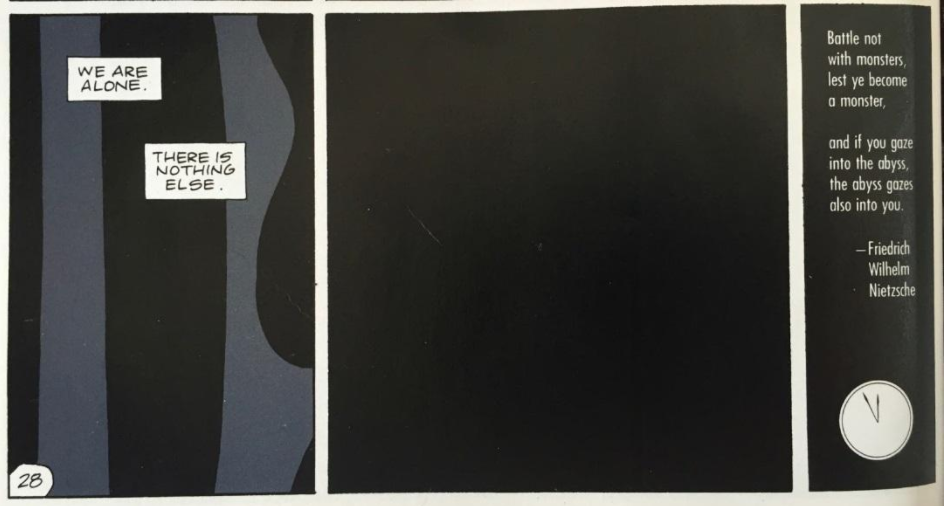

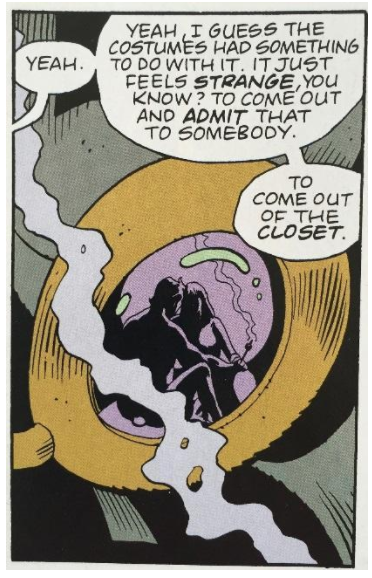

<12> While Edward Blake, or, the Comedian, complicates our understanding of superheroes’ motivations, Rorschach’s motivations are clear while his actions are questionable. The clearest example of this is when Rorschach pursues the child rapist and murderer of six-year-old Blaire Roche (Chapter 6, 18). Rorschach’s intentions in his need for justice are laudable: he is repulsed both by the crime as well as the justice system’s failure to punish the guilty party. Rather than turn him over to the system, Rorschach finds the criminal responsible, chains him to the interior of a building, gives him a hack saw, and commences burning the building down. Rorschach forces the criminal to either saw off his own arm, or die from fire (Chapter 6, 25). To achieve his end of seeking justice, Rorschach engages in unacceptable criminal activities and ultimately denies the criminal both justice and mercy. This response is in sharp contrast to Winthrop’s idea that it is critical for members of the community to love their enemy (168). Rorschach’s actions force readers to question: who determines what is fair, what constitutes justice, and what constitutes mercy? Rorschach’s explanation of his actions to the system-imposed psychoanalyst explains his extreme views: “Existence is random. Has no pattern save what we imagine after staring at it for too long. No meaning save what we choose to impose. This rudderless world is not shaped by vague metaphysical forces. It is not god who kills the children. Not fate that butchers them or destiny that feeds them to the dogs. It’s us. Only us” (Chapter 6, 26). While Rorschach is perhaps the character in the book who demonstrates the greatest compassion for others, despite his own tragic childhood, his rejection of the ideals that Winthrop establishes requires him to create his own framework for establishing order.

