Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 2

Return to Contents»

Drag Queens, Thorny Devils and Frilled Lizards: "Queerness" Takes to the Outback in The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994) [1] / Linda Rohrer Paige

Abstract

This essay explores the gay road movie Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994) as a paradoxical classic of Australian cinema. Three protagonists, drag queens with complicated and frustrated private lives launch themselves into the Outback, a harsh environment dizzyingly different from the febrile sophistication of Sydney. At first we see only extreme culture-conflict, comic or tragic; but as the film progresses, viewers and characters alike find surprising affinities between the exotic fauna and the extraordinary landscape itself. Ancient and modern images blend to reveal the beauty of a continually changing continent and its people.

Keywords: Australian hero, difference, ocker, camp, self-identity

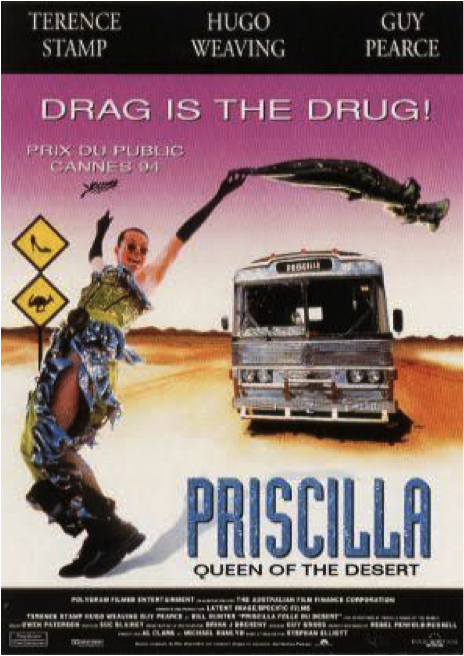

<1> For film audiences, the phrase "Australian hero" perhaps conjures up images of a Crocodile Dundee: an individualist and survivalist, manly and tough, comfortable not just in the inhospitable Outback-which boasts, as we know, some of the most venomous creatures in the world-but also capable of wrestling a crocodile and winning. The phrase suggests the clichéd Aussie hero of decades past. In his camp classic The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), writer and director Stephan Elliott makes full use of these stereotypical expectations but turns, or twirls, them into something rousingly different (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Film poster

<2> Offering a new twist on two successful genres, the "road movie" and the "buddy" film, Priscilla's creator experiments with new "ways of being" an Australian male. [2] Elliott's protagonists are three drag queens from Sydney-two homosexuals, Anthony/Tick/Mitzi (Hugo Weaving) and Adam/Felicia (Guy Pearce), along with a post-opt transsexual, Ralph/Bernadette (Terence Stamp)-who wrestle with problems of identity. Throughout the film, these heroes are set not against spectacular feats and crocodiles, but rather against the perils of everyday life in the desert. Riddled with angst and bedraggled with guilt, they need to transcend their personal pain and the stagnation that prevents them from moving forward. Each, in one way or another, must learn to "fly," to soar above individual limitations; and their encounters along the Australian Outback, with its people and its landscape, will help them accomplish just that.

<3> The drag queens share one flaw in character: they are limited by their guilt and fears. Tick/Mitzi has been leading an unexpected secret life: as Bernadette teasingly puts it, "she bats both ways." Feeling unappreciated in her pursuits as a drag queen (indeed, rowdy crowds sometimes hurl a beer can or two in her direction), she seems equally unfulfilled by her part-time job selling "Wo-man" (pronounced "Woe-man," a campy double entendre), a skin cream "for the heavy-duty woman in us all." Her career at its heyday in the 1960s, Ralph/Bernadette mourns the loss of her 25-year-old lover and husband, Trumpet, who has died suddenly. Depressed and enervated, she is left to combat the ravages of "raccoon eyes"-tears smear her mascara. Adam/Felicia yearns for excitement, having grown weary of an awkward relationship with "Mommy," who finances their trip to the Outback in hopes that her son may meet "some lovely country girl" there and outgrow "this phase." Further, Adam/Felicia dreams of climbing King's Canyon, a favored Australian tourist spot, in "full drag"-heels, tiara, and sequins-and, in doing so, presenting herself to the world "as a queen."

