Reconstruction 7.1 (2007)

Return to Contents, Capital, Gender, Colonialism»

Punking Yoga: reconstructing post/neo/colonial fashion and movement / Tara Brabazon

Abstract: The branded clothes worn through sporting and fitness activities confirm that any movement, practice or behaviour that seems transgressive of heteronormative masculinity and femininity is also implicated in neo/colonial incorporations and the casualized workforce that is a characteristic of sports clothing manufacture. In an environment washed by the marketing of opposition, resistance is both difficult to define and apply in cultural studies. This paper invokes 'the problem' of resistance while denying the seamless and simple determinations of positive and negative representations. The focus of study is Yogurt Activewear, a company attacking corporatized yoga wear by creating an anti-brand brand. They advertise their products as a combination of yoga and punk. The calm corporeality of asanas has now been clothed with threat and confrontation. Yet the cost of this resistance and defiance - the price of building an anti-brand ‑ is a loss in the complexity of yoga's pre/post/colonial origins.

Stop. We greet you as liberators. This 'we' is that 'us' in the margins, that 'we' who inhabit marginal space that is not a site of domination but a place of resistance. Enter that space ... I am speaking from a place in the margins where I am different, where I see things differently (hooks 152).

bell hooks

<1> In the midst of post-fordism and cold modernity, it is unworkable to differentiate between centre and margin, sameness and difference, us and them, threat and compliance. The speed at which semiotic incorporation transforms radicalism into advertising has increased. In an environment washed by the marketing of opposition, not only is resistance difficult to define, but also to apply. In response to this political and intellectual challenge, Michael Erben discloses the value of embracing this ambivalence, confirming that, "it is not a problem that the lives we study and examine should remain ambiguous, mysterious, discordant and confused" (Erben 12). This paper acknowledges Erben's realization, invoking "the problem" of resistance while denying the seamless determinations of positive and negative representations. The goal is to research an object of culture that is intentionally "ambiguous, mysterious, discordant and confused". The focus of study for this special issue of Reconstruction is Yogurt Activewear, a company attacking corporatized yoga wear by creating an anti-brand brand. They advertise their products as a combination of yoga and punk. The calm corporeality of asanas has now been clothed with threat and confrontation. Yet the cost of this resistance and defiance - the price of building an anti-brand - is a loss in the complexity of yoga's pre/post/colonial origins. My investigation of the company commences with definitional discussions of resistance and follows with a presentation of the Yogurt Activewear "project". The final part aligns these two sections to demonstrate the costs and losses of this "punk" threat to corporatized yoga clothing, particularly in terms of social justice in a (post)colonial age.

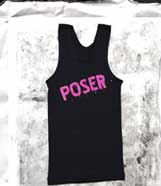

Resist this

<2> The branded clothes worn through sporting and fitness activities confirm that any movement, practice or behaviour that may appear transgressive of heteronormative masculinity and femininity is also implicated in neo/colonial incorporations and the casualized workforce that is a characteristic of sports clothing manufacture. While Becky Beal was able to locate concrete examples of "social resistance" (Beal 252) and "active consent" (Beal 253) in the "subcultural" sport of skateboarding, the study of yoga as a practice and Yogurt Activewear as a company does not reveal such stark and clear definitions or determinations. To construct a workable definition of resistance in this study of Yogurt Activewear that also contextualizes their 'punk meets yoga' slogan, we return to one of the most recognized monographs of cultural studies history: Dick Hebdige's Subculture: The Meaning of Style (1979).

<3> Subcultural theory, as constructed by Hebdige and associated with the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham University more generally from the late 1970s, has two elements. First, resistance to dominant codes and ideologies is present. Second, there is - through time - an incorporation of these resistances into the dominant discourse. Therefore the term subculture must be used with analytical care as it is both historically specific and socially dynamic. A subcultural semiotic system in one year becomes part of the dominant socio-cultural framework and market economy the next. Also, for cultural studies theorists specifically, when we deploy the word "subculture" it carries forward both the strengths and the weaknesses of Hebdige's arguments, particularly with regard to absences in the discussions of colonization and gender.

