Reconstruction Vol. 15, No. 1

Return to Contents»

Living in the Future Anterior: Trauma and Autobiography in the Work of Vincent Chevalier and Francisco-Fernando Granados / Ricky Varghese

<1> What might be considered a now famous image in the long history and tradition of Western philosophical thought and the study of aesthetics sets the stage for the discussion to follow. The image being invoked here is that for which philosopher Walter Benjamin attempted to offer an ekphrasis. In his posthumously published Theses on the Philosophy of History, Benjamin offers a description to Paul Klee's painting Angelus Novus; his description is suggestive of the thematics of temporal dispossession and repossession, which will form the foundation for the analysis forged here. Benjamin described the angel of history, Klee's Angelus Novus, as such, first by quoting his friend and contemporary Gershom Scholem:

My wing is ready for flight,

I would like to turn back.

If I stayed timeless time,

I would have little luck.

- Gershom Scholem, "Greetings from Angelus"

A Klee painting named "Angelus Novus" shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.[1]1

The image, in an obvious sense perhaps, describes a rebarbative struggle against notions of linear temporality and historicity and, as well, a stuckness, a temporal stuckness within which the angel appears to be laid stagnant, imprisoned, encased, petrified, entombed even. He recedes into a future, ever being pulled facing backward into that futurity, while simultaneously he cannot help but still fixedly position his attentive look upon the historical catastrophes of the past, being piled in front of his feet so to speak, like much historical wreckage, waste, debris, and detritus. In a way, this emblematically stages the surreptitious simultaneity of both (and the push-and-pull struggle between) remembrance and forgetting. Furthermore, it shows how the flow of time and temporality works to endure both the dying of the past and the coming of the future in the same instance, and how this instance, the present instance, radically enervates both that past vis-à-vis memory, remembrance, and commemoration, while giving way to a futurity that cannot be and refuses to be delimited or even abnegated. It is in the look back of the angel, as described by Benjamin, that we might begin to regard how one may possibly relate to the demands of both temporality and historicity, particularly under the hubristic presumption that time is always already linear; that it moves, as though unchallenged, in a straight line, assuming beginnings, middles, and endings.

<2> What the look then signifies is an annulment of this presumed linearity; a rupture, a caesura in time, wherein this look forges a bridge between the past and the future, wherein the past cannot help but inform life in the future, wherein the future is mired by the haunting presence of the past always already hovering, lingering overhead. All futurity, in such a scene, is foundationally connected to the remembrance of the past, while all remembrances of lost time, all searches for the past, always already come to anticipate an uncertain future, whose only certainty is that it is always in a state of ever-arriving. The scopic nature of this tedious relationship between the past and the future - the look back of the angel at the past as it is propelled, apparently furiously, by the storm called progress into the future - cannot be ignored. This scopic fidelity - to the past and how it is remembered, how it is sutured up against how the future is approached and approaches the one who remembers - regards time as anything but linear. It assumes that linear time can be ruptured specifically at how one looks, precisely in the look itself, at the past, and how that look informs both what is remembered and what is otherwise forgotten (or forgotten as otherwise). This look thus straddles the fine line between memory and forgetting.

<3> In 1959, nearly twenty years after Benjamin penned his Theses, Marguerite Duras, as though invoking the Benjaminian realization concerning the angel's look, in her screenplay for what would become Alain Resnais's classic tale of memory, forgetting, and the seeming obduracy of impossible love at the site of a disaster, Hiroshima mon amour, would write the lines "forgetting will begin with our eyes" [2]2 - lines uttered in the film by the French woman, one of the two central characters in this tale; lines that account for both the obstinate insistence of memory and the stubbornness with which forgetting, repression as such, persists.

<4> The tale is about thwarted and impossible love, on an impossible terrain - Hiroshima - impossible precisely because it might be difficult, as such, to imagine a love blossom in the span of a day and a night, which is the span of the film's narrative, upon a terrain affected by unimaginable historical trauma. The lines uttered by the French woman are attuned to both the weight of history and the destabilizing nature of memory, its near untenable, unbearable, and fragile nature. It also wrestles, like the angel, with temporality. In those lines, forgetting is marked by its nod toward futurity, it will be an event of the future, and it will be anticipated; it exists as such, as anticipation itself. But, the forgetting of what? Again, temporality becomes the object of a turgid struggle. Here, the forgetting is that of the past as recited by the French woman to her nighttime paramour who she meets during her stay in Hiroshima, the Japanese man.

