Reconstruction 10.3 (2010)

Return to Contents»

|

Photo by: Kamran Ashtary: Creative Commons license, some rights reserved. |

Activism and Preserving Complexity; How Iranians Turned Me Into an Activist / Tori Egherman

<1> Iran is amazingly and gloriously complex. I was part of the complexity. An American. A Jew. A Midwesterner, even. Married to an Iranian who was a Dutch citizen. If I was possible, anything was possible. When I lived there, I could reconcile the closed and oppressive regime that imposed itself upon a society that included the outspoken and friendly strangers, friends, and family that I encountered daily. I could easily traverse a world that included observant Muslims who served their less observant guests good alcohol, nostalgic shopkeepers who hung paintings of Iran’s supreme leaders on the wall while keeping photos of the former shah hidden under the counter, and non-believers with childhood friends who fought with the Hezbollah in Lebanon. It’s easy to forget how diverse and surprising Iran can be from outside the country. “Even when you are not in the country for just five years there are things you do not understand anymore,” says former Reformist parliamentarian Fatimeh Haghighatjoo.

<2> Former vice president Ali Abtahi, who was arrested shortly after the June elections, felt that the time was much shorter, telling a journalist, “I’ve been out of the country for a week and don’t know what’s happening.” [1] I’ve been out for almost three years and have already begun to lose the narrative thread. I've forgotten how easy it was to hide demonstrations, even large ones, in the chaos that is Tehran. I've forgotten how easy it was to disbelieve everyone when surrounded by so many lies and the insipid seduction of faulty logic.

The Big Lie

<3> The big lie seduces. The Iranian regime has mastered that lie. They build it logically in order to attract intellectuals and communicate the lies emotionally to entice the less educated. “Sometimes when I just read what Ahmadinejad and his supporters say – and you know I do not like him at all, but I just read it, and I don’t think who it is coming from – I think, they are right. Why shouldn’t someone stand up to the West? There is some logic to that,” an Iranian scientist said. She went on to report that a friend of hers was starting to believe Neda [2] was killed by one of us. He supports the opposition movement in Iran but lives in the college dorms and does not have access to satellite, so watches only state-controlled television. “You don't know,” she said. “They show the images so many times, and they make a really convincing argument.”

<4> So I wonder, am I telling myself a big lie? Have I purposely simplified the complexity that is Iran so that I could support a movement that may or may not be one that is supportive of civil and human rights? Have I reduced the supporters of the regime to caricatures? Worse, have I been swept away?

#iranelection

<5> In June 2009, I became activated. That’s how I think of it, at least. While I have always been prone to superlatives and exaggeration, I have never been prone to activism. In fact, a week before the 2009 presidential elections in Iran, I was enjoying a warm evening in Amsterdam with a writer friend and my husband, Kamran. We were sitting outside a café, drinking brandy to celebrate an unusually busy year for the journalist friend. I was complaining about work and the lack of work, complaining because it is the one competitive sport at which I excel. “I hate activists,” I said. Remember, I wrote that I am prone to exaggeration; I don’t actually hate activists. Kamran and our writer friend looked at me with shock. “How can you say that, when I have dedicated my life to activism?” She had done amazing work helping journalists in and from closed societies communicate their stories. “Not you. Of course I don’t hate you. I just hate the whole lack of nuance that comes with activism. I live in the grey area,” I said. “I am a moderate, what can I say?” I’m a moderate who speaks in extremes.

<6> By that time Kamran and I were involved in the campaigning in Iran. Many inside and outside Iran felt that their failure to participate in the 2005 elections helped to usher in the presidency of hardliner, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. They were determined to take part. They wore green to signify support for the decidedly uncharismatic candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi. Other candidates followed suit, asking supporters to wear red or white. But it was the green that captured the imagination of so many in Iran. And it was the green that came to represent a wider call for civil and human rights.

<7> At the beginning of the official campaign season a little more than a month before the elections, no one expected Mousavi to win. People expected a run-off election, but not a landslide for any of the candidates. The government bragged that it would have the most closely watched and honest election in its history. It allowed shockingly frank debates between the candidates on state-run television. The streets of cities all over Iran began to fill up with people taking advantage of the lax enforcement of restrictions during campaign season in order to discuss politics and social matters, fraternize with the opposite sex, and show their support for change.