<4> The use of subculture as an analytical tool in cultural studies provides a constant theoretical reminder that there are larger units of societal organisation to consider such as class, and resistance is always possible no matter how conservative and repressive the environment. Yet with class politics and class consciousness being sidelined through the 1980s and 1990s, and rarely discussed in public discourse through the 2000s, there is an intricate discussion to be had - again - about the relationship between subcultural/symbolic politics, and real/parliamentary politics. Subcultural theory was effective in showing that politically inert periods, like the 1950s and early 1960s, encased nodes of political challenge. The Teds, Rockers and Mods shredded interpretations of the 1950s and early 1960s as being "quiet times" or "grey decades". Political challenge - through subcultural theory - was always present through "rituals" and disruptions to the social semiotic systems of clothing and music. The theoretical difficulty emerges when these groups and modes of challenge are overloaded with political consciousness. Groups like the punks, mods and rockers "represented" far more than they ever actually achieved socially or politically.

<5> Punk, even more than the mods and rockers, was a necessary "movement" and semiotic system for cultural studies theorists in establishing and performing the politics of the paradigm. Through the tight convergence of resistance, youth and punk, specific inflections and biases emerged from the history of the field. Harriot Beazley confirmed that the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies approach, "has also been accused of being too focused on white, male, working-class youth" (183). From this basis - and predisposition - gender and racial divisions were marginalized, but then re-emerged through such books as Women take issue (1978) and There ain't no black in the Union Jack (1987). When McRobbie published her "Settling Accounts with Subcultures" in a 1980 Screen Education, she emphasized an absence that, in retrospect, appears blatantly obvious. The "classic" sociological works conducted by Stan Cohen (1972) and Paul Willis (1977) not only emphasized spectacular subcultures to the detriment of "normal youth", but relegated women to the roles of mothers and girlfriends. McRobbie also highlighted the contradictions arising through a discussion of class and gender in relation to youth. Her feminist critique located the major weakness of the Birmingham "project". McRobbie was heavily influenced by the explosion of signs derived from punk, and she chose her time correctly: Willis, Cohen, Hebdige and others had, for too long, refused to ask the most preliminary feminist question: What about women? They rebuffed the exploration of youth beyond spectacular male behaviour in working class urban communities in England [1].

<6> Punk was a specific subculture. Yet the word has an ideological currency that transgresses Thatcher's Britain and the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Punk has moved beyond the Sex Pistols, Nirvana and Green Day. Morgwn Rimel, founder of Yogurt Activewear, states that "it may seem like they are at odds, but if you think about it, punk rock is more than just music and style. It's an aptitude - a way of life and being, just like yoga" (2006). Punk - like yoga - has followed the structural trajectory of subcultural theory, occupying a space of difference and then being emptied of resistive content to become part of dominant cultural frameworks. Both these trajectories of subculture - resistance and incorporation - are deployed by Yogurt Activewear.

Don't be active - be proactive

<7> Yogurt Active Culture is an Australian-based company formed in January 2006 by Morgwn Rimel and Gaylee Butler that describes its project as a fusion of punk and yoga. Manufacturing men and women's clothing along with yoga props, the company offers resistance - through clothing - to both the neo/colonial spirituality of the practice and the increasing commodification and branding of the shirts, pants, mats and bags. They have consciousness and intent in their use of punk resistance, with Morgwn Rimel being a graduate of a media and cultural studies degree. Through her knowledge, Hebdige not only returns to popular culture, but to fashion. Deploying an e-commerce portal - http://www.yogurtactiveculture.com - the company uses humour to prick the (mock) seriousness and pseudo spirituality of yoga. One of their shirts features the slogan 'Poser.'

The rationale for the word includes a quotation from Kurt Cobain, solidifying the rock and yoga connection. This statement from the former Nirvana lead singer is then followed by a justification of the 'poser' label through the yoga discourse.

