Reconstruction Vol. 15, No. 1

Return to Contents»

Representing the Self through Ancestry: Meryl McMaster's Ancestral Portraits / Ellyn Walker

For each the self-portrait has been a place to think about subjectivity, to consider how to balance the fulcrum of being, to be at the same time both subject and object.

<1> Reflected in one's ancestry is the weight of history - histories that are as much about the legacies of family as they are about the self. By tracing a line back, whether straight or selective, ancestries offer a unique lens through which to view and, in turn, portray the self. Artists have long explored their ancestral backgrounds, homelands, and stories as inspiration for their artwork; however, it is Indigenous artists in particular who have focused on ancestry as a productive discourse for self-representation, and more importantly, as a potent symbol of Indigenous survivance. This notion, originally proposed by Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor, emphasizes the unequivocal survival of Indigenous peoples despite centuries of colonization. This essay concentrates on a specific body of photographic work by early career artist Meryl McMaster who uses composite self-portraits in order to create an ancestry of Indigenous pictorial resistance.

<2> Depictions of Indigenous peoples in North America have largely been shaped by practices of ethnography, which perpetuate notions of racial and cultural difference in relation to settler-colonialism.[1] Ethnographic portraiture, as typically practiced by white artists, has created an image-bank of Indigenous and non-white subjects that worked to extend photography's use as a colonizing tool. When the photographic camera came to North America in the early nineteenth century, commercial artists such as Francis Frith, A. Zeno Shindler, and William S. Soule were hired to capture the expanding "Western Frontier" and its Indigenous peoples as cultural artifacts whose images were to be documented "before their cultures vanished" (Tremblay 9). While this stereotype saw popularity throughout the nineteenth century, it is in fact the photograph that offers us proof that Indigenous peoples have always been present on this land.

<3> Early photographs that depict treaty signings, council discussions, and even ethnographic portraiture practiced by non-Indigenous artists form an important record of Indigenous presence and negotiation with European settlers. Indeed, artist and writer Gail Tremblay, of Onondaga, Mi'kmaq and French Canadian ancestry, explains that photographs such as Edward S. Curtis's ethnographic portraits reveal "a powerful resistance to the wholesale loss of the cultural autonomy and identity of native people" (9). While it is important to recognize the use of ethnographic portraits as colonial objects, these kinds of photographs hold multiple meanings, particularly for Indigenous viewers. These kinds of portraits represent an important record of Indigenous presence and visibility, explains Tremblay, a "refus[al] to "vanish" regardless of the punishment and oppression imposed upon them" (9).

<4> As a mode of representation, photographs are closely linked to notions of visual evidence to the extent that they are often regarded as a mirror image of reality. It is precisely this close relationship that plays an important role in Indigenous self-representation, where the photographic record offers proof that Indigenous peoples have never actually been "vanishing." Tremblay describes the myth of the "vanishing Indian" as the belief that "indigenous cultures were disappearing due to their innate inferiority" (8) to European cultural supremacy, and that they would eventually vanish completely. In her essay, "Constructing Images, Constructing Reality: American Indian Photography and Representation," Tremblay highlights how these kinds of representations have displaced settler responsibility "from the weight of their own brutality toward native people" (8). She states that "for an indigenous person, choosing not to vanish, not to feel inferior, not to hate oneself, becomes a political act" (8). Linking this to photography, Tremblay explains that "[e]very image a native photographer makes relates and reacts in very complex ways to [the] history of forced assimilation, and to the history of images of Native Americans" (9). Thus, the act of taking a photograph is a defiant gesture. In this vein, McMaster uses the photograph to emphasize the ways in which Indigenous resistance is revealed through ethnographic portraiture, drawing attention to histories of Indigenous and non-Indigenous self-representation, as reflective of her own position as someone of mixed Plains Cree and European ancestry living in Canada.

