Reconstruction Vol. 15, No. 1

Return to Contents»

Dress You Up in My Angst: Living with the Past in Français 2646 / Brendan Sullivan

Abstract: In this article I describe an encounter with a fifteenth-century manuscript and its assertive "fifteenth-century-ness," as exemplified by the style of dress in this manuscript's miniatures. While this historical specificity would normally offer a premise for reconstructing the past, I instead feel a powerful sense of difference and distance. Try as I might, I cannot "fit" into clothes in this manuscript's images, as they are tailored to the life of different person in a different time. This temporal self-consciousness leads offers an alternate way of thinking about the historical meaning of this object: I narrate how this manuscript might manifest the desires and anxieties of its patron, in tandem with my own emerging anxieties and frustrations as I attempt to understand the past.

Keywords: Fifteenth-Century Flemish Manuscript Illumination, Costume History, Anxiety, Failure

You've Got Style, That's What All the Girls Say

<1> Look at this miniature, found on folio 176 in the illuminated manuscript Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscrit français 2646 (Figure 1) [1]. This manuscript contains Book Four of Jean Froissart's Chroniques, a chronicle of England and France during the Hundred Years War, with the fourth and final book in the Chroniques covering a period stretching roughly from 1389 to 1400. This particular manuscript of Book Four was produced in Bruges in the 1470s, as part of a complete set of the Chroniques commissioned by the Burgundian noble Louis of Gruuthuse [2].

<2> I saw in person this manuscript, and this miniature within it, for the first and only time on a day in June 2012. This essay is about what happened when I looked at this miniature, as well as what happened (and might have happened) before and after I looked at this miniature. But before I describe this encounter, I need first to describe what this image illustrates. It appears at the beginning of a chapter in which Froissart relates a disaster commonly referred to as the "Bal des Ardents," or "Dance of the Burning Men" [3]

<3> During a 1393 celebration at the Hôtel de Saint-Pol for the wedding of a knight and one of the French queen's ladies-in-waiting, Charles VI, then king of France, decided that he and five of his closest noble friends would dress up as "wild men," donning elaborate costumes made of linen and pitch, and then dance, incognito, for the delight of those gathered for the wedding. The performance began as planned, with the king capering around the room, leading his five compatriots around by a chain. Unfortunately, when Louis, Duke of Orleans and brother to the king, approached the dancers while holding a torch, an errant spark caught on one of the dancer's costumes. Due to the dryness of the linen hair-suits and the close proximity of the dancers, this fire rapidly spread to five chained dancers. The Duchess of Berry, the king's aunt, had identified her nephew earlier in the dance, and so quickly wrapped him up in her robe to protect him form the fire; the son of the Lord of Nantouillet rushed into the wine cellar to immerse himself in a large vat of water. These two were only survivors: the four other dancers died "in great pain and suffering" (Froissart 4: 178; ch. 32) [4]. According to Froissart, the news of these events quickly spread through city, shocking the Parisians with the tragic consequences of the king's decadence. Both Charles VI and his brother Louis were compelled to make a pilgrimage to Notre Dame in penitence for their irresponsibility

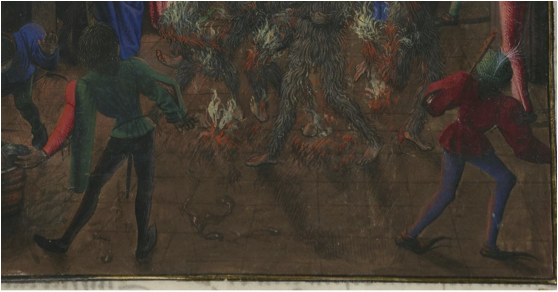

<4> The rendition of the scene in fr. 2646 drenches its actors in darkness and confusion, the figures all orbiting around the group of burning men (Figure 2). Royal spectators are arranged in an arc across the background of the image, viewing the scene with various expressions of horror. Charles VI, wrapped in the Duchess of Berry's blue robe and attended to by a man in a black gown, watches the other dancers, in wide-eyed shock. Moving rightward across the arc of figures, we find a woman - most likely the queen - lavishly dressed in a gold brocade robe and jeweled hair horns. She clasps her hands and closes her eyes, apparently fainting into the arms of her ladies-in-waiting. A male courtier raises his hands and opens his mouth in response to this terrible accident.

<5> The musicians on the top of the viewing stand in the upper right of the miniature have stopped playing, their performance interrupted by this grim spectacle. A few figures peer out from underneath the viewing stand, while a noble holding a torch rushes toward the dance floor. In the foreground, several courtiers are shown with their backs facing the viewer. This rear view is repeated throughout the miniatures in fr. 2646, likely to create a sense of spatial depth - but here, the deeply shadowed backs of these figures contrast with their brightly illuminated front, emphasizing not just space but the heat and light generated by the fire blazing further into the image. Two men fill buckets with the water from a basin to help the burning men, while one wild man, likely the son of the Lord of Nantouillet, staggers off to the left, heading in the direction of a raised curtain indicated by another man holding a torch. The burning dancers are at the center of this swirl of onlookers, chained together and woven into an agonized thicket of contorted poses. Flames lick at their clothing and cast terrible shadows on the rest of the miniature. Almost all the surrounding figures in this scene turn their attention to the dancers; this central group glares out at the manuscript's viewer, as if the pupil of some giant eye.

<6> I say "eye" because, when I saw this miniature in person, it seemed as if I was not only looking at this image, but that it was looking at me - staring across immense intervals of time and space, waiting to see what I would do. I had to figure out why it was confronting me like this, to explain or understand why this manuscript engaged me so. It felt like something had to happen.

<7> But it might be unfair to attribute this explanatory pressure, this sense of attentive watching, purely to some auratic quality within the object itself. The conditions surrounding my visit to the BNF, a visit arranged specifically to see fr. 2646, likely also contributed to this acute sense of expectation.

