Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 2

Return to Contents»

Performing Authorship in a Queer Time and Place: A Case Study of Yonfan / Shi-Yan Chao

Abstract:

An examination of the work of Chinese diasporic gay filmmaker Yonfan, with special attention to his Bugis Street (妖街皇后Yao jie huang hou, 1995) and Bishonen (美少年之戀Mei shao nian zhi lian, 1998), leads to a reappraisal of the meaning of gay authorship. Making use of the various intertextual discourses, Yonfan locates queer connotations in a historically sensitive, transnational framework, suggesting as he does so that recurring themes and particular stylistics are inscribed in terms of queer space, queer temporality/affect, and queer aesthetics and pleasures. These, I contend, are foundational to the "mise-en-scène of desire" that notably privileges non-normative desires and subjects for an emerging Sinophone queer counterpublic. That is to say that he performs his gay authorship within a queer time and place where we might find intimate connections and belonging beyond the heteronormative social institutions.

Keywords: gay authorship, queer space, queer temporality, queer affect, Sinophone counterpublic

<1> Yonfan is a diasporic filmmaker. Born in Wuhan, China in 1947, he spent his early years first in Hong Kong and then in Taiwan. He returned to Hong Kong as a photographer at the age of seventeen but left for study and travel in the United States, France and Britain in his early twenties (Yonfan 2012). Returning to Hong Kong at twenty-six, he earned a reputation as a gifted photographer best known for his celebrity portraits. He made his film debut with A Certain Romance in 1984. Since that time, he has made ten additional features, among them Lost Romance (1986), Last Romance (1988), Bugis Street (1995), Bishonen (1998), Peony Pavilion (2001) and Tears of Prince (2009). While the majority of his features have been filmed in Hong Kong, he has also shot films in Macao, Singapore, Taiwan and China. For many, Yonfan's work is first and foremost characterized by a profound sense of beauty and romance (weimei langman). As a filmmaker whose gay identity has been something of an "open secret" for years, his early depictions of queer identity came with representations of lesbianism in Immortal Story (1986). His later depictions of transgenderism in Bugis Street and male homoeroticism in Bishonen, however, are perhaps far better known.

|

|

| Figure 1. Poster of Bugis Street | Figure 2. Poster of Bishonen |

<2> The attention I give to Bugis Street and Bishonen as I appraise the significance of Yonfan's queer authorship, in fact, echoes Mikhail Bakhtin's notion of the author, who is by no means the sole proprietor of an utterance, but is instead the "orchestrator" of utterances, wherein the artistic image or word is always a hybrid construction mingling voice with that of others (Stam 1989: 191, 199). Against the romantic misconception of total originality in authorship, my approach shares much in common with Richard Dyer's author-as-performer model, insofar as both understand "the author as a real, material person, but in … a 'decentered' way" (1991: 188). In other words, it still matters who specifically makes a film and whose performance a film is, but of crucial importance, following Dyer, are both "the authors' material social position in relation to discourse, the access to discourses they have on account of who they are" and, in the case of gay filmmakers in particular, their "access to, and an inwardness with, lesbian/gay sign systems that would have been like foreign languages to straight filmmakers" (1991: 188). Reconfiguring his formulation, my analysis appeals less to a somewhat closed subcultural system; it rather draws attention to the trans-local, diasporic dimension in Yonfan's performance of authorship. All local and trans-local queer discourses, then, are essential to his processing of his personal diasporic position within a globalizing culture. More to the point, all these discourses are crucial to his establishing of his affiliations with a queer-identifying counterpublic in the transnational Sinophone culture.

