Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 2

Return to Contents»

Dolls, Dreams, and Drives: Sexual Subjectivity in the Films of Kim Kyung-Mook / Earl Jackson, Jr.

Abstract

This essay will examine Kim Kyung-Mook's films to draw out the inscription of sexual subjectivity and the self-constitution of the subject as object of the Other's desire. Although the primary focus is on male-male sexuality remote from any explicit activism, the struggles for recognition within a given pairing, as well as within a subject's self-understanding, illustrate viscerally that sexuality itself is inherently political-here in its adjudication of submission, dominance, accommodation and resistance.

Keywords: outsider artist, sexuality, subjectivity, representation, technology

Outsider Prelude

<1> Kim Kyung-Mook (b. 1985) is an outsider artist, and as such I believe I need begin this essay with its own "outside," a behind-the-scenes addendum-preface to the formal text, by describing the history of my contact with Kim and his work, as well as the nature of both "unofficial" revelation and authoritarian interference. While living in Korea, I first heard around 2005 of a young gay self-taught filmmaker whose work was both inventive and outrageous. The film he had submitted in his application to the Korea Academy of Film Arts, Faceless Things (얼굴 없는 것들Eol-gul Eop-nun Geot-dul, 2005), impressed the admissions committee who also found its second half so shocking that some members refused to describe it.

<2> The next time I encountered Kim Kyung-Mook's name was in print-when in 2006 I was hired to translate/copy edit the descriptions of Korean films for the catalogue produced by the International Promotion Department of the Korean Film Council. From the entry for Kim Kyung-Mook's Faceless Things, I learned that he was born in Busan in 1985 but had dropped out of school at sixteen and had run away to Seoul. There he made his directorial debut with the short, Me and Doll Playing (나와인형놀이 Na wa inhyeong noli) in 2004. But it was the director's own description of his work that intrigued me most: "When I was a teen, sick and tired of this disgusting world, I began to meet strange men secretly. All these relationships are written in my journal, recorded by the camcorder, or between the traces of my memories." This statement underscores his keen understanding of the relations among subjectivity, representation, and technology. The pathos, moreover, was real, yet energizing rather than paralyzing.

<3> I finally met him in the fall of 2007, when I was part of the Trans-Asian Screen Institute Conference organized by Professor Kim Soyoung. She had arranged a joint screening and conversation between Kim Kyung-Mook and the filmmaker, film scholar and activist from the Philippines, Nick Deocampo (b. 1959). Kim showed his short, Me and Doll Playing; Deocampo showed his documentary, Sex Warriors and the Samurai (1996). The films were screened back-to-back, and then each director introduced himself. Thereafter, they engaged in a public conversation.

<4> Me and Doll Playing is an inventive portrayal of a young man's coming awareness of his sexuality in a repressive and heterosexist social order in contemporary South Korea (to which I will return below). Sex Warriors and the Samurai follows the life and career of Jo-An, a transgender sex worker in Manila who regularly travels to Tokyo to cater to the sexual appetites of wealthy Japanese businessmen. To prepare for these trips Jo-An takes dance classes, learns Japanese, perfects her dress and make-up, and compares notes with other sex workers on the tastes of the clientele. She does all this to support her family of eighteen people.

<5> While the films shared only sexual marginality, this common ground was a means of talking through how much sex and sexual identities and antagonisms are vehicles for multi-tasking the contradictions of race, class, national identity and global capitalism. The juxtaposition of the two films and the ensuing dialogue between the two filmmakers proved a stimulating and illuminating encounter in inter-Asian cultural studies.

<6> Comments from the audience also brought to light the repressive tradition in Korean sensibilities. Several graduate students from the English Department of Korea University, an elite private university, had attended the conference and had on my recommendation stayed for this showing. Shocked, they came up to me and suggested that this "kind of thing" did not belong in public, and they wanted reassurance that I had nothing to do with it. Their disappointment that I had indeed had something to do with it was telling. It also obliquely demonstrated the kinds of pressures Kim had faced as a defenseless teenager and the challenges he now encounters as an outsider filmmaker.