<4> Drastically in need of change, the queens accept a booking for a four-week cabaret gig in Alice Springs. This entails traveling from their home in New South Wales, across the desert and up into the Northern Territory, then curving back down to Alice, a distance half way across the continent. They embark upon their lengthy journey aboard a used tour bus they christen "Priscilla, Queen of the Desert." Their trip begins favorably enough as they depart from the Imperial Hotel in Sydney, with a gaggle of friends from the LGBTQ community showering them in good wishes and party streamers, launching them on their journey.

<5> As the camera pans across the bustling harbor and skyline of Sydney from above, Priscilla appears oddly diminutive--like some queer bug caught on a toy track. Nor is this the only oddity concerning Priscilla: she seems ill-equipped for the perils of the Outback, filled with nothing but an extensive wardrobe, a "first aid" cabinet filled with liquor, a camera, a sewing machine, and an unusually large plastic spray gun, hardly provisions for such a formidable journey inland. Yet Priscilla and her inhabitants share a hidden, deep affinity with the desert and its natives. This affinity between them prompts them to rethink their understandings of "belonging," the "natural" and "transcendence"-all three recurrent themes in Priscilla. The filmmaker sees commonality through the lens of difference.

Priscilla and the "Aussie Male"

<6> Out of the relative safety of sophisticated, cosmopolitan Sydney, Bernadette, Tick/Mitzi, and Adam/Felicia quickly find themselves in a very different world. In the small towns through which they pass, Broken Hill and Coober Pedy, for instance, they encounter characters stereotypical of the strong and rugged peoples who inhabit the Outback. Peter C. Kunze characterizes these characters as "ockers" (2013), a type commonly considered to be heroic (as in the 1982 film Gallipoli, or the long-running Mad Max series), or even as coarsely comic as in the 1972 Adventures of Barry McKenzie. [3]

<7> During four hours of travelling, the inexperienced trekkers appear to ignore the scale of the challenge that lies before them; once they stop, however, they stand awe-stricken, gazing at the lonely ribbon of highway that seemingly crawls away and up into the distant blue and purple heavens. Only now perhaps do they comprehend their own minuteness. The camera catches the moment, as we see them sandwiched between the layered terrain and the endless skies. In line with the quirky or camp humor of the film, Adam resorts to understatement: "Perhaps we should have flown."

<8> In surreal fashion, the queens strut through the small mining communities of the Outback as though oblivious to any danger lurking within. In the tiny community of Broken Hill, for example, they think nothing of the town's possible reaction when announcing their intention to do some "shopping." As they step to the sidewalk, the three appear superhumanly tall and gangly, their heads towering above the homespun settlers whom they pass. They are greeted with mouths agape, stares, and immediate double takes at their exaggerated cotton-candy and sippy-straw hair-dos, as well as their stilt-like heels. To young and old alike, these outlandishly-dressed strangers "invading" their streets look other-worldly. Even a German Shepherd cocks its head as if befuddled by the sight.

<9> But distrust and antipathy go two ways. Quickly bored with the "tackarama"-style of the Palace Hotel where they must spend the night, the queens announce their intent to go out for drinks-which, of course, will necessitate another "performance" before the locals. [4] Time and again, Elliott casts his heroes into the human fray-thereby keeping audiences tense, anxious, constantly aware of the risks involved. As they enter the Hotel bar, all conversations halt. From the recesses, a solid figure pushes her way between two rough-looking Aussies, and as she comes into focus, we hear her unpleasant voice: "Well, …Look what the cat dragged in. What have we got here, eh? A couple of show girls?" "Old Shirl" (June Marie Bennett) is the only character in town willing verbally to acknowledge difference. Further, by referring to them as an indefinite "something" that a cat could drag in, she positions herself as their nemesis, one who "de-personalizes" them. She suggests that their "queerness" makes them less than human. Sneering at the unwelcome visitors, she draws out her final words: 'Where did you 'ladies' come in from, Uranus?" This stumpy, dirty-faced woman, clad in a "wife-beater" t-shirt, levels further puerile insults as she continues, "We ain't got nothin' here for people like you."

