404

Resource not foundWe apologize but this page, post or resource does not exist or can not be found.

Reconstruction 9.2 (2009)

Return to Contents>>

Flâneurs and Infiltrators (How to Read Cityscapes via Textscapes)/Joe Culpepper

Abstract

“Read your city anew” and “awaken from the spells cast by signs” are the mantras of this article. In Toronto, the radical spirit of revelation present in Walter Benjamin's Passagen-Werk (The Arcades Project) is embodied in an experiential approach to the capitalist city's hidden, forbidden, and inaccessible areas. Infiltration is a multifaceted phenomenon (a zine, a website, and a practice). The project is dedicated to the investigation, exploration, and mapping out of Toronto's abandoned buildings, defunct subway stations, luxury hotels, metropolitan marketplaces (i.e. the Hudson's Bay Company) and more. Circulated to encourage citizens of today's cultural metropolises to go where they are not supposed to, Infiltration is a postmodern form of historical materialism in praxis. Instead of awakening the sleepwalking consumers wandering Benjamin's nineteenth-century arcades, however, the zine is dedicated to snapping today's pedestrians out of their zombie like, routine-bound trances. This project, despite its strong theoretical and intellectually complex elements, is first and foremost a hands-on approach to (re)reading the urban environment—to demystifying the architectural cityscape. A look at the zine's unique form of production (its balance of textual and visual sources), its website's parallel existence with the text, and a close reading of its third issue concerning surveillance in the 21st-century marketplace reveals Infiltration's theoretical connections with and departures from The Arcades Project. Michel de Certeau's distinctions from L'Invention du quotidien (The Practice of Everyday Life) as well as J.L. Austin's and Della Pollock's conceptualizations of the performative all contribute to the article's argument that Benjamin's "flâneurs" and Ninjalicious's "infiltrators" are complimentary figures of resistance.

A high hedge of thorns soon grew around the palace, and every year it

became higher and thicker, till at last the whole palace was surrounded

and hidden, so that not even the roof or the chimneys could be seen.

- The Brothers Grimm, "Briar Rose"Ainsi la rue géométriquement définie par un urbanisme est transformée en espace par des marcheurs. De même, la lecture est l'espace produit par la pratique du lieu que constitue un système de signes — un écrit.

— Michel de Certeau, L'invention du quotidien

<1> We live under the spells woven by our current socio-economic conditions and communal superstitions. As we go about our lives in the world's urban centers, we are inevitably programmed by the everyday language we use and the well-worn paths that we tread. We order "grande" sized coffees from cafés that are not Starbucks, when what we want is a "medium" [1]. Out of fatigue, or during unexpected holidays, we find ourselves driving our cars or riding the subway to work only to realize, halfway there, that the building will be closed. The effect is one of daydreaming behind the wheel and then automatically retracing a familiar route. 'Automatic pilot' might be the phrase that best describes today's equivalent of what Walter Benjamin dubbed the "dreaming collective" [2], the sleeping masses of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

<2> A Dialectical Fairy Scene [3] was one of the original titles for Benjamin's Passagen-Werk [4], and reveals the importance of his consistent references to the "Briar Rose" or "Sleeping Beauty" myth. He imagined the commodity consuming masses, as reflected by forms of popular culture, to be stuck within a cycle of bewitchment. Like the king and queen's castle that becomes overgrown with thorn bushes to the point that not even its chimneys can be seen, Benjamin envisioned the abandoned nineteenth-century arcades as museums of capitalist decay and mystification; for him, these palaces contained treasures—relics, ruins, defunct commodities and fetishized fossils—that could be collected, researched, and represented to the masses through a montage of fragments (both textual and visual). His new brand of historical materialism was designed to blast open the forgotten past, to break through the enchanted rose bushes and to open the kingdom's eyes to reality—to lift the curse of the commodity and make clear its influence upon social life. Though he died before its completion, his most ambitious archival project was designed as "an experiment in the technique of awakening” [5].

<3> Walter Benjamin was inspired by what Karl Marx labels "the fantastic form of a relation between things," man's tendency to immediately separate the commodity from its original labor and its social relationship histories. In other words, humanity's obsession with the part while discounting the attached whole — the "fetishism" of the commodity [6]. The magical act of separating an object from its true nature, or the social origins of its production, occurs most frequently in the marketplace. This erasure of original meaning is often marked by an act of metonymy: a name change such as the shift from "medium" to "grande." Indeed these two materialist philosophers, if they were alive today, would no doubt be interested in the complex commodity exchanges taking place at so many Starbucks in so many parts of the world. Marketplaces of the Western world fascinated both thinkers, and both had different strategies for uncovering the mysterious activities taking place there.

<4> In Capital, Marx (1818-83), with his penchant for economic graphs, charts, figures and legal documentation, began a historical materialism of the nineteenth-century marketplace, which Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) reconfigured and reapplied to understand important technological and architectural shifts apparent to him in the 1920s and '30s. If the historical materialist's goal is to explain developments in human history according to material changes, then the explosive proliferation of photographic technologies and the appearance of new architectural designs (new combinations of iron and glass) [7] altered daily interactions between the consumer, the commodity, and the marketplace [8]. Furthermore, the world's first photographic exhibition (in 1855), the construction of the Eiffel Tower (1889), and the birth of film (circa 1895) all took place in Paris, where Benjamin completed most of his research. Phantasmagoria and the mesmerizing appearances, disappearances, and reproductions of images were all newer and more spectacular versions of the fetish process described by Marx. Therefore, it is no wonder that Benjamin's incomplete masterwork, his generative archive, The Arcades Project, emphasized the primacy of images and artwork as historical sources. Though I am tempted to further compare Marx, researching at London's British Museum in the mid nineteenth century, to Benjamin at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in the early twentieth, my current task is to examine a recent project taking place in another urban center - in Toronto, Ontario.