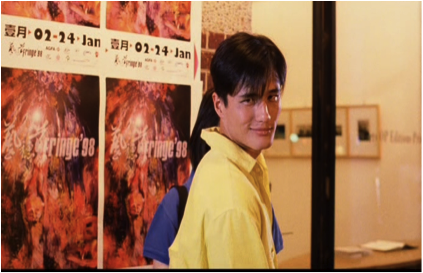

<3> My use of the term "counterpublic" follows Michael Warner's formulation that foregrounds the idea of "multiple publics" and an awareness that "some publics are defined by their tension with a larger public" (2002: 56). It is structured by "alternative dispositions or protocols." With its participants maintaining "an awareness of [their] subordination status," a counterpublic is likewise mediated by diffuse networks of discourses and forms of media (2002: 56-57). A queer-identifying counterpublic, in this sense, of necessity includes participants of an alternative public sphere where queer discourses and queer affects circulate and make meaning in and around what Ann Cvetkovich has called "unorthodox archives" shared by its members (2006: 8). [1]

<4> The following synopses of Bugis Street and Bishonen are illustrative of this point, allowing as they do for the concomitant identification of certain essential queer discourses orchestrated by Yonfan himself. Such discourses, I stress, serve as the author's establishing of his affiliations with a queer counterpublic in formation. This first section will be followed by a second part that addresses the ways in which he builds his screen world that, I propose, is marked by queer-coded spatiality, temporality/affect, as well as aesthetics and pleasures. Furthermore, it is my contention that this screen world in sum designates a mise-en-scéne prioritizing queer desires and subjectivities relevant to the Sinophone queer counterpublic. All in all, Yonfan performs his authorship in a queer time and place where members of the Sinophone queer counterpublic find intimate connections and belonging beyond the dominant social institution.

Performing Authorship through Trans-local Queer Discourses

<5> The first full-length feature film out of Singapore to focus on queer subjects, [2] Bugis Street is set in the city-state in the late 1960s. The story unfolds around the life of a naïve sixteen-year-old girl Lian (played by Vietnamese American actress Hiep Thi Le), who comes from Malacca (West Malaysia) to work as a maid at the Sin Sin Hotel along Bugis Street. In short order, she finds out that many of the long-term residents of this budget establishment are "women" born into male bodies. Her first reaction one of great repulsion, she instead decides not to give way to impulse, and she is soon rewarded with the generous friendship from this unorthodox community, particularly from the warm and cajoling Lola (Ernest Seah) and the worldly sophisticate, Drago (credited as Drago).

<6> The most important queer discourse here arises within the colorful transgender culture prior to the historical redevelopment of Bugis Street in the mid-1970s as a modern shopping district-precipitating the eradication of transvestite/transgender activities in the area. As such, gay icons of the time, ranging from Sophia Loren to Zsa Zsa Gabor, to Elizabeth Taylor and her depiction of Cleopatra (dir. Joseph Mankiewicz, 1963), are frequently referred to and imitated. As Bugis Street was produced in the wake of international queer sensations such as Farewell My Concubine (dir. Chen Kaige, 1993) and M. Butterfly (dir. David Cronenberg, 1993), [3] alongside the deep-rooted Orientalist discourse under public scrutiny since the 1980s, the film responds to the Orientalist fantasy with a queer vengeance. In particular, The World of Suzie Wong (dir. Richard Quine, 1960) was referenced in Lian's voiceover with a significant twist: the allusion contradicts audience perceptions of the drama between Lola and an American Caucasian naval officer. Less a generous, romantic lover than a stingy, grumpy patron, the soldier is actually made to pay for his overnight pleasure before he departs the Sin Sin, and what he carries away with him is no better than a grudge. His departure is far from a "sad, touching, loving" farewell between "an American gentleman and a Chinese girl," as Lian relates to her pen pal. This discrepancy in perception arises from queer authorial intervention and injects entrenched Orientalist fantasy with a revisionist sense of the ironic.