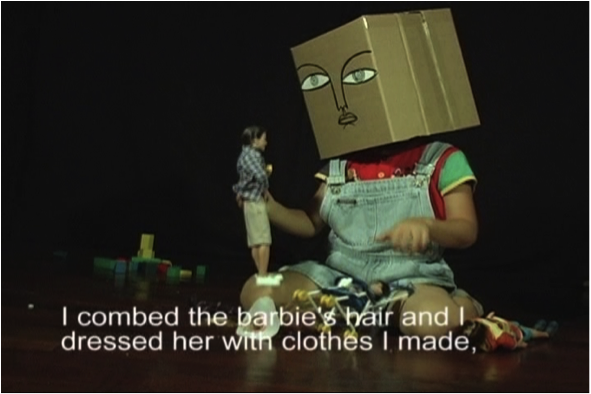

<7> Shortly after this event I emailed Kim, introduced myself and expressed an interest in his films. He sent me DVDs, and we began an infrequent but very illuminating email conversation. In one email he attached a Korean transcript of an interview he had done with someone identified on the bottom of the last page as Bastian Meiresonne. He wrote that he considered this a good text as a way into understanding him. Nonetheless he provided no context for the interview nor where it might have been published (or for that matter, in what language the original questions had actually been asked). I took him seriously then, as now, and consider the interview a valuable resource. How I might use it in the context of an academic essay with its attendant protocols of attribution, however remains an open question. [1]

<8> Then, in 2011 Kim invited me to the press screening of his latest film (at that time) -Stateless Things (줄탁동시Jooltak dongshi, 2011). When Professor Kim Soyoung and I arrived at the theater, however, there were two PR people there apologizing for its sudden cancelation, but because we were registered guests, we were each given a screener of the film on DVD. Only later did I realize why the preview had not happened: the film had been given a rating of "Restricted," meaning that it could only be shown in specialty theaters licensed to show restricted films. Unfortunately, no such theaters existed. Since that time, some of the more sexually explicit moments in the film have been cut, and the new version has been shown publically. Ironically, the restriction on the first press screening had provided me with the original version, that version that the director had intended to be seen and that would not see the public light of day. So, I have in my possession two texts, namely an interview completely without annotation and a banned director's cut.

<9> It would be only natural to ask why I had not simply asked Kim for the details of that interview, but that brings me to the most recent instance of interference from the Social Order. On January 19, 2015, he was convicted for his conscientious refusal of Military Service, sentenced to two years in prison and remanded to a prison in Seoul. On March 26 of the same year, he was transferred to the Tongyong Detention Center, in Tongyong City. Since entering prison he has only been allowed to receive email from Korean citizens, underscoring that not only is his free communication with the world at large severely restricted, but that those who are permitted to correspond with him are subject to surveillance and intimidation. It is against this background that the essay below emerges.

Rules of Engagement

<10> Critical engagement with Kim's films has been limited by their relative newness, their language (both literally and cinematically) and by their uncompromising modes of address. But it is precisely the ways these films eschew user-friendliness that gives them their urgency, demanding and rewarding a committed attention. Any description of these films must be immediately qualified. They emanate from an unapologetically "gay" perspective, yet their significance extends beyond an identity politics. One of the recurrent motifs involves the attempt of a young gay man to find sexual and emotional fulfillment from an older married man who remains only partially available. Neither a lament nor a victimology, instead these situations contribute to a more extensive understanding of a sexual scenario as a structural disequilibrium. Furthermore, desire is not an urge to be quelled either by physiological satisfaction or by the closure of a psychological narrative; instead desire remains an open question-destabilizing in its constitutive effects and affects.