Practicing yoga postures (asanas)

is to calm the mind

dissolve tensions of the ego

and put an end to the duality you perceive

between who you are and who you want to be.

STOP POSING. START PRACTICING ('Poser').

Such a statement notes that while popular cultural renderings of yoga focus on the asanas - the poses - actually it is the practice, the fluid movement between static postures without investment in the result, is the advanced goal.

<8> While affirming different layers and levels of connection between the corporeal and the cognitive, the ideology of rock cuts through this discussion via their black shirt, featuring the slogan "Rock hard core".

Build rock hard core strength.

In yoga, you can do this by pulling your chin, abdomen and pelvic floor upwards and inwards while you practice.

Jalandarabandha (chin lock)

Uddlyanabandha (abdominal lock)

Mulabandha (pelvic floor lock)Lock your core ('Rock hard core')

This alignment of the words "rock hard core" concurrently serves to mask the normalization of women's body shape. While making their products available in small, medium and large - without any sense of how that sizing standard is constructed - all the photographs feature thin and gently muscled women. While there may be resistance to the "hippy" components of yoga, there is little sign of change, critique or transformation of normative body shape for women [2].

<9> Clothes are the punctuation for the social grammar of identity. Through clothing, sexual differences are assumed, hidden and overlaid with social meanings. Via a study of a clothing company like Yogurt Activewear, this semiotic system can be discussed overtly, and clothing placed into its context of both reinforcing and threatening normative social values and exchanges. A.C. Sparkes realized that "certainly, much recent theorizing about the body has tended to be cerebral, esoteric, and ultimately a disembodied activity that has operated to distance us from the everyday embodied experiences of ordinary people" (17). Clothes are part of this distancing function, but also serve to reveal the visual literacies in operation through our lives. We learn expectations of women's bodies, shapes and coverings. Even when positioned in unconventional poses, as is common through the cycles of yoga poses where breathing patterns and normalized bodily movements are questioned, viewers learn about "natural" shapes and conventional definitions of beauty.

<10> The owners of Yogurt Activewear are also teachers who work in a studio run out of Sydney in Australia. The framing of their yoga practice is captured by the title of their enterprise: Body Maintenance Studio. While in the business of "Body Maintenance", yoga holds a specific position in sport and physical culture. While it requires strength, by necessitating the stacking of joints in asanas to permit the muscles to hold body weight, the overarching goal in the (physical) components of yoga is to increase flexibility and mobility. Positioned in a fitness studio as part of the group fitness or aerobic classes, yoga is disconnected from the masculine environment of the gym and does not use weights. There is space for women to move differently and to work on their bodies as an objective and objectified object, to maintain their corporeality as they would a car.

<11> In acknowledging how yoga can be inserted into conventional narratives of feminine slimness, beauty and vanity, Yogurt Activewear simultaneously deploys the bricolage and reinscription to rip through these expectations, as was a characteristic of punk resistance:

Don't be active - be proactive

Our clothes are comfy to practice and cool to live in.

Our designs communicate ideas we hope more people will think about ('Men's proactive-wear').

Particularly of significance, in terms of activating a punk threat, is the construction of a gritty urbanity around yoga. The portal into their e-commerce site features a wall with the graffiti-like inscription of their company name.

Instead of yoga's discursive alignment with nature, city-based graffiti art transforms the sign system. Shirts feature slogans including "Cobra" and "Enlighten me", which shows the icon of skull and crossbones. Such slogans are part of the punk challenge, to deploy bricolage so that familiar - and often disturbing - images can be repositioned into a new context to not only freshen up the discourse, but confront assumptions about the peacefulness of yoga.