<13> Because Rorschach’s own notions of justice, mercy, and community are skewed, he is ultimately incapable of promoting order and being part of a larger, functional community. Readers can see how this absence of mercy is reflected in his relationship, or lack thereof, with his mother. In Winthrop’s text, mercy springs from love, and the mother-child bond of love is used to model one’s relationship with Christ: “So a mother loves her child, because she thoroughly conceives a resemblance of herself in it. Thus it is between the members of Christ. Each discerns, by the work of the spirit, his own image and resemblance in another, and therefore cannot but love him as he loves himself” (Winthrop 173). The development of the ideals that support the foundation of Winthrop’s community are based on the presumed functionality of mother-child relationships. Because Rorschach’s relationship with his mother is flawed, his understanding of justice and mercy are flawed as well. Rorschach’s relationship with his mother results in both self-loathing and anger directed at others, and negatively impacts his ability to create connections within his community, from which he only experiences other forms of rejection: For example, when Rorschach is verbally attacked by a group of boys who use his mother’s shortfalls as a way to bully him, he bites the antagonist’s face in response (Chapter 6, 6-7). Biting the face symbolizes his disconnect with love and mercy: mutilating the face is a mutilation of resemblance between humans. Rorschach is the only one of the Watchmen who wears a mask that obscures all of his facial features. His mask–an ever changing Rorschach test—reflects his disconnect from others.

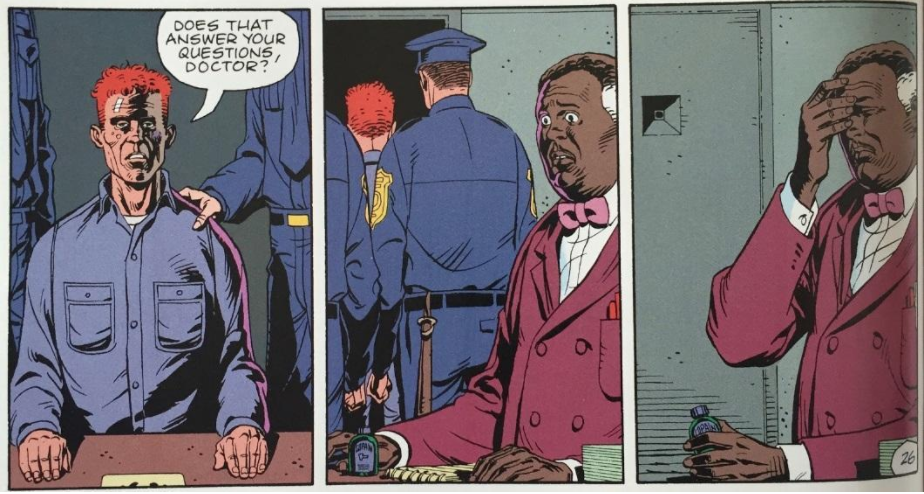

<14> As a consequence of this disconnection from community, Rorschach employs a “no mercy” approach to justice. When he is imprisoned, he does not equate himself to the other prisoners. He warns them, “I’m not locked up in here with you. You’re locked up in here with me” (Chapter 6,13). It becomes clear during his imprisonment that Rorschach has a sophisticated understanding of how people work. This is evidenced as Rorschach flips the script on his psychoanalyst and gets into his head instead: “Other people, down in cells. Behavior more extreme than mine. You don’t spend time any time with them… but then, they’re not famous. Won’t get your name in the journals. You don’t want to make me well. Just want to know what makes me sick” (Chapter 6,11). Prince notes that Rorschach “…is the most uncompromising individual among the Watchmen, exemplified by his sense of integrity, goal directedness, and resistance to indoctrination, chief among these the professed ‘‘cures’’ of psychiatric medicine” (822). After Rorschach discusses his actions with the psychologist (Figure 3), the Psychologist is incapable of responding, and in subsequent panels readers see the impact that Rorschach has on his state of mind (Figure 4 – 5).

