Reconstruction 10.3 (2010)

Return to Contents»

Ethical Spectacle: Memorial in a Time of War / Jeff Nall, Florida Atlantic University

Abstract:

In this work I will present the Ethical Spectacle: Memorial in a Time of War, a model for increasing support for peace and the anti-war movement. This model achieves this goal by undermining support for war by presenting what Stephen Duncombe calls an “ethical spectacle” which confronts a population with both the reality and dire consequences of their nation’s military actions and the moral dilemma such circumstances present them with. Specifically, the Memorial in a Time of War successfully bridges the gap between the anti-war worldview and that of lesser informed Americans. The Memorial in a Time of War accomplishes this by conversing with its audience via iconic language/visual culture and utilizing fundamental levers of mind change, articulated by Howard Gardner, including redescriptions of patriotic iconography and the resonance provoked by dramatically publicizing the deadly consequences of war. Both redescriptions and resonance overcome fundamental resistances such as the association of patriotic fervor with pro-war sentiments, as well as the resistances created by the sheer physical distance between American citizens and the war, and the media’s failure to close this gap. Another important characteristic of the Memorial in a Time of War is that it is capable of overcoming what many believe is a corporate blockade of anti-war voices in the mainstream media. To fully explicate the theory this work will consider Duncombe’s notion of the “propaganda of the truth” or the “manufacture of dissent,” the AIDS Quilt as an archetype for the Memorial in a Time of War, and analyze the American Friends Service Committee’s exhibit, Eyes Wide Open: An Exhibition on the Human Cost of the War, as the embodiment of the Memorial in a Time of War.

Keywords: .

<1> With anger over the Iraq war reaching new peaks, its popularity at new, historic lows, and an increasingly active campaign against the war in full-swing, there are many opportunities to speak out against it. Such events include street-corner rallies and mass protests. Such actions are a fundamental component to pressuring elected officials to do more to bring the conflict in Iraq to an end, as well as publicizing the growing discontentment of a large swath of the nation’s population. Opponents of the war, however, must also put a great deal of effort into expanding their base of sympathizers, supporters, and potential participants. To accomplish this, new, innovative methods must be designed in order to create an opportunity to engage people about the war, its consequences, and their responsibility as citizens. The question of course is how anti-war activists engage average Americans, many of whom do not support the war, but fail to relate to or understand the fervor of anti-war activists? While many register their disapproval of the war with opinion polls, much of the public remains unmoved to concretely act out against or at least ardently oppose the continuation of the war. How do anti-war activists create a bridge between their progressive world-view, which sees its own nation as an imperial giant wielding a maniacal foreign policy, and the average Americans’ apathy and/or emotional lethargy regarding the human cost of the war; and how can activists overcome restraints [1] such as Americans internalization of patriotic sympathies which have become the trademark of conservative, pro-war perspectives? More directly, how do anti-war activists succeed in more than merely conveying numbers (of dead) but also the visceral understanding of what such numbers mean, all the while respecting seminal American symbols (the flag, “the troops”) which are required to even begin a conversation with a large swath of the population? These questions reveal at least two key resistances which anti-war progressives must attempt to overcome. The apathy of the average American about the true human cost of the war directly influenced by the transformation of the public sphere as articulated by Habermas, specifically the corporate media’s refusal to publicize rational-critical debate. Research of mainstream media coverage of the lead-up to the Iraq war has shown an incredible bias for pro-war voices compared to that of anti-war voices. Similarly, today, despite the unpopularity for the Iraq war, the media gives almost no voice to grassroots activists, everyday people, and/or anti-war voices. It certainly does not show the dead, or give significant attention to the ever-increasing civilian death toll, which is not only the result of suicide bombings, but also U.S. air-strikes and raids. One of the key obstacles for anti-war progressives is an obstacle facing most modern grassroots movements: how do we deal with the transformation of the public sphere?

<2> In this work I will present the Memorial in a Time of War, a model for increasing support for, and active participation in the anti-war movement. This model achieves this goal by undermining support for war by presenting what we might call a spectacle which confronts a population with both a) the reality and dire consequences of their nation’s military actions and b) the moral dilemma such circumstances present them with. Specifically, anti-war activists can utilize the Memorial in a Time of War to successfully bridge the gap between their worldview and that of lesser informed Americans. The Memorial in a Time of War accomplishes this by conversing with visual culture and utilizing fundamental levers of mind change, articulated by Howard Gardner, including redescriptions of patriotic iconography and the resonance provoked by dramatically publicizing the deadly consequences of the Iraq war in a visceral way, which exhibit goers can intimately experience. Both redescriptions and resonance overcome fundamental resistances such as the association of patriotic fervor with pro-war sentiments, as well as the resistances created by the sheer physical distance between American citizens and the war, and the media’s failure to close this gap. Another important characteristic of the Memorial in a Time of War is that it presents progressive anti-war activists with a method to overcome what many believe is a corporate blockade of anti-war voices in the mainstream media. To fully explicate the theory this work will consider Stephen Duncombe’s notion of the propaganda of the truth or the manufacture of dissent, the AIDS Quilt as an archetype for the Memorial in a Time of War, and analyze the American Friends Service Committee’s exhibit, Eyes Wide Open: An Exhibition on the Human Cost of the War, as the embodiment of the Memorial in a Time of War.

