Reconstruction 9.1 (2009)

Avoiding the Peep Show: Talking from within the Tattoo Community / Rhonda R. Dass

Abstract: Within the tattoo community in the United States, and specifically within the tattoo artist community, the historic legacy of the commodification of tattooed individuals has created a strong reaction against the idea that they influence people in choosing to be tattooed. The narratives of capture and forced tattooing vilified the people doing the tattooing not those receiving the tattoos. While the carnival barkers were not identifying American citizens as the "barbarians" that would inflict ink on an unwilling person, the association nonetheless came to be. To distance themselves from the image of the "savage tattooer", the tattoo artist community has adopted an adamant stance concerning their coercion in the individual's choice to be tattooed. My role as both researcher and tattooist places me in a position where I must choose to break with one tradition to serve the other. This article examines the forces that created the current standing of communications both in the tattoo community and in the academic community that examines the tattoo community to better understand my changing role in my research and the barriers to communication that I have encountered over the course of my fieldwork. Examining the historic underpinnings, the available literature on tattooing, and my personal encounters in the field provide a foundation for this article and my research.

<1>"Step right up. Don't be shy, because you will not believe your eyes! [1]" The appeal of the forbidden, the exotic and different has been promoted, exploited and exaggerated in our culture to make money. Our American cultural practices and worldview greatly influence how we turn the human body into a commodity and how that commodity is then spoken of [2]. This is a major consideration when speaking of tattoos, an art form that is currently discussed as either a cultural practice or an aesthetic object.

<2> When I began my doctoral research, I had been a practicing member of the tattooist community longer than I had been in higher education. My dual role as tattooist and academic was the reason that I was drawn to investigate the use of tattoos for marks of identity and also to examine how those marks are translated over cultural boundaries. I know the field from a very unique perspective and felt more than prepared to speak for my community. Problems arose as soon as I began to form my research proposal. To speak from within the tattoo community I had to examine my role – both that of tattooist and academic. Through this examination, I found a number of reasons why I was having a hard time talking from within the tattoo community. To avoid the peep show that usually accompanies a discussion of tattoos and the tattoo community, I needed to find a way to translate across the tattooist/academic boundaries. As I strive to complete this translation and complete the write-up of my dissertation research, I know we also need to look at why this translation is necessary in the first place.

<3> There is a clear division in the literature that is available when discussing tattooing. The academic literature gives a cultural perspective of the practice of tattooing that examines the art form in the context of specific culture groups and its social ramifications. The authors of these works are usually individuals who have been pulled to the tattoo community through their research and become tattooed individuals or tattooists as a step in their academic growth [3]. Some, such as Makiko Kuwahara [4], remain unmarked and approach the study of tattooing from a clearly outsider stance. The tattoo community produced literature is clearly from an insider perspective. While many of these works are in the form of photographic arrays for aesthetic appreciation, some contain insightful analysis of the practices such as the works of Don Ed Hardy. One notable exception in this division is the book Bad Boys, Tough Tattoos by Samuel M. Steward, PhD. Dr. Steward was a disaffected academic who began researching tattooing once he was a practicing tattooist at the impetus of Dr. Kinsey, a former colleague, who asked him to help in his collection of data. Dr. Steward collected information on clients' sexual reactions to tattooing for Dr. Kinsey [5]. Steward's book brings us a cultural based look at the tattoo community of Chicago during the restrictive era sandwiched between the heyday of tattooing on the circus circuit and the American Tattoo Renaissance. Aside from Dr. Steward's book we hear few tattooist voices speak out on the cultural role of tattooing.

<4> Why do we hear so few voices, the actual authorities, from within the tattooist community? The popularity of reality television shows on tattooing would make it seem that it is a topic that the American public is open and receptive to. Who better to relate the cultural understanding of this aesthetic practice than those who work at it on a daily basis and have connections within the publishing industry [6]? What do the tattoo artists say [7]?

<5> The history of tattooing and the social reaction and marketing of tattooing to the American public must be examined to understand the current state of the dichotomous relationship within the literature on tattooing. The division of literary sources has noticeably made an influence on how we speak about tattooing [8]. I argue that there are more deeply imbedded reasons to the lack of communication.