I. A Twentieth-Century Archive and Academic Archeology

La trace est ce qui nous reste. Elle peut être matérielle : une archive, un objet. Elle peut marquer un territoire : une stèle, un monument, et cela inuit une architecture, une épigraphie. — Jean-Yves Boursier, La mémoire comme trace des possibles [9 ]

<5> The Dialectics of Seeing is a reconstruction of a reconstruction. Susan Buck-Morss's book strives to (re)collect, supplement, and (re)conceive Walter Benjamin's unruly Passagen-Werk—the core archive of his scholarly career. Benjamin, in a more direct way, sought to preserve and represent the secret, hidden histories of the nineteenth-century Parisian arcades—early capitalism's commodity palaces—through myriad bits and pieces of consumer culture (advertisements, photographs, artwork, literary excerpts and other sources). One of the most intriguing and problematic aspects of Buck-Morss's project is its attempt to emulate its subject's unique approach to the detective work of historical materialism.

<6> Just as the Passagen-Werk emphasized the crucial need for images to express the arcades’ urban environment, The Dialectics of Seeing makes a concerted and successful effort to present its analyses through photographs and other visual aids. Its structure also reflects a Benjaminian penchant for mythical figures and tales which, like the text's many photos, act as narrative hooks that pull the reader through and into early (nineteenth-century) and high (twentieth-century) capitalist realities (or quasi-realities). Through her invocations of the "Sleeping Beauty" motif, her textual/visual argumentation, and her knack for biographical intrigue, Buck-Morss creatively mixes genres, narrative techniques and materials to resurrect Benjamin's arcades and their collective ghosts.

<7> However, literary, historical, and philosophical criticism in the English-speaking world is not known for its privileging or adept use of visual materials (though with the efforts of academic journals such as Reconstruction this is changing). In the writing, organizing, and publication processes typically used by these disciplines, textual descriptions come first and photographs are wedged into them afterwards. This method for a text's construction is only natural considering its place of origin: the university. But how might the steps of this intellectual process be reversed? The answer can be found in a postmodern incarnation of The Arcades Project. In Toronto, the radical Benjaminian spirit of revelation is embodied within a more experiential approach to the capitalist city's hidden, forbidden, and inaccessible areas.

II. A 21st-Century "Zine": Urban Exploration

I kept telling the same stories that went along with the pictures over and over again, writing these stories on the backs of the pictures as well, and eventually it occurred to me that it would make sense to photocopy these pictures along with the stories and to put that out as a "zine" [10]. - Ninjalicious [11]

<8> Infiltration is a multifaceted phenomenon (a zine, a website, and a practice). The project is dedicated to the investigation, exploration, and mapping out of Toronto's abandoned buildings, defunct subway stations, luxury hotels, metropolitan marketplaces (such as the Hudson's Bay Company) and more. Circulated to encourage citizens of today's cultural metropolises to go where they are not supposed to, Infiltration is a postmodern form of historical materialism in praxis. Instead of awakening the sleepwalking consumers wandering Benjamin's nineteenth-century arcades, however, it is dedicated to snapping today's pedestrians out of their zombie like, routine-bound trances. This project, despite its strong theoretical and intellectually complex elements, is first and foremost a hands-on approach to (re)reading the urban environment and to demystifying the architectural cityscape. A look at the zine's unique form of production (its balance of textual and visual sources), its website's parallel existence and virtual supplementation of the text, followed by a closer reading of its third issue concerning surveillance in the 21st-century marketplace will reveal its theoretical connections with and departures from The Arcades Project. Finally, some of Michel de Certeau's distinctions from L'invention du quotidien (The Practice of Everyday Life) will return us to the tiny battles of daily life in the capitalist, consumption-controlled cityscape and inform a comparison of Benjamin's "flâneur" to Ninjalicious's "infiltrator" as protagonists of resistance.

<9> In my 2005 interview with the alias-protected author and editor of Infiltration [12], I was intrigued to learn that the project's birth first came about through physical action, then photographic records, and, lastly, the addition of written text. In other words, the black and white, independently published magazine began as fieldwork. Infiltration's textual fragments (transcribed stories), as this section's epigraph suggests, came as an afterthought. Benjamin, who saw only the initial proliferation of photographic technologies and methods of reproduction, might be pleased to see this powerful employment of the digital camera. The zine takes full advantage of technology to transgressively document abandoned and broken down urban niches deemed too dangerous for public exploration. In the sense of historical materialism, the low-cost photocopying and digital dissemination of the text's materials reflect a positive change in technological circumstances that allow for the zine's existence with minimal interference from the massive machinery of corporate publication. Unfortunately, later on in my analysis, these same technological advances will point to more negative aspects of capitalism's current domination of city space.

<10> Since its humble beginnings in 1996, the zine has put out 25 separate issues and filled nearly 600 pages with an even-handed balance of textual descriptions and visual representations [13]. These pages are dedicated not only to the practice of "urban exploration"; they also discuss the theory, ethics, and practical tools needed to participate in the art of infiltration. In many ways, the zine is more like an instruction manual on how to penetrate the forgotten and neglected recesses of unusually beautiful or decaying buildings. Certainly, its photographs, graphic maps, and textual explanations are meant to be read and enjoyed—in a moment, examples will show how these elements are thoughtfully and poetically related—but the zine's greatest purpose is "to get people exploring [14],” as Ninjalicious told me himself.

<11> The pragmatic need to transmit a different level of spatial detail, and the author's ability to seamlessly blend descriptions of places with photos of them, make for a more authentic and unique version of what Buck-Morss's "Afterimages" section attempts at the end of her book [15]. Granted, her text's goal is to recreate the intellectual impact of juxtaposing images in a "dialectical," Benjaminian style; however, her photomontage too closely mimics images withdrawn from The Arcades Project's data bank. The combinations seem awkward, because the ultimate reason for images being placed next to one another is more for suggestion than for statement. Her photo essay comes across as expository and somewhat contrived.

