Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 2

Return to Contents»

Changing LGBT Narratives in Turkish Cinema / Murat Akser

Abstract

From its inception, depiction of sexuality on screen outside of heteronormative behavior has consistently been met with censorship by the state and negative criticism from the media. Yet, beginning with mid 1960s and spanning latter decades, Turkish filmmakers have become far more open and daring in their depiction of the gay and lesbian relationships. It is the aim of this essay to outline a history of LGBT representations in Turkish cinema over the last fifty years, depictions progressing from lesbian to transsexual and finally to homosexual males during the period, 1962 to the present.

Keywords: Turkey, LGBT, gay, queer, lesbian, homosexual, Turkish cinema

<1> Turkish cinema gave visibility to gay, lesbian and transgendered characters from the 1960s onward. From its inception, the depiction of sexuality on screen-outside of heteronormative behavior-has consistently been met with censorship by the state and with negative criticism from media. Yet, beginning with the mid-1960s, Turkish filmmakers have become far more open and daring in their depiction of gay and lesbian relationships. It is the aim of this essay to outline a history of LGBT representations in Turkish cinema in the last fifty years, progressing from lesbian to transsexual and finally to homosexual males in in the period, 1962 and 2012. So much has been achieved in the last ten years, and perceptions of LGBT individuals have changed for the better in Turkey. Today, universities have LGBT student clubs, there are two queer and trans film festivals that are increasingly popular, and there are gay pride parades in several cities of Turkey yearly. LGBT groups have shown to the world their politically strength during the Taksim Gezi Park protests in 2013, suggesting that discussions of lesbians, transsexuals and gays are no longer taboo.

<2> In the early history of Turkish theatre, men cross-dressed as women, as Islam forbid women from acting in public. Men wore women's clothes, or Christian or Jewish women were allowed on stage. Afife Jale (1902-1941) broke with tradition in 1919 to become the first Muslim Turkish woman to appear on the theatrical stage. The appearance of women in Turkish cinema, however, dates much earlier, to 1917 with Pençe (The Claw), as Bedia Muvahhit (1897-1994) made her debut. From her appearance to the 1960s, any suggestion of homosexuality remained taboo, so males and females alike participated in a charade, living their lives under the guise of heteronormative romances. A closeted homosexual singer, songwriter and actor, Zeki Müren (1931-1996) never had the chance to come out in the 1950s and 60s and, instead, appeared as the gallant heterosexual male hero in all his films (Arslan 2012). The political freedoms of the 1961 Constitution and liberal ideas of the 1960s allowed the filmmaker Halit Refiğ (1934-2009) to create the first on-screen lesbian couple. Film historians credit two other films shot around the same time asFour Women in the Harem (Haremde Delört Kadin, 1964) as including the first lesbian kiss in Turkish cinema (Figure 1). The first film is Ver Elini İstanbul (Istanbul Come My Way, 1962) is scripted by Attilâ İlhan (1925-2005) and directed by Aydin Arakon (1918-1982). In this film two women, Mualla Kavur and Leyla Sayar b. 1939), kiss. The other film is Iki Gemi Yan Yana (Two Ships, Side by Side, 1963; Figure 2), scripted by novelist and intellectual, Kemal Tahir (1910-1973), and directed by the legendary Atif Yilmaz (1925-2006). Aysel (Suzan Avci, b. 1937) and Sevda Nur (1944-2011) share a kiss. The film was banned from cinemas by the authorities for "aiming to corrupt the Turkish traditional family structure." These two kisses are, truth be told, no more than rapid short touches on the lips by two characters who are more friends than a lesbian couple. The more serious relationship and a long passionate kiss between two women follows in Four Women in the Harem.

