Reconstruction 11.2 (2011)

Return to Contents»

The “Metalanguage” Of Race And The (Post) 9/11 Moment: Words Never Said / Trimiko Melancon

Abstract: Drawing upon "Mission Accomplished," a commemorative commercial, and Lupe Fiasco’s song and music video "Words I Never Said," this article examines the degree to which these particular texts serve as narratives that speak to the "metalanguage" of race and racialized enactments, especially as these relate to U.S. racial/ethnic/national identity, in (post) 9/11 cultural productions. While each of these texts toys with race, providing a context in which to interrogate (post) 9/11 sensibilities, their engagements of race and racial politics are varied. Read collectively, they illuminate the ways race, its politics, and racial representations in a (post) 9/11 moment are interpolated in cultural productions, strategically though not uniformly, to not only engage and perpetuate, but also reify and sometimes resist fixations on the larger anxieties governing U.S. racial, ethnic, and national identity in an increasingly globalized world. Through an examination of these particular cultural productions, this article calls attention to, and indeed explicates, the conspicuous shifts in race, particularly the politics and "metalanguage" of race, in light of and in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Not only does this moment emblematize an apparent evolution in the constructions and topographies of race, but it is also embroiled with matters of American and U.S. national identity—and indeed "security," broadly conceived—in an increasingly diverse, globalized, and racialized world. What these texts reveal, ultimately, are the hegemonic and systematic ways waging a "war on terror" has functioned, in methodical and metaphoric terms, as a domestic and international warfare against a particular type of racialization—or, more precisely, against ethnic, global, racial, and ethno-religious others.

Key words: race and ethnicity, culture studies, media

As a fluid set of overlapping discourses, race is perceived as arbitrary and illusionary, on the one hand, while natural and fixed on the other.… Race serves as a "global sign," a "metalanguage," since it speaks about and lends meaning to…myriad aspects of life that would otherwise fall outside the referential domain of race. —Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham

<1> In her seminal work on race, historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, in the tradition of scholars theorizing about racial politics, illuminates the complexities of race by locating it as a "metalanguage." As an apparatus that cannot be defined in singular terms as biological, ideological, or cultural—especially divorced of how it is constituted socially and, oftentimes, constructed to approximate "difference"—race and the politics governing it manifest in various ways. While race has indubitably occupied and played a consequential role historically and contemporarily within American society, culture, and politics, broadly and narrowly construed, it is not a transhistorical phenomenon. It has not operated, that is, as fixed and absolute, nor have its manifestations been consistent and identical over time. Yet, race and the politics undergirding it have and continue to operate, both conspicuously and covertly, in American society in ways that call particular attention to the dynamics of power, representation, national identity, and privilege.

<2> Such instantiations, or phenomenon of race, are evident during the (post) 9/11 moment in exaggerated form, as varied seemingly disparate yet interlocking national events and circumstances reveal. From Hurricane Katrina and the catastrophic governmental responses to it to the attacks on immigration policies and aggressive, even fatal, border control measures; from racial profiling and civil rights violations of ethnic and ethno-religious minorities, particularly Muslims and people of apparent Middle Eastern descent, to the contestation of ethnic studies programs nationwide; and from the rise of stateside hate groups and "vigilantes" to the Birther movement and scrutinizing of President Barack Obama putatively because of national origin and religious beliefs (at the crux of which is race, racism, and racial anxiety), all demonstrate that the (post) 9/11 era is one marked by racial upheaval as well as backlash against racialized/ethno-religious others. As such, the (post) 9/11 moment is not constituted by what some all-too-mistakenly characterize as "post-racial" unless that designation is not taken to mean that we have transcended race. Rather, it is indicative of an overt shift in approaches and deployments of race, whereby it relies on a deeply entrenched reclamation of "American-ness": contingent almost always on constructions of "whiteness," methodically, as emblematic of an "authentically" American identity that relies on racialized (and gendered) others—as less than "legitimate" and disempowered—for sustenance [1]. These "words never said" and racial sensibilities, as they pertain to U.S. national identity, have reached heights unparallel, so much so they are inscribed in and operate as a "metalanguage," explicitly and implicitly, in ubiquitous form in contemporary cultural productions.