<10> But Shirl is herself a gender-bender-awkwardly feminine and overtly masculine. Having broken barriers by gaining access to the male sphere, the bar, she enjoys, as her nickname implies, a degree of familiarity with-even cordiality from-the otherwise conventional Aussie males. Her accepted presence among men like this underscores the fluidity of gender and self-identity. Critics argue variously about her sexuality-although most assume her to be butch, a "bull-dyke." Ann-Marie Cook, for instance, calls her "the lesbian-coded Shirl" (2010: 3-26), and John Champagne goes further, labeling her "the mean dyke, Shirl" (1997: 66-88). Her presence adds to the layers of comedy as she confronts Bernadette. Bernadette is urban and feminine; Shirl is rural and butch; but Bernadette can still both insult and drink better than Shirl-in a world of "ocker" behavior, Bernadette, with the physical strength of a man, can still "beat" the biological woman. Onlookers delight in seeing Shirl bested, as Bernadette is rewarded by gusts of jeering laughter and a sense of hard-earned success that even her suspicious hosts can understand.

<11> The next morning, the queens stumble upon a wanton act of vandalism when departing the hotel. Scrawled in bright red letters across Priscilla's side is an overt message of hate: "AIDS FUCKERS GO HOME!" Any sense of camaraderie they had perceived the night before now gone, the three travelers in light of day know that they do not "belong." Mitzi confesses to Bernadette that although she thinks that she is used to these barbs, nevertheless, they still tear at her. The homophobic message indicates a deeply ingrained attitude of Australians toward the "Other." In Priscilla "a white, working-class culture of 'mateship,'" as Tincknell and Chambers surmise, "is offered as both profoundly homophobic and as intrinsic to Outback masculinity" (2002: 149). Later, as they break away from the "sealed" highway and venture onto dirt roads, in the hope of shortening their trip, the engine unexpectedly quits; this foreshadows a series of comic images of emasculation, all meant to underscore the queens' lack of ocker prowess when confronted by the desert elements. There is a strong sexual undertone when Mitzi lifts the hood of the engine and inadvertently drops ash from her cigarette (obvious phallic imagery) into it, subsequently declaring that she knows "nothing" about "that bonnety thing." Tired of their quarreling, an exasperated, agitated Bernadette packs up her gear (purse, scarf, and sunhat), and ventures forth into the blazing Bush sun, declaring that she is off to get the "cavalry."

<12> Thoroughly dehydrated and confused, Bernadette finally spies a vehicle emerging from the heat. The couple inside glimpses her too, figuring (ironically) that she is, in fact, a "lady" in distress. Puzzled by the peculiar sight of a lone female walking in Bush territory, the Spencers, nonetheless, invite her to climb in the back of the vehicle, where she finds squeezed against her feet a dead kangaroo, obvious "road-kill" and perhaps the couple's evening meal. One man's tastes, however, are not necessarily those of another. Once delivered back to the bus, Bernadette summons Felicia and Mitzi to meet their "saviors," and the hilariously campy scene goes sour as the elderly couple is confronted with a bifurcated image of Mitzi in semi-drag-man on top, woman on bottom. The "cavalry" reacts viscerally, panicking and racing away-as if queerness were somehow contagious.

<13> But just when rejections appear the norm, Mitzi succeeds in bringing back the cavalry: a true savior, in the person of Bob (Bill Hunter)-the archetypal ocker, an uncultivated Australian working man who enjoys his beer and "barbies." As a skilled mechanic, adept at "making things run," he is, at first sight, everything the drag queens are not. Straight and married, he remains a man of few words, in stark contrast to the outrageously dramatic and loquacious queens. Unlike the Spencers, however, he readily offers his assistance.

<14> Inviting the colorful visitors to his home, one of the few edifices erected in the small, isolated desert settlement, Bob introduces them to his Filipina wife, Cynthia (Julia Cortez), who prepares them a meal. Now he divulges that, in his younger days, he once attended the cabaret of "Les Girls"- to which Felicia replies with a pun that he is now in the presence of the most famous "Lay Girl" of all, Bernadette. Unthreatened, he invites them to perform for his mates at the local pub. They, however, prove less receptive than Bob has anticipated.

<15> As they enter the stage to a raucous disco tune, wearing tutus and grotesque wigs, the queens shock the Outback males, who react with stunned silence. Bob, we realize, has misjudged the situation and is further thwarted by his own domestic difficulties. Cynthia has a performance of her own in store for the crowd. A high-pitched warbling trill piques everyone's attention: she appears, wearing a sleek zippered zebra costume with matching garter and hose. Tipping her Fedora hat, she begins her own dance routine before the ogling, gawping customers. Excited to watch a genuine biological woman, rather than the guise of artifice, the desert men encourage her to "perform." She kisses ping pong balls, drops them down her unzipped front, and discharges them, one by one, from her vagina and into the hands of the men around her. Only now does the camera move in for a close-up of the startled, disheveled queens: their "backs against the wall," they are reduced to antiquated porcelain dolls, worn and flawed, their original beauty diminished by use.

