Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 2

Return to Contents»

A Directors' Roundtable: Introducing Anysay Keola, Leon Cheo, S. Louisa Wei and Reid Waterer

<1> JAMES A. WREN: It is my sincerest pleasure to welcome each of you here today to discuss your works and to help our readers with reconstruction to understand in more depth the current state of filmmaking and especially any depiction of LGBTQ characters or issues. We have with us Anysay Keola, Leon Cheo, Louisa Wei and Reid Waterer.

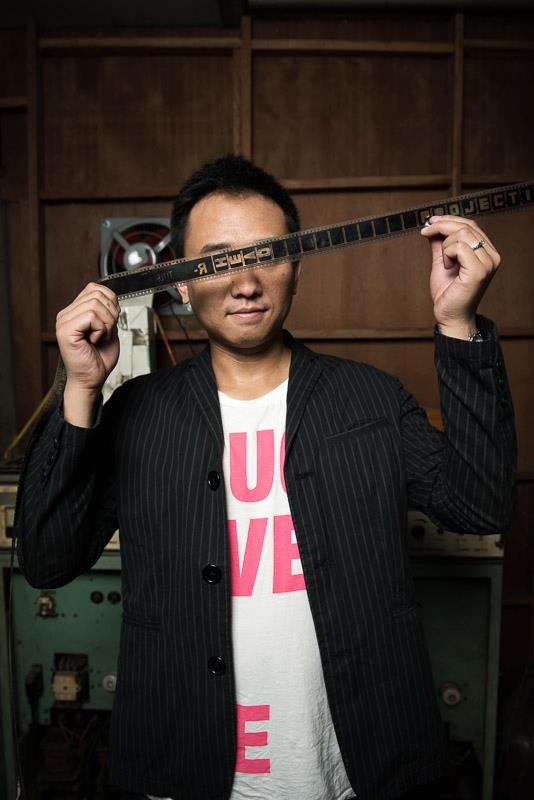

<2> I first heard about the director Anysay Keola in a roundabout way. I had heard that he was doing a film, Vientiane in Love , I believe, and one of the couples he wanted to portray was a gay couple, but the government in Laos had not approved the script. I would later learn that there was much more to his story that needed be told (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 and 2. Anysay Keola (Photo courtesy Lao New Wave Cinema Productions, Ltd. of Guillaume Megevand)

<3> I have to admit that I have only recently become acquainted with Leon Cheo (Figure 3), and

this after having seen his brilliantly intricate short film,

Swing

. I soon learned that he was from

Singapore originally and had completed his work in films studies at Chapman University. He is

also an alumni of the Berlinale Talents (2014), Asian Film Academy (2013) and Tokyo Talent Campus (2012).

Figure 4. S. Louisa Wei

<4> It was the same sort of serendipity that brought the Hong Kong director and film scholar, Louisa Wei, to my attention (Figure 4). I had the good fortune to hear of her from another film scholar living in Hong Kong, Xavier Tam, but it was another friend and scholar, Shi‐Yan Chao, who actually put me in touch with her. I quickly learned of her extensive work in film history and production and was fortunate enough to see her feature‐length film, Golden Gate Girls (2014). Her work is a wonderful introduction to-in fact, it is the first work to focus on-the amazing film pioneer, Esther Eng (1914‐70). Eng, while born in San Francisco, went on to become who became Hong Kong's first female director in 1937. It also want to take a moment to congratulate Dr. Wei on the release of her new monograph on Eng, The Legend of Ester Eng: Cross-ocean Filmmaking and Women Pioneers, published by Chung Wah Books, a much-respected publisher with nearly a century of history in the field. For those who have a chance, I highly recommend that you pick up your copy-the story is certainly fascinating, and just as impressive are the number of photos from Eng's life and works, introduced in the text.

