Reconstruction 10.3 (2010)

Return to Contents»

Reminiscences: Locating the Traumatic Object/ Emily Leger

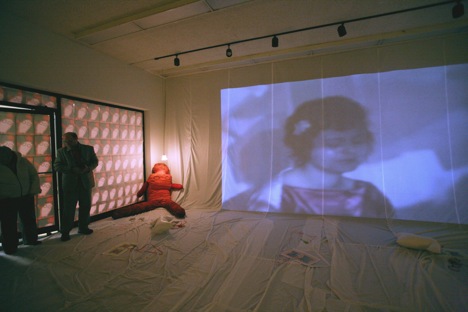

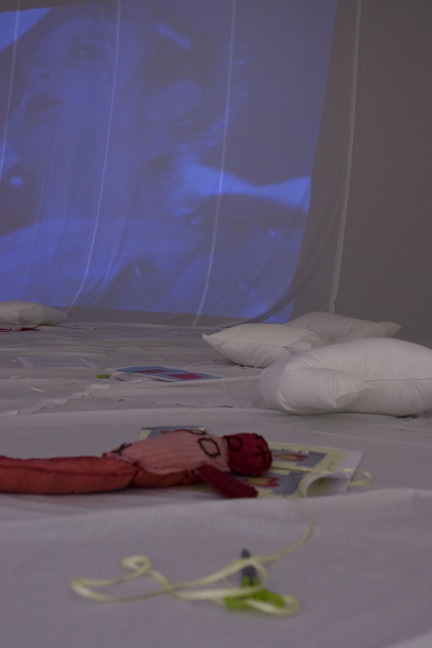

Installation Detail, Reminiscences, 2009.

Installation Detail, Reminiscences, 2009.

Abstract

Reminiscences is an installation of digital images, video, and soft sculpture that presents experiential trauma in a ‘multiple’ autobiography. The viewer is asked to consider how theory, particularly art history and art criticism, may be omitting the complicated messy details and multiple vantage points of trauma survivors. Primarily, the exhibit explores relationships between myself, a survivor of sexual abuse, rape, and paternal incest; a character I created, Emmy Brown, who is a response to my experiences; and the viewer. The installation intends to produce a situation for play that is both overt and antagonistic and that coaxes the viewer into the role of translator. My desire to locate the traumatic object surfaced from an analysis of the origins of Emmy Brown. Is she my child, my little sister, or a representation of one of my child states? Considering psychoanalyst Juliet Mitchell’s ongoing positioning of the object, Reminiscences searches to include the tangled details of the family. Do theoretical interpretations of trauma rely too heavily on a Lacanian subject? Inspired by clinical literature on trauma, Reminiscences questions the politics of disclosure and considers those who have no access to recovery. Reminiscences invites the translator to verify or falsify testimony. As Emmy Brown discloses, the translator is asked to intervene, is invited to tell or keep secrets, and is permitted to walk away.

Reminiscences: Locating the Traumatic Object

<1> Lacan defines three separate orders in the development of the ego: the Real, the Imaginary, and the Symbolic. In "From Simone de Beauvoir to Jaques Lacan," Toril Moi describes the impact of Lacan's seminal 1936 essay, "The Mirror Stage," on feminism. The Real, Moi states, is defined as fragmented, and the child enters the mirror stage through a shift into the Imaginary order to endow the baby with a unitary body image. Furthermore, Moi argues, in the Imaginary there is no difference and no absence, only identity and presence; however, to remain in the Imaginary is equivalent to becoming psychotic and incapable of living in human society. So, the child must move into the third order-the Symbolic-where the Law of the Father separates the child's identification with the mother's body; consequently, the child comes to define itself as separate from the other [1].

<2> In her essay from the 2003 symposium “Theory as an Object,” reprinted in the summer 2005 issue of October, Juliet Mitchell asks us to consider how art criticism might use psychoanalytic theory. Mitchell outlines a shift towards “positive destructiveness”; this shift makes necessary a clarification of the complex historical position of the object. Mitchell distills this necessary clarification from David Winnicott’s 1968 paper “The Use of an Object and Relating through Identification.” Mitchell reminds us that from within her current perspective of “object relations psychoanalysis” the “object” is a person; a feminine person. This person, Mitchell asserts, who occupies the position of object, not subject, is endorsed in Lacan’s readings of Freud. Importantly, Mitchell is well aware that relocating the object is an extremely difficult task. Mitchell confesses her limited clinical and textual approach and she acknowledges criticism of her 1974 book Psychoanalysis and Feminism. Mitchell identifies a mistake in her earlier writings; she notes her ahistorical moment when she mistakenly removed women from the family context. With added clarity, Mitchell complicates the revolt against the maternal body that originated from a criticism of Lacan’s model of gender differentiation; she suggests how this feminist revolt against the otherness of the object was simplistic [2].