<3> Drawing upon two separate and varied texts—"Mission Accomplished," a commemorative commercial, and Lupe Fiasco’s song and music video "Words I Never Said"—this article examines the degree to which these particular texts serve as narratives that speak to the "metalanguage" of race and racialized enactments, especially as these relate to U.S. racial/ethnic/national identity, in (post) 9/11 cultural productions. While each of these texts toys with race, providing a context in which to interrogate (post) 9/11 sensibilities, their engagements of race and racial politics are varied. Read collectively, though, they illuminate the ways race, its politics, and racial representations in a (post) 9/11 moment are interpolated in cultural productions, strategically though not uniformly, to not only engage and perpetuate, but also reify and sometimes resist fixations on the larger anxieties governing U.S. racial, ethnic, and national identity in an increasingly globalized world.

<4> As Alfred López argues with regard to race, 9/11, and the new "postglobal" literature, in the "aftermath of each of the global cataclysms" and 9/11 markedly, "the disenfranchised and marginalized…are most vulnerable to the vicissitudes of increasingly volatile global markets and bear the brunt of the suffering when things inevitably go wrong" (510). While he insightfully recognizes this phenomenon, far more can and indeed should be extrapolated and extended to texts, both literary and non-literary alike, to explicate with more specificity the strategic use of marginal and disenfranchised individuals and groups. That is, not only do such individuals suffer "when things inevitably go wrong" but, more specifically, it is the "marginalized and disenfranchised" that are cast precisely as that which is inevitably wrong in much of the (post) 9/11 cultural productions and propaganda. This seemingly incessant "wrong-ness" translates into various sensibilities: that, as racialized others, they are "outside" and, oftentimes, in opposition to what is authentically American; "wrong" in that they become embodiments of "the problem," in the Du Boisian sense, where race (or "the color-line"), consciousness, and national identity are concerned; "wrong" to the extent they are rendered as intrinsically suspect, threatening, and antithetical to legitimacy and progress; and "wrong" in that they must function almost always as emblematic of difference that necessitates "fixing" on the one hand, yet operate (and is requisite) to approximate particular castings or enactments of "whiteness" on the other [2].

<5> This is not at all to suggest that whiteness functions as analogous with the monolithic or is reduced to a particular homogeneity. Nor does it insinuate that whiteness functions outside the categories of race but, rather, that it largely operates and manifests in a capacity that appears as if it is "normative," "deracialized," and/or authentic. Moreover, it eludes and at times also undergoes, as well as elicits, interrogation in (post) 9/11 cultural productions, where it does not go entirely uncontested. As such, it encapsulates and operates off power, authenticity, and privilege, yet concomitantly resists and becomes a conduit (in relation to racialized others) by which to interrogate these. "Mission Accomplished" and "Words I Never Said" help illumine, then, the degree to which race in the (post) 9/11 moment is not only used as a means of attack but is, at the same time, under siege in a similar vein as that of the World Trade Center, Pentagon, and America itself.

"Reading Race and the Difference It Makes": (Post) 9/11 Cultural Productions

<6> Historian Barbara Fields argues that race is not natural, and therefore embodies a particular artificiality—and thus race should be interrogated to expose its functions and persistence, and indeed its prolongation, in particular contexts [3]. An examination of (post) 9/11 texts and cultural productions warrants an analysis of the functionality, as well as strategic deployment of race. To this end, race might be understood, or at the very least read, as an apparatus created and utilized to maintain power structures, demarcate difference, or respond in the reformative sense—to revert to Michel Foucault—to particular exigencies of a cultural, economic, or socio-political nature [4]. This is especially apparent in the (post) 9/11 era when race is utilized/manipulated, at times deliberately and systematically, to produce and solidify a particular type of narrative regarding U.S. identity, broadly construed, domestically and abroad.

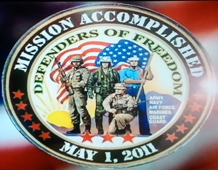

<7> With this logic and understanding in mind, I turn now to the "Mission Accomplished" commercial, an advertisement (which first aired in May 2011 after the capture of Osama bin Laden) that seeks to commemorate 9/11 and the "war on terrorism." At the onset of the commercial, a deeply patriotic masculine voice honors the United States Military for bringing Osama bin Laden "to justice." In commemoration of the moment, the announcer segues from laudatory remarks into an advertisement for a "Mission Accomplished United States Coin" (Figure 1), constituted by a troop from each respective branch of the military in uniform, with artillery in hand, against the backdrop of the American flag and the insignia, "Defenders of American Freedom" (Figure 2).

|

|

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Mission Accomplished Commercial (American Coin Treasures, 2011) | Figure 2. "Mission Accomplished" Coin (American Coin Treasures, 2011) |

<8> The coin itself is $19.95 plus $5.95 shipping and handling, limited five per customer, with the first 250 customers receiving a free American flag lapel pin. Five dollars of each purchase will be donated to the "Special Operations Warrior Foundation," honoring families of "fallen heroes." As the announcer recapitulates, "It’s the patriotic duty of every American to keep the memory of these events alive. Do your part. Call now." Beyond the extent to which the advertisement capitalizes off of bin Laden’s demise for commercial purposes and invokes an imperative sense of patriotism, it aligns one’s allegiance and measures one’s "American-ness" through a consumerism that is as tenuous as its representations of American identity, national and militaristic, are contentious.