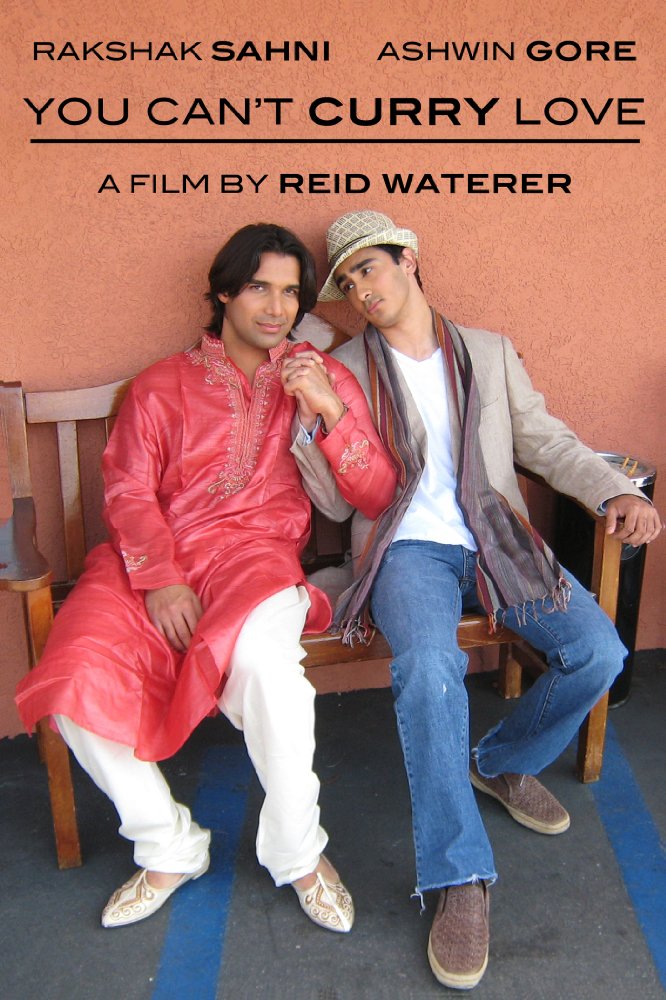

<5> I got to know Reid Waterer after I had viewed his film, YOU CAN'T CURRY LOVE (2009), at least a dozen times. Shortly thereafter, I learned that he had grown up in a house in the San Jose area and that he now resides in Los Angeles (Figure 5). A veteran of 200+ film festivals across six continents with his award‐winning films, Reid suggests that his love of film blossomed as a child when his father took him to see such classics as Ran, Diva and Das Boot at the Camera One Cinemas near San Jose State University during their US theatrical releases. A graduate of USC Film School, he began his career with a brief stint working for Peter Bogdanovich before moving into editing movie advertising trailers and TV spots. Alongside his films, he has created ads for The Hangover, Rounders, Diary of a Mad Black Woman and Mamma Mia! His 2004 feature, The Deviant, was released on DVD or television in five countries, including the United States, leading critics to refer to him as "a talent to watch."

<6> His short films have achieved acclaim in print reviews, on the festival circuit, on a successful DVD, and online. His work has screened in universities, cinematheques, and art museums around the globe. Among the many prestigious festivals that have screened his work are the Palm Springs International Short Film Festival, Hawai'i International Film Festival, Provincetown International Film Festival, London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, Los Angeles OutFest, and Frameline San Francisco. He was a nominee for the £25,000 Iris Prize and winner of over a dozen Best Short jury and audience awards thus far. As if this were not enough, he has also placed highly in several screenwriting competitions.

Figure 5. Reid Waterer<7> Now, I suspect I have said enough-and then some. Without further delay, I want to turn our attentions to our distinguished panel of directors. I welcome each of you here and thank you for having taken the time away from what I know are very busy schedules to share your insights.

So, let's get started. Perhaps, if possible, each of you might try and answer several-what I see as-core questions about each of you and your works.

