Reconstruction 6.1 (Winter 2006)

Return to Contents»

Cold War Games and Postwar Art / Claudia Mesch

Abstract: During the Cold War both “superpowers” used games, particularly chess, in order to construct an ideology of complete conflict and irreconcilable division between East and West. This essay focuses on the broad cultural challenge to divisive Cold War zero-sum mentality issued by a number of artists—André Breton, Marcel Duchamp and Öyvind Fahlström, and Fluxus artists George Maciunas, George Brecht, Robert Watts, Takako Saito and Yoko Ono. These artists, in a second wave of game-focused art, returned to the concerns of surrealist art practice and to earlier cultural game theory. Even conceptual art production was impacted by the predetermined structure of games. As the global conflict dragged on into the 1980s, Deleuze and Guattari also touched upon chess in developing “nomad thought.”

<1> A large contingent of postwar artists and intellectuals engaged with notions of play and games during the Cold War era of the 1960s and '70s. The publications of the surrealists and their French and Czech disciples, Marcel Duchamp's elaborately staged "comeback" by means of his activities of the late '50s and 1960s, the artworks of members of Fluxus, and the "variable paintings" of the Brazilian/Scandinavian artist Öyvind Fahlström, all worked to contest what Dutch philosopher Johan Huizinga had earlier recognized as the barbarous and “puerile” censorship of play and games under fascism. During the Cold War, both "superpowers" used games -- particularly chess -- in order to construct the ideology of complete conflict and irreconcilable division between East and West. By the 1960s, these artists contested this appropriation of the notion of play as a realm for propaganda.

<2> A parallel intellectual development was elaborated in Huizinga's cultural theory of games of 1938, which was in part a response to the rise of fascism. In a development contemporaneous with Huizinga's study, mathematical game theory, a quantitative model of conflict, had been introduced as a new field by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern in Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944); it should be remembered that military conflict, and specifically the arms race, was the context and major impetus behind this mathematical achievement. In 1958 Roger Caillois, a cultural theorist who had been involved with the French surrealists, published his Man, Play and Games as a response to, and further development of, aspects of Huizinga's analysis. The preoccupation of postwar culture with the structure of games and with strategies of play can perhaps be attributed, and oftentimes directly linked, to the direction of intellectual and cultural history initiated by Huizinga. However, the thematic and structural foregrounding of the "play instinct" and of games across the work of many artists and artists groups after surrealism has not been adequately explored in art history.

<3> Art historians have traced the origin of the significance, indeed the centrality, of play and games to Western art of the modern era to the eighteenth century and to the period-style of the Rococo. It has further been argued that the "frivolous" Rococo artistic exploration of play and games is soundly rejected in the Enlightenment in favor of the "serious" delineation of aesthetics by philosophers such as Diderot, Kant, and Schiller. Jennifer Milam has, however, claimed that the "ludic impulse," as creative process and as "active engagement with the image," was central to Enlightenment thought and to the formulation of modern visual experience [1]. Further consideration of the role of the game within visual modernism complicates the widely-held high-modernist view of the interaction of the "autonomous" modern with the popular, and establishes new points of contact and dispute between art and an increasingly game-based visual pop culture. Where most art historical examinations of the dynamics between modernism and popular culture have focused on the circulation of the imagery of advertising, late twentieth-century artists consistently turned to the game as structure or subject for their art.

Cultural Theory of Games

<4> The burst of cultural theory centered on games in the twentieth century can be said to begin with Dutch philosopher Johan Huizinga, and with his first lecture on the play element in culture in an address at Leyden in 1933, followed by lectures in Zurich, Vienna and London; his Homo Ludens, a Study of the Play-Element in Culture was published in Leiden in 1938. Huizinga's resounding condemnation of the cultural and intellectual perversions of Nazism is also a modern-day tale of cultural decline which both recalls the pessimistic pronouncements of Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West (1918-22) and precedes those of the Frankfurt School . Huizinga mourned the dissipation of play in the twentieth century, and with it a code of ethics and a corresponding quality of human decency. He identified the "play impulse" as an inherent characteristic of human society and as an underlying structure of culture more generally, not only in the creative act of poetry and art, but also in the waging of war in accordance with a "code of honor" and "the law of nations." Beginning with Plato's identification of human play activity as a kind of holiness, Huizinga sees play as central to ritual and inseparable from it; he discusses the use of masks in archaic cultures in marking the realm of "sacred play," a quality he claims has never wholly disappeared from social life and can still be manifested as "sheer play" (26). He charts the epistemological function of play within world history. He then identifies five core qualities of human play throughout world history: 1). that it is voluntary in nature; 2). it is separate from "real life"; 3). it has a beginning and end and must be repeatable; 4). it creates order in shifting between the states of tension and resolution of conflict; 5). all human play has rules. Huizinga also traces the end of play activity in the sphere of the visual arts, where he dismisses contemporary art as overly esoteric and too concerned with the proliferation of "isms" -- the "game" of a specialized critical discourse around modern art as it hurls itself toward the ever-more "new". In a passage that recalls the contemporaneous analyses of Walter Benjamin but lacks both his political radicalism and familiarity with the avant-garde, Huizinga notes how changes brought about in art by photographic reproduction work against the development of a "play-element" in art: art becomes at once too self-conscious and too connected to the market to retain its "eternal child-like innocence" (202).

<5> Huizinga concludes with a powerful critique of the "friend/foe principle" outlined in the political philosophy of Carl Schmitt, which, Huizinga argues, destroys the ethical workings or "fair play" aspect of international law [2]. Huizinga explains how Schmitt's theory recasts the relation between states:

The theory refuses to regard the enemy even as a rival or adversary. He is merely in your way and thus is to be made away with. If ever anything in history has corresponded to this gross over-simplification of the idea of enmity, which reduces it to an almost mechanical relationship, it is precisely that primitive antagonism between phratries, clans or tribes where...the play-element was hypertrophied and distorted. Civilization is supposed to have carried us beyond this stage. I know of no sadder or deeper fall from human reason than Schmitt's barbarous and pathetic delusion about the friend-foe principle. His inhuman cerebrations do not even hold water as a piece of formal logic. For it is not war that is serious, but peace....Schmitt's brand of "seriousness" merely takes us back to the savage level. (209)

Thus, Huizinga writes, Schmitt provides the intellectual foundation for the adolescent "puerilism" of fascism and its culture in 1938, a perverse "boy scoutism" without playfulness and thinking itself beyond competitiveness, a world of yelled greetings, the wearing of badges and "political haberdashery," of "collective voodoo," crude sensationalism, pleasure in mass meetings and parades -- simply, the "bastardization of culture" (205-6). However he finally trusts that moral consciousness (a "drop of pity") will return with the awareness that human action may be "licit as play": "But if we have to decide whether an action to which our will impels us is a serious duty or is licit as play, our moral conscience will at once provide the touchstone."(213). Huizinga trusts that the play-instinct will reject thinking such as Schmitt's and compel a reentry into the sphere of ethics and civilization.

<6> Perhaps due to his aversion to the economic totalizations of Marxism, Huizinga did not theorize the place of games within the capitalist economy. Caillois' Man, Play and Games (1958) pointed critically to Huizinga's decontextualized and teleological narrative of play-as-drive that established it as an enduring human quality throughout all of world history. Caillois considers the significance of games within contemporary capitalism and also the element of gambling. Well before Foucault, Caillois advances a nuanced theory of power that is more optimistically based upon the rise of competition and its dialectic with alea, or the chance advantages of a privileged birth; Caillois raises the possibility that power in modernity flows not unidirectionally but is circulated and contested in democratic society.

<7> To formulate a less abstracted study of play culture, Caillois developed a taxonomy of existing games, which he delineated on two axes: 1). ludus, games that are subordinated to the disciplining framework of rules, and 2). paidia, games that consist of spontaneous and even tumultuous activity. On the other axis Caillois places the categories of: 1). Agôn, games of competition; 2). Alea, games of chance; and 3). Mimicry, games of simulation and play behavior, such as the playing of a role in theater, in children's games, or by means of the process of identification with another within the act of spectatorship, as in, for example, the cult-like worship of film stars or athletes; 4). Ilinx, or games that pursue vertigo, disorder and physical disorientation, as is offered by amusement park rides like the rollercoaster.

<8> Caillois's taxonomy claims a wider berth for games within human society, and in the animal kingdom, than does Huizinga. He does not ascribe rules or an ordering function to all games, as he understands that paidia- and ilinx-type games may not operate on rules or may even strive toward disorder; in fact, he concludes that games either have to do with rules or they have to do with "make-believe", with "acting as if". Caillois tracks the development of civilization, or democracy, in the shift from paidia to ludus, across numerous world cultures, and in the "struggle against the prestige associated with simulation and vertigo" in democratic societies (100). He understands the use of masks in ancient society along these lines;he describes how the mask is used as a symbol of superiority, furthering the inequity of power by instilling terror in political inferiors in the "reign of mimicry and ilinx" (105-7). When, for example, the Greeks, through the use of mathematics, began to understand the universe as ordered, agôn and alea also began to structure social life. Regulated competitions thus take on significance, relating to the founding of numerous games -- Olympic, Pythian, the Aztec game of pelota, and Chinese archery contests. Further, competitive examinations come to determine a bureaucratic elite. According to Caillois, social power comes to be achieved rather than ascribed; it becomes dominated by the shift between merit and inheritance, or by competition and chance. Soon regulated competition becomes dominant, even between social classes.