<3> I am referring to the historic politics of removing women from the family context that was used to argue for a position of sexual sameness or equality; this approach was simplistic and essentialist. Mitchell quotes Quintin Hoare a critic of her 1966 paper “Women: The Longest Revolution,” who, in 1967, argued against Mitchell’s abstract and ahistorical position. Hoare states that the whole historical development of women has been within the family and she argues that women cannot be separated from the family.

<4> Considering Mitchell’s ongoing positioning of the object, Reminiscences problematizes domesticity and the family context. The installation incorporates domestic activities such a embroidery and sewing; the video projection repeats songs and stories shared across generations and contributes family testimony. Reminiscences searches for an inclusive discourse of trauma; a discourse of survivorship that includes the family to unearth the elemental and the experiential sites of trauma. Does survivorship rely too heavily on a Lacanian subject? Does a theory of trauma that includes the family make necessary a distancing from the subject? Cautiousness about the subject position triggers a psychoanalytic paradox: to activate and reclaim the object we must be willing to destroy it and move away from the object towards the Symbolic. Reminiscences approaches the other, and under an unknown shadow risks psychotic encounters with the Imaginary. White fabric covers the entire floor of the gallery and extends up one wall to create a screen. Each viewer chooses if and chooses how enter the gallery. Upon entering the space the viewer trespasses onto the screen and engages with the traumatic Real [3].

<5> I am speaking here of my own extension of the term traumatic Real to include trauma survivors. This extension arose from my response to Hal Foster’s 1996 book The Return of the Real. Foster uses the Lacanian psychoanalytic model of the gaze and locates a traumatic encounter with the Real that is antagonistic and bold. Within Foster’s traumatic subject is a strange rebirth of the author as witness, testifier, and survivor, found in the paradoxically absentee authority of the traumatic subject. Foster’s traumatic subject is very active and integral to my own position.

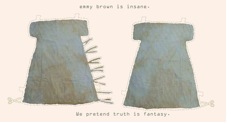

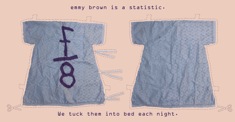

<6> Reminiscences features the character of Emmy Brown; Emmy Brown messes around with subject-ness. The character of Emmy Brown is in many ways a coping-mechanism. She told secrets, and exposed traumatic memories; she keeps telling. Emmy has appeared at least twice: once as a protective child state to repress and deny paternal incest and sexual abuse, and again as a young woman struggling with new sexual traumas, resurfacing memories, multiple dissociative and destructive child states, real psychosis and mental illnesses. Reminiscences catalogues eight digital prints of Emmy’s cut-out-doll dresses transformed into paper doll book “Pages”; these miniaturised digital dress images are flattened into the format of a paper doll book:

<7> These hand-sewn dresses are Emmy’s uniform; the original pattern was inspired by the cut out paper doll. Emmy’s original performances engaged the public with her very private disclosure:

Digital prints, (13” by 24”), mounted in white fabric; from “Pages,” series of 8 including “Page, Emmy Brown Insane;” “Page, Emmy Brown Split;”“Page, Emmy Brown Disagreed:”“Page, Emmy Brown Stat;”“Page, Emmy Brown Staged;”“Page, Emmy Brown Sat,”“Page, Emmy Brown Fakes;” “Page, Emmy Brown Falls,” 2009.

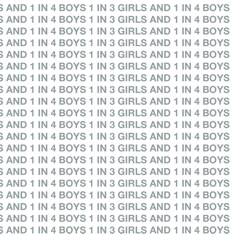

<8> These catalogue “Pages” are also reproduced as “Paper Doll Booklets” with an additional layer of text printed on the back of each paper reproduction.

Plain paper digital copies 2-sided with repeating text, (17” by 11”), ribbon and scissors.

<9> Each booklet corresponds to one of eight prints on the wall and is attached to a pair of scissors with a single long ribbon. Sound penetrates the gallery and the viewer is told the story of Emmy Brown; her telling. The voices of the video are those of a mother and of a maternal grandmother; these narrators are commemorated for their contribution to the project in a small plaque outside the gallery entrance:

Engraved plastic, (10” by 6”), installed outside the Gallery entrance.