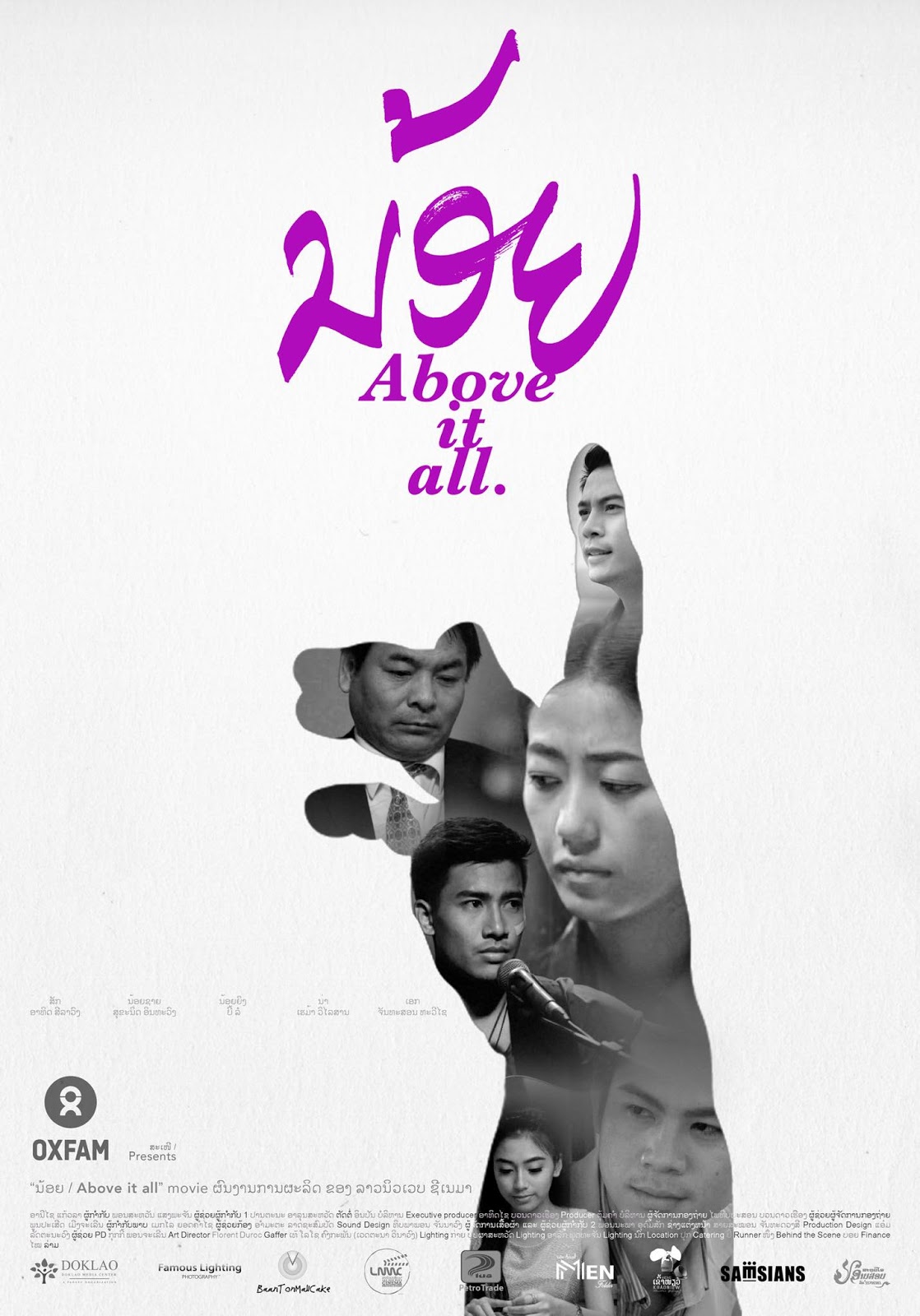

<8> ANYSAY KEOLA: Thank you, Jim. For those of you who do not yet know me, my name is Anysay Keola. I am the managing director of Lao New Wave Cinema Production and also the film director who wrote the script for Vientiane in Love, a gay love story that was banned in Laos last year. I almost always introduce myself as a filmmaker, especially since I don't consider myself a writer. True, I wrote my own movie but just because I had to. Writing is not really my passion, but I have to do it in order to have a movie to make. I am also one of the founders of Lao New Wave Cinema Productions. There's a feeling of urgency or maybe even impatience when it comes to the burgeoning Lao film industry. In the decades since the Vietnam War era, filmmaking in the Lao People's Democratic Republic was strictly for propaganda efforts under the purview of the government, but it was chronically hampered by a shortage of funding, resources and properly trained professionals.<9> Just so that you will know, we are now at the pre‐production stage of my new feature film, entitled Above It All, which will focus on LGBT and Hmong minority issues (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Movie Poster for Above It All

<10> Essentially—and I don't want to give away too much of the story—Noy, a male medical graduate who seems to lead a perfect life, is pressured by his parents to marry his beautiful rich girlfriend. When he can no longer deny and hide his sexual preference, he risks the consequences of telling his parents the truth. At the same time, a Hmong woman also named Noy and who comes from a poor family in Xiengkhouang province, looks forward to celebrating her graduation after a long struggle to support herself in Vientiane. However, her parents' arrival brings not the joy she expected, but the need to decide whether to remain in Vientiane with her musician crush or get married overseas in order to repay her parents' debt. This time around, the script has been written in a very light and careful way that we can nearly get approval for shooting, so hopefully it will be the first Lao film that can really show the existence of and the fluidity of gender differences in mainstream media.

<11> LEON CHEO: I was born and raised in Singapore and studied film at the first film school there. I have made several short films, the first two, "Four Dishes" and "Swing," were LGBT‐themed. Both had their world premiers at the San Francisco International LGBTQ Film Festival.

Figures 7 and 8. Film Poster for Four Dishes and Swing

<12> My short films have travelled to festivals in San Francisco, Hong Kong, Tehran, Bangkok, Germany, Tokyo, and more (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 9. Film Poster for The Three Sisters

<13> The Three Sisters won Best Short Film at the 7th NETPAC‐Jogja Asian Film Festival (Figure 9). I just finished a new short, Move Out Notice, as well as a web series, People Like Us. Currently I'm developing my debut feature film.

<14> LOUISA WEI: I am a documentary director, but also an academic who chose women's cinema and female directors as one of my main areas of research as early as 2001. I was motivated from my realization that women directors have often been omitted from film history. I always consciously include gendered perspectives into my work, but my feature‐length film Golden Gate Girls (2014) is the first work to focus on a queer subject: Esther Eng (1914‐70), a San Francisco‐born woman who became Hong Kong's first female director in 1937. My film is not only about Esther but also about her time, when Hollywood only had one female director, Dorothy Arzner, who was also lesbian. Stories about Arzner are intertwined with Esther's as well as are racist encounters faced by the actor Anna May Wong, whose life stories were mostly celebrated by gay artists in the 1960s and 1970s.

<15> WREN: Is there anything else that you might want viewers to know about you and your work? For example, how did you happen to undertake such a work?

<16> Anysay, how did you get into filmmaking? And how do you choose what type of films you make?

<17> KEOLA: It started when I was studying in Australia. I got my bachelor's in multimedia systems. There was one assignment that I had to make a short film for, demonstrating basic visual effects we had learned. The feeling when I watched my own work on screen for the first time left quite an impression on me.<18> After I graduated, I worked as a Multimedia Designer for Environment Operations Center in Bangkok, Thailand for two years. During this time I discovered that I'm not a salary/office type of guy, and my interests at the time were music and making movies. I spent most of my free time taking DJ music courses and filmmaking workshops. After I considered pros and cons of these two different fields, in the end I decided to focus on film making. With my family's encouragement, I studied for my Master of Arts in Film, from Chulalongkorn University in Thailand.

<19> My favorite genre is the thriller-like Seven, A History of Violence, and Old Boy. I grew up watching a lot of Thai films, Hollywood movies, and more recently I have discovered how brilliant Korea's thrillers are. Therefore, my films represent a combination of Western and Eastern thrillers. It doesn't mean I'll only produce or direct a "dark film," but it really depends on what inspires me at the time and what message I want to deliver.