<5> At precisely the moment when a narrative as this could become predictably cliché - predictable because of the apparent predictability of what a tale about forbidden love might promise as far as a narrative arc mired by futility is concerned - Hiroshima mon amour veers away from being just another story about fated star-crossed lovers and their tragic story of an impossible love on an impossible landscape. It, in fact, uses this impossibility to stage a "drama of vision,"[3]3 as Kaja Silverman suggested in her brilliant study of the film, wherein the French woman's relationship to Hiroshima and the Japanese man is only made possible as such due to her past; that this presence of an impossible love as it happens in the span of a nighttime tryst on an impossible landscape could only be made possible due to and owes itself to another impossible love that belongs to the past of the French woman.

<6> Fourteen years prior to her arrival in Hiroshima, she was a young girl of eighteen who grew up, amidst the war, in a small (fictional) town in France called Nevers. In her youth, she found herself in love with a German soldier - "my dead lover is an enemy of France," she would recount to the Japanese man as she tells him the story of her earlier impossible love that which made their own impossible love possible in the present hour, on the eve of her departure from Hiroshima - a now dead lover who would ask her to marry him as the war was coming to an end. Then, on the eve of their departure from Nevers, when she was to return with her lover to his home in Bavaria, while he was waiting for her by the banks of the river Loire, he is killed by one of her townsfolk, and she finds his dying body there. She remains with the body, lying atop it - she lies atop it not wanting to leave the body of her dead lover unattended, as though like an Antigone who claims the ethical through her desire to place soil atop and thus bury her brother Polynices despite and perhaps in spite of Creon's rigid order - as it loses both heat and life, turning into corpse under her very own body, until the very next day when it is removed. What follows is a yearlong period of mourning, where, as though in the form of a descent into madness, all she sees is him and her love for him. In a way, as Duras describes her, one might consider her a woman "more in love with love itself"[4] 4. It is this that she is afraid of forgetting, that the moment she stops "seeing," being witness to, her erstwhile lover and her past, him and it would both cease to exist; they would vanish; they would be forgotten, banished outside of her memory. The subject, here, becomes dispossessed of her own past, but this dispossession of the past will be an event that occurs in the future, that will only ever be felt in its anticipation as "beginning with [her] eyes." However, the subject, the French woman, also stages a dramatic repossession of her past, as in the form of a witnessing, vis-à-vis the future in which she will recover this past in its telling, through her telling "[their] story…[It] was…a story that could be told"[5]5 to the Japanese man.

<7> To return and reiterate this aforementioned point, if as Duras proposed, "forgetting will begin with our eyes," this paper attempts to explore this scopic fidelity - which is the angel's fidelity toward the act of bearing witness - tied to how we choose to remember, forget, and live with the past in the present. To do so, I offer a reading of the work of two Canadian artists, namely Vincent Chevalier and Francisco-Fernando Granados, whose respective aesthetic practice compellingly speak to and mobilize what I come to consider as a sort of temporal dispossession, a displacement not merely spatial in its parameters, but more so temporal, to then enact a repossession of some particular aspect of their past to which their respective works are always already addressed. My intention is to explore what it might mean to live, as though unconsciously, in a time, as signified by their respective works under examination here, in a future, that has already come to pass, that was already named as (and in) the past. Furthermore, I explore what it might mean to think the future anterior - the future past of the events of both forgetting and remembering - as a moment of such a temporal dispossession in which a redemptive politics, a repossession of time itself, might be possible within and through aesthetic practice. It is my assertion then that this might offer up new ways of thinking the autobiographical as anticipatory of witnessing trauma and as unorthodox precisely for this reason. What remains - to be looked upon and remembered of oneself - becomes the central question here, as envisioned by the work of both these artists, the former referencing life under the sign of HIV and the latter referencing the life of a refugee. But first, let me tarry a little alongside with this notion of temporal dispossession and its simultaneous repossession, or retrieval, in the scene of being a witness to oneself and one's relationship to one's own time.

A Scene of Temporal Dispossession and A Scene of Unbearable Retrieval

<8> Poet Anne Michaels, in a dialogue with writer John Berger, published under the heading Railtracks, spoke of dispossession in the following terms: "It is the exile's prerogative to personalize history. To personalize history is the prerogative of the dispossessed, it is the one right given to us in our dispossession."[6]6 Here, the dispossession of the exile, the banished, or as will be described later in the case of the figure of the refugee in the work of Granados is, strictly speaking, marked by a disruption in how one relates to one's own spatial parameters. Evicted from one's homeland, from one's own solemn piece of earth, from a room with one's own view, the dispossessed has only to turn to history, has only history to turn to, to make this - her or his - history intimately personal, to remember and bear witness to the scene of that dispossession as part of one's personal possession of oneself, as a coming to terms with and a shoring up of one's most intimate losses. What, then, would it mean to move the scene of this dispossession from its spatial parameters to address the scene of temporality perceived and presumed to be linear? Put in another manner, what, then, would it mean to dispossess dispossession of its spatiality and have it respond to the demands, ethico-political in tenor, of temporality? More simply construed, what does the subject's dispossession of and in time look like? What would it mean for the subject to experience dispossession as temporal, to feel dispossessed of one's sense of time, one's own time?