<6> To make this article into a manageable size, I will look specifically at tattooing in the United States. Regardless of historic regional development of tattooing traditions and aesthetic understandings, the globalization of American ideologies through economic colonialism places the American perspective in a dominant position for the current development of tattooing internationally.

<7> The commercial aspects of tattooing have strongly influenced the way we talk about tattooing both inside and outside the tattoo community. By employing the medium of the human body, tattooing places itself in a precarious position that is not easily changed in regards to the legitimizing agency of the art world [9]. The liminal position of tattoo between cultural practice and object for aesthetic appreciation creates a divide in not only our understanding of tattooing practices but also the language we employ when speaking of tattooing. This positioning has allowed tattoos to stay outside of a clear aesthetic understanding that would restrict our vocabulary to a romanticized setting of artistic considerations. We do not speak of "starving tattooists" who "suffer" for their art, but rather our vocabulary shifts to discussions of process and performance where the issues of ownership of a creation are not breached [10]. Our consumer culture dictates a shift to the commercial aspects of the tattoo process. The value of a tattoo is not tied to the resale or investment value for the owner of a tattoo, but rather in the social understanding of the cultural practice and the value the individual perceives in acquiring the tattoo.  This valuation calls for an understanding of the commercial underpinnings of the tattooist community and the historic construction for the language utilized in the current manifestation of the tattoo world. My research brought me first to the history of the economics of tattooing in the United States.

This valuation calls for an understanding of the commercial underpinnings of the tattooist community and the historic construction for the language utilized in the current manifestation of the tattoo world. My research brought me first to the history of the economics of tattooing in the United States.

<8> Although the natives of America were tattooing long before the European settlers hit the eastern shore of what would become the United States, tattooing is commonly seen as originating with sailing traditions and in particular the voyages of Captain Cook to the South Seas islands [11]. This maritime tradition brought what was perceived to be an exotic practice to the attention of the aristocracy in the colonies and Europe. When it was seen that a person could make a living through the exhibition of tattooed flesh, living or dead [12], the number of individuals who availed themselves of this economic opportunity greatly increased, along with the number of individuals who would acquire tattoos for the sole purpose of exhibiting themselves for monetary gain.

<9> The tattoo exhibition tradition played well within the circus environment that developed in the later half of the 19th century. Tucked among the sideshow exhibits, the tattooed people of this time were seen as exotic and "other" like their companions who were physically abnormal or made to appear so by contrast. As economic times became harder during the late years of the 19th century and into the early days of the 20th century and the paying public became less easily impressed with tattooed exhibits, the narratives of how these colorful entertainers acquired their "otherness" became the drawing card more so than the skin itself. These narratives often told of captivity usually following a horrible storm and shipwreck, where the individual was forcibly tattooed. Once tattooed, the person was allowed to become part of the tribal group and married the chief's daughter. This type of narrative brought the tattooed individual out of what was seen as social deviance and allowed him to join the ranks of the unfortunate that has suffered due to his "physical deformities" [13].

<10> The historical development of these narratives in the commodification of tattooed individuals has led to two very distinct features within the tattoo world. One feature is the defensive posture of the tattoo artists when talking about client interactions. The other feature is how the tattoo community presents itself to both esoteric and exoteric groups in public presentations such as conventions and festivals. Both strongly influence the work of ethnographers and the underlying historic constructs must be taken into consideration when working with the tattoo community. Both features had presented themselves in my past research and would play a large role in my dissertation research as well. From my perspective from within the tattoo community I will explain how.

<11> Outside the tattoo community, those with tattoos are often still seen within this "freak show" context. They are the object of other peoples' interest and examination, sometimes being touched physically in ways that seem mostly inappropriate for normal circumstances. It is common for a tattooed person to adjust and even take off clothing in order to expose inked flesh. It is also not unusual for the person viewing the tattooed flesh to touch the exposed skin where social conventions would normally dictate distance in our usual American circumstances.

