Reconstruction 6.2 (Spring 2006)

Return to Contents»

"If your God has really spoken to you...then all the world must hear it": The Discourses of Revelation and Satire in Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses / Conrad William

Abstract: In his essay, “Is Nothing Sacred?”, Salman Rushdie lays out a place for literature as an arena in which various perspectives may interact. He thereby provides a context for the controversy regarding his books, most particularly The Satanic Verses. Depite his claims, however, literature, as Rushdie conceives it, operates not simply as an arena for discourse but similarly as a rule-maker, controlling the discourse which operates within its bounds. The Satanic Verses, in particular, suggests that revelation as it passes through unstable and hybrid human language loses its authority and power to speak purely or dogmatically. In so doing, Rushdie questions not only the purity of divine revelation, but also the integrity of poetic and fictional language, indicating that both serve as a kind of will to power or will to truth. In his criticism, then, Rushdie ironically sets up a place of privilege for literature that his novel The Satanic Verses essentially deconstructs. In this ironic tension, he demonstrates the uncompromisable boundaries existing between purportedly atheological or secular domains of discourse and theological or revelationally-based domains of discourse. In other words, the pressupposition that God has not (or could not have) spoken and the presupposition that he has (or could have) spoken are inextricably at odds with one another and thus fight for the same territory in defining the nature of all discourse.

<1> Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses has drawn multiple forms of criticism for its religious content. Though, in one sense, the book is about the migrant’s experience, it is hard to deny that the work is likewise an exploration of the very nature of divine revelation, or more particularly, human understanding of that revelation. Rushdie himself indicates this, while simultaneously claiming that he attempted to avoid offense in his novel. However he frames it in his external criticism, the book itself indicates the inherent tension between a religious and a naturalistic worldview. In a sense, Rushdie’s use of the satanic verses in the life of Mohammed and formation of the Quran implicitly asks the same question the serpent asked of Eve in the Garden “Did God really say?” (Gen. 3:1 NIV) of all purported revelation. However legitimate the question, it remains a challenge to all religions adhering to divine revelation, and in this respect is an offense.

<2> Offense though it be, in this case it seems a productive one. Even as Rushdie challenges the nature of religion, he also exposes the cracks of a postmodern worldview. Indeed, as is apparent in the novel and Rushdie’s comments about the novel, literature becomes a substitute of sorts for the place once held by theology [1]. Yet, literature, even as “the arena of discourse,” to use Rushdie’s metaphor (Imaginary Homelands 427), still enacts its own rules of language by which it controls the conversation in a way akin to theological orthodoxy. In light of this tension, even contradiction, this essay aims to explore how Rushdie problematizes the concept of revelation in his work The Satanic Verses while similarly problematizing the role of (postmodern) literature as he conceives it [2]. In so doing, I hope to expose how Rushdie fails to provide a viable place for revelation within his conceived pluralism, but instead demonstrates how belief and unbelief remain in an uncompromisable deadlock for the “arena of discourse.” To demonstrate this, I will examine from a predominately Christian (specifically a Protestant evangelical) view of revelation 1) how the use of translation in the novel exposes the naturalistic assumptions of Rushdie’s hybridity and 2) how, contrary to Rushdie’s claims, satire as literature acts as an exclusivising substitute for religious discourse.

Translation: Communicating or Creating the Divine Message?

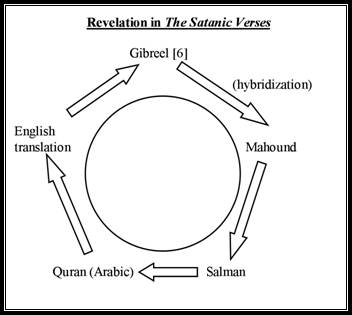

<3> As with other metaphors in the book, Rushdie’s image of “translation” often operates as a broader metaphor for the migrant’s experience (cf. Mann). Hence, in Imaginary Homelands he points out how the Latin origin of “translation” literally means “bearing across” (17). Beyond the migratory implications, however, The Satanic Verses wrestle with this term in a more literal fashion through the translation of purported revelation into human language. The issue of hybridity (i.e. the diversified origins of an entity) remains at the heart of this linguistic translation, but, significantly, the circle of translation Rushdie demonstrates exposes the secular boundaries of the book.

