Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 2

Return to Contents»

Habitats for Whom or What: Barney Cheng's Baby Steps (2015), Affect Politics and Transgender Bodily "Housing" / Lucifer Hung

Abstract

This paper proposes a queer reading against normalized imagination of "residence (as) rights" based absolutely on property ownership and hetero‐reproductive familial narrative. My argument will build upon the event of "Clan Wang's ancestors' house being demolished by [a] heartless government" from March, 2012, to trace the condition in which Taiwan's land mass (especially those in urban areas) has increasingly become a post‐capitalism' pawn, handled ruthlessly together by cooperation, the state apparatus and legal/governing system. What I am most concerned with is less the non‐normative, even recalcitrant possibility of intervention into the rights discourse and rhetoric of the norm, which argues for "living in a certain place" as non‐given and non‐naturalized modes of being. Instead, I provide a critical re‐reading of citizenship, be it the middle class, imagined or otherwise. On the one hand, these battles give rise to innovative lifestyles and the possible coalition among different gender/sexual positions; on the other hand, however, we need confront the re‐imagined "traditional" heteronormative way of life celebrated by and inscribed in, sarcastically, at least partially as the agenda of LGBTQ defenders of family and home to treat "having a home" as the final frontier and last signifier of a livable subject‐position.

Keywords: home, citizenship, legitimate property rights, Baby Steps

<1> I neither oppose nor defend the proposition that Wang's house must remain on its original site and built back to what it was; for what I deem as far more pressing is a queer querying position sustained and denied by rightful ownership and its hetero‐familial system that dominates most expressions of anti‐relocation ideology. Based on "decent family's right to live in their original owned property," this politics of pro‐residence rights inevitably supports only certain spatiotemporal structures of residences and, as it does so, further bolsters the normal familial‐reproductive paradigm. Such a contention de‐historically and in a one‐dimensional manner argues for the likes of private property, longevity, behaved and stable heterosexual life, modest citizenship, patriarchal structure of inheritance and Consanguinity (assuring the paternal blood ties continuity in its biologically correct format).

<2> Moreover, the powerful, fixated imagination need establish itself through the exclusion of the many forms and realities of residence, among them sexual and economic minorities, abject subjects, people who could not or would not have access to the ownership of property. Within the frame of the normalized polemic of residence, the urban familial way of life empowers itself by disavowing (and treating as disposable) those who refuse to accommodate themselves within the linear and teleological order, those who have already lived a complex and productive "penumbra" multitude outside or beyond the limit (or liminal boundary) of hetero‐ and homo‐normativity.

No "Natural" (Rights of) Residence

<3> There are many complicated subject positions complicating issues of urban renewal. As participants within the larger debate, their positions are far more multilayered and ambivalent than those occupying

1) state apparatus and its helpmates,

2) capitalistic cooperation,

3) owners who agree to relocate, and

4) owners who refuses to negotiate with the aforementioned parties.

At first glance, Wang's refusal to relocate appears a struggle between middle or upper‐class land owner and their counterparts. As we read closely the narratives of the various sides and their propagandas contextually, however, we must not overlook those voices, defending or rejecting one peculiar land owner's private property, that represent and speak for the dispossessed, the poor and the marginalized (non) owners of bodies and its shells.

<4> Focusing on the protection of Wang's household rights, the defensive camp is comprised of scholars (mostly in law and the humanities), research and undergraduate students, "ordinary" people who empathize with this action via a collective "decent citizenship" and more specifically those who jealously guard their ownership of land or residence. Curiously however, among such members are people who either are already "homeless," marginalized as they are by gender/orientation/sexual practices or who exist in such a manner that others deem them as undeserving of a "permanent home," among them the unruly youth outside the realm of biological kinship and professional, yet economically under‐compensated social activists. The latter category situates a wanton subcultural defiant rage within this residence battleground, but its voice, along with its plural anti‐normal subjectivity, is least heard both by the mainstream media and by citizen supporters. Even as I write, there is-and was-little media attention given to intriguing discourses on the (non)‐relational affinity between sex/gender outlaws and the normative ideology of residence. Yet to emerge is a non‐realist imagination within the dominant discourse that rejects "fantasmic" living subjects and their unapologetic way of living (and of claiming territories). I analyze this dynamic within a queer theoretic framework to articulate unbending nature of "queer time and queer space" and its incompatibility with the normative supporting reproductive familial logic.