It is also not unusual for the person viewing the tattooed flesh to touch the exposed skin where social conventions would normally dictate distance in our usual American circumstances.

<12> Within the tattoo community, and specifically within the tattoo artist community, the historic legacy of the commodification of tattooed individuals has created a strong reaction against the idea that they influence people in choosing to be tattooed. The narratives of capture and forced tattooing vilified the people doing the tattooing not those receiving the tattoos. While the carnival barkers were not identifying American citizens as the "barbarians" that would inflict ink on an unwilling person, the association nonetheless came to be. To distance themselves from the image of the "savage tattooer", the tattoo artist community has adopted an adamant stance concerning their coercion in the individual's choice to be tattooed. The placement and design choice are areas where artists will admit that they try to "help" their clients, with some artists even refusing to do tattoos in certain places, such as the hands, face and genitalia, and some who refuse to do certain designs that they consider to be in bad taste. My research shows that tattooists while denying coercion will admit to guiding clients.

<13> My research among female tattoo artists focusing on the displays of identity reinforces this public stance on the influence tattooists have upon their clients. This stance may be why the women I spoke with were so adamant about the effect of their own tattoos on their clients. From the outlook of one female artist, who is appalled by the idea of influencing her clients to the outright rejection of the idea by another female artist, all reinforced the position of the tattooist's innocence in the decisions of someone to get tattooed. Contrary to their stated opinion, I saw a definite influence of the artist on the client. Through their conscious or unconscious efforts, tattooists have an effect on the choices of their clients, whether it concerns placement or design, and leave their distinct signature on the flesh of others. A tattoo's creator can sometimes be as easily identified as the painter of work on canvas. Tattooists become known for the style they work in as well as the technical application process that is evident in the finished work. It is manifestly visible in a custom work for an individual client. It is also evident in, what most consider the equivalent of mass produced art, "flash". Another artist may apply a piece of flash from the pages of one artist, and yet the design will still speak of the first artist and her identity and role in the finished tattoo.

<14> I found that the actual tattoos the artists chose to have on their own bodies also influence their clients. Being seen as an authority figure, their displays of body art set a standard within the community that is often mimicked by others in the quest for subcultural capital [14].

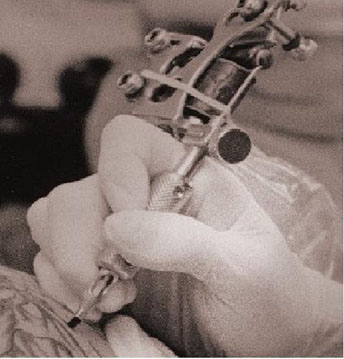

<15>This influence prompts us to look more closely at the tattoo interaction and at the agents within the performance of tattooing. While each of the artists wants to be seen as not influencing her clients in any way, the tattoo process is a collaborative effort that necessitates influence in its quest for legitimacy in American culture. Through the professional persona, the tattooist is seen as having the technical expertise to direct the process [15]. The physical production of the tattoo requires both the client and the artist to perform their individual roles that are not finished until the healing process is complete. The question of who is the artist is complicated. The tattooist contributes to the process through the application process, but how the client cares for the tattoo during the healing process will bear on the finished product. If the design is from a flash sheet or the drawing of another person, the question of who is the artist is further complicated. This collaboration may be key to the standing of tattooing within the art community. While the American ideal for art has expanded to include cooperative projects, it still defines art partially through the individual artist or creator. Because the canvas that the tattooist is working on is human flesh, issues of ownership come into the picture as well.

Through the professional persona, the tattooist is seen as having the technical expertise to direct the process [15]. The physical production of the tattoo requires both the client and the artist to perform their individual roles that are not finished until the healing process is complete. The question of who is the artist is complicated. The tattooist contributes to the process through the application process, but how the client cares for the tattoo during the healing process will bear on the finished product. If the design is from a flash sheet or the drawing of another person, the question of who is the artist is further complicated. This collaboration may be key to the standing of tattooing within the art community. While the American ideal for art has expanded to include cooperative projects, it still defines art partially through the individual artist or creator. Because the canvas that the tattooist is working on is human flesh, issues of ownership come into the picture as well.

