Reconstruction 9.3 (2009)

Icons and Genre: The Affordances of LiveJournal.Com / Jennifer Grouling Cover and Tim Lockridge

<1> The proliferation of Internet discourse - texts ranging from personal publishing platforms to comment-driven conversations - has led to the explosion of new genres. But will this explosion of genre also lead to the implosion of genre theory? In this paper, we seek to play with genre theory, to explore its relevance and test its limits by dealing with one particular type of online text: the blog. We ask not only what are the affordances of the blogging medium, but also what are the affordances of genre theory? What view of these texts does it offer us, and what questions are left unanswered by this look?

<2> First, we must acknowledge the definition of genre from which our analysis stems, a definition that comes not from literature or film studies but from rhetoric. Rhetorical genre theory has focused on genres not as forms but as "typified rhetorical actions" (Miller, Devitt). According to Jonathan Swales, "a genre comprises a class of communicative events, the members of which share some set of communicative purposes" (58). Thus genres are linked by rhetorical purpose rather than common form. They respond to common rhetorical exigencies to meet common rhetorical goals. In part, genres can be seen as a means to an end, a form of communication that works for a specific purpose. David Russell defines a genre as "the ongoing use of certain material tools in certain way that worked once and might work again, a typified tool-mediated response to conditions recognized by participants as recurring" (515). This shift in thinking about genre (from form to function) has proved valuable to studying texts in variety of media [1]. One such study is Miller and Shepherd's look at "Blogging as Social Action." In this 2004 study, Miller and Shepherd "characterize the generic exigence of the blog as some widely shared, recurrent need for cultivation and validation of the self." They thus link the blog as a genre to this one common exigency.

<3> While this definition seems fitting for the personal blog, it is too simplistic to cover all blogs. In fact, by 2009, Miller and Shepherd have seen such great changes to the blogging world that they reverse their previous position on blogs stating: "The blog, it seems clear now, is a technology, a medium, a constellation of affordances - and not a genre" (Questions). Within the world of blogging, there also exist different blogging platforms, and these too are "constellations of affordances." We therefore agree with Miller and Shepherd that blogs represent such vast and diverse texts that they are not, in fact, to be viewed as one genre but rather as a vessel for multiple genres. This distinction is especially evident in LiveJournal.com communities and sites, which are the focus of our study. While LiveJournals share many similarities with traditional blogs, the LiveJournal platform features a built-in social networking component that allows authors to read and write within spheres of friends and topic areas. As such, an individual LiveJournal might connect to any number of users and interests, an aspect that differentiates it from the traditional blog - and which complicates its relationship to specific genres.

<4> Within such a diverse medium, we first thought that individual blogs might serve individual purposes - that they might be examples of one genre within the larger medium of blogging. Miller and Shepherd mention examples such as the personal blog or the political blog, seemingly clear cut examples of how the blog as medium might meet different rhetorical exigencies through different genres. We identified the fandom blog as one possible genre. This particular type of blog seems especially prevalent on the LiveJournal platform, which leads us to question what specific facet of the LiveJournal service is appealing to media fans. A closer analysis, however, shows us that even self-reported fan fiction blogs on LiveJournal cover a variety of topics and respond to a variety of rhetorical exigencies. The question then becomes not only why is LiveJournal a particularly popular service among media fans, but what about this medium encourages fans to write in multiple genres and voices?

<5> It is here that the notion of affordances is particularly useful, as it seems that LiveJournal offers affordances that other blogging platforms do not. Miller and Shepherd build on Gibson's idea of affordances and redefine them as such: "An affordance, or a suite of affordances, is directional, it appeals to us, by making some form of communicative interaction possible or easy and others difficult or impossible, by leading us to engage in or to attempt certain kinds of rhetorical actions rather than others" (Questions). Affordances are features of a medium that allow for certain genres to flourish while stifling others. Hypertext, for example, affords users an ability to form links that afford a certain type of interactivity not as common in written texts.

<6> Although a more thorough analysis is required, blogs that engage with multiple genres initially seem more common on LiveJournal than of other servers, such as Blogger where users are more likely to create multiple blogs that serve different generic needs rather than keep to one blog. Thus it seems that LiveJournal offers a unique set of affordances that precipitate multi-genre blogging. One such affordance is LiveJournal's friend feature. LiveJournal's social networking features allow users to specify other users as friends and to then view all of their friends' blog postings on one page - within the space of their own blog (and without the use of an external reader). If a user creates a new blog, he/she will have to build the friend base over again. Another key feature is the use of filters. Within one blog, a user can filter posts so that only certain users on their friends list can view them. Thus, they may have a filter seen only by those they know in person and wish to share more personal stories with, or they may have a filter based on a particular interest that not all of their friends share. The notion of "friends" frames LiveJournal as a service that is "not just an online journal, but an interactive community" (Livejournal.com). Thus, LiveJournal affords a sort of interaction that is part blogging, part social networking [2]. Because of the mixed rhetorical exigency of both blogging and networking, the discourse that is afforded through the LiveJournal platform is arguably more complex than what is afforded by other blogging services. While Blogger encourages users to create different blogs for different topics and manage those blogs using their Dashboard feature, LiveJournal users create one blogging persona that is used for multiple purposes. Users can filter posts to only reach certain audiences and can post to community blogs using their same LiveJournal identity. This feature gives the user the ability to write on different topics for different audiences without starting a new blog from scratch.