<5> Certainly, the article, "Is There Necessary Justification to Unconditionally Support Wang as Land‐owner?" has generated furious and

indignant response. The static and stereotypical imaginations on gender and sexuality as being reproductive‐oriented assumes that the

contract‐holder within the family is the patriarch of the Wang clan and that other members do not enjoy the equal guarantee of ownership. Were we

to imagine, for example, an offspring or non‐consanguine female spouse being removed from the household by divorce or through

renouncement/rejection by the paternal power, it follows easily that such individuals, as they move from one space to another as Wang's authentic

member to the unrelated, are simultaneously dispossessed. Even within the reticent and redolent ideology supporting filial doctrine, the oldest Wang

member, the aunt of the patriarch Wang, does not "own" either the household or does not have "access" to its economic resource.

<6>In fact, it is ludicrous to consider the entire Wang family as landlords. The cold truth is that the position as landlord can only be occupied by one adult male in the Wang family who actually holds contract. Any claims of "We don't need money" and "All we want is family warmth" betray larger truths about class that necessarily make the antisocial queer community shudder. We know that any professed indifference to money literally means "sufficient balance in the bank account," and "wanting nothing but 'warmth,'" that all other desires and rights are already satisfied. The former slogan is an obvious insult to residents who actually do need (or who are now forced into a position where they need) money: those less affluent or less fortunate require money in order to survive and would likely exchange long‐term property rights for the immediacy of cash. The latter slogan is far worse-the scenario of "loving parents/obedient children/permanent property" implicit to the term "warmth" fundamentally excludes subjectivities that cannot/do not otherwise procreate, marry and, in keeping with this logic, own property.

<7> Furthermore, even were the image of "the one who possesses" under the objective of normative residence rights, to have been somehow extended beyond the limits of traditional patriarchy and the petite‐bourgeois nuclear family to include "gay and lesbian" subjects, the extension the would not be without qualification. As suitable subjects, they would need pass (through) cultural, social, generational, class, erotic, bodily, economic and positional tests/rites in order to participate in what is no better than a patronizing system of distribution supported by a gay rights movement complicit with the state. In terms of affective/sexual relationships, (trans‐) gender bodies, and (quasi‐) family structures, current residence rights cannot possibly extend an affable hand to queer subjects in the absence of rigorous and severe qualification. Perhaps somewhat more preferable, resident subjects, queer or straight, need been included within the machinations of the state apparatus and thereby eligible to obtain residence under the empty slogan, "everyone has the right to residence" (in practice, the "everyone" here does not actually refer to all "naturally born" citizens as such). In circumstances where queer positions are criticized (usually out of "benign" political correctness), the contextual reasons for exclusion from the proud gay collectives rely upon their steadfast resistance to the static permanence that the family, the normalizing consistency of gender and the body, and the social and hierarchical compatibility between sexual/intimate partners. [1]

<8> These qualifications explain why queer genders/bodies/forms of residence are fundamentally incompatible with the kind of "liberal" "pluralist" concepts defining intimate relationships, gender identities and politics and family structures that normative LGBTQ movements endorse. Without a radical revision to how we imagine existing residence rights, intimate relationships, gendered bodies, and the family (along with its modes of being), it remains impossible for queer lives to "rise above" and exist alongside gender‐normative citizens who seemingly are possessed with more rights of residence "Others." What is worse, any stance that allows the premise that queer lives constitute an abject wasteland of bodies, desires and relationships necessarily relegates the queer as scapegoats to be exorcised both by liberals and moralists. Such discussions make room for a potential Leftist identification with non‐property owners (intentional or unintentional), sex radicals and gender outlaws and supporters of radical residence rights. Our current agenda, then, is not only to resist the capitalist state machine but also to challenge the kind of sentimental rhetoric normative anti‐urban renewal movements embrace. We need to consider how to confront arguments of "static permanence" that advocate, both biologically and symbolically, the fantasy of immortal serenity-a matryoshka doll‐like infinity that can never be actualized in reality-through generation after generation of breeding and rearing offspring, ad infinitum ad nauseum, just the kind of apolitical/de‐politicalized, individualist rhetoric that advertises the promulgation of heteronormative families.