<9> The face of America and its citizenry, vis-à-vis its troops, is steeped in racial and gendered terms—as undeniably white and indisputably masculine—to the extent these appear fixed like a naturalized trope. That is, this naturalization of white masculinity and male whiteness operate as not only "normative," but inextricably "American" as well. Furthermore, when the faces of the American families that should pass on the stories, as well as the commemorative coins to "their children and grandchildren," are white, these individuals, like the troops from the varied military branches, serve as a microcosm of America in terms that are skewed, exclusionary, and illusive. These associations, seemingly nuanced yet pronounced, of what constitutes and engenders American identity, citizenry, "authenticity," and allegiance might go unnoticed, as indeed credulous and legitimate, by an otherwise general and largely unsuspecting American viewing audience. This, in part, is what makes the commercial, specifically the ideologies and sensibilities undergirding it, all-the-more deleterious. It is subtle and undetectable by some, transparent to others, but deeply inculcating nonetheless.

<10> What the advertisement illuminates, moreover, is the extent to which America (whether in terms of nationalism, identity, or democratic freedom) is defined in association with warfare, weaponry, and military dominance, alongside hegemonic white masculinity—a combination that in sum invalidates and fails to acknowledge "others" as first-class, legitimate citizens or generally. In other words, race and U.S. national identity, as well as 9/11 (and the militaristic assassination of bin Laden), are manipulated, resulting in a totalizing effect that inevitably obscures and privileges white masculinity as intrinsic and constitutive of American freedom, democracy, and identity.

<11> The commercial later repeats the (post) 9/11 mantra "Never Forget," under which is inscribed "The United States of America," in a shot wherein three fire fighters and police officers, as representative rescue workers, raise the American flag out of the ashes of Ground Zero. In a move apparently intended to memorialize the moment and its essence, this image relies heavily on sensibilities and a narrative, at once ideological and aesthetic, steeped in illusions on the one hand, and omissions on the other. What ultimately reverberates, whether deliberate or inadvertent, is a (re)entrenchment of the conviction that the American Republic was putatively founded by and remains the property of white men seeking "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." This, in turn, translates in this commercial into a commemoration of this notion: to "never forget" the degree to which these ideals and nation—conceived/inscribed through images and representations in the advertisement as "theirs"—will be protected at all costs (from $19.95 to that which cannot be quantified). What ends up propagated, regardless of the commercial’s motivation, is a claim to and indeed reclamation of America in strict and rigid racial, gendered, and nationalistic terms. Nationalist sentiment or nationalism, as Ernest Gellner reminds us, "is primarily a political principle, which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent" (1). This very "congruency" is enacted in "Mission Accomplished" whereby the American nation, while appearing seemingly neutral, is constructed in white, masculine, militaristic terms—as "natural" and "normal"—to emblematize U.S. national identity, freedoms, citizenry, and loyalty.

<12> Much like the "Mission Accomplished" commercial, the pop-infused hip hop performance "Words I Never Said" offers another (post) 9/11 narrative. While "Mission Accomplished" addresses 9/11 and the "war on terrorism" in a relatively codified fashion as commercial advertisement, Lupe Fiasco’s song and accompanying music video, in a polemical anti-establishment style, are far from nuanced and are, indeed, explicit and controversial in their engagement with 9/11, as well as the domestic and international consequences that ensued in its aftermath. Seemingly race neutral, "Words I Never Said" (by lyrical artist Lupe Fiasco, a black Muslim whose government name is Wasalu Muhammad Jaco), both illuminates and challenges U.S. national identity in a globalized world, particularly as this intersects with a politics of silence—the "words I never said"—as it pertains not only to the U.S. government but general American public in a post-9/11 context. In the song/video, silence manifests in myriad ways and has varied meanings. In a post 9/11 era, and particularly when one’s allegiance is constructed through an unquestionable support of the government, silence (or not speaking out in protest) becomes emblematic of American patriotism that crosses racial, gender, and class lines and solidifies one’s national loyalty. In "Words I Never Said," Fiasco dismantles such sentiments, illuminating the extent to which silence is neither patriotic nor authentic "American duty" but, rather, acquiescence, entrapment, and contrary to U.S. democratic freedom. "Words I Never Said" destabilizes, or at the very least challenges, such thinking by calling attention instead to what lies behind such silence.