<10> These intergenerational narrators contribute testimony; they also contribute heirloom fabric hand dyed and hand crafted into three “Large Therapy Dolls”:

Various dimensions (greater than 72” lengths), hand dyed heirloom fabric and fiberfill, hand sewn, embroidered and stuffed.

<11> Similarly, “Small Therapy Dolls” are also hand sewn using the same fabric. These smaller dolls accumulate over the duration of the two week exhibit:

Various dimensions (less than 30” lengths), accumulating quantity, hand dyed heirloom fabric and fiberfill, hand sewn, embroidered and stuffed.

<12> The viewer is given multiple opportunities to view Emmy’s dresses. Each digital print and each large doll is installed under a single hand crafted, dress-like, hanging lamp. The dimly lit gallery is transformed with over 1000 square feet of white fabric and the viewer is invited to sit amongst scatterings of cut-out “Dress Pillows”:

Installation detail, fabric, fiberfill, various dimensions, and accumulating quantity.

<13> By activating the horizontal space of the child lower to the gallery floor the viewer is encouraged to linger, and to participate; the viewer can witness and reminisce. One wall of the gallery is entirely covered in white fabric onto which, “Reminiscences,” an 18 minute video loop, is projected:

18 minute video, 2009 Installation of Projection Video, Greater than 1000 square feet of hand stitched white cloth,loop with 4 speakers and surround sound, and 11 hand crafted lamps suspended for ambient lighting.

<14> There is no way to enter the gallery without interacting with and stepping on the exhibition.

<15> Through the testimony of Emmy Brown and inspired by clinical literature on trauma, Reminiscences questions current politics of disclosure. Reminiscences searches to include the multiple vantage points of trauma survivors. Furthermore, Reminiscences questions the present-day attraction to the traumatic subject; the viewer situates the larger historical contexts of trauma and art. Attraction to the subject is both normative and narcissistic; by destroying the object that is us, or who is related to us, we can forget by dissociating. Reminiscences presents experiential trauma in a multiple autobiography; the exhibit explores the perplexing relationships among Emily Leger, Emmy Brown, and the viewer. In other words the viewer is asked to question disclosure; and encouraged to consider if the voice in the exhibition is singular, authentic, or if it is truthful. Multiplicity helps the work move beyond autobiography to include other trauma survivors, particularly other sexual abuse and sexual assault survivors. Reminiscences intends both to locate and to include those who are missing. In many ways these missing subjects are far from the gallery and far from the art context; alone on an island the traumatic subject is rescued. Clearly this model is flawed. Why do we isolate trauma survivors by pigeonholing autobiography and testimony? What would a new model look like? Is domestic trauma relevant to art making? Is it easiest to forget? In pursuit of an inclusive discourse for the trauma survivor that reclaims power from the domestic, experiential site of trauma without claiming autonomous sanctity from criticism. Reminiscences, postulates a traumatic object that does not replace the traumatic subject; the exhibit attempts to foster a tension of “coexistence.” [4]

<16> An in-depth historical account of the relationship between the object and the other in the development of the subject is missing from this discussion. Mitchell does not advocate for a simple approach; she does not imply that there is an object, traumatic or otherwise that might replace the subject. My approach is to move psychoanalysis towards cultural theory. Mitchell alerts us of a tension between the original female subject and her analyst who occupies the position of other (the object); Mitchell warns us not to move between these positions but asks us to hold them in a tension of coexistence.

<17> In her introduction to the summer 2005 issue of October, Mignon Nixon clarifies one of Mitchell’s art-relevant distinctions: one must “use” rather than “relate” to theory; one must not be obedient to theory, rather, one must use it as an analytic object. Nixon predicts that such an object would be multifaceted; the analytic object would embody the person of the analyst, the technique, the setting, and the theory. This issue of October is seminal to Reminiscences for many reasons. In much the same way that clinical literature allows advocacy for missing trauma survivors, the interaction of psychoanalytic texts and art criticism allows advocacy for a missing context: the emerging traumatic object, her person as analyst, her setting, and her technique. Advocating for art that is made about real psychic trauma requires not just that there are listeners and witnesses, but also co-authors and co-confessors. Understanding the context for such an art means understanding and combining the positions of others. Nixon notes Mitchell’s encouraging advocacy for psychoanalysis that offers “the most profound analysis of patriarchy available to feminism.” Mitchell’s inclusiveness requires caution; separating the survival of psychoanalysis from the politics of trauma within the family is precarious [5].