<3> The Memorial in a Time of War must be understood as a tool for social change in a fundamentally transformed public sphere. Rather than merely relying on reason and evidence, though it utilizes both, the Memorial in a Time of War recognizes the reality of fantasy, and the necessity of capturing the imagination. In an essay titled, “Politics in an Age of Fantasy,” Stephen Duncombe pleads with his fellow progressive activists to open their doors beyond the levers of reason and research [2]. He complains that progressive devotees to the Enlightenment have grown dogmatic and conservative in their reliance on facts alone, leaving the task of implementing an imagined vision of the world to the right [3]. Progressives, it is true, are quite good at exposing “the lies of institutionalized power,” protesting, as in the “ritual ‘March on Washington,’” and educating University students. The problem, however, is that this three-pronged approach, which progressives do quite well, relies on an old faith in the power, effectiveness, and traditional aim of reason [4]. Duncombe why progressives appreciate the Enlightenment’s principles, but warns that today’s superstitious “fantasy” is an over reliance on “truth and reality, and faith in rational thought and action… [5]” Those who continue to remain pious devotees of the old model of Enlightenment’s empiricism and rationalism will be “doomed to political insignificance.” Today’s reality is that facts are not more powerful than fantasies [6].

<4> Duncombe urges progressives to utilize what Gardner describes as the lever of redescriptions. “Between arrogant rejection and populist acceptance of commercial culture lies a third approach,” writes Duncombe, “appropriating, co-opting, and, most important, transforming the techniques of spectacular capitalism into tools for social change.” [7] Duncombe goes on to criticize purest approaches to peace making which ignore important issues of resonance, yet another of Gardner’s levers. Duncombe cites a lecture given by philosopher William James, in 1906, when he argued that the problem with pacifism was that it, writes Duncombe, “ignored all the legitimate emotional needs that war fulfills: romance, valor, honor, and sacrifice.” [8] Even if one wishes to encourage a pacifist utopia, one can not fail to tend to the passions which motivate people. James wrote: “Pacifists ought to enter more deeply into the aesthetical and ethical point of view of their opponents, then move the point, and your opponent will follow.” [9]

Archetype for the Memorial in a Time of War

<5> In many ways the AIDS Quilt is the archetype for the Memorial in a Time of War. Notably displayed on the Mall in Washington in 1987, 1988, and 1992, the AIDS Quilt was conceived for the purpose of demonstrating that AIDS was an American epidemic and that, in the words of founder Cleve Jones, “America has AIDS.” [10] More specifically, the Quilt was a political tool to increase the allocation of economic resources to wage war on the disease[11]. To this end, organizers of the AIDS Quilt utilized redescriptions and research, overcame resistances and created emotional resonance among an otherwise unsympathetic and unmotivated public.

<6> The AIDS Quilt was criticized by some for its potential to create political passivity instead of political consciousness. Indeed, this seems like a likely complaint one organizing the Memorial in a Time of War would hear from fellow anti-war activists. One person complained that the AIDS Quilt seemed “indulgent, sentimental, defeatist.” [12] Others complained that it failed to “speak to the American public.” Capozzola writes, however, that while the Quilt had a political objective, that objective was not to provide a political answer to the question. The purpose of the Quilt was to provide “a political tool, enabling a politics that reflected its vision of pluralism and its accommodation not merely of demographic difference, but of political diversity as well.” [13] Indeed, the success of the Quilt was precisely its ability to articulate “the AIDS crisis in a ‘nonthreatening’ manner” for a broad swath of Americans. Despite accusations of essentially “selling out,” the founding organization (The Names Project), succeeded in bringing the AIDS issue into homes around the nation. Rather than offending the mainstream American consciousness, organizers employed traditional American symbols to capture the attention of a broad and diverse audience [14]. From this example the Memorial in a Time of War gleans that if our aim is to reach the greatest number of people in order to enlarge our movement, we must engage the American consciousness, not merely rage against its lethargy.

<7> Perhaps the most significant achievement of the AIDS Quilt was its ability to make a death toll that was difficult to conceptualize, seem vivid and emotionally communicative. “Instead of offering its viewers a symbolically empty screen upon which they project their individual interpretations and recollections,” writes Capozzola, “the AIDS Quilt provides a proliferation of symbolic material that onlookers themselves must make sense of by participating in the memorial.” [15] In fact, Jones’ motivation to create the AIDS quilt came from an obsession with “the idea of evidence.” Capozzola quotes Jones as having said: “I wanted to create evidence [of AIDS deaths] and by extension create evidence of government failure.” [16] The Memorial in a Time of War, too, has as one of its chief aims to convey an otherwise cold statistic with the energy and emotion countless deaths deserve. Because the memorial occurs during the war (or during the AIDS epidemic), it channels this emotion into a demand that one consider the future, and act accordingly. The AIDS Quilt created evidence by intertwining the two elements of memory formation, both commemorative (ex. gravestone), and monumental (ex. monument), with all of its political functions. Capozzola writes that the monument is aimed primarily at the future, and seeks to interpret loss or passing and to put it to contemporary or future political uses so that, in the words of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, ‘these dead shall not have died in vain.’” [17] The memorial, in affect, is a kind of interpretation of the past in an effort to create a future narrative. By bringing the commemoration of the dead out of the hiding of the cemetery, the AIDS Quilt created public site of memory, where the dead gathered together to tell their individual stories and collective story. [18] Instead of creating an environment of partisanship and sloganeering, the Quilt asked the question, what should be done [19]? In creating this question, the memorial also brings the uninvolved person closer to a sense of responsibility to preserve life; it asks those who bare witness, what will you do to resolve this problem? A change of course, an act or a justification must be made if the consequences are agreeable to the viewer. What follows is an analysis of the American Friends Service Committee’s exhibit of the cost of the Iraq war, “Eyes Wide Open,” as the embodiment of the Memorial in a Time of War. We also assess its success in terms of assisting efforts to end the war in Iraq.