<11> This essay examines Kim's films to draw out the inscription of sexual subjectivity and the self-constitution of the Subject as object of the Other's desire. Although the primary focus is on male-male sexuality remote from any explicit activism, the struggles for recognition within a given pairing, as well as within a Subject's self-understanding, illustrate viscerally that sexuality itself is inherently political-here in its adjudication of submission, dominance, accommodation and resistance.

Man and Doll Playing

<12> Kim's first film, a 2005 short entitled Me and Doll Playing appears at first almost clichéd in its confessional mode of a young man's coming out and his initiation into sex by a closeted married man and father.

<13> The film divides the Subject's life into three periods: childhood, adolescence and young adulthood, but all three periods are inscribed with a lingering child-like idiom. The first period, childhood, depicts a boy who plays with dolls, then moves on to his mother's make-up and dresses. The first-person narrator observes that "in childhood play allows the child to appreciate himself." The child wears a cardboard box with a face painted on it (Figure 1), serving to reinforce the view of the world as a child's art work, but it also conceals the actual child's face, as if to protect him from association with a forbidden sexuality that unfolds across the remainder of the film. The child figure becomes the first in a series of masked, or "faceless" figures in Kim's clandestine universe.

Figure 1. The masked face of a child

<14> The childhood of secret dress-up and play is interrupted by school and male peer pressure-an interruption that is also conveyed by a remnant of the safety of childhood that has been robbed from the boy, namely his alarm clock (Figure 2). [2]

Figure 2. The child's alarm clock

<15> This is a jarring wake-up call as well as announcing the vehemently enforced gender roles in a world where "They separated soccer and jump rope, pants and skirts. They made natural the fact that the physical education teacher was male and the school nurse was female." This regime and the other boys' obsessions with nude women proved too much for the boy, who escaped into the world of men who seemed to have something to offer him. This scenario is distilled into a drama starring the Barbie and Ken dolls he had originally played with. When the voiceover asks himself "what is it to be gay?" the screen fills with a close-up of a cellphone ringing. Its LED screen, however, reads: "Unregistered Number: cannot be displayed"-as an unidentifiable agent from the outside enters his consciousness - the married man he meets. The screen then fills with a child's notebook in which the diary entry reads: "We met and then had sex the next day." These two devices mark two axes of social life and two modes of the origin of sexuality. The alarm clock first marks the division between the relative freedom of infancy and the regimentation that begins with public school, while the phone is the vehicle for individual and clandestine offenses against that social order. In terms of sexuality, the child's own alarm clock can allegorize the endogenous model of sexuality, that which wells up from within the child in the course of his/her maturation. The mysterious caller can represent the exogenous genesis of sexuality, brought about by an external agent of seduction. Both of these origins occur within a more complex understanding of Freudian sexual etiology (Freud 1905; Laplanche and Pontalis 2013: 125-ff).

<16> Now this seems quite like a standard first-person account that might be collected within a case history, but how the film depicts the boy's first sexual experience and its ensuing frustrated/frustrating relationship repositions the film onto the level of cinematic representation and political critique. The man and his family are represented by Barbie dolls (Figure 3), and the soundtrack is an old Korean popular song about daddy loving mommy-but the plastic, static tranquility is interrupted by a doll of a teenage boy sliding by on a skate board.

Figure 3. The man and his family

<17> The father doll turns its head in the boys' direction-they embrace and the ensuing sex leaves mother and infant in the background. The subsequent diary entry complains that, while the man gave the boy money and gifts in return for sex, the boy realizes he had hoped the man would take the father role with him. Again, while this seems like a pathological diagnosis of sexual awakening, when we juxtapose the doll spectacle with the complaint, the sequence reveals itself as a parody of the negative Oedipus-the sexually awakened young man takes the position at the nuclear triangle of "Mommy-Daddy-Me" and also castigates the hoax of compulsory heterosexuality, not only for putting the father in the closet but for relegating the woman to mother and to unappreciated burden.

