Reconstruction 6.3 (Summer 2006)

Return to Contents»

Literal/Littoral Crossings: Re-Articulating Hope Atherton’s Story After Susan Howe’s Articulation of Sound Forms in Time / W. Scott Howard

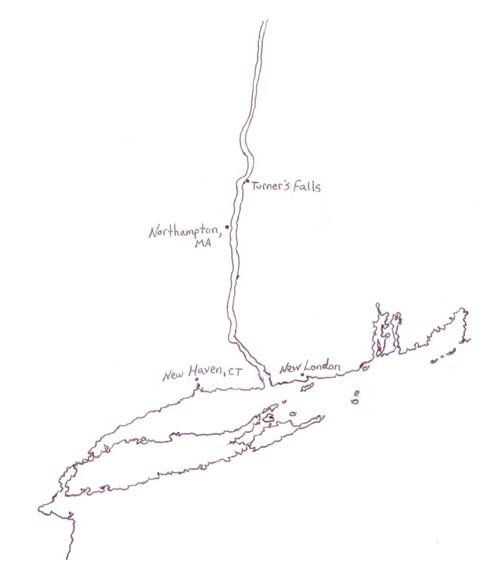

from seaweed said nor repossess rest

scape esaid[1]

<1> Water transforms everything it touches: landscapes, lives & languages. This essay offers a true relation, or a sequence of contiguous reflections—some concentric, others eccentric—provoked by the strange story of Hope Atherton (1646-77), first minister of Hatfield, Massachusetts and protagonist of American poet Susan Howe’s Articulation of Sound Forms in Time (Awede, 1987): his involvement at the battle of Peskeompscut (May 19, 1676) and separation from Captain Turner’s men during their retreat, which became a rout; Rev. Atherton’s crossings of rivers & brooks, his fearful wanderings through woods, around marshes, swamps; his near captivity, miraculous signal escapes, deliverance from Nipmucks, Pocumtucks; Hope’s subsequent return to Hadley, then estrangement in Hatfield where he would be shunned by his congregation & thus perish an outcast; also thereafter Atherton’s liminal presence in various pamphlets, books published since 1906; his enigmatic significance among literary critics lately professed, and Hope’s mystery more recently discovered by serendipitous exchanges & research. From book margins to river banks, these happenstances have confounded and transfigured me with each re-articulation.

Saw digression hobbling driftwood

forage two rotted beans & etc.

Redy to faint slaughter story so

Gone and signal through deep water

Mr. Atherton’s story Hope Atherton

<2> April-May, 1676, in the wake of the Sudbury Fight, native warriors turned their efforts from making war to tending crops. Settlers meanwhile resumed negotiations for the release of English hostages. Since the previous June at Swansea in Plymouth Colony, numerous skirmishes, raids, battles (whether planned or helter-skelter) between various tribes (Wampanoag, Pokanoket, Androscoggin and many others), settlers, colonial militia & English forces had erupted along the shores of Rhode Island and Massachusetts in the first stages of King Philips’s War (1675-77). Those conflicts soon spread to Connecticut, New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine, involving competing interests and loyalties among native groups, colonies, land investors, politicians, Christian Indians, Puritans, and English royalists in one of the most complex chapters in the early history of New England. While the Sudbury Fight was a stunning victory for the native alliance, the Battle of Peskeompscut (Great Fall) would later be known as Turner’s Falls Massacre.

scraping cano muzzell

foot path sand and so

gravel rubbish vandal

horse flesh ryal tabl

sand enemys flood sun

<3> Many tribes along the shores of the Connecticut River spoke dialects of the Algonquian language. Not all of those confederacies were united in a war against colonial, Puritan and/or English invaders, however. To the south, Mohegans generally sympathized with the Puritans. Further north, the Agawam favored the English, but turned against the colonists, violently attacking Springfield, Massachusetts on October 5, 1675. Beyond the contested & shifting boundary between Connecticut and Massachusetts, in the upper valley areas shaped by Quinetucket—the long tidal river or Great River as it was also called—the strongest native alliances were among the Nipmuc and Wampanoag, Pocumtuck, Norwottock and Nipnet.

[click map for larger version]

All of those Indians, however, lived in fear of the Iroquoian Mohawks of upper New York, who waged a sustained war (1663-80) against King Philip—Metacom, the great Wampanoag sachem—and his Algonkian followers. If not for that contemporary western, inter-tribal conflict, the nascent colonies would have suffered far greater losses.[2]

Turner’s Falls, Connecticut River, Great River, Quinetucket, long tidal river, that ancient River, the River Kishon, Great Fall, Peskeompscut, Fall River, Ash-swamp Brook, Green River, Sheldon’s Brook, Deerfield River, Bloody Brook, Hopewell Swamp.