<16> The film reaches its climax in the queens' next stop, Coober Peedy, a mining town constructed, for all practical purposes, underground. [5] Here, according to Bob, the men do nothing but "climb down holes" in the ground, "blow things up, and then climb back" to the surface to repeat the process again. These hardened miners are a strange breed, used to flirting with danger, living as they do underground, on the edge of catastrophe. [6]

<17> Felicia, too, flirts with disaster. She crashes the "boys' night out boozer," where Bob and a group of tough-looking miners have gathered for barbeque and beer. Mincing her way up to a well-built male, she bats her eyelashes and orders something that she knows to be unavailable, "a Bloody Mary." The miner, Frank (Ken Radley), almost immediately volunteers to give her a "tour" of the town. Like all his local mates, he accepts without question that he sees before him a beautiful woman-until he suddenly notices her masculine arms and turns on her in fury. Not content with verbal abuse, Frank intends violence, a rape. Directing his friends to spread "his" legs apart and hold him down, the miner begins unbuckling his belt when Bob heroically intervenes. Frank threatens him directly-"Put the faggot down and get outta of here, or you'll be next"-but Bob displays courage by staying and answering with his own demand: "Leave the little bugger alone." Frank's reaction is chilling. He now finds Bob suspect and threatens that he will be next if he does not desist. In supporting Felicia, Bob challenges and destabilizes the hegemony of the miners and their unwritten, but expected, privilege over those they would marginalize. Frank feels betrayed by his "mate" and considers Bob tainted. Anyone, he assumes, who supports or defends "queerness" must be "queer." Michael Schuyler, in his examination of queer cultural critiques, surmises that "queerness destabilizes heteronormativity, upends definitional determinacy and power…" (2011: 38). Frank's system of belief, including his ideas about power and sexuality, is threatened and compromised.

<18> Felicia is finally saved, however, not by Bob but by Bernadette. Not to be outdone, she "knees" the would-be rapist and informs him that she should "consider himself fucked." Thus, the "woman" takes charge and "fucks" the rapist, bringing him to his knees with "her" unexpected prowess. Her action further delimits staid notions of gender and sexuality by embracing the feminine and the masculine in a singular expression.

<19> By this point, the audience clearly understands that Bob is more complex than he first appeared. Looking back to his initial meeting with the queens, we see that his whole life is surprising for an Aussie stereotype. His enthusiasm for "Les Girls" is a crucial example. His marriage to Cynthia also shows him as far more passive, less sure of himself, than his handling of Priscilla might suggest. He reveals that he is married to Cynthia because she has said so: we see her in flashback triumphantly waving a certificate in his face. Never does Bob try to weasel out of this union, despite his wife's embarrassing, emasculating behavior-she blows balls (figuratively speaking, testicles) out of her vagina and complains of her husband's "little ding-a-ling." Only after Cynthia herself flounces off is he free of her; and once free, he immediately agrees to accompany the queens on their long journey to Alice Springs. Felicia makes clear that he should expect no patriarchal privilege on board Priscilla. "Just because you may wear the pants doesn't mean that you're the boss," she warns; and Bob gladly agrees, ironically so, to sleeping on top of the bus rather than expecting others to give up their places for him. Apparently he is contented; he enjoys the queens' company -one of them, in particular.

Natives and Aliens: An Aboriginal Welcome

<20> Prior to Bob's joining the queens on their trip, the one exception to their dismal record with the inhabitants of the Outback lies in a short sequence in which they meet a group of the indigenous peoples of Australia. While practicing their routine in the desert night, the trio are startled by a strange apparition who strikes fear into them. "Nice night for it," a friendly voice, however, quells their fright. Alan (Alan Dargin), an Aborigine, has stumbled upon their camp. To him, the queens are not abhorrent at all: instead of running from them or judging them, he offers them a genuine welcome. So wholly accepting is he of their difference, in fact, that he invites them to return with him to his tribe's encampment, not far from where Priscilla has broken down.