Figure 3 ( Chapter 6, 26, panel 7-9)

Figure 4 (Chapter 6, 28, panel 4-6)

Figure 5 (Chapter 6, 28, panel 7-9)

<15> His freedom from accountability to others, his vigilante “outsider” status, are appealing, but unrealistic. Even his accountability to his own super-hero coterie is flawed (Figure 6). The two people who maintain a connection to Rorschach, Laurie and Dan, go out of their way to “save” Rorschach from his imprisonment and are just as surprised by his ungrateful response as Rorschach is by their attempt to rescue him. The inability of these characters to anticipate one another’s reactions to these events is indicative of their disconnect. In the end, it is Rorschach’s disconnect from his community that forces and defines his liminal position. The superhero with whom readers identify and share his ideas of justice, and his sense of “reading” the events of his world is also the biggest outsider: he ostracizes the community that simultaneously rejects him.

Figure 6 (Chapter 8, page 20, panel 4)

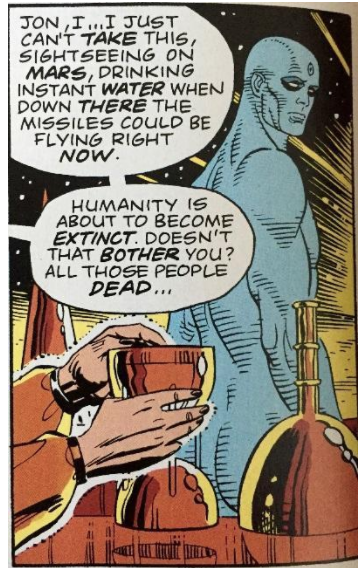

<16> While many of the superhero characters in Moore and Gibbon’s text occupy a liminal American identity, Dr. Manhattan, or, Jon Osterman serves as a distinct contrast as he eschews identity itself. For example, if he is contrasted with Rorschach, their differences come into sharp relief. Whereas Rorschach has a strong sense that he is serving his own personal justice. Dr. Manhattan believes that there are no such things as justice, mercy, or community. The accident that Dr. Manhattan suffered because of his experimentation with nuclear technology suggests that he is aligned with the post-nuclear world and the future. Rather than establishing a liminal identity, he removes himself from the superhero/vigilante continuum altogether. By virtue of his self-imposed absence, Dr. Manhattan is a-liminal–neither apart from nor a part of a community governed by justice and mercy. This absence is a key component of one of the most significant moments in Watchmen when Edward Blake, the Comedian, shoots a pregnant woman (presumably with Blake’s own child) in the presence of Dr. Manhattan. This scene is a particularly important one because it reveals so much about the identity of both superheroes. Blake’s actions are impulsive and focus on his own gratification. More importantly, though, he assumes that the presence of Dr. Manhattan offers a safety net for him. Blake replies to Dr. Manhattan’s assertion that “(she was pregnant. You gunned her down (Chapter 2, 15) by saying “You could have changed the gun into steam or the bullets into mercury or the bottle into snowflakes! You could have teleported either of us to goddamn Australia… but you didn’t lift a finger” (Chapter 2, 15). While Blake’s actions are condemnable, they are based in strong emotions and a desire for gratification. Conversely, Dr. Manhattan’s lack of action demonstrates his distance from the ideals of justice and mercy, and his increasing distance from being part of community of fellow humans. His physical relationships with women are the only thing that seem to keep him (literally) grounded. The media capitalizes on this weakness when they accuse Dr. Manhattan of giving his former girlfriend, Janey Slater, cancer. This causes him to retreat from Laurie, former superhero Sally Jupiter’s daughter and Dr. Manhattan’s most recent love interest. He begins to flail and loses interest in the world around him. This is evidenced below in Chapter 9 when Dr. Manhattan and Laurie are on Mars discussing Laurie’s inability to ignore the problems on Earth:

Figure 7 (Chapter 9, 10, panel 5)