<8> This is probably obvious to my reader, but I didn't spontaneously decide to see fr. 2646, contact the BNF for permission to see it, and then jet over to Paris. Rather, I first encountered fr. 2646 through the scholarly literature on this manuscript, as I searched around for a dissertation topic [5]. Specifically, I first read about fr. 2646 in the article "The Illustration of Book Four of Froissart'sChroniques: The Relationship Between Text and Image" by Laurence Harf-Lancner and Laetitia Le Guay, published in a 1990 issue of Moyen Âge [6]. As part of the article's larger discussion of the manuscript copies of Book 4 of the Chroniques, the authors compare different renditions of the one event that is universally illustrated across the different manuscripts: the Bal des Ardents. Harf-Lancner and Le Guay identify the image of the Bal des Ardents as one of a class of "dramatic scenes" that occur in the various Book Four manuscripts, scenes "in which blossom a 'macabre' aesthetic characteristic of the fifteenth century" (102) [7]. Among these dramatic images in the different Book Four manuscripts, none is more dramatic than that in fr. 2646: "The painter of [fr. 2646] does particular justice to the dramatic intensity of Froissart's retelling. All is disorder, agitation, and confusion in this scene in somber colors, brightened by the few large red patches of tapestry, here inseparable from the theme of fire" (105) [8]. Their analysis leads to this general characterization of the miniature: "[fr. 2646] distinguishes itself easily from the others by the force and violence of its images" (105) [9].

<9> As I read, I was struck by this last description: what were words like "force" and "violence" doing? They seemed to point to a visceral, affectively impactive power that the manuscript exerted over its viewers, both past and present. Although created in the fifteenth century, these miniatures must have seemed forceful or violent when Harf-Lancner or Le Guay looked at them some time in the late 'eighties or early 'nineties - otherwise, why would the authors have thought to use these words to describe them? Yet this was not "force" and "violence" just as a subjective, a-historical emotional response to this image - as suggested in the above citations, the force, violence, drama, and so on in fr. 2646's miniature of the Bal des Ardents are symptoms of the conditions surrounding the manuscript's creation. The miniatures are this way because of a "'macabre' aesthetic characteristic of the fifteenth-century," or because of the artist's ability to do "particular justice" to the forceful and violent qualities inherent in Froissart's text.

<10> Harf-Lancner's and Le Guay analysis of the miniature on f. 176 presented me with two interlocking expectations for my experience with fr. 2646: this experience would be emotionally impactful, but it would be so in a way that was historically productive, that pointed to some aspect of fr. 2646's original historical context. This combination of first-hand impact and historical meaning was further reiterated by much of what I read about fr. 2646: this manuscript and its images are deeply emotionally expressive, only as the effect of a historically specific cause. This all suggested that meaning, as it emerges from this manuscript, should be derived from some aspect of its fifteenth-century creation, specifically the desires or actions of some person involved in that creation. So there was a dual pressure placed on me by this scholarly precedent: not just that the manuscript be meaningful, but that it be meaningful in a way that satisfied certain standards of historical significance and fidelity. Moreover, the collected knowledge that I read through offered ample evidence that other scholars had found this manuscript to be meaningful, which placed greater pressure on me to find some kind of new meaning that would result in my inclusion among their ranks.

<11> The historiographic importance of this meaningful emotional response placed further emphasis on a particular kind of experience as the source for this response: an experience derived from an encounter with the original work of art. Before arriving at the BNF, I had some basic familiarity with the visual contents of fr. 2646, as I had seen miniatures reproduced either online or as illustrations for the various scholarly discussions of the manuscript. However, I had refrained from making any definite conclusions about the meaning of fr. 2646 based on these reproductions. The art historical method I absorbed prioritized the original work as the best, most reliable source of historical information, and gave further reproductions of this original a secondary, marginalized role [10]. Reproductions could effectively serve as illustrations to an art historical text, but not as the source of the arguments or conclusions advanced within that text. These should be derived from the original - really, could only be derived from a careful, attentive experience with the original object.

<12> As historiographically important as the original was (or perhaps because the original object is so important and materially rare), I also knew that my time with this manuscript would be limited. When I finally reached out to the BNF to ask for permission to view fr. 2646, the library conservators allowed me one day to view the manuscript; after that, it would vanish back into the vaults. Aware of how short my time with this particular book would be, I tried to be as well prepared as possible, in order to make the most of my brief encounter - to make sure that something happened. I carefully re-read the scholarly work on fr. 2646 I had already read, and then read whatever I hadn't, so there were no gaps in my knowledge. I would be fully equipped to deal with whatever fr. 2646 offered to me.

<13> Between my years of training and preparation, the historiographic importance of the original object, and my limited access to this particular manuscript, my trip to the BNF felt as much a pilgrimage as a professional necessity. I had been thinking about this manuscript for so long, had crossed such a substantial distance at great expense, and had to communicate in a secret language (French) in order to see it: all this and more combined to make overwhelmingly intense my desire for something deeply historically meaningful to spring from fr. 2646 when I finally sat down to view it.

<14> So here I was, in front of this one image that had for so long sat at the center of my research, whose reputation for distinctive affective force had provided the impetus and inspiration for my entire dissertation project; an image that, I hoped, would accordingly lead me to some kind of conclusion for that project, to understand why this image was so "forceful" and "violent." But as I looked at it, what I had anticipated was precisely what felt most glaringly absent: some kind of conclusion, some definite sense of what this image was meant to mean, how it reflected the needs and desires of its fifteenth-century audience, or the agency of some fifteenth-century artist.

<15> As I continued to look at this miniature, at the depiction of these suffering men, I began to look less at them, and more through them, to something in the background. I saw, through the mesh of burning bodies, a green shoe (Figure 3)

<16> I had never noticed this shoe before. In this sense, some of expectations I brought with me to the BNF were satisfied: in looking at the original, I had an experience that was distinctly different from that which emerged when I looked at reproductions. This shoe was worn by the woman in a pink robe directly behind the burning men, standing with her hands clasped in front of her skirt (Figure 4). Paying greater attention to her, I noticed that this green shoe wasn't just haphazardly green, but matched her green belt. Further, other small details emerged in her dress: for example, she bunched her robe up under her arm, while the other women around her let their robes fall free; the patterns drawn on the brocaded cuff and neck of her gown were different from those of the women next to her; she wore a necklace made of black stones (onyx?) set in gold, unlike the thin gold chains worn by the other women. But it is the shoe that seems the most unlikely, even extraneous detail, placed where it would barely have been noticed - yet it was also something that would have required a certain amount of artistic attention, or anticipated viewer interest, to be incorporated into this image in such a coordinated way.