The aggression of the clothing - the directive to the instructor and other participants to "Enlighten me" - is a perpetuation of punk's intimidatory semiotic system. The punk ideology amidst yoga practice also spills into the advertising of the "six-string mat":

Certain lights or sounds can stimulate emotional, mental, physical or spiritual responses in our bodies. Each of the 6 spinal charka centers corresponds to a particular colour and musical note. Regular adjustments of the charka centers helps keep our organs functioning properly. When they are balanced, your energy or life force flows freely.

STAY TUNED ('Empower tools')

The guitar featured on the mat displaces the colours, images and fabrics that align yoga with nature. Instead electric instruments and Western systems of musical notation are overlayed with discussions of life force and energy.

<12> The role and function of the "spirituality" or religion in yoga has been a node of recent controversy that will be explored in the final section of this paper. But Yogurt Active Culture confronts this issue directly with their "Convert" shirt:

The justification of the slogan includes an excerpt from the Bhagavad Gita: "if we aren't prepared to let go of yesterday's truths, we fall prey to the fundamentalism found in any of the major religions" (Gita). The interpretation of this statement from the company is to "Convert energy not people" ('Convert'). The use of words like "enlighten" and "convert" suggests action and agency. It is no surprise that Yogurt Active Culture advertises its range of props under the headline of "Empower Tools".

<13> Clothes transform bodily surfaces into texts to be read, signalling community allegiances or threats. Clothing is a complex semiotic system, particularly when entering the discourse of fashion. Signifiers are continually emptied and signifieds reconfigured. Yoga signifies "the east". Commodified branded yoga clothing signifies "the west". Yogurt Activeculture Wear is a punk formation moving between these categories, and offering uncomfortable alignments of neo/colonialism and anti/orientalism. Rimel states that she is "using western language to talk about an eastern philosophy within the context of their own pop cultural experience ... Yoga is thousands of years old and was punk before punk rock even existed" ('God save the Yogis'). This mixed (up) history cannot initiate or stop either resistance or uninhibited incorporation. The company works through ambiguity, aligning threat and humour. Through the confrontational comedy - Enlighten Me or Poser - there is an appreciation that challenge and change is part of yoga. It is not an ahistorical, depolitical and "natural" practice untempered by politics, the market economy or colonization.

<14> To capture this incorporation (with attitude), the clothes and products have been promoted in women's magazines and websites. Marilyn Perez, in Venuszine.com, states,

Some may cringe at the idea of 'Disco Yoga' or 'Punk Rock Yoga,' believing it defeats the purpose of relieving stress and finding peace within. With the popularity of Yoga in the West, along with yoga clothing lines such as Lululemon and Be Present taking off, it's become apparent that people want to look good while holding Vrksasana (Tree post). Sweatpants and a tee just won't do anymore. Its popularity is especially growing among younger people. Some practitioners are concerned that the true meaning of the practice will be dumbed down for the secular crowd. Thanks to yogis like Morgwn Rimel, founder of Yogurt Activeculture Wear, they are hoping their product will not only draw people to yoga, but also show that it is safe to spice up this ancient practice. Yogurt Activeculture is using western language to introduce an eastern philosophy (2006).

The trajectory and confusions of punking yoga with both subcultural and corporate infusions is revealed through this passage. The need to "look good" while holding Vrksasana and to "spice up" an "ancient practice" confirms the arguments made in the first two sections of this paper. In acknowledging that yoga is Sanskrit for "union", (literally) embodying a fusion of mind, body and spirit, there are racial and colonial applications that reveal the costs and consequences of suturing semiotic systems through punk bricolage.

Active Denial

<15> Yoga is now part of popular culture. It has become the cure for a range of "diseases" of consumption, whether it be an eating disorders [3] or stress management [4]. The "East" once more rescues and cures the "West". This is an orientalist discourse, with the "East" exoticised, romanticized and objectified. Such a reified relationship - of dominance and subordination - is made clearer when adding sportswear to the discourse. While yoga's "Eastern" ideologies have been appropriated and used in the "West" Indian workers have been the cheap labour that actually makes the clothes in which "their" asanas are performed.