<20> WATERER: I have to agree with Anysay. In fact, my short film YOU CAN'T CURRY LOVE was in part inspired by a decade‐long obsession with India's Hindi‐language "Bollywood" cinema—the colors, the music, the gorgeous actors, the costumes (Figure 10). I wanted to try to capture some of that magic in a short while also exploring the extremely timely issue of homosexuality in India, which was for a time decriminalized there and then recriminalized soon after.

Figure 10. Film Poster for YOU CAN'T CURRY LOVE

<21> Most of the very few images of gay South Asians on film have to date been stereotypical, tragic or negative. Hopefully my film's uplifting love story will help counter that, and also help enlighten people about the difficulties of living in India as a gay, lesbian or transgender person. But I also wanted to explore the struggles of Non‐Resident Indians to try to reconcile their ethnic background to their sometimes highly Westernized personal identities.

<22> I conducted significant research in order to write this film, including a trip through India, and a number of interviews with both gay and straight South Asians. I then collaborated with the actors to create the final script. I hope audiences have and will enjoy the short every bit as much as I've enjoyed discovering the magic that is India.

<23> WREN: And do you have anything to add, Leon?

<24> CHEO: Well, I just want to make it known that Swing was made during my two years at Chapman University in Singapore. It began as a class exercise in making a film with a 3‐page script, 2 actors in 1 location. The film was inspired by something my first boyfriend said, that he would remember us forever. I agreed to do so as well. As time went by, I questioned that notion and wondered was it possible as I found myself slowly forgetting. For the longest time, the film's working title was Before I Forget.

<25> WREN: Are there particular techniques you use in making short films that you believe best characterize or set you apart from others? Here is a chance to define yourself—maybe even take a risk at self‐promotion, if you would.

<26> WEI: I am one of the very few independent documentary filmmakers in Hong Kong who specialized in dealing with historical subjects and in writing forgotten figures back into history. My first documentary, Storm under the Sun (2009) was co‐directed with my colleague and friend, Peng Xiaolian, and was the first doc to reflect upon Mao's purge of writers centering around the 1955‐56 Anti Hu Feng campaign. Golden Gate Girls, which is now distributed by Women Make Movies in North America, is already recognized by feminist scholars for its effort in writing a female film pioneer back into women's film history.

<27> CHEO: In the context of Singapore, I try to eschew what I usually see in the short films there. Singapore filmmakers are very nostalgic; I can be too, but I try to do something different or run away from that. In The Three Sisters, I broke the fourth wall and made the film self‐referential. In Swing, there is talk of the past, but we never actually get to see the photograph.

<28> KEOLA: As I said earlier, I have to write my own screenplays because in Laos, we have lack of writers, and especially screenplay writers. I develop my script by interviewing my gay friends, and Hmong ethnic experts, and by consulting early with the cinematic department with the government, just so that I was aware just how far I could go in presenting what many might see as "sensitive issues."

<29> WATERER: One technique I use in creating short films that I hope will stand out is to put a strong focus on three areas many short films tend to neglect—locations, production design, and costuming. Film is a visual medium and a huge part of the experience that I always enjoy as a viewer is being transported to another place. By creating or choosing aesthetically pleasing locations filled with eye‐catching but accurate details, I help the viewer be immersed in the world of the story. Choosing costumes that define the characters and the worlds they come from and inhabit enriches the storytelling. As a director, I feel that these tools are hugely underutilized in a majority of shorts. Because my filmmaking style tends to be fairly restrained in terms of visual flourishes, I value the content of the frame itself quite a bit.

<30> KEOLA: The film Above It All, as many may already know, is my second feature film. With this film I applied more realism in the cinematic language to this film. I mean, I see it as drama, and I want audience to feel more "real" and less manipulated as, say, with soap operas. I think it is fair to say that I may not yet have my own signature. I'm still learning with each movie. Obviously, I have grown as a director since my first work with At the Horizon, and I'm now quite open to try new things with future movie projects.

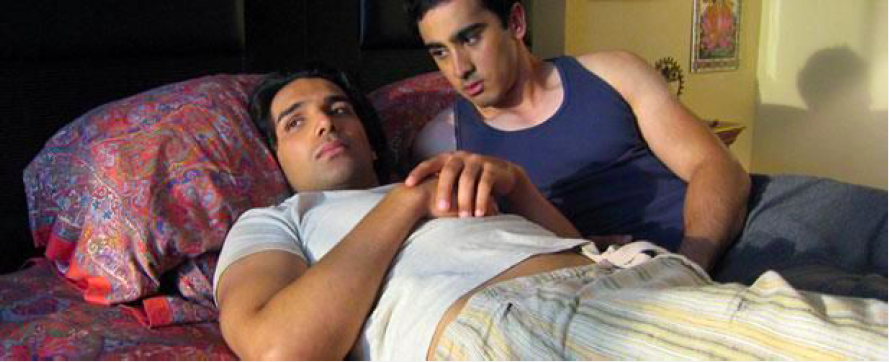

<31> WREN: I am curious about the background to your screenplays? Do you develop them? Or were they found or written especially for your film? How difficult was it to locate a suitable storyline for your work?

<32> WATERER: Before my visit to India, I had formulated some ideas about the general structure of the storyline. I knew that I wanted it to be about a highly Westernized person of Indian heritage being transferred to India for work. I loved the idea of someone feeling culture shock in the culture of their own heritage.