Satin Sheets, and Luxuries So Fine

<17> Who cared if this shoe was green? Further, why would it matter that this shoe be green at its particular location in the image, behind a writhing mass of burning bodies? Perhaps this is a ridiculous question, too focused on a small, ultimately trivial element of this image. But it is still a pressing question, or at least the best question I can think to ask in the aftermath of my encounter with fr. 2646. After all, the circumstances surrounding this shoe's inclusion in this miniature are the same as those normally used to divine the meaning of an image: someone, in an intentionally directed action, put the shoe there. Some agent's desire - the patron's, the artist's, whoever's - is responsible for this shoe's existence. Furthermore, I noticed it: its noteworthy greenness became part of the relationships forming in my mind between text, image, historical context, and myself. Aren't these the basic conditions that I discussed earlier in this essay to explain why and how something is historically meaningful? Wouldn't this make the shoe meaningful in itself, an object capable of bearing and producing meaning? If so, what might this green shoe mean?

<18> To eliminate one possibility immediately, this shoe isn't a direct illustration of the text: in other words, it isn't there as part of a visual "transcription" of the past as described by Froissart in the Chroniques. The hair-suits worn by the dancers are the most carefully described garments in this chapter: the equerry "acquired six canvas tunics, […] had frayed linen brought forth and strewn over them, and covered the tunics with frayed linen in the form and color of hair" (4: 177; ch. 32) [11]. Of course, the other significant piece of clothing described in the text is the gown worn by the Duchess of Berry, which she uses to save the king's life. But there is no mention of a green shoe, or other specific details of costume.

<19> If these details are not taken directly from the text, what then could be the source for this particular shoe? Based on what I've read, both about fr. 2646 specifically and medieval manuscripts generally, I would assume that the answer to this question can be found by looking to the fifteenth-century context in which this object was made - that is to say, by using historical contextualization to shoe-horn myself further into the reasoning behind this image. Conveniently for my contextualizing desires, clothing style is one way that this miniature links up with its context. Along with the rest of the garments in the miniature, it is likely that shoes like these would have been familiar to fr. 2646's patron Louis of Gruuthuse as part of the late-fifteenth-century clothing he encountered in his everyday life. For example, the short doublet worn by the figures in the foreground with their backs turned to the audience seems to have become fashionable in the 1450s and 1460s, and remained generally so at least through the 1470s. The clothing worn by the women in this image equally exemplifies the style of feminine dress current in the late fifteenth century: gowns with a wide band of velvet at the hem and tightly compressed, triangular bodices; deep "v" necklines edged in velvet with a black gorget covering the lowest part; the tall, conical headpieces referred to as hennins [12].

<20> So, to sharpen my previous question: why does this fifteenth-century shoe appear in an illustration of a fourteenth-century text? As I ask these questions, I worry that I'm overstating how "confusing" I found this shoe to be, or at least how confusing a fifteenth-century shoe was as the illustration of a fourteenth-century text. After all, this temporal discrepancy - with garments "updated" to reflect those in style at the time of an image's creation - has long been recognized as a characteristic feature of medieval depictions of the past. The question of how the Middle Ages visualized the past has been much discussed in recent years, receiving monumental treatment in "Imagining the Past in France," an exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2010-11 of French (and some Flemish) historical manuscripts from 1250 to 1500. Clothing is instrumental to this catalogue's historical goals, helping art historians articulate how historical manuscripts were thought to work, how they reflected and reinforced a particular understanding of the past.

<21> In an essay in the "Imagining the Past" catalogue, Anne D. Hedeman - one of the exhibition's curators and the foremost authority on medieval French visualizations of the past - describes the function of "contemporizing" clothing (i.e. updated to reflect styles current at the creation of a given image) as follows:

to make the past come alive and be relevant to readers and viewers of manuscripts in the medieval present. In these works artists drew on a system of signs based on the representation of contemporary dress that were readily recognized by medieval viewers. Artists represented actors in historical events from the distant past in contemporary medieval guise, and the familiarity of their dress immediately established the social or moral sphere that they inhabited. (Hedeman 78)

<22> Hedeman does not reveal a long-ignored aspect of medieval visualization; rather, as is appropriate in an essay in a catalogue surveying medieval French illuminated history manuscripts, she summarizes and articulates one of the central hermeneutic convictions guiding the art historical interpretation of medieval visualizations of the past. Following this mode of thought, the appearance of a fifteenth-century shoe in fr. 2646 can be understood as part of a larger visual effort to make Froissart's fourteenth-century text more accessible to a fifteenth-century reader, namely by representing the fourteenth century in a way that would have drawn on details the reader would have recognized from his everyday experience. In other words, rather than attempting to represent that past as "past," temporally and culturally removed from the fifteenth-century reader, this green shoe and other anecdotal details make the events depicted in this image seem more "present," experientially and temporally co-extant with the viewer.

<23> This model implicitly informs much of the scholarly work on the images in fr. 2646. For example, Olivier Ellena has connected the unusual violence that characterizes the illuminations of this manuscript (as well as those illustrating the other volumes of the Chroniques commissioned by Louis of Gruuthuse) to the larger social and political concerns present in Louis's milieu. In particular, Ellena sees this violence as a reflection of the growing instability of the noble class in the Burgundian Netherlands:

[T]he fourteenth-century events reported by Froissart, translated into images in the years 1470-5, served as a historical foundation for the social upheaval that, at the end of the Middle Ages, led to the noble class's definitive loss of immunity. At the moment when the government of Charles the Bold was proclaiming Justice to be the "principal thing" and practicing coercion by force, Louis of Gruuthuse, actor in and spectator of the curial milieu, searched for the sources of this violence in the examples provided by Froissart. (Ellena 68) [13]

Ellena imagines Louis looking to the fourteenth century to explain the characteristics of his fifteenth-century present; following the model articulated by Hedeman, this search for fifteenth-century meaning is facilitated by the use of fifteenth-century dress.

All Your Suits are Custom-Made in London

<24> All this seems like a reasonable explanation for the green shoe. It was this general kind of explanation that hovered over and around me as I looked at this image of the Bal des Ardents, increasingly fascinated by the green shoe lurking in the background and striving to attribute some specific meaning to it. Yet, although I don't disagree with interpretations such as Ellena's and Hedeman's, I feel uncomfortable making a similar one myself, one that claims to uncover the original meaning behind or within this particular miniature in fr. 2646. If I don't disagree with these interpretations, it might be more accurate to say that I am unsympathetic to them, because my own experience with this manuscript was so different.