<18> Speaking of Juliet Mitchell’s involvement with Mary Kelly’s “Postpartum Document,”Nixon locates the introduction of an absent maternal subject. This absent maternal subject and the fragility of her position is relevant to an emerging traumatic object. Reminiscences attempts to present the complicated position of a motherless traumatic subject as absent through the story of Emmy Brown.

<19> In Addition, another important “coexistence” is evident between Mitchell’s second generation feminist absent maternal subject and her contemporary analytic object. In Reminiscences the traumatic object is a person; she is also a position that coexists with the traumatic subject. Examining Emmy Brown’s origins led to interest in the “coexistent” position of the object. Is Emmy my child, my little sister, or a representation of one of my protective child states? The fact that Emmy Brown would or could not exist without me confirms our lack of separation. When I was six and again when I was twenty-six, Emmy Brown lashed out protectively against the family and against the other. Emmy Brown performed trauma and exaggerated for the viewer my experiences of telling. Emmy Brown continues to reenact the frustrations of not being heard. Emmy Brown disconnects herself from the family and revolts simultaneously against her abusers, her parents, and others in positions of power and authority.

<20> In her 2004 interview, reprinted the summer 2005 issue of October, Juliet Mitchell defends her horizontal field as a lateral shift away from an intergenerational model of psychoanalysis. The intergenerational model focuses on both the object, and the other, as parental relationships. Mitchell’s shift towards intragenerational lateral relationships locates a sibling and peer psychoanalytic model. Mitchell demands us to confront the limitations of a traditional intergenerational psychoanalytic model; specifically those limitations associated with gender differentiation and feminism. In doing so, Mitchell revisits Freud’s pre-psychoanalytic writing; within Freud’s hysteria she reestablishes psychic trauma. Interestingly, Mitchell notes that Freud’s hysterics suffered from childhood abuses; she clarifies that trauma has both elemental and experiential components. Additionally, Mitchell also acknowledges that lateral sibling peer relationships occur as an Imaginary relation as opposed to a Symbolic relation. Put another way this lateral model engages with fantasy more than language. Mitchell’s new age of psychoanalytic theory is founded on the tension of coexistence between intergeneration coordinates (subject and object) [6].

<21> Within her new model Mitchell extends traumatic elements to not only include traumatic experiences but also the trauma of a screen memory, a memory that is the narrative history of what mattered in your life. Mitchell exposes the limitations of the lateral, horizontal field and admits that sibling relationships are subsidiary and they lack staying power. Interestingly, Mitchell introduces real trauma into her discussion of siblings. Sibling incest, she notes, is the most prevalent of (reported) sexual abuse in the United Kingdom. I do not have time to mention Mitchell’s discussion of the Law of the Mother in Sibling relations.

<22> Within Emmy Brown’s performances there are interactions between psychosis and a failed attempt at neurosis; one might argue that Emmy Brown is both a traumatic subject and a traumatic object. Her disclosure is contradictory and problematic. In Emmy’s early performances she performed trauma within sculptural installations that were in close dialogue with a Lacanian model of the gaze. Through art making she explored Lacan’s model of gender differentiation. In addition, Emmy acted out a Kleinian model of aggression by re-experiencing traumatic memory, performing childhood trauma, and acting out the defiant and aggressive moods and actions of the child. Emmy created oversized objects of primary experience including enlarged L shaped keys to her bedroom (“Emergency Keys”, fabricated steel, 2000.), and enormous toddler style cutlery (“Tweety Bird Forks”, fabricated steel, 2002.). Emmy negotiated the flat horizontal space of the infant, accentuated with patterned floors and hanging strips of cloth. Also, Emmy moved in and out of hidden spaces beyond the literal screen and interacted with video projection saturated with references to psychoanalysis and trauma theory. Emmy Brown was protective and she was resilient; she possessed the strength to tell secrets. Reminiscences revisits Emmy Brown and opens up more telling. Emmy Brown rejects her subjectivity by refusing to end her disclosure. At the same time, through her actions, she rejects the object by refusing the comfort of the maternal body; she moves dangerously close to psychosis and to the Imaginary. Emmy Brown’s repetitions and reparations are torn apart, interrupted and exposed to the audience. In part, Emmy reemerged as a reaction to Mignon Nixon’s 1995 article in October entitled “Bad Enough Mother.” In this article Nixon locates a return to psychoanalyst Melanie Klein within the work of 1990s feminist artists who through their art-practices returned to the drives and to aggression. Nixon allocates space and importance to artists who reenact traumatic experiences; she views this return to Klein not as a theoretical regression but rather as a repositioning. These artists offer a critique of feminist psychoanalytic work of the 1970s and 1980s that privileged pleasure and desire over hatred and aggression [7].