<9> As to how certain new intimacies and non‐normative residence forms interpret, compare and mutually reflect each other, we can take cues from several forms of unruly life in the following events and autobiographical accounts that bear witness that queer lives have always existed but underscore that must now be compelled to emerge from a nascent presence. Leslie Feinberg's Stone Butch Blues and Drag King Dreams recovers stories of Jewish "stone butches" in the latter half of the twentieth century who vacillate between male and female presence while identifying with neither. Put differently, these tales reiterate queer lives who have no residence rights and who are thereby perpetually expelled from habitats (towns and houses of their biological families, for example), sexual relationships and the "correct and standard" body politics demanding that everyone must (and only) live in a permanent and normal body.

Queer Perspective in Reading Body as Non‐or‐Plural Residence Site

<10> Recently, transgender queer theorist Jack J. Halberstam has posted an article, "On Pronouns," on the front page of his website. He addresses the incessant bombardment from beyond that questions identity and requiring the selection of a fixed gender pronoun (that is, to take sides between the normative "he" and "she" without any noticeable lacuna, obscurities or sense of ambivalence). The body, considered a residence of subjectivity (i.e., the body's positionality), avoids relocating, occupying and living without a contract. Moreover, were residents already to occupy a "higher" sociocultural rank, they be advised to find "a nice house" (body) and purchase the surgically modified body/house that is either male or female. As queer residents, they are cautioned against lingering between non‐normative places/bodies and marginal foundations/anatomies while flaunting the appearance of the(ir) broken, patched and undesirable houses/physical presence. Halberstam exposes how emissaries of (limited) transgender rights appropriate the rhetoric of reticence to encourage a kind of normalized transgenderism (comparable, I believe, to proudly bleached lesbians and gays). These missionaries are therefore confounded, even infuriated, by his recalcitrant insistence against the "she or he" mantra. Instead, multiple bodies form a plural residence difficult to interpret and painful or nearly impossible to recruit by normative gender proponents—and the so‐called liberal gay mainstream. Although the rich and complex texture of this plural habitation deserves careful preservation, in reality it is often allegorically and literally considered an "illegal residence."

<11> For current non‐normative residence rights groups and their differing factions, concerns, and believes, my participation is both riddled with reservations and adaptable to tactics of circumstances. I am open to collaborations (with conditions) with the petite bourgeois, but I believe that cultivating the theories and practices of property‐less residence during the collaborating experience is of far more urgency. I believe that neither the Left nor the non‐Left wishes to see residence rights movements degrade, devolve into no more than a weapon for land and property owners to evacuate non‐owners. I hope that collaboration between different factions and political proclivities might lend itself to discourse of queer (negative, property‐less, anti‐success) residence rights, of necessity through the careful negotiation of tactics. How should we disturb and dismantle the "protect the family" rhetoric that promotes an image of the "warm" heteronormative-read that as "large"-family (as such oft‐heard phrases, "housing six generations" and "heritage of five generations," for example, illustrate) without being misunderstood as an act of envy by abnormal subjects? Just as Xiang Hong‐yen argues in "Mapping Diaspora: An Investigation of Residence Issues," unfair distribution of residential housing to subjects (or collective subjects) is the overt expression of oppression, surveillance and exploitation of (non‐bourgeois) workers and non‐property owners.