An Early Pioneer: Four Women in the Harem

<3> A 1965 historical drama, taking place in the harem of Sadik Pasha, is the first Turkish film to include a lesbian love affair and screen kiss between two women (Figure 3). Director Refiğ came from an affluent bourgeois family and was trained in Robert College in Istanbul as an engineer. After his military service in Korea where he shot super 8mm documentaries, he returned to Turkey to work as a film critic. In the late 1950s, he worked as assistant director under Atif Yilmaz and launched his career with the romantic drama, Yasak Aşk (Forbidden Love, 1961). Refiğ openly admits an interest in psychoanalysis, as well as with forbidden affairs and Turkish history in clash with westernization. He and several other film director friends, in fact, helped Refiğ create a new film moment they called National Cinema. He has made Four Women in the Harem at the height of this movement. He created his male characters to represent East and West and his women to represent the communalism of the Empire versus the heteronormative Young Turk nationalism of a decent young woman. Aside from metaphors, the film openly showed an elder member of the Pasha,s harem kissing a less experience woman. The open implication was that they are not only kissing but that they are also going to bed with each other.

<4> The film takes place in late nineteenth-century house of a corrupt pasha, a notable member of Sultan's cabinet who sells his favors to foreign ambassadors in return for gold. He has two nephews, Dr. Cemal (Cüneyt Arkin, 1937-), a Western-educated doctor, and Rüstü (Tanju Gürsu, 1938-), an Eastern-trained soldier. The three women of the harem are involved in relations with each other, as well. Sevkidil (Ayfar Feray, 1928-1994) is an elderly matron, Migrengizn (Birsen Menekseli, 1940-) is emotionally unstable, and Gülfem (Parvin Par, 1939-2015) is a nymphomaniac who desires to bear a child to claim Pasha's legacy. Sevkidil manages the harem and wants to maintain control over the house and pasha. She tries to block the influence of the younger fourth wife, Ruhsan (Nilüfer Aydan, 1940-). Migrengiz's wooing of Ruhsan implying that she should have engage in a lesbian affair female head of the household and maintain a heterosexual affair with the symbolic head (Sadik Pasha). Unable to control Ruhsan, who has an affair with the physician, and Gülfem, who has sex with the other nephew Rüstü, Sevkidil finds consolation in having an affair with the second wife, Migrengiz.

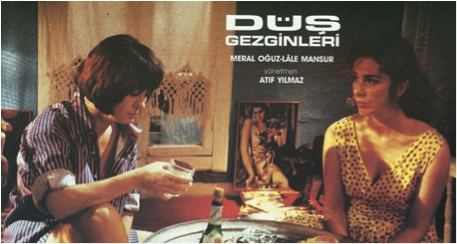

<5> The screenplay was written by a prominent Marxist, Kemal Tahir (1910-1973), who wanted to integrate Eastern and Western ideals of socialism into his writings. The depiction of the lesbian affair between Sevkidil and Migrangiz is, in this context, all the more important as the symbol of the self-consuming and corrupt Empire that seduces and rapes its Arab provinces across the different regions of the Empire.

|

|

|

Figure 1. First lesbian kiss Figure 2. Iki Gemi Yan Yana (1962) Figure 3. Four Women in the Harem (1964) |

||

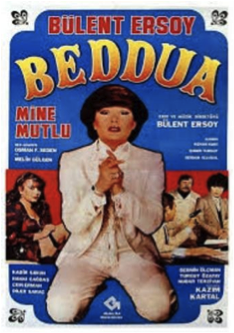

The 1970s: Exploitation and Trans-Apologetic Cinema of Bülent Ersoy

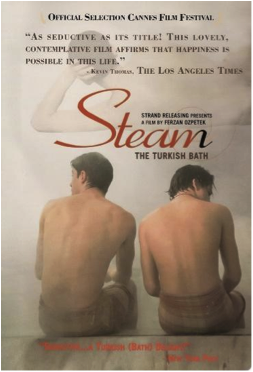

<6> The latter half of the 1970s, further opportunities for such representations arose in Turkish filmmaking practices as the production of soft-core porn production skyrocketed. As part of this fury, women as the subject of male gaze were needlessly and dispassionately made to kiss each other under the pretentions of lesbian sexual relations. Toward the end of the decade, the redoubtable singer of Ottoman music and prominent trans actress, Bülent Ersoy (1952-), appeared in two important films where she had to play "himself" as a character and publicly humiliate himself with his exposure as a transgender artist (Figure 4). As a man, he had been a massively successful singer in Turkey during the 1970s and had made it known publically that he wished to undergo surgical gender reassignment. He eventually achieved his aim and became a woman. But prior to his operation, his appeared in two films as a victim of perverted lifestyle and was forced to set an example to youth the woes of a life living in sin (Altinay 2008). The first film, directed by Osman F. Seden (1924-1998) and entitled Beddua (Curse, 1980), depicts Bülent as a sexual deviant who had been raped as child. Later, his trans identity is denied, and instead he is constantly referred to as homosexual. The image of the gay/trans individual in Turkish cinema, then, came to be represented as someone who wears a fur, heavy makeup and has indiscriminate sex with men and women. More to the point, they are seen neither as men nor women.