War closed after Clay Gully hobbling boy

laid no whining trace no footstep clue

"Deep water" he must have crossed over

<4> Monday, May 15, sunup: a watchman at Hatfield spies a lone figure coming out of the woods. The man is Thomas Reed, a soldier captured near Hadley on April 1, then taken to Peskeompscut. (Reed’s track through the wilderness would ironically prove to trace the inverse path of Hope’s journey: from Hatfield, to Great Fall, in & out of ‘captivity’, through the woods and across Great River, then into Hadley and/or Hatfield). Reed had valuable information: the tribal camps around Peskeompscut included no more than sixty or seventy fighting men; and the natives were busy planting as far south as Deerfield/Dearfield. His account corroborated a narrative recently given by John Gilbert, who, in April, had escaped from his captivity at Great Fall. These reports suggested (to the English troops & William Turner) that the time may be right for a decisive strike.

It is strange to see how much spirit (more than formerly) appears in our men to be out against the enemy. A great part of the inhabitants here would our committees of militia but permitt; would be going forth: They are daily moving for it and would fain have liberty to be going forth this night. The enemy is now come so near us, that we count we might go forth in the evening, and come upon them in the darkness of the same night.[3]

Volunteers were called from Hatfield, Northampton and Hadley. Within three days Captain Turner had assembled more than one-hundred-fifty mounted men and boys. Samuel Holyoke served as Lieutenant; Isaiah Toy and John Lyman, Ensigns. Hatfield’s first minister, Rev. Atherton, served as Chaplain among the Officers. Benjamin Waite and Experience Hinsdale were Guides.

Antagonists lay level direction

Logic hail um bushell forty-seven

These letters copy for shoeing

was alarum by seaven bold some

Lady Ambushment signed three My

excuse haste Nipmunk to my loues

Dress for fast Stedyness and Sway

Shining at the site of Falls Jump

Habitants inning the corn & Jumps

<5> The militia waited for reinforcements from Connecticut, but left without them, beginning the twenty-mile march to Peskeompscut after supper, near sundown on Thursday, May 18. Hope’s wife, Sarah [Hollister] Atherton, remained in Hatfield, caring for their twin one-year-old boys, Hope, Jr. and Joseph. Sarah was also four months pregnant (with daughter, Sarah, who would be born in October). Turner was weak: suffering perhaps from his imprisonment of late by the Massachusetts Bay authorities (for professing Baptist views) or perhaps from the so-called epidemic distemper or malignant cold spreading throughout the colonies. The soldiers took a well-worn trail to Deerfield/Swamfcot, tending their progress with careful silence, keeping watch for enemy scouts.[4]

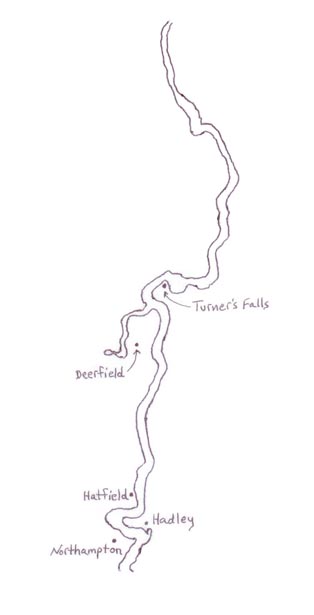

[click map for larger version]

Turner’s men, with trepidation, passed Hopewell Swamp (below Sugarloaf Hill) then crossed Bloody Brook, arriving by midnight at ravaged, abandoned Deerfield/Pecomptuck. Despite their fatigue and anxiety, the soldiers pressed on. A thunderstorm gathered and broke upon them through the early hours of Friday the 19th. The militia crossed Deerfield River at the northerly part of the meadow, near the mouth of Sheldon’s Brook, & narrowly escaped discovery at a place now called Cheapside.

These Indians, it is said, overheard the crossing of the troops and turned out with torches, and examined the usual ford, but finding no traces there and hearing no further disturbance, concluded that the noise was made by moose, crossing, and so went back to their sleep. A heavy thunder shower during the night greatly aided the secrecy of the march, while it drove the Indians to their wigwams and prevented any suspicion of an attack.[5]

That danger passed, the troops rode through Greenfield meadow, crossing Green River at the mouth of Ash-swamp Brook to the eastward. At about daybreak they reached some high ground just south of Mount Adams and dismounted, leaving their horses under light guard. The men then forded the shallow part of Fall River near the Old Stone Mill & climbed a steep hill to the crest where they waited for daylight, overlooking the Peskeompscut camps.

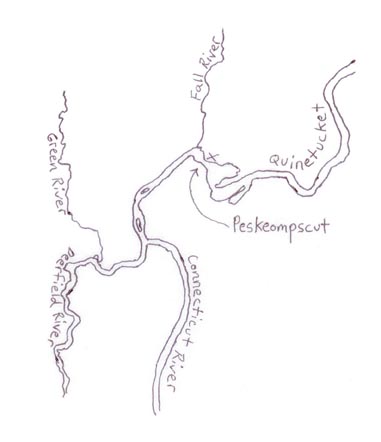

[click map for larger version]

<6> It was rumored that the Indians the night before had feasted on fresh salmon from the river, beef and new milk from cattle recently raided from Hatfield. Below the soldiers, in the native camps along the northern banks of Quinetucket, all was wrapped in sleep beside the sonorous presence of Great Fall: a frightful torrent formed by two shelving mountains of solid rock—the cataract only five yards in width, yet perhaps four hundred in length. No person was ever known to survive the passage.