<9> Caillois reads the return of alea in the vague promise of a miracle, the "sudden success" of winning the lottery or the grand prize on a game show for those who realistically realize that they cannot achieve due to personal merit. This statistically miniscule possibility of a quick fortune proved to be a useful source of funds for the capitalist state, and for other for-profit gambling corporations of the mass media that mushroomed in the Cold War era. The rise of alea becomes an engine for the "disguised lotteries" that sprout on TV game shows and appear to reward achievement, but are a "compensation for the lack of opportunity for free competition" (118 ff) [3]. Caillois claims that the game had always had the function of clearing a field or of establishing conditions of pure equality. The game can therefore be deployed to create the illusion of that condition as well; within advanced capitalism, rules can be appropriated to offer up the "as if" of "make-believe".

Games and Modern Art

Surrealist Games and Game Theory

<10> It is ironic that Huizinga seems to have been completely ignorant of the activities of the avant-garde and of the surrealists within the realm of visual art. Caillois' expanded theory of games in modern society is possibly attributable to his involvement with the surrealists and to their refusal and rethinking of hardened polarities such as seriousness/nonseriousness, or work/leisure. In the 1950s, André Breton recognized that the surrealists had, by means of the games they devised, reconfigured the process of art-making in toto and even the workings of knowledge and language. Huizinga prompted André Breton, in the interviews that make up his memoirs ( Entretiens, 1952) and in a number of essays in Médium (beginning in 1953), to reclassify almost the entirety of surrealist practice as the playing of games [4]. Breton claimed that while the group (that is, he) first understood games merely as a kind of social glue and collective entertainment, and in embarrassment concealed their games as "experimental" activities, he only later realized the epistemological "discoveries " it could generate. In his catalogued list of surrealist games, Breton did not separate the automatist procedures or games of dessin, or of the visual arts, from those involving language: the exquisite corpse is described as "written or drawn"; the "recipes" of the visual arts, listed as "collage, frottage, fumage, coulage, spontaneous decalcomania, candle-drawings, etc.," allowed, so Breton remarks, "greater satisfaction of the pleasure principle" in that such games could put the possibility of art-making in anyone's hands.(Breton, cited and trans. in Gooding, 137-8).

<11> In contrast Philippe Audouin, in his analysis of surrealist games, establishes another category, games of objects, under which he groups the "Recherches Expérimentales," (Experimental Research), the "Cadavers Exquis dessinés" (Drawn Exquisite Corpse), the "Jeu de Marseille" (Marseilles Game) and the "Cartes d'Analogie" (Analogy Cards). According to Breton, surrealist language games (as Audouin would later classify them) such as "Définitions" (Definitions, first published 1928), the "Jeu des Conditionnels (Si...Quand...)" (Game of Conditionals -- if...when..., 1929), "le Cadaver Exquis" ("Exquisite corpse," 1927), and "l'Un dans l'Autre" ("One into another," 1954), and the games of options or opinions (Audouin), such as the "Notation Scolaire - 20 to + 20" (Scholarly notation, 1921), and "Ouvrez-vous?" (or the Visitor, 1953), yielded similar pluralistic possibilities as predetermined game-frameworks within the manipulation of language [5]. Breton's 1954 comments on Huizinga and surrealist games appeared with his description of "l'Un dans l'Autre", developed with Benjamin Péret -- a year earlier he had published "Ouvrez-vous?", a new collective game [6].

<12> Of the surrealist games which Audouin determined to be concerned with the visual, the "Recherches Expérimentales", the "Cadavres exquis dessinés", the "Jeu de Marseille" (1940-41) and the "Cartes d'Analogie" (1959), often had to do with the construction or circulation of cards, either playing cards of the "Jeu de Marseille"or the fictional and collectively fashioned "identification papers" of the "Cartes d'Analogie" (Game of Analogy Cards). Both of these forms engaged with the immediate wartime experience of the surrealist circle, with the state of physical transience of travel, with their forced relocation and exile to New York and other locations, with the continued demand to present identification papers while traveling in occupied France, and perhaps also with a sense of being pitched into the realm of pure alea. The "Cadavres exquis", a procedure devised so that a collective could by means of automatism assemble or "compose" a singular work and avoid the conscious control of any individual author, opened, as Breton saw it, a "strange possibility of thought, which is that of its pooling" (Breton, Second manifesto). However in including as its pool of players only practicing visual artists, the game (or Breton) did presuppose the seriousness of artistic training as its basis. Surrealist games can then be best understood as tools toward automatism, as strategies that attempt to pool a process of collective thought unmediated by the individual ego, or, to short-circuit the conscious workings of the individual mind as it works its way through and applies the rules of the game to the actions at hand. Sometimes, as in Robert Desnos' plunges into hypnotic states, games of ilinx (physical and mental disorientation) are instead pursued. In surrealism the ends of agôn, that is, the regulated and antagonistic relation between powers and drive to win, are repositioned such that the id, either individual or collective, might, with the proper surrealist preparation, discipline and perseverance, be summoned up as a reluctant opponent and finally be forced to reveal itself in language and in image.

<13> The "Jeu de Marseille " is most interesting in that it is the collective project/game undertaken immediately before many of the contributing artists began their exile from fascist-controlled France [7]. Incorporating a woodcut by Alfred Jarry and drawings by the above artists, this playing card deck included new court cards -- genius (in lieu of king), siren (queen) and magus (jack) -- and new suits: flame (love), star (dream), wheel (revolution) and lock (knowledge) (Gooding 124-5, 160; Audouin 485) [8]. Recognized in this project is the quality of card-playing as a means of passing the time, and as a characteristic of waiting, and the projection of skill and ability into an uncertain, changing situation. Card-playing is a game that combines both alea and agôn; in certain card games agôn, in terms of the experience and strategy of the card player, can determine the winning hand.(Caillois 18). The surrealist card game, undertaken in transit and a time of great uncertainty, works to foreground human will in the situation where fate, chance, or the specter of totalitarianism, seems to have overtaken it.

Duchamp and Chess

<14> Certainly the slippery interchange between chance on the one hand and merit or human will and ability on the other was also well known to Marcel Duchamp. Perhaps more so than any other artist of the twentieth century, Duchamp concerned himself with this divide and with the structure and process of agôn, as it delimits human action and as it is personified in the game of chess. He understood the ludic impulse and the agonistic structure of the universe, within the Machine Age, to take place on the plane of eros, and within the tensions, resolutions, and displacements of sexual play. In his art Duchamp systematically introduced the element of gender and tied the confrontations and negotiations of eros to the field of agôn. The surrealists -- Giacometti, Ernst, Man Ray -- also made reference to chess, but the game did not buttress the entirety of their artistic production the way it did Duchamp's.

<15> Chess, one of the oldest and most rigidly competitive of games of agôn, is, as Caillois understood it, an ultimate contest of agôn, in requiring players to compete as rigorously and intensely as they can with the goal of winning (15). Winning is required of a player in order to achieve ranked status in chess, which Duchamp pursued aggressively in France during the 1920s. "Wouldn't you rather win?" Duchamp is said to have dryly queried Walter Hopps while they deliberated the roulette tables at the Golden Nugget Casino in Las Vegas ; as chance would have it (at least according Hopps), Duchamp's instructions at the tables resulted in a considerable win [9]. Can Duchamp be understood as the most competitive artist -- that is, one who was most concerned with winning -- in the twentieth century? This reading goes against a prevalent postmodernist understanding of the game or gaming as the possibility of endless play without result or concern for an outcome, as it is advanced in the writing of Jean-François Lyotard or by Jacques Derrida, and as this has been applied to Duchamp [10]. According to Arturo Schwarz, Duchamp himself insisted he was far more interested in investigating how the language of chess could realize the beautiful than in outplaying an opponent; yet this was surely not Duchamp's view as he played competitively in the 1920s [11]. But one can also make the claim that the recasting of all human interaction, including heterosexual sexuality, into the guise of agôn, and thereby creating situations that could be mastered and possibly won -- a process of conversion which one can read throughout his entire oeuvre, even in his final epic work, the "Etant donnés" -- seems to have interested Duchamp most.

<16> Duchamp's love of chess, the game most removed from the workings of chance, is apparent. One can trace one origin of Duchamp's concern with chess and agôn in the iconography he developed early in his oeuvre, while he worked within the medium of painting: in his Cézanne-esque paintings of his brothers at the chessboard of 1910 and 1911, and in the paintings of the following year that removed these figures and focused exclusively on the movement of the chess piece in play: "Le Roi et la Reine Traversés par des Nus Vites" and "Le Roi et la Reine Entourés de Nus Vites." Duchamp famously declared in 1923, a point in time which coincided with the "completion" of his earliest epic work, the "Large Glass," that he had stopped being an artist and would in the future only concern himself with chess [12].

<17> Indeed, in the late teens and 1920s he played competitively in Argentina and then as a ranked player in France, and produced chess pieces and other chess paraphernalia [13]. For a time thereafter Duchamp worked directly on the problem of reconfiguring or transforming alea (roulette) into pure agôn (chess). While the intellectual challenge of the task attracted Duchamp to the project -- it is quite impossible, which he later recognized -- he was clearly also motivated to "break the bank", that is, to garner a huge profit by means of gambling, and, further, to reconfigure the functioning of the capitalist economy, if his model were to be a success [14]. He coauthored a treatise, "L'Opposition et les Cases Conjugées sont Réconciliées Par M. Duchamp & V. Halberstadt" ("Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled by M. Duchamp and V. Halberstadt," 1932) on an obscure chess end-game problem; and produced, for Julien Levy's "Imagery of Chess" exhibition of December 1944, a "pocket chess" assemblage, manufactured as a multiple in 1966 [15].