<12> Infiltration, on the other hand, creates a strong and sustained dialogue between its photos and text. Its format allows for a dialectical juxtaposition of the superficial exterior of a local building, to its previously inaccessible or invisible interior (its hidden nature). The zine can either be read, experienced, or both. Even if the reader does not use the text as a technical manuscript, its contents transmit an intimate, nearly experiential knowledge of familiar landmarks in Toronto's cityscape. The images are powerful enough to create an almost tangible texture of place. During my interview with Ninjalicious, he described the strong emotions that are aroused when he returns to a location once known as "Festival Hall [16].” The Paramount Theatre now stands in its place, but the author of Infiltration explored it during its (re)construction (while it was in the process of archi-text-ural metonymy: urban name change). Now, when he visits the movie theatre, he imagines the place as it was before completion: "I can remember how the carpet looked before it went in place and back when the escalators were just hanging in midair from one cement slab to another . . .” [17]. I asked him if the emotional proximity expressed via his zine's treatment of the building resulted from his experience of watching its (re)birth:

N: Yeah, it's like when it was born. It's also, to look at it a different way, like seeing a building in its underwear. And you know, once . . . you're always going to . . .

J: . . . (laughing) the relationship has changed . . .

N: . . . yeah, there's always going to be an intimacy there, there's always going to be a "well, you can kid with other people, but you can't kid with me" kind of thing. [18]

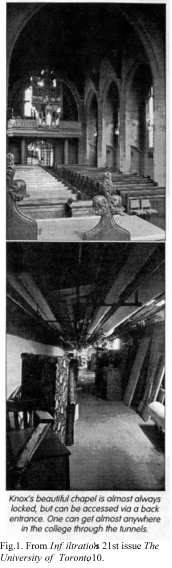

The fact that these photos were taken first-hand, that they are fruits of experiential labor rather than gathered from an academic archive, communicates a more intimate understanding of the exploration process. If only Benjamin or Buck-Morss had had digital cameras to record their trips through the arcades.

<13> With its more experiential approach, Infiltration makes a sincere attempt to awaken its reader to new ways of seeing and new tactics of urban navigation. The result is a natural combination of theory with practice and of text with images. The zine's use of photos and narratives, which sometimes parodies tour guide conventions [19], demands a truly active reader: a participant. The zine breaches the gap between life and literature, between cityscape and "textscape" — between participant observation and participant reading.

<14> Infiltration also exceeds the limits of the paper it is printed on through simultaneous existence as a hypertext. The publication's double life, as both a virtual (on the web) and a physical (off the web) zine, adds further layers to the social relationships generated within its reading community. Aside from offering an extremely professional and easily navigated layout of the black and white zine's textual content, the website also provides color versions of the photographs it publishes. The electronic version of Infiltration contains links to similar "urban exploration" or "urban archeology" projects around the world, an "Infilspeak" dictionary, a historical timeline of urban exploration's development as a phenomenon and more. In this sense, the multidimensional, virtually interactive side of Infiltration creates a readership engaged in hypertextual communication with various sympathetic communities. Its dictionary of specialized terminology builds subculture through common linguistic practices and codes. Virtual participation in the study and practice of infiltration is only one of the many ways that readers become part of this project as a whole.

<15> To further understand the myriad operations through which a participant reading can take place, it will be necessary to make some terminological distinctions. By exploring concepts of "place" vs. "space" and "cityscape" vs. "textscape," I will examine how Infiltration teaches its readers to create new kinds of spatial stories: to see and interact with their city, on a daily basis, in convention-breaking ways.

III. Transgressions: The Camera-Covered Marketplace; The Sign-Covered Building

I find it sad that most people go through life oblivious to the countless — free — wonders around them. Too many of us think the only things worth looking at in our cities and towns are those safe and sanitized attractions that require an admission fee. It's no wonder people feel unfulfilled as they shuffle through the maze of velvet ropes on their way out through the gift shop.

— Ninjalicious, from Infiltration's websiteHabits look not only backward but also forward. . . . “We may think of habits as means, waiting, like tools in a box, to be used by conscious resolve,” John Dewey wrote. “But they are something more than that. They are active means, means that project themselves, energetic and dominating ways of acting.” Habits are living practice, the site of creation and innovation.

— Hardt and Negri, Multitude

<16> Today's postmodern version of Benjamin's nineteenth-century Arcade would have to be the various malls, commercial centers, and tourist attractions that permeate the city. By perusing a few particular sections of Infiltration which focus on the often purely psychological security measures used to control public places, I argue that the resistant reading practices required for urban archeology today reveal significant changes in the marketplace (security cameras), the urban environment (public signs), and subvert the normalization of navigation practices. Libratory exploration demands transgressive habits.

<17> In "Récits d'espace," Michel de Certeau speaks of the "spatial stories" created by the daily interactions between pedestrians and their city environments. He makes a crucial distinction between "espace" (space) and "lieu" (place). A "place," like a city street, is a fixed or stable location and is not so different from a standardized text. A "Space" is created the moment that pedestrians animate the street (moving forward with their feet) or the moment someone begins reading the daily tabloid (advancing their eyes from left to right). "Space," in other words, is a practiced "place"—"l'espace est un lieu pratiqué” [20]. But what happens when I read "Enter" vs. "Introduction?" How do the phrases "Dead End" and "The End" operate similarly? These textual instructions tell me where to begin and where to terminate my journey. As street signs or book divisions, these markers attempt to control and guide the construction of a spatial story. This is the "preface," says the editor of the novel; "continued in section B-5," directs the editor of the newspaper. Once I form such habits, as always beginning a book at its introduction or always waiting for the crosswalk to turn green before I recommence walking, then I have taught myself a type of reading and treading practice — a treading — that automatically guides my movement from place to place, thereby limiting my potential for spatial (re)creation. This limitation of consumers' facility to experiment, to create new and different spatial stories brings us back to the 'automatic pilot' condition previously discussed.