For Laurie, being on Mars and apart from her community is unacceptable. In Figure 7 above, she says, “Jon, I… I just can’t take this, sightseeing on Mars, drinking instant water when down there the missiles could be flying right now. Humanity is about to become extinct. Doesn’t that bother you? All those people dead…” In Figure 8, Dr. Manhattan demonstrates that he does not identify with the community that is on earth. He is an individual detached from the community and as such, no longer has mercy. When he states, “All those generations of struggle, what purpose did they ever achieve,” he can no longer see himself as connected or invested and therefore is unwilling to act. Justice and mercy seem quaint or antiquated, a community (or universe) without them is dangerous–everyone is at risk without empathy. In many ways Jon’s dangerous, nihilistic nature, by way of relief, demonstrates the validity of the tenets of Winthrop’s sermon and his definition of what makes communities work.

Figure 8 (Chapter 9, 10, panel 6)

<17> As a strong contrast to Dr. Manhattan’s other-worldly nature, Dan Drieberg (AKA the second Nite Owl) exists as a typical, often-mundane, ordinary citizen. For example, upon meeting Rorschach who broke into his house and is slurping beans from a can, Drieberg asks him “uh… you want me to heat those up for you or anything” (chapter 1, 11). This small act signifies his adherence to social conventions, such as treating a visitor with hospitality and is in stark contrast to the anti-social behavior of Rorschach. In addition, he also attends The Comedian’s funeral (chapter 2, 3). These actions, though seemingly innocuous, suggest a character who considers others–a value that is privileged in Winthrop’s version of community. Unlike many of his fellow “superheroes,” Drieberg wrestles with feelings of conflict, and as a result he negotiates his liminal identity better than many of his fellow superheroes.

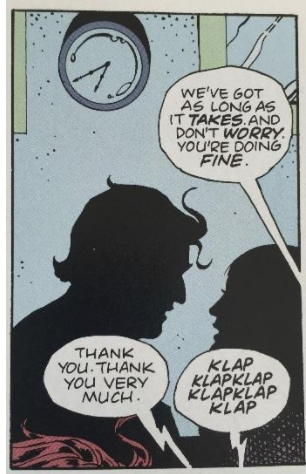

<18> Drieberg seems to be the prototypical superhero that has a clear sense of the balance between justice and mercy. Ironically, the character who seems to be most reasonable and representative of American ideals has chosen not to participate in the practice of superhero vigilante justice. This is in part because of his belief in justice and the systems set in place by the American government. This plot line in surely meant to invoke the House Un-American Activities Committee, which called into the question of the actions of citizens. Because the Keene Act was passed prohibiting the actions of superheroes, Drieberg gives up his position, until his impotence extends beyond the superhero sphere and into his own bedroom. Moore and Gibbon offer a critique of his temporary retirement from acting as a superhero as they pair this action with his sexual impotence. It is only when he puts his mask back on and fires up Archie, his owl-inspired flying vehicle, that he is once again associated with masculinity. In the first three panels below, Gibbons and Moore present a sequence of Laurie initiating a sexual encounter with Drieberg. The background of these first three televisions is a program featuring Ozymandias, who serves as a constant reminder of Drieberg’s inaction. In figure nine, readers see that Laurie Juspeczyk and Dan have given up on fulfillment. The sustained effort and number of panels devoted to this encounter reflects its significance within the text. The constant interjections of the television program remind Drieberg about his choices, his inaction, and ultimately, his failures.