<9> A moment in philosopher Rebecca Comay's elaborately architected and nuanced study of historicity and trauma - at the interstices of what appears to be simultaneously both a scene of threateningly grave political upheaval and a much-hoped-for revolution - Mourning Sickness: Hegel and the French Revolution, might provide an avenue worth exploring when considering these abovementioned concerns regarding temporal dispossession. There, in a lucidly crafted passage concerning trauma and its description, she articulates this trauma as "[marking] a caesura in which the linear order of time is thrown out of sequence"[7]7. Brilliant in its descriptive simplicity, Comay situates and cites trauma within the auspices of a linear notion of time being dealt with a cut, a slicing cut that appears as an unreal, perhaps all-too-real, abstraction, because how else can an object such as time - if it is an object at all, perhaps a mere object of keeping score of what can be remembered and what might be forgotten and for the purposes of their respective analyses - be slashed open, or be forced to bear the brunt of being put asunder, except through the manner of an abstraction? What comes after this definitional instance is even more evocative of what I have proposed as a dispossession implicit within the experience of temporality marked and marred by trauma or the traumatic, as such. Comay goes on to suggest that "we compound this temporal disorientation every time we try to quarantine trauma by displacing it to a buried past or a distant future"[8]8. While her turn of phrase "disorientation" finds itself and remains within the register of spatial parameters - the subject becomes disoriented, directionless, pulled toward the future; her/his look, like the angel's, gapes at the past - what comes in the form of yet another imperative would be to think of the subject as situated in a state of dispossession precisely in relation to how s/he experiences time; the thrown-out-of-sequence nature by which she/he cannot make sense of her/his own temporality, except as a byproduct of or as an aftermath to the traumatic cut.

<10> In a way, this scene, as marshaled by Comay, performs rather efficaciously the dispossession and repossession of temporality as shown in Benjamin's description of the angel of history. Here, it becomes useful to reflect on the word "quarantine" as it directly addresses the moment of trauma, precisely because it forces a deferral of the experience of traumatized time itself to some other time, an other time now repositioned, reinstated into, and repossessed within the scene of a now long-departed past or a future as yet to arrive or imminently anticipated, felt as anticipation itself, in our experience of it. Traumatized time, or the time of the cut, or the rupture that flays open the skin of linear notions of historicity becomes strikingly marked by its own weighty unbearability. What is quarantined is not merely memory itself in the general sense, but the particular memory of the cut, the trauma itself; it becomes an abstract experience of abstraction itself, an abstraction of the time of the cut relinquished and released from the stranglehold of presumptions that deem time as linear. Later in her text, Comay describes abstraction as "the deadly capacity to cut into the continuum of being and bring existence to the point of unreality"[9]9 . Abstraction, in this instance, becomes a way to contend with the unreality, the unbearably all-to-real nature of the cut itself in time wherein time is equated to the continuum of being. The unbearability of this cut can only be felt in the manner of such an abstraction, an abstraction of how time is retrieved vis-à-vis through its memory, a memory of both the past and the future to which it is fervently attuned to and directed at.

<11> The angel cannot help but be pulled, facing back into the future, in the name of both progress and seemingly unbounded progression. However, as though by way of its own superego, it severely castigates itself for being pulled into the future by resisting, nay refusing, to look forward, and furthermore by priming its attentive look onto the past that it attempts to reprieve, as though it is responding to an ethical demand to remember the past, to never forget the catastrophes borne out of history. This retrieval is done so as to ensure that the future might be always already informed by the past, such that it cannot exist outside of its own past, such that the past will always be the forebearer to its own futurity. The loss in and of time, as marked by the cut implied by trauma, is taken into account precisely as a future that has already come to pass, that has become "quarantined," as such, both in and from the past and, simultaneously both in and from the future as well. This loss in and of time can only be seen as redeemed, can only be seen as holding forth the possibility for the subject's or angel's redemption of its own past, if the future is already staged as a response to that past that has been lost, a past that in its own staging refers to and is directed at the future to come. It is in this scene, found in a future anterior time, that the angel seems to be tediously walking the tightrope between remembrance and forgetting. It is also here wherein we discover a retrieval of the past for life in the future - wherein the very retrieval of that past holds forth this very life as imagined in the future - as allowing for both the subject and the angel to bear witness to the existence of their own respective autobiographies, autobiographies that are redemptive of and for the past and the future alike. Such autobiographies break rules of convention regarding linear historicity. Such autobiographies, as well, become unorthodox precisely for this reason: that rules are broken regarding time, where the autobiographical arc is almost, if anything at all, profoundly self-aware of the ruptures embedded in its own narrative. Such autobiographies, as will be seen in my discussion of the work of both Vincent Chevalier and Francisco-Fernando Granados, are as much about the dispossession of time and one's complicated experience (the letting go) of it, as it is about attempting to understand the weight of the trauma (a holding onto the traumatic cut) that both artists are articulating their respective responses to - that of HIV as in the case of the former and that of the gesture of seeking refuge within the nation-state as in the case of the latter.