Embodiment of the Memorial in a Time of War: Eyes Wide Open

<8> On March 18, 2008 a production of the American Friends Service Committee’s exhibition of the human cost of the Iraq war, Eyes Wide Open, Florida, took place at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton campus [20]. Volunteers unloaded the 1,000-pound exhibit and proceeded to place 176 pairs of combat boots, each tagged with the names of Florida soldiers who had died in the war, in rows on the campus’ Free Speech Lawn. The exhibit, the embodiment of the Memorial in a Time of War, was also comprised of over 200 tennis-shoes representing the 80,000 to over 600,000 Iraqi civilians who had, at the time, died. In doing so, the Eyes Wide Open project provided compelling, vivid evidence of a bloody war that seems so distant and abstract to many Americans.

<9> In terms of specific content, the Boca Raton exhibit sought to unravel the abstract debate surrounding the war by and showing the naked consequences of the conflict: nearly 4,000 dead United States soldiers, at the time, and between 80,000 and 650,000 dead Iraqi civilians – noncombatant men, women, and children. The aim was to undermine the concept that the war in Iraq is a distant, abstract conflict, which does not really impact citizens in the United States; and that despite what one may feel about the rightness or wrongness of the war, one is not responsible for nor is hardly aware of the consequences of the war. The hope was that the exhibit would silently say: this is the real face of war and, as it is our nation’s conflict, you must accept responsibility for all that comes with it, including the deaths of people just like you. Furthermore, the hope was that it would confront each person with the moral question, can I in good faith continue to support this war; and if not, am I obligated to make an effort to bring it to an end?

<10> What made the exhibit particularly successful was its ability to utilize nearly all of fundamental factors or levers of mind change. One, the exhibit questioned the rationality of spending billions of dollars on a war which has resulted in not only thousands of American deaths, but as many as 650,000 Iraqi civilian deaths. Two, it presented the facts about the human cost of the war in a unique manner which successfully resonated with people coming from a variety of perspectives. The success of the “Eyes Wide Open” exhibit is that both conservative supporters and leftist opponents of the war could appreciate its content at different levels. Those singularly interested in the deaths of the American soldiers could be affected by the combat boots and the personal affects left with many of the boots. Those principally impacted by events with a local resonance could be affected by the more than a dozen combat boots representing soldiers who had died from South Florida counties (Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach). Those operating from a spiritual place might be affected by the way in which the tennis-shoes representing the civilian dead formed a large, bright-white cross amid the black combat boots. Finally, those frustrated with the overemphasis on the American death toll could appreciate the exhibit’s integration of representation of the civilian death toll.

<11> In other Eyes Wide Open exhibits the civilian shoes were often placed to the side. The Florida Atlantic University exhibit integrated the civilian shoes, in the shape of a cross, [21] into the grid. The format of the exhibit, featuring symbols commonly associated with conservative and pro-war elements, successfully utilized redescriptions. By incorporating nationalistic imagery, the exhibit was able to overcome immediate conversation stoppers or reflexive resistances of those who, while increasingly uncertain about the morality of the Iraq war, are averse to any idea which requires them to forsake icons and long-held concepts of patriotism.

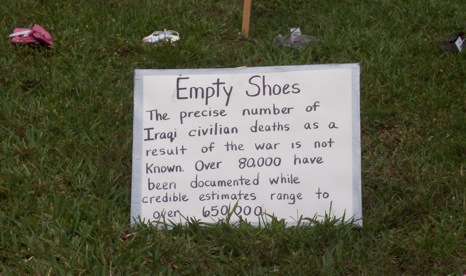

<12> The cross of civilian shoes acted as a walkway which exhibit-goers used to access the exhibit. This design forced exhibit-goers to confront not only the lives lost by American soldiers, but also Iraqi children, men, and women. Aesthetically, the lighter colored tennis shoes stood out from the black boots, creating a bright cross. As a result, the symbolism attracted not only a spiritual understanding of the war, but was also transformed the exhibit into an art exhibit as well as a memorial. Indeed some were attracted to the aesthetic quality of the large grid of 10 rows by 12 rows of a total of 170 combat boots and about 200 tennis-shoes, containing a large white cross. Also, at the back of the black grid of combat boots, in-set with a whitish cross lay a half circle with the remaining tennis shoes representing the civilian deaths. These sets of shoes were sparsely placed so as to not interfere with the cross design. In the space created the memorial utilized research expressed via a sign to put the tennis shoes into context: “Empty Shoes: The precise number of Iraq civilian deaths as a result of the war is not known. Over 80,000 have been documented while credible estimates range to over 650,000.” In this way the exhibit successfully presented not only a Memorial in a Time of War which mourned the loss of American soldiers during a war, but also equally mourned mounting Iraqi civilians deaths.