<12> Many non‐normative scholars/students who are on the front line of the anti‐urban renewal movements intentionally or unintentionally, however, avoid these questions; some even consider them impractical. I believe that Zang's observations lay bare internal contradictions of the movement, as he forthrightly claims that current anti‐urban renewal discourses would only lead to a protection of the rights of those who already have them (people who have secured land and housing but who are in some way threatened to relocate). The Wang household represents middle‐class landowners, but the less affluent Peng household in the Yong‐chun urban renewal case was not spared the same middle‐class discourses adopted in the petitions. Advocates for their rights adopted a rhetoric completely irrelevant to non‐property owners, queers and the outcasts stripped of familial heritage included. This blindness and indifference to outcast positions is described thusly:

At seventy‐seven, Mr. Peng fixes motorbikes with his right hand, while his left hand is left paralyzed. On the eve of the final hearing, he was working while remembering that his 21 ping Motorbike shop would be reduced to 15 ping. Three generations of the Peng household depend on the shop-how will they survive without the business?

<13> Arguing from the perspective of queer critical social movements, I suggest that any non‐normative subjects supporting "existing equals residing" should immediately forgo their silence (if they have done so in the fear of disturbing the integrity of the movement). We (the positions and subjectivities including myself) ought to propose several critical strategies against the discourses defending a‐temporality, multi‐generational housing and the "warmth of family" (the term "family" being inclusive only of heterosexual and patriarchal heritages and the nuclear family). Appropriate strategies should be directed toward

In terms of many complex metaphors and associations that treat residence (rights) as seemingly synonym with body rights (among them the Abrahamic mandate equating body with sacred temple, in recent turns in gender politics, the body as one's very sovereignty and sacred site of autonomy confronting to tremendous challenges within the propagandistic contexts of marriage equality.1) the capitalist state machines,

2) the middle‐class/landowning class that cares only about their ownership of properties,

3) the fantasy of a (both symbolic and material) "household" that permits only the monogamous, paternal heritage, and

4) the "proud" gay and lesbian subjects who attempt to squeeze into normative positions while being indifferent to both historical contexts and the abject queers that have become the residue of their pride.

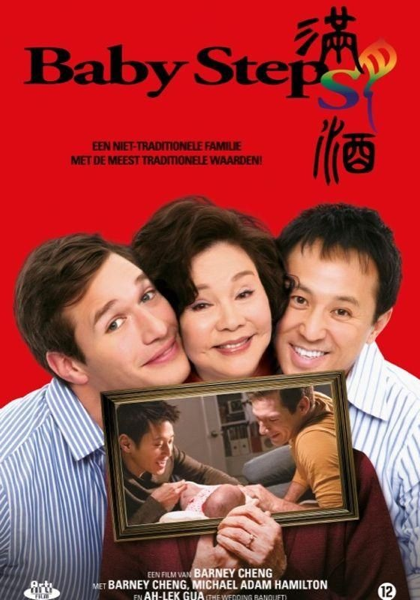

<14> One such striking cultural and political representations found within the Chinese cinematic industries is the LGBTQ self‐celebrating

film Baby Steps (滿月酒 Manyue Jie, 2015).