<18> It was in the '60s, in and around his Pasadena retrospective exhibition of 1963, that Duchamp presented himself as a chess player within the realm of art, a reversal of his earlier insistence that his activities in these two domains were wholly separate or mutually exclusive. One asks why Duchamp seized upon this radical reversal shortly before his death [16]. In addition to the reissue of many of his readymades and the above-mentioned assemblage as multiples, and the permission to produce duplicates or "replicas" of many major works for the 1963 exhibition [17], Duchamp posed while playing chess during a number of highly-publicized appearances both during and after the 1963 exhibition. Many of these appearances are captured in Julian Wasser's series of photographs of Duchamp, as well as in the film "Jeu d'echecs avec Marcel Duchamp" by Jean-Marie Drot, all of which were completed during and shortly after the Pasadena exhibition.

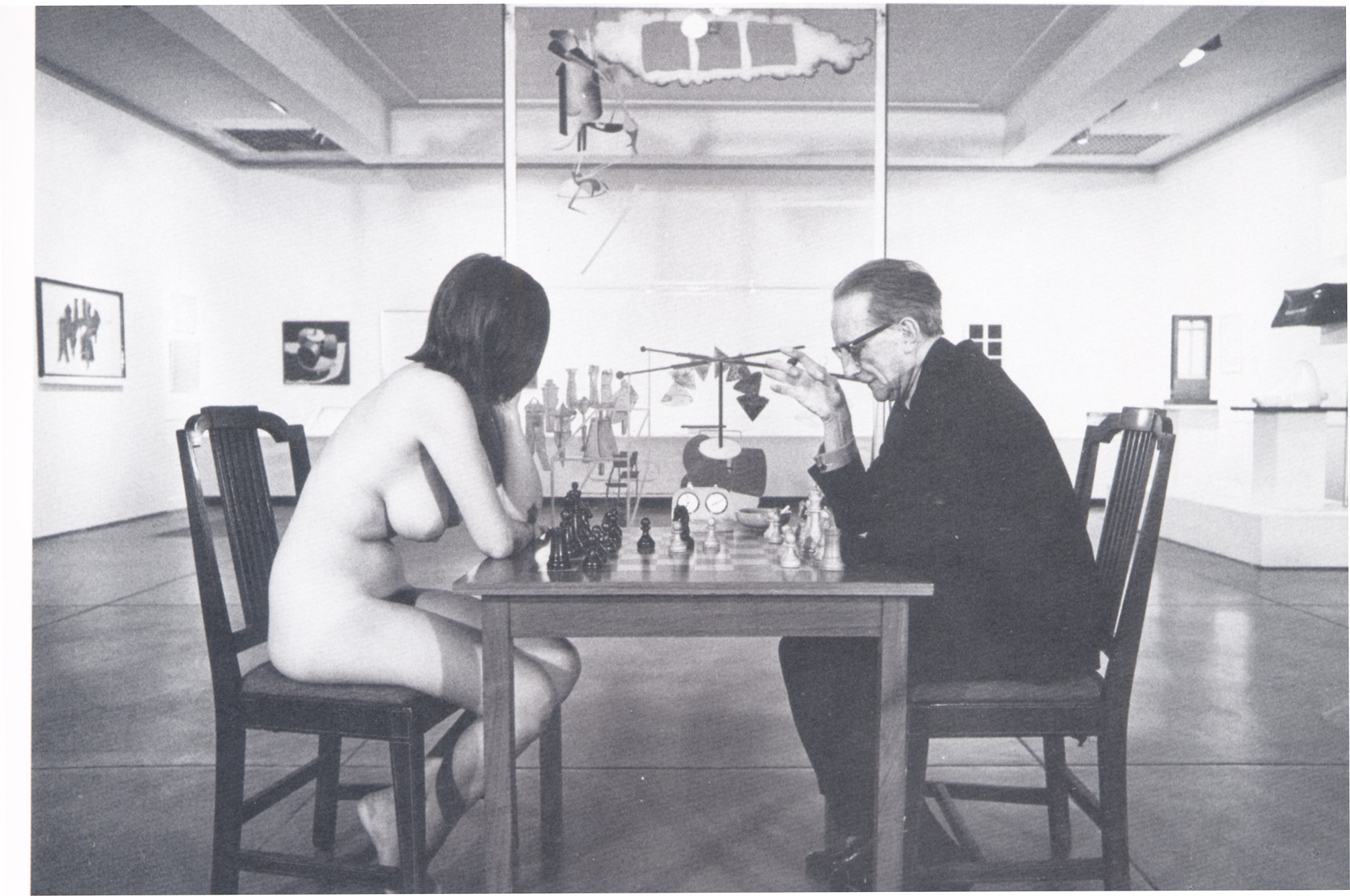

<19> The most widely disseminated image by Wasser of the chess match between Duchamp and the nude Eve Babitz, a female friend of Hopp's (Fig. 1), was shot on October 18, 1963 in the Pasadena gallery which featured the "Large Glass" surrounded by the readymade replicas and related works in the Duchamp exhibition [18]. Wasser and Duchamp staged this game before the "Large Glass"in order to emphasize its composition or even in a sense to perform it; during the opening Wasser had photographed Walter Hopps, the curator of the exhibition, and Duchamp playing in the galleries. For the exhibition Hopps had placed the early chess-related drawings and paintings in the second gallery, which also featured chess paraphernalia (presumably the chess table, board and clocks). Tashjian claims that the Babitz/Duchamp match was a chance event whose genesis cannot be traced to any one person, neither to Wasser nor to Hopps, but was an idea that Duchamp agreed to. It seems a highly deliberate, coordinated and meaningful decision to have moved the playing table into the next gallery and to have staged there, for the camera and before the "Large Glass," a chess game between Duchamp and a female nude named "Eve," the biblical Ur-bride. Tashjian suggests that several aspects of this event are purely "serendipitous." Duchamp had already related the biblical female nude to the movement of chess pieces across the board: with a nude "Eve" depicted within his earlier painting " Paradise " (1910-11), which featured a nude model posing as Eve, a painting which further became the verso of "King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes." The Wasser image also recalls Duchamp's theatrical appearance as the nude Adam to Brogna Perlmutter's Eve in Picabia's "CinéSketch" of 1924, which was recorded in a famous photographic image; the image is also reminiscent of a 1936 photograph of Duchamp at the chessboard in front of "Nude Descending a Staircase"; and the image interacts with the complex iconography of the "Large Glass" itself, its segregation into female and male domains and its direct references to chess in, for example, the "Nine Malic Moulds" of the lower panel [19]. While Duchamp may not have arranged the event himself (as Babitz's account suggests), it is likely that given the resonances of the image there, he would have suggested the game should be staged before the "Large Glass."

Fig. 1, Julian Wasser, Marcel Duchamp and Eve Babitz, 1963.

<20> However both Babitz's image and her own recollection of the event have effectively been erased from art history. Tashjian notes that her account of the event was dismissed by Wasser and that her essay, "Me and Marcel," remained unpublished. In Wasser's image, Babitz's hair has fallen over her face in her absorption in the game, erasing her as an individual adversary or player from the scene; in contrast the camera captures Duchamp's absorbed gaze and his gesture, as though he is explaining or gesticulating a recent move. Are we really to understand that this erasure of a chess player and her transformation into a faceless female body is also "serendipitous"? Duchamp after all won the game (Schwarz 88) [20]. Wasser's arresting image of an urbane, elegant, even youthful Duchamp engaged in chess with a voluptuous younger gaming partner reconnects to Duchamp's investigation of the eros of agôn (or the agôn of eros) in the "Large Glass" by displacing the onanism of the grinders of the "Glass" onto the movements of the pieces in the game between himself and Eve. However, she is all but erased as a thinking player, as an opponent and subject, in the process. This final image must not have been selected from the proofs by Duchamp, since it conforms to a long lineage of female nudes retinally transformed into objects by male artists -- Duchamp would never have been so crude or conventional [21]. Yet the concept behind this staging of a chess match is a sound, that is, that chess offers the realm of agôn, where adversaries confront each other under ideal conditions. In chess therefore a condition of equality is assumed between players regardless of gender; equality must be taken as a point of departure. The photograph negates this essential aspect of agôn, which had previously always concerned Duchamp.

<21> Duchamp was also photographed playing with Hopps in the museum's galleries with people crowded around them; five years later, in an auditorium at Ryerson Polytechnic in Toronto with his wife Teeny at his side (fully clothed), Duchamp was again photographed at play in a chess game in two parts against John Cage (he lost one, but Teeny won the second). The game was also titled " Reunion " by Cage, a musical composition, and the chessboard was connected to both light and sound sensors that issued sounds corresponding to the moves of each player (Schwarz 88). In returning to the foundation of his art in chess late in his career, Duchamp configured himself publicly as a challenger or opponent to the younger avant-garde of the '60s such as Cage. Duchamp's phrase "Tous les joueurs d'échecs sont des artistes," further reminds of the realm of precision and beauty that agôn should and can occupy and of the importance of games as art, where the agonistic impulse of eros can be located as a creating force, and not one appropriated by Cold War propagandistic apparatus in order to foreground, metaphorically, the nationalistic militarism of "mutually assured destruction," as the saying went [22].