<25> When I saw this image, and felt this green shoe attract more and more of my attention, it didn't seem like I was uncovering a secret clue to this manuscript's hidden meaning. Rather, as I stared at this shoe, I increasingly felt the absence of such meaning, felt the effortful, even artificial nature of any attempt on my part to make such historical interpretations. I felt, finally, awkward in front of this manuscript, sharply aware that, however much historical knowledge I might accumulate in view of contextualizing this book, I, on a fundamental level, did not "fit" into this manuscript.

<26> In one sense, this difference is painful, as any ill-fitting garment would be - there was a sense of shame, or of disappointment that I was unable to take on the habitus of a fifteenth-century viewer, and thus to feel as if I had accomplished the basic set of disciplinary tasks set out for me. But, since this sense of disappointment is what emerged in my encounter with the manuscript, perhaps some kind of historical meaning - something that at least seems historical in staging a connection between a past and a present - would appear if I work at this disappointment a little more. After all, there has been a growing scholarly interest recently in failure as a productive critical strategy [14].

<27> Acknowledging the specter of Bordieu that was summoned by my mention of "habitus" in the previous paragraph, I think it is worth exploring how this green shoe is distinctive, how familiarity with this shoe "unites all those who are the product of similar conditions while distinguishing them from all others" (Bordieu 56). Certainly, this sense of distinction is already present in the earlier citation from Hedeman [15], inasmuch as she takes it for granted that fifteenth-century clothes establish a series of meaningful moral and social differences that would be readily grasped by a fifteenth-century audience. But, while art historical analysis assumes that these clothes created a connection between the fourteenth-century past and fifteenth-century present, might this analysis also underestimate how much these fifteenth-century clothes eliminate or frustrate other kinds of connections?

<28> What kind of socially structural work did fashionable clothes do in the fifteenth-century Burgundian court, the court in which Louis of Gruuthuse, patron of fr. 2646, was a participant? Susan Crane, in her book Performance of the Self: Ritual, Clothing, and Identity During the Hundred Years War, suggests

the innovations around fine clothing gave it a social importance comparable to the high profile of coffee and chocolate in the late seventeenth century, or television sets in the mid-twentieth century … the changes that prepared for clothing to become such a highly charged product by the mid-fourteenth-century were the establishment of an Italian silk industry, long-distance trade in furs and oriental fabrics, and tighter, more flexible weaving in northern European fabrics that made possible form-fitting garments. (Crane 13)

These changes in both the materials and techniques available for the creation of late-fourteenth and early fifteenth-century clothing led to a doubling of its social importance, both through the explicit regulation of sumptuary laws and the more subtle distinctions of fashion. Crane argues "since sumptuary regulations were largely unenforced in England and France, Alan Hunt may be correct that they are more 'declaratory' than proscriptive, aiming at 'ensuring recongizability' rather than at constraining consumption. In that case, sumptuary regulations and fashion trends would be hand-in-glove assertions that clothing expresses social stranding" (15).

<29> The Burgundian court, although operating a few decades later and a little further north than the French examples studied by Crane, was very similar in its sartorial culture, if not even more intense in its obsession with status. Margaret L. Scott, examining the role of dress in visualizations of Charles the Bold (Duke of Burgundy from 1467 to 1477), indicates "there is … clear evidence, both visual and documentary, that the general level of ostentation in dress increased dramatically under the dukedom of Charles the Bold" ("The Role of Dress" 44). This ostentation was an important part of Charles' role as Duke of Burgundy, since "Charles was a part of a world that regarded magnificence as a princely duty" ("The Role of Dress" 52).

<30> While certainly not carrying the same political obligations and responsibilities as the Duke, the other members of the Burgundian court were equally part of this politically loaded display. Marina Belozerskaya, writing on the larger European perception of the Burgundian court, suggests "the magnificence of the dukes and their court was calculated to broadcast their authority and eminence to their subjects, allies, and adversaries. The attainment of this objective is manifested in numerous contemporary documents" (Belozerskaya 53). The "fashionable" clothes worn by the figures in fr. 2646 were not just neutral, practical aspects of everyday existence, but deeply enmeshed in a larger system of social inclusion and exclusion. Belozerskaya notes "clothes defined a man (and a woman): the intrinsic value of clothing was high, and the ability to invest in the most refined materials was limited to those of the highest rank" (121).

<31> The social distinctions operating through the clothes in fr. 2646 were likely further reinforced by the medium in which these distinctive garments were visualized. Manuscripts were also a form of socially meaningful consumption, as much if not more than clothing. Manuscript production in the Burgundian territories exploded when Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy from 1419 to 1467, began to rapidly acquire luxurious illuminated books after 1445. Other Burgundian nobles followed his example and began to accumulate their own libraries, with their commissions reflecting Philip's own literary preferences; Louis of Gruuthuse's library is no exception to this pattern [16]. This explosion of manuscript patronage, radiating out from and modeled on the Duke at the center of Burgundian culture, suggests that the commissioning and possession of manuscripts were another way members of the Burgundian court could demonstrate their inclusion within a cultural elite. Hanno Wijsman has argued in Luxury Bound, his study of Burgundian manuscript patronage, that "a member of the highest elite in the Netherlands under the Burgundian-Habsburg dynasty was evidently expected to evince a degree of bookish interest … The commissioning and owning of manuscripts, particular [sic] illustrated luxury manuscripts, was a fashion, an essential" (524) [17].

<32> Français 2646 was thus an object deeply engaged, in multiple ways, in a culture of conspicuous consumption. Its demonstrative luxury, and the fifteenth-century garments that populate its images, collaborate to demonstrate and reaffirm the social status of Louis of Gruuthuse, its original owner. I think this demonstration of status, its implied distinction between those who share Louis's status and those who do not, is itself an important part of how this manuscript becomes meaningful. This might, at least in part, offer one justification for my sense of "difference" from this manuscript - after all, I do not dress as a late fifteenth-century Burgundian noble, do not have the money to commission such a manuscript or an equivalently luxurious object, and thus cannot make this immediate and familiar kind of connection.