<7> Seeing that LiveJournal users write in a number of different genres within the same blog, we began to wonder, how do readers of a blog recognize what genre a given post fits? The filter feature may exclude certain users to begin with, but rarely do users seem to have a filter for each genre of post. Thus, users must align what they are reading with what they have read before, drawing on prior genre knowledge to properly interpret posts. Likely there are a number of textual and visual cues to allow for this; however, we focus on another feature that is unique to LiveJournal - the use of visual icons. Other blogging technology may allow for pictures as well, but in LiveJournal these pictures are associated with each individual post, and thus, we believe, may function as signals of genre. In order to see if this is indeed how the LiveJournal icon functions, we conducted qualitative research that involved both a survey of LiveJournal users asking them about their icon use and an extensive review of one LiveJournal users' blog postings. To return to the metaphor of the microscope, we sharpen our focus to look at particular postings and icons rather than larger theoretical issues surrounding blogs. However, we do so fully anticipating that too sharp a focus may cause the slide to break.

Methods

<8> Our study looks at one of the features unique to LiveJournal, user pictures. Userpics, commonly called icons, accompany all blog posts on LiveJournal. Rather than sites like Facebook that contain one default userpic, LiveJournal gives the user a choice of icons for each post they make to their journal and for each comment they leave in their journal or others' journals. Thus, icons play a much larger role in this medium than userpics on other sites. A basic account comes with only six userpics, but paid users can have as many as 195 userpics. LiveJournal describes these pictures as, "Userpics are icons or avatars used to represent yourself, your moods or feelings, your interests, etc" (LJ). Although we take this definition as a starting ground, we believe that icons do far more than this. In order to see how these visuals are used in LiveJournal, and how they add to making it a unique space for writing, we looked both at users' own views of their icons and how one particular fan fiction blogger uses icons in conjunction with her blogging text.

<9> In order to see how bloggers themselves described their use of icons, we distributed a qualitative survey [3]. An online survey was sent via email to 125 active LiveJournal users, all of whom had posted within 48 hours and listed icons as an interest on their user information page. While this sample group may not be indicative of all LiveJournal users, it represents particularly active users. Users were asked to discuss three of their icons and how they used them as well as to comment on the selection of their default icon, which appears on their main page. Both users who are involved in fandom and those who are not were represented in the sample; however, 74% of the participants had at least one icon that was associated with a fandom. This number furthers our intuition that LiveJournal is a particularly popular service for members of fandom communities. From the 23 users that responded to the survey, a corpus of 88 icons was compiled [4]. These icons were coded based on four purposes, noting that icons could fit more than one category. These purposes - to identify the user and portray a positive self-image, to add to the emotional content of one's textual post, to associate oneself with a particular fandom, interest or hobby, and to associate oneself with a specific user or community - coincide with LiveJournal's own description of the purpose of LiveJournal icons.

<10> To better consider the connection between icons and content, we have explored the ways in which one LiveJournal user applies icons to her posts. Celli, a prominent fan fiction author and member of many fandoms, is an ideal candidate for this sort of study [5]. Her LiveJournal, like those of many media fans, houses multiple genres of blog postings, ranging from the highly personal to direct addresses to her fan communities. One year's worth of Celli's LiveJournal archives showed posts on a variety of topics including Community, Current Events, Fan Fiction, Fandom, Links, Personal, Professional, and Writing. We applied the same four-point coding scheme from the survey to Celli's icons but also analyzed the way in which the textual content of her posts worked with the visual icon. A ninety-minute phone interview from Tim's previous study with Celli provided additional data. The combination of these two data sets allowed us to complete a more thorough analysis.

Brief Histories: Blogging and Media Fandom

<11> Before detailing our own study of LiveJournal, it is useful to provide a brief background on blogging, in general, and for media fandom, in which many of the LiveJournal blogs participate. While web pages have, since the medium's inception, served as a means of indexing and transmitting content, the blog (a contraction of "web" and "log") and the advent of GUI-driven blog publishing platforms presented users with a means of filtering and presenting web content with little technical knowledge required. This statement, of course, is now a well-known one. In its "State of the Blogosphere 2008" report, web indexing service Technorati notes that "there have been a number of studies aimed at understanding the size of the blogosphere, yielding widely disparate estimates of both the number of blogs and blog readership. All studies agree, however, that blogs are a global phenomenon that has hit the mainstream."