<18> If Benjamin strove to awaken the masses of his day from the mystified slumber induced by phantasmagoria and other phenomena, then Ninjalicious similarly urges his readers to break through the psychological spells cast by security cameras and "official" signs. His goal is to reveal buildings' interior secrets. In a section titled "Warning Signs: How to Ignore Them” [21], Ninjalicious tackles the most menacing of the sign species one might encounter in a building: "Fire Exit" signs, "No Trespassing" signs, "Danger: Do Not Enter" signs, and "Authorized Personnel Only" signs. "We have allowed these signs to repress us for too long!" says Ninjalicious of these magical phrases, which have the power to make one change direction without a second thought. Here, the reader learns that "Fire Exit" signs are frequently posted on doors that are "bluffing," because they are not connected to the doorframe with the necessary wiring. In the emancipatory game of urban exploration, infiltrators must learn to call such bluffs and to question the architectural assumptions they have been taught to make.

<19> Indeed, anytime I read the word fire in public place, with letters emblazoned in red, a psychological bell goes off in the back of my mind and an irresistible force wards me away from that door. Breaking the convention of a building by walking through an "off-limits" door is akin to reading the last page of a book first—it simply is not done; such a reading is against the supposed rules. However, in a marketplace, and an increasingly corporatized city, where more and more "Authorized Personnel," "Employees Only," and "Staff Only" signs are being hammered into place, Ninjalicious relates that he once had a job where he was allowed to enter "authorized" areas [22]. He then gives his text a performative tone when he uses his past "official" status to baptize readers: "I feel no qualms about hereby authorizing all who read this article to access any area which you feel like accessing. Now you're authorized" [ 23].

<20> In other words, Ninjalicious fights the performative language of building signs with performative writing of his own. J.L. Austin defines "performatives" as those words that "do what they say" [24]. In response to corporate centers of commodity exchange and their attempts to interpolate us as "unauthorized," the language of the zine allows its reader to now interpret the sign as an invitation—the reader, through the formation of a new habit (a new reading practice) is liberated.

<21> In "Performing Writing," Della Pollock takes this concept one step further. A performative perspective," she says, "tends to favor the generative and ludic capacities of language and language encounters—the interplay of reader and writer in the joint production of meaning" [25]. This concept captures the childlike mischievousness and the ludic pleasure expressed by Infiltration. Marriages of photographs with textual descriptions are often underscored by the author's visual word games. For example, in his guide to the exploration of Toronto's City Hall, Ninjalicious makes his words perform an optical illusion to simulate the experience of reading a building in the resistant manner required for infiltration: "Eventually the main hallway leads out through a set of glass doors marked 'No Admittance Except On Business,' ('ssenisuB nO tpecxE ecnattimdA oN' to you) and out into the employee cafeteria section of the basement" [26]. At moments like these, I justify my use of the word "textscape" to describe the effect created by a view (or "–scape") of a real place (City Hall, in this case) that enters into a direct relationship with the "cityscape." Not only does Infiltration alter the theoretical manner in which we read signs or react to them, it also captures the little details of specific locations with a special clarity. If I go to Toronto's City Hall, I am determined that I will be walking into the building with such a strong subtext (acquired through this zine) that the place will seem oddly familiar. Because I have already tread the building "sadrawkcab" ("backwards") via Infiltration's "textscape," a trip to the real government building will be my second experience of the place. In such cases, the particular intertextual relationship between the cityscape and the "textscape" is especially direct. Although a similar effect can be created by works of fiction (such as descriptions of famous monuments) the exaggerated nature and fictive ends of such work almost always result in a feeling of disappointment when the real physical location is finally seen. A zine determined to map and record only the most important security details, and the most glorious secrets of a local living and breathing location is closer to a new brand of historical materialism or urban anthropology.

<22> In his third issue, Ninjalicious finally gets an interview with a security officer in response to the requests that appear on the last page of each issue. Along with calls for outside submissions and a short preview of articles to come, the zine consistently shows interest in speaking to those that are (or were) on the other side of the electrified fence. Though the historical significance of this issue is minimal, the Hudson's Bay Tower (1974) is not old enough to truly interest the author's antiquarian side, studying the human element of its security system is of extreme interest to the urban detective. The anthropological technique of acquiring an informant is a bold and intriguing move. John, a former security supervisor of the building, reveals stunning details about the pragmatic realities surrounding security cameras and their limitations within intimidating corporate buildings: the reality of one person at a desk attempting to keep track of 15 different monitors is one example.

<23> In the second part of the same theory heavy issue, the reader is provided with a detailed catalogue (12 different, crisp photos) of the many security cameras used in commercial urban centers such as Hudson's Bay Tower. "Surveillance," as Ninjalicious says, "is a sad fact of modern exploration – so read carefully" [27]. To ensure that we can tread carefully, visual and textual details are given describing various cameras strengths and weaknesses and their two main categories: covert or non-covert. Even an advertisement for a "Reproduction Security Camera!" and its photograph are reproduced to prove that "fake" cameras (like fake L.E.D. car alarms) are being sold as strictly psychological deterrents. The "panopticon" (or self-surveillence) [28] effect of non-covert cameras is so powerful that corporations and buildings frequently do not maintain or replace their older cameras. "Cameras are often used to intimidate rather than gather information," explains the article, which contains a photo of a camera in Toronto's Queen subway station that "still has the lens cap on" [29]. The "someone-is-watching-you" spell of the post-modern marketplace (and other urban places) is so powerfully cast by the form and shape of these disturbing devices that pedestrians automatically avert their gaze. It is against all social conventions to look at a camera long enough to judge how old it is or if it functions—no one checks the lens cap. Infiltration instructs the reader to think again and to read more closely.