<21> The queens take seats on stones that Aboriginal children relinquish for them. Together, the group listens to the folksy music of "Feeling All Right," performed by three tribe members with guitars, as embers and ash fly from the fire. At first, Mitzi seems apprehensive, remarking that she believes that they "crashed a party." We might conjecture that these people, who live so simply, would react with bewilderment, even hostility, to the conscious artifice of the flamboyant newcomers. Not true. Unlike people in urban areas, they, tied so very closely to ancient tradition and the land, display an instinctive acceptance of transgender performance as a fact of life. They seem to believe in sharing, embracing a system of reciprocity that the guests recognize includes them: at last Mitzi announces, "Well girls, I guess it's our turn." Then the trio, wearing jumpsuits with large flower bouquets for headdresses, performs to the Gloria Gaynor rendition of "I Will Survive." Adding to the music, the ancient didgeridoo accompanies the queens as they lip-synch; and a new sound is born, a blending of old and new. The audience proves receptive: everyone joins in, clapping and dancing in synch. Not intimidated by the queens or feeling his manhood weakened in any way, Alan dons a silver jumpsuit, similar to those that the queens wear, and eagerly participates in the performance, improvising and thus broadening the sphere of experience for all.

<22> Some critics, Pamela Robertson among them, object that the aboriginals are viewed condescendingly, or marginalized (1995). But Elliott takes trouble to show the acceptance they offer, the pleasure they and the queens quickly take in each other's company, and the apparent harmony between the two different, but equally extrovert, performance styles. This little episode provides the queens with their greatest performing success of the whole film. From the aboriginal point of view, these are just another kind of interloper-a less threatening one, perhaps, than the colonizing "white man."

Queens and Country: Priscilla in the Landscape

<23> Thus far, we have considered only the human interactions experienced by the queens on their journey. All the while, however, another strange encounter is in progress: that between Priscilla and the landscape through which she passes. Hauling a gigantic slipper on her roof, the bus looks out of place, her silhouette emblazoned across the vast terrain of sand, shrubs, and ancient peaks. She invades the pristine desert with her gaudiness, exacerbated by arias from La Traviata performed from the slipper by Felicia, who appears outrageously dressed in her long, silver gown streaming in the wind. She lip-synchs, while Priscilla, as if in accompaniment, bellows forth orange smoke from a fog machine that paints the horizon orange and yellow. The camera unfurls the majestic expanse of land and skies, in strong contrast with the shiny and trendy "queerness" of Priscilla.

<24> Each of the queens has a particular moment set against this landscape. Bernadette, going for the "cavalry," departs with a studied elegance in her linen slacks and big scarf, across miles of sand. The camera captures her in various poses: stepping unsteadily through stubble and shrubs, sitting on a large stone, refreshing her melting lipstick, peering from over high, rocky cliffs at seemingly endless vistas before turning back and resuming her wanderings. The queens make no concession at all to this challenging terrain: we see them performing their way across it, whether anyone is watching. Priscilla herself decked out in drag sums up how out of place her occupants are in this rugged land. As they enter Cooper Peedy, they pull over: they see creatures carved out of wood, prehistoric-looking reminders of Australia as a wild and ancient land. For the most part, however, they seem wholly unaware of the distinctive fauna they pass. The camera zooms in privately on a wonderful menagerie of thorny toads, frilly lizards, and other creatures. The queens seem very different, conspicuous, vulnerable, out of place.

<25> And yet, as their journey continues, we become aware of an affinity between the travelers and the animals they ignore. Take rabbits, for example: Felicia, in probably her only mention as such, talks about "rabbits in the wheel-wells." Later, after the near-rape, Bernadette wraps a bandage round Felicia's head, tying it at the top, resulting in an unmistakably rabbit-like appearance. When they stop at a salt-water lake, the camera isolates a bird above them; the queens do not see it, of course, but later we find them making a kite out of one of Felicia's dresses and throwing it up to the sky. The face of the kite may bear a resemblance to Bernadette's; it speaks to the queens and their heretofore unrealized ability to soar above their personal pain and setbacks. Felicia, erasing the hateful graffiti acquired in Broken Hill, dangles bug-like from the roof upside down from the side of the bus. Another time, the camera pans away to reveal a gaudy little figure gesticulating against the vast, empty landscape. Mitzi is the very emblem of a queen in exile, but as the camera moves away and toward single, seemingly prehistoric insects and reptiles and their spectacular colors and shapes, viewers see an unexpected similarity, their display complementing the unusual glitter and brilliance of the queens. Just as these creatures forge a path for themselves across the desert, so too do the drag queens move forward, unrestricted, with their plans and their lives. The queens, as we come to realize, are trying to "spread their wings." Felicia's dress used as a kite achieves lift-off, and with the end of the film we see it arrive, in a rather surreal sequence, in a version of ancient China. The exotic beauty of the landscape itself, as a strange backdrop for Priscilla, perhaps far more sensibly tackled in the sturdy plaids and khakis worn by the locals, suggests a visual balance to the splendor of the queens. Their performances against the dunes look striking, even bizarre but, on a second viewing, appear in harmony with the surroundings: in these instances, the landscape becomes a backdrop against which they transform into dazzling creatures. When they do fulfil Felicia's dream of climbing up King's Canyon in drag, they look, as we see, both incongruous and strangely at home.

