Reconstruction Vol. 11, No. 4

Return to Contents»

The Muslim-American Neighbour as Terrorist: The Representation of a Muslim Family in 24 / Rolf Halse

Abstract: Academic literature on movies and TV—serials produced in Hollywood documents that Muslim and Arab characters are often represented in a stereotypical and negative manner. The TV-serial 24 doesn’t seem to be an exception. 24 has been accused by Muslim interest groups in the US and by prominent people with Muslim background for stereotyping Muslims. This article sets out to investigate whether this accusation is well founded by analysing how a Muslim family, living in Los Angeles as a sleeping terror cell, is represented in the serial. A textual analysis uncovers a change in the Muslim stereotype in US TV— entertainment post-9/11 having to do with the stereotype’s relocalization. The new Muslim stereotype seems to resemble the average American’s appearance, which, in effect, redefines ‘the Muslim other’; on the outside it differs from the traditional Muslim stereotype, but within, in its character it is true to type.

Keywords: Representation, serial TV—drama, character analysis, stereotypes, Islamic terrorism, the Muslim other

"Our Arab at his worst is a mere barbarian who has not forgotten the savage. He is a model mixture of childishness and astuteness, of simplicity and cunning, concealing levity of mind under solemnity of aspect […]. His acts of revolting savagery are the natural results of a malignant fanaticism and a furious hatred of every creed beyond the pale of Al-Islam."

— Sir Richard Burton, a Victorian Orientalist, famous for his travels in the Middle East and for his translation of The Arabian Nights (cited after Tidrick 1989: 83).

<1> Films and television series from Hollywood have been accused of disseminating negative and stereotype images of Muslims and Arabs. Scholarly work on representations of fictional Muslim and Arab characters confirms that they often have been thus portrayed thus in Hollywood productions (Shaheen 1984, 2001; Semmerling 2006; Woll & Miller 1987). The TV serial 24 (Imagine Entertainment/20th-Century Fox, 2001-2010) doesn’t seem to be an exception. Muslim interest groups in the US have criticized the show for its portrayals of Muslim characters (Parry 2007, Bakhsi 2007). In addition, prominent Muslim and Arab figures like the media researcher Jack G. Shaheen (2008), the actors Shaun Majunder and Maz Jobrani, Queen Rania of Jordan, and even the Turkish embassy in the US, share a critical view of the serial’s depiction of Muslims and Arabs.[1]

<2> In a typical episode of 24 four or five stories are told simultaneously, and the transitions between storylines are sharp and quick-paced, as in most contemporary US quality TV-serials. However, 24 applies an innovative storytelling technique which sets it apart from the rest: a ‘realtime’ approach to programme making, where one episode equals one hour of life in the show’s diegetic world. This technique requires events in 24’s narration to unfold within a twenty- four hour time frame. 24 is probably the first TV-serial ever named after its storytelling technique, rather than in reference to its diegetic world.[2] The limited timeframe affects and restricts how characters are depicted in the show.[3] Character portrayals become more a reflection on the immediate consequences of the characters’ individual and often limited actions than in serials which are more at liberty to recount the characters’ background and development.[4] Some of the characters appear in more than one season, but the majority, especially villains (who have minor roles in the show), partake generally in only a few episodes in the course of a season. Terrorists are evil characters in 24, and their on-screen appearances typically serve a limited number of narrative functions which they normally fulfil in the storyline. They lurk behind and set in motion sequences of terror; they kidnap, threaten, blackmail and murder. Terrorists occupy a limited space in the storyline, and are often characterized by few and distinctive traits, which makes them easily identifiable.

<3> This paper investigates Muslim characters that constitute the enemy forces by presenting a study of a Muslim family in season 4 of 24. A textual analysis that penetrates the serial’s original manner of storytelling (the organization and style of the narrative) examines the storyline of the family, focusing on how they are portrayed. The crux of the analysis centres on whether, and if so — in what respects the representation of the family is stereotypical. The story’s plot and the family’s character traits are studied in relation to various documented categories of Muslim stereotypes in Western popular culture.

Views on the stereotyping of Muslims in 24

<4> The Council on American-Islamic Relations, American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee and the Muslim Public Affairs Council have accused 24 of representing Muslims in a manner that fuels intolerance and prejudice (Kanfer 2007; Parry 2007). These Muslim interest groups have protested against Seasons 4 (2005) and 6 (2007) of the serial, in which Islamist terrorists were depicted as evil villains and cultural "others". When Season 4 was broadcast on TV—stations in the United States, the serials’ creators and producers met harsh criticism concerning the representation of a terror cell as an ordinary Muslim American family. Indeed, Fox Network Television promoted the season with the slogan, "They could be next door". The storyline upset many Muslims in the US (CAIR Chicago 2005; DiLullo 2007: 17), and initiated a broader debate about how Muslims and Arabs are portrayed in 24.[5] Fox responded to the criticism by announcing an offering of public service announcements during the season on local television stations in the US, funded by CAIR. Fox cooperated with CAIR to produce spot announcements in which Kiefer Sutherland cautioned the show’s viewers not to stereotype Muslims.[6]