<7> Made soon after the 1980 military coup intent on shaping Turkish society in a militarist image, the other film, Söhretin Sonu (The End of Fame, 1981), is designed to be "an apology" for Bülent Ersoy (Kabalamaci 2014). In the film Bulent's queer identity is attributed to his interest in playing with girls' dolls as a child. Within the film, he performs in a casino as an adult crossdresser. Later in the film, he "apologizes" to the public for his inappropriate behavior and, thereafter, "reclaims" his masculine gender (Ertür and Lebow 2014).

|

|

|

Figure 4. Bülent Ersoy as a troubled transsexual in Beddua and Söhretin Sonu |

||

Atif Yilmaz's Cinema of Gender Reversal

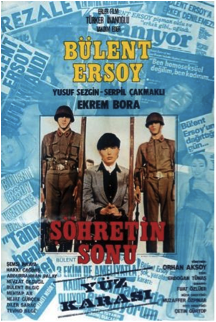

<8> In the 1980s, the director-actress duo of Atif Yilmaz and Müjde Ar (1954-) went on to make feminist films with strong female leads. By the early part of the decade, Atif Yilmaz was already recognized since the 1950s as a seasoned director with a long track record of delivering fast, high-quality popular Turkish films. Starting with 1982 film Mine (released in the Soviet Union in 1985), he entered his so-called "woman phase" as a director. Yilmaz was introduced to feminist ideas by his partner and women's rights activist, Deniz Türkali (1944-). In fact, Yilmaz would team up with young actress Müjde Ar no less than five times between 1984 and 1986 in a series of feminist films that allowed her the role of a woman who would stand against the traditional role of women as passive wives in Turkish society. As a young actress, she came to prominence playing the young lustful girl in the Refiğ-directed Forbidden Love (Aşk-ı Memnu) romantic television series that would propel her to overnight stardom in Turkey. In 1985, Yilmaz directed Ar in Dul Bir Kadin (A Widow). Here, two women who experience betrayal, misery and violence at the hands of men decide to share their lives with each other. The film was infamous at the time for showing two female character naked in the same bed, doubtlessly implying sexual involvement between them the night before.

<9> In the film, Müjde Ar appears in the role of Suna, a recently widowed wife; her husband had died two years earlier. Her immediate bourgeois circle of friends is decidedly dull and rife with women hunting for rich husbands. She is matched by her matchmaking friends with old men who are not sexually attractive but who are, nonetheless, socially acceptable as affluent future spouses. In a chance encounter, Suna is introduced to Engin (Yilmaz Zafer, 1956-1995), a professional photographer, in an antique shop run by Gönül (Deniz Türkali) antique. Engin later reappears at Suna's house party, and the two have sex that night. Meanwhile, Suna's best friend, Ayla (Nur Sürer, 1954-), has just come out of aturmultuous eight-year relationship with a married man who dumps her for a younger woman. After Ayla's failed attempt at suicide, Suna offers to accompany her on a vacation to Bodrum, a port city in southern Turkey. Suna has also invited by Engin. Arriving in Bodrum, Suna and Engin immediately embark on a relationship, at once both passionate and sexually fulfilling. Younger than Suna, Engin is physically attractive yet but superficial, and he mistreats Suna: he sleeps with other women and invites Suna join in a ménage à trois. In desperation, she confides in Ayla, and they spend the night together, naked in the same bed. We never witness what takes place in the space of that night. What the film shows, however, is two naked women, one lying atop the other. Whether the shot is friendly or erotic remains at question, but it gives Engin the inspiration to photograph two women together. In a series of created shots, Suna and Ayla depict an alienated lesbian couple on the streets of Bodrum. Yilmaz, as director with a professed interest in such matters, presents his fantasies about lesbian love in an imaginary artistic medium of photography, as opposed to an overt, straightforward display showing them as a lesbian couple (Figure 5). Not surprising, these images are beautifully choreographed by Şahin Kaygun (1951-1992), himself renowned as a pioneering photographer and film director.

