Reconstruction Vol. 14, No. 4

Return to Contents»

"Work itself is given a voice": Labor, Deskilling, and Archival Capability in the Poetry of Kenneth Goldsmith and Mark Nowak / Michael Leong

[T]he newspaper arrives at our door, it becomes part of the archive of human knowledge, then it wraps fish.

-Malcolm Gladwell

<1> The title of Mary Ann Caws' recent article "Poetry Can Be Any Damn Thing It Wants" blithely, but no less accurately, indicates the anarchic condition, both liberatory and destabilizing, of contemporary North American poetry production-particularly in the way it speaks to the recent and controversial trend of conceptual poetry, which eschews the fragmentation and lexical, semantic, and syntactic difficulty that is the heritage of the so-called L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E group in favor of a resolutely anti-literary poetics of plagiarism, appropriation, and the readymade [1]. Indeed, Caws' title highlights the sheer nominating power of the poet: the conceptualist's animating concept takes precedence over the text itself, which, nevertheless, is considered "a poem." Such a development has put both the definition of poetic skill and the criteria for aesthetic evaluation into a severe crisis. How are we to judge poetry now that major strands of contemporary poetry are disavowing-sometimes with a vengeance-the traditional skill set of lyric expressivity, figuration, and metrical ability? What constitutes poetic skill or ability in the twenty-first century? For now, I wish to assert that a new aesthetics of the twenty-first century must surely take into account two interlocking questions: what is the work of poetry within a socio-cultural arena and what kinds of work go into the making and presenting of poetry?

<2> In order to answer these questions, I will analyze and put into critical dialogue the long poems of two very different writers, one associated with conceptual poetry (and the championing of what he calls "uncreative writing") and one associated with, however reductively, investigative or documentary poetry (and the championing of labor rights): Kenneth Goldsmith and Mark Nowak. Goldsmith is best known for his massive transcription projects such as Traffic (2007), a word-for-word transcription of traffic reports over the course of a day, or the forbiddingly long book Day (2003), an 836-paged transcription-it must surely be one of the longest poems so far in the new century-of an entire issue of the New York Times (Goldsmith transcribed all available text in the paper from photo captions to advertisements). Day was, importantly, "written" against Truman Capote's famous quip about Jack Kerouac's On the Road: "That's not writing. That's typing" [2]. Nowak, on the other hand, is best known for documenting working-class experiences in books such as Revenants (2000), which explores Polish communities in Western New York, and Shut Up Shut Down (2007), which details the hardships and complexities of the labor movement along a deindustrialized rust belt. Both Revenants and Shut Up Shut Down are collections of long, serial poems that, while immensely shorter than Goldsmith's conceptual projects, nevertheless present length as an indicator of sustained socio-cultural ambition. In reviewing (favorably) Nowak's most recent book Coal Mountain Elementary (2009), a collocation of found texts about the global coal mining industry, Maurice Manning begins by acknowledging the extreme uncertainties regarding evaluation, genre, and authorship I mentioned above: "To call Mark Nowak's haunting new book a collection of poetry would be a bit of a misnomer. It would also be misleading to say Nowak is its author." This would seem to put Nowak firmly into Goldsmithian territory; the trajectory from Revenants to Coal Mountain Elementary certainly suggests a clear turn away from the recognizably poetic toward an aesthetic of extended citation or copying. Nevertheless, on the level of theme or content, the difference between the two writers seems glaring. On the surface, it looks like we have, on the one hand, a poet who radically re-conceptualizes the labor that a poet can and ought to do through a fastidious engagement with ambient, everyday textualities (newspapers, traffic reports, etc.), and, on the other, a poet who explicitly thematizes labor and worker's rights as fundamental and pressing concerns. In short, it appears that we have two poets interested in labor but one whose interest is primarily technical (as it relates to poetry's method) and one whose interest is primarily thematic or content-based. But such an understanding, while tempting, would be naively incomplete.

The Practice of Archiving

<3> Throughout the course of this essay, I adumbrate the similarities between Goldsmith's Day and Nowak's photo-documentary poem "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down," the final series from Shut Up Shut Down, which records job loss and economic hardship in towns throughout the iron range due to the bankruptcy of LTV Steel (the third largest U.S. steel maker) and the closing of its taconite mine and processing facilities. I show how the two very different poems, when considered together, offer a nuanced understanding of the work of poetry and the work in poetry within a global economy without unnecessarily privileging technique over theme or content over method. I also demonstrate how Day, in fact, thematizes labor, and how "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down" entails a redefinition of the poet's job along with a redefinition of what should constitute the materials of poetry. Moreover, this unlikely pairing will show that conceptual poetry and documentary poetry converge at a point which I will call the archive. Though it is true that both Day and "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down" draw on newspaper archives for source material-Day perversely and spectacularly reproduces one single newspaper in toto while "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down" draws on over twenty articles from local Minnesota publications-Goldsmith's and Nowak's works don't employ unique or original documents in the way Susan Howe uses, say, a picture of a piece of fabric from the Beinecke's Jonathan Edwards Collection in Souls of the Labadie Tract (2007) or a facsimile image from Charles Sanders Pierce's manuscripts in The Midnight (2003). Thus, by "archive," I don't mean "the sum of all the texts that a culture has kept upon its person as documents attesting to its own past" (145)-such a definition, which Foucault explicitly rejects in The Archaeology of Knowledge, clearly informs Malcolm Gladwell's loose, metaphorical understanding of "the archive of human knowledge" ("Something Borrowed.") Nor do I mean "institutions, which, in a given society, make it possible to record and preserve those discourses that one wishes to remember and keep in circulation"-Yale's Beinecke Library, one of Howe's favorite research sites, is part of such an institution (Foucault 145). Following Foucault, I understand the "archive" as a set of practices. Foucault's archive, situated "between the language (langue) that defines the system of constructing possible sentences, and the corpus that passively collects the words that are spoken[,]…reveals the rules of a practice that enables statements both to survive and to undergo regular modification" (146).

<4> It is my argument that poetry, as a discursive formation (that is, as a group of statements), has been in the midst of an irregular modification, and the epistemic shift in the way we are now re-conceptualizing the discipline "creative writing" has been provoking the crisis in evaluation to which I alluded above. This is why Manning is so hesitant to consider Nowak's Coal Mountain Elementary "poetry" even though the book's subtitle, according to the Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data, is "New and Selected Poems." Yet I wish to take Foucault's idea of the archive as "a practice of modification" and place it in the interval between the corpus (and its potential uses) and language as parole instead of language as langue, orienting it away from an impersonal discursivity toward the subject's performative appropriation of pre-existing materials. The practice of re-working and re-situating extant language is part of what I will be calling "archival capability" [3]. I don't wish to detract from the value or scope of Foucault's archaeological method but rather to highlight the active role that poets play in modifying what he calls "the law of what can be said" and the way poets re-imagine crucial activities, such as reading and writing, which allow us to process, produce, and transform our knowledges [4].

<5> My focus, then, will not be on "The Archive" as some reified entity but on archiving as a dynamic set of personal, social, and cultural practices. I also wish to analyze within these writers something akin to what art historian Hal Foster calls "an archival impulse." In his suggestive article "An Archival Impulse," Foster identifies Thomas Hirschhorn (and his makeshift assemblages), Sam Durant (and his détournements of late modernist and postmodernist styles), and Tacita Dean (and her strange documentary photographs and films) as representative archival artists and argues that "[i]n the first instance" they "seek to make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present" retrieving "obscure" sources "in a gesture of alternative knowledge" (3-4). In this sense, an old newspaper is an eminently displaced and obscure source; as Gladwell casually remarks, "it becomes part of the archive of human knowledge, then it wraps fish." Goldsmith and Nowak wish, for varying reasons, to imbue such sources with renewed epistemological value. Such notions of displacement and obscurity-on a social level-are also crucial to Nowak's activist project: the title of his book, Shut Up Shut Down, suggests that the imperiled workers he advocates are being "shut up" by corporate and political interests as their livelihoods are being "shut down." It harbors an anxiety that his subjects have already been "archived" out of public consciousness-and here, we can understand the verb to archive as it is employed in computing: "to transfer to a store containing infrequently used files, or to a lower level in the hierarchy of memories" ("Archive, v."). Nowak's "archival impulse" involves a re-situating of neglected information from the lower hierarchies of social memory into a counter-archive of alternative knowledge.

