Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 2

Return to Contents»

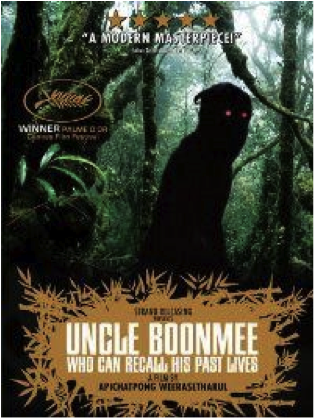

Weerasethakul, Apichatpong, Dir. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. 2010. Film / Kenneth Dobson

<1> Winner of the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival in May, 2010, and directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul (b. 1970), [1] Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (ลุงบุญมีระลึกชาติ Loong Boonmee raleuk chat, 2010) is a Thai film designed to conceal or to reveal. It must be one more than the other, never both in equal measure, and this precarious nature has led to confusion and, at times, disdain or dismissal by critics. Some, especially reviewers from Los Angeles, focus on political innuendos and allusions; the readings are not unjustified, given that the director's previous films in the series (this film is the final installment), as well as his own comments, tend to support such an interpretation. But to conclude that Uncle Boonmee is little more than a thinly veiled rumination on racism and essential human dignity, on the manner by which the Thai government routinely eradicates opposition and revises history, or on the deaths of innocent people during the anti-communist campaigns is perhaps unwarranted. In point of fact, this film is constructed as an artistic montage in which various Thai styles from comic books to old-style films comprise a sequence of images wherein the lines between realms of real and irreal conspicuously blur.

<2> At the conclusion of the work, Apichatpong informs his international audience that there, in truth, had once been a man in Isan who had told a monk that he could recall his past lives. These recollections were compiled into a book that became the impetus (but not entirely the basis) for this movie, made some two decades or so later. His remarks harken back to the first scene in which the director has explained that past lives might have taken the form of animal or human being. Of course, a Thai audience would have recognized as much and would have readily recognized that such past lives weave the sequence of images together, even as they signify how all is in transition, simultaneously passing away and coming into being. How very Thai it is to have the lines between the mystical and the natural remain intentionally ambiguous.

<3> Uncle Boonmee, a former soldier, is dying of kidney failure. Having established a plantation of tamarind and other fruit trees using migrant laborers, he invites his sister-in-law Jen to return and acquaint herself with the farm since it will be hers when he soon dies. It is his wish that she maintain it and pass it on to her daughters. His sister has also returned with her grown son Toong. Over a nighttime meal, they are joined by the ghost of Huay, Boonmee's former wife and his sister-in-law's sister. Although she has materializen and taken on her previous physical form, she does without food or sleep and can disappear and reappear at will. He asks whether she has come to spirit him away; and when she does not reply, Thai viewers immediately assume that she has. Also present is a "monkey ghost" who turns out to be the incarnation of Boonsong, a son who has died while trying to photograph ghost-monkeys in the forest. He informs Boonmee that animals and spirits alike are aware that he will soon be joining them. Boonmee remains unconcerned.

<4> Later, in the context of a dream, we see a Khmer princess carried through a forest on a litter. Attracted to one of the handsome litter bearers, she invites him to join her alongside a pond and waterfall. While there, however, she sees a reflection in the water of a face as she used to be, young and beautiful (her face is now deformed, and she is old and filled with self-doubts). Wishing to entice the young man to make love to her, she is overwhelmed; fearing that he might not see her as she was, she instead dismisses him. Thereupon the "Lord of the Water," having assumed the form of a catfish, speaks. She contrives to substitute him as her would-be lover, and she casts her gold jewelry into the water as an offering. The fish collects the gold, before performing cunnilingus on her, and steals her away from a life on land where she is no longer who she wants to be.

<5> Almost certainly this scenario is one of Boonmee's recollections of a past life, but it is less certain whether he is the princess, the litter bearer or the catfish. Nevertheless, the scene involves not only a transition for the princess but also one for Boonmee, who suspects that his present condition is the karmic consequence of his having earlier killed while serving as a soldier.

<6> Finally, as death approaches, Boonmee empties his pockets and invites Jen and Toong to accompany him on his final walk through the woods, on one level at least a liminal, transitional or threshold space. They begin their arduous hike toward the cave-arduous for all, save his ghostly wife who has taken the lead. At a distance, monkey ghosts fill the trees. As they arrive at their destination, Boonmee observes that the cave, dark, is similar to the womb and that he has completed this cycle of life. Huay disconnects the shunt from his kidneys and drains his body of life fluids. Boonsong and the other monkey ghosts wait for him to join them.