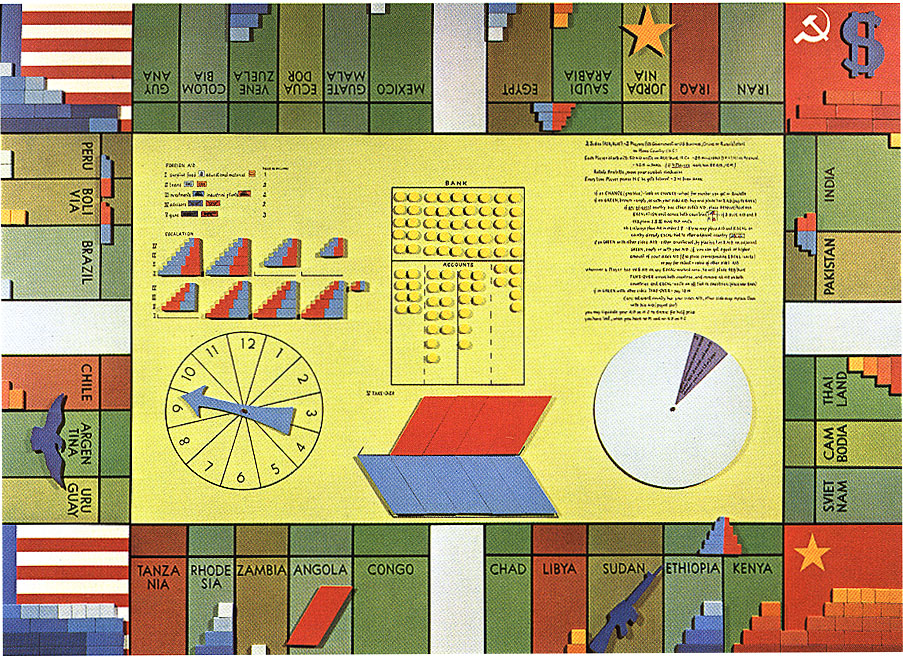

Oyvind Fahlström: Painting and Cold War Metaphors

<22> The willful desire to "manipulate the world" through game-like structures -- no less than the medium of painting -- is discernable in the remarkable "variable paintings" produced by Öyvind Fahlström during the 1960s and '70s. As in Duchamp's work, Fahlström used the game structure as a foundation for his art and as a filter for the perception and rejection of Cold War ideology. Games were finally the cultural field where Fahlström could assert the agency of the viewing subject. Fahlström understood that his paintings were "creating and relating models of the world; not symbols -- anyone may put in whatever he finds -- only he sees (some of) the relations: what is like, unlike, repeated, juxtaposed, etc., etc" (Fahlström "Notes" 32). Fahlström, who is said to have studied surrealist art carefully, was clearly aware of the powerful implications Breton had identified with the use of game elements and structures. He was also fascinated with the dualistic property of games that Caillois had noted, that is, that both agôn and alea are always to be found together, or that chance can never be completely ruled out of even the strictest games: Caillois gives the famous example of the question of whether the opening move in a chess match gives an advantage to that player (Caillois 202 note 98). The board games of Monopoly and Risk, which remained popular throughout this period, influenced Fahlström's reconfiguration of painting, which he achieved by means of ferrite-magnets attached to individual elements which were in turn placed on a wall or a larger flat surface where they could be manipulated. In variable painting works such as "Sitting...Six months later" (1962), "Dr. Schweizer's Last Mission" (realized in several phases: "Phase I," 1964-66, Venice Biennale; "Phase 3,"1973, Moderna Museet, Stockholm; "Phase 7," 1981, Westkunst Cologne), "The Cold War" and "World Politics Monopoly" (Fig. 2, 1970) the rules of advanced capitalism and of Cold War division are presented to the viewer to be manipulated and played upon. Therefore the variable paintings present diagrams or metaphors, albeit very simplified, of the complex relations that contribute to the reality of Cold War culture.

Fig. 2, Öyvind Fahlström, World Politics Monopoly (1970).

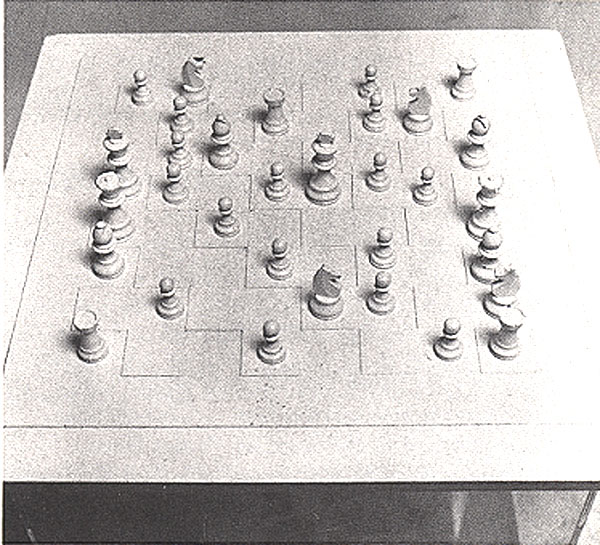

<23> Fahlström's magnetized elements allowed for the free manipulation of forms by the viewer, enabling the "bisociation" of elements, whereby their connections to each other or to "factual images of erotic or political character" could be realized (Fahlström "Take" 63). The ephemeral compositions of Fahlström's variable paintings explicitly rejected what he called the compositional strategy of "neodadaistic unrelationships," where compositional elements are "cut off and isolated" (Fahlström "Notes" 32). The magnet became a building block for his "picture machines", the connective tissue that would allow for variable movement and bisociation of elements. This would render painting indefinitely transformable, and would further postpone finality or completion of the painting itself: "the transformable paintings [which] never are one same picture..." (Fahlström "Notes" 32-34). These works were game-like on several counts: Fahlström states that the game is "a simple, fundamental outlook on life" (Fahlström "Games" 58), a notion which he takes not from mathematical game theory but from John Cage's notion of composition and from psychology. Games are, in Fahlström's view, characterized by rules. Fahlström identified the rules of his own art as the immutable aspect of the magnetic objects in terms of their "appearance, construction and substance". However, the central tension of the "fundamental principle" of the game-paintings was the paradox between the viewer/player's freedom to manipulate and arrange the objects and the limits of their resistance to this manipulation, their predetermined inflexibility or immutability as flat, figurative images determined by the artist. Freedom of choice opposes the rigidity of external appearance to "the other rules -- like our conventions and agreements: the border between the Congo and Angola, the numbers in the telephone book, the buttoning of jackets" (Fahlström "Games" 58). The variable paintings realize a model of social and political reality where the possibilities of play and manipulation oppose the unalterable mechanisms of ludus within capitalist society. Fahlström's game paintings insist on a space for human agency within complex and militaristic international relations. He insisted that his variable paintings could only be successfully realized as mass-produced and distributed multiples, "so that anyone interested can have a picture machine in his home and 'manipulate the world' according to either his or my choices" (Fahlström "Manipulating" 45).

Games in Conceptual Art and Fluxus

<24> The inherent qualities of games of agôn (competition) and alea (chance) were also taken up, but developed in another direction, by conceptual artists of the 1960s. It could be argued that the game, with its characteristic quality of actions of infinite repeatability based upon "precise, arbitrary unexceptionable rules that must be accepted as such and that govern(s) [the] correct playing" (Caillois 5) [23], can constitute what Sol Lewitt identified as a "plan". In Lewitt's description of the artistic process of conceptual art, the plan mitigates subjective taste and fancy: "The plan would design the work....the artist would select the basic form and rules that would govern the solution of the problem. After that fewer decisions made in the course of completing the work, the better. This eliminates the arbitrary, the capricious, and the subjective as much as possible. That is the reason for using this method" (Lewitt 824). While Lewitt clearly did not take up the game as such in his art, its quality as a predetermined process similarly works against subjectivity. Indeed, this interest in the manipulation of a predetermined structure -- or better, an interest in a predetermined structure that can run its course with minimal "creative" interference -- is shared by the art practices of both Fluxus and conceptual art [24].

<25> A second game-like aspect was also implicitly pursued by much conceptual art of the '60s and '70s: the refusal of a process (of production) culminating in the manufacture of new goods. Caillois writes that this quality was central to all games and play, even in cases where games are played for profit: "A characteristic of play, in fact, is that it creates no wealth or goods, thus differing from work or art. At the end of the game, all can and must start over again at the same point....Play is an occasion of pure waste: waste of time, energy, ingenuity, skill and often of money for the purchase of gambling equipment or eventually to pay for the establishment" (Caillois 5-6). Games, even as they are played within the established functioning of the capitalist economy, stand aside of economic exchange and its telos of the generation of durable goods and surplus value. Games therefore establish a critical distance from that same economy, which is also a goal of the best critical art of the postwar period. Though direct evidence of Fluxus' and conceptual artists' engagement with cultural theories of games as they were advanced in these years by Huizinga, Breton, and Caillois, among others, is still to be established [25], the common critical-theoretical postures and strategies of games and of art developed in the Cold War era, along with the oftentimes explicit appropriation of game forms and formats by artists, is clearly significant [26].

<26> Fluxus artists, particularly impresario George Maciunas and Robert Watts in their unrealized commercial venture, The Greene Street Precinct, Inc., gave serious thought to the place of games in art and to reconfiguring the conventional sites of art exhibition [27]. Fluxus always cultivated the qualities of play, which Maciunas understood as being connected to the mass-culture phenomena of amusement and entertainment within art. These qualities were not permitted within high modernist aesthetic experience as it had been codified in the writings of Clement Greenberg [28]. It is logical that games as a major component of mass culture entertainment would have interested Fluxus as a kind of readymade amusement that could be appropriated and redeployed as Flux-games. Already in a number of manifestoes and manifesto-like letters he completed in the early 1960s, Maciunas agitated for nonprofessionalism of the producers of art, and therefore for a leveling of the roles of artist and audience. He condemned formalist art as "a useless piece of merchandise whose only purpose is to be bought to provide the artist with an income" (Maciunas "Letter" 82-4). Fluxus was instead to be "in the spirit of the collective," anti-individualistic, aiming at the elimination of an institutionalized market for bourgeois art, which Maciunas condemned as the "world of Europanism." Part of the Fluxus idea of the evaporation of art was to be realized in an accompanying expansion of the role of art in society, where art "must be unlimited, obtainable by all and produced by all." According to Maciunas the content of this universally produced art must also change and become "substitute art-amusement," which was to be simple and "concerned with insignificances" like vaudeville (Maciunas "Fluxamusement" 14). Therefore, no single producer of art can claim to be significant. Maciunas also insisted that artists "demonstrate [their] own disposability" in dismantling of individual subjective expression, a strategy which, as I explained above, greatly influenced LeWitt's notion of conceptual art, though LeWitt would in contrast remain uninterested in apparatus and mechanisms of mass culture such as games.