No Art After AIDS: On Vincent Chevalier and the Uncanny Time of Trauma

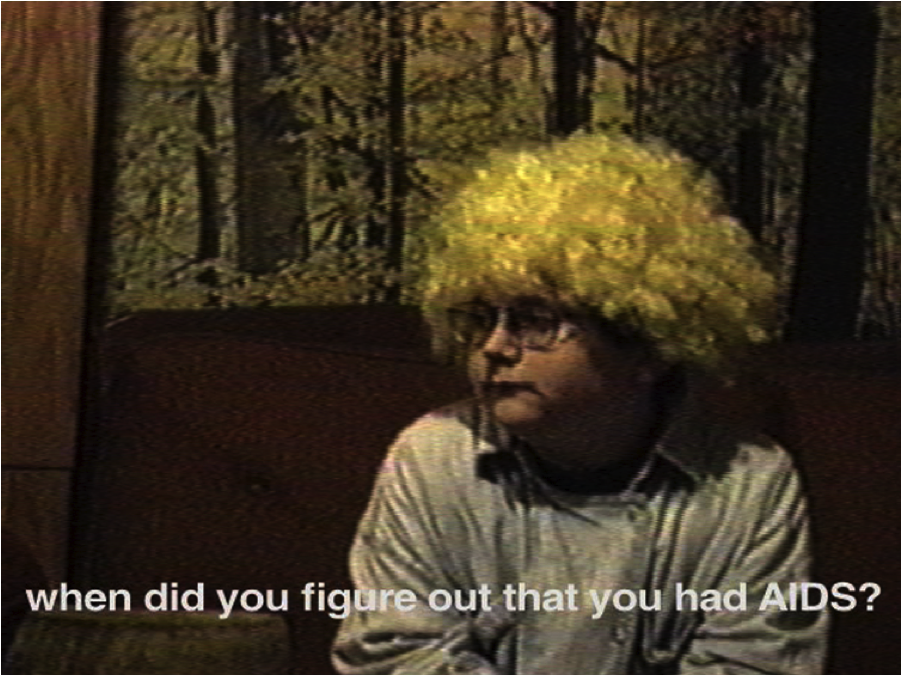

<12> The year is 1996 and a young, then thirteen year old Vincent Chevalier, donning an intensely bright blond wig, partakes in what appears to be an instance of child's play. His friends, sisters Chelsey and Kelsey Winchester, and he shoot a home video. This video theatrically stages what appears to be referential of a talk show format wherein, while Chelsey Winchester takes on the role behind the camera of the cameraperson, Kelsey Winchester performs the part of the talk show interviewer and Chevalier himself plays the role of the subject being interviewed, a man diagnosed with AIDS having contracted it from his wife. This performative instance of a home video, at once, both profoundly serious in retrospect considering its subject matter and, as well, a scene that is punctured by hilarity and the humorous intentionality of what appears as, as mentioned earlier, an instance of child's play becomes the object transformed later by Chevalier himself into a video art project.

Figure 1: So…when did you figure out that you had AIDS? (2010).

Still from video installation by Vincent Chevalier. Image courtesy of the artist.

<13> Six years after the home video was shot, at the age of nineteen, Chevalier himself tests positive for HIV. It will be still some years later, in 2010, when Chevalier having rediscovered the home video reformats it and organizes it in the manner of an art installation titled "So…when did you figure out that you had AIDS?" that resembles an autobiography, of sorts, of and for the future, of his own future in the making. In a manner of speaking, perhaps the first question the installation solicits a response for is that of how to contend with trauma when it was always already anticipated, felt as anticipation, in the past? Furthermore, how does one reside within such a history that was always already anticipatory of the weight and brunt of the historical trauma handed down by the AIDS crisis? Pushing this line of thought even further, what does it mean for the future when it was already preordained as an almost prescriptive futurity by the gesture of auto-inscription made in the past?