Figure 4. Dolls and explicit sexual performance

<18> And indeed, the first part of the film detailing the doll play and cross-dressing does not so much serve to confuse gender identification with sexual orientation as it continues the critique of phallo-centrically normative Oedipal training (Figure 4)-insofar as the young boy unconsciously accepts "castration" as the prerequisite for his desiring the father (in the mistaken belief that the mother is castrated and the mark of her desiring the father).

Faceless Things

<19> The "plot" of Me and Doll Play may also serve as a sketch of a sort for the idea developed at greater length (although not necessarily more fully) in Kim's first feature length film, the notorious Faceless Things (2005]. The film is divided into two halves whose relations are rather oblique. In the first half a middle-aged married man (Kim Jong-Chul) meets Min-Su (Kim Jin-Hoo), a very young man, in a motel room for sex, something they have been doing for quite some time apparently. The man shows only moderate interest in the boy's life but a great deal of interest in having sex with him (Figure 5). He also grows defensive and finally angry when the boy presses him on what his son is like and asks that he imagine his son's being gay. Again the boy as desiring Subject accommodates himself to the schedule and appetites of someone else's father and is left both with little to show for it but an open question. One of the closing credits announces that "Part 1 of this film is based on an authentic tape recorded in secret." In keeping with this commentary, my first approach to the film will be largely synoptic, with most of my analysis reserved for a discussion that includes the subsequent film.

<20> The man arrives first, and when Min-Su arrives he is agitated because he was stopped at the reception desk for being under-age. He has had to show his ID to be allowed in. And indeed, at first the man treats him as a child-insisting that he shower. When Min-Su leaves his clothes scattered about, the man gathers them up, folds them neatly and places them on the headboard of what will be Min-Su's side of the bed. Their conversation reveals the one-sidedness of the relation, as he questions why the man never takes his phone calls, and why the man calls him so rarely. The man does little more than insist that Min-Su shower and repeatedly asks him to clean himself "thoroughly."

Figure 5. The encounter

<21> As Min-Su showers, the man watches heterosexual pornography on the television and fondles himself to arousal for sex. Because the soundtrack sounds as if a woman is being tortured, Min-Su asks from the shower that he turn down the volume. As he comes out of the shower and gets into bed, the man changes the channel to a news report of Private Kim Dong-Min, who was serving his mandatory two-year military service, while stationed in the demilitarized zone. He had been regularly abused by his commanding officer and on the night of 19 June, 2005, after returning from patrol, he had tossed a grenade into the barracks and fired 44-rounds of ammunition, killing eight soldiers. The reporter's narrative is drowned out with the cries of mourners at the victims' funerals. That is to say that the soundscape shifts from heterosexual sex that sounds less than consensual to wails of grief that mark a tragedy exposing a lingering injustice in Korean society. The ambient sound therefore also informs the micro-political situation of the pair both in terms of sexual power and the indoctrination of young men into nationalist brutality. While the man condemns Private Kim, Min-Su says he can sympathize with him and has, in fact, begun writing a novel inspired by him. (Not surprisingly, every protagonist in Kim's films engage in writing.).

<22> The man listens to Min-Su's synopsis but asks for anal sex. Min-Su declines, but the man insists and, after wrestling with him a bit, he retrieves a black ski mask and places a mirror across from the armchair (Figure 6). Returning to the bed, he puts on a condom and penetrates him amidst the boy's muffled but increasingly louder protests (echoing the woman's protestations from the porn film). He then throws Min-Su out of the bed, drags him across the floor, and bends him over the armchair. He rapes him while looking into the mirror (now off-screen) and hurling abuses, before he drags Min-Su back onto the bed and continues his assault until he achieves orgasm.

Figure 6. The rape

<24> In the ensuing conversation, the man clearly sees Min-Su as a sideline, an aberration to be taken advantage of, as well as a secret that must be kept from his family. At one point, Min-Su asks, "Why do you meet me like this so much if your family means so much to you?" This is but one of a series of questions the man either refuses to answer or expresses annoyance over. After he departs, Min-Su returns to the bed and eventually masturbates to orgasm. He dresses, then takes a video camera out of his bag, goes to the open window in the foreground, extreme left edge of the screen and looks outward. The bark of a dog dominates the soundtrack. This positioning proves significant in establishing the relationship between the first and second halves of the film.