<24> I have argued that Certeau's theoretical comparison of seemingly disparate daily activities (reading, walking, etc.) is exemplified by the Infiltration project, which reveals the influence of new technologies in the creation of both text space ("textscapes") and city space (cityscapes). To reiterate, the combination of a text and its reader generates a "space" (a "view" or "-scape" of a text); likewise, the pedestrian's navigation of an urban location (a building or street, etc.) also creates "space" (a way of seeing or "-scape" of a location). Infiltration is a case study of the direct and complimentary interactions between cityscapes and "textscapes," which operate at new levels due to new technologies. These two reading practices or navigation techniques (ways of reading and ways of seeing) come together — they operate in tandem. At this point, The Dialectics of Seeing and Benjamin's original Passagen-Werk have focused my discussion on the theoretical and physical constructions and approaches of these projects. A discussion of the texts' materials, their diverse applications of historical materialism, and some biographical information about their authors has provided an understanding of the cities and marketplaces they discuss. To further question the interaction between literatures, the city, and how capitalist consumers (inhabitants of Western cities at least) perform their daily activities, I now turn to the figures of resistance (or literary protagonists) presented by The Arcades Project and Infiltration. Benjamin's "flâneur" and Ninjalicious's "infiltrator" represent general categories, or character types, which offer unique possibilities for new spatial navigation techniques in the capitalist cityscape.

IV. Flâneurs and Infiltrators

The man who hasn't signed anything, who left no picture,

Who was not there, who said nothing:

How can they catch him?

Erase the traces. — Benjamin quoting Brecht, "On the detective novel"The motto of the Sierra Club is 'take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints.' I would say that we have the same motto except we shouldn't bother leaving footprints either. — Ninjalicious

<25> Benjamin's collected fragments regarding the flâneur and the Parisian cityscape are just that—fragments. It is difficult to clearly define the figure that he calls the "flâneur" or the practice of "flâneurie," because he draws from such disparate cultural sources: Baudelaire's poetry, a restaurant's voluminous menu, Marx on the commodity, personal experiences, and the words of Bertolt Brecht to name just a few. Furthermore, it is impossible to quote Benjamin without quoting someone else. His observations are minimal as to not distract from the textual or visual fragment that his project presents; oftentimes, they are embedded and inseparable from the excerpts used. Working with Benjamin forces critics to cite one author through another.

<26> One dangerously complicit figure of rebellion mentioned by Benjamin is the idle "flâneur." "The idleness of the flâneur is a demonstration against the division of labor," he suggests [30]. He often refers to the idle or lazy "flâneur" as a passive aggressive consumer rebel. Some of these "flâneurs" are radicals such as Baudelaire, Flaubert, or Dickens; some of them are detectives and bohemians; sadly, some of them are less extreme or even servile participants in the capitalist economy. The idleness of the "flâneur" is appropriated by the later and more developed versions of the Parisian arcade—in fact, his laziness is capitalized upon. The ultimate failure is the "flâneur" as a living advertisement for the commodity-exchanging marketplace: "The sandwich-man is the last incarnation of the flâneur" [31]. Though this last quotation suggests the death of the resistant "flâneur," Benjamin does offer a range of "flâneur" types—a fragmented, synchronic history of their evolutions—and suggests a strong connection between the spaces produced by the daily practices and apparently aimless wanderings of nineteenth as well as twentieth-century pedestrians.

<27> His most frequent portrayal of this protagonist of the arcades describes the "flâneur" as a dissimulating detective. This incarnation of the "flâneur" emulates many of the techniques used by infiltrators: subtle acting, stealth, and clandestine observation. There is still hope for Benjamin's "last" incarnation of the "flâneur." The contemporary sandwich-man by day may transform into an infiltrator by night. In fact, Benjamin describes this undercover side of the "flâneur" as intrinsic to the figure’s ontological nature:

Preformed in the figure of the flâneur is that of the detective. The "flâneur" required a social legitimation of his habitus. It suited him very well to see his indolence presented as a plausible front, behind which, in reality, hides the riveted attention of an observer who will not let the unsuspecting malefactor out of his sight. [32]

As a figure of resistance, the flâneur can be described as a loitering sloth turned sleuth. The infiltrator adapts this same detective skill to the practice of observing a building's security precautions behind the subterfuge of a disinterested businessman or a bored window shopper. Ninjalicious often speaks of using disguises or merely affecting a careless attitude to surreptitiously record the secrets of an urban environment for later exploitation. Indeed, during our conversation, he explained the importance of both "staying in character" when conducting in-the-field research of buildings such as the Hudson's Bay Tower [33]. By blending in with the shoppers at a commercial center or patrons at a luxury hotel, the infiltrator is able to cautiously compile details that allow for further access during future visits. Therefore, the time and research that goes into familiarizing oneself with a building (its passageways and its construction history) is substantial. "Something like the Royal York, or St. Michael's Hospital, or the Hudson Bay Company would have been examined intensely, just that building, for half a year," explains Ninjalicious [34]. Much of this work is accomplished using what he dubs "credibility props," which would be the equivalent to a private-eye wearing a false mustache or dressing up as a window cleaner. Infiltration "exposés" almost always include a list of specialized items or "simple objects that in some way radiate believability and belongingness" [35]. Business suits for fancy hotels, in-patient robes for hospitals, headsets and clipboards for media or office buildings are all disguises recommended depending upon the urban environment to be explored. An infiltrator might have the same wardrobe as a detective.