<6> Goldsmith, on the other hand, is interested in computerized archiving in a more direct and specific way. Following digital theorist and film archivist Rick Prelinger, Goldsmith associates personal archiving on home computers as a kind of "folk art." For Goldsmith, the storing and configuring of digital files is like quilting-both involve the accumulation of various items into a heterogeneous mass. Yet, unlike quilting, the archival activity of personal computing might be subconscious: "The advent of digital culture has turned each one of us into an unwitting archivist. From the moment we used the 'save as' command when composing electronic documents, our archival impulses began." Goldsmith continues, describing the way he organizes and tags his music files:

Let's say I want to play a CD on my computer. The moment I insert it into my drive, a database is called up (Gracenote) and it begins peppering my disc with ID3 tags, useful when I decide to rip the disc to MP3s. The archiving process has begun. Unlike an LP, where all that was required was to slap the platter on a turntable and listen to the music, the MP3 process requires me to become a librarian. The ID3 tags make it possible for me to quickly locate my artifact within my MP3 archive. If Gracenote can't find it, I must insert those fields - artist, album, track, etc. - myself. ("Archiving is the New Folk Art")

Though Goldsmith stresses the automated and "unwitting" nature of these archival processes, he does, importantly, mention the deliberate act of inserting the ID3 fields of artist, album, and track himself [5]. Another important ID3 field is "genre," and we might, by analogy, even consider Goldsmith's most significant act in producing Day to be not the actual re-typing of the newspaper's content (he later used OCR technology to copy the text) but simply changing the New York Times' "genre tag" from "news" or "journalism" to "poetry." In other words, Goldsmith's most radical act is on the level of metadata rather than data. Metadata is, according to the National Information Standards Organization, "structured information that describes, explains, locates, or otherwise makes it easier to retrieve, use, or manage an information resource" and is similar to the cataloging work of an archivist or librarian (Understanding Metadata 1). Goldsmith, in fact, goes well beyond Ezra Pound's "memorial to archivists and librarians" in "Canto XCVI" (674) and collapses the very distinction between poet and archivist, writer and librarian:

Having moved from the traditional position of being solely generative entities to information managers with organizational capacities, writers are embodying tasks once thought to belong only to programmers, database minders, and librarians, thus eradicating the distinction between archivists, writers, producers and consumers. (Goldsmith "A Textual Ecosystem")

The task of the poet, according to Goldsmith, has shifted from a High Romantic imagining (à la Coleridge) to an administrative managing [6]. Although John Berryman's The Dream Songs anticipated, albeit in negative terms, Goldsmith's aesthetics of administration nearly half a century ago-in #354, Berryman sardonically says, "The only happy people in the world / are those who do not have to write long poems: muck, administration, toil"-digital tools have made manipulating and arranging information much less toilsome (286) [7]. Such tasks are part of a new poetic skill set-for Nowak, newer skills include "remix/sample/mash-up techniques" in the tradition of "Afrika Bambaataa and Negativland and (ex post facto) DJ Danger Mouse"-that constitutes archival capability (Nowak, "Notes toward an Anti-capitalist Poetics II" 334).

The Deskilling/Reskilling of Poetry

Is writing poetry a skill or can anyone do it?

-Mark Delahunte, question posed on "Yahoo!® Answers"

While traditional notions of writing are primarily focused on 'originality' and 'creativity,' the digital environment fosters new skill sets that include 'manipulation' and 'management' of the heaps of already existent and ever-increasing language.

-Kenneth Goldsmith, "Revenge of the Text"

<7> "The building blocks of poetry itself are elements of fiction-fable, 'image,' metaphor-all the material of the nonliteral" (Hollander 1). So goes John Hollander's popular primer Rhyme's Reason. Yet, in twenty first century poetry-particularly in long poems-we are seeing a new literality, a deliberate disavowal of poetry's fictive foundations along with a rejection of verse's rhythms and sonorous musicalities. For example, here are brief excerpts from Goldsmith's Day and Nowak's "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down" respectively:

Union officials said that they were not trying to pressure Bridgestone at a time of trouble. Rather, they said, workers at the nine plants, who have been working under temporary extensions since their contracts expired, have grown frustrated about not having reached a new agreement after months of talks.

"It seems that it's high time," Mr. Ramnick said. "Negotiations have been going on a long time, and the company has been stalling for a long time in the talks." (Day 225)

"In December, after LTV stopped making steel, a U.S. bankruptcy judge approved a plan that allows the corporation to stop paying health-insurance premiums and supplemental unemployment pay at the end of February for laid-off workers, and in June for retirees." (Shut Up Shut Down 155)

Both of these excerpts are based on news reports and contain a prosaic flatness far beyond the "informational style" of the realist novels that André Breton famously criticized in his first surrealist manifesto (7). (The Goldsmith excerpt comes from an article called "As Tires are Recalled, Bridgestone Faces Strike," and the Nowak excerpt is based on the article "Ex-LTV Workers Feeling Financial Pinch" from Minnesota's Star Tribune.) "Where is the art in this poetry?" one might ask. "Where is the craft? Where is the creation of fable, image, or metaphor?" But these would be the wrong questions to ask. Rather than seeing these texts as merely examples of a "deskilled" poetry, we need to acknowledge their archival capability-that is, we must also understand a concomitant "reskilling" operating within their processes of composition. After all, if Goldsmith insists that poets are assuming the tasks of archivists, data managers, and librarians, and if Nowak is taking technical inspiration from musicians and DJs as much as from other writers, we need to attend to the wider social and cultural forces and conditions that are shaping a new and expanded sense of literacy.

<8> The word "deskill" in English can be traced to the 1940s and refers "to the increasing [use] of unskilled labour" in factories ("Deskill, v."). The term was crucial in Marxist labor theorist Harry Braverman's account of the increased routinization and alienation of work under a Taylorist system of management. According to Braverman, the reliance upon new technologies rather than craft-based skill transformed workers into untrained and replaceable components divested of autonomy and creativity. In the context of the arts, the term was first used by Australian conceptual artist Ian Burn and was subsequently mobilized by art historian Benjamin Buchloh who defined "deskilling" as the "persistent effort to eliminate artisanal competence and other forms of manual virtuosity from the horizon of both artistic production and aesthetic evaluation" (Foster, Krauss et al, Art Since 1900 531). In terms of poetry, "artisanal competence" and "manual virtuosity" directly correlate to the crafting of rhetorical figures (Wallace Stevens' "the intricate evasions of as," for example) and the skills of formal versification (as in Shelley's brilliant use of terza rima in "Ode to the West Wind")-these are traditional abilities that Goldsmith and Nowak, by and large, repudiate. Deskilling, according to one reading, creates an affiliation or solidarity between the poet/artist and the non-artistic worker (who is subjected to the socially divisive effects of capitalism) and democratizes a seemingly elitist and isolated artistic process.

<9> In The Intangibilities of Form, art critic John Roberts has usefully situated deskilling within a larger "dialectic of skill-deskilling-reskilling" and conceives of artistic authorship as "an 'open ensemble of competences and skills'…grounded in the division of labour" (2-3). Such a dialectic, I argue, has vast implications in our understanding of recent developments in North American poetry and can help us come to terms with the radical uncertainty of an age when "poetry can be any damn thing it wants." According to Roberts, "[t]he nomination of found objects and prefabricated materials as 'ready-made' components of art is the crucial transformative event of early twentieth-century art" (21). He reads the Duchampian objet trouvé-such as Duchamp's famous urinal-as-fountain-as a site of both alienated and unalienated labor (being an industrial-made object presented as an artifact of artistic labor). Rather than seeing "Fountain" (1917) as just an example of deskilled art or sculpture-without-craft, Roberts stresses the role of Duchamp's immaterial labor in reskilling the role of the artist: Duchamp performs valuable intellectual work in "disclos[ing] the capacity of commodities to change their identity through the process of exchange" (34). In other words, just as a urinal becomes art without the artist's physical intervention (and this is the virtue of Duchamp's "unassisted" readymade), an object becomes a commodity precisely through a transformative process that, as Marx says, "transcends sensuousness." Thus, I read both Goldsmith's and Nowak's poems as reskilled works "in which productive labour [that is, labour which returns a profit or surplus-value to the employer] and artistic labour are conjoined in a state of critical tension and suspension" (41). Both works are, moreover, utterly dependent on the work of newspaper editors and journalists for their textual substrate and, in the words of Christopher Schmidt, "remind…us of the vast work expended in the newspaper's production" (26).