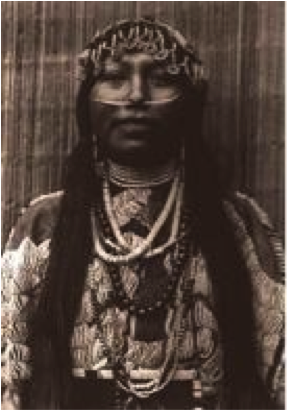

<5> Started in 2008, Ancestral is a series of layered photographs that feature an evolution of appropriated thematic imagery. Beginning with the black-and-white photographs of Curtis and Soule, and continuing through to the colourful paintings of George Catlin, McMaster's series also later includes jpeg photographs of wild animals, though these are not the focus of my study. In the first section of the series, McMaster appropriates ethnographic portraits, which she then projects onto her photographic subjects: herself and her father. In Ancestral 9 (2008) for example, we see a compound photograph of McMaster's upper body overlaid with Curtis's Wishham Girl photograph (1910) [see Figures 1 and 2]. The ornate jewelry of the "Wishham girl" - necklaces and headwear seemingly made of beads, shells and bones, along with body piercings - are now superimposed onto McMaster's face and neck, which stand out and take shape against her purposefully lightened skin. Through the application of theatrical white face makeup, McMaster highlights the ways in which whiteness has been imposed on Indigenous bodies and their cultures, and how Indigenous peoples have survived and succeeded in spite of assimilation policies, segregation (reservations) and violence.

Fig. 1. McMaster, Meryl. Ancestral 9. 2008. Digital chromogenic print. 40 x 30 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist and Katzman Contemporary.

Fig. 2. Curtis, Edward S.. Wishham Girl, from The North American Indian series. 1910. Photogravure. Edward S. Curtis Collection, Library of Congress, Evanston. LC-USZ62-136566.

<6> Layering is an important strategy for McMaster, allowing her the ability to portray Indigenous identity in multifaceted ways that move beyond the boundaries of cultural stereotypes. The two-dimensional projection onto McMaster's three-dimensional body creates a layered effect, which evokes both a distance and an interconnectedness between McMaster and the Wishham girl's bodies and, on a broader scale, a continuity between past and present histories of Indigenous representation and survivance. History is thus represented as a veil; one that viewers must continually look through in order to critically read her work. Tremblay describes this composite strategy of historical reframing as a common practice within Indigenous self-representation, where "photographs are altered, constructed, or collaged to create multiple layers of context" (10). McMaster's composite portraits also echo cultural theorist Stuart Hall's notion of identity as a kind of work that is never complete but is rather an ongoing project of self-discovery (Hall).

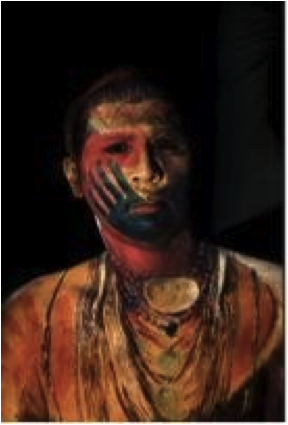

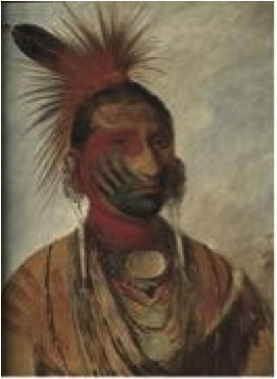

<7> In Ancestral 14 (2009), McMaster projects Catlin's vibrant portrait of Iowa Chief Fast Dancer (1844) onto the upper body of her father [see Figures 3 and 4]. Breaking away from the monochromatic and sepia-toned photographs in earlier parts of the series, McMaster's appropriation of Catlin's colourful portraits of chiefs and warriors makes it difficult to distinguish where McMaster's photograph of her father begins and where Catlin's painting of Fast Dancer ends. The seamless entwinement of the two photographs in Ancestral 14 are unsettling, forcing one to think critically about "his or her assumptions, and to seek new meaning in order to understand juxtapositions that are not always obvious" (Tremblay 10). Ultimately, McMaster's photographs reclaim ethnographic portraits in order to tell counter-narratives of Indigenous survival, perseverance and sovereignty.

Fig. 3. McMaster, Meryl. Ancestral 14. 2009. Digital chromogenic print. 40 x 30 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist and Katzman Contemporary.

Fig. 4. George Catlin. 'Wash-ka-mon-ya,' Fast Dancer, A Warrior. Iowa, 1844, oil, 29 x 24 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.520.