<4> One of the more puzzling scenes of the novel (and there are many) comes in Gibreel’s schizophrenic movement from self-proclaimed archangel to groveling beggar at Allie Cone’s door. In the center of this movement is a catalytic statement on translation – catalytic both for Gibreel and my understanding of the text. As Gibreel is brooding over the dangers of ambiguity in England, he considers a passage from the Quran. I quote the whole context for its importance:

“Clarity, clarity, at all costs clarity! – This Shaitan was no fallen angel. – Forget those son-of-the-morning fictions; this was no good guy gone bad, but pure evil. Truth was, he wasn’t an angel at all! – ‘He was of the djinn, so he transgressed.’ – Quran 18:50, there it was as plain as the day. – How much more straightforward this version was! How much more practical, down-to-earth, comprehensible! – Iblis/Shaitan standing for the darkness, Gibreel for the light. – Out, out with these sentimentalities: joining, locking together, love. Seek and destroy and that was all” (353).

Here Gibreel finds the warrant he needs (desires?) for a fundamental distinction between good and evil. To do so, however, he relies upon what he claims as a “more practical, down-to-earth, comprehensible” translation of the Arabic text. Significant about this translation is that it ties Shaitan’s (aka Satan’s) transgression directly to his condition as a djinn. For instance, another translation by Mushaf Al-Madinah leaves the relationship between Shaitan’s actions and nature more ambiguous: “He was/ One of the Jinns and he/ Broke the command/ Of his Lord” (Surah 18:50). Here, however, Shaitan’s essential nature determines his actions. In this sense, the text is rather Manicheist (or dualist – see Francois 305-308); evil and good act as eternal opponents of one another. As Gibreel interprets it, Shaitan was perpetually evil; he never fell from the good to become evil. This enables him to escape the dilemma of compassion for a fallen creature and look upon Shaitan, in this case his representative – Chamcha – with hatred alone. For our purposes, the use of the translation is primary, for, as we shall see, it establishes the final link in what forms an unbroken chain of interpretation and hybridity.

<5> Rushdie’s use of translation here brings forward a central aspect of translation in general, namely, the importance of the original. A translation, it is supposed, aims at communicating the message of one text into another language without losing too much of its message in the process. But, as Homi Bhahba says, “The transfer of meaning can never be total between systems of meaning” (163). Elsewhere, Rushdie suggests that one might gain things in the process of translation even if some is lost (Shame 23; cf. Imaginary Homelands 17). Central to both understandings is what role the original plays, or better the origin of the “original”.

<6> In The Satanic Verses, the source of the original is the precise problem around which the book is centered, for in effect the origin is obscured beyond recognition. According to Islam, of course, the origin is Allah, but in The Satanic Verses Gibreel, as archangel, does not know where he gets the inspiration for what he recites. In fact, he suspects that it comes more from Mahound than any other source (“we all know how my mouth got worked” 123). Indeed, Allah is strikingly absent from the revelation: “He never turns up.... The one it’s all about, Allah Ishvar God. Absent as ever while we writhe and suffer in his name” (111). Salman Farsi shares his suspicion in his observations about the business language that runs through the revelation. He notes “how excessively convenient it was that he should have come up with such a very businesslike arch-angel, who handed down the management decisions of this highly corporate, if non-corporeal, God” (364).

<7> The question, however, of origin is not left simply with Mahound, as if he were the origin of the Quran. Mahound (as with Mohammed) cannot write, so he must recite the verses to a scribe, in this case Salman the Persian. Strikingly, Salman becomes another source of the Quran, as he changes words here and there to test the nature of Mahound’s revelatory words. Indeed, Salman describes his task as “writing the Revelation” (368), a statement indicating more than his simple transcription of the oral text. So, at this point, we have three stated sources for the Quran, each of whom, it is implied, forms his own kind of revelation through his words. When we consider, then, Gibreel’s exegesis of Surah 18:50, we are given one more – the translation of the Quran (as perhaps transcribed by Salman) into English. Hence, the revelation goes full circle – from Gibreel as archangel in Jahilia back to Gibreel as presumed archangel in London.

<8> Returning to the question of origin, we see that it is both multiple and significantly self-contained. The multiplicity of the revelation’s origin effectively obscures and lends it its power. Simona Sawhney’s discussion of the alleged satanic verses are insightful in regard to the portrayal of the whole Quranic revelation in the book:

“If the text continually draws attention to its own inability to name the source of utterance,... then by this very gesture it points toward that which perhaps defines it as a text—that is, as a literary rather than revealed text.... [A] story like that of the satanic verses can only circulate by veiling its sources: its power derives precisely from its lack of authorization” (266).