But I've Got Something That You'll Really Like

<33> However I don't think this explains everything. If it was only this difference in knowledge, in my familiarity with a particular stylistic code, I suppose this problem could be at least partially remedied through the accumulation of the proper historical context. But, as I have already said, this kind of contextualization, created with the intention of entering into the miniature, seems unsatisfying: it does not completely account for my experience with the manuscript. There was something else in my sense of difference, something focused not on social or material distinctions, but instead on a temporal one. Yes, this manuscript addressed me as someone who was not Louis of Gruuthuse's social equal - but I think it also addressed me as someone not his temporal equal, someone in the future of this manuscript and thus with a markedly and meaningfully different relation to it.

<34> Would Louis of Gruuthuse have thought about the future, about later readers and viewers of his manuscripts? This consideration of other time periods, of the past and future as well as the present, is implicit in the historical specificity of dress in fr. 2646. Fifteenth-century Burgundian culture was certainly aware of the transient nature of styles of dress. Anne H. Van Buren points out in Illuminating Fashion that the changes in style were often documented both visually and textually, and were frequently placed in a chronological and comparative relation with each other: for example,

[The Burgundian writer] Olivier de la Marche said so explicitly in his Parement des dames, in describing women's headdresses he had seen since his birth around 1426. After declaring that he preferred the simpler headdresses of his time, the early 1490s, he described the previous styles: the high conical bonnets of the 1470s and early 1480s, the banner headdresses of the 1450s and 1460s, and the tall-horned temples, hennins, of the 1430s and 1440s. (Van Buren 19)

<35> In addition, Van Buren points out occasions when slightly outdated forms of dress signaled a temporal distance between the illustrated past and the fifteenth-century reader:

The Flemish illuminator Jan de Tavernier made a remarkably systematic use of outmoded dress in … the Cronicques et conquests de Charlemagne … while the frontispiece, a charming picture of life in a Flemish town … is an authentic document for men's fashion in the late 1450s, all of the following miniatures - illustrating the history of Charlemagne - show actors in the style of around 1400 or later. (Van Buren 24)

According to Van Buren, the "outdated" clothing would have suggested to the viewer a temporal difference between themselves and Charlemagne. Moreover, these "historical" garments could have been based on the artist's familiarity with older images, on an empirical awareness of difference: Van Buren further suggests that this "1400s" dress would have been modeled after works in Philip the Good's own collection, "which included several richly illustrated history volumes made around 1400 for Philip's grandfather, Philip the Bold" (24).

<36> This attention to changes in style over time offers a further nuance to the way fr. 2646 might indicate the status of its owner, specifically how it might try to preserve that status into the future. I say "preserve," because I think the question of preservation and suppression over time is unavoidably implied by the historically specific clothes in fr. 2646. My citations from Van Buren demonstrate that fifteenth-century viewers were aware that the style of dress in the later 1400s was different from how people dressed in previous decades or centuries. Yet, within this explicit articulation of stylistic change from the past into the present, I think there is another, implied temporal horizon: change will happen again, and how people dress now, in the late 1400s, will inevitably be different from how people dress in the future.

<37> A consideration of the future may be an unavoidable implication of fr. 2646's fifteenth-century clothing; this offers one reason for an affirmative answer to my earlier question about whether or not Louis would have thought of the future. But this affirmative leads me to restate question: if he was aware of the future, of future viewers, would Louis have cared about these viewers? Would it have mattered to him that some unknown person in the future might look at his manuscript, and attempt to understand why it is illustrated in the way that it is?

<38> I think the answer to this question is: yes, Louis would have cared. He would have cared about future viewers, because this future might have seemed like a threat, particularly to fr. 2646's ability to commemorate Loui's intertwined social and historiographic agency. This concern might have been raised by the basic hermeneutic instability put into place by, among other things, the fifteenth-century clothing in this image. As I said earlier in this essay, the green shoe is an addition unique to fr. 2646's image of the Bal des Ardents, at least in terms of the descriptive details supplied within the text. It is the shoe's status as an addition, as a source of discrepancy between text and image, that makes it hermeneutically productive. It encourages the viewer to search for a reason why this shoe might be there (as I have been doing throughout this essay), and, in so searching, to be drawn into greater imaginative involvement with both text and image.

<39> The miniature of the Bal des Ardents is filled with elements that point beyond this manuscript, elements that call out to the viewer's personal experience or imaginative expansion, and, as a result, emphasizes the image's superior capacity to engage these different qualities. The figures in the foreground of the image have their backs turned to the viewer, their faces obscured (Figure 5); yet their bodies are still expressive, expressive enough, I think, to encourage the viewer to imagine facial expressions to accompany these poses. To find satisfactory expressions, the viewer could rifle through his own memories, of other times he witnessed some terrifying event or saw someone else reacting to such an event. On the left side of this image, one of the burning men staggers off to the side, heading (it seems) through the curtain being held back by an attendant (Figure 6). Beyond this curtain, blackness, uncertainty, the question of where he is going and whether or not he will survive. Now, as the reader continues through the text, he could probably assume that this figure represents the son of the lord of Nantouillet, who is able to put out his flaming costume by immersing himself in a tub of water in an adjoining room. However, in the image's moment of suspense, this blackness seems like pure potential, encouraging the viewer to imagine all kinds of spaces beyond the curtain, even to recall or to imagine himself moving through a castle and peering into the darkness behind curtains.

<40> Thinking about these expansive details, I am reminded of Alfred Acres's concept of "elsewhere," developed in the context of fifteenth-century panel paintings. Acres labeled as "elsewhere" those aspects of fifteenth-century panel which "[demand] a different brand of attention - demands it, and at the same time reroutes it towards something we cannot see" (23). These are the passages deep in the background of Flemish paintings that seem to point to a world extending far beyond the boundaries of the panel. Acres offers as an example the two small men looking over a bridge in the background of van Eyck's Rolin Madonna (Figure 7):

The man on the left leans forward to consider what lies below … It is not his outward gaze that matters but his decidedly downward one, which surveys a vista that no one else will ever behold. His privileged looking is brought further into relief by his companion, who, like us, can only imagine a view he is denied. (Acres 24)

These "vistas," according to Acres, are never directly represented, but more hinted at, by the far-away distances and obscured-yet-attentive figures included in these paintings.