<7> But as this scenario comes to an end, no film credits roll. Instead, a funeral and a twist in plot remain.

<8> Most non-Thai reviewers fail to appreciate just how very ordinary this funeral is. Native viewers readily recognize an Isan Buddhist funeral wherein the dutiful male heir is ordained as a monk to gain merit in behalf of the deceased, where the relatives take charge and priests chant, and where the casket is adorned with blinking lights and flowers. Be that as it may, the ceremony, wholly different in color and light, is the antithesis of the unadulterated natural world of the forest and its chorus of insects and winds rustling through the leaves.

<9> And while it is Boonmee's funeral, this transition we witness is about not Boonmee. Nor is it about Jen. Absent is the liminal forest. The film meanders, leaving us uncertain what is going on and what is left to be said-until we overhear a knock on the door of a hotel room where Jen and her daughter have set about recording contributions received from those in attendance at the funeral. Toong asks to come in, still dressed in his monk's saffron robes; Jen reluctantly admits him, while emphasizing the inappropriateness of a monk present in a hotel room with women, whether they be close relatives or not.

<10> Toong explains that he has not slept; the temple is too quiet, he has overheard Boonmee and someone talking in the distance, and he is in sore need of distraction, television or the Internet, for example, perhaps a hot shower. Some have gone so far as to suggest that the film provided the vehicle wherein the director could make a show of his boyfriend (who played the role of Toong). After his bath, Toong dresses in his street clothes, and with an air of finality he folds his robe. Recognizing that he has broken with Buddhist tradition and invalidated any act of merit in getting ordained, Jen suggest to him that there might be another time to accrue merit. In a final breech of a monks' vows, Toong takes food during the second half of the day. Disturbed by the senseless violence in a military maneuver being replayed on the television news, Toong and Jen simultaneously rise to leave and, wholly captivated and in shock, remain on the edge of the bed. We realize, however, that they are neither fully committed and entirely present in any one place: while in the noisy night spot, they are strangely placid; in the hotel room, their doubles remain eerily still.

<11> Their precarious positioning goes unresolved as the credits roll. And that is the prevailing sense among viewers as they depart.

<12> Some might argue that, had this film been little more than a composite of sequential coded messages concealing layers of multiple meanings, it would never have taken the Golden Palms Award at Cannes. Nor would it have passed the scrutiny of the Thai Culture Ministry's censors (who had repeatedly edited and revised Apichatpong's previous works). Within this light, the film accurately reflects the prevailing Thai view of the indefinite interface between the natural and the mysterious, serenity in the wake of violence, of transitions and impermanence, reincarnation and karma, as well as the natural place of death as a part of the cycle of life.

<13> Apichatpong goes so far as to suggest that, by splicing different types of film, his work becomes a tribute to a passing part of authentic film culture, as the use of the 16 mm reel gives way to the digital.

<14> But it is the poetic nature of this work, with its slow pace and the accompanying sense of meditative lingering, that suggests the important place of revelation, and in fact the audience, whether Thai or otherwise, must be involved and active in the process of viewing in order to apprehend all that happens to them. They have been moved. The film opens with a water buffalo's wanting to be free; it ends with the image of a young man who, unable to endure a serene and peaceable life after having been ordained, seeks out the flashy comforts promised modern civilization and the imminent violence already so familiar.

Principle Cast and Crew

Director: Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Writers: Phra Sripariyattiweti and Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Uncle Boonmee (Thanapat Saisaymar) (

Jen (Jenjira Pongpas)

Toong (Sakda Kaewbuadee)

Huay (Natthakarn Aphaiwond)

Boonsong (Geerasak Kulhong)

Acknowledgement: Unless otherwise noted, all images were acquired under a Creative Commons license.

Notes

[1] As a central figure in contemporary film and art, Apichatpong Weerasethakul employs a singular realist-surrealist style, portraying as a matter of fact the quotidian alongside supernatural elements and suggesting a distortion between fact and folklore, the subconscious and the exposed and various disparities of power. His work reveals stories often excluded in history in and out of Thailand: voices of the poor and the ill, marginalized beings, and those silenced and censored for personal and political reasons.

Return to Top»