In this sense, the multiplicity lends the text power and indicates what Rushdie’s narrator says in Shame – “something is gained in translation” (23).

<9> We must notice as well, however, that the revelation in The Satanic Verses operates as a human construct; its power stems not from a divine origin but from the claim of divine origin, a claim which is maintained by the “veiling of sources.” Sawhney proposes that the novel asks us “who really speaks when the archangel speaks?”(263). The answer, according to the above is everybody (or at least five people: Gibreel as giver of the recitation, Mahound, Salman the Persian, the English translator, and Gibreel as interpreter in London). Furthermore, since everybody speaks, ultimate authority is lost. As M. Keith Booker writes, citing Bakhtin, “No word can have unquestionable authority, because all words inherently contain the potential echoes of responses from opposing voices” (989).

<10> Hence, positing the text as a human contruct as the novel does also indicates that the text is self-contained. In other words, it is only a human construction; no divine influence may be found. This is consistent with what Rushdie says about the text in his essay, “In Good Faith”:

“I set out to explore, through the process of fiction, the nature of revelation and the power of faith. The mystical, revelatory experience is quite clearly a genuine one. This statement poses a problem for the non-believer: if we accept that the mystic, the prophet, is sincerely undergoing some sort of transcendent experience, but we cannot believe in a supernatural world, then what is going on?” (408).

Rushdie indicates, then, that The Satanic Verses are an exploration of revelation from a position of disbelief. In this regard, the analysis above has shown precisely what Rushdie sees going on: the text passes through numerous translations gaining ironic power through each change, but always without reference to any divine origin.

<11> This last point is important for it exposes some possible misreadings of the text which mislocate the unnegotiable tensions between the discourses of revelation and literature. Brian Finney, for instance, writes, “Entry into the world of language entails compromises and ambiguities that accompany imperfection, a fact that believers in scripture deny” (76). Problematic to Finney’s construction here is not the ambiguity of language, but his claim that revelation-based religion necessarily denies that ambiguity [3]. We must perhaps draw some distinctions here between Islam and other word-based religions, such as Christianity and Judaism. Islam’s view of revelation depends heavily upon a dictation theory of inspiration, i. e. every word of the Quran was spoken to Mohammed and he recorded through a scribe every word. Hence, though translations of the Quran are available (sometimes described as “the message” rather than a “translation”), they are less valued because only the Arabic version contains the literal words of God. Christianity and Judaism, while also having some passages of dictation (e.g. the Law given to Moses and perhaps the words of Yahweh through the prophets) has generally allowed for the imprecision of translation as an analogical representation of the divine word [4]. That is, belief in revelation need not mean a rejection of linguistic ambiguity. Indeed, John Frame, a rather conservative Protestant theologian, speaks similarly to Finney in his book on epistemology, The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God, when he states: “Human language is not an instrument of absolute precision” (216). Following this statement, Frame proceeds to list numerous causes for linguistic ambiguity without relinquishing the authority of the biblical text. One need not deny ambiguity to believe in revealed scripture.

<12> Distinctive to Rushdie’s work is not his demonstration of language’s hybridity nor even revelation’s hybridity, but the presupposition that no divine source may be found amidst the hybrid sources of the text. Rushdie’s apparent answer to Salman’s question, “if my poor words could not be distinguished from the Revelation by God’s own messenger, then what did that mean?” (367) must simply be, “there are no divine words.” Rushdie takes his epistemological problem (how does one discern the divine words?) and solves it with a naturalistic solution, namely, since there is ambiguity, there must be no divine revelation.

<13 This construction makes for a radically different “arena of discourse” than a theologically grounded one. Instead of sifting through words to discern the divine, one presumes that nothing of the divine can be found because one is sifting. The contrast between a supernatural view of revelation (in this instance, a primarily Christian image, since that is the one with which I am most familiar; see footnote [5]) and Rushdie’s might be demonstrated by Figure 1.

Figure 1 [6]

Both systems recognize that with each translation a hybridity may be created. Within the supernatural paradigm, as I construe it, the metaphorical/analogical link between God and the written word ought not be described as an erroneous hybridization of the divine intent. Rather, it indicates the necessity that all revelation of God must be translated into human metaphor. As Michael Horton puts it, “All of God’s self-revelation is analogical, not just some of it.... Transcendence and immanence become inextricably bound up with the divine drama of redemption” (210; his emphasis). While maintaining the truth of revelation, Horton denies that humans can have archetypal knowledge, i.e. absolute knowledge as God himelf knows. In this respect, written revelation is always analogical and anthropomorphic, but nevertheless correct.