<7> Moving north to Hong Kong, Bishonen is set in this former British colony before its 1997 handover, and its tale unfolds around handsome, albeit overly-confident gigolo Jet (Stephen Fung), who happens upon clean-cut, "hunky" policeman Sam (Daniel Wu) and his "girl pal" Kana (Shu Qi). Something of a relationship develops between the two men. Whereas Jet totally falls for Sam, Sam fails to understand and (mis)takes their relationship for "pure," or platonic, friendship; and within this context, he introduces his friend to his parents. Later, it is revealed that Sam had actually been involved with Jet's colleague and roommate Ah-Qing: Ah-Qing had become an escort because Sam had begged him to help repay a debt owed by Sam's then-new boyfriend Kinsley (Terence Yin). The revelation of this secret past triggers Jet's need to confront Sam. Passion ensues, and they are inadvertently seen by Sam's father. Guilt-ridden for having "disappointed" his father, he commits suicide. It is only in this final act that Jet, however heartbroken, comes to understand that he had been "truly loved" by Sam all this time.

|

| Figure 3. Niezi and its English translation as Crystal Boys |

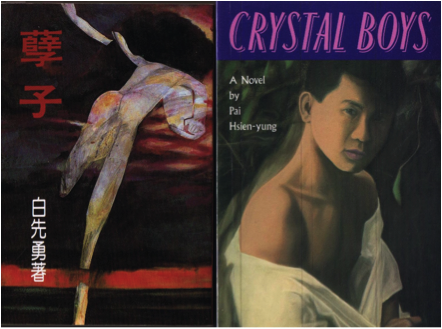

<8> Readily apparent in Bishonen are the traces of influence back to Pai Hsien-yung's novel Niezi ("The unfilial sons," or Crystal Boys), first published in Taiwan in the early 1980s (Figure 3). [4] Arguably the most significant gay novel in modern Chinese literature, Niezi relates the stories of a community of male sex workers and their patrons in and around Taipei's infamous gay hangout, New Park. Central to the narrative is that tension between Ah-Qing's homosexuality and the dominant familial and state ideology.

<9> Certainly, Bishonen shares with Niezi a common focus on male sex workers and on the conflict between gay identity and the Chinese sense of family. Yonfan repositions Pai's earnest old photographer, Grandpa Guo, as a "dirty old man" nicknamed Gucci, and reiterates a real-life scandal involving local policemen who were posing for erotic pictures for a local playboy. [5] The film also pays homage to Niezi in the naming of the somewhat naïve character Ah-Qing, after Pai's innocent protagonist, and by creating Sindy, an effeminate young hustler living on sugar daddies, reminiscent of Little Jade. Similarly, Little Jade's persistent search for his biological father, a Japanese national, acknowledges Taiwan's colonial past in much the same way that Sindy's final departure from Hong Kong for Britain with his English sugar daddy reminds us that the idiosyncratic British colonial legacy in many ways continued to define Hong Kong.

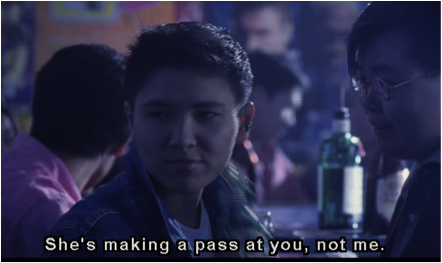

<10> The Japanese element, in fact, pervades the film, notably through Yonfan's appeal to the Japanese queer pop genre "bishonen" (literally beautiful adolescent men) and its romanticized depictions of their homoerotic relationships so prevalent in various Japanese girls' manga and televisual productions (Angles 2011). As Yonfan's take on Niezi through romantic, trendy "boys' love," the film Bishonen also incorporates a crucial reference to the widely popular, queer-coded text, in this instance the "Liang Zhu." In this centuries-old folktale with numerous theatrical and filmic adaptations about unrequited love, Zhu, an upper-class girl who cross-dresses for schooling, falls for Liang, a male schoolmate of humble background. In Bishonen, Ah-Qing compares his love for Sam to that in the maudlin romance involving cross-gender, unreciprocated emotional investment.