<10> Engin's immature and imbalanced personality hurts Suna as he pursues a possible affair between himself and Suna-Ayla. In a particular scene, the three of them go to swim together in the sea; Engin offers to remove his underpants and quickly does that. Ayla in return removes only her bra. The two then forcefully strip Suna of her bra and panties. Symbolic, Ayla inserts herself into as she claims an erotic part of Suna's sexuality, foreshadowing their eventual lesbian relationship. Later, Suna discovers that Engin has slept with Ayla. Disappointed and ashamed, Ayla leaves, abandoning Suna to the will of an abusive Engin. In the end, as she attempts to escape, Engin begins to beat her, saved, only saved by the arrival of her thirteen-year old daughter. Returning to Istanbul, she discovers a close and romantic love with Ayla. It is only within the context of two women as victims that an overt lesbian coupling is permitted; their coming together arises from a greater-and nonthreatening-desire to protect each other.

|

|

|

Figure 5. Two women find happiness away from abusive men and in each other's arms in Dul Bir Kadin |

||

<11> Atif Yilmaz continued to explore the relationship between two women with erotic romance, Düş Gezginleri (Walking After Midnight, 1992), credited as the first feature-length Turkish film to premiere at a queer film festival in 1994 (in this instance, the Torino Gay and lesbian Film Festival). This film is exceptional for its depiction of a lesbian relationship as normal and acceptable, reflecting in all likelihood a loosening of the reigns of censorship rules by the Turkish state following national elections in 1991. But insofar as the film fails in portraying lesbian women as acceptable to the decree expected in heteronormative relationships, it does nonetheless frame its shots in such a way as to promulgate and perpetuate a heterosexist gaze.

<12> Within the film, Nilgün (Meral Oğuz , 1955-) is a doctor, recently separated from her husband, who has been appointed to work in a small hospital in an Aegean town. One day, she is ordered to visit a brothel for health inspection, and while there, she meets her childhood friend Havva (Lâle Mansur, 1956-), who has now become a prostitute. She has disguised herself using Anjelik as her alias, but Nilgün recognizes her by a birthmark on her back.

<13> Both women immediately fall in love with each other and move in together. It is a small town where men and women alike are prone to gossip about them. By law, Havva cannot leave the brothel. Mistreated by the locals, they plan to leave for Istanbul, and it is at this point in the film that we are made aware of a difference in social. Back in Istanbul, Nilgün still sees her ex-husband: she goes to a giant homecoming party together with Havva, who this time appropriates another alias, one that more attuned to the mores of high society, to impress Nilgün's immediate bourgeois circle of friends. Their relationship collapses after the couple experience a series of jealousy fall-outs. In order to secure a new space for a clinic, Nilgün sleeps with a rich man who makes his affections for her known. At the same time, Havva poses nude for the upstairs partner, Olay (Deniz Türkali), who is likely a lesbian. Nilgün's anger arises to the physical level, and she slaps her-in precisely the same manner that a man might in an abusive heterosexual relationship. Interestingly, when dealing with issues of gender and class, the film follows along the same lines of the 2013 French coming-of-age romantic film, La Vie d'Adèle - Chapitres 1 & 2 (Blue is the Warmest Color, directed by Abdellatif Kechiche [1960-]), where the two female lovers are separated by differences in social class.