<14> In contrast to the supernatural view, the account of revelation in The Satanic Verses denies that any perfect, pure, or even analogical truth [7] may be found amidst that hybridity. The revelation operates in a contained circle with each translation offering new innovations and perhaps lending more power to the original revelation itself. Yet, throughout, the construction disallows the possible intrusion of an ultimate, uncreated divine source. In this sense, Rushdie denies the condition and the subsequent result of Abu Simbel’s call to Mahound: “If your God has really spoken to you… then all the world must hear it” (114). In other words, he rules out the ideas that God has spoken, and hence, shuts off one place for dialogue.

<15> The two positions remain at uncompromisable odds. Put another way, neither position can compromise without essentially becoming the other system. Admittedly, I am in danger of creating an absolutized binary, but in this case I believe the binary holds true. Francois puts it this way: “In the Verses, Rushdie seems to uphold the radically materialistic view that, far from being a necessary component of culture, religion is irretrievably at loggerheads with it” (317) [8]. At its heart, the distinction turns on whether phenomenal analysis must be done purely on naturalistic grounds or if supernatural presuppositions may be allowed. The skeptic or naturalist, I am suggesting, will always find skepticism and naturalism. The super-naturalist, likewise, will find supernatural causes at the root of all phenomena. Rushdie himself illustrates this point with the ending to “The Parting of the Arabian Sea.” The police insist that the sea did not part and people died: “Already the drowned bodies are floating to shore, swollen like balloons and stinking like hell. If you go on lying we will take you and stick your nose in the truth” (501) Sarpanch Muhammad Din, on the other hand insists, “You can show me whatever you want… But I still saw what I saw” (501). Those who believed saw the parting, while those who disbelieved saw only death. Bridging the gap, it seems, requires acceptance of the other’s presuppositions, and thereby, cannot be done without a fundamental shift from one’s own position.

Satire as Privilege

<16> The second place we see the uncompromisable divide between revelation-based discourse and Rushdie’s literary discourse comes in the encounter between Baal the Satirist and Mahound the Prophet. Admittedly, this section poses difficulties for it remains too easy to make this a simple opposition between Rushdie and religion. Though such a divide exists, it is anything but simple. Nevertheless, these sections of the book (“Mahound” and “Return to Jahilia”) both demonstrate Rushdie’s ideas on both the sacred and literature’s engagement of the sacred and indicate the cracks in his thought.

<17> Before dealing directly with Baal, it will be necessary to see how the apparent will to power of the other characters in Jahilia privilege Baal as satirist. We are first introduced to Baal through Abu Simbel, the Grandee of Jahilia. Significantly, the Grandee approaches Baal because he fears Mahound’s potential power. He wants to utilize Baal’s satire (i.e. his words) to subvert Mahound. The ploy is only mildly successful and primarily operates within the narrative to set up the opposition between Baal and Mahound, for it is at this time (only because of Abu Simbel’s extortion) that Baal begins his satirical attacks on Mahound. Nevertheless, Simbel’s temporary success over Mahound is gained less through Baal than through the compromise he elicits from Mahound over monotheism. He procurs this compromise – however short-term – through words. So, from the start we see how language becomes a broker of power for those who wish to use it to control.

<18> Other powers in Jahilia similarly use language to gain and maintain power. Prior to Mahound’s return, we read that Hind has gained control over Jahilia through her “bulls, which were refusals of time, of history, of age, which sang the city’s magnificence and defied the garbage and decrepitude of the streets” (361). In other words, Hind (acting as a type of Imam and Margaret Thatcher) solidifies her reign through deceit, via claims of grandeur that run counter to physical evidence. Again, these claims are made through (written) words, “posters,” which the narrator tells us “were more influential than any poet’s verses” (361).Baal acts as an opposing force to this power; even though he fails to write against Hind, Baal alone refuses to believe these claims.

<19> Salman the Persian, though not owning any power of his own, likewise attempts a use of words to gain power. It is tempting to classify him as a satirist with Baal, and in many instances this is appropriate, but one aspect of his motive for writing sets him apart from Baal – namely, his account of Mahound’s failures includes repeated statements that indicate a personal vendetta. Salman only begins his critique of Mahound after he has failed to gain fame for his strategic defense of Yathrib (365-366). Hence, unlike Baal, Salman undermines Mahound because of his desire for power within Mahound’s army.