<16> In 1992, the Vice President of Reebok Technical Services for the Far East recommended that India be the base for their operations, as an alternative to China (D'Mello 26-40). This decision was made after the Indian parliament made a decision in July 1991 to deregulate their economy, encouraging "free trade", privatization and the movement of international capital. The reduction in government guidelines was appended by a reduction in direct social welfare. India then became the base of operations for international subcontracting in sportswear. So while " India" is deployed in yoga discourse as a spiritual home and the origin of the asanas, the actual landmass of India is the basis of corporate power and profits, based on the manufacture of the clothes in which the postures take place. Bernard D'Mello realized the consequences of this gap between the "real" and "imagined" India:

India has a vast pool of surplus labor living in abject poverty. The wage rate at which India's poor are obliged to offer their labor services is so low that India can possibly emerge cost and price competitive in a whole range of relatively labor intensive manufactured goods ... From a social perspective, the cost and price competitiveness may not reflect the strength of the Indian economy but rather the weakness, because it is predicated upon the relative poverty of the Indian people (32).

This is the context in which any threatening bodies should be placed. While Yogurt Activewear stresses the "punk" element in their designs, they provide no information about fair trade practices, or how their garments and products are made. They certainly resist the pastel-infused Nike/Puma/Reebok yoga wear. Yet capitalism remains the default position: punk has become a brand and a strategy to differentiate yoga clothing in the branded market. Yoga has been incorporated into sport: yoga wear is part of sportswear. Despite its long history in India, yoga has not been spared from corporatization. In 1999, Christy Turlington "designed" a yoga range - titled Nuala - for Puma. In 2005, Stella McCartney released yoga clothes through Adidas. There are Gucci yoga mats and Hermes yoga bags. Yogurt Activewear is part of this history.

<17> The branding of yoga may seem to both corrupt and corrode the "authentic" history of the practice. Yet yoga is not a stable practice. Throughout its long history, it has changed and moved. As Sarah Strauss confirms,

To Indians, the type of yoga re-oriented by innovators like Vivekananda and Sivananda suggests empowerment, using an imaged shared history to create a progressive, self-possessed and unifying identity. In this light, yoga can be understood as part of a methodology for living a good life. Because of its basis in bodily practice, the yoga tradition is easily linked with physical health maintenance at the level of the person. The physical development of the person was seen by many as the first, necessary step to be taken in the service of improving a larger community, whether local, national, or global. Yoga re-oriented this new theory with old practice (248).

Strauss offers the important argument that physical and cultural movements like yoga are dynamic and changeable. To deny such change is not only an actualization of neocolonialism but an imposition of neo-primitivism. In such a discourse, the practices of the colonized are stable but colonizers are infused with ideologies of progress. The key recognition is what is lost and gained through the movement of yoga out of India. Significantly, the rights of textile workers in India are disconnected from the practice and ideology of summoning a spiritual India in the midst of a yoga class.

<18> Quite impressively, this ownership, proliferation and popularity of yoga are discussed by practitioners. In the magazine Australian Yoga Life for March to July 2006, a long article was published under the title "Who owns yoga?" (6-10), Greg Wythes confirms that,

Yoga is now a practice that straddles both its Indian birthplace and the broader Western world. However, there seems to be mounting evidence that there are growing tensions in this process of adoption and change from the traditional culture of yoga's beginnings to the contemporary culture of today's capitalist society (7)

Wythes acknowledges that yoga is a business. He also notes that Indian-based practitioners are losing ownership of practices and sequences. By 2005, the United States patent office had granted 134 yoga-related patents on "accessories", 150 yoga-based copyrights and 2315 yoga trademarks (7). To make the question of ownership of cultural ideas even more intricate, many of these copyrights, brands and patents were granted to expatriate Indians. Recognizing what is being lost to India through "Western" creative industries management, the Indian government has assembled a taskforce with the goal of creating a database of yoga practices to protect Indian knowledge systems.