<5> Co-creator and executive producer Robert Cochran claims that they did not alter the contents of Season 4 despite the controversy about the representation of the family as terrorists, because the representation was balanced. He explains that at the beginning of the season, it may have seemed like we were doing the "stereotype thing", but that was not the case. According to Cochran, the creators of the serial did not produce three stereotype terrorists: ‘One of them is unwaveringly stuck to the cause. One of them, the kid, decided it was too much when he saw someone die in front of him, […] the mother was caught between (DiLullo 2007:17). Co-producer and director, Jon Cassar, emphasizes the importance of portraying characters with depth. The expensive and impressive action scenes do not entirely define the serial. Cassar states that he is tired of 24 always being called an action show, because it is based on real characters, with an aim to make the villains three-dimensional: "Making the evil terrorists seem real has long been a challenge because they are real people with their own point of views" (DiLullo 91)[7] Cassar believes that in Season 4 they have managed to base the enemy — i.e., the Araz family — in reality better than in previous seasons. He also explains what is scary about portraying a normal Muslim American family as terrorists:

I remember shooting the very first scene with them sitting at the kitchen table arguing about family stuff, it wasn ’ t even about them being terrorists, and we are watching the carnage of the train wreck they cause as they are sitting there calmly eating breakfast […] you think this could be my neighbour or the guy down the street. To me, that is much scarier than a nuclear bomb hitting LA, because you can’t get your head around that (DiLullo 2007: 91).

Stereotypes

<6> Stereotypes are commonly understood as simplified, generalizing characterizations of a group of people. Walter Lippmann (1991: 96) defined a stereotype as "the projection upon the world of our own sense of our own value, our own position and our own rights". Two diverging understandings of Lippmann’s conceptualization can be elucidated. On the one hand stereotypes are both deficient, biased, and in the interests of those who apply them. On the other hand stereotypes are a means to ensure efficient information processing. The existence and utilization of stereotypes can thus be explained and understood both from the viewpoint of the dominant forces "need to create and sustain structures of inequality and power, and from individuals" need for economizing cognitive processes.<7> Stereotypes operate as distancing strategies that place others so as to point up and perpetuate certain normative boundaries for social conduct, roles and judgements, thus distinguishing what is threatening and disturbing from what is regarded as acceptable and legitimate (Pickering 2001: 174). A rise in ethnic and racial stereotypes usually accompanies a rise in conflict and discontent in a society. Stereotypes offer explanations of negative experiences and developments in a society, such as escalating unemployment and crime rates, and present mechanisms for dealing with them. Take, for example, terrorism, which increasingly has become a problem for Western countries. That most terrorists are Muslims from the Middle East is a popular truism these days. When Western media discourses represent Muslims using stereotypes, Muslims can to a greater extent be distanced from ’us’. The threat and the fear that terrorism evokes can thus be identified with Muslims, which in turn can attempt to be controlled by distinguishing Muslims as a group and reducing the group’s diversity to a few observable traits they are alleged to possess.

<8>In audiovisual fictions, media stereotypes are a particular subcategory of a broader category of fictional characters; the type. The type does not change or develop during the course of the narrative, and it points to general, recurrent features of human activity. Richard Dyer (1977: 29) distinguishes between social types and stereotypes. Types are instances which indicate those who live according to the rules of society (social types) and those whom the rules are designed to exclude (stereotypes). In narratives, social types can be utilized in a much more open and flexible fashion than stereotypes. They can figure in a wide range of plots and possess a diversity of roles. In films and in TV serials stereotype characters are efficient and economic narrative devices. When presented on screen, they spell out the category of people one is dealing with, for example by a certain body language (like mannerism and gestures) or clothing codes. Film and television creators can thus spend less time on introducing the character.[8]

Research on Muslim characters in Hollywood’s film and TV—series

<9> Historical and textual analyses of representations of Muslims and Arabs in US TV series and films demonstrate that they have been portrayed in a negative and stereotypical manner (e.g. Shaheen 2001, 2008; Fuller 1995). Research points out interesting historical differences in the material (Eisele 2002; Michalak 1988). Michalak examined two reference catalogues produced by the American film industry ‒ one for films from the 1920s and one for films from the 1960s. An analysis of the themes of the films in the reference catalogues finds that even though the Middle East had changed, the Arab stereotype was still more or less the same. It also documents that Hollywood’s "Middle East" had to a stronger degree become a sinister place (Michalak 1988: 32). Primary stereotypes of Muslims in Western culture can be divided into four core images: "violence, lust, greed and barbarism" (Karim 1997: 157). Variations of these stereotypes in Western popular culture are that Muslims have immense, but ignoble and undeserved wealth, they are barbaric and regressive, indulge in sexual excess, and are prone to violence (Karim 2003: 62; Shaheen 1984: 4). Such traits have long formed the core of dominant European perceptions of Muslims and Arabs, deriving from cultural traditions dating back to the Middle Ages. The expansion of Islam into Europe in this period set Europeans against Muslims and led to Western political and cultural efforts to discredit Islam and Islamic culture.<10> Jack G. Shaheen began documenting images from entertainment shows on TV in the US in 1974, and his findings suggest that Muslim Arabs have often played the role of villains and cultural ’others’. Shaheen (1984: 4-5) lampoons the image that fits most Arabs depicted on TV with what he calls ‘The Instant TV Arab Kit’, which consists of a belly dancer’s costume, a turban, a veil, sunglasses, flowing dresses and robes, oil wells, limousines and/or camels. Shaheen (2008) also discovered a new phenomenon in the 2002/03 US TV season. Here, the US network producers introduced a new threatening Arab stereotype: the Muslim Arab-American Neighbour as Terrorist. Shaheen has since documented over 50 programs from the US culture industry which pipelines this mythology into people’s living rooms. He also states that almost half of all Americans are reluctant to have Arabs or Muslims as their neighbours (Shaheen 2008:49).