<20> The final arbiter of power, of course, is Mahound. Once again, his attainment of power comes through words. Salman ridicules this, pointing out how Mahound conveniently enacts rules in order to bolster his preferences (366). Ridiculed or not, he leaves Jahilia in defeat, but returns with power and a large body of “rules, rules, rules” (363). Through these rules, he defines every aspect of existence from “how much to eat” to “how deeply they should sleep” (364). Mahound’s ultimate success in using these rules to reign over Jahilia establishes his confrontation with Baal, that is, with satire.

<21> In this accounting of power through language, Baal alone seems to act independently of the power motive (with the significant exception of his hesitant employment by the Grandee). In this regard, satire finds a privileged place amongst the competing languages of the text. But, privileging satire becomes difficult because satire destabilizes itself in its privileged position of opposition. Srinivas Aravamudan writes, “I would argue that the contextual principle of satire, its essential instability, is rather always implicated within the slippery slope of eternal substitution, a logic that often leads to the self-destruction of the authorial persona in satire, his ultimate disappearance...” (12). Satire loves, in brief, to subvert and, thus, requires “law” in order to do so.

<22> Baal exemplifies this need of law in his novel by his waning literary achievements during Mahound’s absence. When he opposes nothing or even just Hind, he writes only “failed art” (370). Once Mahound returns, however, and gains apparently absolute control over Jahilia, Baal’s poetry begins to thrive once again. Significantly, the power of his poetry comes from his opposition to monotheism. Perhaps, then, the reason Baal fails to adamately oppose Hind is because her religion is fundamentally polytheistic. Only when monotheism dominates does Baal find a worthy adversary to his satire. Indeed, the text indicates such an ironic union between Baal and Mahound: “[Baal] began stumbingly, to move beyond the idea of gods and leaders and rules, and to perceive that his story was so mixed up with Mahound’s that some great resolution was necessary” (379). This need for resolution supplies our entry into satire’s internal contradiction. For satire’s position as opposition must continually struggle against its own form of monotheism. To reverse Aravamudan’s question “could there be a polytheistic blasphemy lurking under every monotheism?” we must ask, “could there by a resolute monotheism lurking underneath every polytheistic blasphemy?” (12). Or, to put it in Baal’s terms, “What happens, [Satirist], when you win?” (369). More directly, how does satire reign when it controls discourse?

<23> Conveniently, Rushdie offers us insight into this question through Baal’s successful imitation of Mahound’s harem. As Aravamudan has shown, Baal’s mock-harem acts as a substitute for Mahound’s real harem, and thus acts parasitically (12). But in so doing, Baal himself cannot avoid becoming an imitation of Mahound, even if he insists on retaining his name, and in this way imposes his own kind of rules. For instance, when Salman mocks Mahound’s pragmatic revelation, Baal defends the Prophet’s practices. It may be that in this instance, Salman alone acts as pure satire while Baal has become too wrapped up in his mock-reality that he forget is supposed to be mocking reality. Even Baal’s transformation indicates the propensity to rule after one has gained some measure of control, and it would seem that not even satire remains immune from this propensity.

<24> More poignant to our discussion is how satire’s position of opposition sets up an alternative form of revelation. Once Baal has occupied Mahound’s place as husband, he also begins to receive revelation. Indeed, the image Baal envisions of his muse is akin to Gibreel’s experience with Mahound. He describes the experience as if he saw himself “standing beside” himself, speaking the verses on command (385), just as Gibreel dreamt that Mahound was his “other self” working his mouth to speak the recitation (110). Hence, Sawhney’s following description of literature becomes lived out through Baal’s satire: “Literature cannot conceal its own desire to become revelation, even while its mode of narration mocks its claim to the authority of truth.” (272). Therefore, even privileged satire becomes a broker of power despite its continual opposition to hegemony.

<25> Moreover, even as a kind of revelation, satire remains in an unstable, paradoxical position, for its only success comes in tearing down, not in building up. Herein lies the irony of Rushdie’s construction: the competing languages leave all in ruins and fail to establish any positive formation. This happens because of satire’s consistent opposition to the univocal. Indeed, the univocal [9] remains the one thing the tyranny of satire must rule out.