<12> The global phenomenon of blogging is largely the product of a movement initially fostered by two major platforms: Blogger and LiveJournal. Blogger, founded in 1999 and now owned by Google, best represents the blog's accepted contemporary form, something Technorati defines as "a web site, usually maintained by an individual with regular entries of commentary, descriptions of events, or other material such as graphics or video. Entries are commonly displayed in reverse-chronological order." The Blogger platform also represents the manic nature of the medium, a space where one user can create and maintain blogs driven by personal anecdotes as well as sports blogs, political blogs, and celebrity blogs. In a sense, blogs have become as ubiquitous and diverse as their print-driven ancestors.

<13> LiveJournal, publicly introduced only months before Blogger, shares the same defining characteristics, offering users a simple interface with which to generate content and then publish and archive that content in a reverse-chronological order. Moving beyond the collection of content, however, LiveJournal also allows users to build a social network, connecting with "friends" and participating with like-minded communities. These features have driven fan communities - populations that once relied on newsgroups and mailing lists - to the LiveJournal platform en masse. One feature that LiveJournal offers is community blogs, where individual users can all post on a similar topic. For example, the "doctorwho" community, a LiveJournal group dedicated to "stuff to do with Doctor Who, Torchwood, and Sarah Jane Adventures," boasts 6,072 members. Likewise, LiveJournal's largest Harry Potter fan community includes 8,549 members. In contrast, while there are surely thousands of fan blogs on the Blogger platform, Blogger offers no way to identify these communities - or link their users. Without the friends feature of LiveJournal, one cannot see how many users watch any given blog or community. In an otherwise crowded blogosphere, LiveJournal's community features have facilitated the varied interactions of numerous media fans and "fandoms."<14> Blogs, as we look at them here, have a rather adversarial relationship with the mainstream perception of popular culture, and this relationship may explain their popularity in the world of fandom. In their explanation for the popularity of blogging, Miller and Shepherd state that a main rhetorical exigency for blogs is the growing "dissatisfaction with the mainstream media" (Questions). In part, this answers the question of why fandom has migrated to blogs. Henry Jenkins' Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, the first major academic exploration of "fandoms" and fan practices, focuses on the ways in which fan communities subvert cultural hierarchies and engage with mass media. Jenkins notes that,

The stereotypical conception of the fan, while not without a limited factual basis, amounts to a projection of anxieties about the violation of dominant cultural hierarchies. The fan's transgression of bourgeois taste and disruption of dominant cultural hierarchies insures that their preferences are seen as abnormal and threatening by those who have a vested interest in the maintenance of these standards. [...] Fan cultures muddy these boundaries, treating popular texts as if they merited the same degree and attention as canonical texts. Reading practices (close scrutiny, elaborate exegesis, repeated and prolonged rereading, etc.) acceptable in confronting a work of 'serious merit' seem perversely misapplied to the more 'disposable' texts of mass culture. Fans speak of 'artists' where others can see only commercial hacks, of transcendent meanings where others find only banalities, of 'quality and innovation' where others only see formula and convention. (17)

<15> An exploration of the texts produced by fandom subcultures can help us understand the prevalence of fandom communities on blogs such as LiveJournal. Fan fiction, a major textual focus of many fandom communities, responds most clearly to dissatisfaction with popular media and culture; for example, fanfiction writers often write new stories about characters in popular television shows that respond to the lack of representation of alternate sexualities in mainstream television. In an interview, Celli notes that "the show has to have certain characteristics to draw people in. It doesn't have to be good. In fact, a lot of good shows don't have a big fanfic community. Because if you're getting everything in the show, why do you need to write anything? Often what you need for a big fanfic community is a very badly flawed show with interesting characters." Fan fiction, in this regard, is an attempt to reclaim and extend popular contemporary narratives.

<16> But fan fiction also functions in capacities beyond those of simple narrative extension. "Slash," a subset of fan fiction that Jenkins, in Textual Poachers, argues "may be fandom's most original contribution to the field of popular literature," is perhaps the most tangible example of fandom's dissatisfaction with and rewriting of popular television narratives (188). Slash stories pair two of a television show's male protagonists in a romantic - and often erotic - relationship. Jenkins defines the major premises of slash as "the movement from male homosocial desire to a direct expression of homoerotic passion, the exploration of alternatives to traditional masculinity, the insertion of sexuality into a larger social context" (186). While fan fiction might be hastily perceived as the simple extension of television narratives, slash stories find fans engaged in an act of rewriting - subverting and challenging accepted norms. Jenkins writes,