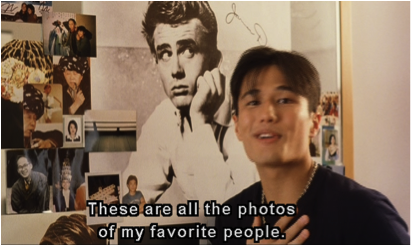

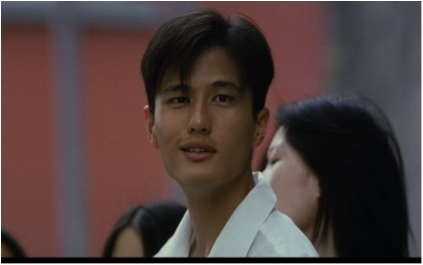

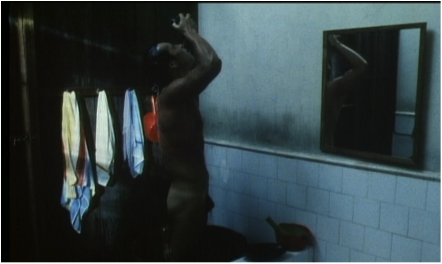

<11> Furthermore, the film "flirts" with a number of gay icons, among them Andy Lau, Leslie Cheung, Aaron Kwok, Richard Gere and James Dean. The character of Sam is in effect a pastiche of young Andy Lau, particularly Lau's screen breakthrough in Ann Hui's Boat People (1981); Kinsley is modeled on the persona of James Dean by way of Leslie Cheung in Wong Kar-wai's Days of Being Wild (1990). Cheung embodies the archetypal young rebel image of "Ah-fei" in Ah-fei zhengzhuan, the original Chinese title of Days of Being Wild, as well as the Chinese translation of Dean's Rebel Without a Cause (dir. Nicholas Ray, 1955). Binding Cheung, Dean, and Kinsley in the larger discourse remains their shared gender-transcending appeal--characteristic of bishonen--and the ambiguity concerning their sexual orientation (Figure 4). [6]

|

Figure 4. Kinsley as James Dean via Leslie Cheung (Yonfan's own portrait is in the bottom left.) |

Staging a Mise-en-scène of Desire for the Sinophone Queer Counterpublic

<12> The "mise-en-scène of desire" made concrete in Yonfan's work remains dependent upon the idea of "fantasy" with respect to subject formation. According to Laplanche and Pontalis (1986: 26) and Žižek (1991: 6), this fantasy is "not the object of desire, but its setting." Through the staging of this setting, "the subject is constituted as desiring" and thus comes into being. Yonfan's mise-en-scène of desire and its corresponding subject positions are not so much heterosexually normalizing as queerly coded with regard to queer space, queer temporality/affect and ultimately queer aesthetics and pleasures.

<13> Queer space can perhaps best be described in terms of the Confucian family-state discourse fundamental to the interpellation of human subjects in Chinese societies in general. On the side of the state, Bugis Street demonstrates an ambivalent attitude towards nationalism. Beyond its overt allusions to The World of Suzie Wong and an anti-Orientalist consciousness, we recognize a poster of Bruce Lee prominently displayed; in fact, a sense of anti-Orientalism is embodied and reverberates through the anti-colonialist message that defined Lee's screen persona (Figure 5). [7]

<14> It needs be mentioned at this point that the "queens" of the Sin Sin Hotel possess something akin to a nostalgic longing for the colonial heritage-hence, the central placement of the portrait of the British Queen in Lola's room (Figure 6). This ambivalence toward colonialism, I suggest, is itself a reflection of the local queers reservation about proactive nationalism. Indeed, there is curious lack of any mention of Singapore's newly acquired independence; rather, as the film's final scene records, state-sponsored urban redevelopment, along with the crackdown on queer lifestyles in the name of nation-building, looms large. The surrounding high-rises in the background suggest as much. What Bugis Street represents, then, is a colorful era in the history of the region felled before the development of the nation. In a similar manner, Bishonen shows no clear sense of nation. Neither are there signs of celebration of Hong Kong's handover. In their stead, we are left with Sam's suicide and the passing of romance, "symptomatic" of what local queers had envisioned of their future after China's takeover.