<19> In February 2003, Bikram Choudhury copyrighted a sequence of 26 poses, and the verbal directions used to teach the sequence. He also threatened to defend these rights through litigation. By 2004, Choudhury himself became enmeshed in litigation. Yoga practitioner and teachers - under the title of OSYO (Open Source Yoga Unity) challenged his "ownership" of the sequence. They argued that the poses were hundreds of years old and therefore in the public domain. Unfortunately this case was settled out of court, which meant that the legal status and copyright over yoga postures still remains debateable. Wythes confirmed that this case captures the challenges - politically and economically - of yoga's immersion in popular culture:

This case highlights the broader concerns about the way yoga is being commercialised in the West. OSYU initially challenged Bikram along ideological lines, espousing the view that their concern was for the rights of the yoga community at large. But when they were able to come to an arrangement that suited their own purposes, i.e. to be free to teach and practice without legal threat form Bikram, they accepted a settlement (7).

Once more, resistance is difficult to track and determine, as practitioners and teachers become implicated in intricate power struggles. Such moments of commercialization and vested interests are particularly troubling to the yoga discourse as modalities of spirituality, higher powers and a divestment in the self are part of the paradigm. This issue was raised effectively by Kausthub Desikachar, son of TKV Desikachar and grandson of T Krishnamacharya.

Yoga was created for the purpose of nourishing a spiritually oriented life. However, we are living in a capitalist oriented world, and therefore, I think we must use yoga to help us find balance. Yogis have to work and earn an income to pay for their own food, shelter, education, and clothing, as well as support a family. However a $100 yoga mat wrapped in a $200 yoga tote bag that is slung over a $300 yoga top is not the way to go either. I think finding a balance between the material and spiritual world is the key today. And it is definitely not easy (in Wythes 7).

This statement is probably the clearest and most accurate way to assess yoga in the contemporary environment. Yogurt Activewear is resisting the corporate branding of clothing. Yet - with self aware irony - they are enacting this process through appropriating the codes and signs of earlier modes of resistance, such as punk. So threatening "punked" yoga wear has become a marketing strategy, not a political imperative.

<20> When cultural practices move from formerly colonized nations, there must be attention to how the complexity of ideas is either maintained or lost. Suzanne Hasselle-Newcombe confirms that,

Given the mixed religious and philosophical background of yoga practice in the Indian context, one cannot make many assumptions about the beliefs of yoga practitioners in the modern British context. When the British practice yoga, is it simply for health benefits or is it a meaningful spiritual activity? ... To what extent do yoga practitioners adopt Indian religious worldviews? Could yoga be a new form of religion for a pluralistic, secular culture (306).

Iyengar yoga places attention on the sequence of postures. "Religious" or "spiritual" attributes or characteristics are less associated with this practice. The reason for this separation of body and mind emerged when B.K.S. Iyengar visited Britain in 1954 and worked with Peter Mackintosh, the chief inspector of Physical Education in the Inner London Education authority, to design a yoga curriculum. It was a condition of those classes that they were "physical" and not "religious".

<21> Through such curricula strategies, yoga becomes equivalent to other fitness practices, erasing much of its history. This transformation has occurred in the era where "creating a brand appears to mean more to sports marketing executives than any real connection the fans have to their teams" (Bishop 37). With yoga devolved of history, origin and context, the empty signifier can be filled with the corporate branding that frames the rest of sports media. Branding is now organizing social identity, devoid of the complex and contradictory history of India. Vincent Carducci confirmed the consequences of removing history, politics and struggle from sports media, to be replaced by a brand:

Nike epitomizes the postmodern 'hollow' corporation. The company owns little by way of fixed assets, focusing instead on managing its cultural capital and maximizing its financial strategies ... From a postmodern perspectives, it can be said that Nike owns the surface effects while leaving the risk of investment in fixed assets to others (43-44).