<26> Another way to formulate satire’s privileged place in Rushdie’s novel is as a place of discourse. In “Is Nothing Sacred?,” Rushdie provides an intriguing metaphor to explicate the place of literature in society. He describes a house which is “in fairly bad condition” but acceptable. It is full of bullies, friends, strangers, and lots of activity. It also contains certain inconspicuous rooms in which voices can be heard within one’s own head that discuss the house and its inhabitants. “Some are bitchy. Some are loving. Some are funny. Some are sad. The most interesting voices are all these things at once” (428). The room provides comfort, entertainment, and insight to nearly all of the house’s inhabitants. Rushdie then imagines that the rooms are gone one day and the house becomes a prison. The rooms, he suggests, are literature, “the one place in any society where, within the secrecy of our own heads, we can hear voices talking about everything in every possible way” (429; emphasis added). Preserving this arena of discourse is necessary to prevent the world from becoming a prison.

<27> Earlier in the essay, Rushdie argues that literature “tells us there are no rules. It hands down no commandments” (423). As we press this statement, however, we discover that Rushdie has undermined his own claims. Baal the Satirist, after all, acts as the literature of the novel. His primary interest is maintaining plurality – that is another way of saying he wants to preserve discourse – and then acts as one example of that discourse. Hence, his peculiar opposition to Mahound’s monotheism indicates the primary rule upon which the arena of literature, as Rushdie constitutes it, is established: no one discourse may speak absolutely. Or to put it another way, no one discourse may be privileged as containing ultimate authority. In this respect, the arena of discourse, like the image of translation discussed in the first half of this essay, presumes naturalism. No divine, authoritative discourse may be found because we presume that none exists. For, if any divine discourse existed, it would warrant a privileged place.

<28> A number of critics have pointed out the inherent tension, contradiction even, created by the privileged place Rushdie grants literature. Speaking of pluralism in particular, Pnina Werbner writes, “[Just] as a singular, rule-bound, divine vision tolerates no pluralistic alternatives, so, too, tolerant pluralism, especially one grounded in unbounded emotion alone, cannot encompass singular vision, thus contradicting its claims to universal tolerance” (66). A more incisive critique comes from Finney. He writes, “But just how neutral is a discourse that controls? In its postmodern form is not fictional discourse itself competing for dominance with the other discursive formations it seeks to incorporate within its all-embracing grasp?” (70). Finney’s question makes its point: literature as a discourse (even a purported arena of discourse) defines its own rules for discourse. In the terms of Rushdie’s novel, just as Abu Simbel, Hind, Salman, and Mahound use language to broker power, so also does Baal. His role as a “purely” disarming discourse does not exclude him from creating boundaries through language. Literature, like religion, similarly defines things as “so and not thus” (354; original emphasis).

<29> Finney’s argument in this regard provides further insight into the problematic nature of pluralism in that he himself struggles against privileging any discourse. His complaint against Rushdie concerns Rushdie’s privileging of certain meta-narratives (even if the narrative is literature) and not the privileging of the wrong narrative. He poses the question, “Why does [the decentered discourse of postmodern literature’s] plurality and fragmentation make it preferable to a unitary master narrative?” (86). He answers that it is not preferable; it may be more comprehensive and different, but not superior. Finney’s solution, however, operates under the same naturalistic boundaries as Rushdie’s. To his credit, he does allow for the possibility that a univocal position might actually be superior, but in refusing the possibility of discovering that and allowing it to reign, he operates within the same closed circle depicted in my section on translation (see Figure 1). This tension within both Finney and The Satanic Verses “illustrates,” as Sawhney puts it, “among other things, that the death of God has left us haunted by a bewildering ghost whom we can no longer name” (255). Or, perhaps more accurately put, within pluralism we are left with a ghost we refuse to name for fear of logocentrism.

<30> One way to move forward on this issue and demonstrate the union between satire and literature is to ask about the teleology of the purported “arena of discourse.” I do not deny that revelational religion similarly defines rules for discourse. Examining their respective aims, however, should help expose how the two “arenas” remain at uncompromisable odds. Again, in “Is Nothing Sacred?,” Rushdie describes literature’s sole claim: “the right to be the stage upon which the great debates of society can be conducted” (420). We must ask for what purpose such debates are conducted? In essence, Rushdie must answer that it is for the debate itself. As with satire, in this position of debate, literature continues to tear down, for Rushdie rules out the possibility that any one discourse might win the debate in any absolute sense. This is a view, however, which presumes that the existence of divine discourse provides for such a stage in order that the divine voice might be discerned, the very thing Rushdie’s stage disallows.