<14> Important to note, the film is a testament to the dual hypocrisy surrounding acts of sexuality in Turkish society. For example, when Nilgün rents a house from a rich townsman Nafiz (Yaman Okay, 1951-1993), who quite obviously desires her, it is his wife who immediately comes and courts her. In a series of touches, first on her hands, her lips and finally between her legs, the wife openly invites a lesbian affair, suggesting that it is safer this way. That is to say that she can in this guise preserve the family, keep the woman away from her husband and enjoy a sexually robust and fulfilling relationship herself. In the meantime, the husband sleeps around with prostitutes and eventually and eventually falls into Havva's arms, if for no other reason than because he is jealous of her affair with Nilgün. In fact, Nilgün is constantly subjected to pressures to marry, and eventually Ali (Memduh Ün, 1920-2015), as the head of the hospital, forces her to marry a widowed dentist as "it is the right thing to do."

|

|

| Figure 6. The first openly lesbian characters in Düş Gezginleri | |

The Trans-Turn: The Night, Angel and Our Gang

<15> In 1993, two films focused on trans identities were made back to back. The first is Dönersen Islık Çal (If You Start Whistling Play). Here, a transsexual and a dwarf share a moment of intimacy on the streets of Istanbul. This is also the first time in Turkish film history that a trans character is unapologetically given the lead. Orhan Oguz (1948-), the DOP of the 1985 film A Widow, directs with Cemal San (1966-) as the scriptwriter. The second film is directed by Atif Yilmaz. An interesting to note, he would follow up this depiction with his revolutionary film, representing realistic trans and gay characters, Gece melek ve bizim çocuklar (The Night, Angel and Our Gang, 1994). The film features Serap (Derya Arbas, 1968-2003), Hakan (Rony Uzay Hepari, 1969-1994) and Melek (Deniz Türkali). These three character, however much they might mirror each other, represent stages of development towards their own lives and views of view (Figure 7). Serap is a prostitute who solicits customers off the streets. She meets a trans individual who first robs her and then becomes her best of friends. Together, they meet Hakan, a male prostitute but falls in love with Serap. Melek, an old woman once imprisoned for having stabbing the man she loved, becomes enraged with jealousy and picks fights on the street with any man who stares at Serap too long.

<16> In addition to these three, we see a trans character who works as a prostate to pay the bill for a sex-reassignment surgery. Melek, herself a former prostitute, loves Hakan's boss Osman (Cengiz Sezici, 1950-) and is in the end killed by him. And then there are the police who constantly harass and hunt transgender individuals. Class differences again come to the fore as Hakan and his gay lover, a professor, fail to understand the sentiments of the other. When Serap catches them having sex, she leaves Hakan.

<17> Later, Remzi (Kaan Girgin, 1967-) picks Serap up one night. They ride while he drinks, and eventually he takes her to a party. Here, Serap becomes enamored with the lifestyle of the rich and wishes to have such a life on her own merits: she leaves town to in search of her riches as a singer. Serap realizes that she does not prefer Hakan and cannot marry a man who would force her to suffer an impoverished life. She deserts Melek, who herself has lived a calamitous life, and does the "smart thing," consciously and knowingly selling her body as she strives to become "someone" in society. The film ends with a celebration of a sort, at the birthday party of a very rich woman.

|

|

|

| Figure 7. The three characters engage with each other | ||

The 1990s: Side Characters and Hamam/The Steam Bath

<18> In the late 1990s, queers were represented on screen mostly as side characters. Director, producer and screenwriter, Mustafa Altioklar (1958- ), however, had taken a chance and made his first feature-length film Denize Hançer Düştü (A Dagger Fell into the Water) about homosexuality in 1992. The films focuses on two actresses in love. Two additional films by Mustafa Altioklar, Istanbul Kanatlarimin Altinda (Istanbul Under My Wings, 1996) and Ağır Roman (Cholera Street, 1997), feature openly gay characters who are mistreated by society. In the former, a historical drama set in the seventeenth century, the gay lover to Sultan Murat IV is murdered by a band of soldiers for his having exerted an undue influence on the Sultan. The ruler makes a heterosexual turn and ultimately takes revenge by ordering the execution of his newly beloved. In Cholera Street, Orhan, an openly gay friend of the local Mafioso boss, Salih (Okan Bayülgen, 1964-) is mistreated, beaten and saved by death by Salih. The role of Orhan is played, in a node to realistic representation, by a famous gay poet Küçük İskender (1964- ). Director and screenwriter Ferzan Özpetek (1959-) made Hamam (The Steam Bath; originally released as Il bagno turco) in 1996 as his first feature. Ozpetek, who lived in Italy and had studied the history of cinema at Sapienza University of Rome and art history and costume design at the Navona Academy, would go on to direct a number of films with international funds and crew, among them Harem Suare (Harem Suare, 1999), relating the tormented love story between the Sultan's favorite, Safiye (Marie Gillain, 1975-), and the eunuch Nadir (Alex Descas, 1958- ); Le Fate ignoranti (His Secret Life, 2001), exploring the complex nature of homosexual and friendship; Bir ömür yetmez (Saturn in Opposition, 2007; originally released as Saturno contro), exposing the tensions between three very close couples, two straight and one gay, in the wake of the death of a dear friend; the Tribeca Film Festival Special Jury Prize-winner Mine vaganti (Loose Cannons, 2010), in which Cantone brothers from a prominent if conservative Southern Italian family, Tommaso (Riccardo Scamarcio, 1979-) and Antonio (Alessandro Preziosi, 1973-), struggle with coming out to their families and must face the potentially dire consequences; and Magnifica presenza (A Magnificent Haunting, 2012), a charmingly quaint tale in which Pietro Pontechievello (Elio Germano, 1980- ), a gay man, rents a large house haunted by the ghosts of a theater company from the fascist period. Notably, when the focus is on life in Turkey, each of Özpetek's films takes a very Orientalist approach to the representation of gay lives.

