Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 2

Return to Contents»

Concealed Fears and the Hypermasculinity of Contemporary Korean Gendered Society: Kim Jho Gwangsoo's Just Friends (2009) / JaeWook Ryu

Abstract

Just Friends, as director Kim Jho Gwangsoo's second attempt at filming gay representations and the realities of their personal lives, explores both the fear behind having gay identity revealed and the hyper‐masculinity esposed by a heavily gender‐restricted society in Korea that serves to make the anticipation of imminent revelation always dreaded and emotionally painful for all involved. At the same time, the film creates a place for gay sexuality and, in doing so, suggests that personal realities need not be defined from without. Instead, as the final musical sequence demonstrates, reality can be determined by and mediated through individual choice.

Keywords: Kim Jho Gwangsoo, Just Friends, concealed fear, distance, hyper‐masculinity

<1> Just Friends (친구사이 Chingusai, 2009) is only the second short film by Korean director Kim Jho Gwangsoo (1965), who had promised in the wake of his first short queer film, Boy Meets Boy (소년, 소년을 만나다 Sonyeon, Sonyeoleul Mannada, 2008), to release one queer film project every two years. In fact, most of his queer films-and this is true for queer and feminist films alike-were seen as investments by the non‐profit Chin‐Gu‐Sa‐I, one of the largest gay rights organizations in the country. [1]

Figure 1. The Opening Title Wedged Between Duplicate Symbols of the Masculine

<2> According to his interview following the closing credits to Just Friends, Kim has been encouraged time and time again to direct his attention toward gay issues. As if he were telling a fairy tale with his first short, Boy Meets Boy, he presented as possible that adolescents in the absence of any sexual contact might on a platonic level fall in love. Just Friends, however, would prove far more confrontational in approach, as he focused on the real‐life experiences involved with compulsory military service and the issues surrounding "coming out." Both are scenarios young Korean gay men face as yet another stumbling block erected by an oppressive social system. Indeed, Kim asserts that he wanted to focus on youthful emotion and affections not as a vehicle by which someone might reveal his authentic self as gay but to make concrete the thoughts, feelings and life events shared by all young men at this time. That said, the work manages to illustrate the invisible fears that confront the LGBTQ communities daily, in particular as they sense the increasing need to conceal their true identities from the prying eyes of a gendered and gender‐conscious society.

Between Reality and Fiction

Figure 2. The First Musical Sequence as Min‐soo Sings

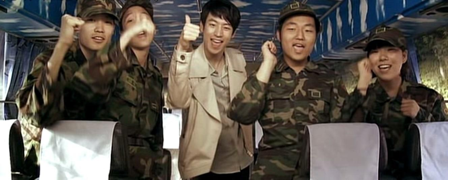

<3> Just Friends begins as the opening title is revealed to two symbols of male sexuality, stood to balance each other (Figure 1). As the title fades, Korean traditional trot music with its fast and lively rhythm starts. We see a young man in the aisle between seats on a bus. In a framed full shot focused on the center of the bus, we see Seok‐i (Lee Je‐hoon) singing romantically. Another young man wearing a military uniform, Min‐soo (Yeon Woo‐jin), joins in unison. As a musical sequence unfolds, other characters in uniform join the performance (Figure 2). Suggesting the nature of the plot through their lyrics, they promise they will love each other forever. More to the point, revealing a gay love story in the first sequence is tantamount to the act of "coming out," as the audience is told that is a queer.

<4> We encounter music again later in the church sequence, where the lyrics function oin a narrative level as Min‐soo's confession and subsequent apology to his mother (Lee Seon‐joo): "I like a guy. Please, understand me. I have no regrets. I am sorry." Many of the arranged scenes are riddled with various emotions as mother and son interact. Interwoven throughout are Min‐soo's memories, hopes and dreams as he pleads for understanding from her. His confrontational smile at Jesus while in the church scene suggests a fantasy and a world at one remove from reality.