<28> With a combination of stealth, acting, and persistence, the infiltrator, like the "flâneur" often travels deeper within a building than even its staff or employees. The detailed interior of a building—its security cameras, its motion detectors, its fire-exit door alarms, its elevators, its "employees and staff only" signs—are all recorded by the dead-pan face of the infiltrator as he asks for directions to the nearest bathroom. Useful information is stored and archived by the urban explorer for later use. In many ways, the "flâneur" and the infiltrator are incarnations of the same human desire to resist the marketplace environment. Though separated by an ocean, a century, and rapid developments in the capitalist urban center's architecture, these figures both tap into a basic human desire: the desire to write one’s own story. New treadings and re-treadings make way for new writings.

<29> Benjamin's selected fragments make clear the "flâneur's" desire to break through the common barriers that block the average passer-by's trajectory through nineteenth- and twentieth-century arcades. To epitomize the arcade detective's transgressive desire to navigate beyond ordinary and superficial boundaries, the author uses an excerpt from Daniel Halévy's Pays parisiens (1932): "Maxim of the flâneur: 'In our standardized and uniform world, it is right here, deep below the surface, that we must go. Estrangement and surprise, the most thrilling exoticism, are all close by'" [36]. Venturing below the surfaces of the urban world is the "flâneur's" "raison d'être." The "exotic" nature of the "flâneur's" decent into strange and unfamiliar territory is echoed by the tone of Infiltration's multiple issues on subterranean subjects like "tunnel running," mapping the Parisian Catacombs, and the many articles detailing adventures through metropolitan subway networks (everywhere from Toronto, to Minneapolis/St.Paul, to Glasgow and Milan) [37]. But flâneur-like exhilaration is best described in one of the zine's pieces devoted to steam tunnel exploration in North American Universities. In "Tentanda Via" (Latin for "the way must be tried"), Ninjalicious links the adrenaline producing activity to a type of sexual excitement: "What is it that makes steam tunnels so sexy? The darkness? The dirt? The danger?" [38] Just as Benjamin's chosen maxim for the "flâneur" emphasizes the addictive thrill of "estrangement" to be had by traveling beneath the normal world's surface, Ninjalicious suggests that "the rush created by the naughtiness of being in the highly off-limits tunnels inspires us towards further naughtiness" [39]. In other words, the exotic and illicit nature of exploring unknown regions of public places — a taboo-breaking exploration of a building's dirty, underground history — is sexy. The allure of the unknown and undiscovered places beneath the city pulls urban explorers into the depths.

<30> This sexual quality of the infiltration experience, however, is also mixed with the power derived from intimate knowledge of a building and the tracing of invisible connections between the old and the new — the past and the present. The action of opening locked doors and crossing a place's boundaries generates a unique sensation of familiarity. Benjamin explains that "flânerie can transform Paris into one great interior—a house whose rooms are the quartiers, no less clearly demarcated by thresholds than are real rooms—" [40] likewise, the art of inflitration collapses Toronto's public and private spaces. A cityscape without thresholds—where public spaces are reclaimed—is created using the urban archeologist's power to access and link together forbidden places.

<31> In an issue devoted to mapping the many colleges at The University of Toronto, these self-proclaimed "interior tourists" reveal the myriad underground passageways connecting the following colleges: "Wycliffe (1891), Wordsworth (1893), Knox (1915), New (1965) and Innis (1976)" [41]. As shown by this example of Infiltration's knack for photo/text montage (see fig.1.), the publication revels in both the act of historicizing these colleges and in uniting their disparate, seemingly independent architectural structures. "One can get almost anywhere in the college through the tunnels," claims the caption adorning the above/below views of Knox College's chapel. By entering through the back door (which frequently lies below the surface) and traveling behind the architectural scenes, the infiltrator realizes the power of secret passageways. The zine's expository narrative and demystifying project rejoices as it breaks down barriers denying access to these places and separating them from one another. The reader is awakened to the interconnected reality of the U of T, which will remain invisible to the passive, aboveground public. "So much for the colleges which feign semi-independence," states a satisfied Ninjalicious [42].

<32> The detective-like infiltrator at play in the tunnels connecting the Toronto cityscape's buildings and structures of varying ages enjoys the same kind of adrenalin-induced jubilation Benjamin saw in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century "flâneur." He insists that "flâneurie's" most climactic discoveries in the arcades and Paris occur when "far-off times and places interpenetrate the landscape and the present moment. When the authentically intoxicated phase of this condition announces itself, the blood is pounding in the veins of the happy flâneur" [43]. Here, Benjamin is speaking of "flâneurie" as an art, or urban indulgence, and sees its greatest rewards as moments when time and place "interpenetrate" and happily collide with the "flâneur's" present. The same visceral sensation of temporal and spatial displacement is described when Infiltration recounts the fantastic discovery of a fake subway stop in Toronto's TTC system. The tension and the nerve-tingling pleasure of the infiltration process can be felt in the story's retelling: "When we finally glimpsed the abandoned station's white tiles just around the corner, our hearts pounded. The legend was real. Forcing ourselves to remain quiet, we slowly inspected the platform for signs of cameras or motion detectors" [44]. In the moment described, legend becomes reality and the rumors of a defunct TTC railway station now used for movie locations (and other purposes) materialize to fill the infiltrator's present. The terror of the unknown is mixed with the "jouissance" of spatial transgression's rewards.

<33> The authors of this story navigate dangerous subway tunnels (strictly off-limits to the public) and bring to light the eerie existence of a fully functional subway station (hidden beneath the surface of Toronto's streets and absent from TTC transit maps). "It's a little known fact that Museum, St. George and Lower Bay Stations are connected in a Y-shape," states Ninjalicous. "Lower Bay" was the name of the now forgotten station, which the issue informs us was only in public use for a few months in 1966 [45]. With this mixture of a first-hand, experiential account and research regarding the subway's history and construction, a small version of the infiltration or "flâneurie" experience is transmitted to the reader. A ghost station is brought back to life and reconnected to the TTC system every time an Infiltration subscriber (re)reads Toronto's colorful and prominently posted maps with a new subtext in mind. The urban commuter, even if they do not take the initiative to explore the grimy tunnels themselves, is taught to read in between the lines of the "official" schematics provided. Thanks to trailblazing infiltrators, certain members of the nine a.m. to five p.m. workforce will approach the subterranean urban world with a new understanding of its historical secrets. Being able to imagine the possible depths of subway systems and complex urban structures is the first step towards navigating them in a new way. Breaking through cityscape thresholds, whether in Paris or Toronto, and (re)mapping the tunnels that bridge the gap between otherwise fetishized or disconnected locations, the infiltrator and the "flâneur" continue their quests.