Figure 1: Film Poster

<15> This film addresses the problematic of gender, race, and sexuality within the frame of gay marriage, suggesting as it does so that reproductive labor is a prerequisite ultimate fulfillment (Figure 1). The story romantically and empathetically places the interest and benefit of two gay males (one Chinese man living in America, the other his shining "white" knight) above everything and every other subject‐position, with the exception of that held by the traditional heterosexual Taiwanese mother, who yearns for blood lineage above everyone and everything else. As the audience, we view the mother (Kuei Ya‐lei) and her two sons (natural son and son‐in‐law) manipulating, coercing and ruthlessly exploiting immigrant female worker Mickey (Fang Love) as a surrogate mother for this New Normal family. In short, Mickey not only serves as the house keeper, a laborer to this privileged family, she is gently pushed into becoming the foundation upon which their home‐household might continue. Mickey's body is no longer hers in this situation; instead, it is essentialized as the site of and literal embodiment for breeding and reproduction in this ultra‐modern "true story." Her position ought to provoke immediate outrage from anyone attuned to issues of gender politics, but perhaps because the two men conform to a narrative inscribed with monogamy, decency and the promises of a happily ever‐after. They are the quintessential "couple" closely aligned to heteronormative dictates, an Asian American and a white American man, gay and married. For director Barney Cheng (1971‐), who portrays himself in this autobiographical film, the couple deserves respect, to the extent that they are entitled gleefully to make use of a third‐world woman's body as a means to their end, to obliterate the unnecessary "hassle" in the details that are heterosexual consummation and pro‐creation. Simultaneously ironic and sincere, being Gay and Married is the most desirable option toward upward mobility in the neoliberal capitalist global North, even for many gender and sexual minority subjects. Thus, the loving mother and her two sons accomplish both the demand of the Law of (symbolic) Father and garner their share of the familial fantasy.

<16> Coincidentally and contigentally, Kuei Ya‐lei had already portrayed another Chinese mother from Taipei more than twenty years earlier, in Ang Lee's The Wedding Banquet (喜宴 Xǐyàn, 1993). [2] In this film, the odd woman caught between a gay male couple is the self‐determined, headstrong artist, Wei‐Wei. She is poor but talented, possessed of a Mainland Chinese' wildness and ruthlessness, yet just charming enough that the unfaithful Taiwan gay man, intoxicated, is aroused into making love. The result of their folly, the fetus, is unwanted, and even in the end she develops no more than a vague curiosity for the newborn. But in this instance, Ang Lee not once slips into self‐righteous promotion that the female body as surplus residence for gay male fantasies. In Cheng's Baby Steps, Mickey is not unlike a raw piece of meat/land to be conquered and owned, and her ownership becomes the nexus for interlinking issues of racial, class and sex/gender subjugation.

<17> At a 2012 forum for gay marriage, activist Ning Yin‐Bin argues that marriage should be a unit based upon reason and group, necessarily containing two or more people. Apparently, the radical and aggressive implications behind this statement went unnoticed by the audience at the time. [3] Current marriage discourses—both the status quo of heterosexual marriage and the aspiring gay marriage—exclusively favor individuals deemed "suitable" to enter the marriage market for intercourse. The result is a reinforcement of the petite‐bourgeois, nuclear family fantasy of the monogamous couple defending each other from that perilous world beyond, all

the while keeping their petty happiness close and the national ideology of pro‐creation closer still. These saccharine daydreams are extremely dangerous: they effectively obliterate any possible relationship-transgender polyamory, non‐biological communal collectives, sex work within marriage, inter‐generational marriage, pedophilia and gerontophilia, and inter‐marriage within families—that might otherwise subvert and "queerize" existing conjugal, familial and homestead structures. [4] An even more immediate outcome is a collective fear: everyone wants to-must-get married because the political unconscious and civilian common sense alike dictate that they do so. The state machine acts in such a way as to keep the majority of its citizens under the spell, namely that "without a normative marriage, you shall die alone."

<18> If the ideological warfare inherent to residence rights movements has to return to aneveryman, down‐to‐earth and normalized set of strategies, "anti‐(normative)‐household" queers inevitably become uncanny double agents-both front‐line soldiers excluded from a normative household and gatekeepers to the "hearth" and the warmth of the marital home. Central to this discussion are a series of provocative questions. Why would queer individuals support notions of middle‐class house and land owners, aas with their support for the Wang family? Why do they subject themselves, "endure" the unbearable sentimental rhetoric of state‐sponsored pro‐creation and all that it entails? Why do they reserve their anger and, in doing so, lend credence to an organic wholeness as normative and self‐defining?