<8> The State, with a capital S, lost control of the message. The message was constructed and shared on the streets where people were gathering for discussion and on the Internet where people with a lot to lose were ranting against the regime. When the State failed to issue permits for Mousavi rallies, text messages brought hundreds of thousands on to the streets. When cell phones were blocked, people whispered to one another. A 27 year-old teacher in Tehran reports, “People were talking to each other about the economy and the bad international situation, not about the candidates themselves. This gave me a good feeling. It was great. People from the south of Tehran came to Vali Asr crossing and expressed their own problems.”

<9> A few days after drinking brandy with our friend, Kamran and I were following the election results in Iran. We got a call from a friend who reported on the ballot count in one of Iran’s largest cities. “You can’t believe it,” he told us. “My source says that 70% of Ahwaz’s votes have gone to Mousavi.” Kamran started making website banners that read, “We did it.” Only, guess what, the next thing we heard, the results from that same city were exactly opposite: 70% for Ahmadinejad. Kamran slammed his head against the table. “What is happening?” he asked. “What is happening?” Phonelines were down. The Internet was cut.

<10> We watched the iranelection (#iranelection) search tag (hashtag) on Twitter go from being dominated by a couple of people we knew (virtually and physically) – pro-Mousavi computer geeks in Tehran, Mideastyouth.com bloggers, a couple of journalists, and a supporter of Ahmadinejad – to a buzz of tweeters we had never heard of: oxfordgirl, stopahmadi, iranriggedelect, Persiankiwi...

Activation

<11> On June 15th, the Monday after the elections, three million Iranians in Tehran took to the street: quietly, tentatively, with amazing courage. “Believe me,” a photographer told me, “you have never seen anything like it. You have never seen a people more civilized, more proud, more peaceful. Believe me, you have never seen it.”

<12> By July, I had gone to demonstrations in front of Iran’s embassy in The Hague, in front of the Dutch Parliament, in Amsterdam, and was working night and day to help organize United4Iran’s global day of action. I was activated. I had become an activist. It was not a choice. It was a compulsion. I knew what kind of courage it took for people to dissent in Iran. After attending a demonstration to protest a sermon by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamanei in which he completely disregarded the demands of protesters, [3] a friend in Iran wrote to me:

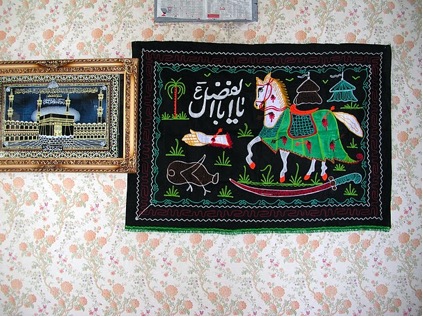

At 3:30 we set off on the way to Revolution Square [downtown Tehran]. In the streets, it’s war. The streets are full of security forces in plain clothes with batons in their hands and helmets on their heads. In their other hand they carry shields. They are armed to the teeth. In their gaze is contempt and a greedy leering. Oh God, This is Iran. Where are we? Maybe we are sleeping. Maybe we are dreaming.

I pinch myself to see if I am awake. Yes I am awake. This is true. In my Iran, we have become slaves. In my Iran, our shouts have been stifled in our throats. Oh God, we ask you for refuge. Nobody and nothing can help us. So you help us God.

I arrive at Vali Asr Square. The martial presence is much more visible here. Why are all these special forces in their black uniforms and their weapons here? The people donÕt have any weapons. We are unarmed. But of course, we have the most powerful weapon of all: our silence. Now I understand that silence is full of what is unsaid. Silence is a universe of words. Silence is shouting. Shouting. Shouting.All the streets going to Revolution Square are closed. The special forces (the black uniformed) with their heavy motorcycles are parading up the street. The closer we come to Enghelab, the more armed plain clothes forces and anti-riot police we see. No matter which direction you take, they say Where are you going? Get Away! You ***!

With their greedy leers and their uniforms, they proudly display their power.

<14> How could I remain unmoved? Inactive? I was obliged to act. I was driven by the actions of friends and family, strangers, young and old. I was compelled by arguments that included rights for women and for minorities, peace, and democracy.

Good and Evil

<15> In the process, I turned the Green Movement and the supporters of the regime into caricatures of good and evil. I ignored the anti-Semitism [4] of many who had found a home under the Green umbrella of opposition and that was most obvious when Ahmadinejad was accused of coming from a family with Jewish roots [5]. I joined others in constructing a narrative that simplified Iran’s multifaceted society and led inevitably to mass acceptance of change. There were stories of Ahmadinejad supporters who deplored the violence used against peaceful protesters. I heard of one supporter accidentally arrested and then dumped with others in the desert southwest of Tehran. Still others remained steadfast, including people who absolutely refused to acknowledge any homegrown dissent at all in Iranian society. A young woman from an observant and politically conservative family sent her parents films of the demonstrations in Iran to try to shake their faith in the regime. “Why do they go out on the streets,” her mother asked when she watched the videos, “if they know they will be beaten?”