V. (In)conclusions

Habiter, c'est narrativiser. . . . Il faut réveiller les histoires qui dorment dans les rues et qui gisent quelquefois dans un simple nom, pliées dans ce dé a coudre comme les soieries de la fée. — Michel de Certeau, L'invention du quotidien : 2. habiter, cuisiner [46]

<34> Will the spell of capitalist mystification be lifted from the urban kingdoms of the current millennium? Can the "automatic-pilot" masses be inspired to take the navigation controls back into their own hands? By examining two unusual projects (the Passagen-Werk and Infiltration), their mixture of images and text, their liberating goals, and their protagonists, I have questioned how interactions between the cityscape and the "textscape" change in moving from Paris to Toronto. I have also established a "rapport," an urban solidarity, between the "flâneur" and the infiltrator. They are simultaneously detectives, actors, and excitable explorers dedicated to new understandings of their cityscapes through further—interior—exploration. I must emphasize the fact that both Walter Benjamin and the mysterious Ninjalicious travel within and beneath the surface of the cities captured by their texts. The former provides more theoretical tools, while the latter offers more practical and contemporary ones, but both authors present figures who break with convention to express their own spatial stories. Furthermore, the hobbies, pastimes, and ways of urban life described are emancipatory and exhilarating celebrations of the spirit of discovery.

<35> Of course, Benjamin's "flâneurs" did not have to scan the rooms of Paris for motion detectors or security cameras. Many differences in today's rapidly changing marketplace, which has left the former boundaries of the arcade to appear on every street corner, surface within Infiltration's text. New technologies are influencing both the physical appearances of urban metropolises and the ways in which those appearances are processed. Just as photography, in Benjamin's day, required a new mental conceptualization of light's properties and the nature of celluloid (or "the plastic arts" as film is sometimes called), video and computer technologies demand a new type of spatial literacy in the current millennium—a virtual and multi-dimensional imagination. Though I did touch upon Infiltration's existence as both text and hypertext, the many rich allusions made to video game titles in the zine's pages and their deeper significance deserve critical attention. The heart-pounding moment experienced by "flâneur" and urban explorer alike was explained to me by Ninjalicious as "the same nervousness when you enter a room in the video games" [47]. Not only did the author grow up playing video games and experimenting with hacking, many specialized terms used in his narration and in his readers’ printed letters come from hacker slang [48]. Cyberpunk fiction authors, such as William Gibson, have written stories about the combination of virtual "hacking" (gaining forbidden access via computer) and physical infiltration (gaining forbidden access in person). How do our nearly daily interactions with computers and our navigation practices (our exploration of websites) inform our navigation of real sites — physical locations? What spatial conventions are we learning to follow? What new capitalist influences dominate our reading and viewing techniques? Is the fact that the corporate name "Google" has become the verb "to google" good, bad, or merely indicative of the forces historical materialism seeks to understand? The next step in an exploration of the "textscape," of its interaction with the cityscape and of tactics for reader resistance are suggested by such linguistic fragments.

Works Cited

Austin, J. L. How to do Things with Words. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1975.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Edited by Rolf Tiedemann. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002.

Boursier, Jean-Yves. "La mémoire comme trace des possibles." Socio-Anthropologie, no. 12, (2002), http://socioanthropologie.revues.org/document145.html (accessed February 5, 2009).

Buck-Morss, Susan. The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1989.

Certeau, Michel de. L'Invention Du Quotidien : 1. Arts De Faire. Edited by Luce Giard, Paris: Gallimard, 1990.

———, Luce Giard, and Pierre Mayol. L'Invention Du Quotidien : 2. Habiter, Cuisiner. Paris: Gallimard, 1994.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish : The Birth of the Prison. 2nd Vintage Books ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire. New York: The Penguin Press, 2004.

Infiltration. 2005. http://www.infiltration.org/index.html (accessed February 5, 2009).

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin in association with New Left Review, 1990.

Ninjalicious. Danger and Deviousness at City Hall. Issue 8.*

———. The Guts of St. Michael's Hospital. Jan. 1997.

———. Hudson's Bay Centre Security. March 1997.

———. Looking Out For You. March 1997.

——— and Joe Culpepper. Ninjalicious Speaks. April, 8th 2005 (unpublished interview).

———. Paris Catacombs; Italian Subways; Scottish Rail Tunnels. Issue 9.

———. Secret Stations; Exploring Subway and LRT Tunnels. Issue 5.

———. Tentanda Via at York University; Tunnel Running 101. Issue 4, 2.

———. Toronto Hotels; Luxury Leeching Dallas Style. Issue 6.

———. Twin Cities Spectacular. Issue 20.

———. Under Construction: The Sheppard Subway and Festival Hall. Issue 13.

———. The University of Toronto. Issue 21.

Pollock, Della. "Performing Writing." In Performance Theory. Edited by Richard Schechner. New York: Routledge, 2003, 73-103.

* After the first three issues of Infiltration, dates are no longer provided and only issue numbers are given.