Slash stories center on the relationships between male program characters, the obstacles they must overcome to achieve intimacy, the rewards they find in each other's arms. Slash represents a reaction against the construction of male sexuality on television and in pornography; slash invites us to imagine something akin to the liberating transgression of gender hierarchy John Stoltenberg describes - a refusal of fixed-object choices in favor of fluidity of erotic identification, a refusal of predetermined gender characteristics in favor of a play with androgynous possibility. There are considerable implications behind shifting our conception of male heroes, since a fairly rigidly defined and hierarchical conception of gender remains central to all aspects of contemporary social and cultural experience. (189)While not all fans participate in either fan fiction or slash writing, slash acts as a reminder of the work that occurs in some fan communities. Fans aren't simply discussing dialog or plot points; fandom, as a whole, represents a dynamic and challenging mix of communicative and textual practices.

<17> In the time since Textual Poachers, Jenkins has extended these theories to address the growing fan and fan fiction communities facilitated by access to new media technologies. Other scholars have also commented on the way fandom has changed as it has gained popularity online. In his look at music fandom, Theberger argues that with the move to online forums, "fan clubs become more than simple, isolated groups of individuals with a particularly strong attachment to an individual celebrity or media text" (486). Instead, he posits that fandom leads more directly to social action by creating a bridge between fans and artists. While Theberger focuses only on music fans, several prominent examples suggest that the move to online communities has worked to break this divide for other fans as well. When the show Jericho was slotted to be canceled, online fans gathered together to send over 20 tons of peanuts (a joke in the show) to the studio, which resulted in CBS making another season of the show (Nuts). In addition, celebrities such as Will Wheaton of Star Trek: The Next Generation fame have themselves started blogs that are read and discussed by larger fandom communities. Thus blogging (and online discourse in general) has afforded shifts in the interactions that are available to members of media fandom.

<18> While we acknowledge that "fandom" as a collective is as amorphous and ill-defined as the "blogosphere," we argue that LiveJournal's unique social features (friend lists, user and post icons, community memberships, etc) have drawn fan communities away from both antecedent and competing technologies. Celli notes that, while she first found fan fiction writers on a listserv in the early nineties, "[LiveJournal] was the preeminent place for people I knew. Even if I saw your fic on a website or a mailing list somewhere, you probably had a LiveJournal. [. . .] There was a big migration from mailing lists to LiveJournals, and there hasn't been that migration elsewhere yet."

<19> Members of LiveJournal fan communities engage in both social and individual practices, rendering their individual LiveJournals a complex mesh of genres and interactions. Our following study seeks to explore user icons, one of the affordances of LiveJournal that make it a particularly rich landscape for fandom. User icons are a key component of LiveJournal, facilitating multiple genres of posting within the space of an individual LiveJournal. As such, fan blogs become a tangle of fandom-driven conversations, personal narratives, and writing workshops. LiveJournal then allows fans to move beyond the topic-centric threaded discussions of message boards and newsgroups, instead representing participation in fandom as another facet of everyday life.

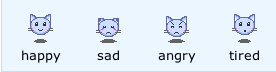

Icons as Self Representation

<20> It is interesting to note that although the official term for the pictures associated with LiveJournal is "userpic," the common term that bloggers use for these pictures is "icons." While it might seem that these pictures are always a representation of the blogger, the switch in terminology here is significant to understanding the way that users see their own icon use. In his study of LiveJournal, Kurt Lindemann claims that icons can serve as "a bodily presence" in these online communities. While we believe this is true, we also argue that icon use is far more complex than the embodiment of self.

|

<21> While not all icons are representative of the self, specific kinds of icons do more directly embody the user in this online space. One possible reason for using icons that represent the self may be to signal more personal posts as opposed to posts that talk about fandom or less personal issues, and this can be achieved through an actual picture of the user. Often these pictures serve as default icons for a specific LiveJournal. The default icon is somewhat different from other icons since this is the picture that appears on the users profile page. This icon also appears any time the user posts and does not select a different icon to represent the post. For example, user Isiscaughey states, "My default icon is actually a picture of me (instead of the fandom icons I usually use). I wanted a real picture to represent myself, and show how I actually look. I don't use it that often when posting, but it's the one on my info page that everyone can see." It is clear that for her the default icon serves to signify herself in this online world - rather than to add to the content of specific blog postings. In addition to actual photographs, bloggers may choose more abstract images to represent themselves. FireyIrishAngel is quite fond of her icon shown here:

|

She explains,"As a woman with dark hair, engaged to a man with red hair, who have a baby together, I'm fond of this piece (by Kurt Halsey). My family is the center of my world, no matter what my other interests may be, and I feel that they are the best representation of who I am." This icon also serves as a default for FireyIrishAngel's journal.