<27> Maciunas developed his notion of "Fluxamusement" in his "Fluxmanifesto on Fluxamusement," of 1965, which perhaps drew from Henry Flynt's 1963 lecture, "From Culture to Veramusement." In his manifesto, Maciunas outlines a plan for forms of "fluxamusement" or "substitute art-amusement." This relates mass-culture amusement to art, a topic that had also concerned Bertolt Brecht in his theorization of his "epic theater" in the 1920s and '30s. Brecht understood that his epic theater must also appeal to the audience's pleasure, amusement, or "fun," an aspect so carefully provided for the viewer in such mass entertainment forms as the circus, or, as Maciunas later realized, in the playing of games. Brecht understood that this kind of entertainment appeal was necessary to compete for the mass public's attention, and to provide a measure of "irrationality" and "lack of seriousness" which might bring the public to the realization of social and political injustice. For Brecht, amusement was key to the political efficacy of epic theater, which could illuminate the material conditions of the underclass [29]. While Brecht's explicit politicization of "amusement" is missing from Maciunas' writing, he provides the beginnings of a theory of the critical potential of games within mass culture society, which Maciunas perhaps strove for but could not elaborate.

<28> Even the physicality of certain aspects of Fluxus performance was based on the recovery of the "gag," the fleeting aspect of physical humor that was also invoked in physical acts of destruction, which Fluxus sometimes staged in its performances. It may be the case that Fluxus pieces such as Higgins' "Danger Music No. 2" (1962) or Maciunas' "Piano Piece No. 13 for Nam June Paik" (1964) recall American slapstick comedy in the manner of the Marx Brothers, a tradition from vaudeville -- a kind of popular theater that Maciunas particularly valued -- as much as it does the direction of postwar concrete art [30]. Fluxus incorporated blatant physical silliness or play as a unifying element for their performance activities and for many of their manufactured multiple-objects and games. Not only were Fluxus events banal, for Maciunas, they also had to be silly amusements, transient and lacking seriousness.

<29> Fluxus performance was generally not participatory as it was almost exclusively performed by Fluxus artists and not by audience members, for example, at its usual venues of art galleries and concert halls. The participatory element, where it is to be found at all in Fluxus, materializes in Maciunas' Fluxus multiples, the "Fluxkits" and "Yearboxes," and particularly in Fluxus games and fluxchess. These objects directly address and initiate the viewer's physical confrontation and tactile participation in the process of play and absurdity that Fluxus performance only staged before the viewer's eyes; Maciunas' distribution of cheap objects in kits was central to the development of the multiple as a participatory medium after 1960. The viewer's participation in Fluxus, then, is rooted in a repetition of the diversionary pleasures of the consumption of the products of mass culture.

<30> Fluxus did not enact an explicit Brechtian negation of the life conditions of the underclass: Fluxus established no explicit connection either to radical politics or to the student movement of the '60s, unlike other artists such as Joseph Beuys or Yoko Ono [31]. Maciunas only communicated a vaguely populist aesthetics to be achieved through the embrace of commercial art and amusement forms and in art's eventual disappearance into the forms of cheap commercialism. But the cheap, low-brow pleasures of fluxamusements and fluxgames function as negations of an elitist and anti-ludic visual modernism, following Greenberg's postwar definition of the term.

Fluxgames and Fluxchess

<31> In Fluxus projects, Watts, George Brecht, Yoko Ono and Takako Saito reengaged with chess or with the puzzle in various multiples: Fluxchess kits by Ono and Saito and a manufactured series of puzzles and playing cards by Brecht and Watts could be purchased by mail order from the Fluxshop. Playing cards were designed by both George Brecht and Robert Watts. In 1959 Brecht had shown his work Solitare at the Reuben Gallery's Towards Events exhibition in New York, which was, according to Brecht, a new card game he had adapted from the rules of Solitaire. Brecht's notion of the event, a central unit of his performance practice, was then clearly connected, if not developed from, the rules or instructions that comprise games. Everyday and banal, the single concrete event could be, in Brecht's Fluxus performances, the simple act of exiting a room (Exit) or of counting in unison in different ways. The Brecht event, as it was communicated in his short written scores or instructions, then presents rules of a particular game that the viewer subsequently agrees to engage in.

<32> Brecht's playing cards were to be manufactured and distributed by Maciunas under the "Games & Puzzles" label as a Fluxus edition. Robert Watts had designed a program cover for the June 1964 Fluxorchestra concert at Carnegie Hall in New York, which featured face card-like designs so that the program could be held by audience members like a hand of cards. Watts' "instruction drawing" to accompany the playing card deck remains unexplained; the drawing features a recto and verso view of a gender-neutral human body where various body parts are numbered from 1 to 56. Whether these body parts were to be featured on various cards or whether Watts conceived of an elaborate strip-poker scenario for card players is unclear. Watts completed a prototype deck of Playing Cards for Fluxus, but these were never manufactured due to the cost involved [32].

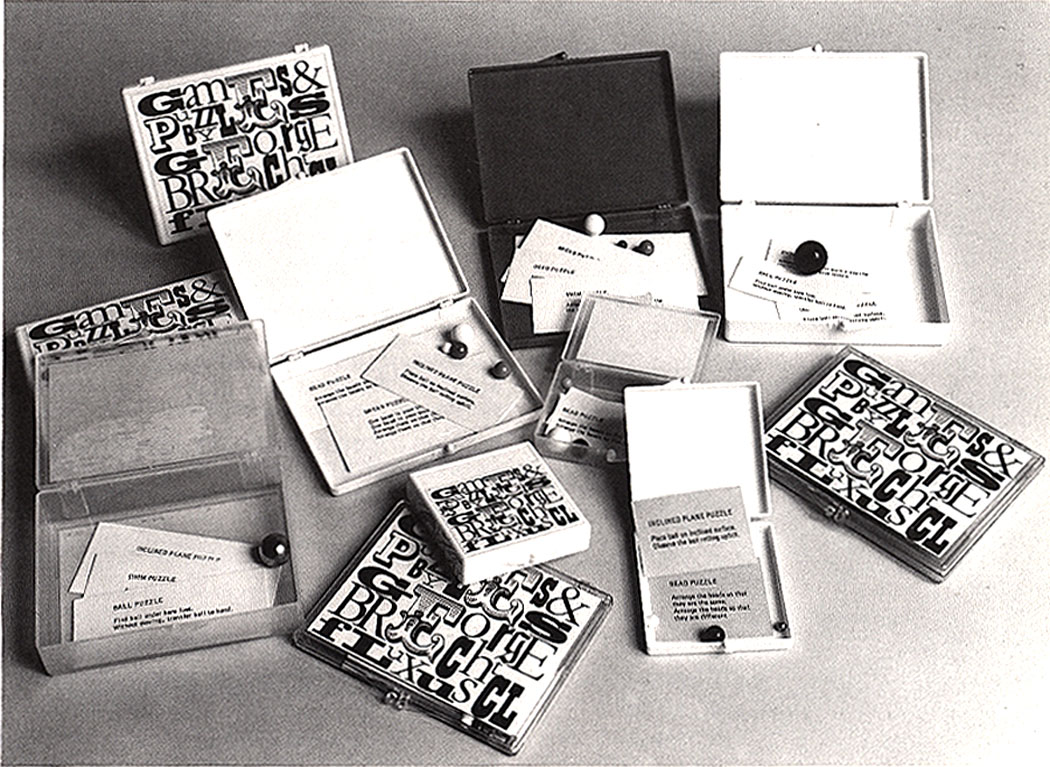

<33> Contrary to the contemporaneous art-games of Duchamp and Fahlström, Fluxus artists displayed an interest in fashioning the art-game as a complex intersubjective situation or interaction that went beyond -- or rejected -- the zero-sum scenario of most games of agôn and alea and its conclusions, that is, where players have diametrically opposed interests and either win or lose. Fluxus art-games often dismantle the notion of competition altogether, a central aspect of agôn, in making competition more difficult or even impossible in its conventional sense, which usually has to do with a player's skill in assessing visual information. In rendering competition itself nonsensical, Fluxus artists reintroduced the element of paidia, the category of spontaneous play and fantasy Caillois usually associated with children, as a pleasure to be rediscovered within art. It is perhaps for this reason that the puzzle form, which refuses the serious competition of games of agôn, became important to Fluxists Brecht and Watts . Fluxus games also implicitly reject the instrumental logic of loss and gain which characterizes the capitalist economy in the late twentieth century [33].