<13> Like the AIDS Quilt, the Memorial in a Time of war entreats patriotic imagery rather than disdaining it. Specifically, the Eyes Wide Open exhibit featured a set of American flags strategically placed to accent the cross A flag also accompanied a peace wreath at the head of the exhibit’s entrance [22]. At the cross section created by the whitish pathway an a-frame sign proclaimed the exhibit’s name, “Eyes Wide Open.” Whereas American flags and the sacrifice of fallen soldiers are symbols government’s traditionally exclusively lay claim to, the exhibit successfully co-opted and humanized this Nationalistic language, subtly using it to reveal the morbid reality behind often empty patriotic slogans.

<14> Another lever utilized in conveying the cost of the Iraq war, albeit featured far less significantly, was the resources and reward approach. Drawing on estimates from Nobel Prize winning economist, the A-frame sign featured at the arc of the exhibit read: “U.S. taxpayers have already spent more than $1 trillion for the first four years of the war. Every day that the war continues adds another $720 million to the cost of war. Of that total, Florida taxpayers will pay over $39 million each and every day that the war in Iraq continues.” In slightly smaller print on the right hand side the sign read: “Budgetary Trade Offs: What could Florida’s share of one day of war pay for? – 27,781 homes with renewable electricity or – 19,875 children with health care or – 12,767 scholarships for university students or – 5,348 Head Start places for children or – 731 elementary school teachers or – 291 affordable housing units or – 6 new elementary schools.” [23] Beyond utilizing the resources and reward lever, this information clearly appeals to those who appreciate reasonable and empirically based considerations of the Iraq war. Finally, the event benefited from the fact that it took place just one day prior to the fifth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq.

<15> Without a doubt, resonance was one of the key levers to the success of the exhibit. With the help of about six volunteers, the exhibit was unloaded and set-up on the “Free Speech” lawn at Florida Atlantic University by about 11a.m. The exhibit location was in a prominent commons area where countless students pass by over the course of the day. During the event, hundreds of students took time to inspect the exhibit. Some stopped and asked organizers what “this was about.” Despite all students having full knowledge that a war in Iraq was taking place, the sight of combat boots in more than a dozen rows was both startling and confusing. Many were visibly shocked once that the boots represented the dead. A common reaction to the exhibit was general consternation. In this way the Memorial in a Time of War made the Iraq war real in a way that no news report, passionate recitation of statistics, or partisan complaint could.

<16> The exhibit provided a unique opportunity to have a first-hand experience with the perils of the war. Two particularly revealing reactions were published in two different daily newspapers the day after the event. The Sun Sentinel, which is distributed in Broward and Palm Beach counties, featured a large photo of one FAU student crying as she knelt down, books in hand, beside the exhibit, on page three of the local section, March 19, 2008 [24]. The caption read, “Maria Hernandez visits the ‘Eyes Wide Open’ memorial exhibit on the Boca Raton campus of Florida Atlantic University on Tuesday.” Online, the Palm Beach Post featured a five-photo gallery. The first in the photo gallery pictured Josef Palermo. The caption read: “‘I know this guy. I grew up with him,’ said a flabbergasted Josef Palermo after finding the combat boots of childhood friend Cpl. Christopher Poole, Jr., of Mount Dora, Fla.” [25] In Maria Hernandez’s case, the exhibit gave her the opportunity to envision the possibility that her friend(s) might suffer a fate like those being remembered. As for Palermo, the exhibit acted as more than an encounter with the realities of war or the potential perils friends might suffer; it literally delivered the concrete fact that an acquaintance had died as a result of the war. While Palermo was apparently no longer in communication with the soldier or his family, the exhibit succeeded in removing the impersonal veil from the war; it undid the abstract nature of the conflict.

<17> In addition to student observers, a dozen or more college faculty members walked the rows of shoes. In at least one case, a professor took the opportunity provided by the occasion to instruct one of his classes to examine the exhibit and write a short reaction paper. Another professor had wanted to do the same, but her class began when the exhibit had ended.

Memorial in a Time of War as Moral Confrontation

<18> The Memorial in a Time of War confronts exhibit-goers with fundamental moral questions from three different moral approaches. The fundamental facet of the Memorial in a Time of War is that it carries with it a portent of the immediate future. Furthermore, it conveys the understanding that one is obligated to make a moral stand on the issue of the war, and is thus responsible for the future being signaled. Memorials held in a post-war environment honor the dead and mourn their loss without confronting exhibit-goers with a current and character-defining moral decision. The Memorial in a Time of War, as embodied by the Eyes Wide Open exhibit, however, acts as a poignant Moral Confrontation. Indeed, the exhibit implicitly deploys three moral arguments and demands memorial-goers make a moral decision.