<22> Another key affordance of LiveJournal is the username. While Blogger and other common webservers may have a title for the blog, users on LiveJournal create online personas and often refer to each other by these names, both online and off-line. Therefore, another way of representing oneself is through icons that add text with the username on them.

|

<23> One of Celli's most frequently used icons shows a picture of Kermit the Frog coupled with the words "Celli- Flaiiiiiiil!" and acts as both a representation of self and a display of emotion. The inclusion of Celli's user name (coupled with the dash) in the icon presents an element of personalization and a command for Celli to engage in a flailing, highly-exaggerated form of excitement. The suggestion of a physical response is heightened by the drawn-out set of i's in flail as well as the comic mannerisms suggested by Kermit the Frog. Another of Celli's icons mentions flailing,

|

but here the suggestion of movement is subdued, understated in a text-only icon. This icon lacks the specifics of personalization and the visual, emotional attachment connected to character, and, as such, is infrequently used.

Icons as Emotional Appeals

|

<24> While self-representations, particularly photographs, may embody the user to some extent, Hartelius argues that members of online communities identify with each other most closely based on emotions rather than embodied interactions (74), and many LiveJournal bloggers use icons to convey particular emotions. This usage may initially seem redundant, as the LiveJournal platform offers pre-defined "mood themes" emoticons (like Neko's Kao Kitties, pictured above) which users can apply to specific posts. Why then do users add custom icons to help establish the mood of their posts? For one, these icons are more personal and detailed. While every post may have a generic emoticon in the box, posts with emotional icons may signal a specific, emotion-filled entry. Celli's icon for stress, for example,

|

is a stark set of dice-like letters laid against wood grain. While the background suggests a desk, the lighting source adds a long shadow to the letters, giving the small blocks a long, imposing feel. This visual offers a stronger representation of stress than a simple emoticon.

The same can be said for Celli's icon for exhaustion, which finds Jim Davis's Garfield character face down and asleep, barely beyond the front door. While this icon might connect Celli to fans of Garfield, it serves the same primary function as the stress icon - adding visual subtext to a post. When describing a long day at work in a personal post, for example, the exhausted icon adds a level of meaning. Connected to the discussion of a new episode of American Idol, however, the icon also adds meaning - but in an entirely different manner.

|

<25> While these icons do depict emotion - stress, exhaustion, joy - they often serve another function. Some of these icons relate to fandoms. AmiKara, a blogger who explains that her journal is primarily "fannish" has a series of Stargate Atlantis icons depicting different emotion. For example, the "Wrath" icon above both depicts anger and connects AmiKara with other Stargate Atlantis fans.

|

Icons as Hobbies and Fandoms

|

<26> Of the four categories for our survey results, we found that conveying a particular emotion or relating to a particular fandom, interest or hobby, were the most common uses of icons. For example, Daniemeg uses the following icon to show her interest in baking. While this image is fairly basic, it establishes one of Daniemeg's favorite hobbies and connects to her posts about baking.

<27> Another affordance of LiveJournal is that

in additional

to individual blogs, there are numerous community blogs. In order to

post in these forums, users simply join the community. When they go to

make a posting, they then have a choice of whether to post to their own

personal journal or to the community journal. The username and icons

they create also identify them on these community blogs.

<28> Making icons is itself a popular hobby, and one that

has

spawned numerous LiveJournal community blogs. One such community,

simply called "icons," boasts 7,192 members. In particular, fans often

create communities for the purpose of making, distributing, and

evaluating icons. Many communities are based on making icons for a

particular fandom - for example, three are devoted solely to "Harry

Potter" icons. User HaleySings says she is particularly proud of one of

her icons because it won first place in a contest in the Princess Tutu

(an anime film) communities icontest. This icons signals both

HaleySings interest in anime and her interest in icon-making as a hobby.

|

Icons as Community Identification

<29> Our final category for userpics, those that are used to identify with a particular community, speak even more to the communal nature of LiveJournal. When users post to community blogs, they post with their individual usernames and the icons they have as a part of their individual journal. Often, then, users create icons that are intended for use on certain community blogs rather than their personal journals. Hartelius's taxonomy of blogs separates group blogs as being topic-oriented whereas personal blogs are focused on the individual (88). It follows that icons created for community blogs might then be particularly topic-based rather than emotion-based.

|

<30> One survey respondent commented that a particular icon, pictured below, was used mainly in certain communities. This user states, "I use it mainly when replying to sextips, bad_sex, or any other entry that talks about genitalia gone wrong." Like icons in the last category, this one depicts a scene from a particular television show, House, but rather than using this icon to simply show her interest in that fandom, she uses it to post in topic-based communities. Sextips and bad_sex are both communities that revolve around discussion of sexual activities and not around fandom per se.

<31> Another type of icon that we

place in this

category are icons that may not reference a specific LiveJournal

community blog, but are so detailed in their allusions that they are

clearly meant only for a small portion of a personal blog's readers.