<14> It might be instructive for us to think through the suggestive "when" in the title of Chevalier's work. When "exactly" did he figure out that he had AIDS? The work situates its address within the realm of a desire to account for the temporal dispossession implicit in the asking of the question inaugurated by the signifier "when." In a way, the work itself is situated within the long drawn out history of queer male life and art under the sign of AIDS; a life and a history of art informed by the traumatic reverberations felt, upon both, by the AIDS crisis. Not quite unlike that famous dictum made by Theodor Adorno, in his 1951 essay "Cultural Criticism and Society," regarding the writing of lyric poetry after Auschwitz - "To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric" [10]10 - it would appear that Chevalier produces a similar commentary regarding the production of art in the face and time of AIDS, in the aftermath of AIDS as a scene of historical trauma. He does this precisely by positioning himself both as the subject of the installation and the object of the traumatic cut implied by the AIDS crisis itself in the presumed linear time of history. The work renders itself as both timely and timeless because it responds to the crisis in the manner of an auto-narrative that feels almost premonitory. It anticipates the future before it has happened; it regards time as always self-aware of the traumatic cut that is implicit within it. It also is an address - a look back - to the past that anticipated this future. It is a historiography in the form of a video that renders the past as having always already had the power to foretell the futurity that was just around this or that historical corner; a futurity that was always waiting on the sidelines to be inherited.

<15> It, as such, also provides a story regarding inheritance. Chevalier, in the restaging of such a scene of a premonition, a foretelling, arguably names his inheritance - AIDS and its aftermath - before it became a part of his own reality and lived experience. Living with AIDS was first rendered as an abstraction, an abstract experience, as in the form of a child's play in the making of the home video; then it became the all-too-real object of cultural inheritance that would be transformed into an object of art; an object of art that questions the very ways in which art itself might be mobilized as a response to a crisis. The future anteriority of the time in which the abstraction becomes the unreal, or perhaps the all-too-real, matter of personal historicity and aesthetic reproduction is the time in which AIDS will have become; in which it will have come to pass as an object to be inherited some time in the future, to be anticipated, to be remembered as a thing of both the past now long gone and the future that is always in a state of arrival, always yet to come, both timely and timeless. This time of the future anterior as deployed within the installation also situates the traumatic cut in temporality as dealt out by the AIDS crisis as an object both to be mourned as the past as in the form of the memory recorded within the video and to be melancholically remembered, held on to, simultaneously, as the coming to pass of the past in the future in the very realization, uncanny as it is, of the inheritance of the crisis itself by Chevalier, having tested positive years after the video was made.

<16> Time, and more specifically the time of AIDS as showcased in the work, becomes experienced here as both the past and the future that has now come to pass; it becomes both the object that is experienced vis-à-vis its dispossession in the making of the video as a personalized archive of memory in the past, and its simultaneous repossession in the video then being restaged years later to speak directly to the future that Chevalier has come to inherit. A case of Freud's uncanny arrives at its final resolution here - the time of AIDS, in the gesture of autobiography that Chevalier positions his video as, is uncanny precisely because it reveals itself to be "that species of the frightening that goes back to what was once well known and had long been familiar." [11]11 Much like the French woman, in Hiroshima mon amour, who anticipated her future encounter with her Japanese lover through her past encounter with her dead German lover, and whose future encounter with her Japanese lover comes to release her from the crypt of her own past, from the stranglehold the past had on her, Chevalier, through his piece, recognizes that AIDS - both as a historical metaphor for traumatic crisis and as lived experience - has belonged both to his past and to his future; it became the bridge between the two, making it, in a sense, both timely and timeless.

The Double Lives of Francisco-Fernando Granados

<17> In 2003 when a young Francisco-Fernando Granados at the age of eighteen, having only arrived in Canada as a refugee two years prior, allowed himself the opportunity to be interviewed by the Vancouver Sun for an article titled "Climbing Mount Canada." He did not presume that his narrative would be used for any other reason than the purpose of archiving his experiences of leaving his home in Guatemala and his experiences within, and as a member of, the new nation-state that he would henceforth be calling home. He did not presume, for instance, that he would be dispossessed of his own narrative in service of this new home. He did not presume, for instance, that nearly eight years later, he would discover the interview he did with the Vancouver Sun, now having been copied word-for-word, appropriated so to speak, into the form of a fill-in-the-blanks vocabulary exercise in an ESL textbook, titled Canadian Snapshots: Raising Issues, for adult newcomers to Canada. He was neither asked permission regarding the use of his past interview in this manner nor did he anticipate it as a possible textual byproduct of or aftermath to the interview.