<34> Maciunas advertised Brecht's series of ball, bead, and bread puzzles, first produced as a Fluxus edition in 1964, as "with rules...All games and puzzles invented and made to order, no two alike" (Fig. 3; Hendricks 199). In these multiples Brecht therefore expanded the event into an interactive, participatory and even tactile experience for participants who may not be Fluxus members or artists; the puzzles and games fundamentally reconfigure the spectatorial relations of Fluxus performance. In the series, one short, event-like score was sometimes placed in a puzzle box (made of plastic or balsa wood) with the object in question, possibly steel ball bearings or plastic balls; Maciunas and Brecht sometimes produced the same box and object in different versions, each with a different score included. For example, the three different Bead Puzzles with the following scores: "Bead Puzzle/Your birthday"; "Bead Puzzle/Arrange the beads so that they are the same./Arrange the beads so that they are different"; "Bead Puzzle/Cut cards so that beads do not separate./find another solution./Repeat, beyond farthest solution./G. Brecht" (Hendricks 199) [34]. Brecht also produced puzzles, which include several different scores ("Swim Puzzle/Ball Puzzle/Inclined Plane Puzzle") placed in the same box, therefore allowing the participant to choose between or vary the puzzles she or he can complete (Hendricks 197). "Swim Puzzle" was produced in boxes that included seashells, and, in one instance, a snail shell: the score for one of these works reads, "Arrange the beads in such a way that the word 'C-U-A-L' never occurs." As beads are not included in the box, the puzzle is impossible (Hendricks 201) [35].

Fig. 3, George Brecht, Bead Puzzle (c. 1965). Photo by Brad Iverson; Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Detroit, MI.

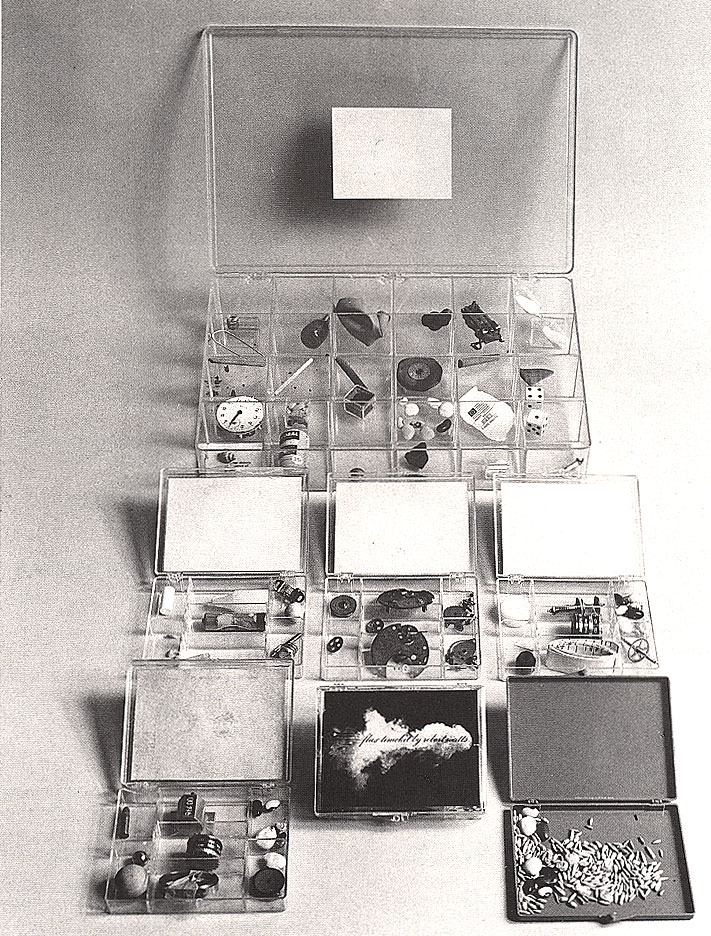

<35> Robert Watts' timekits and time puzzles presented a different challenge to the participant, which involved a meditation on temporality. First produced as "Flux timekits," and at one point included in the "Flux Cabinet" as "Time Fluxkit," and later realized in 1977 as a "time puzzle," Watts presented various elements (up to 100 of them) which were intended for the participant for "play" with, including a grided board surface on which one was to categorize and order the elements according to one's assessment of their relation to time. On the label for the "timekit" Watts printed the title over Harold E. Edgerton's famous high-speed photographic image of the trajectory of a bullet (Fig. 4). The objects he included in the time puzzle included a stopwatch, dice, a top, a rifle bullet, measuring tape, a match, and seeds which would grow at different rates (Hendricks 547-48) [36]; each object can be used to gauge the passing of time and can therefore transform the participant's sense of time -- creating a sense of disorientation from our usual sense of clocked time -- in radically compressing or slowing time down (as is the case in Edgerton's photograph, which inversely tracks a very fast event), or in greatly elongating the duration of a unit of time (in the longer-term needed for the germination of a seed and its growth into a plant). While such manipulations of temporality are well known to viewers of motion pictures, some cognitive effort is required to sort and relate the temporal aspect of these banal objects in relation to each other. Playing this game may lead to ilinx, the kind of mental disorder or temporal disorientation Caillois identified as a primitive kind of play, which can even have quasi-physical effects on the participant. Watts' "time puzzle" invites the participant to reflect on her or his own sense of the passage of time, and on their sense of mortality.

Fig.4 and 4A, Robert Watts, Flux Timekit and detail (1967).

Photo by Brad Iverson; Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Detroit, MI.

<36> Fluxus artists Yoko Ono and Takako Saito engaged with Duchamp's practice but also with masculinist cold war metaphors by taking up chess as a subject of their art. Saito's fluxchess works, which date back to 1964 but were produced as fluxus editions into the 1970s, question the primacy of vision to chess as a game of agôn-ludus, along with notions of perception and in aesthetic experience more generally. Saito's grinder, or portable chess sets, were placed in lidded hardwood chests where the grinder chess pieces, made of stone or metal, could rest in holes and remain stationary. Her "Jewel Chess" and "Nut & Bolt Chess" sets introduced materials unusual to the game, often suspended in plastic cubes, as playing pieces. But her "Smell Chess," "Sound Chess" and "Weight Chess" reworked the game of chess so that players would be forced to hone non-visual perception, such as the olfactory sense, tactility, and aurality, in order to follow chess rules. "Spice Chess" (Fig. 5), a special subset of "Smell Chess," featured different spices in test tubes as the various pieces; the players would have to learn to identify the pieces by not only vision (color and texture) but also by smell. While Saito did not dismantle the playing of the game of chess, she reminded the viewer that other senses can also be drawn upon or made to figure in the most analytical and competitive tasks or games.

Fig. 5, Takako Saito, Spice Chess (1965). Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Detroit, MI.

<37> Yoko Ono's chess works are among the most beautiful objects produced in conjunction with Fluxus; it should be noted that she contemporaneously produced her own works while others were given over to be distributed as part of Fluxus editions by Maciunas. By the late 1960s and early '70s, Ono's objects and performances were often explicitly political and frequently critical of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and of American militarism, particularly in works she realized with John Lennon. Similar to other fluxus objects, Ono's chess games rendered the process of ludus and of agôn in chess impossible and even ludicrous. Her works "Pieces Hidden in Look-Alike Containers, Chess Set"(1970, produced as a Fluxus piece) and the powerful "White Chess Set" (Fig. 6, 1971) both annihilate the possibility of competitive zero-sum play. In Ono's fluxus chess set each of the pieces is hidden in a look-alike container, making competitive play impossible. In "White Chess Set" the pieces of both players are colored white, making it impossible after a certain point to identify one player's pieces from the other. Here the metaphorical and ethical associations of black and white to evil and good are rejected; unity is underscored instead of competitive division between opponents. Ono restructures the chess game toward ilinx in disengaging properties of the game's individual pieces as determined within a game of agôn. She disengages what has been called the "internal nature" of chess, within which both an enunciating subject, the chess player, is formed, and a specific "closed" or predetermined space, one that is bordered, guarded and defended, is created [37].

Fig. 6, Yoko Ono, White Chess Set (c. 1971).

Unidentified photographer; Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Detroit, MI.

Art-Games and Cold War Space

<38> Postwar artists understood the moral and ethical importance Huizinga had earlier claimed for human play and games, a significance which Huizinga himself only recognized in studying the totalitarian state's perverse appropriation of play. The surrealists had first understood that games could reconfigure not only the creative process but also the dynamics of knowledge itself. The Cold War superpowers' politically-laden manipulation of the game -- for example, the politicization of sports within the Olympic games, and of competitive chess -- prompted a second wave of game-focused art and further theorization of games that followed the surrealists' important findings on this terrain. In their work A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari forward both an extended spatial metaphor for the condition of epistemology itself and an exercise in "nomad thought," which rejects the assumptions and the posture of political subservience that philosophy had taken on since the Enlightenment. Within this vast project, they comment on the properties of the game, specifically, on chess pieces "and the space involved." They touch upon a postmodernist cultural theory of games.

<39> Marcel Duchamp's final years of art production led the way for this widespread investigation and reclaiming of the game. Duchamp's final deployment of his own persona as a chess player ran counter to the nearly hysterical international stagings of competitive chess realized since the 1950s, which connected in obvious ways to Cold War tensions between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. The nationalism inscribed into chess reached its zenith with the World Chess championship final match between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer in 1972, though a hyper-competitive chess cult had been put in place since the 1950s around international chess matches. That chess became a shorthand sign for East/West conflict during the '60s might be proven by the fact that a chess tournament is central to the plot of the most Cold-War-fixated cultural product, the Ian Fleming 007 franchise, and the film From Russia with Love (1963) [38]. Some Cold War chess tournaments resulted in highly publicized defections to the West, as in the cases of Soviet players Viktor Korchnoi, Anatoly Lein, Vladimir Liberzon, Gannadi Sosonko and Leonid Shamkovich (Parrish 59). The propagandistic value of chess appears to have increased exponentially throughout the Cold War period. The series of photographic images of Duchamp at the chessboard contest other, widely circulated images of the playing of chess as an iconography of the balance of Cold War military power.