Notes

[1] The front page of The New York Times, 15 March 2005 ran a story about consumers' small, quotidian acts of resistance such as refusing to use words like "grande" while ordering their coffee. The article also cites James Scott's Weapons of the Weak and his analysis of passive resistance tactics. [^]

[2] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002), 389. In "Convolute K" of his archive, Benjamin states that this "dreaming collective," as it wanders through the arcades "communes with its own insides." Both the 'K' and 'L' sections of Benjamin's collection focus on the dream houses of capitalism.[^]

[3] Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1989), 34. [^]

[4] The Arcades Project and its German title are used interchangeably throughout my discussion.[^]

[5] Benjamin, 388.[^]

[6] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. (Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin in association with New Left Review, 1990), 165.[^]

[7] Buck-Morss, 111. In The Arcades Project, Benjamin discusses the way architects initially tried to build with iron as if it were wood. He often analyzes the way Parisian architecture reflects humanity's struggle to cope with and adapt to new technologies.[^]

[8] In addition to Marx, the work of sociologist Georg Simmel had a strong influence on Benjamin's analysis of the nineteenth-century city. One of Simmel's most interesting contributions to The Arcades Project is related to the effects of glass and iron upon commuters' social interactions (for his discussion of citizens being forced to "look at one another without talking to one another," see Benjamin, 433-434).[^]

[9] Jean-Yves Boursier, "La mémoire comme trace des possibles," Socio-Anthropologie, no. 12, (2002), http://socioanthropologie.revues.org/document145.html (accessed February 5, 2009). [^]

[10] "Zine" is an abbreviation of the word "magazine" and is used to describe small, independently produced publications, which are often artistic combinations of words and artwork. They are sold in comic book stores, independent bookshops, and a small number of mainstream bookstores. By now, the term is so established that I feel no obligation to treat it as a specialized one requiring quotation marks.[^]

[11] Ninjalicious and Joe Culpepper, Ninjalicious Speaks, April, 8th 2005 (unpublished interview).[^]

[12] Five months after my interview with Ninjalicious, I received the sad news that he had died of cancer. His friends and family knew him as Jeff Chapman, but most readers of Infiltration knew him only by his pseudonym. [^]

[13] Ninjalicious's final manuscript, a book titled Access All Areas, appeared mere weeks before his death in 2005. That publication extends the work he began with Infiltration.[^]

[14] Ninjalicious and Culpepper, (April, 2005).[^]

[15] Buck-Morss, 341-375. The images in this section feel loosely connected.[^]

[16] This building is covered and photographed in issue no. 13: Under Construction: The Sheppard Subway and Festival Hall, 24-28. [^]

[17] Ninjalicious and Culpepper, (April, 2005). [^]

[18] Ibid., (April, 2005). [^]

[19] For example, the zine's sixth issue is mainly composed as a guide to Toronto's classiest and most easily infiltrated hotels. Ninjalicious recalibrates the standard one to five star rating system and uses it to compare amenities available to the "non-guest" (the infiltrator): ease of pool access, the variety of saunas and hot tubs, and the quality of complimentary food and drink. [^]

[20] Michel de Certeau, L'Invention Du Quotidien : 1. Arts De Faire. Edited by Luce Giard, Michel de Certeau et al. (Paris: Gallimard, 1990), 173. [^]

[21] This section appears in issue no. 2: The Guts of St. Michael's Hospital, Jan. 1997. 19-20. [^]

[22] Ibid., 20. [^]

[23] Ibid., 20. [^]

[24] J. L Austin, How to do Things with Words, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1975), 25. [^]

[25] Della Pollock, "Performing Writing," in Performance Theory, Edited by Richard Schechner (New York: Routledge, 2003), 80. [^]

[26] This quote appears in issue no. 8: Danger and Deviousness at City Hall, 10. [^]

[27] This section appears in issue no. 3: Hudson's Bay Centre Security, March 1997. 19-20. [^]

[28] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish : The Birth of the Prison (2nd Vintage Books ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 169-228. See his study of Jeremy Bentham's "Panopticon" and the architectural invention of a guard tower sans guard. [^]

[29] Hudson's Bay Centre Security, 22. [^]

[30] Benjamin, 427. [^]

[31] Ibid., 451. The "sandwich-man" (someone wearing poster board advertisements on their chest and back) can be seen on most busy street corners of today's urban centers. His increased territory, which is by no means limited to modern-day malls, reflects the outward explosion and dispersion of the marketplace. Today's arcades are not centralized, rather bits and pieces of them surface throughout the cityscape. In many ways, there is no outside of today's arcades or escape from their tell-tale sandwich-men. [^]

[32] Ibid., 442. [^]

[33] Ninjalicious and Culpepper, (April, 2005). [^]

[35] This section, titled "Creating Believability," appears in issue no. 6: Toronto Hotels, Luxury Leeching Dallas Style, 2. [^] [^]

[36] Benjamin, 444. [^]

[37] See issue no. 9: Paris Catacombs; Italian Subways; Scottish Rail Tunnels, and issue no. 20: Twin Cities Spectacular. [^]

[38] Ninjalicious, Tentanda Via at York University; Tunnel Running 101, Issue 4, 2. [^]

[39] Ibid., 2. [^]

[40] Benjamin, 422. [^]

[41] Ninjalicious, The University of Toronto, Issue 21, 9. [^]

[42] Ibid., 9. [^]

[43] Benjamin, 420. [^]

[44] Ninjalicious, Secret Stations; Exploring Subway and LRT Tunnels, Issue 5, 17. [^]

[45]Ibid, 17-20. [^]

[46] Michel de Certeau, Luce Giard and Pierre Mayol, L'Invention Du Quotidien : 2. Habiter, Cuisiner (Paris: Gallimard, 1994), 204.[^]

[47] Ninjalicious and Culpepper, (April, 2005). [^]

[48] The most prevalent terms are "social engineering" to describe acting, and "hacking" to describe the act of infiltration itself. For more details see the "Infilspeak" dictionary: http://www.infiltration.org/resources-infilspk.html (accessed February 5, 2009). [^]

Return to Top »