<10> The newspaper is not only an apt figure or synecdoche for Gladwell's "archive of human knowledge" but it also is an especially privileged textual site that can reveal the modern dynamic between consumer and producer as well as a new sense of literary competence. It is no wonder then that the newspaper figures so prominently in both Goldsmith's and Nowak's compositional techniques. In the now classic essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility," Walter Benjamin describes the utopian potential of the newspaper and identifies, within its circuit of production and consumption, a literary deskilling and reskilling avant la lettre:

With the growth and extension of the press…an increasing number of readers-in isolated cases, at first-turned into writers. It began with the space set aside for 'letters to the editor' in the daily press…[the ease of finding] an opportunity to publish somewhere or other an account of a work experience, a complaint, a report, or something of that kind. Thus, the distinction between author and public is about to lose its axiomatic character. The difference becomes functional…At any moment, the reader is ready to become a writer. As an expert-which he has had to become in any case in a highly specialized work process, even if only in some minor capacity-the reader gains access to authorship. Work itself is given a voice. And the ability to describe a job in words now forms part of the expertise needed to carry it out. Literary competence is no longer founded on specialized higher education but on polytechnic training, and thus is common property. (144)

While Benjamin's notion of the worker as "expert" ("even if only in some minor capacity") doesn't accurately describe the post-WWII deskilled laborer, his notion of "polytechnic training" holds immense promise for both productive and artistic workers. This insistence on a flexible non-specialization opens writing up to a range of social fields. Nowak mines local newspapers precisely because they have, to some extent, given work "a voice," and, as we will see later, he draws on extra-literary skills, such as photography, to embrace a populist aesthetic of amateurism. Goldsmith's erosion of the line between "producers and consumers" is clearly indebted to Benjamin's theorization of artistic production as it interfaces with technical reproduction. Moreover, Day playfully takes up Benjamin's observation that "[the newspaper] reader is ready to become a writer" by rewriting the very newspaper which allows for this expanded sense of writerly competence.

"A whole new skill set": The Work of Art in the Age of Optical Character Recognition Technology

It would indeed seem as if the postmodern credo-the creative impulse in the era of cybernetics-is a DOS command: 'copy*.*.'

-Sylvia Söderlind, "Margins and Metaphors: The Politics of Post-***"

<11> The fact that Goldsmith began Day on September 1, 2000, the Friday before Labor Day Weekend, immediately announces its preoccupation with labor, and I wish, accordingly, to analyze the labor both in and of Day on multiple levels. That Goldsmith's project merely involves a transcription/copying of a found text, without any authorial intervention, shows the self-conscious reskilling of poetry: we are meant to focus not on the creation of new material but on the critico-conceptual work that his appropriation project is meant to accomplish. In short, he is highlighting not his imaginative poiesis but his archival capability. Moreover, Day, as an archive of numerous stories, contains important accounts of work experiences (giving, as Benjamin said, work a "voice"). In fact, a fact sheet provided by The New York Times Company, reiterates Benjamin's point in strikingly similar language (and, through a polyptoton, simultaneously advertises the publication's cultural capital): "As a resource of the influential, The Times also gives voice to those without influence" ("Did You Know? Facts about The New York Times"). That Goldsmith chose the New York Times as his source text-a publication that "has approximately 1,150 news department staff, more than any other national newspaper"-makes us consider Day as a kind of massive collaborative project dependent on numerous hands, as a deliberate alignment of the labor of non-artistic and artistic workers.

<12> As mentioned above, Day began as a typing project, a retort to Capote's snide distinction between well-crafted literary writing and Kerouac's "empty" typing [8]. As such, Goldsmith's newspaper appropriation seems particularly legible as a body art project-a rejection of literary standards of quality in favor of a feat of physical endurance, of the body's sustained and perverse engagement with an inscription technology. The back cover copy of Day, in good advertising fashion, highlights the text's conceptual mechanism along with its toilsome execution; it refers to Goldsmith's "typing page upon page" of the New York Times, which includes such dry and exhausting material as stock quotes and baseball box scores. There is even a quote from Goldsmith himself that authenticates his chosen process: "…with every keystroke comes the temptation to fudge, cut-and-paste, and skew the mundane language. But to do so would be to foil the exercise." Some reviewers, moreover, find Goldsmith's "un-fudging" commitment to the labor of every keystroke to be the project's most redeeming and meaningful factor. Raphael Rubinstein, commiserating with the physical tediousness of the poem's procedure, says of Goldsmith:

he must have recognized his own situation when he copied the lead sentence of an article on Andre Agassi: 'There are days when an adult goes to work and just doesn't feel like being there.' But it's precisely by his devotion to this demanding project that Goldsmith brings new meaning to his material, something that never would have happened if he'd simply scanned the pages into his computer. (53)

As is often the case with texts that challenge normative protocols of interpretation, self-reflexive moments tend to come into high-relief and the suggestive Agassi quote is no exception. Day, Goldsmith tells us, was a "gig" that took him "a year" to execute, and surely there were times, suggests Rubinstein, when he had wished to absent himself from the task at hand ("Being Boring" 364). Yet Goldsmith later admitted that he, in fact, "foiled the exercise" by using Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology. Contrary to the framing paratexts of the book's epigraph ("That's not writing. That's typing.") and the back cover copy, Goldsmith chose to scan the newspaper's pages rather than type them letter by letter. On the surface, it seems like this shift in methodology has jeopardized what Rubinstein calls the "new meaning" of the entire project. It seems that Goldsmith, in a loss of devotion, failed to show up for work.

<13> Goldsmith, himself, attributes the move from typing to scanning to a different kind of "meaning": to a willed subversion of capitalist value. "[I]n capitalism," says Goldsmith, "labor equals value. So certainly my project must have value, for if my time is worth an hourly wage, then I might be paid handsomely for this work. But the truth is that I've subverted this equation by OCR'ing as much of the newspaper as I can" ("Uncreativity as Creative Practice"). Goldsmith here seems to be conflating how simple and complex labor is compensated, and there is nothing about saving time (or using time-saving technologies) that is inherently anti-capitalist. Moreover, Roberts reminds us, via Marx, that "labour and value are not identical." In fact, this very condition of labor-power's non-identicality allows for what Roberts calls "the negative power of human labor" and "a critique of the value-form": "A critique of the heteronomy of productive labor is…embedded in the labour process itself through labour's negative relation to itself-in the labourer's labour over and above value and, consequently, in the labourer's constant refusal or unwillingness to labour" (33) [9]. This is Bartleby's "I would prefer not to"-or Rubinstein's adult-who-doesn't-feel like-being-at-work actually refusing to work (or Andre Agassi putting down his tennis racket). In critiquing the unwillingness of Melville's Bartleby and Coetzee's Michael K, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri maintain, "This refusal certainly is the beginning of a liberatory politics, but it is only a beginning. The refusal in itself is empty" (204). Yet such "emptiness," I argue, can be filled with Goldsmith's transformation of heteronomous work through a reskilled and autonomous artistic practice, a practice which, in turn, critiques the heteronomy of productive labor.

<14> After all, Goldsmith still "went to work"; he just used a different set of skills (Benjamin's "polytechnic training") to accomplish the task. In short, he reskilled a practice of an already reskilled conceptualism (simply retyping an extant text already challenges and expands received standards and criteria of writerly competence). Moreover, by eventually rejecting the act of typing, Goldsmith diverts attention away from a heroicized and performative feat at the scene of writing (Day as meta-inscriptural body art) and brings into view the heterogeneity of the poet's tasks and an intentional reliance on mixed technologies. Goldsmith points out that "if there was…an ad for a car" in the September 1, 2000 New York Times, he would use "a magnifying glass" to read the car's license plate and transcribe it ("Being Boring" 364). From scanning pages to magnifying miniature license plate numbers, Goldsmith seems to revel in a whole range of activities besides writing. Thus, in reexamining Capote's writing/typing distinction, we find that typing, for Goldsmith, may have been too associated with writing and writing's physical choreography or with the modernist practice that preceded him. Goldsmith, after all, is invested in what he calls "a whole new skill set," a complete reskilling of literary activity:

Contemporary writing requires the expertise of a secretary crossed with the attitude of a pirate: replicating, organizing, mirroring, archiving, and reprinting, along with a more clandestine proclivity for bootlegging, plundering, hoarding, and file-sharing. We've needed to acquire a whole new skill set: we've become master typists, exacting cut-and-pasters, and OCR demons. (Uncreative Writing 22)

And, here, it is again tempting to indulge in another one of Day's self-reflexive moments. The job description that Goldsmith is detailing may be found, in part, in the very text he has replicated:

SECRETARY F/T Great Neck, L.I. CPA firm seeks responsible indiv. MS Word,

Excel: Exclnt salary & bnfts. FAX 516-466-3349

SECRETARY P/T or F/T For jewelry office. Computer and basic accounting

a must. Send resume to: PO Box 2544, New York, NY 10185

SECRETARY BILINGUAL, Diplomatic Mission seeks bilingual secretary,

French/English w/computer skills. Word 2000. Call 212-421-1580.