The Basij: Paramilitary Volunteers

<16> And what of the Basij? Iran’s paramilitary youth movement? They are blamed for much of the violence against demonstrators including the murder of Neda Agha-Soltan. It is easy to simplify them, as so many inside and outside Iran do: to turn members of the Basij into automatons, brainwashed bullies without sense or smarts, to forget that before the election, many of them were openly in favor of opposition candidates and that some of them long for a more democratic Iran as well. The Basiji wear black and white checked kaffiyas, ride motorbikes, and have sworn allegiance to Islam and the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. During the war with Iraq in the 1980s, tens of thousands of them marched to certain death. Originally formed to face external enemies, the forces have become a semi-professional internal security force for the Supreme Leader. Young and unchecked, they have been blamed for some of the worst abuses against demonstrators including brutal rapes.

<17> Many of the people I know who have spent time in Iran have never met a Basiji off the job. Over the years some have gotten away with murder and abuse, all in the name of Islam. They have betrayed their cohorts, spied on strangers, and acted as security during times of unrest. They are despicable.

Sleeping Monsters

<18> Becoming a Basiji – a member of Iran’s paramilitary – is a decision many make when they are 11 or 12. It’s something you do when you are the type of kid who dreams of changing the world, I was told. You’re an idealist, dreaming of a better future. You want to be involved. You want to be active and engaged. When you are a Basiji, you go to camp, travel, are practically guaranteed a place in Iran’s competitive universities, and can avoid military service.

<19> The Basiji are the State’s activists; the counterpart to Iran’s human rights defenders, journalists, women’s rights advocates, and Reformers. Kamran calls them Sleeping Monsters. Despite all this, my own experience with members of the Basiji did not always fit the neat narrative of the monster.

Agha A.

<20> In Iran, I ate a dinner of lentils and stewed lamb, while sitting on a red Persian carpet in the home of a woman with two sons in the Basij and one dead in in the late 80s during the war between Iran and Iraq. On the wall hung a painting of a Shia hero on a horse with a floating white hand dripping blood and pierced by an arrow: very Mexican Gothic. In a nearby room, women were gathering to mark the death of Mohammad’s grandson Hossein in an ambush in Karbala and the sad music that tells of that fatal day was emanating from a small boombox in the corner. A caged canary chirped on the porch.

<21> I called her son Agha (Mister) A. even though he was still in college. He was tall and skinny, awkward, quick to blush, and kind. Yes. Kind. I knew him because he was assigned to befriend us, a demi-spy. It was no secret. His brother showed off the canary in the corner and his young niece slept on the floor beside us. In 2005, when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the controversial president of Iran, was elected for the first time, this tall Basiji told me that the man was dangerous; he will destroy democracy. He told me of the rift within the Basij between those who supported the candidacy of the former president, Akbar Rafsanjani and those who supported the upstart Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. As he told it, this was a rift between democracy and oppression.

<22> Sometimes I hold Agha A in my head when I am trying to model the situation in Iran. I wonder if he would accept the abuse of prisoners? Would he participate? Dissent? Avoid? Would he ride on the back of a motorbike hitting others with batons? It is my way of preserving some of the complexity, of refusing to simplify the story of what is happening in Iran. It is my way of holding out the possibility of communication.

Adrenaline Junkies

<23> In a village north of Tehran, a young man avoided calls to join his fellow Basiji in securing demonstrations. “I am a Mousavi supporter,” he told a mutual friend. “At the beginning everyone talked about who is supporting whom. It wasn’t a big deal. Now it is more difficult. It is like you have entered a beehive. The commanders know who supports whom, but it doesn't matter when it comes to security assignments. I have friends who go to actions because they like it. Some of them even support Mousavi and the opposition.” His friends are adrenaline junkies. They have nowhere else to release their energy. Demonstrations are rock concerts. Politicians are stars.

<24> “If it becomes too cruel, I don't think anyone will go,” the woman relating the Basiji’s story said. “That’s my sense. This guy was scared. If it goes too far, he might be in trouble because everyone knows he is a supporter of Mousavi. If it goes too far, people will have to take sides.”

<25> “Has it gone too far?” I asked.

<26> “I don’t know. I hope not,” she answered.