|

|

| Figures 5 and 6. Bruce Lee poster and a British Queen in the backgrounds | |

<15> Equally powerful, depictions of family are characterized by a structural absence of "happy" or "complete" heterosexual families. In Bugis Street, for instance, Lian remains an orphan who grew up as a servant in her master's residence, the transgender women of the Sin Sin Hotel exist without connection to their biological families, and even the sophisticated Drago, who returns to Singapore to visit her hospitalized mother, has been reared single-handedly by her mother. Her passing only marks the continuation of Drago's journey overseas.

<16> Given its portrayal of a "wholesome" family, Bishonen appears at first glance to be an exception to Yonfan's overall philosophy of filmmaking. Sam and his loving parents comprise a nuclear family certainly, but it is a family caught in transition from completion to incompletion with the son's suicide. Tellingly, for a large part of the film, Sam introduces Jet as his close friend, and the four enjoy their time together as if they were one "happy family." But the scenario serves as no more than dress rehearsal for an imagined moment in time when a son and his lover are wholeheartedly embraced by the parents. When the son is revealed to be gay and his close friend unveiled as his lover, this idealized picture shatters. The tragic turn of the narrative, in effect, foregrounds the perceived incompatibility between homosexuality and the Chinese family unit, wherein the mandate of filial piety and the son's responsibility to continue the family line are alien. This incompatibility, I believe, is key to understanding why Yonfan, as a gay-identifying artist, holds such a cynical view of the heterosexual family and why the structural absence of happy, complete heterosexual families in his overall filmography.

<17> The perceived incompatibility between homosexuality and Chinese family--the latter aligned with the dominant filial piety-loyalty nexus and family-state discourse, further informs the compressed living space for queer subjects, in particular their mixed feelings toward the sense of belonging. Belonging, or the lack thereof, underpins the crucial foundation of the imaginary of Chinese queer diaspora (Chao 2013). By Chinese queer diaspora, I mean the kind of dislocation that is figured through being queer in Chinese cultural settings, involving emotional and physical terms certainly, as it manifests in both internal and external exiles. Here I have used Bugis Street and Bishonen to exemplify the tension between the characters, the nations and the heterosexual families that they supposedly belong to. It is these characters, to a large extent, who inhabit the spatial configuration of Chinese queer diaspora.

<18> Meanwhile, the seemingly unresolvable complex between homosexuality and the Chinese family unit is laden with temporal and affective ramifications, ostensibly comprising the second aspect of the "mise-en-scéne of desire" in Yonfan's work. I find his films as characterized by a sense of loss and melancholy. Bugis Street, for example, can be understood as a coming-of-age story of protagonist Lian, although that process also comes with her falling in and out of love with a teenage boy in an unexpressed (if not "unspeakable") fashion. Lian's transgender friend Lola, by the end, breaks up with her long-term, abusive boyfriend, and Drago has to deal with the passing of her beloved mother. To be sure, the film itself is about the times lost in the wake of historical progress. In Bishonen, Sam's "departure" is in fact indicated in the prelude by the disembodied, goddess-like voiceover (performed by Brigitte Lin, a superstar of 1970s romantic melodramas who would revitalize her career in the 1990s with androgynous martial arts characters as in "Asia the Invincible" in the Swordsman series). The entirety of the film is given its structure by melancholy. As an unresolved grief involving a continuous engagement with loss and its remains, melancholy, in psychoanalytic terms, is essentially a pathological mourning without end (Freud 1989: 584-589).