<18> In the strictest sense that I have already suggested earlier regarding the subject of dispossession, here we find that dispossession as a scene of displacement and perhaps furthermore a scene of movement that not only occurs across parameters that can be understood as spatial - across the geopolitical (from Guatemala to Canada) as a subject seeking refugee status and across the textual (from an interview to an ESL exercise) as an object of study used for the purposes of linguistic training - but also occurs on lines that are profoundly temporal. A past, as in the scene of an interview that was conducted in the name of the nation-state, of propping up the nation-state, so to speak, was dispossessed of its affective capacity in a future wherein the now working and practicing performance artist Granados will have discovered his interview restaged as an object, an other object, outside of its original spatial and temporal context. The discovery of the past as other than to itself in the future marks the traumatic cut in any and all linear narratives that might work in favor of the nation-state and one's identification with it as either one seeking refuge within its seemingly protective confines or one seeking a sense of narrative and normative belonging under the presumption of it being a new piece of earth and home to call one's own. The disruptive and traumatic nature of this dispossession across both space and time cannot be ignored and would come to frame the basis on which Granados would formulate his performance work The Ballad of _______ B. But first, what does it mean to feel dispossessed of one's own narrative past? What would it mean, too, to recuperate that expropriated past of this narrative into a new scene - such as a performance piece as staged by Granados - as a response to the future into which that narrative past was otherwise appropriated, incorporated, and surreptitiously assimilated?

<19> Let us remind ourselves of what I mentioned earlier regarding Anne Michaels's impassioned comments regarding the experience of dispossession: "It is the exile's prerogative to personalize history. To personalize history is the prerogative of the dispossessed, it is the one right given to us in our dispossession." As such, to have left an erstwhile home in search of refuge and then to narrate the experience of that departure, to position that narrative within the scene of an interview as a story of a departure then to arrive in a new country is to attempt to personalize one's history, to attempt to personalize the history that one was dispossessed of by telling that story, reviving it in a new space and a new time outside of that dispossession. What took place, however, as can be seen in the gesture of the unpermitted appropriation of the interview into the scene of a vocabulary exercise in an ESL textbook, was yet another instance of the subject being dispossessed of his own narrative, dispossessed of both the space and time of that narrative. In a way, this repositioning of the interview in its appropriated form annulled that prior attempt made by the young Granados to personalize his history of displacement and dislocation via the interview itself. By displacing and thereby dislocating the narrative, Granados's interview was given a utilitarian value outside of its context of origin; the context of origin being the inscription and the telling of a story of migration and resettlement. The Ballad of _______ B is an attempt at repossessing the temporality of that interview; the work attempts to regard the interview outside of its transformation into a utilitarian object, which it became in its future; the future in which Granados would come to discover the vocabulary exercise.

<20> Performed for the first time, on April 26 2014, at Toronto's Harbourfront Centre, The Ballad of _______ B was part of a program curated for Hatch, a one-week residency for emerging artists producing live-action works that brought together the genres of performance art and theatre. The work, which is an hour long in duration, saw Granados "turning the stage into an action-based multimedia installation." [12]12 Three performers, namely Manolo Lugo, Maryam Taghavi, and Granados himself, took the stage, which they shared with an audience comprising of forty members. The audience was seated on two sets of twenty chairs, each set lined up alongside the front and back parts of the stage facing one another.

Figure 2: The Ballad of _____ B (2014). Installation shots; photograph by Manolo Lugo. Image courtesy of the artist.

<21> The performance took place in the middle parting on the stage between the two assembled sets of chairs, wherein the performers read out lines of a script that they each had on hand. The lines of the script were repeatedly recited, in the style of a lyric poem or a ballad as the title of the work would suggest, by each of the performers over the course of the performance. Structurally speaking, in the script, "the paragraphs are redistributed in the lyrical form referenced by the title with its quatrains of alternating eight- and six-syllable lines." [13]13 The script, which was simultaneously projected on to a screen directly above the stage to one side of it using an overhead projector, comprised wholly of lines from the fill-in-the-blanks vocabulary exercise that appeared in the ESL textbook; the very same exercise that was forged out of the interview Granados did with the Vancouver Sun. Arbitrary words, instantaneously and momentarily thought, were used by each of the performers to literally fill in the blanks as they each recited lines from the script.

FILL IN THE BLANKS:

_______ B's life is fraught with challenges.

In _______________

his family had a big house,

a nice car, and all three

boys had weekly allowances.

Now, he sleeps on the couch

while his two younger brothers and

parents sleep in the bed

rooms down the hall. But the clean-cut,

fresh-faced eighteen-year-old

is _____________________

about his life here. He

refers to ___________________

as his "hometown," proudly

thumping his chest. "I feel ___,"

he says. "It's ironic,

I know, because I'm not yet. I

just feel like I fit in

really well." When he was asked

how he had endured the

changes, the lack of ___________,

and the uncertainty

of his refugee status, he

says, "What I lived was so

___________________

-- the persecution -- that

coming here means going to bed

at night without having

a pyrotechnic bomb explode

on the roof of your house,

without cars following you and

people phoning in the

middle of the night. "I don't have

to worry whether my

dad will come home from work safe or

if he'll be _________.