<40> Fahlström and Fluxus artists like Watts, Saito and Ono used the game for their strategic refusal of ludus in favor of paidia; they wrenched the game of agôn away from its functioning within the Cold-War state apparatus. In 1980, as the Cold War seemed to stretch on interminably, Deleuze and Guattari formulated a model of philosophy around the notion of "nomad thought" which they contrasted with "state philosophy", or representational thinking in service of the state. Both types of thought generate its own space of movement: state space is "striated" and "closed" in that movement is limited to predetermined and fixed lines and points. In contrast, they understood nomad thought would generate a "smooth", open space where one can move from any one point and move to any other. Not surprisingly, game theory offers up useful metaphors for their system: they discuss chess as a closed system, a "semiology," a "game of the state," an "institutionalized, related, coded war" that realizes a closed space ( Deleuze and Guattari, 352) [39]. In a move parallel to the critiques of chess that Duchamp and Fluxus had generated within visual art, Deleuze and Guattari use games to repudiate the ideology that made the militaristic Manicheanism of Cold War culture possible.

Notes

[1] Jennifer Milam, "Rococo Games and the Origins of Visual Modernism," lecture delivered at the Philadelphia CAA conference (February, 2002). Milam's book, Fragonard's Playful Paintings: Visual Games in Rococo Art, is forthcoming. [^][2] Here again the early cultural theories of games trace the footsteps of Walter Benjamin, who also addressed Schmitt, though far more positively than Huizinga, in his early essay "Critique of Violence" (1921), reprinted in Reflections. [^]

[3] In the English edition Caillois's translator Meyer Barash points to the "payola" investigations around Charles van Doren, a major scandal in the U.S. in the 1950s, as another case in point: see note 55, p. 193-4. For an expanded examination of Callois’ cultural game theory and his relation to Bataille see my essay, “Serious Play: Games and Early Twentieth-Century Modernism”, in The Space Between: Literature and Culture 1914-1945 (Fall, 2005), 9-30. [^]

[4] André Breton in Médium, II, 2 (1954), excerpted and reprinted in Gooding, 137-138; 154. Philippe Audouin, who seems to be the sole exegete of the surrealist game, followed suit in his entry of 1964 for the Dictionnaire des Jeux. [^]

[5] This list of games follows the titles attributed by Audouin and Breton. The dates given correspond to the first publication of the results of the game in question, or, the first published description of the game, as listed in Gooding 143-155. The games were mostly published in La Révolution Surréaliste and Médium, through some also appeared in Documents and Littérature. In his essay Breton does not mention the jeu de la vérité, the results of which were only first published in 1990 (French) and 1992 (English), perhaps due to their explicit nature. See Pierre. [^]

[6] This latter game, whose format is akin to that of a survey, proceeded as follows: if one were told that a particular individual had returned from the dead, would you receive her or him in your home? Breton published the statistical results, and his own elaborated responses, in order of approval. Breton's comments are noted in parentheses: Baudelaire, yes 100%; Gustave Moreau, yes, 100% ("Oui grand serrurier"); Charles Fourier yes 94%; Freud yes, 94%; Gauguin yes, 88% ("Oui avec grands honneurs"); Lenin yes 88%; Goya yes 87%; Juliette Droucet yes 87%; Hegel yes 82%; Huysmans yes 82%; van Gogh yes 76% ("Oui par égards mais avec mais, le souci d'abréger"); Seurat yes 71% ("Oui calmement en harmonie"); Marx yes 65%; Nietzsche yes 60%; Mallarmé yes 59%; Balzac yes 56%; Goethe yes 50%, no 50%; Poe no 56%; Chateaubriand no 59%; Verlaine no 87%; and finally Cézanne, no, 88% ("Non rien à se dire"). See Gooding 154, Audouin 481-2, and Breton in Médium, nouvelle série communication surréaliste No. 1, as cited in André Breton La Beauté Convulsive 411. [^]

[7] Surrealists Breton, Victor Brauner, Oscar Dominguez, Max Ernst, Jacques Herold, Wifredo Lam, Jacqueline Lamba, and André Masson began their exile from occupied France together. [^]

[8] The jeu de Marseille featured the following personages: as Genius: Baudelaire, Lautréamont, Sade and Hegel; as Siren: the Portuguese Nun (Mariana Alcoforado, 17 th-century nun whose series of love letters are now understood as forgeries), Lewis Carroll's Alice, Stendhal's Lamiel, Hélène Smith (19 th-century clairvoyant); Magus: Novalis, Freud, Pancho Villa and Paracelsus. [^]

[9] As cited by Tashjian, note 30, p. 82. In this essay Tashjian describes the events surrounding the 1963 Pasadena Duchamp retrospective staged by Hopps. Hopps' heroicizing Las Vegas story can be found in "Duchamp in Vegas," in Arman, 43-44. His statement is dated 1983, twenty years after the event took place. [^]

[10] In for example Lyotard, and Derrida's discussion of play in "Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences," in Derrida. See also Küchler. [^]

[11] Schwarz cites several sources including Truman Capote who recalls Duchamp discussing chess as an "art activity", and, via Calvin Tomkins, Edward Lasker, who reminisced about Duchamp's chess-playing style: "He would always take risks in order to play a beautiful game, rather than be cautious and brutal to win." Schwarz also quotes at length (without any citation to a source) Duchamp's comments on chess and beauty at the New York State Chess Association banquet of 1952. The entire installation behind the wood door of the Etant donnés (1946-1966) is built upon a black-and-white-tiled floor, which recalls the horizontal playing field of the chessboard. Agôn therefore remained central to Duchamp's art. [^]

[12] For a basic introduction to the Large Glass, see and Chapters 4 and 5 in Ades. [^]

[13] For a detailed summary of Duchamp's chess activity see Schwarz 57ff. [^]

[14] Bradley Bailey traces Duchamp's engagement with French mathematics in his chess- and roulette-related artworks and activities in his paper, "The Dukes of Hasard: Marcel Duchamp and the French Probabilists," delivered at the Philadelphia CAA conference, 2002, and in his dissertation, Duchamp's Chess Identity (Case Western Reserve University, 2004). [^]

[15] The multiple can be considered a medium of art which Duchamp originated in a 1917 edition of three photographs in a box. The multiple as a medium of art enjoyed a renaissance in the art of Fluxus and by the Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri during the 1960s. Where multiples or series of an artwork within an edition had been in production since the Renaissance in the form of bronzes which could be cast multiple times, or in the graphic arts with its possibility of series pulled from the same plate, object multiples following Duchamp were conceived to be manufactured by sources other than the artist. For an early consideration of the multiple see Tancock. [^]

[16] It should be noted that as early as 1936 Duchamp posed for publicity photographs playing chess; the Los Angeles Times of August 16, 1936 published a photo of Duchamp at the Arensberg's, absorbed at the chessboard, with his Nude Descending a Staircase forming a backdrop. Ironically the caption read "Artist Views Masterpiece." [^]

[17] For example, the Large Glass, Three Standard Stoppages (1914) and the Nine Malic Moulds (1914-15) were all replicas of originals produced or acquired for the Pasadena exhibition. A thoroughgoing critique of the notion of originality, and of the singular and original artwork, is certainly advanced by these works as well. The important subject of the Duchampian multiple is addressed in "Marcel Duchamp and the Multiple," in Arman 31-36; Tashjian 68-69; and by Jones 94-99. [^]

[18] Wasser in fact photographed the entire match between the two. The proof sheet has also been published in the West Coast Duchamp exhibition catalogue. See Tashjian 71-74. [^]

[19] On the relation of Duchamp's art to the history of chess see Bailey. [^]

[20] Schwarz curiously gives no other details about the Babitz/Duchamp game. [^]

[21] Babitz, who became a Southern California journalist, did finally break her silence on the match with Duchamp in a 1991 essay in Esquire. She maintains that Wasser set up the game and photo session without Hopps' knowledge, and that Duchamp made a special appearance at the Pasadena Museum to play the staged match with herself. This photograph and Duchamp's complicity in its staging is a blind spot in Jones' feminist-izing reading of Duchamp in Postmodernism and the En-gendering of Marcel Duchamp. Jones calls the Babitz/Duchamp photo "notorious" and claims that Duchamp passively acquiesced to participation. She therefore refuses to acknowledge Duchamp's role in the construction of this image; she is also uninterested in the centrality of chess to his art. [^]

[22] Arman's contribution to the Philadephia Duchamp retrospective catalogue of 1973, in which he cleverly inserted notation of a fictional game between Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy into the actual notation of a Spassky/Fischer match of 1972, underscores this final point. See Marcel Duchamp 182-184. Arman's fictional notation is also a shorthand catalogue raisonné of Duchamp's major works. [^]

[23] This definition of the game follows those of Huizinga and Caillois. [^]

[24] Robert Morris explicitly took up the game form and structure -- though defined within the realm of semiotics -- in a series of conceptual artworks that he began in 1973 entitled Blind Time Drawings. In the series and in his writings, Morris applied Ludwig Wittgenstein's notion of the language-game to the codes and sign systems set out in the art of Jasper Johns and Marcel Duchamp. Brian Winkenweder has noted that these Wittgenstenian-game-like drawings by Morris therefore systematically expand upon the language that Morris identifies as comprising "modern art." Brian Winkenweder, "Robert Morris's Blind Man's Bluff," manuscript of lecture delivered at the Philadelphia CAA conference (February, 2002) and Winkenweder’s dissertation, Reading Wittgenstein: Robert Morris’ Art-as-Philosophy (SUNY Stony Brook, 2004). [^]