<16>I had a friend and client tell me that soon I would be signing my tattoos due to my increased proficiency and fame. It was very abhorrent to me to think of putting my signature upon another person's body. I consider it a mark of ownership to put my signature or name to a work that I have created. By putting a signature to a tattoo, claims are assumed to the person as well as to the art. This idea of ownership of work must be extended to the person on who the work is done. As a tattooist, I had to keep my distance from this assumption of ownership-– a direct contradiction to that of my role as academic. An artist may influence a client but they may not force the client into anything. The client is still seen as having agency within the process. Our American ideas of property rights and intellectual property must be further explored to consider this area of collaborative art [16]. Tattooing must place itself outside the norm when talking about property rights.

<17>The circus narratives as well as the discourse surrounding the tattoo community that became prevalent after what is known as the "American Tattoo Renaissance" in the 1970s both influence the second distinguishing feature of the tattoo community of public presentation of tattooists as a group rather than individuals. When the practice of tattooing was banned due to a hepatitis outbreak following World War II, tattooists went underground and became closely associated with deviant sub-cultures in the United States. Tattooing was employed as symbolic resistance against mainstream American culture during the political movements of the 60s and lead to a gradual resurgence and acceptance of the practice in American culture of the later 20th century. During this time, various groups worked for the legitimization and legalization of tattooing. One avenue of legitimization was the tattoo convention promoting the idea of tattooing as a craft or trade.

<18>David Yurkew is considered the founder of the "tattoo convention" presentation style in the United States. In 1974, Yurkew organized the first tattoo convention as a venue and vehicle for tattooists to gather in community to share ideas and promote tattooing to the general public. Billed as the "International Tattoo Convention" it utilized the space and structure of a commercial trade show [17]. While his convention was not long lived, Yurkew did set precedence for the conventions that would follow. These conventions are the public face of tattooing in the United States today.

<19>In general, tattoo conventions are held in convention spaces utilized by other commercial entities, such as hotels and large convention sites in major cities. The space is divided into booth space where tattooists and other vendors sell their goods or services to the public. Educational seminars and live entertainment are often added to provide a draw for artists and the public. As with other commercial conventions, the organizers of the tattoo convention dictate what is permissible on the convention floor. Organizers regulate activities on the floor of their convention through a set of prescribed rules of acceptable conduct that prevent attendees from offending a middle-class sense of decorum. Standards of professionalism are promoted through these regulations and present a public image that helps to distance tattooing from its previous standing as a deviant activity. By restricting the locations of where tattoos are applied in this public arena, organizers reinforce the social standards that depict publicly placed tattoos, such as those on the hands and face, and tattooing of the genitalia as "deviant" or outside of mainstream sensibilities. These conventions set guidelines that influence tattooists both at the conventions and also in their home environments of the tattoo shop or parlor. The tattoo artist functions within the standards promoted by the tattoo conventions to ensure a basic economic stability.

<20>As a tattooist, the majority of questions I get, after those inquiring about the pain factor involved in the process, have to do directly with the economic factor. Even a recent guide on how to get a tattoo is mostly dedicated to price and how to negotiate a better deal. The commercial presentation of tattooing in the convention setting has clearly had an effect. Is this perhaps why there are not alternative forms of presentation being utilized for tattooing? My research has revealed few alternative forms of presentation.

<21>In September of 2003, Bruce Bart and Curse Mackey organized and presented the Woodstock Tattoo and Body Art Festival [18]. Their endeavor lasted only two years and is yet to be repeated in other areas. While the commercial aspects of the tattoo convention were present in the Festival, other areas of legitimization in the art world were presented as well. These included art gallery and museum exhibitions, and a distinct historical connection through the inclusion of the art colony of Woodstock, New York, and academic discourse through the forum of lectures and tattoo centered movies presented at the local theatre. Although the aim of the Woodstock Tattoo and Body Art Festival was in the words of co-producer Curse Mackey "Basically... to create a festival that revolved around tattooing." The underlying focus was to connect tattooing more in the aesthetic realm than in the commercial. "Tattooing is a connecting thread between other forms of popular art; paintings, sculpture, literature, and music [19]." By emphasizing the aesthetic rather than the cultural, the commercial aspects of tattooing were minimized in the presentation and, as a number of artists I spoke with at the festival noted, people attended the festival more to appreciate the art rather than to purchase a tattoo.