<41> Acres argues that these "elsewheres" aren't secondary details - not mere staffage that distracts from the real subject matter of the painting in the foreground - but are instead a way of "painting things not seen … they gesture towards the painter's power to reach beyond the scope of the eyes and there to demand space … in the imagination" (32-33). This understanding of painterly "realism" goes beyond the careful rendering of anecdotal details. Instead these details lead the viewer into an endlessly proliferating series of associations, drawing on empirical experience. I think these obscured faces, these shadowy backgrounds in fr. 2646's image of the Bal des Ardents offer the same opportunity for imaginative expansion, a way to evoke and implicate the viewer's reality without having to represent this reality directly or completely.

<42> However the past's increased dynamism, its links to the fifteenth-century reader's living experience, also suggests that the interpretation of this past has itself become dynamic, its meaning potentially changing with successive readings. In an object designed to establish a particular patron's demonstrative control over the meaning of the past, this instability could be dangerous. For example, it could assist in the gradual elision or suppression of the patron's creative prominence, buried under the sedimentation of hermeneutically equivalent readings. Or, even worse, Louis of Gruuthuse might himself be prey to future manipulation, subject later to the same re-interpretations and recontextualizations that he has enforced on the fourteenth-century past.

<43> It is in the face of this continually developing meaning that historically specific costume restates a particular class of viewer control over the meaning of that past, and gives the fifteenth-century viewer of this manuscript a visual touchstone to provide them a quantum of hermeneutic confidence. The images in fr. 2646 do not provide a single correct meaning, but instead offer a different, perhaps even two-fold interpretive experience: on the one hand, these images, in their anecdotal richness, direct the reader to rework the meaning of the text to suit his own interpretive needs, to revisit the text and to work out new meanings in the space provided by the images' representative excess; on the other hand, these images specify a temporal limit to this interpretive expansion, a limit visualized in the very specific details that offer to only some readers the possibility of continual interpretive engagement. Louis of Gruuthuse is offered a place in this manuscript, in a visual world in which he is a full and familiar participant; other readers in other, more distant times, are not offered similar hermeneutic purchase. The fifteenth-century reader's understanding of the past might change, but interpretive priority is nevertheless afforded to this meaning. Français 2646's demonstrative historical specificity exercises an anxious control against the interpretive incursions of future readers and future readings.

Gonna Dress You Up in My Angst

<44> Yet, as I use the phrase "anxious control," I feel as if a fissure opens up in this essay, another kind of instability in addition to those I see lurking behind the historically specific pageantry of fr. 2646. I say that Louis of Gruuthuse's control is anxious - but why? After reading an earlier draft of this essay, one reader asked me: what are the stakes of the word "anxious" here?

<45> There is something instinctive and sympathetic in my use of this word anxious, as this word came to mind to describe the operations or manipulations occurring in this manuscript before I had a sense of what "anxiety" could mean as a term with its own critical history. But, as I read more about this term, it seemed like many of its aspects certainly seemed to match up with the model I've created for fr. 2646. For example, Sianne Ngai has pointed to anxiety's "special temporality: the future-orientedness that makes it belong to Ernst Block's category of 'expectation emotions" (209). Anxiety is an emotion that is primarily anticipatory, looking for something to happen in the future and to control, preemptively, how that thing might happen (Ngai 209). This attempt to shape and configure the world, to prevent a threat that is foreseen rather than actual, does seem to match the hermeneutic dynamic that I have just attributed to the images in fr. 2646.

<46> Moreover, this "anxious" attitude towards the future, this desire for a present use of the past to control the future, has been identified as a characteristic facet of medieval historiography. Gabrielle Spiegel has characterized medieval historical practice as "prophetic," "not in the Old Testament sense of decrying contemporary practice and foretelling better or worse days to come, but in its ability to establish genuine historical relationships between temporally distinct phenomena" (93) The relationship between present and past was "prophetic" because it justified present actions, and thus offered people in the medieval present a sense of control, a history that "described a political future that would unfold as the realization of the potentialities of the past and thus implicitly legitimized … political programs and policies … For in such a scheme the past was prophetic, determining the shape and the interpretation of what was to come" (Spiegel 93). The future is no longer potential and uncertain, but instead a controlled outcome. Thus, at least in a medieval context, a relationship to the future, an attempt to determine and predict the future, is tangled up with the attempt to impose a particular present significance on the past.

<47> Something about this seems all too convenient. I cannot ignore that the same anxious fixation on the threat that the future might pose to one's interpretive primacy describes not only Louis of Gruuthuse's possible engagement with his copy of Froissart's Chroniques, but also my own engagement with this manuscript and the fraught anticipation leading up to this engagement. Perhaps this is where the methodological stakes of word "anxiety" are suddenly raised. While the explanation I have offered for fr. 2646's seeming resistance to future interpretations has a certain amount of historical reasoning behind it, the word anxiety suggests that this reasoning is built on deeply ahistorical foundations. It is built on the sympathy between myself and the imagined Louis of Gruuthuse, on an anxiety that we share across centuries, mediated by fr. 2646. Any such sympathy might be historically suspicious, but a sympathetic "anxiety" is particularly so: anxiety is often described as having a projective structure. Ngai explains the projective character of anxiety: "in psychological discourse, for example, anxiety is evoked not only as an affective response to an anticipated or projected event, but also as something 'projected' onto others in the sense of an outward propulsion or displacement - that is, as a quality or feeling the subject refuses to recognize in himself and attempts to locate in another person or thing" (210).

<48> This does feel like what happened when I looked at fr. 2646, and as I write and think about it now: "anxiety" seems to hover in between myself and the object, and by extension Louis of Gruuthuse. Wherever it comes from, anxiety seems to seep out and render everything anxious, and, in the end, make meaning into something that is inevitably idiosyncratic and insular. Perhaps the evocation of "anxiety" in this essay suggests that I have formed, to borrow Carolyn Dinshaw's phrasing, an "amateur" relationship to the past, one that is "not dictated by a mystified scientific method that requires not only a closed system and the elimination of chance but also, and most fundamentally, the separation of subject from object. In fact, not 'scientific' detachment but constant attachment to the object of attention characterizes amateurism" (22).

