Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 2

Return to Contents»

Hot Boys, Their Bodies, and the City in Vũ Ngọc Đãng's Lost in Paradise (2011) / Nguyễn Quốc Thành

Abstract

This essay addresses two questions about the importance of filmic technique in Vũ Ngọc Đãng's Lost in Paradise (2011). In particular, does the physical body itself perhaps serve an additional function insofar as it provides a special layer, a lens of a sort, through which we are to view larger issues of urban space? More to the point, how are such spaces filmed and how does technique add to our understanding of the unfolding process of self-identification of gay men throughout the work?

Keywords: the male body, self-identification, urban spaces, knowing

<1> In the first scene of in Lost in Paradise (Hotboy nổi loạn và câu chuyện về thằng Cười, cô gái điếm và con vịt; hereafter Paradise)[1], under the direction of award-winning Vietnamese director Vũ Ngọc Đãng (1974- ), the camera follows a character we can only guess is a young man, as he walks down the street. Filming from an unusual vantage point, it focuses on his waist as it frames his body. While the movement of the camera is suggestive of a tracking shot-a shot in which the camera is mounted, for example, on a wheeled platform that is pushed on rails while the picture is being taken-the framing is clearly different. It is cramped, restricted; it limits our view. All we see is a faceless male body that moves and, at the same time, fills the center of the screen. As the body obscures the character's surroundings, it becomes the scene itself. Does this mean that a body also functions as a special layer, a lens of a sort, through which the audience might view larger depictions of and issues inherent to urban space? To answer this question, it is perhaps helpful to consider how the director films and frames gay male bodies, suggestive as it is of the urban spaces we encounter in Paradise. A similar question immediately comes to mind: how are such spaces filmed and how might technique add to our understanding of the unfolding process of self-identification of gay men throughout the work?

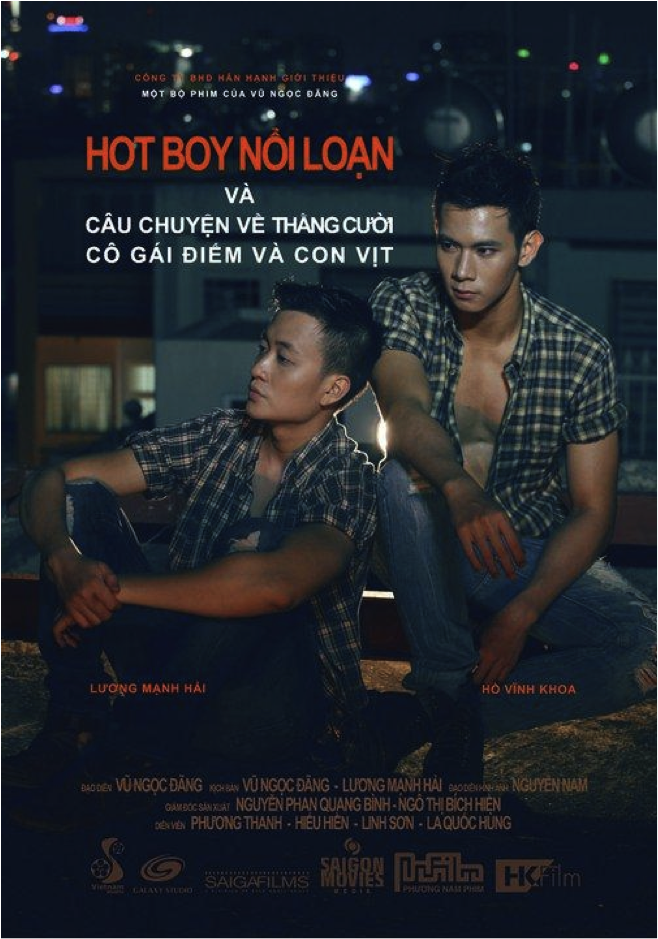

Figure 1. Movie Poster

<2> In the opening scene of this work, for example, whereas a male body "becomes" the scene, a special mise en scène expands around that body. The character carries a light travel bag and holds a city map in one hand. The map appears as little more than a bright, contrasting area of space at the center of the screen. We see it move and quiver near the fly of his trousers; in turn we catch a glimpse of what has until this point been hidden from our view as he walks. The emerging image is at once as thrilling and arousing as it is awkward and unnerving. What are we really looking at? What do we really want to look at? The map or the fly? Does the map, in effect, help us to locate first the fly and under it our destination, the genitals? Are we left disturb or embarrassed as we stare at the crotch isolated and exposed to view, or might our eye somehow be averted, preventing us from exposure and allowing for our escape from it? What precisely is it that excites, attracts and, yet, limits our closer scrutiny? The visual effect of a bright flat surface moving on the screen? A naïve curiosity about the genitals? And are the genitals actually male? Questions abound as the image unfolds.