<18> First, the Memorial in a Time of War conveys to memorial-goers the consequences of war in terms of blood and treasure. Even those generally disinterested in American foreign policy, when forced to look upon this spectacle located in a public space, cannot help but to be disturbed by its ominous presence. No longer protected by mainstream media blackout on images supposedly bad for “troop morale,” all are confronted with, in the case of the Eyes Wide Open exhibit, literally hundreds of pairs of shoes directly representing a throng of human lives that are no more. Not only do the boots represent thousands of dead American soldiers, many of whom were still teenagers; but memorial-goers are also confronted with the moral morass of seeing children’s shoes representing the Iraqi civilians who are dead as a direct result of the American war; in fact, thousands have been directly killed by American munitions. The Eyes Wide Open exhibit also featured an A-Frame which highlighted the financial consequences of the war in Iraq as well. This of course has moral resonance in that money diverted to the war is money diverted away from education, health, poverty, and housing. Memorial-goers are faced with the questions: has the cost been too great?; is it time we end this war?; or will I remain silent as civilians and soldiers die, and needed resources are diverted away from life sustaining programs in the United States?

<19> Second, the Memorial in a Time of War confronts memorial-goers from the rule-based moral approach. It demands that memorial-goers who believe killing is wrong when not sufficiently justified consider the justification for the war. The Eyes Wide Open exhibit challenged the Bush administration’s moral justification for war based on the idea it would liberate the Iraqi people. In particular, the exhibit emphasized the horrific irony that while our government claims to be liberating the Iraqi people, the empirical evidence shows that a bare minimum of 80,000 to as many as half-a-million innocent Iraqis have died as a direct result of the American invasion. Even if one believes that Iraqis are generally more free since the invasion, though this is not at all bore out by the reality on the ground, one operating from the perspective that killing is wrong must ask: can the deaths of thousands of innocent Iraqi children be justified on the grounds that other Iraqis will eventually become free at some indeterminable date in the future? Moreover, memorial-goers will be forced to ask themselves, is it wrong to sacrifice the lives of American soldiers in a war which has killed many thousands of those the war purportedly aimed to liberate?

<20> Third, the Memorial in a Time of War confronts exhibit-goers with virtue-based morality. Specifically, the Eyes Wide Open exhibit begged the question: how can I, as a moral agent and citizen of a government engaged in waging war, rectify this unsettling, sanguinary affair? In order to end the moral malaise resulting from such a war, one must decide on a course of action: a) support continued military intervention in said war, believing it is the most moral course of action; b) actively participate in opposing continued intervention, believing only an end to the conflict will resolve the matter; c) or some other course of thoughtful action. In any case, those operating from a virtue-based ethic will be confronted with the responsibility of either their action or inaction, and its ramifications.

<21> The Memorial in a Time of War is the quintessential Moral Confrontation. It first conveys to memorial-goers the magnitude of the tragic reality on the battlefield, a reality which is often embellished or obscured in the mainstream media. Then it confronts those with any one of three moral perspectives with the ethical responsibility of considering whether the war is truly right or wrong. Since the memorial takes place during the war and not after, exhibit-goers are left with the full-weight of knowing that their moral decision may at least indirectly impact the future and all that it involves, specifically the life or death of many, many human beings.

Manufacturing Dissent and Critical Debate in the Mainstream Media

<22> One of the most valuable aspects of the Memorial in a Time of War is its ability to communicate with today’s visual culture and thereby get its message publicized via the mainstream media. By generating a great deal of interest from the local press, the Eyes Wide Open exhibit was not only directly experienced by exhibit-goers but indirectly experienced as a community drama by hundreds of thousands of South Floridians watching the news, reading the newspapers, or experiencing the event online. While many progressives believe they have been locked out of the mainstream media because of the content of their ideas, Duncombe makes a strong case that progressives are merely failing to adequately format their ideas to an evolving media. He rejects the contention that the failure of progressives to publicize their ideas to a broader audience is due to their being blocked by corporate controlled media outlets the right. “The archaic concern with formal censorship has little validity in our age of informational overload.” While it is true that government propaganda is a real factor, its success in swaying people has more to do with the realization that “people often prefer a simple, dramatic story to the complicated truth.” [26] In short: “Truth and power belong to those who tell the better story.” [27] The onus, shouts Duncombe, is on activists to generate a viable narrative. Drawing on a James quote, “Truth happens to an idea,” Duncombe calls for progressives to engage in “a propaganda of the truth.” [28] His perspective is bore out in the example of the Eyes Wide Open exhibit, and entreated by the model of the Memorial in a Time of War.