<19> From a sociological perspective, gay melancholy, arguably, is foremost configured by the rejection of heteronormative values and ways of life. It is for gay-identified subjects an unending mourning of "ways of life and forms of relations to others that have been set aside or done without, willingly or not, because of their sexuality" (Eribon 2004: 37). Central to this structure of feeling is "the loss of family ties" (2004: 37). It should be noted that such family ties in Chinese societies not only implicate the parents, the siblings, and the family circle mentioned by Eribon. But they also indicate the social network and an individual's subject position centered upon the family unit. Gay identification in a Chinese society, accordingly, is imbricated in the bitter negotiation between an avowed expression of personal desire and identity and affirmed position of the individual in the family-based, heteronormative social institution. While a person's pursuit of a gay identity often puts at risk his/her family, familial ties and social position, for a gay person to secure family ties and social position likewise means to compromise to varying degrees personal desire and self-identity at precisely the same time. This bitter negotiation or trade-off, therefore, affects that sense of loss integral to queer subject formation. In Yonfan's case, the fact that his characters-queer and otherwise-are haunted by a sense of loss and his films, marked by a melancholic structure, I suggest, has much to do with the gay melancholy configuring Yonfan's own queer subjectivity.

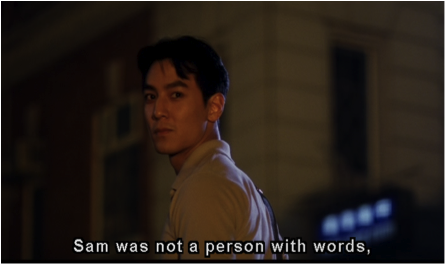

<20> Symptomatic of this melancholy, Yonfan's obsession with the lost objects and the past also finds expressions by less direct means. For instance, there are photographers, cameras, photos, and the plot of photo shoots in each of Yonfan's feature films. Very often, slow-motion cinematography is also employed-sometimes combined with the act of photo-taking-to emphasize certain memorable moments for the involved characters. As the narrative progress inevitably leaves these moments behind, the photos would serve as the anchor of the characters' memories, while the slow-motion cinematography renders explicit the characters' desire for holding onto those personal, ephemeral moments from the past. Corresponding to his use of photography and slow-motion cinematography, Yonfan notably demonstrates a penchant for images wherein characters turn around or look back. Bishonen, in particular, features an array of backward glances, all largely motivated by homoeroticism (Figures 7-16). All this slowing down and looking back, I stress, gives rise to a tension with the heteronormative temporality underlined by reproduction, progress and efficiency. Imbricated, drunk on gay melancholy, Yonfan's obsession with the past and the "would-be lost" objects, to a certain degree, leads ultimately to a counterforce to what Lee Edelman has termed "reproductive futurism" that prevails heteronormative societies (2007).

|

|

| Figure 7 and 8. Jet's backward glances | |

|

|

| Figure 9 and 10. Kinsley's backward glances at Ah-Qing and Sam, respectively | |

|

|

| Figures 11 and 12. Kinsley's backward glance at Sam, and Sam's at Jet, respectively | |

|

|

|

|

| Figures 13 to 16. Sam's posthumous farewell in Jet's dream | |

<21>The third aspect of the mise-en-scène of queer desire, namely queer aesthetics and pleasures, refers to the gender-bending camp aesthetics operating against heteronormative gender conventions and erotic economy. In Bugis Street, for instance, there are numerous major and minor roles performed by real-life transgender subjects. In Bishonen, we likewise find a parade of "sissies," including Sindy, two patrons of Jet, a stranger pretending to be Sam in response to Jet's newspaper advertisement, and the lusty middle-aged photographer Gucci. Importantly, no matter how minor their roles are, each of these gender nonconforming characters confidently live their lives as tangible, desiring subjects. A scene in Bugis Street, for example, not only shows the agency of Lian but also that of Drago through their active gaze on a half-naked male gardener; Yonfan's shot/reverse-shot and eye-line match techniques, notably, only reaffirm that Drago's queer agency is to be rewarded by her object of desire (Figures 17-19). Equally fascinating in Bishonen is the androgynous style of Kana at a nightclub (Figures 20-25), which, through Yonfan's editing, stages "a triangular relay of gazes" between Kana, Jet, and a lesbian butch and involves a "bisexual spectatorship" (Leung 2008: 21) mediated by the lesbian butch-femme erotic economy (Case 1988-89: 55-73). Gender nonconforming characters in a sense invite their audiences to partake in alternative viewing positions and alternative pleasures.