SECRETARY/BOOKKEEPER Computer literate, Word & Quickbooks. Fax

resume to: 212-366-0979. (829)

The job "secretary" is, of course, not the same as "faculty member with the Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing" and "Lecturer in the History of Art" at the University of Pennsylvania (where Goldsmith currently teaches) or "Anschutz Distinguished Fellow Professorship" at Princeton University (where Goldsmith taught in 2010). In other words, the affiliation Goldsmith has forged with productive office workers might be a relation of appropriation rather than solidarity; it might simply be "the mere imposition of non-heteronomous thinking." Yet, according to Roberts, this is not the case since "the hand at the machine in productive labour…will shape the content of the relations between autonomous and heteronomous labour" (97). Finally, what separates Goldsmith's task from the various secretary job descriptions listed above is the very autonomy of art-that Goldsmith, who is subsidized by prestigious universities, is able to work unconstrained without the controlling supervision of, say, the CPA firm or the Diplomatic Mission. He has the freedom and choice to "cross" the function of a secretary with that of a "pirate" and therefore to consolidate and practice his archival capability (Goldsmith's piracy is made abundantly clear at the very beginning of Day: "Copyright © 2000 The New York Times") (Day 11). In other words, Goldsmith is a digital-age scrivener with a difference [10].

<15> What Goldsmith produces is not a poetry that adheres to a Romantic or post-Romantic sensibility-a "spontaneous overflow of powerful emotions…recollected in tranquility" (Wordsworth) or "feeling confessing itself to itself in moments of solitude" (Mill) or "a momentary stay against confusion" (Frost) or "notes toward a supreme fiction" (Stevens)-but rather a new and provocative configuration of social relations of production. Through "a radical alignment of artistic labour with non-artistic labour," Goldsmith triangulates the work of a poet, the work of a journalist, and the work of a secretary/copyist (Roberts 149). Now that we've established the mixed work that it took to accomplish Day-work that started with the New York Times staff and ended with Goldsmith's reskilled archival capability-we are now in the position to evaluate the kind of intellectual work that Day, as a conceptual poem, accomplishes. To begin, we can consider Goldsmith to be "a theorist of artistic labour" (this is how Roberts reads Duchamp) vis-à-vis a bureaucratized, professional-managerial economy for all the reasons enumerated above (5). But there is more. Just as Duchamp's readymades expose "the apparitional identity of the commodity," Goldsmith's Day exposes the apparitional identity of the fetishized book object, making him a theorist of media and their cultural uses (Roberts 34). According to Marcus Boon,

It's certainly true that Day costs 20 times as much as the newspaper that Goldsmith has 'retyped'. But, as Walter Benjamin suggested, one does not necessarily buy a book in order to read it. The book as object confers a certain fetish value on the text it contains - a fetish value which Day exposes.

Indeed, on a bookshelf, Day-as a material object-would fit in quite inconspicuously among the epic tomes of modernism (such as James Joyce's Ulysses, Charles Olson's The Maximus Poems, or Louis Zukofsky's "A.") Day, in this sense, is a newspaper disguised as a literary monument.

<16> This work of "exposing" is akin to what Heidegger calls "revealing" (Entbergen). "Unlike poiesis," explains Sven Spieker, "which implies a direct shift from absence to presence, Entbergen uncovers and transforms what is already present yet invisible" (9). The numerous advertisements that Goldsmith reproduced are duplicated word by word but without pictures; thus, as Brad Ford observes, "the eye-catching tricks of Madison Avenue are stripped of all but caps and exclamations, and it deflates them or makes them comedy." In this way, Day uncovers the ideology of what Hardt and Negri call "[t]he new managerial imperative… 'Treat manufacturing as a service'" (285-6):

THE WORLD IS YOURS. THE MAINTENANCE IS OURS.

Welcome LAND ROVER

This is an invitation to venture forth with nary a care in the world. Because

now, for a limited time, you can lease a brand-new Land Rover, the most capable

4x4 on the planet, as we'll take care of all scheduled factory maintenance. Oil.

Labor. Et cetera. Just about the only thing with which you'll have to concern

yourself is exactly where to spend your 36-month honeymoon. COME SEE WHAT A LAND ROVER IS MADE OF. (771)

In this Land Rover ad, car manufacturing is treated precisely as a service-to the comedic extent that the leisurely consumer becomes "reskilled" as a wedding planner ("Just about the only thing with which you'll have to concern yourself is exactly where to spend your 36-month honeymoon.") The comedy is both humorous and generic: the ad is a micro-drama ending prosperously in marriage. Of course, the fact that production is tending toward the production of services creates an ideology that not only obscures the global economy's fundamental reliance on industry but masks the productive labor which makes services possible: Land Rover sublimates both oil and labor into a vague and abstract "et cetera." Moreover, the tension here between the tangibility of the vehicle ("WHAT A LAND ROVER IS MADE OF") and the intangibility of the services ("Labor. Et cetera") is a miniature recursion of Day's dialectical concerns: the materiality of the text and the intangibilities of its form.

"What is found there": Day's Content

Happy Labor Day weekend. Buy a steelworker a drink.

-Milton Glaser, quoted in Kenneth Goldsmith's Day

<17> In "Asphodel, That Greeny Flower," William Carlos Williams memorably says, "It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there" (318). What exactly can be found in Day that is tangible? Or to rephrase the question: how do we deal with the difficulty of confronting old news? Goldsmith seems to suggest that such a question is a red herring. In discussing Vanessa Place's conceptual work Statement of Facts (2010), a simple re-presentation of appellate briefs that Place wrote as a practicing lawyer, Goldsmith argues that "to linger on the content is to miss the concept: it's the matrix of apparatuses surrounding it…that give the work its real meaning" ( Uncreative Writing 104). And even more pithily: "context is the new content" (3). Yet such a dismissal, I argue, relies on the crude binary of content/concept and ignores the fundamental question of engaging the archive and what the archive records.

<18> Reviewer Bill Freind-in a reversal of the notorious Derridean idea that there is nothing outside the text-identifies Day as a content-less book, as a kind of vacuum between two covers: "Day is fascinating because it's so meaningless, so utterly empty of content that there is virtually no inside-the-text; it operates as a kind of conceptual vacuum which practically demands to be filled by the reader." Rhetorical cleverness aside, Day is, in fact, replete with content and meaning-not only content that, as I will show, perfectly coincides with Nowak's interests in working class rights but content from all across the social spectrum. (The text that Freind is describing more properly resembles Davis Schneiderman's recent conceptual novel Blank (2011), which is a 206-page "blank" book that contains only suggestive chapter titles and white-on-white pyrographic images by the artist Susan White.) Freind's understanding of Day is certainly conditioned by Goldsmith's very vociferous demotion of content and overly polemical insistence on the "valuelessness" of the material with which he works. In "Uncreativity and Creative Practice," Goldsmith says, in direct reference to Day, "Nothing has less value than yesterday's news." Similarly, in "I Love Speech," a paper originally delivered at the 2006 MLA Presidential Forum and published in Harriet, the Poetry Foundation's website, Goldsmith imagines the conflation of recording and archiving into one automated and non-interpretive act, doing away with all criteria for archivization (what archivists call "appraisal"):

I wish that they would graft an additional device onto the radio-one that would make it possible to record and archive for all time, everything that can be communicated by radio. Later generations would then have the chance of seeing with amazement how an entire population-by making it possible to say what they had to say to the whole world-simultaneously made it possible for the whole world to see that they had absolutely nothing to say.I wish that they would graft an additional device onto the radio-one that would make it possible to record and archive for all time, everything that can be communicated by radio. Later generations would then have the chance of seeing with amazement how an entire population…had absolutely nothing to say.