<49> But this "projective," "amateur" relationship might also not be a completely accurate description of what happened when I saw fr, 2646, and what's happening now. This apparent attachment might be its own form of avoidance. Ngai points to a "spatial" character in anxiety: "accounts of anxious subjectivity … depict anxiety less as an inner reality which can be subsequently externalized than as a structural effect of spatialization in general" (212). Rather than the anxious subject "projecting" out to create a pathological attachment with the object of that anxiety, anxiety instead emerges as the subject tries to create distance with such object, to reaffirm a distinction between a subject "here" that is anxious and an over-there that causes this anxiety. In this case, anxiety is not really something to be cured or resolved, but rather a of way maintaining a self-preserving, often codedly "masculine" distance from sites of perceived nothingness or indeterminancy: "there is a form of "revolutionary uplift' which anxiety's projective character makes available to these intellectual subjects and which directs attention away from questions of 'sinking' worlds, 'horrible interspace[s]," and "unknown, foreign feminineness[es]' as quickly as it raises them, such that this moody organization might be described as an aversive turn from the very occasions of the subject's aversion" (Ngai 247).

<50> Perhaps it is such proud aversion that underlies the anxiety that emerges when I think about fr. 2646. This essay is marked by extensive hesitation: if I have avoided one kind of historical interpretation (which would uncover a specific meaning within the images in fr. 2646), it is largely out of an anxiety about the tenability of such an interpretation. Perhaps I am anxious that I am inadequately prepared, or not perceptive enough to be able to come up with some historical explanation for fr. 2646 that is both sufficiently convincing, and also sufficiently novel to attract positive disciplinary attention. I may not have been innovative enough. While much of this essay has been devoted to coming up with justifications for why such a specific meaning such as that offered by Olivier Ellena in an earlier citation [18] might be unnecessary, it has done so only to offer a slightly different, but equally historical interpretation for the images in fr. 2646: these images prevent me from accessing their meaning by design. So, anxiety here becomes a way to distance my own work from more apparently conventional historical interpretation, a flare sent up to alert my readers to my more complex and hermeneutically fraught self-awareness.

<51> Perhaps I am anxious because fr. 2646 asks too much, or asks too little - in either case, it seems like it could do without it me, not in need of any further interpretation. Understood in this way, my anxiety is, again, not a result of a sympathy with or attachment to someone in the past. Instead it is an aggressive affirmation of my own subjectivity against fr. 2646's oceanic calm, a flight away from a sublime multitude of interpretive possibilities. This perhaps explains why Acres's concept of "elsewhere" appealed to me as I thought about this manuscript - it attempts to contain and spatialize this fluidity, to a create a space from which I project/protect myself as I imagine the anxious motivations guiding this manuscript.

<52> When I use the word "anxiety" to describe fr. 2646, to describe the motivations behind the creation of this manuscript and thus identify it as the source of my allegedly sympathetic "anxious" response, I am referring to an interlocking series of uncertainties: an uncertainty where anxiety is actually emerging, when it is actually emerging, and who is responsible for feeling anxious. I can fill up the "elsewheres" in this miniature, but, due the substance and nature of what they are filled with, interpretive satisfaction remains elusive. On the one hand, I can imagine that I have a strong sympathy with an equally anxious Louis of Gruuthuse, a direct channel of communication opened with the past; on the other hand, anxiety marks this meaning as unavoidably and irredeemably particular, as it reinforces the overwhelming control exerted by my own anxious subjectivity. With this idiosyncratic approach to historical meaning, I cannot avoid the feeling that, regardless of how strong my connection with this manuscript might seem, it is only a fleeting one, one of the many that will emerge throughout this object's continued existence. My interaction with fr. 2646 is continually haunted by the specter of the future, of the anxious sense that its true meaning is always elsewhere.

Figures

Figure 1: Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscrit français 2646, folio 176, c. 1475 © Bibliothèque nationale de France. (Source: gallica.bnf.fr)

Figure 2: The Bal des Ardents, Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscrit français2646, folio 176, c. 1475 © Bibliothèque nationale de France. (Source: gallica.bnf.fr)

Figure 3: Detail of green shoe, Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscrit français 2646, f. 176. © Bibliothèque nationale de France. (Source: gallica.bnf.fr)

Figure 4: Detail of woman wearing green shoe, Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscrit français 2646, f. 176 © Bibliothèque nationale de France. (Source: gallica.bnf.fr)

Figure 5: Detail of two men standing in foreground, Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscrit français 2646, f. 176 © Bibliothèque nationale de France. (Source: gallica.bnf.fr)

Figure 6:

Detail of curtain being pulled back, Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscrit français 2646, f. 176 © Bibliothèque nationale de

France. (Source: gallica.bnf.fr)

Figure 7: Detail of background from Jan van Eyck, Rolin Madonna, c. 1435, oil on panel, Musée du Louvre © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski. (Source: photo.rmn.fr)

Notes

[1] This article is drawn from my dissertation, "'The Remembrance of Good Men and the Stories of the Deeds of Valiant Men Justly Inflames and Excites the Hearts of Young Knights': Representing History in the Fifteenth Century," which stages a series of encounters between fifteenth-century Flemish illuminated manuscripts, twenty-first-century historians, and critical theories of affect and affectively-informed historiography. Some of the material in this article was presented at the 2013 International Congress on Medieval Studies. I want to thank Prof. Jonathan J.G. Alexander, Prof. Kathryn Smith, and Prof. Jonathan Hay, who, as dissertation readers, gave invaluable feedback on the earlier version of this chapter in my dissertation; I also want to thank Joseph Ackley, Lauren Cannady, Rachel Federman, Cindy Kang, Abby Kornfeld, Marci Kwon, Elizabeth Monti, Christina Rosenberger, and Shannon Wearing, who were all kind enough to read at least one iteration of this material.

[2] Louis of Gruuthuse (also know as Louis of Bruges, particularly in French scholarship) lived from 1427 to 1492, and was throughout his life (or, at least until the death of Mary of Burgundy in 1482) a prominent member of the Burgundian nobility. The standard work on the life of Louis of Gruuthuse is van Praet.

[3] Volume 4, Chapter 32 in Buchon's edition.

[4] "a grand'peine et martire," Froissart 4: 178; ch. 32. All English citations from Froissart are my own translations from the original French. I will include the original French in an endnote.

[5] These include Winkler 75, 98, 192; Stock; Ellena; Kren and Scot McKendrick; Hans-Collas and Schandel.

[6] In the original French, "L'illustation du livre IV des Chroniques de Froissart: Les rapports entre texte et image." Again, all English translations are my own, and I will include the original French in an endnote.

[7] "où s'épanouit une esthétique 'macabre' qui est celle du XVe siècle." Harf-Lancner and Le Guay 102.