The level of nuance and insider information is particularly noticeable

in Celli's "Slash Goggles" icon: As a significant portion of Celli's

fan fiction work centers on slash stories, she has multiple icons

connected to specific slash fandoms. The above icon, however, is

perhaps the most subtle. Through a black-and-white photo, primary color

scheme, stylized use of fonts, and advertised price of thirty-five

cents, the icon initially appears to be a vintage ad for "splash

goggles." Upon closer investigation, however, the icon actually says

"slash goggles" - a term frequently used in slash fan fiction

communities. (One fan fiction author who blogs at slashgoggles.com

defines the term as "invisible goggles that let the wearer see

homoerotic subtext everywhere.") This depiction of "slash goggles,"

then, is a codeword of sorts, a nod to and alignment with a particular

subculture that will be missed by a reader unfamiliar with the lexicon

of slash fiction communities.

<32> In

almost all of its uses, however, Celli's "slash goggles" icon is

coupled with posts that candidly discuss the homosexual/erotic

relationships of characters. In a post titled "Things that make me

blush," Celli writes, "I'm reading a bit from a fic a friend sent me,

and it's really *good* threesome smut, I assume, but I've been trying

to read it all night and I'm still stuck on the kissing in the

beginning because I'm blushing too hard to read it!" That same day, in

a post titled "Verbotene Liebe: German for 'the hottest boykissing

you'll see outside of niche cable channels,'" Celli discusses brief

"ficlets" based on a german soap opera, the titles of which include

"HALP INTARWEBS. A BOY KISSED ME. IS I GAY?", "no worries, i'm sure

you'll grow a set of balls later", and "HELLO SHOWER MOMENT". A third

use of the slash goggles icon occurs in a post titled "zomg slash!",

where she writes "I still haven't gotten over the delight of seeing a

healthy, established queer relationship on my television screen, and

this was a really great relationship (did I mention Timothy is

ADORABLE) and an interesting mystery." Again, nearly every use of the

"slash goggles" icon is coupled with text that candidly describes

slash-related subject matter.

<33> Celli has a number of additional icons that display two male characters from her various fandoms engaging in varying degrees of intimacy:

|

These icons, however, are often connected to posts about the specific fandoms represented by the characters in the icon - providing a visual slash-based subtext to an often content-based discussion of plot, characters, or actors. In some of her most candidly "slash" posts, however, Celli routinely chooses to use an icon that operates on subtlety and insider knowledge. The fact that these slash icons are particularly tied to posts about slash fandom leads us to believe that these icons are used to indicate the genre of the post they accompany.

Icons as Indicators of Genre

<34> While our four categories of icon use (to represent the user, to convey an emotion, to associate with a particular hobby or interest, and to associate with a particular community) capture many of the reasons why LiveJournal users add icons to their posts, these categories are not necessarily to be taken as analogous with genres of postings. After coding icons based on these categories, we still found ourselves questioning what exactly this affordance of LiveJournal gives to users. In this section, we test our hypothesis that icons are signifiers of genres.

<35> Since default icons appear on the main user page, it might seem that they would signal the genre of the entire blog. At times this seems true. AmiKara states that for her default icons she uses "mostly a picture from the show/movie/whatever which is, as I call it, my 'main fandom.' And since my lj (sic) has turned more into my fannish and less into my private journal, I feel it's appropriate to use a picture other than me or things from my personal life as my default picture." Her default icon at the time of the survey is seen here.

|

Unlike Isiscaughey's default (shown in the section on self-representation) that was an actual photograph of her, this icon does not represent AmiKara in terms of her own identity, but in terms of labeling her journal as a journal dedicated to fandom.

<36> Similarly, SarahRose has a default icon from Titanic, which she says is "my ultimate fandom."

|

Thus,

one might conclude that some users signify the genre of their blog, in

part, through their default userpic. However, this statement does not,

in fact, hold true upon further exploration. Isiscaughey's personal

icon actively resists her own definition of her blog as

"fannish." While AmiKara and SarahRose's default icons

appear to

signal to other users what their main fandoms are and thus draw

connections between themselves and other members of that fandom, it is

interesting to note that SarahRose's journal does not seem particularly

geared toward fandom. A quick glance at her most recent public entries

shows a poll about what color of iPod she should buy, a post about her

travel to Florida, and pictures of her most recent polymer clay work.

While a self-proclaimed huge fan of Titanic, SarahRose does not list

fandom or fan fiction as an interest on her userpage, and does not

appear to list any fandoms besides Titanic. It therefore seems

incorrect to label her blog as a "fannish" or "fandom" blog.