Goldsmith's desire to "archive…everything" is not in the service of preserving material that might have future historical value but because such an audio archive would demonstrate the ahistorical valuelessness of all broadcasted speech. "We're more interested," says Goldsmith, "in accumulation and preservation than we are in what is being collected" ("I Love Speech").

<19> This interest in collecting without selection, archiving without evaluation, is comparable to the poetics of Andy Warhol's Time Capsules, a serial project, begun in 1974, that consists of hundreds of cardboard boxes containing a morass of documents that Warhol encountered and collected during his everyday activities (documents such as magazines, newspapers, correspondence, and notebooks along with various ephemera like brochures and ticket stubs). According to Sven Spieker, "documents went into…[a Time Capsule] box not because they were important, valuable, or otherwise memorable, but because they were 'there,' on the desk" (3). Spieker likens such contents to "clutter and background noise," which suggests a link between Warhol's hoarding and the audio clutter of Goldsmith's notional radio archive of valuelessness. And what is the news in Day but news that was "there" to be reported on the "slow news day" of September 1, 2000 ("Being Boring" 364)? Yet Spieker continues and describes encountering what we might call an "irruption of content":

[Warhol's] boxes seemed to me like so much clutter and background noise-until, that is, I was suddenly struck by a small collection of Concorde memorabilia (napkins, tickets, dinner knives) that Warhol had brought back with him from one of his flights across the Atlantic. A few weeks before I visited the exhibit, a Concorde had crashed on an airfield near the French capital, killing all passengers aboard. Eerily, it was as if the presence of these articles in Warhol's archive only a week or so after the fatal crash commemorated an event, a trauma-that of those killed on the plane some three decades later-that had not yet occurred when the archive was put together. (3)

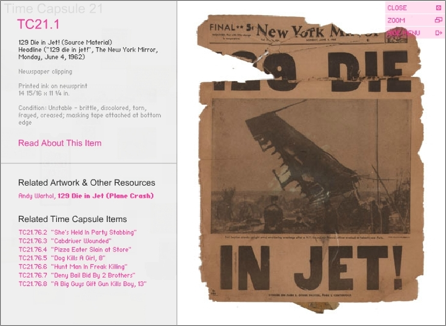

Even more, this eeriness is redoubled: Warhol's Time Capsule 21 contains-among business cards, invoices, manuscripts, and other assorted material-the front page of the New York Mirror, June 4, 1962, whose headline reads: "129 DIE IN JET!" This headline, of course, inspired "129 Die in Jet," Warhol's last hand-painted canvas, and prompted his well-known "death and disaster" series. To compound Spieker's uncanny sense of "as if" ("as if the presence of these articles in Warhol's archive…commemorated an event… that had not yet occurred")-it seems as if the Concorde memorabilia acted as a study for a "death and disaster" print that never existed. According to Spieker, this experience within Warhol's archive suggests that "[a]rchives do not record experience so much as its absence; they mark the point where an experience is missing from its proper place," hence making them seem "haunted" (3).

<20> Similarly, Day, a project begun just over a year before the World Trade Center attacks, seems to record not contentlessness, pace Freind, but a spectral absence, a pathos for a trauma yet to happen: sandwiched between an article on the housing market in Queens and an advertisement for Radioshack is a small, unassuming piece entitled, "6 Real Estate Companies Submit Bids on 99-Year Lease for the World Trade Center" (177). The missing experience that this archival text records is what Hélène Aji cleverly (and cynically) calls the "terrifying…ready-made…of catastrophe." Even in retrospect, history is, so to speak, a given. To be sure, we can read this headline with a sense of ex post facto irony, yet the very mention of the World Trade Center also enables us to read it as an improvised textual memorial, a proleptic and poignant obituary for the building and its daytime inhabitants. The "content" of this archival trace, dependent as it is on the researcher's use of it, cannot exist in a vacuum (nor can it exist in a blank book). Furthermore, as a post-9/11 poem, Day is, I argue, far more powerful than, say, Galway Kinnell's "When the Towers Fell," which, in a pseudo-Whitmanian fashion, tries to synchronically catalog the economic diversity of the tragedy's victims: "The banker is talking to London. / Humberto is delivering breakfast sandwiches. / The trader is already working the phone. / The mail sorter has started sorting the mail" (52). The loose iambic/anapestic lilt, the plodding end-stopped lines, the consonance between "banker" and "Humberto": this is nothing other than what Theodor Adorno would call an "aesthetic principle of stylization…[that] make[s] an unthinkable fate appear to have had some meaning…[and hence] does an injustice to the victims" (198). Such intentional and contrived commemoration-placing imaginary toads in an imaginary garden (to adapt a famous phrase from Marianne Moore)-pales in comparison to the archive's uncanny "effect of the real"-that is, "the fact that [the archive] stores what was never meant to be stored" (Spieker 22).

Figure 1. Screenshot from the warhol: resources & lessons, a pedagogical website developed by The Andy Warhol Museum. <http://www.warhol.org/tc21/main.html>.

<21> There are, of course, actual rather than notional obituaries in Day:

Paul Yager, a veteran federal labor mediator who helped resolve several important labor strikes in the New York City region, died Monday at a hospital in Edison, N.J….He was active in 1984 in negotiations that led to a settlement of a 68-day strike by unionized workers against 11 nursing homes York City [sic]. (118)

This is to say if we look through Goldsmith's "magnifying glass"-zooming in on specific passages in this nearly 900-page text-we can apprehend that Day is, on the level of content, very much about labor (and the diversity of labor to which Kinnell strainingly pays tribute). Reading this long poem, we learn of an overqualified school teacher who was "turned away from a job fair in Queens…because she was certified"; she explains that school teachers are unfairly being reskilled under heteronomous conditions: "You have to be a combination of a social worker and Mother Teresa to work in…[New York City] schools…Those kids deserve a decent education, but we as teachers deserve a decent work atmosphere" (Day 180). We learn that workers at an Earthgrains Company plant "had walked off the job at the company's bakery in Nashville" (216), that "Bridgestone/Firestone face[d] a possible strike…by 8,000 workers at nine American factories" (197), that approximately "1,500 striking machinists at the Bath Ironworks shipyard…reached a tentative settlement with the General Dynamics Corporation" after agreeing "to allow General Dynamics to cross-train workers building complex ships" (216). Goldsmith's voluntary re-reporting of these various stages of employee refusal exposes the fundamental difference between the deskilled and alienated worker and the reskilled and autonomous artist; in the last example, General Dynamics' desire to "cross-train" workers is to make them more "swappable" not to reskill them (as Goldsmith reskills the task of poetry by crossing the activities of a secretary and copyright pirate). Additionally, we learn from Day that "[t]he nation's largest operator of welfare-to-work programs violated federal law by paying lower wages to women than to men placed in the same jobs in a Milwaukee warehouse." While the company, Maximus Inc., claims that women were being paid a "training wage" for inadequate job history, we learn that Tracy Jones, the woman who filed the complaint, has experience working "as a machine operator, a warehouse carton packer and a building maintenance worker" (Day 181). In Benjamin's sense, work here is being given a voice.

<22> Yet not only is the proletariat-what the Times calls "those without influence"-given a voice in Day. To take up Benjamin's notion of "polytechnic training"-the Yankees baseball star Derek Jeter (whose salary during his final season in 2014 was $12 million) demonstrates all too well that "the ability to describe a job in words now forms part of the expertise needed to carry it out." "My job is to score runs," says Jeter, "and that's the bottom line…I think everybody would like to hit more home runs, but, hitting first or second, that's not my job. As long as I'm getting on base, that's what I worry about" (Day 507). Of course, one of the virtues of Day is its "cross-class ventriloquy" (a phrase from a Publisher's Weekly review), its synoptic capturing of stories from many walks of life ("Day" 190). Yet if the "leveling of artistic and social hierarchies" (a phrase, again, from Publisher's Weekly) is effected only by virtue of poetic fiat (Tracy Jones, the warehouse worker, is on the "same level" as Derek Jeter, the celebrity athlete, in that both appear in the same poem), does the very presence of the likes of Jeter constitute "a distraction from the battle of real interests" (Adorno 188)? Such, indeed, might be the opinion of Nowak, who, in "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down," collages newspaper articles that expressly pertain to working-class rights. However, as I shift to a discussion of Nowak's docu-poetics, I don't wish to further entrench the enduring categories, famously theorized by Adorno, of "committed" and "autonomous" literature; Day, indeed, might be considered a work that "from…[its] first day belong[s] to the seminar…in which…[it] inevitably end[s]" while "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down" might be considered a work that "all too readily credit[s]…[itself] with every noble value" [11]. Rather, I wish to ground Goldsmith's and Nowak's commonalities on the level of archival capability, on the level of a reskilled methodology: a heuristic rapprochement between "the Sartrean goats and the Valeryan sheep" (Adorno 188).