<19> If we compare marriage to private property, the Lacanian "obscene enjoyment" projected at the destruction of a particular patriarchal family ought be thought‐provoking for us queer subjects. Non‐normative genders and Leftist subjects should not applaud the (particular, abrupt) infringement of property rights any more than normative gay subjects should cheer or allow particular heterosexual notions of marriage to be forced into or out of the system. For anti‐social queers, for example, the disintegration of a particular understanding of marriage or property does not afford pleasure-not only is the situation untenable and unworthy of celebration, but it calls for more aggressive challenges and confrontations, until such time that the state machine loses its last bit of domination over any form of marriage and residence. Instead, we ought to "queer" the concept of residence, in order to resist the "happy ending" in procreation narratives. We need by rewrite or re‐invent a "backward utopia" where queers can occupy myriad positions and where even the most despondent lives can thrive. For by radically demystifying the sentimental slogans of family warmth and the like, I welcome a world in which the appearance and essence of even the most anti‐social, deviant, non‐productive queer residents-those often dismissed as hopeless, dreadful, backward, inferior, cheap, negative, licentious, perverted, aloof, impassive, or if belonging to certain marginal lives, stubborn, arrogant, and creative-can be freed from the constraints instituted by the dominant system and the normative subjectivity in the name of "diverse family formation." In such a world, subjects might never be systematically deprived of their rights, materially or symbolically in the name of "lawful procedures."

Principal Cast and Crew of Baby Steps (2015)

Director: Barney Cheng

Mr. Lin (Tzi Ma)

Tate (Michael Adam Hamilton

Dr. Gupta (Meera Simhan)

Mother (Kuei Ya‐Lei)

Mickey (Fang Love)

Acknowledgement: Unless otherwise noted, all images were acquired under a Creative Commons license.

Notes

[1] For example, consider how the Civil Partnership Rights Alliance refutes their "opponents" by claiming that the latter defiles gay marriage with sex liberation (see quotation below). After a lengthy Q&A, both parties (the Alliance and the "opponents") magically agree upon excommunicating "sex liberation" (polyamory), incest (homesexuality), and bestiality (interspecies love)-the forms of relationship that both parties abhor and neither seeks to understand. What's more appalling is that the Alliance concludes by appeasing the "opponents" while cautioning that the abject members of "sex liberation" (polygamy, incest, and bestiality) will never be included in the sanitary, normative gay marriage system that they are proposing:

Those who oppose gay marriage often claim that gay marriage leads to "sex liberation" (just as opponents to teaching homosexuality in the classroom claim that such education encourages "sex liberation"), as if gay marriage itself cannot stand as a cause on its own. Opponents often fail to define "sex liberation" and take for granted that the term explains itself about how legalizing gay marriage will damage the (heterosexual) marriage system…. Both logically and as practically seen in the examples of other countries, legalizing gay marriage in a country or an area does not encourage the said "sex liberation" of polygamy, incest, or bestiality. We would like to ask: if there is no cause and effect between gay marriage and sex liberation, what exactly is the opponents' intention in bringing up this argument? I suggest that "sex liberation" based on a fictional causality, in fact, abuses societal ignorance towards gay marriage in order to produce a collective fear about how "gay marriage" will "disintegrate social orders."What the argument really does is attack the LGBTQ communities.

[2] It comes as little surprise that certain critics, in fact, read Baby Steps as the "sequel" to The Wedding Banquet.

[3] Given Ning's disillusionment with the romantic fantasy of gay marriage and any compliance with prevailing systems, I suggest that there are still

many subjects who are oppressed and discriminated against by the injustice of marriage systems. And what is the significance of same‐sex marriage?

Ning seems to suggest that everyone should have the right to be bound to each other, to enter marriage or form families freely. He does not insist that

marriage require people to love each other-the real meaning of marriage lies in implications behind the legally recognized bond to each other.

[4] Sex work within marriage could imply the critique of marriage as prostitution. It could also radically pervert and thereby queer the marriage union/unit as a site that endorse or even encourage a partner to perform sexually diverse practices and/or enact as a professional sex worker.

Return to Top»