<13> The song opens with a chorus by vocalist Skylar Grey singing, "It’s so loud inside my head / With words that I should have said! / As I drown in my regrets / I can’t take back the words I never said." This "hook" in the video is punctuated by Fiasco, in black combat boots, approaching a commuter bus filled with passengers of various demographics—ranging in race, ethnicity, gender, and age—muffled with mouth contraptions that appear, at once, to prevent and protect: to silence speech while also covering the passageways to seemingly shield passengers from exposure to airborne contaminants (another specter of 9/11). This scene is richly symbolic, emblematizing ambiguity and a fine line between agency (self-imposed silence) and censorship (government imposed regulation against speaking out or First Amendment rights). Against this backdrop, Fiasco walks to the back of the bus, starring at passengers in ways that are piercing, before taking control of the loudspeaker, through which he makes controversial statements regarding the "war on terrorism" as a moment marked by everything from omissions of truth, governmental retaliation, and warfare against globalized and ethno-religious subjects to "cover-ups" under the guise of U.S. national security against terrorist regimes. Not only does this call into question who and what constitutes a "terrorist," but it also underscores the consequences of terror that is endemic and deeply entrenched in (post) 9/11 America. Moreover, he also flips the proverbial script in going to the back of the bus, though not in a Jim Crow (segregationist) capitulation to U.S. domestic racial apartheid and inequalities, especially with regard to racialized others and blacks/African Americans specifically. Instead he raises his voice, in a refusal to succumb to silence, oppression, or repression in a demonstration that the "revolution will be lyricized" [5].

<14> In an opening verse ranging from allegations of conspiracy theory to uncensored indictments against the U.S. government and its militaristic response to 9/11, Fiasco breaks the proverbial silence in a lyrical diatribe:

I really think the war on terror is a bunch of bullsh*t

Just a poor excuse for you to use up all your bullets

How much money does it take to really make a full clip

9/11 building 7 did they really pull it

Uhh, and a bunch of other cover ups [6]

Refusing to capitulate to silence, Fiasco not only delegitimizes the "war on terror," but speculates about a nexus of militaristic violence and voyeurism, whereby the "war" is reduced to a guise to kill—or "use up all your bullets"—by unspecified referents and an undifferentiated "they." This leads to an ambiguity, whereby "they" resonates without specificity and, conceivably, characterizes the government on one hand, or Al-Qaeda on the other. Given the reference to "cover ups," one might surmise the former—in a move that is controversial at best and treasonous at worst.

<15> The verse becomes far less nuanced and codified, however, when Fiasco, in a castigatory move, criticizes the news and "figureheads" for their negligence in "blabbering" when they should be "telling us the truth." As such, he spews out that "[Rush] Limbaugh is a racist / Glenn Beck is a racist / Gaza strip was getting bombed, Obama didn’t say sh*t." Whereas race and racial politics had, otherwise, been seemingly neutral, Fiasco demonstrates the extent to which in a (post) 9/11 era, racial backlash is ubiquitous, so much so that conservatives Limbaugh and Beck, who are well-known for their overt (public) political incorrectness, racial insensitivity, and conspicuously racist remarks, are "called out." In this regard, their public antics, which largely rely on (post) 9/11 anxiety where race and racialized others are concerned, are controversial and reprehensible. Yet, in a deployment of white male privilege, as well as manipulation of their power and subject position—which is especially "normalized" as authentic, acceptable, American, and politically correct (post) 9/11—they make egregious commentaries regarding racialized others with relatively little punitive measures.