<3> In Histoire(s) du Cinema, Jean-Luc Godard comments suggests that the ubiquitous Hollywood "medium shot"-in which the subject is in the middle distance, permitting some of the background to be seen-always frames men at the belt, "all because of the gun, therefore the genitals" [2]. In Paradise, a map replaces the gun; an object that provides directions replaces the overt, and suggestion replaces representation. More to the point, there are three notable absences in this scene. The first is the face, opening up a larger space of ambiguity concerning the gender of the character. The second are the genitals, precisely where our view has been directed but where social convention has forbidden us from looking. It is, in truth, a view that cannot be fulfilled. In fact, the lack itself becomes the representation. Vũ Ngọc Đãng's camera invites us to look at what we know we cannot see. Simultaneously, it makes it impossible for us to see the very representation of what is impossible to be seen. The camera plays with impossibilities, with our collective imagination about the specific attributes of the sex organs beneath the clothes, and with our uncertainty about kind. This play takes place in our mind even as it unfolds in front of our eyes: the special arrangement of the body changes and repeats in cycles of "seeable" and "unseeable," both suggesting and hiding the object of our desire. Put differently, the body is constructed as a site for a playful exploration where what we find becomes, essentially, the voyeuristic pleasure of seeing.

<4> That this depersonalized individual is Khôi (Hồ Vĩnh Khoa, 1988- ) becomes clear in a later scene. Having been thrown out of his parents' home, he has arrived in Saigon "as a young gay man fresh from the countryside, with an innocent and romantic soul, and then gets trapped in a fatal love affair with a man-a male prostitute." [3] The camera captures Khôi in the first few scenes as he moves confidently across various parts of the city. He remains fully dressed, up until he is about to be cheated out of all of his money. As this happens, Khôi's naked body is filmed from multiple angles and in a number of positions, collapsed on the floor in a private flat, exposed on a balcony for all to see, in each instance, helpless. His nakedness is suddenly made "available"-is given currency and circulated-only when he is left destitute. [4] From this point, the camera focuses on Khôi's half-nude, muscular body, on construction sites as he works as a physical laborer, under the shower, single or in a group among other workers. These exposed bodies are a matter of privilege, reserved only for us as viewers to watch (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Degrees of Exposure

A cruel paradox, these images are in stark contrast with the narration, where no one steals a glance at another body, where no one even mentions sex. The body of the physical laborer is rendered an object of desire, but its owner of that body-the worker himself-is striped of any sexual subjectivity. He himself has no possibilities of being the subject of desire. Neither is he able to become the object of desire for others.

<5> Not only is male-on-male sexual desire absent from those spaces where unskilled physical laborers live and work, but any sense of solidarity, the ability to support each other and any personal relationships between them, is nonexistent. Recall that an older, more experienced worker advices Khôi to leave the city and return home. Doubtless, his situation is similar, as a person who once came to Saigon from the provinces and who cannot go home under any circumstances. Their conversation, however, does not lead to further engagement between the two men. Certainly, co-workers might exchange information on prices of a rental, and such superficial exchanges lend themselves to a larger understanding of the brutal conditions under which male migrant workers struggle in the city. But they do nothing to further interpersonal relationships.

<6> In fact, the quintessential element that leads to meaningful relationships between the male characters in the film is related to gay identity. I will return to this notion later.

<7> Unlike that of Khôi, the body of Đông (Linh Sơn, 1987- ) is filmed, consciously so, with clear associations to an erect penis (Figure 3. Khôi and Lam).