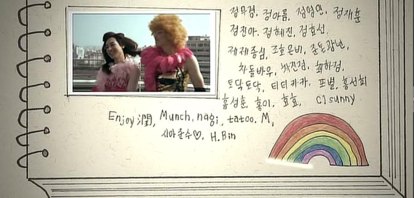

<5> Unlike the two earlier musical sequences, the final sequence with the closing credits aggressively reveals the queer nature of the subject matter, in particular as Min‐soo and Seok‐I appear in drag, dancing and singing in a wide‐open space. Music and lyrics identical to the first, in this instance the impetus shifts as any direct and tangible associations with previous events are erased. However much the film has to this point discussed a personal gay reality, the final number serves in many ways to restore a sense of unity and harmony between film and audience, as the audience is invited into an imaginary reality framed in sound and performance. Equally true, the distance between queer subjects in the film and homophobic perspectives from without serves to hide larger political implication inscribing the close‐ups and long shots that carry the actions forward.

The Boundary between Revealing and Concealing

<6> While Seok‐i sits on the bus on his heads to the military base to visit his boyfriend, he is accompanied by a woman sitting next to him. The dialogue that ensues betrays a certain irony inherent to military assumptions concerning masculinity, as the young man explains that he is on his way to visit his "lover." In the absence of any further revelations of personal sexual orientation, spectators might fail to comprehend that his lover is male. But as a gay man, Seok‐i is attuned to the course of events as they might naturally unfold and realizes that he has made a mistake in choosing his words carefully. From his perspective, the term lover can only refer to one person, his boyfriend. Although the woman remains unaware that that he is gay, his revelation in such an open public space as a bus only further adds to his fear of exposure.

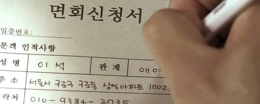

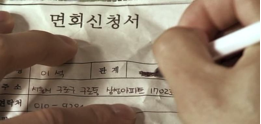

Figure 3. Writing "Lover" in the Space Provided

Figure 4. Min‐soo's Disappointment

Figure 5. "Lover" Crossed‐out

<7> Just Friends, in fact, makes full use of close‐up shots to focus the attention of viewers on certain objects, among them the emotional changes in the faces of certain characters. Others hint at the secret nature of love and to gay identity, in contrast to the use of a long shot/full shot to capture the background of scenes. All come together to give expression to the invisible pressures under which Korean gay men must function in order to protect their identity. conceal their identity.

<8> In one such shot, we watch as Seok‐i fills out the visitor's application form. Here, the camera captures the application form in a close‐up. Without having thought his actions through, Seok‐i writes the word "lover" in the space provided in order to clarify the nature of his visit and his relationship with the soldier. Almost immediately, he then writes "friend," having crossing out the first word with his pen. He grows embarrassed and disturbed with himself and requests a new form. Important here are the sequential shots that frame his wrinkled application paper and the consternation and sadness now apparent across his face (see Figures 3, 4, and 5).

Figure 6. Framed Feet Beneath the Desk

Figure 7. Bearing Witness to Gay Identity

<9> Later, as Min‐soo visits Seok‐i in the visitors' room, the camera focuses on their feet in contact with each other under beneath the desk (Figure 6). This close‐up functions in two distinct ways. First, it underscores the harsh reality of their relationship and that they must keep their gay identity somehow "beyond" open spaces. Second, it announces as it betrays their true feels for each other in a concrete manner that others will understand, as does the woman who travelled on the bus eartlier (Figure 7).

<10> In contrast to close‐up shots, the film sometimes relies upon full shots and long shots to indicate the expanse of-and the imminent threat inherent to-an open space before resorting to the particular details in close‐up shots. Between repetitive use of close‐ups and long shots, Just Friends creates an invisible boundary between concealing and revealing, comparing images that the shots create. Thus, the film locates and isolates the young men in open spaces, placing them precariously so that others might watch-oversee-their behavior. Seldom are the absolutely free from the gaze of others to be themselves.