<25> The second half of the film is infamous and arguably unwatchable for many viewers. It features the director himself and a person identified in the credits as "?". The unidentified person is naked except for a white hood (perhaps made from a pillow case), concealing his face. It opens with the naked person lying face up on the floor with director Kim Kyung-Mook's squatting over the man's hooded face, while attempting, but failing, to defecate on him. There are many false starts and hesitations but eventually Kim succeeds in defecating on the man's chest. The man smears the feces all over himself and grips his erect penis with more, using it as lubrication. He masturbates to ejaculation, captured in close-up. The camera lingers on the mingled bodily excrements, strewn across the man's form, before going black.

<26> The screen brightens with a return to the motel room seen in Part 1. But where Min-Su had stood and held the video camera, Kim Kyung-Mook now stands. The soundtrack also returns to the barking dog heard in the original scene; unlike Min-Su (Figure 7), Kim turns his attention from the camera he holds and faces the camera recording the scene (Figure 8). The work concludes with a fade-out on his face captured in confrontation staring directly at the viewer.

|

|

Figures 7 and 8. The stares

<27> The conflict between the man and Min-Su serves as a reenactment from Kim's life, as well as a template. While the encounter appears completely one-sided, that Min-Su remains in the motel room and masturbates, reaching orgasm, suggests that the entire scenario on some level brings him satisfaction-and that he has not simply settled for what he can get. Imbalance seems inevitable and structural. And in some ways, Min-Su is far freer than the man. The man cannot accept his own sexuality. Neither can he integrate his desires with his life. Min-Su, on the outside, remains integrated within that outside and within his role as intruder within the man's isolated and secret life. The two halves of the film, then, are mirror images. The first half is a dramatization of an actual event in Kim's life, but notably, Kim does not appear in it and the sex is simulated. The second half records an actual sexual act in which Kim does appear. In the first half, the Man asks Min-Su to "wash out his asshole" to assure cleanliness for him when he penetrates him (something he does in spite of Min-Su's protestations). In the second half, Kim appears reluctant, even embarrassed, to defecate atop the hooded figure, underscoring that "scat kink" is not part of Kim's sexuality and that he does not find it pleasurable. In both halves, a "Kim Kyung-Mook" figure accommodates the desires of another, and he does so with the same part of the body. It accommodates a desire that he does not himself share. This pattern will be further explored in his next film, Cheonggyecheon Dog (2008).

Cheonggyecheon Dog

<28> The attempt at fashioning a self-image with which to meet what one believes to be the Other's desire is interiorized in Kim's far more abstract film, Chungyecheon Dog. It begins with a scene of a waterfall viewed by a mermaid (Figure 9). The motion freezes and becomes a framed picture on the wall of the apartment of another Min-Su (Park Ji-Hwan), a man who subjects himself to a ritual of shaving his legs, carefully applying his make-up and donning female clothes as he becomes the fantasy object of a caller in a phone sex encounter.

Figure 9. The mermaid and the waterfall

<29> Min-su masturbates as if he were the woman he pretends to be for the caller. The call, however, is interrupted by noise, as if a police radio had invaded the line. A strange man's voice is heard growling, dog-like, as he says, "You will never become me."

Figure 10. An erotic call

Min-su ends the call (Figure 10), and his door opens. As he himself enters the room he is already in, the voiceover informs us that this is little more than a dream he had had.

<30> He dreamt that he had gone blind as he was walking by the Cheonggyecheon River (Figure 11). A German shepherd chained there tells him that if he frees him the dog will give him eyes to see; and were he to follow him he would lead the man to his true love.