Figure 3: Phallic Imagery

It stands, punctuated and erect, either in a vertical line, or it moves as if engaging in intercourse. There is no need for the camera to search for the genitals; instead, it moves further away and closer in, in and out and up and down, left and right, revealing every part of Đông's body. In effect, his body becomes a giant phallus for all to see. Just as important to note, these particular scenes take place in a space made for body watching and further lend to the growing sense of spectacle and the spectacular, on the gymnastic field in a city park, for example, where Đông is seen doing morning exercises. Looming large in the popular imagination, such fields remain a familiar sight in areas with high concentrations of young men-university campuses, army bases, or readily affordable apartment complexes. Here, men are free-permitted-to admire other male bodies, especially normative ones that are healthy and energetic, supple and muscular. Similarly, it is just as easy to watch male bodies engaging in erotic moves, as the camera lays bare Đông's physique. Under cover of competition, a healthy admiration is accepted, even required, as men are encouraged to put themselves in the position of an object of desire by other men. Such is the space where homosocial and homosexual desires converge.

<8> It comes as no surprise, then, that Đông finds Khôi near a gymnastic field. After a short conversation about the possibility of sharing a flat, the two walk together to Đông's place. Throughout this scene, sounds and dialogues serve to alter the physical space. This technique is repeated again in later scenes. In both instances, Khôi is "taken home" by another man, and both serve as crucial moments in the narrative of the film, at particular moments when the lead protagonist "expects" a turn in his fortunes in Saigon.

<9> We, too, expect a significant change in the story line.

<10> Consider the initial scene, where the camera peers down upon the city from above. People walking the streets appear miniscule in comparison to the streets and buildings around them. The image of a colossal ship docked on the river only adds to this sense of disproportion. As we watch this film, were we not to read the English subtitles, for example, we might fail to recognize that the two figures moving across the lower part of the screen are Đông and Khôi. Be this as it may, from high above, we can hear every word the two men say to each other. Physical distance is seemingly reduced to a few meters and ambient sounds, rendered silent, even as individual voices are intensified, magnified and made louder.

Đông: How old are you?

Khôi: I'm 20.

Đông: What are you going to do in Saigon?

Khôi: I don't know yet. I just wanted to find a place to stay and then I will see.

Their conversation is so very typical of people who have just met, those very people, for example, who have just arrived in the city. If there exists a border between the personal and the collective or shared, this scene blurs it significantly. Khôi and Đông could just as easily be anyone else. In this filmic reality, people are almost without notice, but their life stories can be recorded, down to the smallest of details. Sound serves to delimit a space where the private sphere is unleashed, enlarged and all-encompassing, where distances between a speaker and a listener are reduced, made miniature and insignificant. Not a single utterance goes unnoticed; every word is recorded, transmitted, distributed.

<11> Throughout this particular scene, the position of the various observers-be it that of the camera, the filmmaker or the viewing audience-is significant and remarkable. The scene is constructed in such a manner as to give the impression of a long shot in which the whole of an object is put on display in some relation to its surroundings. As observers, we depart from the same point as the characters do, they remain in our line of sight along the way, and ultimately we see them from a point very near their destination. Tellingly, however, we arrive before they do. We know where they are going. We know how their story unfolds, as if we have been in this road before. It is little exaggeration to say that, within this cinematic geometry, viewers and characters alike travel the same road, at the very same time.

<12> In another scene, the camera captures Khôi and Lam (Lương Mạnh Hải, 1981- ) from afar, as they traverse a walkway, the night sky their only backdrop. Again, the distance from the two characters is far too large for us to overheard them speak, but paradoxically we can hear everything they say. The peculiar degree of the inherent irony is made concrete in the significant distances-between viewers and characters, the observers and those observed-depicted within a single image. Khôi and Lam are elevated, thrust forward and into the center of the screen, both by the walkway and by the angle of the camera. Our line of sight places us as viewers standing off the road and at the bottom of the screen. They walk across the screen but clearly not to where we stand. What we overhear is a conversation between two people with shared experiences and similar backgrounds. And as they speak, they provide us with a definition of gay identity rooted in experiential knowledge, the criteria of which may be known to them only. Any discernible sense of the "Other" arises of necessity in images and dialogue alike:

Khôi: How do you know I'm gay?

Lam: I'm gay. I can just look and I know who is gay, who is not gay.

Khôi: Why did you decided to help me?

Lam: ...I thought your situation is similar to mine, when I first came to Saigon. The second reason is I need someone to live with, to fight the loneliness. You, too.