<23> Nixon stresses that a shift away from Lacan is a shift in emphasis from neurosis to psychosis. Reminiscences proposes that there is a lateral space, however temporary, for a traumatic object; a space that exists in dialogue both with Nixon’s return to a Kleinian horizontal field and with Mitchell’s intragenerational model. In Reminiscences, Emmy Brown simultaneously approaches, coexists with, and denies both the Imaginary, and the maternal body. Early on, Emmy Brown declared herself to have no parents. As a kind of Lacanian orphan, Emmy cuts into the Imaginary to locate a traumatic object [8].

<24> Nixon argues that within the Bad Girls exhibition, subjectivity forms from an experience of loss enacted through destructive fantasies. Nixon highlights artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Rona Pondick, Janine Antoni, and Rachel Whiteread; she argues that the desire of the little girl to speak is fulfilled in a desire to bite, to cut and to devour the one who oppresses her with his speech. Emmy Brown performs this talkback literally by introducing Klein’s “tdaddy” into her performance video in “C’est ne pas Un pere”(sic)*.

<25> *As first noted in “Performing Childhood Trauma,” the title “C’est ne pas un pere” is grammatically incorrect; a combination of "This is not a father," and "it was not my father." This is a pun referencing Rene Margritte's surrealist painting "Ceci n'est pas une pipe."(This is not a pipe.).

<26> Nixon seems to have updated her position by readdressing aggression and fantasy. Drawn towards Juliet Mitchell's lateral, horizontal space, Nixon redefines the manner in which psychoanalysis intersects with art. Within the context of the Twenty-First Century, Nixon repositions the role of the artist. Within this repositioning, Nixon identifies Mitchell’s “good enough theory” that survives beyond a docile interpretation of texts. Without this theory the artist, the analyst and the other move towards the banal, the modest or the sentimental. Interpreting art, Nixon warns, carries with it the same dangers as interpreting text or theory. Reminiscences attempts to consider both the textual and the theoretical interpretation of art. Emmy actively rejects the banal; her performances create a treacherous space for the audience who witness psychosis, pain, destruction, and aggression. Where is the world that created Emmy Brown, the world of no parents, of self-parenting. Where is the world that interacts with fantasy and cuts into the Imaginary from within a maternal body without claiming an objective or ahistorical position? Importantly, Nixon reminds us the current context of art interpretation can become inactive [9].

<27> Another important installation detail of Reminiscences is the “obstructed windows.” By covering the windows with photo-replicas of the “Small Therapy Dolls” Reminiscences entices and coaxes the viewer into the gallery. At the same time the exhibit delivers painful disclosure in a shocking reveal. The viewer is invested in spectatorship just by opening the door.

Installation Detail, Reminiscences, 2009.

Plain paper digital copies, greater than 200 copies of small therapy dolls, folded and taped.

<28> Ideally, within this individual exchange, Reminiscences extends an opportunity for the viewer to co-confess. Emmy Brown makes it clear that she is a survivor of sexual abuse, rape, and of paternal incest. Reminiscences relies on others; autobiography is only one component of the installation. In pursuit of art that is active Reminiscences is informed by artists who have extended their work to include the family and the community. Many artists have attempted to use the private in their art-practices; many others continue to identify with the public and to enact social activism through art. Haunted by the short reflection on Felix Gonzolez-Torres, “Community of Loss,” found in Claire Bishop’s 2005 book, Installation Art: ACritical History, I continue to struggle with art making stereotypes including pity art, art from the margins, “art brut,” or even identity art [10].

<29> I am especially interested in Nixon’s repositioning of the artist and have reframed and extended ideas from Mignon Nixon, “Introduction” to Juliet Mitchell. This repositioning of the interpreter is particularly relevant to my own positioning of the viewer as a translator.

<30> There are interesting overlaps between contemporary psychoanalytic texts and Claire Bishop’s writings on performance art, namely, the interpreter. In her 2006 book, Participation, Bishop presents her analysis of the Brechtian Model in which the audience is involved in constructed situations; her analysis becomes particularly interesting when she posits a situation where in the spectator becomes an interpreter [11].