<11> In all fairness, there are also scholars who rebut with the accusation that Hollywood is stereotyping Muslims and Arabs. Daniel Mandel (2001: 19-20) believes that media scholars and Muslim interest groups have lobbied vigorously and criticized in public what they believe are distortions. Mandel asserts that these critics have three key complaints: first, that Islamic violence is distorted, second that Islamic terrorism is invented, and third that Muslims and Arabs never get to appear in sympathetic roles. However, Mandel (2001: 27) finds it only natural for Hollywood action films to deal heavily in stereotypes. The way in which an action film tells stories is greatly influenced by the success attained in choosing protagonists and antagonists. Mandel stresses that Hollywood’s use of stereotypes usually has basis in fact. After all, he asks, are not many anti‒ American terrorists Muslims or Arabs?

24 and the action TV genre

<12> 24 is difficult to classify, as it appears to be a hybrid of several genres. The serial’s portrayal of emotionally charged scenes, with intimate dialogues between lovers, family members or colleagues at the Counter Terrorist Unit (CTU), makes 24 at times reminiscent of prime-time soap operas. 24’s insistence on realism, the illusion of being broadcast live and its videographic style also draws it towards the TV genre of drama-documentary. Nevertheless, it is most likely that 24 should be categorized within the TV genre of action series/serials. Usual elements incorporated in a story in the crime genre, a sub-genre of the action series, are: a law is broken (Season 4 starts with Muslim terrorists arranging a major train collision); the authorities discover this; the hero and his colleagues try to discover why and how this happened and who is responsible. They encounter informants and villains; combating the enemy’s rank and file. Ultimately, the arch‒ villain is revealed and defeated in a grand battle scene. After a shoot-out, the hero Bauer manages to catch the ‘super‒terrorist’ Marwan, but he commits a martyr’s suicide. A concluding sequence restores the equilibrium (Miller 2001: 18). Other characteristics 24 has borrowed from the crime genre are the tension created by viewers being kept in a constant state of limited knowledge and suspense and the use of cliff-hangers before commercial breaks and at the end of each episode. Combined with other typical ingredients from action series, such as ambiguous romantic affiliations and a simplistic characterization of villains, these elements are important in defining 24.

<13> 24 is considered a success in terms of audience ratings ‒ the premiere of Season 6, for instance, attracted 15.7 million viewers in the US alone (Mahan 2007). The show is also broadcast widely in other parts of the world, including the Middle East. Its success may be partly attributed to the creators of 24 having managed better than other US TV‒ serials to fulfil viewers’ post 9‒11 fear-based fantasy of a macho, tough and protective hero, Jack Bauer, a man who does not hesitate from going to extremes to protect the nation from terrorism. Bauer applies controversial methods, including some that are blatantly illegal, such as torturing suspects to get information and assassinating villains after they have been disarmed. The hero’s actions step over the boundaries between common conceptions of right and wrong, and this underlines the very essence of the TV‒series action genre. In this TV genre violence constitutes a fundamental conflict between the masculine as an ideal and the social as a precondition, where violence and masculinity go hand in hand.

<14> The action genre in TV serial drama is defined by the action hero — a single white man – finding his utopian independence and freedom being constantly under threat from the community, society and the law (Schubart 1997: 68). The violence committed by macho heroes like Jack Bauer demonstrates an unwillingness to, and protest against, obeying the rules of society.[9] On several occasions this is to the detriment of innocent people. In Season 4, for example, he suspects his girlfriend’s ex-husband, Paul Raines, of cooperating with the Muslim terrorists. After forcing his way into Raines’ hotel room, Bauer beats him up and tortures him with an electrical cord from a lamp. These actions are much alike those of the terrorists he is supposed to be combating and demonstrate a shared willingness to attain the goal of stopping the enemy at all costs. This representation of the hero’s detachment from accepted rules and norms in society may be understood in the context of an older hero myth, namely, the American "frontier hero". A common feature in the Western genre, the myth centres on conquering the wilderness and the subjugation and "removal" of the indigenous population (Dyer 1997: 32-37). Redemption of the white hero s spirit is achieved through a scenario in which he is separated from civilized life. There is a temporary regression to a more primitive or "natural" state, with the hero then being regenerated through the use of violence. The enemies are believed to be "savages", who, by the combination of their blood and culture, are inherently incapable of progress or civilization. The savages commit heinous acts against civilized people, and their actions are so extreme that they defy the laws of nature. For civilized heroes there seems to be no other way than to confront them using their own methods (Slotkin 1973). The myth of the "frontier hero" corresponds to Bauer’s uncompromising fight against Muslim terrorists, and Bauer frequently stresses the importance of never negotiating with them. Controversial heroes who deploy "dirty" tactics (e.g. Dirty Harry) have long flourished in American popular culture. Bauer may thus be seen as a continuation of this tradition.

Major threats in Season 4

<15> In Season 4, Muslim terrorists from the Middle East, the US, and England are the main enemies cooperating with co-conspirators like Mitch Anderson (a white pilot who was dishonourably discharged from the US Air Force), an African-American spy at the CTU, and some nuclear physicists from China. A special type of terrorist is selected to constitute the initial threat and to carry out the first, spectacular and ‘shocking’ attack in each season. In Seasons 2, 4, 6 and 8 the threat emanates from terrorists linked to the Middle East. Season 4 differs from the others, as in this season there is not a more powerful non-Islamist force involved in the terror activities. While Seasons 1, 2 and 3 focus on an extensive and lasting threat to the US — for example the main threat in Season 3 is a virus attack — Season 4 has no one principal threat that last the entire season. This leads 24’s approach to storytelling in a new direction, where the narration here moves from one threat to another. As a consequence, the intense action scenes are accentuated at the expense of informative and plot‒elucidating dialogue.<16> Habib Marwan is the enemy mastermind in Season 4. He organizes a large network of terrorists, who are mainly recruited from the Middle East, but live in the US as so‒ called sleeper cells. A series of attacks on the US is carried out by these terror cells. Marwan features in sixteen episodes, and in the course of these he personifies a malicious form of anti-American terror. Otherwise, the faces of Muslim terrorists are seldom clearly shown on the screen. Instead, these secondary villains are typically depicted as a depersonalized mass. Marwan provides to the viewers a junction between the terror cells and the various acts of terror. The acts of terror often function as cover operations for new and seemingly "even more dangerous" terror attacks, increasing the impression of chaos. Executive producer of 24, Howard Gordon feels that the season came to lack continuity, shifting as it did from one threat to the next:

[This season] had everything but the kitchen sink. If you actually describe what happened, it’s insane! Let ’ s break down the Internet to facilitate melting down the nuclear power plants, which really was a slight of hand for the stealth bomber and a series of attacks with increasing improbability (DiLullo 2007: 18).

The barbaric Muslim

<17> Stereotypes clip into codes and conventions associated with inclusion and exclusion. Viewers may not be like the hero, but they are certainly not like ‘the others’ (Hayward 2006: 385). A case in point is the Araz family in Season 4 of 24.[10] Navi Araz, the father, displays character traits that viewers probably neither can nor wish to be associated with. His role is that of the patriarchal despot. When his wife Dina and son Behrooz disobey or work against him and his plans, he punishes them brutally and harshly. He displays a willingness to sacrifice everything in order to carry out terror plans against the United States and is portrayed in line with the cliché of the fanatical, dedicated Muslim terrorist who will be rewarded in heaven for fighting the ‘infidels’. Navi is depicted as an enemy who seems to act in accordance with jihad, a concept stemming from Arabic that means "to strive or to exert oneself [in] a ‘determined effort’, directed at an aim that is in accordance with God’s command and for the sake of Islam and the Muslim ‘umma’ (Moghadam 2007: 347). In Western mass media, Muslim terrorists are typically associated with jihad, and are not perceived to act according to the logic or the moral code that applies in "the civilized world". Accordingly, they are viewed as deviant, barbaric people. This view has its roots in the fact that ‘jihad’ connotes a worldwide war against progress and evolution in the West’s dominant discourses (Karim 1997: 170).[11]

<18> In episode 4, Navi pats his son’s head in recognition of his efforts in dealing with the girlfriend issue. In the next episode, he orders his son to be killed. These acts deviate from the logic and moral code according to which villains in Hollywood fiction usually operate. Navi’s order is also the fatal turning point in the storyline about the family. When he returns home after Debbie’s death, he believes that Behrooz shot her. Navi acknowledges that it must have been difficult for Behrooz, yet necessary. In the following episode, Navi deceives his wife, claiming that it is their leader, Marwan, who wants Behrooz eliminated. She cries and accuses him of letting their son be murdered. To this Navi replies that Behrooz ceased to be their son a long time ago. Living in the US has changed him and made him a stranger. In these scenes, the father ’ s primitive nature emerges in the degree of brutality he exerts towards his own child. It is difficult to understand Navi’s order to a terrorist-collaborator to assassinate his son. The punishment appears unreasonable, illogical and extremely brutal.

|

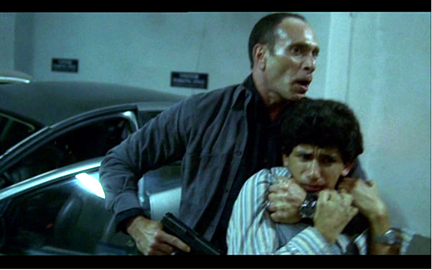

| Illustration 1: Navi takes his son as hostage and uses him for cover when Jack Bauer attempts to arrest him. Navi warns Bauer, who is holding him at gunpoint: ‘Careful, you may hit the boy’ . |

<18> The sequence where Navi uses his son as hostage (see illustration 1) reveals primitive survival mechanisms in his personality. He leads his son to a car in a parking garage, but on their way out they meet Bauer, whom Navi attempts to run over. Lying on the ground, Bauer manages to shoot out the back wheel of the car. Navi then has to find another way to escape, and his solution is to take his son as hostage and to use him as a human shield. When Bauer tries to arrest him, Navi points a gun to his son s head. Bauer relents, making their escape possible. In this scene it becomes clear that not only does Navi have a barbaric nature — he is also aware of his own unscrupulousness and uses it to his advantage in relation to people he presumes to be ethics-bound. Furthermore, one may speculate whether the background for his assumption that a white American agent is less unscrupulous than he, is an assessment he makes based on intuitive cultural knowledge. If this is the case, Navi confirms by these actions both his own and his cultural milieu ’ s tendency to use every means to reach their goal. Navi is depicted in a manner which corresponds to the West’ s dominant discourses on Islamic terrorism. In these discourses the violence exercised by Muslims is considered as the worst form of terrorism. The violence is taken to be the protest of barbaric irrationality against modern civilization and to be supported by a historical tradition of fanatical violence (Karim 1997: 166).