"[R]epositioning poetic practice": Mark Nowak's Aesthetics of Amateurism

<23> In a rush of hyperbolic enthusiasm, Goldsmith argues that Day is, in actuality, a novel- "a great novel…filled with stories of love, jealously, murder, competition, sex, passion, and so forth." "It's a fantastic thing," he continues, "the daily newspaper, when translated, amounts to a 900-page book…And it's a book that's written in every city and in every country, only to be instantly discarded" ("Being Boring" 364). But New York is not Minnesota; Goldsmith's "readymade novel" produced in Duluth would be quite different in content from the novel produced in New York City. Nowak's "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down" tells a much more focused narrative as it is concerned with the personal effects of deindustrialization-specifically the shutdown of LTV Steel-on the local economies of Minnesota's iron range and thus culls material from newspapers based in northeastern Minnesota. It is a story, in part, about "competition," as Goldsmith claims, but not the kind of competition that has the entertainment value of an Andrew Agassi/Arnaud Clément tennis match. In a 2000 press release, LTV president Richard Hipple explains the shutdown of the company's operations:

The employees have done their utmost to maximize the performance of this mine. They are skilled, dedicated people. In spite of their efforts and LTV's investments of $20 million annually over the past five years, the quality of the LTV Steel Mining operations and ore reserves have deteriorated to noncompetitive levels. The mine's ore body stripping ratios and levels of impurities are too high and overall costs are no longer competitive.

In this case, the "maintenance-intensive" shaft furnaces of LTV are "not competitive with modern straight grate or grate kiln furnace operations, which produce better quality pellets at lower cost" ("LTV Steel Announces Intention to Close Minnesota Iron Mining Operations"). Hipple's comments suggest that the economic logic of deskilling has made his "skilled" LTV employees unemployable.

<24> In contrast to the LTV workers, Nowak, like Goldsmith, has the artistic freedom to reskill his poetic practice. This is a process that Nowak himself calls "repositioning":

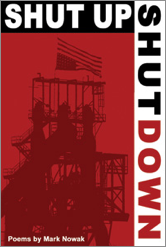

my new projects and new books participate not only in repositioning poetic practice ("make it new," if you will) but also participate in varied movements for social, political, racial, economic, cultural, and environmental justice at the same time. (qtd. in Clinton)

How exactly has Nowak reskilled or repositioned his compositional methodologies? To begin, Nowak's preference for the long poem can make us understand the extended sequence or poetic series as a deskilled form in itself. Clearly this is the opinion of the North American Review, a literary journal which boasts of being "the nation's oldest literary magazine." In reference to its Annual James Hearst Poetry Prize, its editorial staff offers potential submitters the following tip: "We have noticed that long poems rarely do well -- too much can go wrong in a large space" ("The Annual James Hearst Poetry Prize"). Such an attitude implies a Romantic/New Critical aesthetic that places supreme importance on poetic technique ("the most proper words in their proper places," as Coleridge famously stresses) as well as the unity and coherence of the artistic artifact (exemplified by Cleanth Brooks' "well wrought urn"). In short, the long poem is an invitation to error. Nowak's "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down," by contrast, relinquishes such received notions of poetic skill and utilizes the "large space" of extended poetic form to investigate specific socio-economic crises, the "too much" that goes wrong in the large space called the United States of America. The front cover of Shut Up Shut Down (as well as the title page of each poem) portrays an upside-down American flag (which is flown as a distress signal) indicating that "too much" is indeed going wrong in the communities of northeastern Minnesota [12].

Figure 2. Cover of Shut Up Shut Down.

<25> Additionally, photography plays a crucial role in "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down," which is a poem interspersed with thirteen black and white images of mostly LTV signs and vacant storefront windows from small Minnesota towns; one photograph shows an empty window displaying only a "Northland Realty" sign, suggesting the shutting down of the entire community. In contrast to Nowak's more recent Coal Mountain Elementary, a collaboration with professional photographer Ian Teh, the photographs in Shut Up Shut Down appear to have been taken by Nowak himself and have an unstudied, amateurish quality. Such a quality is accentuated by the fact that "$00 / Line / Steel / Train," the first series in Shut Up Shut Down, is, in part, an ekphrastic piece based on Bernd and Hilla Becher's Industrial Façades; perhaps Nowak chose not to reproduce the Bechers' photographs (which are internationally renowned) because they would have clashed with his aesthetic of amateurism. Yet rather than perceiving the amateurism of Nowak's photographs as an aesthetic flaw, we can understand it as a reskilling of the task of documentary poetry; in other words, a deskilled photography emerges as a reskilled poetry. In "The Author as Producer," Benjamin writes,

What we require of the photographer is the ability to give his picture the caption that wrenches it from modish commerce and gives it a revolutionary useful value. But we shall make this demand most emphatically when we-the writers-take up photography…only by transcending the specialization in the process of production…can one make this production politically useful; and the barriers imposed by specialization must be breached jointly by the productive forces that they were set up to divide. The author as producer discovers-in discovering his solidarity with the proletariat-simultaneously his solidarity with certain other producers who earlier seemed scarcely to concern him. (46)

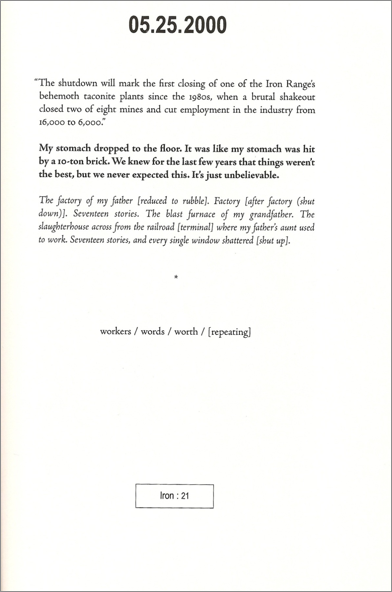

Figure 3. Image from p. 152 of "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down." The prose section on the following page ends with the description: " The smile plastic and purchased, community disembarked in the window" (153).

Nowak has quite literally "taken up photography" to make his mixed-media work "politically useful," and Benjamin's redefined conception of authorship shows the emancipatory potential of a reskilled poetry. Like Goldsmith, who celebrates the tasks of workers who were once of little concern to writers, Nowak repositions his poetic practice to trespass the specialization of production. Such repositioning is what Jules Boykoff calls Nowak's "strategic inexpert stance."

<26> Nowak is both amateur photographer and deskilled poet, yet the curious combination of image and text in "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down" fulfills what Foster considers to be a primary function of archival art: "to fashion distracted viewers into engaged discussants" ("An Archival Impulse" 6). The photograph, for example, on p. 152 (see fig 3) deepens the caption-like statement that is found on the previous page: "Windows® is shutting down…" (Shut Up Shut Down 151). As "engaged" readers, we note that Nowak's clever visual and homophonic punning allows us to recover an alternative syntactic reading-"Windows ® is shutting down…" as well as "Windows® [are] shutting down"-shifting our focus from the computer-based, informatized society we take for granted to the ailing local economies of post-industrial America. Nowak, in other words, sets up a dialectical tension between the computerized prompt and the "CLOSED" sign in the failed business' ("shut down") window. The smiley face in the storefront, like the polyvalent phrase "Windows is/are shutting down," indexes a jarring collision between big and small business and attests to the complex interaction between the poem's images and texts: the previous page repeats a union criticism that "'Wal-Mart'"-a corporation which unsuccessfully attempted to trademark the smiley face for use on store materials and employee uniforms-"'brings sub-standard wages and benefits to the area.'" I argue that Nowak-in Benjamin's sense-has wrenched the caption "Windows® is shutting down…" "from modish commerce"-and, by juxtaposing it with the photograph above, has given it "a revolutionary useful value."