[8] "le peintre du [fr. 2646] rend particulièrement justice à l'intensité dramatique du récit de Froissart. Tout est désordre, agitation et confusion dans cette scène aux teintes sombres éclairée par les seules grandes taches rouges des tentures, ici inséparable du thème du feu." Harf-Lancner and Le Guay 105.

[9] "Le manuscrit [fr. 2646] se distingue aisément des autres par la force et la violence de l'image." Harf-Lancner and Le Guay 105.

[10] This distrust of reproduction is widespread within the discipline of art history, but for a discussion of this issue in the context of illuminated manuscripts see Camille, and Herman.

[11] "il fit pourvoir six cottes de toile … et porter et semer sus delié lin, et les cottes couvertes de delié lin en forme et couleur de cheveux." Froissart 4: 177; ch. 32.

[12] For general information about the style of dress in the late fifteenth century, see Scott, and Van Buren 208.

[13] "ainsi, les événements du XIVe siècles rapportés par Froissart, traduits en images dans les années 1470-5, servent de fondement historique aux bouleversements sociaux qui, à la fin du Moyen Age, font définitivement perdre à la classe nobiliaire son immunité. Au moment où le gouvernement de Charles le Téméraire proclame que la justice est la 'chose principale' et où il pratique la contrainte par peur, Louis de Gruuthuse, acteur et spectateur du milieu curial, cherche les sources de cette violence dans les exemples fournis par Froissart." Translation is my own. Ellena 68.

[14] See, for example, Judith Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

[15] See <21>

[16] For the most recent study of patterns of manuscript consumption during the rule of the Burgundian dukes, see Wijsman.

[17] In Wijsman and Jolivet, the authors draw an even closer connection between "fashion" and manuscripts in the Burgundian court, suggesting "in the emergence of identity at the court of Burgundy between the 1430s and the 1450s, dress played a major role, but in 1442 the series of changes in fashion of clothing that had characterised the 1430s came to a standstill and it was from this moment that the taste for specific texts and illuminated manuscripts emerged. Fashion in literary and bibliophile taste replaced, so to speak, fashion in dress" (285).

[18] See <23>.

Works Cited

Acres, Alfred. "Elsewhere in Early Netherlandish Painting." In: Hamburger, J.F. and A. Kortweg (eds.). Tributes in Honor of James Marrow: Studies in Painting and Manuscript Illumination of the Late Middle Ages and Northern Renaissance. London: Harvey Miller, 2006: 23-33.

Belorzerskaya, Marina. Rethinking the Renaissance: Burgundian Arts across Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Camille, Michael. "The 'Très Riches Heures': An Illuminated Manuscript in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." In: Critical Inquiry 17.1 (Autumn 1990): 72-107.

Dinshaw, Carolyn. How Soon is Now? Medieval Texts, Amateur Readers, and the Queerness of Time. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Ellena, Olivier. "La noblesse face à la violence: arrestations, exécutions et assassinats dans les Chroniques de Jean Froissart commandés par Louis de Gruuthuse (Paris, B.N.F., mss fr. 2643-46)." In: DuBruck, Edelgard E. and Yael Even (eds.). Fifteenth Century Studies 27: A Special Issue on Violence in Fifteenth-century Text and Image. London: Camden House, 2002: 68-92.

Froissart, Jean. Chroniques. Ed. J. A. C. Buchon. 4 vols. Paris: A. Desrez, 1835.

Hans-Collas, Ilona and Pascal Schandel (eds.). Manuscrits enlumines des anciens Pays-Bas m éridionaux, Vol 1: Manuscrits de Louis de Bruges. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 2009.

Halberstam, Judith. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

Harf-Lancner, Laurence and Marie-Laetitia Le Guay. "L'illustation du livre IV des Chroniques de Froissart: Les rapports entre texte et image." In: Le Moyen Age 96 (1990): 93-112.

Hedeman, Anne D. "Presenting the Past: Visual Translation in Thirteenth- to Fifteenth-Century France." In: Morrison, Elizabeth and Anne D. Hedeman (eds.). Imagining the Past in France: History in Manuscript Painting, 1250-1500. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010: 69-88.

Herman, Nicholas. "The Illuminated Manuscript in the Age of Digital Reproduction: Beyond Benjamin and 'contra' Camille?" In: The Challenge of the Object: 33rd Congress of the International Committee of the History of Art, Nuremberg, 15th-20th, July 2012. Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalemuseums 2013: 599-602.

Kren, Thomas and Scot McKendrick (eds.). Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003.

Scott, Margaret L. History of Dress: Late Gothic Europe, 1400-1500. London: Mills & Boon, 1980.

---. "The Role of Dress in the Image of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy." In: Morrison, Elizabeth and Thomas Kren (eds.). Flemish Manuscript Painting in Context: Recent Research. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum 2006: 43-58.

Spiegel, Gabrielle. "Political Utility in Medieval Historiography: A Sketch." In: The Past as Text: Theory and Practice of Medieval Historiography . Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1997: 83-98.

Stock, Lorraine Kochanske. "Froissart's Chroniques and Its Illustrators: Historicity and Ficticity in the Verbal and Visual Imaging of Charles VI's Bal des Ardents." In: Studies in Iconography 21 (2000): 123-180.

Van Buren, Anne H. with the assistance of Roger S. Wieck. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands, 1325-1515 . New York: The Morgan Library & Museum, 2011.

van Praet, Joseph. Recherches sur Louis de Bruges, seigneur de la Gruthuyse; suivies de la notice des manuscrits qui lui ont appartenu, et dont la plus grande partie se conserve à la Biblioth èque du roi . Paris: De Bure frères, 1831.

Wijsman, Hanno. Luxury Bound: Illustrated Manuscript Production and Noble and Princely Book Ownership in the Burgundian Netherlands (1400-1500). Turnhout: Brepols, 2010.

Wijsman, Hanno and Sophie Jolivet. "Dress and Illuminated Manuscripts at the Burgundian Court: Complementary Sources and Fashions (1430-1455)." In: Blockmans, Wim (ed.). Staging the Court Burgundy: Proceedings of the Conference "The Splendor of Burgundy." Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2013: 279-286.

Winkler, Friedrich. Die Flämische Buchmalerei des XV. und XVI. Jahrhunderts: Kunstler und Werke von den Br üdern van Eyck bis zu Simon Bening. Leipzig: E.A. Seeman, 1925.

Return to Top»