(Chapter 7, page 14, panel 2) |

(Chapter 7, 15, panel 1) |

(Chapter 7, 15, panel 3) |

(Chapter 7, 15, panel 7) |

Figure 9

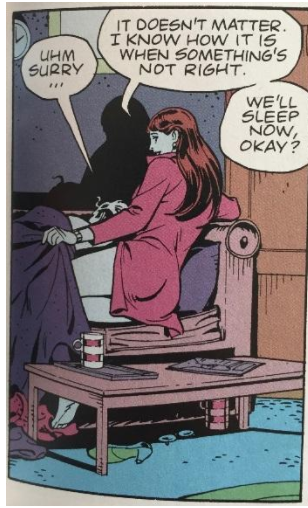

Drieberg’s status as a rule-follower prevents him from enacting justice as a superhero. His liminal identity within the text is particularly significant as he makes a conscious effort to act, thus changing the way that he functions within the text (and the way that readers perceive him). In the middle of the same chapter, Drieberg dreams that he and Laurie kiss, and then shed their skin and reveal their costumes underneath (Chapter 7, 16). Upon waking, Drieberg goes downstairs and is followed by Laurie. Drieberg reveals, “I just had a dream is all. We were kissing, and then this nuclear bomb, it just… we burned up. We were gone. Everything was gone… It’s this war. The feeling that it’s unavoidable. It makes me feel so powerless. So impotent” (Chapter 7, 19). Upon having this conversation, both Juspeczyk and Drieberg put on their costumes and take Archie out for a ride. At the end of the chapter, Drieberg and Juspeczyk find and rescue a group of people trapped on the roof of a burning building; after taking them to safety, readers see the scene below unfold (Figure 10). Drieberg says, “Yeah, I guess the costumes had something to do with it. It just feels strange, to come out and admit that to somebody. To come out of the closet.” In this panel, readers learn that the political turbulence Drieberg originally cites isn’t necessarily the cause of his impotence. Drieberg is caught in a liminal position between what he feels is right and wrong and the systems and community rules that govern (or outlaw) his actions.

(Chapter 7, 28, panel 4) |

(Chapter 7, 28, panel 8) |

Figure 10

<19> Daniel Drieberg is representative of what the reader expects in regards to the superhero’s relationship to justice, community, and mercy. However, his adherence to social norms, and his value of the systems that govern America, result in delay, and utter failure of his mission. The value system that Winthrop forwards can only work if the whole community embraces it. Drieberg, the character who is most associated with Winthrop’s values, is incapable of preventing tragedy because he exists within a community that plays host to varied interpretations and rejections of these ideals.

<20> Whereas Dan Drieberg is the most aligned with Winthrop’s ideals, Adrien Veidt, also known as Ozymandias, is the last and most nefarious of the Watchmen to come into focus. Veidt is presented early in the text as an intelligent and powerful magnate who has capitalized on his successes and is more invested in profiting from his Ozymandias action figures than he is engaging in fighting crime. Veidt is also an important character as he is a symbol of the systematic inequity that Winthrop’s ideals should alleviate: rather than sharing in his fortune as well as his burden of responsibility, Veidt demonstrates what happens when one character takes on all the power and responsibility and is solely responsible for determining how to execute both justice and mercy.

<21> Adrien Veidt’s wealth is important because it seems like the product of a meritocracy. He works to create a “bootstrap” narrative that differentiates himself from others. Veidt’s wealth is also a rejection of the core tenet of Winthrop’s ideology: “We must delight in each other; make others’ conditions our own; rejoice together, mourn together, labor and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, as members of the same body. So shall we keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace” (176). Clearly, Veidt has not made others’ conditions his own. Though he may try to rewrite his narrative as one of independence, his successes are a result of support by others. Nevertheless, Veidt employs his financial achievements to distinguish himself from others. One way that he has made this apparent by his physical locations. As pictured, Veidt enterprises is a giant phallic skyscraper that is emblematic of both power and money, one that dwarfs the iconic Chrysler building in the background of the panel.