<16> This indictment of privilege and white hegemonic masculinity, as well as exploitation of power/duty (during a racially/nationally fragile post-9/11 moment), is juxtaposed with Barack Obama, whom Fiasco disparages not for racist antics but, rather, for an ostensible neutrality—or, what Fiasco recognizes as "silence"—on the international issue of the Gaza Strip. This, Fiasco deems, in a hyperbolic stance, as equally, if not more dangerous: "I think the silence is worse than all the violence." As such, in not speaking up, one, if even and perhaps especially the President himself, inadvertently becomes, as Fiasco avers, an accomplice to the crisis and, therefore, partially responsible for it [7]. Moreover, in a move that overturns what constitutes "the problem," Fiasco identifies himself as "part of the problem" not by virtue of his subject position as a racialized, ethno-religious other (black and Muslim) but, rather, because he is "peaceful" and "believe[s] in the people." To this end, he disrupts and challenges (post) 9/11 politics of racial backlash that would, otherwise, cast(igate) the marginalized and disenfranchised—including himself, a young black male Muslim—as "the problem" or what is inevitably wrong.

<17> The song further dovetails into concentrated focus on ethnic and ethno-religious dynamics, in terms of the Gaza Strip, and the attack on Muslim identity and Islamic religious practices, which are deeply misconstrued, he argues, in the aftermath of 9/11. In a gesture that is as didactic as it is corrective and politically charged, Fiasco destabilizes stereotypical and skewed (extremist) associations with Islam:

Now you can say it ain’t our fault if we never heard it

But if we know better than we probably deserve it

Jihad is not a holy war, where’s that in the worship?

Murdering is not Islam!

And you are not observant

And you are not a muslim

Israel don’t take my side ‘cause look how far you’ve pushed them

Fiasco delineates what he recognizes as consequential and fundamental tenets of Islam in an effort to subvert mythologies and (post) 9/11 conflations of Muslim identity and Islamic worship with terrorism and "holy war." His differentiation, nuanced but overarching, is between the peaceful practicing worshippers and extremists who are non-representative of the Islamic faith. Yet, these get manipulated in an era of racial anxiety to the extent racialized and ethno-religious subjects are associated with violent extremities and terrorism, which invariably leads to violations against their civil rights that are deemed "justifiable" for the overall protection and betterment of the American nation, under the designation "war on terrorism" [8]. As a mystical framework, "the war on terror," as Michael Welsh avers, generates varied dynamics and dichotomies along varied lines (racial, national, religious, ethical), as well as produces an environment wherein violence against what is deemed dangerous, threatening, and evil is accepted. Not only does this undermine sensible counter-terrorist actions, but also, he further posits, "victimize[s] scapegoats, that is, people not associated with political violence but [who are] nonetheless targeted merely because of their ethnicity and religion, namely Middle Easterners, Arabs, and Muslims, as well as South Asians" (4). In turn, violence and aggression are displaced onto these (and other racialized/ethno-religious others), who become targets—and the embodiments of "the enemy" and approximations of difference—precisely because of their race/ethnicity, nationality, and religious affiliations, among other (identity) politics.

<18> Fiasco’s lyrics, read within this context, take on loaded meanings steeped with complexity: that is, his verse singlehandedly indicts those who inflict violence and decimate in the name of faith/"holy war." Yet, it is also a scathing critique of non-Muslim subjects (a general public and U.S. government) who are not "observant" in their ill-conceived notions and internalized mischaracterizations of Islam that lead to the essentialization of Muslims as terrorists; and, equally problematic, lead to an agglomeration of Middle Easterners collectively, ignoring fine distinctions concerning ethnicity, race, nationality, or particular stances toward violence and terrorism.

<19> "Words I Never Said" illuminates and contests, then, the extent to which race, as well as ethno-religious practices and sentiments, are systematically constructed and distorted (post) 9/11. What it calls attention to, in part, are not only the paradoxes of race in America, but also the degree to which the politics and topographies of race are constructed/mediated, especially since Middle Easterners are categorized in the U.S. (by government systems of racial classification) as officially "white." While this may be the case in governmental terms, it most certainly is not at all the case in practical terms. For as John Tehranian argues, "despite the formal classification of Middle Easterners as white, the sinuous and tortured racial status of Middle Easterners is not only ambiguous but a conundrum subject to the vicissitudes of time" (38). This is especially so in the (post) 9/11 period, in which they are racialized as the antithesis of "whiteness" while, in formal/technical terms, are concomitantly classified as "white." To this end, they do not embody whiteness, in the conventional sense especially in a (post) 9/11 era but, rather, they are utilized to fortify particular deployments of whiteness in the age and aftermath of 9/11.