The insidious Muslim

<19> The narrative cliché of a mother torn between her disobedient son and his despotic father, describes Dina. Ultimately, she has to choose sides. She is represented as a mother caring for her child, but this is offset by her loyalty to her husband and ‘the cause’ . A number of times she tells Behrooz that he needs to obey his father. When Behrooz secretly maintains contact with Debbie, Dina helps her son conceal this, to avoid his being punished by his father. Dina is involved in the acts of terror and is dedicated to the terrorists ’cause’ . She makes this clear in her interrogation by Bauer, telling him that she would take pleasure in causing a nuclear power station to melt down. |

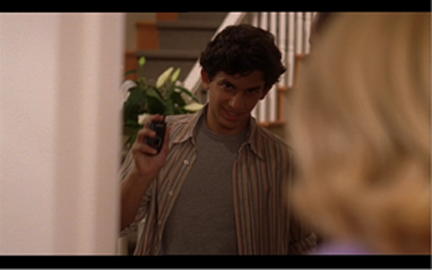

| Illustration 2. Dina after shooting Debbie’s corpse. |

Characterizations of Muslims and Arabs in Western TV—entertainment are often rendered through visual signs such as gestures, expressions, apparel, and surroundings. The accepted visual code for "TV Arabs" fits neither Dina nor her family who, for example, wear Western clothes. Richard Dyer (1997: 63) perceives a tendency in Hollywood films for whites to be associated with the good guys, and blacks with the bad guys. Merging transitions exist between the categories of hue, skin and symbol, with white often equated with good and black with evil. A white person who is bad is failing to be ‘white’ , whereas a black person who is good comes as a surprise, and one who is bad merely fulfils expectations. Skin colour plays an important factor in the portrayals of peoples and race in 24. The Araz family can be recognized as Muslims originating from the Middle East through visual cues like their light brown skin and dark eyes and hair. One auditory cue is the parents’ characteristic accent. However, it should be pointed out that the Araz family’s appearance and lifestyle may be regarded as how the family disguises their double roles as Muslim terrorists. Shaheen (2001: 2) asks rhetorically when was the last time that one saw a movie depicting an Arab or an American of Arab heritage as a regular person? Even though Dina is not an easily recognizable Muslim Arab stereotype in appearance, she becomes a stereotype through her bizarre actions. It does not seem reasonable, even for mothers portrayed as villains in US televisual entertainment, to keep their sons present, albeit unknowing while murdering their girlfriends.

<20> In the segment where Debbie is killed, Dina is presented as combining the role of mother with that of a Muslim terrorist. Dina hands her son a gun and asks him to get it over with. Instead, Behrooz and Debbie attempt to escape, but on their way out Debbie collapses and dies. Afterwards, she expresses her great disappointment in him. Dina then shoots the girl s corpse (see illustration 2) to make it look like Behrooz has killed her, so that her husband will be pleased. In these scenes, Dina fills the traditional role of the mother as a negotiator and stabilizer in the family. At the same time she is portrayed as a stereotype, and displays traits which can be linked to several primary stereotypes of Muslims. But the stereotypical trait that is most prominent does not correspond with these: it is the stereotype of "the insidious Muslim". This is in line with how Muslims often are portrayed on American television; insidious Muslims as violent strangers intent on combating non-believers everywhere (Shaheen 2000: 23). This stereotype may be regarded in association with how Muslims are viewed in the dominant discourses of the West; as endemically treacherous (Karim 1997: 177). Dina displays a striking level of mendacity, cunning and manipulation in the way she hides and reveals things to her own family and others. She plays on her son’s expectations of her as a mother, Debbie ’ s of her as her boyfriend ’ s mother, and Navi’s of her as an Islamic warrior and obedient wife. Dina does not live up to any of these expectations, but instead plays on them in order to betray.

The violent Muslim

<21> The character, Behrooz, is the most ambiguous in terms of stereotypes. In many ways, Behrooz is like most teenagers in his style of clothes and activities. He is at odds with his family, with his father, the adversary, and his mother, the go-between. Nevertheless, his relations with his parents and international terrorism show a side that hardly corresponds with what most people would consider a stable and wholesome upbringing. As a fictional character, he cannot therefore be placed in the category of a "social type", which applies to people who live according to the rules of society. He is a young man torn between two cultures and his family’s participation in terrorist activities against the USA. But even when his girlfriend is sacrificed for the cause, Behrooz does not distance himself from his family, who have got him involved in terrorism. In the opening scene, his father accuses him of not having broken off his relationship with his girlfriend, Debbie. Behrooz says he has ended it, but his father replies that he listens to his son ’ s phone calls and reads his e-mail, and therefore knows he is lying. Behrooz finds this unreasonable, but after being reprimanded he replies "yes, sir". In this scene, Behrooz appears to be the obstinate teenager who does not wish to obey his parents. His reply seems to indicate he obeys them only because of his father’ s authority. During that same day, Behrooz works against and defies his parents on several occasions, thereby resembling the stereotype of the rebellious teenager disobeying his parents.<22> There is a pattern in regards to when Behrooz chooses to oppose them and when he does not. For example, he does this whenever his family is discussing his girlfriend, appearing in certain scenes as a typical teenager who acts rashly and on impulse for the girl he longs for. This side of him emerges in the scene when he hands over a suitcase to terrorists and discovers that Debbie has followed him. Instead of doing something drastic to remove her from this dangerous place, he instead in a long conversation spends time trying to sort things out between them, displaying audacity which jeopardizes both his girlfriend’s life and the terror plans. However, he does not oppose his parents ’ terror plans and actions when the family is watching a news report about an act of sabotage that resulted in a train crash. Navi comments the news by proclaiming that what they will achieve today will change the world, and they should all feel honoured to have been chosen for this mission. To this Behrooz replies "Yes, father". He responds thus several times when the conversation touches upon terrorism, and not by "Yes, sir", which he answers in situations where he displays a negative attitude.