<23> With this reality in mind, the Memorial in a Time of War draws in part on the strategy of media engagement utilized by organizations such as the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). According to Susan Leigh Foster, ACT UP, formed in 1987, designed its protest actions as media spectacles. Foster quotes one of the group’s founding members, Larry Kramer, in saying: “Each action is like an enormous show….” [29] ACT UP directly aimed at presenting a protest which would interest the media, so that the organization could utilize the publicity power of the media to share its message. “In contrast to Civil Rights Protests, ACT UP events were conceived, in part, to attract and utilize media attention to spread the word about their cause.” [30] Foster notes that the organization’s approached the media as a kind of microphone, and “as a social force that sways public opinion, and hence, must be manipulated.” [31] The organization’s success is further testament to Duncombe’s view that progressives are not so much blocked from the corporate media as they are failing to employee successful methods to obtain coverage. More importantly, this work adds to Foster’s analysis of how activists have worked to manipulate the media. Indeed, the media’s coverage of the Eyes Wide Open exhibit is arguably the most successful aspect of the event. Just as redescriptions broadened the audience of exhibit goers by removing resistances to what seems like “anti-American” or “non-Patriotic” protest, such redescriptions removed key resistances for major media outlets, too.

<24> The Palm Beach Post featured an oversized photo, titled “Boots reflect toll of Iraq war,” and brief mention of the event on the front page of the local section, also on March 19, 2008 [32]. The photograph actually showed the organizer (this author) and his daughter kneeling amongst the shoes. The caption read: “Jeff Nall explains the meaning of the empty shoes arrayed at FAU to his daughter Charlotte, 4, Tuesday. They represent U.S. and Iraqi war casualties.” A second photo pictured the boots and tag memorializing Robert J. Wilson, 28, of Boynton Beach, Florida. The caption read: “Rose petals are sprinkled around the boots of Staff Sgt. Robert J. Wilson of suburban Boynton Beach. He enlisted three months after Sept. 11 and died two months ago of injuries from an explosive device while he was on patrol.” On the other side of the photo a brief explanation of the event read: “More than 170 combat boots and 200 shoes were displayed on the grass at Florida Atlantic University Tuesday in an exhibition entitled ‘Eyes Wide Open: The Human Cost of War.’ The combat boots symbolize Florida’s war dead, and the shoes stand for a small fraction of the Iraqi civilians killed in the military and sectarian fighting during the 5-year-old war in Iraq.” Most news stories on the Iraq war have discussed differences of opinions on how the United States should conduct the war, or merely feature the mechanical and often emotionless explication of the latest details on the ground. The exhibit, conversing with visual culture on its own level, gave the mainstream media an opportunity to present a very different way of looking at the conflict. In this way the Memorial in a Time of War allowed the media to humanize its coverage of war, putting imagery to the number of war dead. Moreover, coverage of the exhibit resulted in the rare mention of the civilian death toll.

<25> The Palm Beach Post not only took photos, publishing one in the newspaper and a total of seven online, the paper also assigned a videographer to cover the event. The video, “Eyes Wide Open at FAU,” the two-and-a-half minute video featured interview-narrative by the organizer where he frames the exhibit as an open-ended question. “We wanted to really engage people with the reality, the loss of life that has taken place, on this fifth anniversary of the war.” Later in the video he says: “If you do support the war, this exhibit forces you to really confront the cost of the war; and to really make a really strong decision that you either own this war, or that you realize that you need to stand up against it. And it’s up to you to decide that.” The video shows people walking the exhibit and also features a conversation between an FAU professor and FAU administrator who discuss the civilian loss of life. In the video a 20 year-old elementary education student states: “The saddest part is like you see like the little shoes of nine-months-old kids who died. There nine nine-months-old, they never got to live, they never got a chance to see anything….Which is depressing.”

<26> The exhibit was also covered by NBC’s West Palm Beach affiliate, WPTV. Reporter Paige Kornblue broadcasted live from the school at 6pm, March 18, 2008. Like the Sun Sentinel, WPTV took notice of FAU junior Maria Hernandez’s emotional response to the combat boots she spotted as she walked out of class. She is shown saying, "It brought tears to my eyes right away when I realized what was going on….It struck me when I saw this because I have friends that are being deployed. I have friends that are 18, 19 years old and they have already been to Iraq and when they leave, I don't know that they're coming back.” The story’s most important surprise came when Kornblue, utilizing the description given to her by the organizer, put a rare face to the civilians. “While the boots symbolize the soldiers, the shoes in the middle symbolize civilians. In pairs, together creating a cross, they represent the moms, the dads, the children who have lost their lives in the Iraq War.” While seemingly insignificant, this factual narrative strikes one as particularly rare in the mainstream press. One must ask whether or not such an honest and humane description was the result of the power of the shoes being shaped by a cross, amid the rows of black boots. Interestingly, the report also featured an interview with Kristen Echevarria, whose husband, Chang, a U.S. Army engineer, was currently serving in Iraq. In addition to commenting that the exhibit was hit too close to home, she offered this reflection after looking at the boots: "Some of these kids were 17, 18, and 19 years old... that's a scary thought - that's just a really scary thought," says Echevarria [33].

<27> The success of the Memorial in a Time of War in garnering media coverage is proof that anti-war activists can, in fact, publicize their ideas. The qualification, however, is that in order to do so they must evolve their tactics to today’s visual culture. The Memorial in a Time of War succeeds in attracting media attention because it recognizes the many factors that comprise human consideration of ideas, from Gardner’s levers of mind change to Duncombe’s notion of the propaganda of the truth. First, by presenting the exhibit as a memorial honoring the fallen, event organizers proffered a story steeped in key symbols which resonated with a broad audience. This was enough to attract those with family and friends in the military, as well as a timid media, ever-nervous about appearing to be anything less than perfectly patriotic. While such an approach succeeded in countering traditional resistances; the exhibit’s emotional resonance remained intact and equally challenging. Succinctly put, the mode of the action succeeded in bringing in a broad audience without blunting the intended moral confrontation. When all was said and done, the media had actually assisted in publicizing what turned out to be a surprisingly candid and, at least implicitly critical view of the war in Iraq.