<20> What "Words I Never Said," as does "Mission Accomplished," call attention to ultimately are the conspicuous shifts in race, particularly the politics and "metalanguage" of race, in light of and in the aftermath of 9/11: the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. Not only does this moment emblematize an apparent evolution in the constructions and topographies of race, but it also is embroiled with matters of American and U.S. national identity—and indeed "security," broadly conceived—in an increasingly diverse, globalized, and racialized world. Moreover, the texts, individually and collectively, speak to the hegemonic and systematic ways waging a "war on terror" functioned, in methodical and metaphoric terms, as a domestic and international warfare against a particular type of racialization—or, more precisely, against ethnic, global, racial, and ethno-religious others. This takes shape in varied nuanced and far more transparent forms, whereby "authentic" American identity is invariably transposed and projected onto a citizenry, as well as patriotism, largely defined against and in opposition to the historically marginalized and disenfranchised and almost always in relation to "whiteness." And so, while whiteness indeed "remains as elusive as ever," it—along with race and politics governing it and U.S. racial/national identity—also, paradoxically, remain intact and concrete post-September 11, 2001.

Notes

I would like to express my gratitude to Reanna Ursin, Cathy Schlund-Vials, and Keisha-Khan Perry for their invaluable feedback and intellectual support, as well as extend special thanks to Sandra Duvivier for her exceptionally noteworthy insight.

[1] My use of "whiteness" and how it is deployed in (post) 9/11 cultural production is not at all to suggest that whiteness is not a race but, more precisely, that it operates and manifests in a capacity as if it is, indeed, "normative" and "un-raced" to the extent it oftentimes appears to have altogether transcended the category of race.

[2] In his explication of race and "double-consciousness," as it pertains to blacks specifically, Du Bois relies on the fundamental issue of "How does it feel to be a problem?"—which undergirds his theorization of race, "the color line," and the dialectic of being black and American. As racialized others, blacks were positioned as "the problem" in a system of racial hierarchies and oppression by virtue of their blackness in an American society wherein "whiteness" was conflated with authentic American-ness. While Du Bois makes his assertion at the turn of the twentieth century and explicitly in relation to African Americans, his argument can be extended beyond this timeframe and is applicable to racialized others in a (post) 9/11 moment. See The Souls of Black Folk, 213, 215.

[3] For further explications of race, its functions, and the "racial contract," see also Gates, Higginbotham, and Mills, respectively.

[4] See Foucault, Power/Knowledge.

[5] My comment here alludes to Gil Scott-Heron’s "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised."

[6] These and all subsequent transcribed lyrics to "Words I Never Said" derive from Direct Lyrics: http://www.directlyrics.com/lupe-fiasco-words-i-never-said-lyrics.html

[7] For additional commentary on his disenchantment with government, as well as his characterization of Obama as emblematic of American government past and future, see his CBS News "What’s Trending" interview (7 June 2011).

[8] For further discussion of violations of civil rights, see Hagopian.

Works Cited

Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk. 1903. In Three Negro Classics. New York: Avon, 1999.

Fiasco, Lupe. Interview by Shira Lavar. What’s Trending. CBS. 7 June 2011.

---."Words I Never Said." LASERS. Atlantic Records 1st & 15th, 2011. CD.

---. Words I Never Said. Dir. Sanaa Hamri. Atlantic Records 1st & 15th, 2011. Music Video.

Fields, Barbara. "Ideology and Race in American History." Region, Race, and Reconstruction. Eds. J. Morgan Kousser and James M. McPherson. New York: Oxford UP, 1982. 143-47.

Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings. Ed. Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon, 1980.

Gates, Henry Louis. "Introduction: Writing ‘Race’ and the Difference It Makes." "Race," Writing, and Difference. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1986.

Gellner, Ernest. Nations and Nationalism. Itacha, NY: Cornell UP, 1983.

Hagopian, Elaine C, ed. Civil Rights in Peril: The Targeting of Arabs and Muslims. Chicago: Haymarket; London: Pluto, 2004.

Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. "African-American Women’s History and the Metalanguage of Race." Signs (Winter 1992): 251-274.

López, Alfred J. "‘Everybody else just living their lives’: 9/11, Race, and the New Postglobal Literature." Patterns of Prejudice 42: 4-5 (2008): 509-529.

Mills, Charles W. The Racial Contract. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1997.

Mission Accomplished United States Coin by American Coin Treasures. Advertisement. www.MissionAccomplishedCoin.com. 24 May 2011. Internet.

Tehranian, John. Whitewashed: America’s Invisible Middle Eastern Minority. New York: New York UP, 2009.

Welch, Michael. Scapegoats of September 11th: Hate Crimes and State Crimes in the War on Terror. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2006.

Return to Top»