<23> Behrooz has characteristics which are associated with several primary stereotypes. When Behrooz is sent with a fellow terrorist to dispose of Debbie’s body, he demonstrates innate violent traits. As they are digging a grave, he observes that the terrorist is concealing a gun. Because of this, Behrooz hits him repeatedly in the back of the head with a shovel until he dies. Later in the storyline, Behrooz assassinates his father by shooting him from behind. In these scenes, Behrooz appears to be someone inclined to kill his own in ways which are hardly honourable, even though the violence has been provoked. The grave-digging colleague seems to have been put out of action on the first strike of the shovel and no longer poses any threat. The CTU has already captured his father, meaning that Behrooz’ act seems to be motivated strictly by vengeance. The way in which Behrooz is portrayed supports the image of Muslims as innately prone to use violence (Karim 1997: 166).

|

| Illustration 3. Debbie’s mother is at the door to the Araz. Behrooz covers up the murder by claiming to have the same ring tone as Debbie. |

The stereotype of the rebellious teenager does not merge with the stereotype of the violent Muslim. Indeed, the Behrooz figure may be too multilayered to constitute a stereotype character, especially since he undergoes a change from obeying his father to rebel against him. The conflict between father and son reaches a climax, and ends with Behrooz committing patricide. In the season, the son is depicted as split between two stereotypes.[12]

<24> Still, one stereotype features more prominently than the other, and the scene in which Behrooz helps cover up the murder of his girlfriend is illustrative. When Debbie’s mother visits their house in search of her daughter (see illustration 3), he helps his parents out of a difficult situation. Debbie s mother worries when she hears the sound of her daughter’s mobile phone, but Behrooz covers up the murder by claiming to have the same ringtone on his mobile phone. In this crucial situation, Behrooz chooses to protect his parents. His representation thus seems to be most in line with the stereotyped image of a violent Muslim.

Conclusion

<25> The makers of 24 set themselves the goal of basing the Muslim characters in reality, and with the Araz family they believe they have succeeded. However, this analysis of the family ’ s portrayal suggests otherwise. It shows that the portrayal is largely stereotypical; the family can be said to consist of stereotyped Muslims that fit into various categories of well- documented stereotyped images of Muslims in Western popular culture. This analysis of the storyline demonstrates that the makers of 24 hardly present a balanced portrayal. Instead, the representation draws extensively on the discourse of Orientalism. A key point in Orientalism is that the Orient is constructed through Western representations. Edward W. Said regards Orientalism as a multi-faceted discourse characterized by ideas which he describes as Orientalism’s most important dogmas, for example the tenet that there is an absolute and systematic difference between the Orient (irrational, undeveloped, inferior) and the West (rational, developed, superior) (Said 1995: 300-301). The systematic differences between the portrayal of Bauer, the CTU and the Araz family are in line with this discourse. On the one hand, Bauer and the CTU represent Western values and are portrayed as rational, "developed" and superior. On the other hand, the Araz family is portrayed as irrational, "primitive" and inferior. Still, the family ’ s unpredictable and violent actions spread fear and cause trouble, both for their surroundings and for themselves. Their actions seem to stem from inherently destructive and barbaric impulses, as they cannot be understood either through the characters ’ moral persuasions or other manifest motives.

<25> In the family, the son, Behrooz, is portrayed less stereotypically than the others. He is more complex; he undergoes a change during the day when he rebels against his father and can thus be regarded as a stereotypical rebellious teenager. Nevertheless, this analysis indicates that his portrayal corresponds more with the stereotype image of Muslims possessing an innate violent tendency. The mother in the family, Dina, is portrayed stereotypically because she is represented as a treacherous woman who manipulates and betrays people, even those with whose she is allied. The father, Navi, is the most obvious stereotype in the family. Shaheen (2001: 2) describes as follows one of the most widespread images of a stereotype Muslim Arab in Hollywood films: "Pause and visualize the reel Arab. What do you see? […] perhaps he is brandishing an automatic weapon, crazy hate in his eyes and Allah on his lips. Can you see him?" Navi represents the prototypical "reel Arab". He performs extreme and violent acts against both the civilian population of the US and his own family. The violence he commits can be interpreted and understood as opposition to modern civilization, which in 24’s diegetic world constitutes a contrast to the irrational, primitive and brutal character traits he displays.

<26> Modern Orientalists’ observations and descriptions of Arabs´ character traits include the notion that they lack discipline and the ability to cooperate:

The Arabs so far have demonstrated an incapacity for disciplined and abiding unity. They experience collective outbursts of enthusiasm but do not pursue patiently collective endeavors, which are usually embraced half-heartedly. They show lack of coordination and harmony in organization and function, nor have they revealed an ability for cooperation. Any collective action for common benefit is alien to them (Hamady 1960, cited in Said 1995:309-310).

These observations are recognizable in the Araz family. They are consistently represented as incompetent; they are unable to cooperate, whether to promote the terror cause or for the common good of the family. Instead, they consistently manipulate and deceive one another. Their collective efforts to perform acts of terror against the USA result in conspiracies, suicide attempts and attempted murders and assassinations of close family members and fellow terrorists. This representation of stereotyped Muslims becomes paradoxical in several ways. The family members are at once mystical, primitive and ignorant; still, they show great skill in their capability to manipulate and lie in a masterly manner. In Season 4, no explanation is offered for the family’s political or social motives for committing terror acts. This bears similarities to the way in which the Western news media tend to portray terrorism; the focus is typically on the act of terror and the government’s reaction, not on the background for or contextual aspects of terrorism (Picard 1993: 85-88).