[25] Caillois cites a study of the psychology of the champion by Merleau-Ponty, La Structure du Comportement, published in 1942 and almost simultaneous with Huizinga's work. The sustained engagement of philosophy, cultural theory and mathematics with the game in the twentieth century is a remarkable chapter of intellectual history. [^]

[26] Language games developed within twentieth-century modernist art, those of early surrealism, for example, lie outside the scope of this essay.Throughout the '20s and '30s the surrealists also used games as a tool of automatism and in quasi-structuralist fashion, in their explorations of representation by means of the expansion of the workings of language itself. The structuralist aspects of the word-games of earlier surrealist art have been studied, but its game-aspect has not been developed. [^]

[27] Jon Hendricks reprints the prospectus Maciunas and Watts drafted around 1967 when Maciunas purchased a number of buildings in Soho . The Greene Street Precinct, Inc. was to be a commercial and profit-generating venture, a kind of amusement arcade which was to feature shops, a discotheque, automated food establishments, and a "drink and game lounge." Many flux-games described in this essay were to be featured in the lounge. The plan apparently did not attract investors, but Maciunas continued to propose a " Flux Amusement Center " as part of fluxus exhibitions and performances. Versions of this fluxus arcade were realized in A Flux Amusement Center at Douglas College, New Jersey, in 1970, and as part of other exhibitions through 1977 (in New York City and Syracuse, in Cologne and West Berlin, Germany, and in Seattle, Washington). A consideration of how Maciunas' arcade returns to some of the spectatorial practices of primitive cinema (i.e., the "cinema of attractions" Nickelodeon connected to, for example, the late nineteenth-century Coney Island amusement park), and how it anticipates conceptual art's mode of institutional critique, would be of further interest. [^]

[28] Greenberg's influential postwar art criticism had strictly segregated play, amusement and entertainment from classical modern art. In order to champion the Kantian aesthetic tradition, Greenberg categorizes the play of amusement as part of the corrupting affect of mass culture or kitsch, which must be contested and negated within the serious realm of art. See Greenberg. [^]

[29] See Brecht. Brecht's recognition of the radicalized potential of pleasure afforded in mass culture was later violently rejected by not only Greenberg but also Horkheimer and Adorno, who maintain in the Dialectic of Enlightenment that the industry of amusément represses the masses and nothing else. [^]

[30] I discuss the connection of Fluxus to John Cage and to concrete art in West Germany in the 1950s and '60s in the first chapter of my dissertation. See Claudia Mesch, Problems of Remembrance in Postwar German Performance Art, unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago and UMI Publications, 1997. [^]

[31] See Huyssen. [^]

[32] See entries for Robert Watts in Hendricks 562-3. [^]

[33] On the rejection of instrumental reason in the work of Watts see Buchloh. [^]

[34] These works correspond to Silverman Numbers 48, 53, and 60, respectively. [^]

[35] The works correspond to Silverman Numbers 58, 58a and 59. [^]

[36] Silverman Numbers 511 ff. [^]

[37] See the comments of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in "1227: Treatise on Nomadology." [^]

[38] The demonstration board featured in the film apparently diagrams a Spassky game, lifted from a Soviet championship of 1960. See The Oxford Companion to Chess 87. [^]

[39] They contrast this "closed" aspect of chess to the Chinese game of Go and imply that Go opens onto "open" and "smooth" space. They rather force the metaphor here, as Go is, like chess, based upon and concerned with the grid as a "striated" space. Nonetheless, this metaphor is very interesting, even it they overestimate the radical difference between chess and Go. [^]

Works Cited

André Breton La Beauté Convulsive . Paris: Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1991.

Archives du surréalisme. Les jeux surrealists: mars 1921-septembre 1962 . Ed. Emmanuel Garrigues. Paris: Gallimard, 1995.

Marcel Duchamp joue et gagne . Yves Arman, Ed. Paris: Marval, 1984.

Fluxus Codex . Jon Hendricks, Ed. New York: Abrams, 1988.

The Oxford Companion to Chess . New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Ades, Dawn. Marcel Duchamp. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1999.

Audouin, Philippe. Entry of 1964. Dictionnaire des Jeux. Ed. René Alleau. Paris: Réalités de L'Imaginaire Tchou, 1964.

Babitz, Eve. "I was a pawn for art." Esquire Sept. 1991: 164-174.

Bailey, Bradley. "The Bachelors: Pawns in Duchamp's Great Game," in Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 1:3 Dec. 2000 <http://www.tout-fait.com/issues/issue_3/Articles/bailey.bailey.html>.

Benjamin, Walter. "Critique of Violence." (1921). Reflections. Ed. Peter Demetz. New York: Schocken, 1986. 277-300.

Brecht, Bertolt. "The Modern Theater is the Epic Theater (Notes to the opera Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny )". (1930). Reprinted in John Willett, ed. and trans., Brecht on Theatre . New York: Hill and Wang, 1964. 35-37.

Breton, André. Médium. II:2 (1954). Excerpted and reprinted in Mel Gooding, Ed., Surrealist Games . Boston: Shambhala Redstone Editions, 1993. 137-138; 154.

---. "Second manifesto of Surrealism" (1930). Reprinted in Manifestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969. 117-194.

Buchloh, Benjamin. "Robert Watts: Animate Objects Inanimate Subjects." Experiments in the Everyday. Allan Kaprow and Robert Watts. Events, Objects, Documents. New York: Columbia University, 1999. 7-26.

Caillois, Roger. Man, Play and Games. Trans. Meyer Barash. New York: The Free Press, 1961.

Covents, Ralf. Surrealistische Spiele. Vom "Cadavre exquis" zum "Jeu de Marseille". Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1996.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. "1227: Treatise on Nomadology." A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. 352-353.

Derrida, Jacques. "Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences." Writing and Difference . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978. 278-294.

Fahlström, Öyvind. "Notes on 'ADE-LEDIC-NANDER II' (1955-57) & some later developments." Öyvind Fahlström. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1982. 32.

---."Take Care of the world." Öyvind Fahlström. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1982. 63.

---."Games -- from 'Sausages and Tweezers -- A Running Commentary'." (1966). Öyvind Fahlström . New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1982. 58.

---."Manipulating the World." (1964). Öyvind Fahlström. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1982. 45.

Frank, Claudine. "Introduction." The Edge of Surrealism: a Roger Caillois Reader. Ed. Claudine Frank. Trans. Claudine Frank and Camille Naish. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003. 46ff.

Greenberg, Clement. "Avant-Garde and Kitsch." (1939). Reprinted in Pollock and After. Ed. Francis Frascina. New York: Harper and Row, 1985. 21-34.

Hamilton, Richard. "The Large Glass." Marcel Duchamp. Ed. Anne d'Harnoncourt and Kynaston McShine. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973. 57-68.

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens. A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Boston: Beacon Press, 1955.

Hulten, Pontus, Ed. Marcel Duchamp. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993.

Huyssen, Andreas. "Back to the Future: Fluxus in Context." In the Spirit of Fluxus, ed. Elizabeth Armstrong and Joan Rothfuss. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1993. 142-151.

Jones, Amelia. Postmodernism and the En-gendering of Marcel Duchamp. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

---. "The ambivalence of male masquerade: Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy." The Body Imaged. Ed. Kathleen Adler and Marcia Pointon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. 21-32.

Krauss, Rosalind. "No More Play." The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985. 43-85.

Küchler, Tilman. Postmodern Gaming: Heidigger, Duchamp, Derrida. New York and Berlin: Lang, 1994.

Lewitt, Sol. "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art." (1967). Reprinted in Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz, Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. 824.

Lyotard, Jean François with Jean-Loup Thébaud. Just Gaming. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985.

Maciunas, George. "Letter to T. Schmit" (January 1962). Reprinted in Götz Adriani, Winfried Konnertz, and Karin Thomas, Eds. Joseph Beuys Life and Works. Trans. Patricia Lech. New York: Barron's Educational Series, 1979. 82-4.

---. "Fluxamusement" manifesto. Reprinted in Clive Phillpot and Jon Hendricks, Fluxus. Selections from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988. 14.

McKenzie, Michael. "From Athens to Berlin: the 1936 Olympics and Leni Reifenstahl's Olympia." Critical Inquiry 29:2 (2003).

Parrish, Thomas. The Cold War Encyclopedia. New York: H. Holt, 1996.

Pierre, José, Ed. Investigating Sex. Surrealist Research, 1928-1932. Trans. Malcolm Imrie. London: Verso, 1992.

Schwarz, Arturo. "Game of precision, an aspect of the beauty of precision." The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp . New York: Abrams, 1969. 57ff.

Tancock, John. Multiples; the First Decade. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1971.

Tashjian, Dickran. "Nothing left to Chance: Duchamp's First Retrospective." West Coast Duchamp. Ed. Bonnie Clearwater. Miami Beach: Grassfield Press, 1991.

List of Figures

Fig. 1, Julian Wasser, Marcel Duchamp and Eve Babitz, 1963.

Fig. 2, Öyvind Fahlström, World Politics Monopoly (1970).

Fig. 3, George Brecht, Bead Puzzle (c. 1965). Photo by Brad Iverson; Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Detroit, MI.

Fig.4 and 4A, Robert Watts, Flux Timekit and detail (1967). Photo by Brad Iverson; Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Detroit, MI.

Fig. 5, Takako Saito, Spice Chess (1965). Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Detroit, MI.

Fig. 6, Yoko Ono, White Chess Set (c. 1971). Unidentified photographer; Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Detroit, MI.