<22>Mr. Mackey and Mr. Bart have fallen silent after their second attempt to change the status of tattooing from craft to art. The female tattooists I spoke with for my research remain distanced from their influence and involvement. And while more academic books are being published each year on the cultural aspects of tattooing and aesthetic books continue to surface from tattooist writers, the world still stands divided. And my endeavors to conduct research within my own community remain complicated.

<23>Basically, a narrative has silenced tattooists. Through the promotional efforts of the commercial enterprise of tattooing, the narratives of the circus era of American tattooing have created a problem for those within the community. While this performance venue provided an avenue for survival of the cultural practice in a time of repressive social forces that could have ended tattooing in the United States, the promotional narratives put the tattooist outside of acceptable culture. Aligning oneself with the tattooist community, in effect, was to align not only with the "freak" community, but also, even more detrimentally, with those who forcibly created freaks. To regain acceptance and legitimization within the art community, the barrier of deviant association had to be not only broken down but also distanced to allow the tattooists to practice their craft.

<24>The tattooist narrative follows an aesthetic thread. By focusing on the aesthetic and discussions of line and style considerations, the tattooist avoids the implications of a cultural connection in the tattoo process. This avoidance of the cultural underpinnings of tattooing, allow the tattooist to distance their performance from the ideology prevalent during the circus era and following years of deviant classification in American society.

<25>To speak from within the tattoo community with authority on the cultural practice of tattooing is to break the code of silence that has prevailed through the 20th century revival of the art form. Will tattooing lower it's standing through the narratives of the tattooists who speak out? Not likely. The popular show, Miami Ink, is centered on the narratives of the artists as well as the clientele of a busy South Beach tattoo establishment. Through these narratives, the artists provide a more in-depth understanding of the tattoo process that is commonly lacking in the literature produced from within the tattoo community [20]. While this would appear to violate the code of silence, the tattooists are insulated from the community restriction by the mediating lens of a full production crew. They are in effect not the ones with the authority, but rather utilizing the authority of the documentary venue. The tattooist's agency is relinquished to the production staff.

<26>The academic community has the opportunity to also be a mediating lens for the tattoo community. Through the academic shift to an emphasis on ethnography that reveals the voices of those who are at the heart of our studies, we begin to get a clearer view through the perspective of the insiders. This insider perspective is reinforced through the authority that the academic lens provides. To effectively produce ethnography of the tattoo community, the historic constructs that shape current discourse from within the tattoo community must be taken into consideration. While the shift is, in my opinion, heading us in the right direction to speak more comprehensively about tattooing than in the past, we must be mindful of the underlying narratives that have shaped the language of the tattoo community as a whole. My dual roles can be seen as a benefit rather than a restriction when taken in light of this discourse. If I can bridge my role as tattooist to translate the traditions of tattooing through a cultural consideration, I can begin to show a hybrid understanding of tattooing that speaks in both worlds.

<27>Throughout this article and my research in tattooing traditions, I have struggled with my own roles as both tattooist and academic. Allowing myself to fully explore the cultural foundations of how a tattooist speaks of their art in today's world requires me to shift my allegiance to the academic community that is only a small part of my authority when broaching this subject. Allowing the tattooist to speak out on his or her understanding of the cultural practice requires mediation through an authoritative filter. For me to break the silence, I must break with the role as tattooist, and only allow those outside the community a mediated view of my "other" world. To avoid the peep show feeling this view supports requires a new vocabulary that will incorporate the cultural and aesthetic language to expand our understanding and provide a translation guide for my own research and hopefully for others after me.