<33> I had done quite a bit of research already, but I chose to wait until after my visit to write the script because I wanted it to be informed by some of the actual things I saw and experienced in India. The encounter with the begging transgender hijra was added to the story because a similar event occurred during my travels and I found my taxi driver's reaction to the hijra fascinating, as well as the hijra's aggressive tone asking for money. Additional research after returning home made me feel obligated at least to touch upon this interesting subject in the film.

<34> The script evolved further during the audition process. Meeting with dozens of South Asian actors, many had stories to tell that led to revisions and corrections in the characters I had originally written. Finally, once my four South Asian actors were cast, their feedback and suggestions were invaluable. Rakshak Sahni was especially helpful as someone who was born and raised in India, and who had lived there until only a few months before shooting.

<35> CHEO: To add on to what I mentioned early, yes I wrote the screenplay based on something I personally had experienced. Though, I did not have a romp in the park with the ex. (laughter) After Four Dishes, I wanted to continue making more gay short films, and the class exercise presented the opportunity.

<36> Being at a branch of an American college, despite being located in Singapore, I faced no issue of content restrictions. Singapore filmmakers also need not get a permit to make a film. It is unlikely though that the Singapore Film Commission would fund a LGBTQ short or feature film. Censorship (or "Classification") happens later, for public exhibition.

<37> Some gay films are okay with the censorship guidelines in Singapore. Films like Ang Lee's Brokeback Mountain (2005) and Gus Van Sant's Milk (2008), with Sean Penn, were uncensored, albeit they were slapped with a R21 rating. A general caveat for these LGBT films is that the gay characters often are unhappy or die in them. In Singapore's censorship guidelines, promotion or neutral or positive portrayal is not allowed. Recently, happier films such as Lisa Cholodenko's The Kids Are All Right (2010), with Julianne Moore and Annette Bening as a long‐time lesbian couple, and Barney Cheng's Baby Steps (2015), had a limited one‐screen release. A small step toward progress, I guess.

<38> WEI: My Golden Gate Girls is obviously non‐fiction, and I wrote the script. My script is based on my search for Esther's story by following her life travels from San Francisco, to Hollywood, to Hong Kong, to Hawai'i, and then to New York. I was able to construct a film as I accidently got hold of a large collection of her personal albums and film stills. Others also shared research with me, so I can verify and defend every detail mentioned in my script with a piece of audio and/or visual evidence: newsreel, photos, recordings, magazines, news clippings and the like. Her story is fascinating-I hope everyone will agree with me on this point-and my biggest challenge is to touch hearts with my telling of her story.

<39> WREN: That leads me to my next series of questions. How was the issue of casting handled? Did individuals come to you through an open audition? Or were they recommended? By friends and acquaintances perhaps? And can you say anything about each actor? How has your film served to launch their careers in film, for example?

<40> WATERER: Casting for the film was a major concern. I was adamant that I wanted the lead from India to have an authentic‐sounding Indian accent. I did not want a poor imitation by someone who had only heard the accent on television or from distant relatives then learned it just well enough to pass with Americans who wouldn't know any better. I also preferred to find an actor with a non‐American accent for my other lead as I feel that the Indian communities in certain specific countries like the UK are more fully entrenched in the highly Westernized culture there because of the historical connection. All actors were found through film casting websites. Actors submitted for the roles, auditions were held for promising candidates, and the cast was secured.

Figure 11. Vikas and Sunil in Bed

<41> Ashwin Gore, who played the film's lead role as Vikas, is originally from Australia. Although he wasn't the Brit I was originally hoping to find, he still had a posh quality and a very Westernized identity. He also gave a deeply felt audition that impressed me with his acting talent and access to his emotions. He was the ideal choice after that, and I never regretted having gone with him. Since the short, he has created and starred in two different web series and auditions regularly for larger films.

<42> Rakshak Sahni, the film's charming co‐star who played Sunil, was exactly what I dreamed of finding when I wrote the script. He had been the star of a popular Indian night‐time soap opera and had just moved to America a few months prior to the auditions with the hopes of making it in Hollywood. His charming sweetness, good spirit, and onscreen charisma, not to mention his good looks, secured him the role immediately. Sahni has also starred in several web projects since the shoot.

<43> Both actors have been bombarded with messages from around the world expressing admiration for their performances and gratitude for taking part in the project (Figure 11). Neither expected to develop a global fan base from appearing in a small short film but as the project gained recognition, so did they. Both tell me that they are extremely grateful for the attention and acclaim the short has brought them.

<44> KEOLA: In my case, I had to arrange an open casting call through Facebook, but in the end most of the main

characters can from networking with modelling and artist agencies. We don't really have a cinema industry in Laos yet, so nobody can come out and say,

"I'm an actor." So, what we have is a very unusual case, I think: most of our actors "act" for the experience and to expand the opportunity in their

own field of works, modelling and singing, for example. But in any case, they need other jobs at the moment if they plan to work in the entertainment

business, either as a hobby or for the supplemental income.

<45> WEI: To speak honestly, my experience is not so very different from that of Anysay. There are not many who still know Ester Eng. I picked a few scholars/historians and several friends of hers to be interviewed into my documentary. But there were few who were willing to tackle the work, of course in large part because my film is a documentary.