Figure 11. A Blind man

<31> Let us pause momentarily to consider the components comprising the dream. The man tells us that this is a dream of having gone blind, but we see the dream as if he had actually experienced it. But who, then, is seeing the man as he walks around, blind, if this in fact be his own dream? Rather, it should be completely dark. This suggests a double consciousness at work even at the level of perception.

<32> And on the level of cinematic representation, another contradiction is mobilized. The conversation between the man and the dog is rendered as a silent film. The image looks aged, and the dialogue is rendered in subtitles. But it is precisely because the blind man cannot see them that the way the dream is conveyed remains the antithesis to its actual experiential content.

<33>The site of the dream is also significant. Cheonggyecheon, originally called Gyecheon, is a small river running through a section of what is now Seoul. It has been in use at least since the fifteenth century. Japanese colonial authorities had changed its name to Cheonggyecheon in 1914, as part of their policy to rename all the rivers and streams of Korea. The stream divided the neighborhood into Jungno and Chungmuro; the Japanese gave the latter the Japanese name "Honmachi," or Foundation Town, and had reserved it exclusively for Japanese residents. Jungno was left to the Koreans. In this way, Cheonggyecheon became an officially enforced border between the ghetto for those colonized and the colonizers' residential area.

<34> Subsequent Japanese construction projects (both completed and abandoned) radically altered the character of the river. Such projects had diverted sewage systems directly into the river. The sewage, in combination with the thousands of displaced poor who had taken refuge in shanty houses crammed along these shores, transformed the Cheonggyecheon into a foul and profane, hazardous scar across the face of the city (Abe 2001:82-91; Pfenning 2008: 66-73). By 1958 it had become so polluted and posed such a health hazard that it was covered with concrete. In 1968 the dictator Park Chung-Hee ordered the construction of an overpass, essentially erasing any trace of the river.

<35> But in 2003, Mayor Yi Myung-Bak began an enormous and extremely expensive project to restore the river. This required tearing down Park's overpass, unearthing the buried river and pumping it with thousands of gallons of water daily from the Han River. The enormous costs of the project, as well as lingering suspicions regarding Yi’s motives, rendered this restoration quite controversial for a very long time. The result, however, was beautiful. Nevertheless, Yi had used this project to help him get elected president in 2010, in an act that would usher in years of corruption, crony capitalism and erosion of human rights. When read in this manner, the Cheonggyecheon is an overdetermined location. More to the point, the site as it exists in Min-su's dream suggests that the project was still in its early stages. The image, too, serves to excavate a secret river still not at all visible, all the while creating a blasted landscape, an industrial wasteland within which the blind Min-Su encounters the dog.

<36> Once he unchains the dog, however, it runs away and the man chases it through the streets of a crowded, albeit trendy neighborhood. On the way he encounters a group of boys that includes himself as a younger man (Lee Joo-Seung). He enters a fashion boutique and is persuaded by the clerks to try on a black dress. He enters the dressing room and re-emerges as a CIS-gender woman (Park Seong-Jun). And as a woman, she finds a man who is loving to her. The sound of a toy machine gun would change the scene. The man she was with vanishes, leaving a policeman who stands before her and demands her ID. She protests weakly, and he growls, barks like the dog in the phone call. She relinquishes her ID card, only to have him chase her through a mall as the screen splits in two: the woman and her image flee in parallel spaces that regularly intersect, causing her to merge with her own image.

<37> Eventually she is caught by the policeman and is blindfolded and left hanging from the ceiling in a kind of disco-dungeon where a werewolf, a dog man, assaults her.

<38> The film ends with Min-su back in the apartment. But we now have his psyche anatomized - in a political contest-as an internalized policeman torments him to identify himself/herself. Reminiscent of Lacan's interpretation of Freud's theory of hysteria, on the one hand, the hysteric does not know in the unconscious what it means to be a woman. On the other hand, the officer's demand for identification becomes a critique in itself - one that the film puts on display in order to refuse to answer it. Thus, the suspension at the end is not an impasse but an aporia, a refusal to submit to the imposition of law. No longer identity politics, it is instead the politics of identification.