|

|

| Figure 8. Ferzan Özpetek's gay lovers in Hamam and Küçük İskender in Cholera Street | |

The 2000s: Kutluğ Ataman's heroes, Lola + Bilidikid and Two Young Girls

<19> The gay artist Kutluğ Ataman (1961- ), born in Istanbul and residing in London, has made two important films dealing with LGBT representations (Figure 9). [1] The first is Lola + Bilidikid (1998), betraying with a sophisticated balance of humor and violence the plight of gay Turkish men living in Germany who struggle against prevailing prejudices directed toward difference in race and sexual identity (Clark 2006). His Golden Orange Award-winner İki Genç Kız (Two Young Girls, 2005), presents the relationship between Behiye (Feride Çetin, 1980- ) and Handan (Vildan Atasever, 1981-), two 20-something urban-styled girls from different classes who appear "too close" and must endure the perils of life in a male-dominated Turkey (Kilicbay 2008).

<20> Similarly, the German/transnational director, screenwriter and producer of Turkish descent, Fatih Akin (1973- ) weaves a lesbian tryst involving Turkish student and rebel Ayten Öztürk (Nurgul Yesilcay, 1976- ) into the storyline of his German-Turkish cross-cultural tale, Auf der anderen Seite (Yaşamın Kıyısında or Edge of Heaven, 2007). Germany's entry in the Academy Awards, this work went on to receive the Prix du scénario at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival (Berghahn 2009).

|

|

| Figure 9. Gay and lesbian characters in Lola + Bilidikid and İki Genç Kız | |

The Millennial Turn: Nar and Zenne

<21> Recent Turkish cinema demonstrated an uncanny ability for realistic representation of LGBT characters in complex ways (Figure 10). Popular singer-turned-director Mahsun Kırmızıgül (1968-) turns his attentions in what has been called his melodramatic epic, Güneşi Gördüm (I Saw the Sun, 2009), to the plight of a Kurdish family forced from their village in southeastern Turkey by the decades-long ethnic and political conflicts tearing apart their region. His examination of the futility of hatred is echoed succinctly in the image of a transgender drag queen Fifi (Seyhan Arman, 1980-), who is murdered by a family member for dishonoring the family name. Shortly thereafter, Zenne Dancer (Zenne, The Male Dancer, 2012), directed by M. Caner Alper (1970- ) and Mehmet Binay (1972-), was released to the general public. Inspired by true stories, the poignant film concentrates on an unlikely trio of gay friends. Daniel Bert (Giovanni Arvaneh, 1964-) is a German photojournalist who resides in Istanbul but does so without much knowledge of Turkish values. Can (Kerem Can, 1977-) is a flamboyant, openly gay and proud male belly dancer who enjoys the love and support from his family. Ahmet (Erkan Avci, 1982-), a university student born into an Eastern and conservative family, seeks dignity, honesty and personal liberty but comes to a tragic end at the hands of his father, who refuses to accept that his son is gay.