Resisting/Remixing the Headlines: "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down"

'load every rift' of your subject with ore

-Keats to Shelley, 16 August, 1820

ore / pits / fill / with / water

-Mark Nowak, from Shut Up Shut Down

<27> In "Notes toward an Anticapitalist Poetics," Nowak says, "I…want to be able to imagine a future for poetry, as [Adrienne] Rich says, in 'Defying the Space That Separates,' 'not drawn from the headlines but able to resist the headlines'" (240). Here, Nowak and Rich are treating "the headlines" as a kind of metonym for the status quo, as a figure for the structures of power that perpetuate the injustices and iniquities of the present. I want to explore "the headlines" not as a metonym but as a textual substrate for poetry. In "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down," Nowak collages newspapers, remixing them in DJ-like fashion, precisely to resist "the headlines," to perform an immanent critique of the present. The poem is clearly about work, but less clear is the work that is embedded within the poem. In order to understand this, we first need to understand the long poem's elaborate structure.

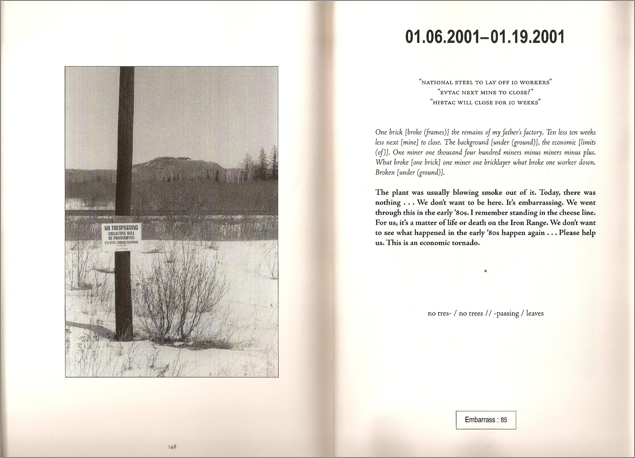

Figure 4. Page scan of p. 133

<28> To begin, the poem's prefatory material includes a note, an image, and an epigraph. In the note, we are informed: "The numbers that conclude each section correspond to workers who lost their job in that particular Iron Range community" (Shut Up Shut Down 130). Across the page is an image of the Hoyt Lakes water tower above a quote from Richard Hipple, the LTV Steel President: "It's important to note that this is not a people issue" (131). Within this context, Nowak's note becomes a "counter-note" as it exposes the disingenuous disavowal of Hipple's statement (which relies on a tautological, "business-is-business" logic) by reminding us of the number of people directly affected by the LTV shutdown [13]. Nowak exposes Hipple's statement as being nothing other than an example of commodity fetishism, which, according to Marx, supplants social relations with a relationship between things. We also better understand the serial structure of the work in that Nowak's note identifies a serial problem which affects not only Hoyt Lakes, where LTV was based, but also the communities of Iron, Tower, Virginia, Gilbert, Biwabik, Ely, Hibbing, Aurora, Embarrass, Babbitt, and Eveleth. In "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down" (as well as in "June 19, 1982," another long poem in Shut Up Shut Down), Nowak's basic unit of composition is the doublespread, which includes a photograph on the verso (such as the one in fig 3) facing a heterogeneous text of both prose and poetry on the recto (see fig 4 above); such a unit is iterated twelve times throughout the course of the poem advancing a working class critique of capitalist practices through accumulating contexts [14].

<29> Since the structure of the recto itself is quite complicated, I'd like to attend to its constitutive parts before discussing the ways in which the photographic images contribute to the text as a whole. A date in bold (such as "5.25.2000") tops the text-which corresponds to the date of the newspaper articles from which the section's content was drawn-followed by a prose section consisting of three parts: 1) a reportage-style paragraph in quotation marks which appears to excerpt a newspaper report or headline, 2) a paragraph in bold presenting first-person reactions to the LTV shutdown in free direct discourse, and 3) an italicized paragraph which most resembles a narratorial or even authorial voice as it frequently refers to Nowak's autobiographical experiences of growing up in working-class Buffalo [15]. This latter section is the most complex as it, too, contains quoted material-in one italicized portion, Nowak ironically cites the Emergency Broadcast System to indicate that the shut down is indeed an "actual emergency" (elsewhere it is described as "an economic tornado"): "'This is a test of the Emergency Broadcast System…If this had been an actual emergency…'" (139). While the quotes, boldface, and italics suggest three discrete registers of emphasis, the order of these parts constantly shifts from section to section, creating a weaving, choral-like effect. Below the prose, separated by an asterisk, is a line of haiku-like poetry (such as "workers / words / worth / [repeating]") which is often punctuated by virgules or other marks of punctuation and which often acts as a caption to the photo across the gutter. At the very bottom of the page is a box which encloses the name of a town (such as "Iron") followed by the number of laid-off workers.

<30> Nowak himself attributes the poem's distinctive structure to two different influences, the Japanese haibun, which mixes poetic prose description and haiku, and Marx's architectural metaphor of the base and superstructure. In an interview with Chicago Postmodern Poetry, Nowak says,

[The Chinese-Canadian poet] Fred Wah got me very interested in the haibun, and so my new book, Shut Up Shut Down, includes experiments with the possibilities of that form in relationship to photo-documentary, labor history, etc. In one of these serial pieces, "Hoyt Lakes/Shut Down," I wanted to see if I could find a way to replicate Marxist base/superstructure in poetic form; so I worked at developing haibun structures in which the ideological information at the top of the poem would balance precariously above the direct economic impact as base-represented by the number of taconite miners who lost their jobs in the Iron Range towns in northern Minnesota. ("Interview with Mark Nowak")

If the boxed number represents the Marxist base, then the superstructure would consist of the haibun, which is, itself, a two-part structure (prose writing combined with haiku). How, then, do we account for these two two-part structures in terms of Marxist theory? Marx's writings do suggest that the superstructure was comprised of two distinct tiers: 1) the state and 2) social consciousness. In the German Ideology, Marx and Engels argue that "the basis of the state and of the rest of the idealistic superstructure" evolves directly out of material production, and, again, in "A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy," Marx maintains that both "a legal and political superstructure" and corresponding "forms of social consciousness" arise from "the economic structure of society" (159-60). Yet it seems unfruitful to reductively align the poetry and prose of haibun with the state and social consciousness of Marx's superstructure. One suspects that Nowak's choice was motivated by the fact that the statistics below appear to be more "direct" and less "ideological" than the mix of different discourses presented above. In any case, I ultimately find Nowak's recourse to Marxist theory to be a red herring and while it may have acted as a productive starting point, the base/superstructure as a poetic model obscures the ways in which the poem's formal features actually operate and suggests unneeded oppositions [16].

<31> I'd like now to turn to Michael Davidson's essay "On the Outskirts of Form: Cosmopoetics in the Shadow of NAFTA" and his analysis of "05.25.00" to show how complex Nowak's poem actually is and to then clarify the poem's complicated issues of voice, structure, time, and place. Davidson spectacularly misreads this section, especially the italicized portion (see, again, fig 4 to situate this passage in context):

The factory of my father [reduced to rubble]. Factory [after factory (shut down)]. Seventeen stories. The blast furnace of my grandfather. The slaughterhouse across from the railroad [terminal] where my father's aunt used to work. Seventeen stories, and every single window shattered [shut up].

Here is Davidson's erroneous gloss:

Below this testimony by one of the laid-off workers is the schematic summary: 'workers/words/worth/[repeating]' which condenses the links between labor, language, and value in an alliterative sequence. Below this, outlined in black, is the word 'Iron' followed by the number '21', indicating that in the small town of Iron twenty-one workers lost their jobs. A photograph on the facing page shows the road to the main gate of the closed LTV steel plant. Each level of the poem deepens the 'base' by framing it in specific voices and images. (746)

Despite being one of our more savvy and intelligent readers of contemporary poetry, Davidson makes several puzzling errors here. Perhaps misunderstanding Nowak's Chicago Postmodern Poetry interview, Davidson initially appears to associate the Marxist base with the verse component of haibun while he links the superstructure with the prose description: "the relationship of prose to poetry replicates the classic division between superstructure and base, between narrative representations of 'real conditions' and the economic realities sustained by (or interpreted through) those representations" (745-6). Yet by the end of his analysis, both the prose and the poetry ("the schematic summary") seem to be different "levels," along with the photograph, which deepen the "base." The quotation marks are telling since it is unclear whether the base is now represented by the "Iron : 21" at the bottom of the page or if it is a loose metaphor for the "economic realities" of the iron range.