The focus on surfaces is ideologically against the imperatives of yoga, which actively de-emphasizes externality. Morgwn Rimel tries to reconcile these variables through her clothes and company, providing a rationale for her fashion/yoga project: "We hope to develop an Activeculture that's NOT just about yoga, but that broadly promotes truth and beauty, encourages playfulness, cultivates individual style and wellbeing, and most importantly, inspires us to make positive changes in our lives and the lives of others" (in Perez). With this goal in mind, Rimel articulates her target market for the clothes: "25-40 age group where yoga is part of your life and you're not a hippy and not a mum ... Yoga's not always relaxing ... It can be quite confronting and intense and we wanted to express that mental and emotional side" (in Lunn). There is no mention of yoga's history, or the goal of aligning mind, body and spirit. Instead, this new brand has created an anti-brand that excludes "hippies" and "mothers". This difference becomes the basis of a resistance, but the target of the resistance is unclear. Even Slimming & Health Magazine entered the yoga/punk discourse by outlining the company's goal: "Created as an alternative to the boring pastel and conservative range of clothing currently out there, this kooky range of T-shirts and pants will put a smile on the face of your fellow posers" ('Pose off'). Humour and difference render yoga clothes one more consumer project that creates pleasure through the purchase.

22> Threat and challenge are difficult to define and even more complex to locate in a commodified post-work age of lifestyle, brands and logos. Therefore, while Yogurt Activewear is not Nike, it still captures an investment in a brand. It is part of what Clive Hamilton and Richard Denniss describe as Affluenza where "we are confused about what it takes to live a worthwhile life" (7). The buying and selling of identity creates desiring selves that must constantly manage disappointment. Consumerism becomes the metaphoric stitching to align the ideal and actual selves. Yet while consumerism creates an investment in surfaces, there is a parallel desire for authenticity. Richard Butsch argues that "the future of leisure studies and cultural studies lies weaving together the threads of domination, resistance, and incorporation in order to understand leisure and popular culture in an era of hyper commodification and consumption" (78). Yogurt Activewear is positioned in this space between commodification and authenticity,. It is clothing to brand resistance within capitalism, and the fashion choice of threatening bodies posing through (post)colonialism.

Reference List

Beal, B. 1995. Disqualifying the official: an exploration of social resistance through the subculture of skateboarding. Sociology of sport journal. 12(3). 252-267.

Beazley, H. 2003. Voices form the margins: street children's subcultures in Indonesia. Children's Geographies. 1(2). 181-200

Bishop, R. 2002. Stealing the signs: a semiotic analysis of the changing nature of professional sports logos. Social Semiotics. 11(1). 23-41.

Boudette, R. 2006. How can the practice of yoga be helpful in recovery from an eating disorder? Eating disorders. 14. 167-170.

Butsch, R. 2001. Considering resistance and incorporation. Leisure Sciences. 23. 71-79.

Carducci, V. 2003. The aura of the brand. Radical society. 30(3-4). 39-50.

Cohen, S. 1972. Folk Devils and Moral Panics. London: MacGibbon.

Convert. 2006. URL: http://www.Yogurtactiveculture.com/mens/mens.htm.

D'Mello, B. 2003. February. Reebok and the global footwear sweatshop. Monthly Review. 26-40.

Empower tools. 2006. URL: http://www.Yogurtactiveculture.com/tools/images/Wmpower_tools_text.jpg.

Enlighten me. 2006. URL: http://www.Yogurtactiveculture.com/mens/mens.htm.

Erben, M. 1998. Biography and Education: a reader. London: Falmer.

Gilroy , P. 1987. There ain't no black in The Union Jack. London: Hutchinson.

God save the yogi, it's anarchy in the ashram. 2005 December. National Post. URL: http://Yogurtactiveculture.blogspot.com/.

Granath, J. Ingvarsson, S. von Thiele, U. Lundberg, U. 2006. Stress management: a randomized study of cognitive behavioural therapy and yoga. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 35(1). 3-10.

Hamilton, C. and Denniss, R. 2005. Affluenza. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin.