<28> Compare the success of this event in garnering mainstream media attention to that of a similar event held just one day later. On March 19, 2008, anti-war activists donning black clothing, “white plaster masks and placards with the names of the victims” marched from Arlington National Cemetery to the Capitol building. Protestors eventually stopped “in a silent ‘endless war memorial’ in the middle of the intersection of First Street and Independence Avenue.” Capitol police then proceeded to arrest all 34 activists [34]. The event titled “March of the Dead” was organized by New York based group, Activist Response Team (ART). According to reporter Kevin Young, organizer Laurie Arbeiter literally set out to create what we have been describing here as a Memorial in a Time of War. “‘War memorials are usually created after the war is over,’ says Arbeiter, but the current occupations and the so-called war on trror ‘will go on and on unless people take a stand.’” [35] Indeed, this perspective is precisely the value of the Memorial in a Time of War. This event received no mainstream media coverage. Young writes: “Not surprisingly, most of the mainstream press ignored or downplayed these events and their message. The March of the Dead was virtually absent from March reports in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Boston Globe, and articles in all of these papers neglected to mention the 34 arrests there.” [36] The reason for ART’s war memorial is clear: it failed to utilize fundamental levers of mind change such as co-opting key American symbols. This resulted in a media blackout which the proper Memorial in a Time of War succeeds in overcoming. Again, those wishing to see their actions succeed in creating social change ignore key levers of mind change at their own peril.

Memorial in a Time of War in Context

<29> Before concluding it is worth noting how the Memorial in a Time of War fits into the history of memorials. Seen in its historical context, the use of the war memorial by peace activists is both a radical idea and a powerful tool. Historically, war memorials have celebrated war or victory. They have only evidenced an interest in honoring human life in the last two centuries. Not until around the 19th century did memorials go beyond the task of honoring a particular war or battle to baring the names of the war dead. Memorials carrying the names of the dead also began to grow after World War I. In many ways, the evolution of memorials from glorifiers of war to memorials which honor the dead is a rather recent development. Understanding this history, the peace activists’ very act of organizing and enacting a war memorial can be seen as a radical act.

<30> While the Bush administration worked overtime to downplay evidence of the death resulting from the Iraq war, such as censoring photographs of flag-draped coffins; peace activists, using the Memorial in a Time of War, commemorate the lives lost in the war by inviting the public to gather, reflect, shed-tears, remember, and pay respects in a way Bush’s declarations of “support the troops’ sacrifice” failed to.

<31> Moreover, the Memorial in a Time of War takes on a unique characteristic when we consider how, in the hands of anti-war activists, such memorials concentrate on memorializing civilian lives as well. Consider how the Vietnam War Memorial fails to memorialize the more than one million civilians who died as a result of the Vietnam war; or how the Korean War Memorial fails to memorialize the more than two million civilians who died as a result of the Korean war. During the Iraq war, the practice of counting civilian deaths has been taken up by independent institutions such as university research centers (John Hopkins) and groups like the Iraq Body County project. The Eyes Wide Open exhibit has made direct use of the work done by groups like Iraq Body Count, utilizing the organization’s list of victims’ names, gender, and age to memorialize their lives in the United States. If we consider how even the deaths of soldiers have only recently played a significant role in memorials, it is clear just how powerful the incorporation of the civilian dead into memorial is.

<32> Whereas the AIDS Quilt challenged “the hegemony of cultural meaning over the discourse of the family, insisting that people with AIDS were part of the national family,” [37] the Memorial in a Time of War challenges war proponents’ monopolization of patriotism and its attempts to make “pro-war” and “patriotism” synonymous. The Memorial in a Time of War successfully blurs the line between the “patriotic” and the “unpatriotic.” In terms of popular discourse, it is usually unpatriotic to condemn a nation’s war and particularly “anti-American” to address the civilian death toll. Conversely, it is “patriotic” to “honor” the troops and their sacrifice. The act of honoring the troops’ sacrifice traditionally takes place after the war; or is done in an abstract manner which directs interpretations with banal but directive patriotic slogans. The Memorial in a Time of War, however, presents a relatively open-ended space for contemplation. Instead of proclaiming that the war is immoral or illegal or wrongly founded, The Memorial in a Time of War presents a question framed by intuitive thoughts accompanying unnatural death: is the war worth this sacrifice?

<33> By combining a respectful, patriotic honoring of American soldiers who have died, sharing their names, ages, and hometowns, and the presentation of the reality of the civilian death toll, the Memorial in a Time of War gently accuses not so much the nation, but the war itself as having wrought incredible destruction. Moreover, the Memorial in a Time of War’s strategic approach and use of redescriptions creates a unique opportunity to engage in dialogue with those who would otherwise be averse to such an exchange. In the same way the AIDS Quilt embodied a pluralism “that allows for and encourages collective identities that serve political ends,” [38] The Memorial in a Time of War acknowledges that as a military family may wish to support the war their loved one is engaged in, they have at least as much potential interest as the anti-war activist in bringing the conflict to an end.