<32> My point is that this section, as well as the others in the poem, is less focused and coherent than Davidson assumes-that it does not represent a synchronic, topographic unity which can be "condensed" and "schematized" by neatly correlating frames which isolate a specific time (05.25.00) and place (Iron). Davidson simply thinks that the section "records the shutdown of the LTV steel factory in Iron, Minnesota" (746). The LTV taconite plant is actually located near Hoyt Lakes. Worse yet, the italicized "testimony" which Davidson attributes to a laid-off worker from Iron refers not to Iron but to Buffalo, New York (the "terminal" mentioned is New York Central Terminal). Moreover, the voice corresponds not to some laid-off worker but to Nowak himself. Throughout the poem, the italicized sections fragmentarily recount Nowak's working-class upbringing and make spatially-marked references to "Rejtan Street" (in the Kaisertown neighborhood of Buffalo where "Uncle Ray" used to play) (143), "General Motors" (an allusion to the GM Powertrain Engine Plant in Tonawanda) (135), and the "Westinghouse" plant where Nowak's father worked (137). The "blast furnace" referred to in the italicized passage above is the Buffalo steel mill where Nowak's grandfather worked (LTV's blast furnaces are located in Cleveland and Indiana Harbor) [17]. Thus, the primary action of the frame is not to "deepen" a localizable base, which acts as a kind of common denominator (elsewhere Davidson calls it a "bottom line"), but rather to offer one precarious component within a constellatory structure (746). The effect is more like a broadening or proliferation of contexts as we now understand the economic plight of the Iron Range in the larger context of what is called the Rust Belt-which stretches from Illinois to New Jersey-and we see the LTV shutdown and the events of May 25, 2000 as part of the longer durée of deindustrialization that has affected several generations of workers [18]. While Davidson's essay is surely sensitive to these contexts, his "stressing [of] a hemispheric frame" over "a kind of spiritual localism" and his attempt to study poetic production "created in the long shadow of NAFTA" (by putting Nowak into dialogue with the Mexican writer Cristina Rivera-Garza and the Canadian poet Lisa Robertson) ultimately deters him from clearly apprehending the local as he confuses Buffalo, New York for Iron, Minnesota (735-6). Not only that: Davidson is also missing the very important local choices that Nowak made in the process of composition by privileging the neologic rubric of "cosmopoetics" [19]. To fail to grasp the fact that many of Nowak's sources are newspaper sources diminishes the crucial concept of Benjamin's polytechnic training that underwrites Nowak's poetics and overlooks the labor embedded within "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down"-the poem is not only a tribute to the steel workers of LTV but to the important labor of journalists that "repeat" (and "give voice" to) the reports of the workers. Indeed, Nowak's 2011 blog post "New Labor Journalism and the Poets" makes his indebtedness to journalists abundantly clear.

<33> And while Davidson claims that the base is framed by "specific voices," the specificity of many of the voices remains indeterminate due to Nowak's aggressive use of free direct discourse (the presentation of speech without any narratorial mediation or use of tag clauses) [20]. Davidson assumes that the bulk of Shut Up Shut Down was based on "interviews with workers" (and surely Nowak's formulation "workers / words / worth / [repeating]" invites such a view), though many of the voices presented in bold are not actually from the taconite miners who lost their jobs but rather come from newspaper quotations representing a range of people [21]. Here, David Ray Vance's caveat that "Nowak's use of textual documentation reinforces…[a] sense that we're not getting the whole story" is particularly germane; he states, "short of doing the legwork of tracking down the original sources, we simply can't know" which materials came from which sources thereby inviting a "skeptical inquiry" of the presented materials (348) [22]. If we re-examine page 133 (again, see fig 4), the paragraph in bold appears to represent a single worker's "testimony":

My stomach dropped to the floor. It was like my stomach was hit by a 10-ton brick. We knew for the last few years that things weren't the best, but we never expected this. It's just unbelievable.

If we consult, however, the poem's "Works Cited" of some twenty newspaper articles and do our due diligence in performing the detailed "legwork" in the various archives of local newspapers (most of which are conveniently digitized), we realize that this boldface block is a centaur construction-the first two sentences come from Marlene Pospeck, the mayor of Hoyt Lakes and the last two sentences come from Jerry Fallos, president of United Steelworkers of America Local 4108 in Aurora [23]. I repeat: the only way to know this is to consult such publications as the Duluth News-Tribune, the Mesabi Daily News, and the St. Paul Pioneer Press and to painstakingly crosscheck the articles alongside Nowak's poem. Here, we sense an axiom of archival poetry: that archival poetry, if successful, leads its readers on a ramifying search through the archives with a skeptical eye toward documentation-that is, the value of archival and documentary poetry is not strictly informational but rather lies in its ability to suggest a particular methodology or practice of skeptical inquiry and research. In any case, the words of the laid-off workers from Iron, MN are not represented here as Davidson suggests-neither in the italicized nor the boldface sections. We thus grasp the limitations of Nowak's sources in that the newspapers seem much more inclined to interview and cite more visible figures (such as the mayor and union president) rather than the unemployed laborers [24]. To be fair, Nowak does "repeat" the words of workers in other sections (the "Aurora" section cites Dale Walkama who endured two mining accidents), yet they don't always directly correlate to the LTV layoffs let alone the community represented at the bottom of the page. For instance, in the section which is "based" on the town of Ely, Nowak fuses the words of Matt Tichy, a sales manager of a welding supply firm in Virginia, with the words of Jim French, a manager of a lumber company in Aurora:

The biggest thing is that it's going to have a trickle-down effect. It will affect everyone, from grocery stores to gas stations. It affects everybody up here. But it's happened before and we made it through it. We're fighters up here. You make it through those lean years and you go on. (143)

In the passage above, the first three sentences are Tichy's and the last three are French's. If Nowak's poetry gives "voice to constituencies seldom freed by free trade," as Davidson claims, it appears that his use of free direct discourse strips them of their individuality-particularly in the way one voice rapidly cuts to the next without any distinguishable shift (739) [25]. Committed literature, according to Adorno, "renders the content to which the artist commits himself inherently ambiguous," and the blurring effect of the voices surely contributes to a sense of ambiguity. Yet, if we consider Nowak's intention to tell "a group narrative," as Adrienne Rich points out in her back cover blurb, and place this poem within an epic or, better yet, "pocket epic" tradition, we better understand his use of boldface to smooth over the collaged "cut" (in the example above, the "cut" occurs between the third and fourth sentences) as a means to achieve and present a collective voice (190) [26]. In this sense, Nowak's sentiment matches Matt Tichy's observation that this issue affects "everybody up here"-hence the choice to include a range of voices from a variety of locales.

<34> My larger argument is that it is far more productive to read "Hoyt Lakes / Shut Down" with a close attention not only to its "intangibilities of form"-the way it, like Goldsmith's text, brings both productive and artistic labor into view-but also to its genre and formal techniques (such as unconventional punctuation and typography) rather than by focusing on the misleading metaphor of "the base" which tends to falsely orient each section of the poem toward particular voices (of unemployed workers) in particular places (like Iron or Hoyt Lakes). The almost obsessive use of punctuation-particularly in the italicized sections and the haiku-counterbalances the free direct discourse of the boldface sections in which voices indiscriminately mix without attribution. Likewise, the asterisk which punctuates each recto of the doublespread indicates that there is a missing component, that we are dealing with an "inadequate" descriptive system [27]. (Elsewhere, Nowak deploys the asterisk to make a witty and pointed critique of capitalism: "'in God we *rust'"). Nowak's liberal use of brackets betrays an anxiety that something is always being left out, since brackets, after all, are used to enclose explanatory or missing material. The phrase "workers / words / worth / [repeating]," on closer inspection, seems to acknowledge the lack of the workers' words in the prose structures above, and the bracketed intrusions can be read as Nowak's desire to fill in that lack. Since he doesn't include an apostrophe in "workers," we can perhaps understand the phrase to mean "words on behalf of the workers are worth repeating." The virgules which separate each word call attention to the mediation of the text (and the articulated spaces that exist between every grapheme), suggesting that this is a rewriting of several lines of poetry in paragraph form. I'd like to propose that this is a deliberate move on Nowak's part, which behooves us to question, in a similar fashion, the mediated nature of the blocks of prose. In other words, the poem is teaching us the "skeptical inquiry" which Vance mentions-that we should not make hasty assumptions about the documents presented in the poem. In this manner, we should even question the way the book is presented on the publisher's website, which describes the pieces of Shut Up Shut Down as "poetic oral histories" rather than newspaper collages ("Shut Up Shut Down").