<46> CHEO: In Swing, there were only two actors, so it was relatively easy to cast (Figures 12 and 13). I had an open

casting call and met a number of potential actors. Jin Li was in my previous short film, Four Dishes, and to be honest, I wanted to work with

him again. I saw Justin in another friend's short film. Right now, sadly, both aren't really acting anymore and have jobs in other industries.

<47> WREN: How has your work been received? Anysay, let me start with you: what has been your experience in Laos?

<48> KEOLA: So far, we have received good feedback, especially after the recent press screening in early December of 2015, but in truth the film not had its public release yet, so I have no idea about overall reactions. I do know from the initial screening that we need to have some edits—this according to comments by the authorities with the government. One thing is for certain: I will be very busy over the next few weeks getting the work ready for a public showing.

<49> Louisa, what has your experience been? I imagine many viewers welcome hearing the story you are telling, especially about such a significant female direction.

<50> WEI: After Golden Gate Girls ran seven screenings in HK and went to twelve international film festivals and toured over a dozen US and Chinese universities, thousands learning about her deeds (Figure 14). The film received predominantly positive responses, and scholars have been very enthusiastic about it. It has been the opening film in over ten international conferences, including one recently in February of this year. It is entitled "Esther Eng and New Challenges of World Feminism" and was hosted by Columbia University.

Figure 14. Anna May Wong

<51> And Reid, what about your work in India? Among Diaspora audiences? By others outside of the culture? Have you encountered any negative responses?

<52> WATERER: The short has received a real mixture of reactions though of course primarily very positive. Many LGBT people from India or of Indian heritage have expressed extreme gratitude to me. Sometimes I have encountered distrust from people due to the fact that I am not Indian, or because of the connotation in their head that the use of the word curry in the title is somehow connected to racism rather than just a fun wordplay. After people view the film, this distrust usually dissipates completely. The characters are not treated as anything other than likable, relatable people. The film is also a love letter to India. I carefully chose shots to accentuate its charm and beauty, and excluded many images that counteracted that impression. I did have one single strong negative reaction from a viewer in New York. This person accused me of being racist because the film shows a cow wandering the streets as well as a snake charmer, proof to her that I was trying to make fun of India. I explained that those shots represented the culture shock that my lead character Vikas feels upon his arrival in India. To be candid, those are the type of things many Westerners first notice visiting India because they are so different from anything at home. As the story progresses, the imagery changes very rapidly to beautiful scenery and lovely architecture. In discussing the film further, it seemed she had decided my motivations were solely cultural appropriation, and obviously connected me with a previous encounter she'd had with a coworker who she felt dehumanized Indians with a truly culturally insensitive theme party. I realize that with India's horrible history of British colonization, distrust of any Westerner claiming to be ally but meddling from the outside is sure to cause some alarm. I actually found the feedback thought‐provoking.

<53> I also deeply regret that the film was written and filmed years ago, just before I learned that the word "tranny" is upsetting to transgender people. I would never have had my lead character use it if I had known this then and I apologize to anyone viewing the film now. I meant it as an affectionate, inside, slang word with attitude. I have also heard the scene itself described as transphobic. It was inspired by an encounter I witnessed in India between my cab driver and a hijra. I meant for the character of Vikas to express surprise that hijras approached people in India so aggressively, visibly, and regularly, not be amused that hijras exist at all as some might have interpreted it. I failed articulating this character's reaction. I do hope people realize anyway that having a character express transphobia, or more importantly racism like the film's boss does subtly, does not mean that the film's writer has these views himself. As a writer I am trying to replicate what these specific characters, sometimes highly flawed, would say or do in the circumstances of the film. Luckily most people see the film for what it is, a love letter to beautiful India, its handsome men, its incredible music, its eye‐pleasing clothes and colors, and its wonderful culture.

<54> WREN: And Leon, has your experience been any different?

<55> CHEO: I was perhaps quite fortunate that my film originally premiered in San Francisco and has had screenings in Germany, Tokyo, India, Indonesia and more. So in general, I think festivals have liked it enough to program it. Sadly, I could not attend many of the screenings, just the one in San Francisco and those in Singapore.

<56> It really isn't a negative response but because of how Singaporeans speak English, subtitles tend to be necessary and is a common "complaint" I've experienced. The film is on YouTube and several people have said to me that they couldn't comprehend that particular showing. The best screening I've attended was Short Circuit, a night of LGBT short films in Singapore, which sadly, doesn't happen anymore. Singapore LGBT filmmakers need to make more films for ourselves. Some audiences didn't like that the film is so short or that it is a "slice of life". I think they wanted a full story and a proper ending. But that wasn't what I set out to accomplish.

<57> WREN: Might you share any interesting anecdotes, maybe amusing, awkward, difficult?

<58> WEI: Well, does Bruce Lee count? And no, I am not joking. Bruce Lee plays a baby girl in a 1941 film directed by Esther Eng: Golden Gate Girl. Of course, my film title with "girls" in the plural is a tribute to her and also to Dorothy Arzner, who was also San‐Francisco born. Few remember Lee for his performance, I imagine, save of course the photographic documentation left behind.

<59> KEOLA: I can't really think of anything amusing or difficult, and nothing awkward at the moment. I do want to emphasize, however, just how impressed I have been by how many Lao crew members have shown a genuine commitment to the project, especially by their willing to work not for huge sums of money—we are low budget project. While the crew has not had much by way of payment, they have nonetheless worked hard, to the best of their abilities, all to support my vision. I am greatly indebted to each of them for their hard work.