Figure 8. Three Together at the Inn

Figure 9. Three toothbrushes and a Military Cap

Figure 10. Uniform, Street Clothes and a Coat Hanger

<11> Following the sudden appearance of Min‐soo's mother alongside the sounds of the young men off‐screen, their relationship begins to resemble that of friends engaged in dialogue with her mom. Any open discussion of their feelings occurs, ironically, in another open space, on the street in front of the inn. The expanse provides the only possible place where they might avoid Min‐soo's mother. Likewise, the full shot of their conversation exposes a larger reality, that they must at all costs hide the nature of their relationship even from members of their immediate family. Transitional shots-of three toothbrushes in the same cup and two outfits hanging in layers on a single coat hanger-and a medium long

shot placing the three characters together on the floor (Figure 8, 9 and 10) further underscore the awkwardness in their being together.

Figure 11. Min‐soo's Mother as Witness

Figure 12. Distance Between Mother and Two Protagonists

Figure 13. Barbed‐wire Entanglements as a Boundary

<12> As Min‐soo's mother as a devote Christian makes her way to the local church, a moving medium long shot follows the young men as they return to the inn and its expectations of privacy to engage in sex. The following shots "describe" in detail their behaviors as a series of close‐ups. The camera frames even as it creates an increasing tension, as we move from the mother to the young men, separated only by a series of transitional cuts that compound the sense of fear their identities are about to be revealed. A distance between each figure characterizes as it underscores both the strain and the imminent conflict and the alienation and disenfranchisement that will almost certainly result. Furthermore, in the transitional shots (Figure 11, 12 and 13), the immense distance captures as it betrays a larger reality, that they are quite literally stuck in the prison behind the background of barbed‐wire entanglements.

Figure 14. Min‐soo in Silhouette

Figure 15. Mother's Tears at Home

Figure 16. Min‐soo's Confession from His Point of View

Figure 17. Jesus Smiling at Min‐soo and His Mother

<13> Having revealed their secret to the audience at precisely the same time that the mother sees all, the camera follows behind mother and son, capturing them in a single long shot. Woven together in a larger clothe of Min‐soo's making (seen from his point of view, after all), additional full shots create a larger image of the past, a time when they had shared good times together and had enjoyed each other's company. The camera the forces our attention elsewhere, in a close‐up of the smiling Jesus, suggesting at least momentarily all love benefits from his downward gaze (Figure 17). The mother's prayers are then captured in a single long shot that extends the reaches of that love.

<14> Although no maternal perspective dots in the narrative landscape, the film nonetheless demonstrates that the mother can embrace their love and through an increasing understanding of the situation can identity both forgiveness and love. The pattern of several long shots and close‐up shots mirrors that of the musical sequences, but instead of restoring a sense of balance, unity and harmony, the nature and the ambiguity of the invisible boundary between revealing and concealing is made clear. Betrayed by the visual, Min‐soo resorts to narration as revelation of his authentic self. And at precisely that moment, both close‐up and long shots lend credence to his reality, including his gay identity. Thereafter can the young men walk hand‐in‐hand along the street in long shots. Only now are they able to embrace and kiss among a crowd, and their freedom is captured in a single close‐up.

<15> Between close‐ups and long shots, meaning is clarified, as the director makes clear the invisible boundary between concealing and revealing. The camera frames the difficult reality for gays in Korean gendered society. Long shots, for example, contribute to the larger sense of marginalization and disenfranchisement, while close‐ups isolate the individual further with an intensity akin to public scrutiny. In heteronormative society, the queer individual must conceal the truth of self‐identity from fear of discrimination and exclusion. But there is more to the mechanism that is perhaps first apparent. Close‐ups can be explained as emphasized and magnified images rendered in isolation from earlier long shots. Thus, any sense of boundary arises from an intentional act at editing, underscoring that any perceived boundary between homosexuality and heterosexuality has its origins in fixed conceptions of gender and sexuality. This point is made clearer with Min‐soo's confession and apology or later in the closing sequence as the lovers consciously embrace an alternative reality and dress in drag.