<22> The following year, director, screenwriter and author, Ümit Ünal (1965-), brought out his carefully crafted thriller NAR (Pomegranate, 2011). Within the confines of their single-room apartment, two strong-willed lesbian characters—tellingly, they remain unnamed, but played by İrem Altuğ (1980-) and İdil Fırat (1972-), both of whom are in reality heterosexual—set about the process of living their lives unashamedly. The film was immediately heralded for its realistic and normalizing depiction of two women completely committed to a lesbian affair.

|

|

Figure 10. Contemporary representations and Çağan Irmak: Blockbuster Closet Queerism |

|

<23> The new millennium has borne witness to a series of melodramatic films written and directed by television director Çağan Irmak (1970- ). Noted for his instant rapport with actors, his works have resulted in stunning performances. His writing style found to be intimate, he is capable of unfolding unveiling character conflicts with melodramatic results. From his first film onwards, he focused on the depiction of closeted homosexuality in all of his films. His first feature-length work, Bana Şans Dile (Wish Me Luck, 2001), involves a high school student's taking his class captive and forcing them to confess publicly to sins of shame. One "jock," an athlete who had thrived as the class bully, is himself bullied into revealing his secret double life as a male prostitute.

<24> Later, his Issiz Adam (Alone, 2008) [2] would mark an important point in his cinematic career. A film focused on Alper (Cemal Hünal, 1976- ), a single man in this thirties, determined to experience all kinds of sexual acts, including having sex with a couple (a man and a woman)—he tries to fall in love but cannot-he finds himself going through the motions of romance (Figure 11). He meets a young girl, Ada (Melis Birkan, 1983- ), and embarks upon an affair in which they have sex frequently. Finding himself "lost" and unable to commit himself fully, he abandons her. When confronted by Müzeyyen (Yildiz Kültür, 1944- ), his mother, as to why he cannot purse this relationship with a woman who loves him, he responds, with a sense of desolation and self-alienation, that "it is not easy it. It's very, very difficult, mother." In fact, we gain insights into his life while running a Western-style restaurant. Notably, his friends and confidants are all men. In a chance encounter with Ada in front of a movie theatre-he is there with his chef-cum-confidant—sometime later, he learns that she is married and has a child. Their inner voices betray personal regret, and with the final shot, we see him walking alone on an isolated beach, a stick in hand. He observes a girl dancing and smiles, ironically. Might she be another younger version of Ada, growing up innocently, who will one day fall victim to the likes of Alper? Is it his admiration of youth or his life renewing itself that he now feels? Answers are never forthcoming. With this enigmatic end, we also witness Irmak's willingness to (mis)lead his audience to believe that they are watching a heterosexual romance unfold; indeed, we are confronting male characters who despise bourgeois family lifestyle of heterosexual married couples. Desolate, he stands outside the system, alone and in seclusion, to explore his own (ambiguous or queer?) sexuality.

<25> More recently, Irmak's film Tamam miyiz? (Are We Done Yet? 2013) continues his exploration of the closeted homosexual in contemporary Turkish life. In this instance, we learn of an unlikely relationship between two men: Temmuz (Deniz Celiloglu, 1986), a gay sculptor stressed over his gay identity and the other, Ihsan (Aras Bulut Iynemli, 1990- ), who must come to grips with Tetra-amelia Syndrome, a rare congenital disability leaving him a quadriplegic. Other areas of his body, among them his reproductive organs, his anus and his pelvis, are likely affected by similar malformations. Hence, the two men live -survive within—a romantic relation in the absence of sexual activity.

|

|

| Figure 11. Always alone in Issiz Adam | |

Conclusion

<26> Doubtless, Turkish LGBT cinema has come a long way since 1962. Revelations of lesbian representations wherein exploration is often the norm were followed in the 1990s with significant and significantly compelling representations of Trans individuals. Many might have believed that, by the second decade of the new millennium with its cinematic representations of openly gay men, homosexuality had reached new levels of dignity and acceptance. And certainly filmic depictions would suggest as much. For the first time in 2015, however, Turkish authorities moved to ban the annual Gay pride parade. Police were quick to respond, hurling canisters of tear gas, firing rubber bullets and unleashing water cannons against those who dared march in celebration. Questions of dignity aside, will the Turkish cinema address efforts to erase years of progress in a responsible and accurate manner?