Installation Detail, “Pages”, 2009.

<31> I will mention some other sections of interest in “Activated Spectatorship” that highlight topics such as “Relational Aesthetics,” “Relational Antagonism,” and “Making Art Politically.” Although there is much to be gained from considering these writings I will not take on this endeavor here.

<32> In his 2004 essay, “Chat Rooms,” Hal Foster cautions artists who engage in community based art practices and expresses reservation about an excessively optimistic rhetoric that accompanies collaboration and participation in art [12]. Reminiscences produces a situation for play that is both overt and antagonistic, and creates a situation that coaxes the viewer into the role of a translator. In other ways, Reminiscences allows the viewer to witness and console; the viewer interprets the languages of psychiatry, psychoanalysis, trauma, autobiography and art. In Reminiscences the viewer is given opportunities to witness and to participate. The viewer is invited to sit and cut out Emmy Brown dresses. Reminiscences shares with the viewer the intimate details of survivorship; the viewer is invited to be and share Emmy Brown. How willing is the viewer to interpret? How much personal experience does the viewer have with the different languages of trauma?

<33> This paper barely grazes the surface of contemporary trauma theory, its variety, its scope, or its profundity. Laura Frost’s “After Lot’s Daughters: Kathy Harrison and the Making of Memory” helps contextualize autobiography about domestic abuse, particularly, autobiography about incest. Despite the abundant theorization of trauma, and despite the courage of many, sharing traumatic experience from within the family remains extremely difficult. Emmy Brown performs her trauma and shares her experiences. Emmy Brown speaks both rationally and from within a psychotic state. She shares intimate details of her family, her lack of family, and her destruction of her family. Reminiscences invites the translator to verify or falsify testimony; the translator is asked to intervene, invited to tell or keep secrets, and is permitted to walk away and shut the door. Frost laments that although incest stories do have their own literary genre it is a genre that belongs to the literature of the extremes [13].

<34> In the Introduction to their collection of essays, Extremities: Trauma, Testimony, and Community, Nancy Miller and Jason Tougaw note the fact that in the new millennium we live in the wake of trauma; trauma is the symptom of our new age. Miller and Tougaw extend Cathy Caruth’s 1996 collection of essay’s Trauma: Exploration in Memory to reflect upon the current extreme situation in which sharing traumatic experience becomes a commodity. Unfortunately, Extremities seems to further marginalise those who speak out against oppression. It would seem that the more plentiful the voices of taboo subjects become the more sceptical academia becomes of the relevance of testimony.

<35> Revisiting trauma is a necessary part of healing. Reminiscences realistically focuses on ongoing challenges with wellness and mental health as Emmy Brown walks the boundaries of wellness and engages with psychiatry [14].

<36> How is childhood trauma survived? What constitutes resilience? The term resilience emerged in 1987 from the set of generative writings within The Guildford Psychiatric Series entitled The Invulnerable Child. In his Introduction to this volume editor E. James Anthony defines resilience as a relationship between risk and vulnerability. Anthony defines four types of invulnerability; the one I am the most interested in is developed by an individual who learns how to “bounce back” from traumatic exposures. Anthony points out how this theory was developed to overcome the victimization hypothesis; significantly, he concedes that resilience can be strengthened by external social support systems [15].

<37> Anthony positions himself within L. E. Hinkle’s definition of resilience as the presence of certain personality traits, characteristics that insulate the individual from detrimental life experiences. Excessively resilient individuals demonstrate an ostrich effect and are invulnerable; these invulnerable risk developing sociopathic traits. Interestingly, within the field of psychiatry there exists a literal ‘Good Enough Mother or Caretaker” who is instrumental in protecting a child. In Reminiscences I interject my mother’s perspective about Emmy Brown and her telling.

Installation Detail “Reminiscences”, 2009.

<38> The character of Emmy Brown represents personal resiliency.