Works Cited

Bogdan, Robert. 1988. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brain, Robert. 1979. The Decorated Body. New York: Harper and Row.

Camphausen, Rufus C. 1997. Return of the Tribal: A Celebration of Body

Adornment. Rochester, Vermont: Park Street Press.

Caplan, Jane, ed. 2000. Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Chinchilla, Madame. 1997. Stewed, Screwed, and Tattooed, Mendocino, CA: Isadora Press.

Chinchilla, Madame. 2003. Electric Tattooing by Women: 1900 – 2003. Mendocino, CA: Isadora Press.

Dass, Rhonda. Forthcoming. "Negotiating Tattoo Into Art."

DeMello, Margo. 2000. Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

DeMello, Margo. 1995. "The Carnivalesque Body: Women and Tattoos," in Pierced Hearts and True Love: A Century of Drawings for Tattoos. New York: The Drawing Center.

Durfee, Dale. 2000. Tattoo: Photographs by Dale Durfee. New York, NY: St Martin's Griffin Press.

Dye, Ira. "Tattos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818" in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.

Ferguson, Henry and Procter, Lynn. 1998. The Art of the Tattoo. London:Courage Books.

Gilbert, Steve. 2000. A Source Book: Tattoo History. New York, NY:Juno Books.

Gilbert, Steve. 1995. "Totally Tattooed: The Self-Made Freaks of the Circus and Sideshow" in Freaks, Geeks and Strange Girls: Sideshow Banners of the Great American Midway. Johnson, Randy et al. Eds. Honolulu: Hardy Marks Publications.

Gilman, Sander. 1999. Making the Body Beautiful: A Cultural History of Aesthetic Surgery. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Govenar, Alan. 1996. American Tattoo: As Ancient as Time, As Modern as Tomorrow. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Groning, Karl. 2002. Decorated Skin: A World Survey of Body Art. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, Inc.

Hardy, Don Ed. 1997. Permanent Curios. Santa Monica, California: Smart Art Press.

Hardy, Don Ed. 2000. Tattooing the Invisible Man: Bodies of Work. Santa Monica, California: Hardy Marks Publications/Smart Art Press.

Kitamura, Takahiro and Katie M. 2001. Bushido: Legacies of the Japanese Tattoo. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Books.

Kuwahara, Makiko. 2005. Tattoo: an Anthropology. Oxford: Berg Publishing.

Mifflin, Margot. 1997. Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York: Juno Books.

Pitts, Victoria. 2003. In the Flesh: The Cultural Politics of Body Modification. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Randall, Housk, and Ted Polhemus. 1996. The Customized Body. London: Serpent's Tail Books.

Rubin, Arnold. 1988. Marks of Civilization. Los Angeles: University of California.

St. Clair, Leonard L., and Alan B. Govenar. 1981. Stoney Knows How: Life as a Tattoo Artist. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky.

Sanders, Clinton R. 1989. Customizing the Body: The Art and Culture of Tattooing. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Sanders, Clinton R. 1988. "Drill and Frill: Client Choice, Client Typologies,

and Interactional Control in Commercial Tattooing Settings," in

Marks of Civilization, Arnold Rubin, Editor. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History University of California.

Steward, Samuel M. PhD. 1990. Bad Boys and Tough Tattoos: A Social History of The Tattoo with Gangs, Sailors, and Street-Corner Punks, 1950- 1965. New York, NY: Harrington Park Press.

Sullivan, Nikki. 2001. Tattooed Bodies: Subjectivity, Textuality, Ethics,

and Pleasure. London: Praeger Publishing.

Trachtenberg, Peter. 1997.7 Tattoos: a memoir in the flesh. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Young, Katherine, ed. 1993. Bodylore. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press.