<31> Rushdie’s image of a seemingly neutral stage may be misleading. His stage supplies each performer with an opportunity to speak. In so doing, he elevates the position of each individual voice, for they are all presumed to be equal. As Baal subverts Mahound’s position in order to disallow anyone’s supremacy, so this stage aims at the subversion of all absolutes. This is all well and good if no voice truly is definitive of all other voices. But if any one voice warrants definitive power, it will not gain it on Rushdie’s stage. One voice, after all, has already spoken on this stage, the one that rules out the place for the absolute. Rushdie’s stage, in other words, has rules; they are simply different rules than those who admittedly privilege a purported divine voice (revelation) above human ones.

Conclusion

<32> Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses sets up an intriguing exploration, even an indictment of the reliability of language. In particular, the work demonstrates how revelation as it passes through unstable and hybrid human language loses its authority and power to speak purely or dogmatically. In so doing, he questions not only the purity of divine revelation, but also the integrity of poetic and fictional language as a similar kind of will to power or will to truth. In spite of Rushdie’s claims elsewhere (e.g. “Is Nothing Sacred?”), literature, as Rushdie conceives it, operates not simply as an arena for discourse but similarly as a rule-maker, controlling the discourse which operates within its bounds. Hence, in his criticism, Rushdie ironically sets up a place of privilege for literature even as his novel The Satanic Verses deconstructs that place of privilege. In this ironic tension, he demonstrates the uncompromisable boundaries existing between purportedly atheological or secular domains of discourse and theological or revelationally-based domains of discourse. In other words, the pressupposition that God has not (or could not have) spoken and the presupposition that he has (or could have) spoken are inextricably at odds with one another and thus fight for the same territory in defining the nature of all discourse.

Works Cited

An-Nabawiyah, Mushaf Al-Madinah, Trans. The Holy Qur-an: An English Translation of the Meanings and Commentary. Revised and Ed. by the Presidency of Islamic Researches, IFTA, Call and Guidance. King Fahd Holy Qur-an Printing Complex.

Aravamudan, Srivinas. “ ‘Being God’s Postman Is No Fun, Yaar.’ Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses.” Diacretics 19.2 (Summer 1989): 3-20.

Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Booker, M. Keith. “Beauty and the Beast: Dualism as Despotism in the Fiction of Salman Rushdie” ELH 57.4 (Winter 1990): 977-997.

Caneday, Ardel B. “Veiled Glory: God's Self-Revelation in Human Likeness—A Biblical Theology of God’s Anthropomorphic Self-Disclosure” in Beyond the Bounds: Open Theism and the Undermining of Biblical Christianity. Eds. Justin Taylor, John Piper, and Paul Helseth. Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2003. 149-199.

Finney, Brian. “Demonizing Discourse in Salman Rushdie’s ‘The Satanic Verses.’” ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature 29.3 (July 1998): 67-93.

Frame, John M. The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God. Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1987.

Francois, Pierre. “Philosophical Materialism in The Satanic Verses” in Reading Rushdie: Perspectives on the Fiction of Salman Rushdie. Ed. M. D. Fletcher. Atlanta: Rodopi, 1994.

The Holy Bible. New International Version. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1984.

Horton, Michael S. “Hellenistic or Hebrew? Open Theism and Reformed Theological Method” in Bey ond the Bounds: Open Theism and the Undermining of Biblical Christianity. Eds. Justin Taylor, John Piper, and Paul Helseth. Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2003. 201-234.

Maitland, Sara. “Blasphemy and Creativity” in The Salman Rushdie Controversy in Interreligious Perpective. Ed. Dan Cohn-Sherbok. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1990. 115-130.

Mann, Harveen S. “‘Being borne across’: Translation and Salman Rushdie’s ‘The Satanic Verses.’” Criticism 37.2 (Spring 1995): 281-309. Infotrac Onefile.

Rushdie, Salman. Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981-1991. London: Granta Books, 1991.

---. The Satanic Verses. New York: Viking, 1989.

---. Shame. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1983.

Sawhney, Simona. “Satanic Choices: Poetry and Prophecy in Rushdie’s Novel.” Twentieth Century Literature 45.3 (Fall 1999): 253-277.

Suleri, Sara. “Contraband Histories: Salman Rushdie and the Embodiment of Blasphemy.” Yale Review 78.4 (Summer 1989): 604-624.

Werbner, Pnina. “ Allegories of Sacred Imperfection: Magic, Hermeneutics, and Passion in The Satanic Verses.”Current Anthropology: A World Journal of the Human Sciences 37 supp (Feb 1996): 55-86.