<60> CHEO: The crew, except the DP, was made out of my classmates so it was quite fun working with them. I'm not sure if it is interesting but the film was shot in less than six hours! One of the actors only had half a day so we just made it work. Unfortunately, near the end of the shoot, I tripped on a cable-Jim, you can stop laughing now—and damaged the lens adapter.

<61> WREN: My apologies. It just sounds so very familiar, like something I would do. Maybe like something I have done more than once.

<62> CHEO: Well, fortunately, the camera could still record video, so we continued with the filming. A damaged camera is no laughing matter!

<63> WATERER: Listening to others speak, I can now understand just how fortunate I have been. In fact, the most challenging aspect of my production, I have to say, was that all of the scenes of the actors, whether set in London or in India in the film, were actually filmed in Los Angeles. Finding locations in California that could double for India convincingly was a fascinating and difficult challenge.

<64> For scenic establishing images to begin each scene, I shot footage during my travels in India that is used all throughout the film. Among these shots are images meant to represent the impressions of a first‐time visitor to India, as well as exterior shots of locations designed to give the film a sense of place. I reviewed this footage extensively before shooting. The India shots I selected for the film were carefully interweaved with the footage of the actors in Los Angeles to try to seamlessly create the feeling of having shot in India.

<65> Our most difficult shooting day was the exterior scene in which the hijra approaches the leads and asks for money. When she leaves, they discuss hijras. We were filming in an alley in Los Angeles selected for its aesthetics. We had a permit from the city to shoot there. One family who lived in an apartment looking out into the alley claimed the shooting was a disturbance though most likely their motivation was the hope they would get a payoff for not disrupting the shooting. This is sadly a common occurrence in Los Angeles where there is so much big‐budget filming. We were a tiny cast and crew of maybe eight total, with no vehicles in the alley. When no payoff was offered, the residents decided it would be a perfect time to practice playing their drum set. Luckily we had filmed the dialogues enough times already that we were able to complete the scene, despite the soundtrack of the additional angles being ruined by the drums.

<66> WREN: Looking forward, where do see this film going? Beyond YouTube and Reconstruction, will it perhaps enjoy even wider release?

<67> CHEO: Swing is a little old and has traveled to a decent number of film festivals. It will likely stay on YouTube and Viddsee so that more people can watch it. Interestingly, because I used the same actor, people tend to view Swing as a sequel to Four Dishes. That wasn't my original intent. Still, perhaps I should make a third short film with the same actor to continue the story! I wonder.

<68> KEOLA: Obviously, I hope to have my film travel to as many film festivals as is possible. Of course, a number of factors come into play whenever a director decides to submit.<69> WATERER: When I made the short, my plan was to play it in film festivals then hopefully get it seen in India somehow. At the time of production, the site YouTube did not have nearly the global popularity that it enjoys now. It was not part of the initial plan. I had no way of knowing anyone in India would ever even become aware of the short though, let alone seek it out.

<70> As the short started playing festivals, word about it spread rapidly. Soon I was being contacted by people around the world but especially India who wanted to see the movie. At the same time, one of my actors had put a few scenes from the short online as part of his acting reel. People searching for the film found his reel and the view count kept rising. I realized then that YouTube would be a perfect platform to allow me to share this aspirational LGBT love story with the very people I had made it for, Indians who wanted deeply to see themselves represented onscreen. I was especially happy they could see it at no cost to them.

<71> Almost immediately, my posting of the full short began accumulating views. The viewers came not only from the USA, Canada, and India but also from countries like Egypt. I was excited to discover that the film had a universality, and that people felt connected to the protagonists regardless of the viewer's ethnicity. At this point, the film is rapidly approaching 4.5 million views on YouTube, last I checked. It has also screened in more than seventy-five film festivals on six continents and won audience and jury awards.

<72> WREN: I am intrigued. In your opinion, does your work accurately portray the reality of gay culture(s)? Are the scenarios believable, in other words? Does a notion of regional identity, for example, emerge within the work? Is it art imitating life? Or has life picked up where you left off?

<73> CHEO: If I might answer that. To an extent, Swing does portray gay life accurately. I wish people might understand that gay people just are: they don't harp about being gay all the time. I wanted to make a film in which being gay is secondary to what the characters are going through. And this is something that doesn't happen often in film, at least from my experience. Gay characters deal with being gay constantly-you know, with coming out, being closeted or falling in love secretly. I wanted to make a film where two people are falling out of love; they both just happen to be guys.

<74> WATERER: There is definitely an element of life imitating art at this point. I have seen quotes of dialogue from my representation of a gay romance in India used as reference in articles and discussions about life for gays in India. This makes me both proud and disappointed as obviously I'm neither an expert nor Indian. I had hoped the obvious demand for this short would in some small way help ignite a wave of storytelling from the Hindi film industry finally representing the LGBT community and its stories. Instead of a wave, it has been like a few drops. Even that is progress though, and makes me happy.