Here I may not have a room or

an allowance but I

have peace of mind. That's the lesson -

___________________.

_______ B is so enthusiastic

about the youth group, he

attends Monday sessions at the

community centre

just for fun. "I don't want to diss

my hometown," he says," But

there isn't a whole lot to do

there at night."[14]14

Space and spacing become significant aspects of the performance. In one sense, the space and spacing in which the performance took place is a direct referent to the fill-in-the-blanks exercise that itself formed a part of Granados's performance. This space and spacing appeared to build on a particular sort of necessary didacticism that was evocative of and called upon the very didacticism of the exercise itself. The stage became both the space for enacting the piece, performing it as such, while also becoming the space in which the audience acted as both witness to the staging and partook in the performance itself in their role as witnesses to the work as it unfolded in front of them. The enforced collapse of the otherwise prescribed metaphorical wall between audience members and performers is suggestive of the collapse of the assumed wall between what it means to participate as both witness and participant simultaneously to scenes of historicity and trauma. The middle parting, the space, in which the performance took place, where the performers took their place on the stage came to signify the blank spaces in the exercise itself. Both the literal bodies of the performers and the arbitrary words they spoke in the gesture of filling in the blanks in the script they read aloud came to stand in for what filled in the spacing between the audience members assembled on either side of the performers. Both the use of arbitrary words by the performers to fill in the blanks of the textual exercise and the placing of the performance's audience members onto the stage, seated distinctively away from where they would otherwise ordinarily be found in relation to a standard theatrical production serve to act as re-inscriptions, re-inscriptions of both the seeming mundane nature of the exercise itself and the very ways by which the genre of theatre is expected to be conventionally staged, viewed, and received. Like the angel of history envisioned by Benjamin who bore witness to the catastrophes being piled like "wreckage upon wreckage…in front of his feet," the audience members, in this scene, bear witness not merely to the literal bodies of the performers moving about in the middle parting on the stage, but as well to the arbitrary words uttered and used to fill in the blanks of a narrative that can only be understood as displaced, dislocated, and dispossessed of its original narrator, the young Granados.

Figure 3: The Ballad of _____ B (2014). Installation shots; photograph by Manolo Lugo. Image courtesy of the artist.

<22> Granados's own description of the script he used for his piece, the fill-in-the-blanks exercise lifted from the textbook, offers a clarifying view of what the performance was supposed to both relay and achieve:

The Ballad of _____ B is a fill-in-the-blanks performance script based on the account of my life that appears in a 2003 Vancouver Sun article titled "Climbing Mount Canada." The tale told comes from an interview I gave to journalist Cori Howard when I was eighteen years old. I decided to work with the text as a rectified readymade after a dear friend of mine who teaches English as a Second Language to adults in Vancouver brought to my attention a passage from a vocabulary lesson in the textbook Canadian Snapshots: Raising Issues. I was shocked to see that the copyrighted text in the book was lifted word for word, without my knowledge or consent, from "Climbing Mount Canada." All identifying details from the article had been kept in the textbook: my name, age, country of origin, the place where I lived, and the name of a community space I used to frequent. In the lesson, the story is turned into a linguistic case study. I had been designated a "student" and given a letter before my name: "Student B: Francisco." Horrified and hurt by the violation of the appropriation, but also drawn by the feeling of self-estrangement caused by its perversity, I decided to work with the text. [15]15

By positioning the figural and grammatical blank to stand in for the very arbitrary nature by which a gesture at a personal narrative - an interview - can be assimilated into and thereby reduced to its utilitarian value as in the sense of being mobilized as an exercise in a language textbook, Granados forces the audience to linger, tarry about, around this arbitrariness in how identification is, at once, both made and destabilized after its formation through erasure. In both the continued and persistent repetition of the lines by the performers and the randomness with which each of them arbitrarily filled in the blanks in their recitation of the script, what is showcased is that the subject's personalized history, her/his memory of her/himself, becomes the object of an appropriated instance of self-estrangement, as Granados himself refers to it, where the subject continues to know himself as existing outside of the time and temporality of both the interview and its subsequent transformation into a language exercise years later. The self-estranged subject here is one that experiences this self-estrangement precisely through the dispossession of this narrative which was to otherwise offer him a sense of a linear notion of time and history in relation to the nation-state he was to call his new home - as it was presumed to manifest through his movement to and seeking of refuge in Canada. Rather, the text by being dispossessed of its original intent - the personalized account of oneself as given within the context of an interview - belongs to another time outside of itself, a time in which it would be discovered not as a personalized account but as a pedagogical tool restaged in the fashion of a language exercise for newcomers much like he himself was at one time.