Notes

[1] In some sense, it seems that the place once occupied by theology as the queen of the sciences, then superseded by philosophy during the Enlightenment, and the natural sciences in the modern age, has been taken up by literature in the postmodern age. [^]

[2] Throughout this essay, my references to “literature” and “satire” will draw heavily upon how I understand Rushdie to conceive such things. The nature of literature has been much disputed by the emergence of theory in the past thirty years. Due to time and space constraints, I will be unable to formulate a place for literature within a world view defined by divine revelation. In setting literature and revelation against one another, I do not intend, however, to be proscribing all literary works (or even all postmodern literary works) from religious engagement (nor to suggest that secular postmodern literature ought not write about religion). Rather, this essay simply seeks to grapple with Rushdie’s conception of literature and its engagement with religion. As for the role of literature within a theologically-grounded discourse, I would agree in measure with Sara Maitland, who writes concerning the Rushdie Affair, “In a sense all human creativity, and especially that using words which is what god is said to have used, must be seen in a real sense as a divine act, a tiny gesture of what it means to be ‘made in God’s image.’ The sad thing is not that people use this gift to say less than flattering things about the tradition out of which they came, but that they should use it without knowing their own divinity and their own likeness to God” (128). [^]

[3] Pierre Francois indicates a similar error (though he may avoid making it himself) in his essay “Philosophical Materialism in The Satanic Verses,” by absorbing the premises of Ludwig Feuerbach. He writes, “This much is already clear: Rushdie concurs with Ludwig Feuerbach’s contention that, far from being ‘an eternal, absolute, universally valid word,’ the ‘holy book’ (whether it be Feuerbach’s Bible or Rushdie’s Qur’an is indifferent to our argument) is actually ‘a historical book, necessarily conceived under all the conditions of temporality and finiteness.’” Central to Francois’ statement is the word “all.” A Christian view of revelation, as I construct it below at least, admits of the finitude, limits, and temporality of language. It is the subsequent inference that this invalidates the eternal validity of divine “word” that revelation-based religion denies. [^]

[4] My knowledge of Jewish tradition is much more cursory, however, I presume from the existence of the Greek Septuagint that, historically speaking, there has been some embracing of biblical translation. [^]

[5] Again, this paradigm is defined by my conception of a Christian perspective (as one representative of a supernatural hermeneutic) on the issue of scriptural inspiration, and thereby may exclude not only an Islamic understanding but also other Christian traditions. I have not, for instance, included the magisterium of the Catholic Church as a necessary step between the Bible and the people as Catholic theologians would. For two representatives of what I have described here, drawn largely from an evangelical Christian hermeneutic, see the articles of Michael Horton and Ardel Caneday in Beyond the Bounds. [^]

[6] As noted above, Gibreel acts as both the giver of the recitation (presumably in Arabic) and as recipient of the translation (in English) when he is in London. Hence, within the novel, as an English-reading archangel in London, Gibreel receives a “translated” text when he attempts to interpret his experience. [^]

[7] In Horton’s terms, Rushdie’s paradigm essentially denies the analogical connection between a divine source (outside of the hermeneutical circle) and the human understanding within that circle. Horton, for instance, denies that knowledge may be absolute – i.e. as God himself knows – but argues that this knowledge is communicable to humans in a way that they can understand. This sense of accurate yet non-exhaustive knowledge has been excluded by Rushdie’s paradigm. [^]

[8] In its context, Francois emphasizes the idealism of religion in opposition to Rushdie’s philosophical materialism. I disagree with his blanket construal of a religion’s idealism (which for him is a form of dualism), but nevertheless, I find his description of Rushdie’s position to be compelling. [^]

[9] I am hesitant to use this term, but for the moment it will serve its purposes. Horton draws a distinction between the terms univocal, equivocal, and analogical. He defines univocal as indicating that a term means the same things always. For instance, if one predicates that God is “good” and then uses it of human beings, the term “good” means the same in both cases. Equivocal, on the other hand, means that the same term may have totally different meanings in different context; to say a human is “good” and then use the same term of God sheds no light on the nature of God. Analogical, finally, means that there is some overlap between the use a term when it is used for God and when it is used for human beings, but dissimilarity also remains. Horton’s definition of “univocal” seems the most common use of the term, and he rightly argues that our understanding of God should be considered “analogical” (209-211). In the context of this paper, however, the word’s primary connotation is “exclusivity” or absoluteness.” Satire opposes the idea that any discourse can speak in an absolute or definitive way. In this sense, it opposes the supremacy of “one voice,” or the “univocal.” [^]