<37> We restate, then, that individual blogs on LiveJournal do not represent genres, but are multi-genre texts. The trend that we see emerging is that even when a blog has a stated purpose, such as Isiscaughey's "fannish" blog, individual posts often represent different genres. In order to further explore this theory, we offer some in-dept analysis of Celli's icons in relation to the textual post they accompany, something that the survey of bloggers was not able to show. Carolyn Miller argues that "a rhetorically sound definition of genre must be centered not on the substance or the form of discourse but on the action it is used to accomplish" (151). The following uses of icons from Celli's LiveJournal show how each icon links with a certain type of response.

|

<38> The use of specific fan and fandom icons presents a nuanced and potentially haphazard mode of visual communication. This icon, a picture of political commentator Rachel Maddow, is used in two posts of fan fiction which feature Rachel Maddow. These are both short narratives - fictionalized vignettes featuring Maddow as a central character. In this use, the icon illustrates the post's (or story's) main subject matter. However, in another post containing only an observation - "RACHEL IS TALKING ABOUT MY TAXES ON TV" - rather than a piece of fan fiction, Celli uses the same icon. The same icon is then used again in another post which briefly recounts Maddow's appearance on an episode of The Colbert Report. While this sort of icon use initially appears haphazard, it becomes more calculated in light of the following icon, which is also a depiction in Maddow. In this icon, Maddow, who is casually dressed, wearing headphones, and talking into a microphone, is presented as a radio personality rather than a television host. (Maddow has a radio program on Air America Radio and a television show on MSNBC.) In her first use of this icon, Celli says that she is, among other things, "listening to old Rachel Maddow radio shows." In her second use of this icon, Celli writes that "...Rachel talked about NASCAR." Thus, between the two icons, Celli has addressed two spectrums of the same fandom. As the first icon is used specifically for visual(ized) representations of Maddow (fiction and specific TV appearances) and the second icon is used solely for audio representations, the two icons show both a heightened level of authorial awareness in icon selection and strong connection between textual post content and visual icon cues. Furthermore, these icons represent two different genres that Celli is responding to - the first being Maddow's TV show and the second being Maddow's radio show.

|

<39> Icons don't, however, have to connect to a specific subject or fandom to signify genre. In a post asking readers "What would your ideal Sci-Fi movie be?" the icon is an animated typewriter taken from the children's show Sesame Street, which bears no specific connection to either science fiction, fandom, or film. The icon offers a sort of visual imperative to the post, implying that the author's question is more a writing prompt than a casual aside or conversation starter. As the LiveJournals of fan fiction writers house a variety of blog genres, this icon use asks users for a certain type of response. The icon then not only signals the genre of the post - writing prompt - but cues readers as to the proper way to respond to the post.

Conclusions, Limitations, and Implications

<40> The data we have presented here builds on the previous work of both genre studies and cultural studies. As Miller and Shepherd note, "with a rapidity equal to that of their initial adoption, blogs seemingly became not a single discursive phenomenon but a multiplicy" (Questions). Our study has suggested that this multiplicity exists not only across blogs but within individual blogs on LiveJournal.com. As such, the concept of genre becomes increasingly problematic. Miller and Shepherd ask: "what is it that can be reproduced sufficiently to create genre identity in varying instantiations?" (Questions). One answer, within the context of this study, is that the LiveJournal user icon is reproduced to the point where it serves as one signal of a genre within the larger medium of the blog.

<41> Yet this conclusion is not completely warranted, nor is it completely satisfying. We asked LiveJournal users their intentions behind their use of visual icons, but we did not ask readers of each blog to comment on how they saw icons being used or whether these visuals helped them distinguish between different types of posts. If we view genres as part of larger activity systems, as David Russell does, then even the same text can function as different genres depending on the audience. Russell's example is that Hamlet can be a script for an actor, or a play to be watched by an audience, or a text to be studied by a Shakespearean scholar (518). Similarly when we look at any given blog, there are a variety of users who read for different purposes. Celli's "friends" list contains people she knows in "real life," people who she knows only online, and people who may or may not be a part of the various fandoms she participates in. In addition, there is no way to know which individuals outside of her friends list may read Celli's publicly available posts. Online texts make this sort of audience analysis particularly problematic. Although the comments left in blogs may add some insight into the readers of a particular blog, there is no real way to capture the many different ways a blog can be read. As such, any taxonomy of blogging genres is inherently limited. Even if such an analysis were possible, when we focus our view on individuals reading blogs with their individual view and interpretation of each post, the concept of genre begins to fail us.