<8> The juxtaposition of historical and contemporary Indigenous representations within Ancestral reflects the ongoing negotiation that Indigenous peoples encounter with regards to sovereignty. Curator cheyanne turions suggests that "sovereignty manifests through intimacy, contact, and sociality as processes of negotiation" (27 March 2014), an insight into the embodied and relational nature of sovereignty that allows us to see McMaster's photographs in new ways. With this perspective, McMaster's images can be seen as playing what turions considers an important role in the shifting location of sovereignty "from the nation state to the self." Perhaps nothing is more exemplary of sovereignty than the gaze in McMaster's photographs, where there exists an undeniable intimacy in the "living eyes [that] pierce through the projections" (Morrissette and Myers 4). By way of her subject's acknowledgement of the gaze, and thus also through the viewer's implication in the process, McMaster's photographic portraits present a particular resistance to colonial subjugation that signals us to pay attention to the layered looks at play. In this potent articulation of resistance, both the historical and contemporary subjects' piercing gaze expresses Vizenor's notion of "survivance as an active repudiation of dominance, tragedy, and victimry" (Vizenor 15).

<9> In addition to the subject's piercing gaze, another tension is evoked in McMaster's photographs: the presentation of Indigenous subjects against the backdrop of Western art history - a history in which non-white bodies have been largely exoticized. McMaster's use of nudity subverts its function as a trope of colonial dominance and, instead, signals the physical and bodily undoing necessary for the deconstruction of identity. Looking again to the work Ancestral 14, the presence of McMaster's nude body rejects Catlin's ethnicized portrait of "an Indian in full dress." Although McMaster's series focuses specifically on representations of "Indianness," the push-and-pull between "being" and "being made up" asks us to consider how one makes sense of how photographs have been "constructed" rather than "captured." While this implies a critique of the photographer's intentions and the ways in which intentions frame photographs, the construction of images does not necessarily denote a subject's agency. As curator Andrea Kunard points out, "many Aboriginal people understood the power of the camera and adopted certain Eurocentric pictorial conventions as a means of empowerment" (49). Through rhetorical tactics such as the gaze, and, at times the pose, Indigenous subjects were able to negotiate and similarly communicate resistance in spite of their photographic exploitation.

<10> Also of note within McMaster's series is the use of her father as subject, which not only highlights the meaning of the work's title, but it also represents an important intergenerational practice of collaboration amongst Indigenous artists today. McMaster's practice follows the critical success of her father's career as a respected Canadian artist and curator. Gerald McMaster was the first Indigenous curator to represent Canada at the Venice Biennale in 1995 and was the co-curator of many blockbuster exhibitions such as Indigena: Contemporary Native Perspectives (1992). McMaster's familial practice reinforces how the interrogation of colonization remains important work across generations, as is also seen in the work of Jeff Thomas (Iroquois) and son Bear Witness (Iroquois/Cayuga). Métis scholar Sherry Farrell Racette explains, "Aboriginal people have a historical relationship with two distinct bodies of photography: the ethnographic salvage project [and] the emergent genre of family photography" (71). McMaster addresses these two sites or photo-colonialism in her work Ancestral - refusing to reject them - instead, re-contextualizing their images through contemporary photographic juxtapositions and embodied (self)-portraiture.

<11> The works in Ancestral reveal unique strategies of resistance intended to reconceptualize conventional representations of colony and nation in relation to contemporary Indigenous identity in Canada. In effect, McMaster's appropriations, contestations, and conversations with dominant photographs of Indigenous peoples disrupt Eurocentric readings of historical photographs by re-visualizing Indigenous selfhood. Her work engages collaborative photographic practices across generations to create nuanced portraits of Indigenous identity and, in doing so, threads together generations of artistic and social resistance. The ethnographic photographs that overlay McMaster's contemporary Indigenous subjects stage confrontations between ideologies of the past and realities of the present.

Notes

[1] Settler-colonialism functions as a process of land occupation and colonization that involves the profound displacement and oppression of Indigenous

societies.

Works Cited

Bright, Susan, Auto Focus: The Self-Portrait in Contemporary Photography. New York, NY: The Monacelli Press, 2010. Print.

Morrissette, Suzanne and Lisa Myers, past now. Barrie: McLaren Art Centre, 2010. Catalogue.

Nairne, Sandy and Sarah Howgate, The Portrait Now. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006. Print.

Payne, Carol and Andrea Kunard eds., The Cultural Work of Photography in Canada. Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011. Print.

Pearlstone, Zena and Allan J. Ryan, About Face: Self-Portraits by Native American, First Nations, and Inuit Artists. With essays by Joanna Woods-Marsden, Joanna Roche, Janet Catherine Berlo and Lucy R. Lippard. Sante Fe, NM: Wheelright Museum of the American Indian, 2006. Print.

cheyanne turions, "A Table for Negotiation, Mediation, Discussion, Difference," curatorial research blog, March 22, 2014. Web. http://cheyanneturions.wordpress.com

Vizenor, Gerald, Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. Print.

Return to Top»