Gay Reality and Gendered Society

<16> Underscoring the nature and dimension of Korean gendered society, certain spaces are presented from different angles and under different lighting. These spaces, so isolated, further regulate identity. In the sex scene at the inn (Figure 9), lighting focuses the embarrassment. It also emphasizes the mother's despair, as we sense the emotional pain she experiences-this in spite of the fact that she is lit almost entirely in silhouette by the light emanating from within the room. The silhouette of Min‐soo as a soldier, in fact, conceals his identity as it represents his precarious position on base (Figure 14). In a similar manner, the manipulation of lighting isolates an image of the mother, as she cries in the living room, her emotions depicted as they are revealed through the shadows (Figure 15). Or in those scenes on the street and in the church (Figure 13 and 16), soft natural lighting of scattered sunlight emphasizes the emotional tension between characters. Such effect is reserved for those moments when gay identity is laid bare for all to see. In contrast, harsh frontal lighting is used to exclude shadows, as the objective reality is rendered distance, clear and difficult on the eyes.

<17> At this point, it is perhaps helpful to recall that, in order to enter compulsory military service, all Korean males underscore physical and

psychological testing. Homosexuality from the perspective of those conducting such examinations continues to be treated as a mental disorder (Lee 2010;

You 2006). Revelations of homosexuality, however, are not sufficient to disqualify someone from service. In fact, the Korean military has yet to issues

of sexual orientation, and there is little to no data on homosexuality in the military system. In the absence of supporting data, the system

perpetuated the myth that homosexuality do not exist in Korea (You 2006).

Figure 18. Kiss in Front of the Stature of General Lee

<18> Although this film does not delve deeply into practical concerns related to gay issues, the focus on the military base as a particular space within Korean society serves as the backdrop against which larger issues of hyper‐masculinity are exposed. Consider, for example, the kiss at Sejong‐Ro, notably in front of the statue of General Lee Soon‐sin (Figure 18). The kiss itself erects a challenge to preconceived notions of Korean masculinity and the prevailing hyper‐masculinity that is imposed from authoritarian figures above. The location is important as a political space in modern Korean society-and places these young men in close proximity to Chung‐Wa‐Dae, the House of the Korean President. Their actions an incontestable statement that homosexuality does exist in Korea opposes any sense of hyper‐masculinity understood with having donned a military uniform. Regardless of the distorted view towards homosexuality held across Korean society or espoused in the Korean military, a single kiss is enough to establish a new reality (Figure 19). There can be no space without its gay identity.

Figure 19. The Musical Performance in Drag

Cast and Crew of Just Friends

Director: Kim Jho Gwangsoo

Min‐soo (Yeon Woo‐jin)

Seok‐i (Lee Je‐hoon)

Min‐soo's Mother (Lee Seon‐joo)

Chae‐eun (Lee Chae‐eun)

Sergeant (Moon Seong‐kwon)

Visiting Center Soldier (Son Cheol‐min)

Restaurant Owner (Go Soo‐hee)

Bus Soldier 1 (Im Ji‐hyeon)

Bus Soldier 2 (Ojeki Sinya)

Ticket Office Worker (Lee Chun‐hyeong )

Acknowledgement: Unless otherwise noted, all images were acquired under a Creative Commons license.

NOTES

[1] Just Friends had its world premiere at the 14th Pusan International Film Festival on October 10, 2009, and was theatrically released on December 17, 2009. Prior to its release,however, the Korea Media Rating Board rated the film's trailer as being "harmful to youth," and grading it as "teenager restricted" (19+), citing "sexual situations" and "risk of imitation." The following year, in September 2010, after extensive litigation, the court ruled that the film "provides understanding of and education about minorities."

Works Cited

Just Friends. Dir. Kim Jho Gwangsoo. 2009. Film.

Lee, Sang‐kyoung. "Constitutional Re‐ examination of the Military's Exclusion of Homosexual Soldiers: Focusing on the Federal Courts' Decisions on Constitutionality of 'Don't Ask.'" Journal of the Korean Branch of International Association of Constitutional Law 16.2 (2010).

Seo, Yu‐kyoung(2011). "Political Contribution and Limitation of 'Performance Politics' of

Judith Butler." Korean Political Science Society 19.2 (2011): 31‐36.

You, Ji‐Eun(2006). "Homosexuals in Army, Rights Issues in Army." Kookmin‐Ilbo (2006). http://media.daum.net. Accessed on 15 January, 2016.

Return to Top»