I Am Thoroughly Ashamed

<27> For at least one member of the Basij, it has gone too far. He fled Iran to ask for asylum in the UK. In an interview with Channel 4, he told the story of how he was arrested and tortured for registering his dismay at the way prisoners were being treated. “I am thoroughly ashamed. I'm ashamed before God, ashamed of my youth, ashamed in front of my friend, ashamed in front of the people. I only thank God that during these arrests I never harassed anyone.” [6]

There's the poem that says ‘Human beings are members of a whole’. My friend, the people, myself, you, others, we are all one. Any one person's pain can affect everyone, can disrupt calm.

I have this terrible feeling of pain, that I spent the best years of my life unaware. They used this. I was a tool for them to reach their objectives. I unwittingly got involved in their plans. I was unknowingly led by them.

Their slogan was that we were the force of the people, the eminent ones, that we must lead. We were unaware of what they brought on us. Our thoughts were not our own.

I think of this young man, and my heart breaks. I think of the young Basiji who, unlike him, are acting as security at demonstrations, who are raping and torturing the people they arrest, and who will wake up one day as damaged and regretful adults like this taxi driver Kamran and I met in Tehran in 2005:

“I was a member of the Basij…But it soon became clear to me that it was just a group of people out for revenge. They told me, go and get your revenge, but I told them: why should I do that? I joined because I believed in Islam and the revolution. All those guys believed in was vengeance.” …

“What religion tells you that it’s okay to lie, cheat, and steal? Here in Iran, you cannot function without lying, cheating, or stealing.”

“This is not Islam,” the driver says. “This is its opposite.” [7]

<28> Attempting to understand those who harbor doubts is so much easier than trying to understand those without. I do not have the courage to face the brutality that comes with certainty. I don’t have the stomach to even try to get into the head of those who abuse with impunity, kill in the name of ideology, or relish a good old fashioned hanging. They are activists too. I guess. They are activists who tell a radically different story to themselves than I do.

Those Little Grey Areas

<29> Just a few months ago, I believed that activism was for idealists, dogmatists, youthful and young people with a simplistic view of the world. I could never imagine myself as an activist because I had confused activism with dogmatism. I had constructed a definition of an activist as someone who did not actually consider consequences. For me, the whole world was and remains filled with grey areas. The challenge for me has been to learn to act for a cause without losing a sense of the complexity involved.

Glorious Complexity

<30> Why Iran? That’s a harder question and one related to my own seriously insane love affair with the country. Recently, a friend we made in Iran was visiting us in Amsterdam. When she left I wrote a sappy email, “When I took Nazlia to the airport I felt such a wave of sadness as though Iran were a kind of vessel for my soul and that it had broken. I know that's overly poetic, but it is the most accurate description I can give. I have been to a lot of places in my life, but only Iran ever felt like it should belong to me.”

<31> Even though I am actively working for a free Iran, I cannot manage to tell myself a story with a happy ending. At best it ends with more social freedoms, but without essential freedoms. At worst it ends with a terrifying crackdown that shuts society down for years to come. Still, one day I hope to kiss the ground of a free Iran with all of its glorious complexity intact.

Notes

1 Gareth Smyth. 2006. Fundamentalists, Pragmatists, and the Rights of the Nation: Iranian Politics and Nuclear Confrontation. A Century Foundation Report. p. 35

2 The Neda referred to here is Neda Agha-Soltan, whose death in Tehran by gunshot during a June protest was captured on video. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_of_Neda_Agha-Soltan (Accessed February 21, 2010)

3 Excerpt from Khamenei’s first Friday sermon after the elections: “When extremism starts in a society, any extremist move can fuel other's extremism. If the political elite ignore the law, or cut off their noses to spite the face, whether they want or not, they will be responsible for the bloodshed, violence, and chaos (that will follow).” English translation on the blog Informed Comment. http://www.juancole.com/2009/06/supreme-leader-khameneis-friday-address.html (Accessed February 21, 2010)

4 http://hnn.us/articles/112050.html History News Network. Hamid Tehrani. Anti-Semitism Vs Anti-Semitism in Iran. (Accessed February 21, 2010)

5 http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2009/10/05/is_mahmoud_ahmadinejad_jewish (Accessed February 21, 2010)

6 February 17, 2010. Channel 4 News. Basij militia member's story: full transcript http://bit.ly/akQ11a (Accessed February 18, 2010)

7 From the blog by the author and her husband, Kamran Ashtary, View from Iran http://viewfromiran.blogspot.com/2005/11/taxi-talk.html (Accessed February 21, 2010)

Return to Top»