Three Queens in Alice

<26> Both the journey and the film reach an end in Alice Springs. By the time we get there, we know that the queens' own stories have become less simple than their relentlessly brittle, campy conversations seemed to suggest. The mechanic with a taste for drag and the drag queen with the physique of a man, Bob and Bernadette have developed a romance. He teaches his new romantic interest about engines, while she looks on, enthralled. He brings her flowers. To him, she is a woman; to her, he is a "gentleman." Whereas the film underscores that Bob's original, biologically female wife was, in fact, no fit partner for him, the exotic Bernadette proves far more suitable. Ultimately, they remain together in Alice Springs.

<27> Mitzi's story is still more complicated. The engagement awaiting them in Alice Springs has been organized, she confesses to Bernadette, by her female wife and mother of her near-teenage son, Benjy. She travels to Alice both as a performer in cross-dress and as a husband returning to domesticity. Mitzi's family is a variation on the more familiar family, but in this instance the wife runs the show, the husband performs in frilly dresses and the son adores, eager to see his father perform an Abba routine in drag.

<28> All this is not to say that the queens lose those outrageous, jagged or alien qualities they possess at the beginning, seemingly irreconcilable with their surroundings. Just the opposite, as three apparently inassimilable beings develop and accept rich and complex relations with the people they encounter along their way. The Australian Outback, however antagonistic, becomes a catalyst for change.

<29> After multiple, seemingly endless dress rehearsals-in Bob's original town, alongside the aboriginals or alone in the landscape-the trio take their performance to the stage. It is not a great success: the applause comes from friends and family only. But there, wonderfully, they offer the film audience a reprise of all the fabulous animals they have failed to notice on their journey.

<30> First, they are lizards, the notorious "thorny devils" modeled on the thorny lizards peculiar to Australia-previously spotted by the camera earlier along Priscilla's journey. The performers appear scary and reptilian, their thick, long, dinosaur-like wagging tails trailing along the stage; they wear sparkling orange, sequined jumpsuits, along with glittering lizard-like headdresses, their tongues a-flicker. Thereafter, they transform into awkward and enormous feathered birds, their headdresses giant emu heads. From this, they become butterflies or moths, in blue skeletal costumes with parachute netting. Finally, they are women, with glorious hair piled high and with parasols that, at the end of their act, turn into fans, then wings, mirroring the huge fanlike roofs of the world-famous Sydney Opera House. We see a metamorphosis before our eyes, not just from one living organism to another but, by an even greater transition/transposition, from animals and insects into a building-and perhaps that one the most iconic in Australia. This whole sequence includes both the most ancient creatures of Australia and its most famous manmade construction, linked in such a manner to suggest a world of possibilities and change where no one thing ever remains the same.

Figure 2: Ascending King's Canyon

<31> There is one last engagement to fulfil. Felicia promised to climb King's Canyon in a dress in a characteristic piece of bravado, caustically summed up by Bernadette as "a cock in a frock on a rock." Before Felicia and Mitzi return to Sydney -and before Bernadette choses to remain behind with Bob-the three of them make the climb. As they stand at the top, seeing the landscape, for the first time, they resemble large exotic birds, their extravagant, colorful plumage blowing in the wind (Figure 2). In this particular instance, their flamboyance allows them to fit in. Their adventure now complete, Bernadette says what everyone now feels: "Let's go home."