Notes

[1] Lyrics from The Tubes recording of "She's a beauty" 1982. [^]

[2] The human body as commodity is seen in the work of Clinton Sanders, Arnold Ruben, and Don Ed Hardy. Additional support for this idea can be found in the recent selling on Ebay of body spaces for tattooed advertising. [^]

[3] Notable are works by Clinton Sanders, Rubin Arnold, Tricia Allen, Jane Caplan, Margo DeMello, Margot Mifflin, Steve Gilbert, and Michael Atkinson. [^]

[4] Kuwahara describes her identity as being part of the unmarked in her introduction to her book, Tattoo: An Anthropology. [^]

[5] Steward, Samuel M. PhD. 1990. Bad Boys and Tough Tattoos: A Social History of The Tattoo with Gangs, Sailors, and Street-Corner Punks, 1950-1965. New York, NY: Harrington Park Press, introduction. [^]

[6] Some of these would be Spider Webb, Madame Chinchilla, C. W. Eldridge, etc. [^]

[7] An example of the difference between the tattoo community and the academic community is the use of the terms "tattooist" and "tattoo artist". While the academic community has moved smoothly from the older term of "tattooist" to the more current "tattoo artist," within the tattoo community the terms are still a matter of contention. For that reason, I use the terms interchangeably within this article so that both those who consider themselves tattooists and those who consider themselves tattoo artists may feel equally represented in my work. [^]

[8] One noteworthy collaboration that does bridge the gap is that of Leonard "Stoney" St. Clair and Alan B. Govenar in the 1981book, Stoney Knows How: Life as a Tattoo Artist, (Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky) and film of the same name. [^]

[9] See a discussion of legitimizing factors in the Conclusions of Sanders, Clinton R. 1989. Customizing the Body: The Art and Culture of Tattooing. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. [^]

[10] This may also be part of the underpinnings of the discussion of copyrights and tattooing that divides the tattoo artist community and is fodder for further discussion in a forthcoming article by this author. [^]

[11] Dye, Ira. "Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818" in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. [^]

[12] Gilbert, Steve. 2000. A Source Book: Tattoo History. New York, NY: Juno Books. [^]

[13] Two recommended works that go further into the circus and tattooing are "Totally Tattooed: The Self-Made Freaks of the Circus and Sideshow" by Steve Gilbert in Freaks, Geeks and Strange Girls: Sideshow Banners of the Great American Midway. (Johnson, Randy et al. Eds. 1995. Honolulu: Hardy Marks Publications.) and Margot Mifflin's chapter on women and the circus in Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo.(1997. New York: Juno Books.) [^]

[14] Dass, Rhonda. Forthcoming. Women in the Tattoo World: Identity and Display. [^]

[15] Sanders, Clinton. 1988. ""Drill and Frill: Client Choice, Client Typologies, and Interactional Control in Commercial Tattooing Settings," in Marks of Civilization, Arnold Rubin, Editor. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History University of California. [^]

[16] The issue of copyrights and protection of artistic work is a tricky one within the tattoo community. A recent article by Vyvyn Lazonga shows one side of the issue. (See "Tattoo Art 101 with Madame Lazonga" in Skin & Ink, June 2007, pg. 82-83, Fox Run Publications, Inc.) The standing of tattooing outside of a legitimized fine art classification complicates the issues of ownership through the commercial structure and production of tattoo work itself. While a design sheet or individual design can be copyrighted, the artistic expression utilized in the recreation of a design blurs the ownership along with the role of the collector in the tattoo process. I am currently researching an article on these issues and how they differ from the rest of the art community. [^]

[17] Gilbert, Steve. 2000. A Source Book: Tattoo History. New York, NY: Juno Books. [^]

[18] Dass, Rhonda. Forthcoming. "Negotiating Tattoo into Art". [^]

[19] Personal interview with Curse Mackey, September 8, 2003. [^]

[20] The evolution of the show Miami Ink from its earlier episodes, when I first began writing this article, to its current episodes, at the time of this revision in the summer of 2007, has drifted from the cultural narratives to a more aesthetic consideration. The artists narratives on why people get tattooed and why they tattoo have gradually been replaced with more audience pleasing depictions of personal conflict between individuals working at the shop and the outside interests of the shop owners. This has also brought about, in my opinion, a focus that falls in line with the accepted narratives that focus on the individual person collecting the tattoo and their individualism that further illustrates the points of this article. [^]

Return to Top »