<13> Interestingly, the first question ("How do you know I'm gay?") takes place only after the two men kiss. Note that Khôi's question is not "Why did you kiss me?" Such a response would betray personal emotions and desires and would call into question how personal decisions are made. Instead, "How do you know I'm gay?" depends in large part on two words, "know" and "gay." Both Khôi and Lam know exactly what "gay" means, what behaviors are expected from gay men, and what behaviors are not permitted. Following this line of logic to its expected end, Khôi is convinced that Lam will "know" that a gay person will not protest, will perhaps even enjoy it when another man kisses him. Sexual behaviors and the ensuing emotions between the two are rendered essential and presented as between two "fixed" roles: everything happens according to known, predefined formats. But their being gay is not enough to lead to a relationship-we already share in the understanding that Lam is a male prostitute who sells his body to men and that he refuses to have a relationship with another sex worker. In fact, it is queer knowledge that makes or breaks a gay relationship. The acknowledgement that "I'm gay [and] I can just look and I know who is gay, who is not gay" demonstrates a profound knowledge that only gay individuals share. More to the point, such an awareness is hardly innate or a matter of instinct. It comes as no surprise that Khôi, in this instance, does not know and must over time and through experience come to understand.

<14> As an older gay man who uses all he has at his disposal-his personal experiences, his charm and sexual attractiveness, his bravura and physical strength, and his financial status-to provoke and promote, to win over a younger man in his life, Lam is able to answer all the questions that Khôi asks. He is certain that he knows who Khôi is, what experiences Khôi goes through, and what Khôi needs. But their relationship breaks down when Khôi rejects Lam's way of living together. In order to live his life in a manner he deems appropriate, Khôi believes that he must leave behind the gay "paradise" where sex between men is easy and return to a space akin to what he understands as "his home." Put differently, he needs return to a space of heteronormativity as he prepares himself to embark upon another journey into knowing and another all-together different kind of knowledge, that of the university. The film concludes with a parting hope that some sense of a "gay" life awaits Khôi: from words superimposed onto the scene, we quite literally read about the diligence with which he prepares himself to stand the university examinations, knowing at this point in his journey that university, as a special space inhabited by young men, may promise its own gay paradise.

<15> I would like to conclude this essay with a single image from a scene at a multiplex located in a large shopping mall. Lam has taken Khôi for the first time to the cinema. While there, a middle-aged man accompanying a young girl spies Lam and recognizes him as one of his "boys." He follows Lam into the public toilet where he asks about Khôi. In fact, he offers a surprisingly large sum of money to watch the two "make love." However much Lam rejects the offer, we as members of the audience can expect no less than a sex scene between Lam and Khôi as we watch in the film-and all for less than 5 US dollars, the price of the ticket in Vietnam. As seen in Paradise, the cinema is the only public space-not the streets and alleyways-where male-on-male sex is for sale. It is also the only normative space where same-sex desire is openly negotiated and expressed, and eventually consumed.

Principle Cast and Crew

Director: Vũ Ngọc Đãng

Writer: Lương Mạnh Hải, Vũ Ngọc Đãng

Duck man (Hiếu Hiền)

Khôi (Hồ Vĩnh Khoa)

Lam (Lương Mạnh Hải)

Prostitute Hạnh (Phương Thanh)

Đông (Linh Sơn)

Acknowledgement: Unless otherwise noted, all images were acquired under a Creative Commons license.

Notes

[1] The title of this film in Vietnamese is Hot boy nổi loạn và câu chuyện về thằng Cười, cô gái điế m và con vịt (literally, Hot Boy's Rebellion, a story of a smiling guy, a prostitute and a duck." The film is usually referred to as "Hot boy nổi loạn." Premiering in Vietnam in October, 2011, it is considered the first gay film in Vietnamese cinema.

[2] "The medium shot, framed at the belt-all because of the gun, therefore the genitals. But only for the men" (Godard, Histoire(s) du Cinema 2007).

[3] From an interview with Hồ Vĩnh Khoa on a popular website, dated 7 November, 2010, before filming had begun: http://news.zing.vn.

[4] Tellingly, the marketing strategy for this work depended in no small part on generating rumors that the lead actor Hồ Vĩnh Khoa was likely gay. By the time the film premiered, he was being introduced as "a young gay man discovered by director Vũ Ngọc Đãng."

Works Cited

Godard, Jean-Luc. Histoire(s) du Cinema. 2007

Hot boy nổi loạn và câu chuyện về thằng Cười, cô gái điếm và con vịt. Dir. Vũ Ngọc Đãng. 2011. Film.

Return to Top»