Outrageous in the Outback

<32> After Priscilla's triumphant sashay into the cinema, two other entertainments appear that taken together clinch some of the points made here about the film and its particularly Australian quality. The stage adaptation of the film, produced in 2006, plays up the role of the drag-queen bus: it features "a huge bus that changes shape and colour" (Lagin 2006). The American film, To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything, Julie Newmar (dir. Beebon Kidron, 1995), follows three drag queens on the road. It reminds us of much of what we witnessed in Priscilla, in particular the striking contrasts between small-town locals and exotic queens and the emergent sense of harmony. The American film lacks, however, the special sense of place, the wide shots of landscape, and close-ups of animal life provided in the Australian film. In Priscilla, we witness just what a special gift Australia, a continent separated from the larger primordial land mass so long ago that its fauna has evolved along unique lines, is to the skilled filmmaker. We are presented with the extraordinary and the exotic in juxtaposition. These elements make the film so visually memorable and give it its particular Australianness and its special complexity.

Principal Cast and Crew

Director: Stephan Elliott

Writer: Stephan Elliott

Anthony "Tick" Belrose/Mitzi Del Bra (Hugo Weaving)

Adam Whitely/Felicia Jollygoodfellow (Guy Pearce)

Ralph Waite/Bernadette Bassenger (Terence Stamp)

Shirley (June Marie Bennett)

Young Aboriginal man (Alan Dargin)

Bob Spart (Bill Hunter)

Cynthia (Julia Cortez)

Marion (Sara Chadwick)

Benjy (Mark Holmes)

Acknowledgement: Unless otherwise noted, all images were acquired under a Creative Commons license.

Notes

[1] The author expresses her sincerest heartfelt appreciation to Professor Julia Griffin of Georgia Southern University for many insightful comments on this film. Any shortcomings are, however, entirely the responsibility of the author.

[2] Philip Butterss argues that this time, the beginning of the twenty-first century, proves an excellent time for a "road movie." What better time than a burgeoning new century for a filmmaker to employ the "road movie" as a venue of "discarding old definitions of masculinity," ones "no longer serviceable" (2000: 227-236).

[3] As Stephen Crofts describes this genre, it "celebrated male bibulous and sexual exploits, extoll[ing] the vulgar and irreverent, was predominantly working-class and anti-intellectual, and insisted on the Australian vernacular" (cf. Kunze 2013: 51). Kunze discusses at length the influence of this tradition on Priscilla.

[4] Due to the popularity of the film in 1994, the Palace Hotel has since become a popular Australian tourist haunt, and fans regularly request to stay in the "Priscilla room."

[5] The name in one aboriginal language denotes "white man's hole."

[6] The imagery here-going down into a hole to blow things up-again suggests a sexual subtext.

Works Cited

Butterss, Philip. "Australian Masculinity on the Road." Media International Australia 95 (2000): 227-236.

Champagne, John. "Dancing Queen? Feminist and Gay Male Spectatorship in Three Recent Films from Australia." Film Criticism 21.3 (1997): 66-88.

Cook, Ann-Marie. "More Than Just a Laugh: Assessing the Politics of Camp in The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of The Desert." In Representation and Contestation: Cultural Politics in a Political Century . Amsterdam, Netherlands: Rodopi, 2010. Pp. 3-26.

Kunze, Peter C. "Out in the Outback: Queering Nationalism in Australian Film Comedy. "Studies In Australasian Cinema 7.1 (2013): 49-59.

Lagan, Bernard. "Priscilla, Queen of Desert, Film, and Now the Stage." Sydney Times October 2, 2006. Padva, G. "Priscilla Fights Back: The Politicization of Camp Subculture." Journal of Communication Inquiry 24.2 (2000): 216-243.

Robertson, Pamela. "The Adventures of Priscilla in Oz." Media International Australia 78 (1995): 33-38.

Schuyler, Michael T. "When Jesus, Moses and Gay Pageant Coaches Go Camping: The Function of Camp in Documentary Films." Studies in American Humor 23 (2011): 29-47. The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert . Dir. Stephan Elliott. 1994. Film.

Tincknell, Estella, and Deborah Chambers. "Performing the Crisis: Fathering, Gender, and Representation in Two 1990s Films." Journal of Popular Film & Television 29.4 (2002): 146-155.

To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything, Julie Newmar . Dir. Beeban Kidron. 1995. Film.

Return to Top»