<27> In relation to the different stereotypes of Muslims and Arabs in Hollywood revealed by media research, the Araz family carries on several such stereotypes through the acts they commit. Visually, however, they are different. There are few visual cues that correspond to the traditional stereotypes, but within, in character they remain true to type. In the past, plots usually took place in Hollywood’s "Middle East"; now they take place on US soil. This analysis indicates that the Muslim stereotype in US television entertainment post-9/11 has undergone a change related to the stereotype’s relocalization. The major Muslim stereotype today seems clothed in the appearance of the average American, which redefines the Muslim "other". The strangers are now hiding amongst us and may even be living next door.

<28> The new Muslim stereotype offers a bifurcated image of Muslims for day-to-day understanding. If steadily repeated by mass mediation, the stereotype is disturbing news for Muslim minority groups in Western societies and can have a deleterious effect on the development in multicultural societies. Hollywood’s delineation of Muslim characters is both a product of, and a producer of, the Wests dominant discourses on Muslims. Hence, an important question is how the US entertainment industry endeavours to anticipate, adjust and position itself to changes in the political climate and in dominant perceptions of Muslims.[13]

Endnotes

[1] In 2008, Queen Rania criticized 24 in a video clip on YouTube saying she is surprised by some of the questions she has been asked about the Arab world and the Middle East; do all Arabs hate Americans? Can Arab women work? If what most people know about the Arab world and its people come from TV-series like 24 and characters like Jack Bauer, they are in for a surprise. In addition, the Turkish embassy has expressed a negative view on 24 because of the show’s depiction of Muslims. The embassy in the US contacted the producers of 24 regarding Season 4, according to co-creator and executive producer of 24, Joel Surnow. This was because there were scenes with dialogue in that season which indicates the country where terrorist suspects came from (Bennett 2008).

[2] The 2009-2010 science fiction TV serial from ABC, Flashforward, is also named for its storytelling technique. The difference between Flashforward and 24, however, is that Flashforward’s storytelling technique also refers to and has a major function in the series diegetic world.

[3] 24 ’ s format is based on real time. In this way the viewer can get a sense of being able to follow characters in the storyline minute by minute. This is a time frame which restricts the program makers’ opportunity for character development, as people usually don’t change much during the course of one day.

[4] Chamberlain & Ruston (2007: 23) suggest that 24, with its demonstrative emphasis on style, and its convoluted and irresolute narrative, could be accused of elevating style over substance, sacrificing character development.

[5] Christian Blauvelt (2008) claims that the plot in 24 about the Muslim family works like Nazi propaganda fiction films did, like Jud Suss (1940) and Der Ewige Jude (1940) which instilled fear that people’s Jewish neighbours might be working to establish a foothold in Germany for the Soviet Union.

[6] Executive producer Howard Gordon states that he became aware of the problem that "fear sells" when Season 4 was being promoted. Fox’s marketing department placed a giant billboard over a motorway in Los Angeles. An image of the Araz family was accompanied by the slogan "They could be next door". Gordon agrees with CAIR’s assessment that "we were acting as handmaids to fear" (Gumbel 2008).

[7] In response to the criticism of Season 4, co-creator and producer Joel Surnow points out that: "For it to have any believability and resonance, we had to deal with the world we’re living with, with the terrorists and jihadists" (Ackerman 2005).

[8] In this article the stereotype is delimited to be understood as a way of representing people, although the conception in itself, especially as an adjective, is also used to refer to ideas, behaviour and ‘settings’ (see Dyer 2002: 17).

[9] In Season 7, which is set in Washington DC, Jack Bauer has to testify before a Congressional committee. He is asked to explain the extreme tactics and methods he has applied when trying to prevent terror attacks from occurring.

[10]A plot summary: The Araz family — husband (Navi), wife (Dina) and their seventeen-year-old son (Behrooz) — is one of Marwan’s sleeper cells. This Muslim family resides in an exclusive apartment in Los Angeles, where Navi runs an electronics store. They have lived in the US for five years, seemingly living the American dream. They facilitate the acts of other terrorists mainly by delivering weapon parts and information to them. The family stands out from the rest of this seasons Islamic terrorists, as they play a key role in Marwan’s master plan to cause numerous nuclear power stations in the USA to melt down. They are introduced when having breakfast in their (US) middle class home, as a newscast reports on a terrorist attack they were involved in. As well as discussing the attack with his family, Navi reveals that he is aware of his son’s ongoing relationship with a white American girl, Debbie, despite his disapproval of it. During the storyline Dina kills Debbie and Navi tries to have his son killed by a fellow terrorist whom Behrooz himself kills. Navi also murders his brother-in-law and finally Behrooz commits patricide. All of this happens as the family members in turn betray each other, and eventually Navi ends up dead and the others are captured by the hero in the series, Jack Bauer.

[11] Karim employs the geographical divide "north/south" instead of "west/east". Here the terms "west/east" are applied instead, as these are the terms generally used in relation to the notion of Orientalism.

[12] This supports the late Tessa Perkins’ assertion about stereotypes: "It seems that differentiation of stereotypes is often accommodated by alternative stereotypes rather than by an expansion of the stereotype" (Perkins 1979: 140).

[13] Further research is needed to conceptualise the full development and extent of the new Muslim stereotype’ s proliferation in Hollywood and network television drama.

Work Cited

Ackerman, S. (2005),"How real is ‘24’ ;?", Salon.com,16 May. http://dir.salon.com/story/ent/feature/2005/05/16/24/index.html Accessed 11 November 2008.

Anon (2005), "Action Alert: Watch ‘24 ’Tonight on Fox", CAIR Chicago, 10 January. http://chicago.cair.com/actionalerts.php?file=aa_watchfox01102005 Accessed 10 November 2008.

Bakshi, A. (2007), "How the World Sees Jack Bauer", Washington Post, 30 August. http://newsweek.washingtonpost.com/postglobal/america/2007/08/ jack_bauer.html Accessed 16 September 2008.