<75> KEOLA: My movie portrays several perspectives on gay culture in Vientiane-but in Vientiane only. Any gay culture is still very different and less acceptant outside of the capital city. It is also important to understand that this particular work only looks at the "clean" side of homosexuality in Laos. I have found it true that many people have shown their support for this movie. It is at least a small first step that we talk about gender equity in mainstream media, but remember that in Laos this is the first time that such a conversation has found acceptance.<76> I honestly don't understand your questions about regional identity, or maybe I just have not as yet thought about such issues. Or have I answered you by noting that everything happens in Vientiane and not outside the capital? Lao cinema, you understand, is still in its infancy. Still, several international critics have commented that with my film At the Horizon I have shown an interesting penchant for broad comedy and the conventions of Asian rom‐coms-slide‐whistle sound effects, bloody noses and all-with an amusing story about a photographer who earns his living by taking pictures of couples at the city's Patuxai arch monument. I find myself both appreciating and laughing with these comments. I am very humbled that my work has attracted that sort of close reading.

<77> WEI: I'd like to interject here, if I may. I believe the reception of gay cultures vary vastly across historical and other contexts. One mild critique I often make on discrimination today is to show how people were more open‐minded in the 1930s. From what I learned, Esther lived her life without any shadow over her status, but rather, she was a celebrity for what she was. I guess this made her unique, with the unique circumstances, the Sino‐Japanese War, for example, where independent and capable women were really appreciated. The success of her restaurants in New York City from the 1950s to the 1960s, especially with star customers like Marlon Brando and Anna Magnani, was also possible with her finding the ideal location and ideal community.

<78> WREN: Within your larger career as a whole, where does this work fit? Have you found it a positive factor in developing additional works? And what is on the horizon for you? Any other explorations of LGBTQ films in other regions?

<79> WEI: I have made a lot more LGBT friends after making Golden Gate Girls, and since I am always interested in people who cross various boundaries, I am sure I will be able to present or touch on related subjects.

<80> KEOLA: I look forward to developing new projects that fit my interests in realistic depictions of relevant social issue, at once chilling and entertaining. It cannot be said enough, however-and I think most filmmakers would agree—finding funds remains a significant challenge for every filmmaker, but I am determined that I'll still keep making films. In my particular case, when there is funding for me to explore another LGBT issue, then I am up for the challenge and will challenge myself again. I have to say, with all honesty, it is just a matter of whatever opportunities that I may have in future.

<81> WATERER: As a fellow director, I know exactly what filmmakers must endure to get a project off the ground. I admire Anysay for his dedication and determination.<82> I personally have continued to make short films that play the LGBT and mainstream film festival circuit. My follow‐up short was actually inspired by the fact that both actors who play the leads in YOU CAN'T CURRY LOVE are heterosexual. I made a comedy about two straight actors cast in a major feature film which includes an extensive gay love scene and their unusual methods of simulating attraction and convincing male‐to‐male contact. This short has played over fifty film festivals. I also did another short with a similar feeling to YOU CAN'T CURRY LOVE, this time about an American visiting the Mediterranean on vacation and attempting to navigate the unknown opinions and customs of locals as he struggles to figure out who he should and shouldn't tell that he's gay. That one, FOREIGN RELATIONS, is currently playing festivals.

<83> As a result of the success of several of my shorts, I was approached by a LGBT video distributor about releasing my work through their companies. I am quite honored, as this is a rarity for a short film director.

<84> I do hope to either make a sequel to YOU CAN'T CURRY LOVE or else to expand it into a feature length film. There are so many other areas to explore, especially with the current court battles in India about the legality of homosexuality and the recent recognition of transgender individuals as an official third gender. I'd also like to explore the experience of LGBT people of Indian origin in either the United States or the United Kingdom. There are many extremely talented South Asian actors typecast in dull, sexless, repetitive roles here in Hollywood who I know would shine in a passionate love story with meaning. Ideally the Hindi film industry will make it unnecessary for me to have to make such a movie, but until then I will continue my efforts to get another such film made.

<85> WREN: Is there anything else you might like to add as we bring this round table to a close?

<86> KEOLA: I really want to thank you for taking the time to discuss my work here. I appreciate your time and patience as I have address4ed what I saw as some of your concerns with Lao film.

<87> WATERER: Well, I do want to thank you and everyone around the globe who has supported YOU CAN'T CURRY LOVE. I hope the short has given a fraction of the joy to those who have viewed it as their positive feedback has given me.

<88> CHEO: It comes as no surprise, I think, that Swing remains one of my favorite works. It is something that brings

back good memories. Because the film made its way into several festivals—it was such a simple short film. I am really happy that it has

traveled so far. The film makes me want to continue with making such films that genuinely connect with people on an emotional level. Recently, I made a

gay web series set in Singapore. It will be out soon, and I really hope people in Singapore and around the world will enjoy it. I am, rightly so, I

believe, very proud of it. Right now, I am working on the writing for my debut feature film. Still, I would love to make a LGBTQ feature film, as well.

So let's see.

<89> WEI: My particular film has not been, although it should have been, to many queer film festivals. It has been received well at the Paris and Beijing lesbian/queer festivals. In China, Esther has already become a new gay icon. Hopefully, she will be known by larger and larger LGBTQ audiences. She certainly deserves to be recognized.

<90> WREN: And on that positive note, I believe we have come to an end, at least for the moment. Again, I want to thank each of you for your many compelling insights. I am certain we have all learned something about the state of filmmaking and LGBTQ representations. It is a difficult and complex subject, I think everyone will agree, and there is much work yet to be done as opportunities for directors, writers and actors increase across Asia. It is my sincerest hope that each of you will continue to find much success with your work. Thank you again.

Return to Top»