Hasselle-Newcombe, S. 2005. Spirituality and 'mystical religion' in contemporary society: a case study of British Practitioners of the Iyengar Method of yoga. Journal of contemporary religion. 20(3). 306-318.

Hebdige, D. 1987. Subculture: The meaning of style. London: Routledge.

hooks, b. 1990. Yearning: race, gender, and cultural politics. Boston: South End Press.

Leadbeater, C. 2000. Living on thin air: the new economy. London: Penguin.

Lunn, J. 2006 April. Downward dog adopts a rebellious pose. The Sydney Morning Herald. URL: http://Yogurtactiveculture.blogspot.com/

Martin, G. 2002. Conceptualizing cultural politics in subcultural and social movement studies. Social Movement Studies, 1(1). 73-88

McRobbie, A. 1980. Settling Accounts with Subculture. Screen Education. 34. 37-49.

Men's Proactive-Wear. 2006. URL: http://www.Yogurtactiveculture.com/mens/mens.htm.

Perez, M. 2006 May. Hardcore Asana Gear. Venuszine.com. URL: http://Yogurtactiveculture.blogspot.com/

Pose off. 2005 April. Slimming & Health. URL: http://Yogurtactiveculture.blogspot.com/

Poser. 2006. URL: http://www.Yogurtactiveculture.com/womens/womens.htm

Rimel, M. 2006 February. Yoga gets punky. Sunday Telegraph Newspaper. URL: http://Yogurtactivecultre.blogspot.com/

Rock hard core. 2006. URL: http://www.Yogurtactiveculture.com/womens/womens.htm.

Sparkes, A. 1999. Exploring body narratives. Sport, Education and Society. 4(1). 17-30

Strauss, S. 2002. Adapt, adjust, accommodate: the production of yoga in a transnational world. History and Anthropology. 13(3). 231-251

The six-stringed mat. 2006. URL: http://www.Yogurtactiveculture.com/tools/tools.htm.

Willis, P. 1977. Learning to labour. Farnborough: Saxon House.

Women's Studies Group. 1978. Women take issue: aspects of women's subordination. London: Hutchinson in association with the CCCS.

Wythes, G. 2006 March-July. Who owns yoga? Australian yoga life. 14. 6-10

My thanks are expressed to Morgwn Rimel of Yogurt Activewear for information about the company. However the interpretations and comments made in this piece are my own and are not representative of Yogurt Activewear.

Notes

[1] While McRobbie's critique was timely, there is no doubt that the nature of her commentary shut down analytical space surrounding youth. It must have been extremely difficult for men educated in the subcultural paradigm to follow through with their work in the light of McRobbie's comments. The date of McRobbie's article in Screen Education (1980) in many ways signalled a death of the study of youth subcultures. Certain 'taken for granted' categories and interests could no longer be justified. [^]

[2] In this way, Yogurt Activewear is perpetuating many of the standards and values of the fashion industry. Jan Wright stated that "the dominance of particular sets of values and beliefs over others is maintained through the practices of individuals and groups. For instance, media images, the fashion industry, aerobics instructors, physical educators who constantly promote thin bodies as the ideal for women provide messages about valued expressions of femininity," from 'Changing gendered practices in physical education: working with teachers,' (184) [^]

[3] Robin Boudette confirmed that - for her patients - yoga had been a successful 'medication.' She stated that "Yoga ... enables patients to experience their bodies in a new way. Living in a society that values how you look more than how you feel, eating disorder patients often relate to the body as an ornament; they suffer from a disconnection from the body, feelings, appetites, and inner experience," (168) [^]

[4] Jens Granath, Sara Ingvarsson, Ulrica von Thiele and Ulf Lundberg stated that "stress-related health problems, such as chronic fatigue, muscular pain and burnout, have increased dramatically in modern societies in recent years ... Yoga is an ancient Indian practice focusing on breathing and physical exercises, thereby combining muscle relaxation, meditation and physical workout," (3) [^]

Return to Top»