Bennett, T. (2008), 24: The Official Companion: Season 6,London: Titan Books.

Blauvelt, C. (2008), "‘Aladdin, Al-Qaeda, and Arabs in U.S. film and TV": A review of Jack G. Shaheen (2001) Reel Bad Arabs. How Hollywood Vilifies a People", Jump Cut, 50.1.

Chamberlain, D. and Ruston, S. (2007), "24 and Twenty-First Century Quality Television", in S. Peacock(ed.), Reading 24: TV against the clock, London & New York: I.B. Tauris, pp. 13–24.

DiLullo, T. (2007), 24: The Official Companion: Seasons 3 & 4, London: Titan Books.

Dyer, R. (1977), "Stereotyping", in R. Dyer (ed.), Gays and Film, London: British Film Institute, pp. 27–39.

Dyer, R. (1997), White, London & New York: Routledge.

Dyer, R. (2002), "The role of stereotypes", in R. Dyer (ed.), The Matter of Images: Essays on Representation, London & New York: Routledge, pp. 11–18. First published 1993.

Eisele, J. C. (2002), "The Wild East: Deconstructing the Language of Genre in the Hollywood Eastern", Cinema Journal, 41.4, pp. 68–94.

Fuller, L. K. (1995), "Hollywood Holding Us Hostage: Or, Why Are Terrorists in the Movies Middle Easterners?", in Y. R. Kamalipour(ed.), The U.S. Media and The Middle East: Image and Perception, Westport, Connecticut & London: Greenwood Press, pp. 187–97.

Gumbel, A. (2008), "Operation stereotype", The National Newspaper, 1 July. http://www.thenational.ae/article/20080701/ART/778591133 27.9.2008.TV.com> Accessed 6 June 2009.

Halse, R. (2012), "Negotiating boundaries between us and them: Ethnic Norwegians and Norwegian Muslims speak out about the ‘next door neighbour terrorist " in 24", Nordicom Review 33(1).

Hayward, S. (2006), Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts, Canada: Routledge. First published 1996.

Kanfer, S. (2007), "Four Stars for 24. TV’s hottest thriller returns, as politically incorrect as ever", City Journal, 23 July. http://www.city-journal.org/html/rev2007-01-23sk.html Accessed 17 September 2008.

Karim, K. H. (1997), "The Historical Resilience of Primary Stereotypes: Core Images of the Muslim Other", in S. H. Riggins (ed.), The Language and Politics of Exclusion: Others in Discourse, Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage Publications, pp. 153–82.

Karim, K. H. (2003), Islamic Peril: Media and Global Violence, Montreal/New York, London: Black Rose Books. First published 2000.

Lippmann, W. (1991) Public Opinion, New Brunswick/London: Transaction Publishers. First published 1922.

Mahan, C. (2007), "Ratings: Jack Bauer vs. Globes," TV.com, 16 January

http://www.tv.com/24/show/3866/story/8132.html?tag=story_list;title;6 Accessed 6 June 2009.

Mandel, D. (2001), "Muslims on the Silver Screen", Middle East Quarterly 8.2, pp. 19–31.

Michalak, L. (1988), "Cruel and Unusual: Negative Images of Arabs in American Popular Culture", ADC Issue Paper, 15, pp. 1–42. First published 1975.

Miller, T. (2001), "The Action Series (The Man from UNCLE/The Avengers)", in G. Creeber (ed.), The Television Genre Book, London: British Film Institute, pp. 17–19.

Moghadam, A. (2007), "The Shi’i perception of Jihad", in B. Rubin (ed.), Political Islam: Critical Concepts in Islamic Studies, London & New York: Routledge, pp. 346–55.

Parry, W. (2007), "‘24’ Under Fire From Muslim Groups", CBS News, 17 January. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/01/18/entertainment/main2371842.shtml Accessed 5 September 2008.

Peacock, S. (2007), "24: Status and Style", in S. Peacock (ed.), Reading 24: TV against the Clock, London & New York: I.B. Tauris, pp. 25–34.

Perkins, T. (1979), "Rethinking Stereotypes", in M. Barret (ed.), Ideology and Cultural Production, London: Croom Helm, pp. 135–59.

Picard, R. G. (1993), Media Portrayals of Terrorism: Functions and Meanings of News Coverage, Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press.

Pickering, M. (2001), Stereotyping: The Politics of Representation, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire & New York: Palgrave.

Said, E. W. (1995), Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient, London: Penguin.

Schubart, R. (1997), "Single White Male: tv-actionserien i 90 "erne", Kosmorama: Tidsskrift for filmkunst og filmkultur,219.2, pp. 56–69.

Semmerling, T. J. (2006), "Evil" Arabs in American Popular Film, Austin: University of Texas Press.

Shaheen, J. G. (1984), The TV Arab, Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

Shaheen, J. G. (2000), "Hollywoods Muslim Arabs", The Muslim World, 90.1–2, pp. 22–43.

Shaheen, J. G. (2001), Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People, Gloucestershire: Arris Books.

Shaheen, J. G. (2008), Guilty: Hollywood’ s Verdict on Arabs After 9/11, Northampton: Olive Branch Press.

Slotkin, R. (1973), Regeneration through violence: The mythology of the American frontier, 1600-1860, Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press.

Tidrick, K. (1989), Heart beguiling Araby. The English romance with Arabia, London: I.B. Taurus.

Woll, A. L. and Miller, R. M. (1987), Ethnic and racial images in American film and television: Historical essays and bibliography, New York: Garland.

Return to Top»