<22> Interestingly enough, all of Yonfan's films also incorporate segments hinged upon a patently erotic gaze on male bodies. In many cases, the look is not even initiated by female characters. Two of the male shower scenes in Bugis Street, for instance, are either unanchored (Figure 26) or anchored by transgender women (Figures 27-28). Even if the look is initiated by a female character, the prolonged gaze often transcends the character's point of view. It floats around and moves closer, providing the non-straight male audiences with access to (homo)erotic fantasies and pleasures. [8] Yonfan's work, in other words, deviates from the heterosexual normative paradigm of spectatorship centering on the so-called "male gaze." It corresponds to and vividly animates a kind of mise-en-scéne prioritizing queer desires and subjects.

|

|

| Figure 17. Drago and Lian look at a man. | Figure 18. The man looks at Drago. |

|

|

| Figure 19. A reverse shot connects Drago | Figure 20. An androgynous Kana initiates a look |

|

|

| Figure 21. …at Jet | Figure 22. …and |

|

|

| Figure 23. a lesbian butch… | Figure 24. that privileges… |

|

|

| Figure 25. …lesbian butch-femme dynamic | Figure 26. An unanchored gaze at male nudity, his penis only partially visible. |

|

|

| Figures 27-28. A scene of male nudity in association with the voyeuristic gaze of two transgender women | |

<23> When taken together, Yonfan's work privileges non-normative subject positions foundational to the queer counterpublic who participate in the alternative public sphere where queer-coded discourses and affects circulate and make meaning. The significance of Yonfan's queer authorship, along with the author's queer agency, I maintain, lies in its intention to engage the queer counterpublic in imaginary dialogues. By means of the queer discourses and affects in circulation in the alternative public sphere they share, Yonfan establishes intimate bonds with the Sinophone queer counterpublic; with his continuing audio-visual output, he enriches and helps expand the queer cultural archive in a transnational framework. All in all, Yonfan performs his authorship in a queer time and place where members of the Sinophone queer counterpublic establish intimate connections and belonging beyond the heteronormative social institution.

Principal Cast and Crew of Bugis Street (1995)

Director: Yonfan

Writers: Fruit Chan, You Chan and Yonfan

Lian (Hiep Thi Le)

Drago (Drago)

Lola (Ernest Seah)

Drago's Boyfriend (Kelvin Lua)

Principal Cast and Crew of Bishonen (1998)

Director: Yonfan

Writer: Yonfan

Jet (Stephen Fung)

Sam Fai (Daniel Wu)

Kana (Qi Shu)

Kinsley (Terence Yin)

Ah-Qing (Jason Tsang)

Sam's Father (Kenneth Tsang)

Sam's Mother (Chiao Chiao)

Gucci (Joe Junior)

Acknowledgement: Unless otherwise noted, all images were acquired under a Creative Commons license.

Notes

[1] These unorthodox archives feature "cultural texts as repositories of feelings and emotions, which are encoded not only in the content of the texts themselves but in the practices that surround their production and reception" (Cvetkovich 2006: 7).

[2] In her introduction to a recent anthology, Queer Singapore, Audrey Yue delineates the constraints and difficult processes of local queer culture mediated by the dominant "illiberal pragmatics" (2012: 1-25). For a discussion of queer imagery vis-à-vis "illiberal pragmatism" in Singapore cinema, see Chan (2012: 161-174).