Figure 11 (Chapter 1, 17, panel 1)

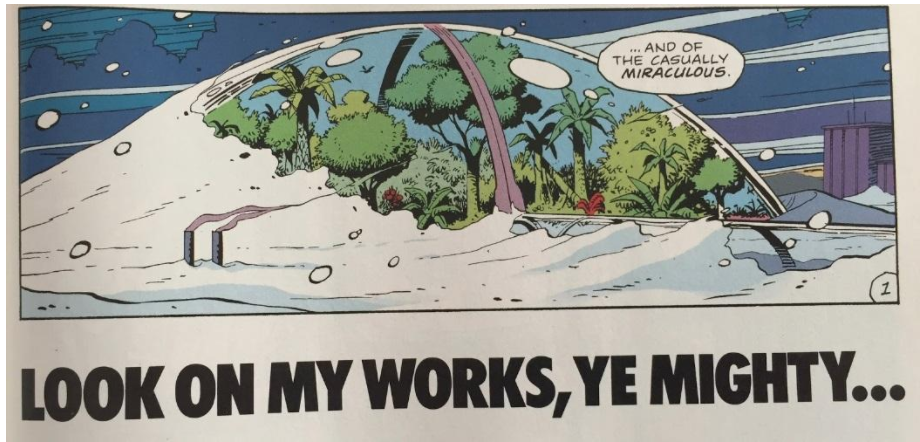

Further, the structure of the building itself reinforces the idea of separation. The window is comprised of windows that are separated by thick borders and the columns below are suggestive of bars that separates the inhabitants from those outside. Similarly, his “vivarium” in Antarctica sets himself apart from the community he claims he is working to save: Whereas the headquarters demonstrates his power and finances, the vivarium represents the extent of his financial fortune. The cost of building a tropical paradise in Antarctica suggests money that goes well beyond the cost of urban office space, even in the most phallic of skyscrapers.

Figure 12 (Chapter 11, 1, panel 7)

The other function of this building is to separate Veidt from a community. Veidt’s decision to kill over three million civilians takes place when he is not within their proximity (Chapter 12, 19). He has found the least habitable environment in which to live as the base command for carrying out his act of terrorism. The intent of Veidt’s actions are not as benevolent as he leads his peers and himself to believe: At the end of Chapter 10, Veidt is planning to market action figures of himself and the key players of the event he has planned, planning a television show, and making recommendations about the marketing of key elements of his Veidt corporation, all the while fully knowing how his plans will affect the market. For example, the following excerpt from a letter to the director of his Cosmetics and Toiletries division shows how he is adjusting his marketing strategies:

While this marketing strategy is certainly relevant and indeed successful in a context of social upheaval, I feel we must begin to take into account the fact that one way or another, such conditions cannot endure indefinitely. Simply put, the current circumstances ou[r] civilization find itself immersed in will either lead to war, or they won’t. If they lead to war, our best plans become irrelevant. If peace endures, I contend that a new surge of social optimism is likely, necessitating a new image for Veidt cosmetics, geared to a new consumer. (Chapter 10, 31)

He is trading on inside knowledge, making decisions based on a market that he is going to manipulate in a key way without any personal connection or stake.

<22> The ideas that Winthrop forwards in his text don’t take into account a world that is strongly based in capitalism. Nearly all of the superheroes who exist in The Watchmen embody their superhero identity; even Dan Drieberg has problems when he temporarily rejects that identity. Veidt, however, uses his two separate identities strategically for personal gain within capitalist society. Veidt’s money and influence allow him to (pretend to) be a benevolent benefactor, all the while he is manipulating those around him. As Ozymandias, Veidt narrates his quest to Rorschach and the second Nite Owl, attempting to explain how he was “determined to measure [his] success against [Alexander of Macedonia]”: “Firstly, I gave away my inheritance to demonstrate the possibility of achieving anything, starting from nothing” (Chapter 11, 8) To the extent that he believes his successes are indicative of his righteousness, he also seems to develop a “god complex.” Captain Metropolis says “Somebody’s got to save the world” (Chapter 11,19)–Veidt decides this will be him. He begins with the goal of “improv[ing] the world” by ending injustice (Chapter 11, 18). However, like his fellow disillusioned peers, he concludes that his actions have little lasting impact, and that there were larger problems he was not able to change: “I fought only the symptoms, leaving the disease itself unchecked” (Chapter 11, 19). He decides to take on a singular journey of study to address this change, and ends up formulating a plan: “Unable to unite the world by conquest… Alexander’s method… I would trick it; frighten it towards salvation with the history’s greatest practical joke” (Chapter 11, 24). While this is the justification that Ozymandias provides, he conveniently leaves out the financial gains that Veidt’s corporation will incur as a result.Ultimately, Veidt/Ozymandias’ motivations are complex and reflect both self-interest and interest in others as evidenced by a convoluted way of attempting to prevent nuclear war. The self-interested financial successes that Veidt manipulates undercut the benevolent and utilitarian justifications that his alter ego Ozymandias narrates, reflecting a divide between him and his community, and ultimately between him and his alter-superhero-ego as well.