Stateless Things (줄탁동시 Juktak Dongshi, 2011)

<39> Kim's next feature-length film examines this politics of identification at a macro-social level and does so in two parts. The first section depicts the dreadful lives of two immigrants working at a gas station in Seoul. Soon-Hee (Kim Sae-Byeok) from China and Joon (Paul Lee) from North Korea. The pair eventually rebel against their abusive employer and run away, all the while taking in the tourist attractions of Seoul. The second section returns to a now familiar scene in which Hyun (Yeom Hyun-Joon), a young man who lives alone in a penthouse apartment rented for him by Song-Hun (Lim Hyung-Guk), a married man who shows up only on occasion for conversation and sexual gratification but who can never stay the night. The emptiness of their relationship is shown in several modes, but ultimately and without explanation the North Korean refugee moves in. The final section goes silent as they paste over the windows with newspaper and tape the doors shut. Having fallen asleep, they fall into a kind of trance. They start making love, their underwear still on, and the South Korean youth appears to strangle the other. He wakes to a hazy smoke and makes his way down and onto the street. As he runs away in the final shot, we realize that it is, in fact, the North Korean who has escaped.

<40> The overt identification of the kept boy with the refugee goes further, insofar as it politicizes the economic imbalance that constitutes the lives of South Koreans. In actuality, this merging of the two boys occurs on the level of the cinematic address to the spectator, and it began earlier with a strange hinge structure. I would like to close with an excerpt that demonstrates as much.

<41> In the first part of the sequence, the South Korean Hyun lies naked, face up on the bed, and masturbates. As tensions rise and he ejaculates, he turns not toward the camera filming the movie but toward a web cam, signifying that his pleasure is not solitary or even for himself but is for the benefit of a highly specific, albeit silent viewer. But as Joon turns from the web cam to face the camera filming the scene the scene shifts to a public bathroom stall where Joon submits to giving oral sex to a masked man who films the brutal encounter.. He is there to have sex for money, something he has never done before; those images on the camera record and amplify his torment.

<42> What we have in the corpus of film by Kim Kyung-Mook is a long term meditation on sex-as-appetite and sex-as-vehicle-for-survival. Sex simultaneously becomes an all-encompassing lure toward an emotional fulfillment it negates even as it demands it. While psychoanalysis has much to say as a critical discourse and can certainly be set into dialogue with these films, they nonetheless should remain on the level of a dialogue between two explorations. In this way, Kim's films explore the intersubjective drama of sexuality on at least three essential levels: intra-psychically, interpersonally, and macro-socially. And each level is comprised of and reflects its own contradictions, a priori, in opportunism and as opportunities.

Acknowledgment: The author expresses his sincerest appreciations to Korean director Kim Kyung-Mook who holds the rights to all images used herein and who has graciously consented to their use within this essay.

Notes

[1] I will refer to it as the "Uncontextualized Bastian Meiresonne Interview, Korean translation, provided by Kim Kyung-Mook, on 15 January, 2013.

[2] In the Meiresonne Interview, Kim mentions that his father had him committed to a mental hospital when he was eighteen, one of the few details that does not appear in some form in Me and Doll Playing.

Works Cited

Abe, Yoshiaki, "Toshironteki Fuan: Kankoku Eiga vs Zeze Takehisa." Eureka (Nov 2001): 82-91.

Freud, Sigmund. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. Vol. 7: The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887-1904. Ed. and Trans.by Jeffrey M. Masson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1905.

Laplanche, Jean, and J. P. Pontalis. "Fantasy and the Origin of Sexuality." In John Fletcher, Ed. Freud and the Scene of Trauma. New York, NY: Fordham University Press, 2013.

Pfennig, Richard. "Das Thema Grossstadt im koreanischen Film." Special Issue of Seoul Bang. Nils Clauss and Udo Lee, Eds. Stadt Bauwelt 179 (Dec 2008): 66-73.

Return to Top»