<23> Wrenched out of its original and intended context, provided for by a young Granados, and then discovered by an older Granados, the traumatic cut experienced as estrangement in relation to the thrown-out-of-sequence of this narrative dispossession is precisely the subject of the narrative repossession staged by Granados in The Ballad of _______ B. By staging the work, Granados attempts to recuperate the lost time between the interview and its transformation into a language exercise. He can, however, only recuperate this lost time - between his youth and the time in the future when he will have discovered the violation of his narrative - in the form of a blank into which arbitrariness becomes repeatedly filled. Forgetting, as the French woman in Hiroshima mon amour suggested, will begin with our eyes, but perhaps remembering - both alongside and against the traumatic cut in time - as Granados seems to suggest might begin with attempting to see what remains, to see what the blank spaces can be filled in with, and to see what cannot be rendered easily to sight.

Toward a Theory of Temporal Dispossession

<24> While much has been written about the structure of spatial dispossession within such wide-ranging fields as Geography, History, Area Studies, Political Science, Anthropology, and Migration and Refugee Studies, from the brief exercise undertaken here, it appears that there exists an explicit need for a more detailed and rigorous exploration concerning the very character of the experience of loss as it pertains to the loss of time. Psychoanalysis has enabled this exploration, to some extent, in its rigorous application of personal historiography to understanding the traumatic gaps within one's narrative, specifically in how one remembers that narrative as it appears to move, seamlessly, from the past into the present and in relation to some sense of a future-to-come. Similarly, the philosophy of time and history, as exemplified by Benjamin through his metaphorical description of the angel of history and its temporal stuckness, has also served to further our understanding of the ways by which the temporal plays out in relation to the struggle between memory and its forgetting. All of this being said, it is still worth asking what, in the final analysis, the loss of time - one's structural, material, and psychical dispossession of it - means for the work of historiography or for historicity as such? What would it mean for the subject to regain a sense of her/his own time and personalized historicity? What would it mean also to inherit temporality?

<25> This final concern regarding the inheritance of temporality or the temporal is of particular interest precisely in light of what could be understood here, from the scenarios I have described, as not merely the inheritance of some or other linear notion of time, a time without breaks, halts, erasures, or ceasuras; rather, the time being inherited is one always already aware of itself being laden with ruptures and puncture wounds noticeable by those on the margins and sidelines of history. Any theory of temporal dispossession, as such, would have to imperatively take note of and account for the very ruptures in any presumption of time that speaks of it as a linear category. Such a theory would have to account, for instance, the way in which Chevalier, though playing at what appears to be a child's game of make-believe, was thrown-out-of-sequence nature of any sense of a linear narrative by precisely claiming the history of AIDS for himself years in advance of him contracting HIV or discovering his seropositive status. Such a theory would also have to account for the simultaneous affects of being drawn to and horrified by the experience of self-estrangement that Granados described when as an adult he discovered a personal text from his past, appropriated and re-packaged in service of the nation-state. In the case of both Chevalier and Granados, what might be recognized is a desire on the part of these artists both, at once, to critique the abstraction that the loss of an untenable object like time might be given over to and also to materialize this abstraction, the very abstract nature of time and its loss, into the scene of aesthetic production. The gestures, in both cases, regard the autobiographical as disjointed and unorthodox precisely because what is valued in both aesthetic scenarios is not a desire for a story that has a beginning, a middle, and an end in the form of a much sought-after need for closure; rather, what appears to be valued is the very desire to showcase their respective experiences with the dispossession of time; a dispossession that, in each case, makes any and all attempts at a linear autobiography impossible. Autobiographies, as such, are as much about what is known or remembered, culled from one's memory of one's remembered past, as it is about what is experienced as anticipation or as life having been lived already in a future anterior time where the past and the future seem to meet for the subject.

Notes

[1] Benjamin, Walter. 'Theses on the Philosophy of History,' in Hannah Arendt (ed.) Illuminations (New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1968), 257.

[2] Duras, Marguerite. Hiroshima, mon amour: A screenplay by Marguerite Duras (New York, NY: Grover Press, 1961), 80.

[3] Silverman, Kaja. 'The Cure by Love.' Public. No. 32, 2005, 41.

[4] Duras, Marguerite. Hiroshima, mon amour: A screenplay by Marguerite Duras (New York, NY: Grover Press, 1961), 111.

[5] Ibid., 73.

[6] Berger, John and Michaels, Anne. Railtracks (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, 2012), 47.

[7] Comay, Rebecca. Mourning Sickness: Hegel and the French Revolution (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), 25.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 77.

[10] Adorno, Theodor. Prisms (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1986), 34.

[11] Freud, Sigmund. The Uncanny (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 124.

[12] Granados, Francisco-Fernando. 'The Ballad of _______ B.' Canadian Theatre Review 162, Spring 2015.

[13] Ibid.

[14] The Ballad of _______ B . By Francisco-Fernando Granados. Dir. Francisco-Fernando Granados. Studio Theatre, Harbourfront Centre, Toronto. 26 April 2014.

[15] Granados, Spring 2015.

Return to Top»