<23> John Winthrop’s sermon sets a standard of ideals for his new community that shapes the identity of these superheroes in a fictional 1985 version of America. Each of the characters that emerges in The Watchmen exists in a liminal position in regards to their superhero identity. Edward Blake lacking mercy, Daniel Drieberg’s blind obedience to the government, Rorschach’s tenuous connection to community, Dr. Manhattan’s rejection of justice, mercy, and community, and Adrien Veidt’s rejection of his community for capitalistic and self-interested ends–each of these characters attempts to fulfill the role of superhero from a liminal position, and ultimately fails. Adrien Veidt, in his attempt to “save” the country from nuclear war, annihilates half the population of New York city. This simultaneously represents the greatest triumph and failure. Veidt succeeds in the task at hand, and ultimately his community loses.

<24> In theory, Winthrop’s values persist–they are the tenets of the status quo and the mythology of American culture that many of the Watchmen rely on and use to justify their actions. In practice, the characters of the Watchmen use these ideals but don’t embody them–they inhabit the spaces between and among them. However, the text ends with a series of defeats. The superhero community is nearly extinct. The Comedian, the first Nite Owl, Minutemen, Moloch the “villain” –they are all dead. Adrien Veidt is able to successfully execute his plan, killing Rorschach forcing Dan Drieberg and Laurie Juspeczyk and even Dr. Manhattan into exile. Moore and Gibbons, by virtue of this ending, force the reader to consider a pessimistic view of American values and identity. The characters with the most “American values” as established by Winthrop are unable to prevent a crisis from happening on American soil. The competing ideologies that are represented via characters who embody these liminal identities are both relatable and ineffective. While it presents a somewhat pessimistic view of American identity, Watchmen also demonstrates the possibilities and processes afforded by liminal spaces–identity itself, and our (re)constructions of it, is a narrative and dialectic process.

Works Cited

Dittmer, Jason. “Captain America’s Empire: Reflections on Identity, Popular Culture, and Post 9/11 Geopolitics.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 95.3 (2005): 626-643. Academic Search Complete. Web. 7 Jan 2016.

Harriot, Thomas. “From a Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Gen. ed. Nina Baym. 5th ed. Vol. A. New York: Norton, 1998. 77-83. Print.

Holland, Matthew S. “Christian Love and the Foundations of American Politics: Winthrop, Jefferson, and Lincoln.” Conference Papers–New England Political Science Association. (2004): 1-27). Academic Search Complete. Web. 7 Jan. 2016.

Moore, Alan, and Dave Gibbons. Watchmen. New York: DC Comics, 1987. Print.

Prince, Michael. “Alan Moore’s America: The Liberal Individual and American Identities in Watchmen.” Journal of Popular Culture. 44.4 (2011): 815-830. Academic Search Complete. Web. 7 January 2016.

Schweitzer, Ivy. “John Winthrop’s ‘Model’ of American Affiliation.” Early American Literature. 40.3 (2005): 441-469. Academic Search Complete Web. 7 January 2016.

Turner, Victor. “Liminality and Communitas” The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co, 1966.

Winthrop, John. “A Model of Christian Charity.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Gen. ed. Nina Baym. 8th ed. Vol. A. New York: Norton, 2012. 166-177. Print.