<34> While some anti-war activists may wish to skip this method of consciousness-raising in order to work on more direct and plainly stated actions, such as protests, marches, and lobbying, the Memorial in a Time of War must be understood as a necessary component of the anti-war activists’ tool-box. Despite one’s opposition to a particular war, activists must continue to bear in mind that the “facts” are not enough and that what is needed is not so much the unearthing of new facts so much as the creative promulgation of the existing reality; in Duncombe’s words, “a propaganda of the truth.” Indeed, while many may oppose the war they may not be truly aware of or adequately understand the most salient reasons for opposing and, perhaps, fighting to end the war in Iraq. The Memorial in a Time of War creates critical opportunities for many to have a first hand experience with the ugly facts of the Iraq war and their own nation’s war policy. Succinctly put, people must be awakened by indignation before they are moved to act. The Memorial in a Time of War succeeds in introducing people to an injustice that at very least begins to lead down a path toward the indignation necessary for political awakening. Before we can whisk the world away to a peace and justice revolution, steeped in the facts of militarism and moral injustice perpetrated by the likes of the United States military, we must begin by telling a good, potent story.

<35> The value of the Memorial in a Time of War to anti-war activists is difficult to underestimate. Specifically, it presents a model to enlarge the movement’s base of supporters and sympathizers, with the long-term aim of increasing the number of people who share its critical view of American foreign policy. More broadly, it provides an answer to the question of how progressives are to deal with the transformation of the public sphere. In fact, the Memorial in a Time of War provides a model which can be more broadly applied to any number of progressive causes such as supporting universal health care. It builds upon the edifice created by the Enlightenment; it takes into consideration the rise of visual culture, the importance of communicating via the spectacle, and the value of additional levers of mind-change which must be utilized in order to create social change. Most importantly, rather than manufacturing consent, the Memorial in a Time of War provides a model for how we can manufacture dissent, propagate the truth, and increase critical discourse.

APPENDIX

PHOTOS OF EXHIBIT

EYES WIDE OPEN: THE COST OF WAR

MARCH 18 2008, AT FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY

BOCA RATON, FLORIDA

Photo One

Photo Two

Photo Three

Photo Four

Photo Five

Photo Six

News Item One

News Item Two

Notes

[1] According to Howard Gardner there are seven key levers to mind change: reason, research, resonance, redescriptions, overcoming resistances, resources and rewards, and real world events. Howard Gardner, Changing Minds: The Art And Science of Changing Our Own And Other People's Minds (New York: Harvard Business School Press, 2006), 15-18. Throughout this work I will frequently reference Gardner’s aspects of mind-change as I believe they are essential to the task of creating social change.

[2] Again, Gardner identifies as two key levers of mind change.

[3] Stephen Duncombe, Dream: Re-Imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy, “Politics in an Age of Fantasy” (New York: New York Press, 2007), 1-2.

[4] Ibid., 6-7.

[5] Duncombe, 5.

[6] Ibid., 6.

[7] Ibid., 16.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Quoted in Duncombe, 16.

[10] Christopher Capozzola, “A Very American Epidemic: Memory Politics and Identity Politics in the AIDS Memorial Quilt, 1985-1993,” Radical History Review 82 (Winter 2002), 92.

[11] Capozzola, 93.

[12] Quoted in Capozzola, 101.

[13] Capozzola, 101.

[14] Ibid., 92.

[15] Capozzola, 95.

[16] Ibid., 94.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., 96.

[19] Ibid., 95.

[20] I was the organizer of this particular exhibit.

[21] See “Photo One” in appendix.

[22] See “Photo Five” in appendix.

[23] See “Photo Three” in appendix.

[24] See “News Item Two” in the appendix.

[25] Palm Beach Post, "Eyes Wide Open: The Human Cost of War," 19 March 2008; accessed online on 20 April 2008: http://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/content/local_news/slideshows/0318FAUiraq/

[26] Duncombe, 7.

[27] Ibid., 8.

[28] Ibid., 20.

[29] Quoted in Susan Leigh Foster, “Choreographies of Protest,” Theatre Journal 55 (2003), 405.

[30] Susan Leigh Foster, “Choreographies of Protest,” Theatre Journal 55 (2003), 404.

[31] Ibid., 405.

[32] See “News Item One” in the appendix.

[33] WPTV News, “FAU Boots,” 18 March 2008; accessed online on 19 March 2008: http://www.wptv.com/news/local/story.aspx?content_id=062b1184-14e1-444d-ac99-ee31eaeb5c94

[34] Kevin Young, “The March of the Dead” Z magazine (May 2008), 13.

[35] Kevin Young, “The March of the Dead” Z magazine (May 2008), 13.

[36] Kevin Young, “The March of the Dead” Z magazine (May 2008), 14.

[37] Capozzola, 99.

[38] Capozzola, 104.

Return to Top»