Acknowledgement: Unless otherwise noted, all images were acquired under a Creative Commons license.

Notes

[1] It is also interesting to note that at the 48th Venice Biennale Ataman presented his visual arts piece, Women Who Wear Wigs (1999), featuring images of four women, namely a revolutionary whose face remains obscured, a well-known journalist and breast cancer survivor Nevval Sevindi, an anonymous Muslim student devout in her religious practices, and an social activist/ transsexual prostitute.

[2] The title Issız Adam is itself a triple entendre, meaning at once "Abandoned Man," "My Abandoned Island," and "My Lonely Ada," Ada is the name of the female lead character.

Works Cited

Akser, Murat. "Women and Turkish Cinema: Gender Politics, Cultural Identity and Representation." Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 34.1 (2014): 116-119.

---, and Bayrakdar, D., eds. New Cinema, New Media: Reinventing Turkish Cinema. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014.

Altinay, R. E. "Reconstructing the Transgendered Self as a Muslim, Nationalist, Upper-Class Woman: The Case of Bulent Ersoy." WSQ: Women's Studies Quarterly 36.3 (2008): 210-229.

Arslan, U. T. "Sublime Yet Ridiculous: Turkishness and the Cinematic Image of Zeki Müren." New Perspectives on Turkey 45 (2012): 185-213.

Atakav, E. Women and Turkish Cinema: Gender Politics, Cultural Identity and Representation: Gender Politics, Cultural Identity and Representation. London: Routledge, 2012.

Berghahn, D. "From Turkish Greengrocer to Drag Queen: Reassessing Patriarchy in Recent Turkish/German Coming-of-age Films." New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film 7.1 (2009): 55-69.

Çakirlar, C. "Aesthetics of Self-scaling: Parallaxed Transregionalism and Kutluğ Ataman's Art Practice." Critical Arts 27.6 (2013): 684-706.

---. Disidentification, Mimicry, Melancholia and Image: Queer Reconfigurations in Contemporary Visual Arts. Doctoral dissertation, University College London, 2008.

---. "Queer Art of Parallaxed Document: The Visual Discourse of Docudrag in Kutluğ Ataman's Never My Soul!" Screen 52: 358-375.

Clark, C. "Transculturation, Transe Sexuality, and Turkish Germany: Kutluğ Ataman's Lola und Bilidikid." German Life and Letters 59 (2006): 555-572.

Ertür, B., and Lebow, A. "Coup de Genre: The Trials and Tribulations of Bülent Ersoy." Theory & Event 17.1 (2014).

Gorkemli, S. Gender Benders, Gay Icons, and Media: Lesbian and Gay Visual Rhetoric in Turkey, 2011. http://www.berfrois.com/2011/11/turkish-queer-icons/

Gorkemli, S. "Coming Out of the Internet": Lesbian and Gay Activism and the Internet as a "Digital Closet" in Turkey. Journal of Middle East Women's Studies 8.3 (2012): 63-88.

Kabalamaci, A. D. M. "Being The Shame of Society: The Construction of Hegemonic Masculinity in the Film Şöhretin Sonu (The End of Fame)." İstanbul Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Hakemli Dergisi 46 (2014), 37-56.

Kahraman, H. B. "The End of the 'New' as We Know It: Post‐1990 and the 'New 'Beginnings in Turkish Culture." Third Text 22.1 (2008): 21-34.

Kılıçbay, B. "Queer as Turk: A Journey to Three Queer Melodramas." In R. Griffiths, ed. Queer Cinema in Europe. Bristol, UK: Intellect Books, 2008. Pp. 117-128.

Kılıçbay, B. (2006). Impossible crossings: Gender melancholy in Lola+ Bilidikid and Auslandstournee. New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film 4(2).

Okumuş, F. "Sıradışı Cinsel Yaşantılarımız ve Sinemamız (Our Outrageous Sexual Experiences and Our Cinema)." Kurgu (2003): 183-204

Selen, E. "The Stage: A Space for Queer Subjectification in Contemporary Turkey." Gender, Place & Culture 19.6 (2012): 730-749.

Return to Top»