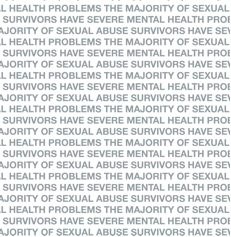

<39> Clearly, the luxury of reminiscing means that a certain urgency has faded as time has passed. Nevertheless, resiliency does not lessen or destabilize sexual abuse or the politics that surround disclosure. The silences from within the site of domestic trauma are both tragic and pervasive. In their 1998 article published in the American journal Child Abuse and Neglect entitled “Prevalence of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Other Psychiatric Diagnoses in Three Groups of Abused Children [Sexual, Physical, and Both]” Ackerman et al. give some context to domestic abuses and the consequences of these abuses on children. Significantly, they point out trauma’s “extreme” definition as being focused around victims of war, natural disaster, kidnappings, or shootings; in their article they not only include but focus on childhood sexual and physical abuse. According to Ackerman et al. many, but not most, children who are affected by trauma are highly resilient and do not develop stress disorders. However, they emphasize that the most important impact of their research into resilience is to expose the prevalence of abuse and to reveal the magnitude of the emotional damage this abuse inflicts on most children. Although their study samples a relatively large number of abused children, they readily admit that their sample is limited and only consists of children whose abuses were discovered or disclosed to a supportive adult [16].

<40> In their study Ackerman et al. found that more boys were physically abused and more girls were sexually abused. They also stress that many children and caregivers who were approached declined to be interviewed.

<41> Similarly, in their 1987 article from the same journal, entitled “Resilience in Child Maltreatment Victims: A Conceptual Overview”, Mrazek and Mrazek report that the situation of childhood trauma is grave. They argue that despite resilient functioning, and unlike other childhood illness, those illnesses associated with maltreated children do not often come with a prognosis of full recovery. We must consider that child victims of abuse are underrepresented in scientific literature. We must also consider that adult survivors are also missing. These traumatic subjects are further marginalized by psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, and severe mental illnesses. Mrazek and Mrazek broaden our perspectives and disclose that reported incidents of child abuse and neglect continue to be dramatic throughout the world. According to their research, the most important characteristics of resilience are optimism and hope. They advocate for protective factors both from within the family and extending out towards the larger social context. Scientific research shows that the ability to survive trauma depends on individual resilience. Resilience, having both natural and nurturant components, can be cultivated and promoted. Although much is known about the very small number of children who have resilient functioning, almost nothing is known about the majority. Little is known about those trauma survivors who develop emotional or psychiatric disorders as a direct result of childhood sexual and physical abuses.

<42> I am always conscious of the ivory tower position I hold. I owe my family a great deal(including my father). Making art that speaks and acts out against child abuse and neglect will never be enough to make up for my privilege. I have a great education and the ability to look both rationally and creatively at trauma. I have relied on the Government of Canada for inpatient and outpatient psychiatric care, psychotherapy, medication, and Income Assistance (welfare) during periods of illness [17].

<43> Mrazek and Mrazek list seven protective factors including (1) being a middle or upper social class; (2) having educated parents; (3) having no family background of psychopathology (mental illness); (4) having a supportive family milieu (social environment); (5) having access to good health, educational, and social welfare services; (6) having additional caretakers besides the mother and; (7) having relatives, especially grandparents, and neighbors available for support. I have added italics to the 5 out of 7 protective factors that influenced my resilience and that correspond to my position of privilege. It is important to again consider, as Mrazek and Mrazek do, those many maltreated children who do not have access to protective factors and who suffer permanent psychological scars.

<44> Six and a half years after my expected graduation from The University of Florida, Master of Fine Arts Program, my pride in realizing Reminiscences is tempered by the realization that few this opportunity to express trauma. Success is overshadowed by dark bodies of guilt; sedimentary memory is stirred by hours of reminiscing. I realize that I am courageous but I cannot help but think of In Reminiscences, I reframe and distance myself from the traumatic subject. I make a lateral shift away from the subject towards a traumatic object by using both the theoretic and literal intergenerational model. I look for relationships of survivorship from within the family: my family and Emmy’s family. My own struggles with severe mental illness, including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Schizo-Affective Disorder, are typical among domestic abuse survivors. I have had the unique experience of two major diagnosed childhood conditions: severe mental health problems resulting from trauma and documented giftedness. How have these two concurrent experiences intertwined themselves? Clearly, I am fortunate. I hope Reminiscences can commemorate my support network who have nurtured my resilience. I extend a special thanks to Emmy Brown. Emmy is more than me, and she is a traumatic object, an analyst, a person, a little big sister, and my parental protector. Looking beyond the opportunity to give testimony, Emmy Brown embodied resiliency. Every other day, or more often than that, the topics of incest and sexual abuse surface in popular culture. There is no doubt in my mind that the witnesses of my trauma have truly saved my life. The real concern I have is that from this position of relative power and obvious privilege, I very nearly did not make it, many times over. On a personal level Reminiscences is proof of my strength and resiliency; simultaneously, Reminiscences is a sobering document of my fragmentation and my fragility.