<42> Some of this failure is due to the nature of online texts. Rhetorical genre theory is easier applied to texts with a known audience. We can study who physically attends a speech and what actions they are persuaded to take as a result of the speech. Perhaps, we can more easily say that a speech meets a certain rhetorical exigency - that it's a campaign speech or a eulogy, and that those meet distinct rhetorical needs. But can we say the same of blog postings? Does the concept of genre afford us the ability to analyze texts that are so variable, so heterogeneous in nature? Miller's early (1984) work on "Genre as Social Action" makes it clear that not every kind of text can be considered a genre, a concept that seems somewhat lost in current genre study. Furthermore, she asserts that "to say a genre does not exist is not to imply that there are no interpretive rules" (164). At this point, we remain agnostic as to whether or not genres within an individual blog can be identified and if there is a value in attempting to do so. Clearly, there is an interpretive frame at work, as our analysis of icons shows, but whether or not this is a generic interpretive frame remains to be seen. Tracing the use of several icons for a longer period of time as well as the responses given to posts with those icons would offer further insight into if icons always serve as generic markers and is one possible area for further research.

<43> Future studies may also wish to do a more detailed comparative analysis of different blogging platforms. For example, it would be telling to compare a fan fiction blogger on LiveJournal and a fan fiction blogger who posts using Blogger, TypePad or another service. Our study suggests that the addition of visual icons in particular adds a great deal of meaning to individual posts. To further understand the way that discourse is affected by the features of each individual technological platform, a more detailed analysis is warranted.

<44> Finally, the critical role of technology in cultural discourse should also serve as a call for continued research and scholarship. The ties between fandom and new media are reciprocal: Just as emerging technologies have allowed for significant growth in fan communities, fans have stretched and appropriated nearly every facet of those technologies. Fan communities engage in nuanced and complex forms of discourse, using both underground and mainstream media to challenge norms and subvert accepted hierarchies. In our continued study of genre online, we must not forget that genres are ultimately rhetorical constructs grounded in larger cultural trends. It may ultimately be in this connection to larger cultural communities with larger social exigencies that genre theory proves most useful to our study of online texts.

Works Cited

boyd, danah and Nicole B. Ellison. "Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship." Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13.1 (2007). 10 Dec 2008 <http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol13/issue1/boyd.ellison.html>.

Devitt, Amy J. Writing Genres. Southern Illinois University Press, 2008.

Hartelius, E. Johanna. "A Content-Based Taxonomy of Blogs and the Formation of a Virtual Community." Kaleidoscope, 4 (2005): 71-91.

Jenkins, Henry. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Lindemann, K. "Live(s) online: Narrative performance, presence, and community in LiveJournal.com." Text and Performance Quarterly, 25 (2005): 354-372.

LiveJournal FAQ. http://www.livejournal.com/support/faq.bml

Miller, Carolyn R. "Genre as Social Action." Quarterly Journal of Speech 70 (1984): 151-167.

Miller, Carolyn R. and Dawn Shepherd. "Blogging as Social Action: A Genre Analysis of the Weblog." Into The Blogosphere. eds. Laura Gurak, Smiljana Antonijevic, Laurie Johnson, Clancy Ratliff, Jessica Reyman, 2004. 22 October 2004. http://blog.lib.umn.edu/blogosphere/blogging_as_social_action_pf.html.

---. (in press) "Questions for Genre Theory from the Blogosphere." Theories of Genre and Their Application to Internet Communication. ed. Janet Giltrow and Dieter Stein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing (2009).

Nuts! Jericho Saved. Accessed 19 Dec. 2008. http://www.nutsonline.com/jericho.

Russell, David. "Rethinking Genre in School and Society: An Activity Theory Analysis." Written Communication 14.4 (1997): 504-555

Swales, John M. Genre Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

"Technorati: State of the Blogosphere 2008." Technorati. 08 Dec 2008 <http://technorati.com/blogging/state-of-the-blogosphere/>.

Théberge. Paul. "Everyday Fandom: Fan Clubs, Blogging, and the Quotidian Rhythms of the Internet." Canadian Journal of Communication, 30.4 (2005): 485-502.

Notes

[1] This is a somewhat simplified version of the shift in genre theory. Form continues to play a role in genre analysis; however, it is no longer seen as the primary means of distinguishing one genre from another. [^]

[2] In "Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship," Boyd and Ellison define a social network site as "web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. The nature and nomenclature of these connections may vary from site to site." [^]

[3] Our collaboration on this project began by combining two previously collected data sets. Jennifer conducted the initial survey in the Spring of 2007, while Tim interviewed Celli in Fall 2008. Here we combined and re-framed both sets of data in order to focus on the role of user icons and genre. [^]

[4] Although the response rate for the survey was somewhat low, we believe that the qualitative nature of the questions still led to a rich data set. One reason for the low response rate may have been from spam filters deleting the original email with the survey link, a danger inherent in this method of solicitation. [^]

[5] One question on the survey asked users whether or not they wanted us to include their user name. Only one user chose to remain anonymous. Likewise, we only analyzed Celli's already public postings. However, since many users give credit to other users for making icons for them, issues of ownership become problematic when dealing with these visual images. [^]

Return to Top»