[3] Yonfan mentions certain connections between Farewell My Concubine, M. Butterfly, and (to a lesser extent) his Bugis Street by way of his friendship with John Lone (2012: 139-147), the lead actor in The Last Emperor (dir. Bernardo Burtolucci, 1987) and M. Butterfly (dir. David Cronenberg, 1993). For a discussion of M. Butterfly, its intertextuality and the Orientalist legacy, see Chow (1998: 74-97) and Eng (2001: 137-166).

[4] To be more accurate, Bishonen is based on a novella titled Zhongnan wan-meishaonian zhi jing lian, written by Yonfan himself. Traces of the influence from Pai's Niezi are equally evident in his novella (Yonfan, 1998: 64-89).

[5] "Chailao yin zhao jie." Pingguo ribao.

[6] Leslie Cheung's sexual orientation remained somewhat ambiguous until he officially came out in 1997.

[7] Admittedly, the appearance of Bruce Lee's poster here is anachronistic, in that Bugis Street is supposedly set a few years prior to Lee's having achieved international stardom in the early 1970s. In particular, the poster from Enter the Dragon is inscribed with the year 1973. For a discussion of Bruce Lee's screen persona, see Berry and Farquhar (2006: 196-204).

[8] This is best exemplified by the shower scene in Peony Pavilion that runs over two minutes. Featuring Daniel Wu's masculine physique, the scene is initiated by the presence of Joey Wong's character, but it soon breaks free from the character's particular voyeuristic viewpoint.

Works Cited

Angles, Jeffrey. Writing the Love of Boys: Origins of Bishonen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Berry, Chris, and Mary Farquhar. China on Screen: Cinema and Nation. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2006. Pp. 196-204.

Case, Ellen-Sue. "Toward a Butch-Femme Aesthetic." Discourse 2.1 (1988-89): 55-73.

"Chailao yin zhao jie," Pingguo ribao. http://hk.apple.nextmedia.com.

Chan, Kenneth. "Impossible Presence: Toward a Queer Singapore Cinema." In Audrey Yue and Jun Zubillaga-Pow (Eds.), Queer Singapore: Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012. Pp. 161-174.

Chao, Shi-Yan. Processing Tongzhi Imaginaries: Chinese Queer Representation in the Global Mediascape. New York, NY: Department of Cinema Studies, New York University, 2013.

Chow, Rey. "The Dream of the Butterfly." Ethics after Idealism: Theory-Culture-Ethnicity-Reading. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1998. Pp. 74-97.

Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Dyer, Richard. "Believing in Fairies: The Author and The Homosexual." In Diana Fuss (Ed.), Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories. New York, NY: Routledge, 1991. Pp. 185-201.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

Eng, David L. "Heterosexuality in the Face of Whiteness: Divided Belief in M. Butterfly." Racial Castration: Managing Masculinity in Asian America. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001. Pp. 137-166.

Eribon, Didier. Insult and the Making of the Gay Self. Trans. Michael Lucey. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

Freud, Sigmund. "Mourning and Melancholy." In Peter Gay (Ed.), The Freud Reader. New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company, Inc., 1989. Pp. 584-589.

Laplanche, Jean, and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis. "Fantasy and the Origins of Sexuality." In Victor Burgin, James Donald and Cora Kaplan (Eds.), Formations of Fantasy. New York, NY: Routledge, 1986. Pp. 5-34.

Leung, Helen Hok-Sze. Undercurrents: Queer Culture and Postcolonial Hong Kong. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008.

Stam, Robert. Subversive Pleasures: Bakhtin, Cultural Criticism, and Film. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

Warner, Michael. "Public and Private." Publics and Counterpublics. New York, NY: Zone Books, 2002.

Yonfan. "Zhongnan wan," Lianhe wenxue 14.9 (July 1998): 64-89.

---. Yonfan shijian/Intermission. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Yue, Andrey. "Queer Singapore: A Critical Introduction." In Audrey Yue and Jun Zubillaga-Pow (Eds.), Queer Singapore: Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012. Pp. 1-25.

Žižek, Slavoj. Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991.

Return to Top»