Notes

1 Moi, Toril. Sexual/Textual Politics: Feminist Literary Theory (Second Edition). London; New York: Routledge, 2002, 99,100, summarised in Emily Leger, “Performing Childhood Trauma,” Wreck: Graduate Journal of Art History, Visual Art & Theory 1, (2004): 29-41.

2 Juliet Mitchell, “Theory as an Object*,” October 113 (2005): 28-30.

3 For a discussion of the limits of Foster’s traumatic subject see Leger, “Performing Childhood Trauma,” 29, 30.

4 Juliet Mitchell, “Theory as an Object*,” 30.

5 For more clarification on second generation feminism and art criticism see Mignon Nixon, “Introduction,” October 113 (2005): 3-8.

6 See more in Tamar Garb and Mignon Nixon, “A Conversation with Juliet Mitchell,” 14-19.

7 Mignon Nixon, “Bad Enough Mother,” October 71 (1995): 72-74.

8 Mignon Nixon, “Bad Enough Mother,” 71-92.

9 Mignon Nixon “Introduction,”3-6. Juliet Mitchell, “Theory as an Object*,”33-36.

10 For a more in depth look at Bishops perspective see Claire Bishop, “Activated Spectatorship” In Installation art: A Critical History (New York: Routledge, 2005), 102-27.

11 Claire Bishop, “Introduction/Viewers as Producers” in Participation. Ed. By Roland Barthes and Claire Bishop (London; Cambridge, Mass.; Whitechapel; MIT Press, 2006) 10-17.

12 Hal Foster, “Chat Rooms.” In Participation. Ed. By Roland Barthes and Claire Bishop (London; Cambridge, Mass.; Whitechapel; MIT Press, 2006) 190-5.

13 Nancy Miller and Jason Tougaw, Introduction to Extremities: Trauma, Testimony, and Community, edited by Nancy Miller and Jason Tougaw (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 1-21p

14 See my discussion of two of Emmy’s performances “No Supper” and “C’est Ne Pas Un Pere” in Emily Leger, “Performing Childhood Trauma.”34-37.

15 E. James Anthony “Risk, Vulnerability, and Resilience: An Overview”; in The Invulnerable Child. Ed. By E. James Anthony and Bertram J. Cohler (New York: Guilford Press, 1987), 3-48.

16 See especially the conclusion of Peggy T. Ackerman et al., “Prevalence of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Other Psychiatric Diagnoses in Three Groups of Abused Children [Sexual, Physical, and Both].” Child Abuse & Neglect 22 (1998): 769-74.

17 Patricia J. Mrazek, and David A. Mrazek, “Resilience in Child Maltreatment Victims: A Conceptual Exploration,” Child Abuse & Neglect 11 (1987): 357-66.

Bibliography

Ackerman, Peggy, T., Joseph E. O. Newton, W. Brian McPherson, Jerry G. Jones, and Roscoe A. Dykman. “Prevalence of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Other Psychiatric Diagnoses in Three Groups of Abused Children (Sexual, Physical, and Both).” Child Abuse & Neglect 22 (1998): 759-774.

Anthony, E. James and Bertram J. Cohler, Ed. The Invulnerable Child. New York: Guilford Press, 1987.

Barthes, Roland and Claire Bishop, Ed. Participation. London; Cambridge, Mass.; Whitechapel; MIT Press, 2006.

Bishop, Claire. Installation Art: A Critical History. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Garb, Tamar and Mignon Nixon. “A Conversation with Juliet Mitchell.” October 113 (2005): 9-26.

Leger, Emily. “Performing Childhood Trauma.” Wreck: Graduate Journal of Art History, Visual Art & Theory 1 (2004): 29-41.

Moi, Toril. Sexual/Textual Politics: Feminist Literary Theory (second edition). London; New York: Routledge, 2002.

Miller, Nancy K. and Jason D. Tougaw. Extremities: Trauma, Testimony, and Community. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Mitchell, Juliet. “Theory as an Object*.” October 113 (2005): 29-38.

Mrazek, Patricia J. and David. A. Mrazek. “Resilience in Child Maltreatment Victims: A Conceptual Exploration.” Child Abuse & Neglect 11 (1987): 357-366.

Nixon, Mignon. “Introduction.” October 113 (1987): 3-8.

Return to Top»