[B]etimes in the morning, finding them secure indeed, yea all asleep without having any Scouts abroad; so that our Souldiers came and put their Guns into their Wigwams, before the Indians were aware of them, and made a great and notable slaughter amongst them. Some of the Souldiers affirm, that they numbred above one hundred that lay dead upon the ground, and besides those, others told about an hundred and thirty, who were driven into the River, and there perished, being carried down the Falls, The River Kishon swept them away, that ancient River, the river Kishon, O my soul thou hast troden down strength. And all this while but one English-man killed, and two wounded. But God saw that if things had ended thus; another and not Christ would have had the Glory of this Victory, and therefore in his wise providence, he so disposed, as that there was at last somewhat a tragical issue of this Expedition[.] For an English Captive Lad, who was found in the Wigwams, spake as if Philip were coming with a thousand Indians: which false report being famed . . . among the Souldiers, a pannick terror fell upon many of them, and they hasted homewards in a confused rout . . . In the mean while, a party of Indians from an Island (whose coming on shore might easily have been prevented, and the Souldiers before they set out from Hadly were earnestly admonished to take care about that matter) assaulted our men; yea, to the great dishonour of the English, a few Indians pursued our Souldiers four or five miles, who were in number near twice as many as the Enemy. In this Disorder, he that was at this time the chief Captain, whose name was Turner, lost his life, he was pursued through a River, received his Fatal stroke as he passed through that which is called the Green River, & as he came out of the Water he fell into the hands of the Uncircumcised, who stripped him, (as some who say they saw it affirm) and rode away upon his horse; and between thirty and forty more were lost in this Retreat.[6]

rest chondriacal lunacy

velc cello viable toil

quench conch uncannunc

drumm amonoosuck ythian

_______

scow aback din

flicker skaeg ne

barge quagg peat

[T]hey fired amain into their very Wigwams, killing many upon the Place, and frighting others with the sudden Alarm of their Guns, and made them run into the River, where the Swiftness of the Stream carrying them down a steep Fall, they perished in the Wa-ters, some getting into Canoes, (Small Boats made of the Bark of birchen Trees) which proved to them a Charons Boat, being sunk, or overset, by the Shooting of our Men, delivered them into the like Danger of the Waters, giving them thereby a Passport into the other World: others of them creeping for Shelter under the Banks of the great River, were espied by our Men and killed by their Swords; Capt. Holioke killing five, young and old, with his own Hands from under a Bank. When the Indians were first awakened with the Thunder of their Guns, they cried out Mohawks, Mohawks, as if their own native Enemies had been upon them; but the dawning of the Light, soon notified their Error, though it could not prevent the Danger.[7]

Impulsion of a myth of beginning

The figure of a far-off WandererGrail face of bronze or brass

Grass and weeds cover the faceColonnades of rigorous Americanism

Portents of lonely destructivismKnowledge narrowly fixed knowledge

Whose bounds in theories slayTalismanic stepping-stone children

brawl over pebble and shallowMarching and counter marching

Danger of roaming the woods at randomMen whet their scythes go out to mow

Nets tackle weir birchbarkMowing salt marshes and sedge meadows

On the 18th of May, a party of one hundred soldiers marched silently in the dead of night to Deerfield, to attack a party of Indians stationed there. They surprised them about break of day, and succeeded in killing about three hundred men, women, and children. The Indians soon after rallied and attacked the party, killing Captain Turner, the commander of the expedition, and thirty-eight of his men.[8]

The danger of the waters touched everyone, granting unto many passports into other worlds. Just as the panic-terror of one captive English boy (King Philip!) provoked a tragic outcome for Turner’s men, a reciprocal misrecognition sparked by fear (Mohawks!) drove the Indians into battle.

<7> During the rout, Samuel Holyoke, Turner’s second-in-command, attempted to organize the chaos. Protecting flank and rear, trying to avoid ambuscades, Holyoke led the terrorized men onward to a place known as the Bars on the south side of Deerfield meadow. One soldier, John Belcher, struggling on one good leg, was rescued by Isaac Harrison, who took up Belcher on his horse. After a short distance Harrison was wounded and slid off his horse to rest. Belcher galloped away despite Harrison’s pleading cries & etc. Nearly all the troops eventually returned to Hatfield later on Friday. Forty-four or forty-five (including Hope) were separated in the melee, becoming lost in the woods for several days.[9] Over the next four days, six of the missing wandered into Hatfield. Jonathan Wells of Hadley arrived on Sunday.

Rev. Mr. Russell’s letter of May 22 nd gives some account of the losses, and says that six of the missing have come in, reducing the number of the lost to thirty-eight or thirty-nine. Of the Indian losses he gives the report of Sergt. Bardwell that he counted upwards of one hundred in and about the wigwams and along the river banks, and the testimony of William Drew and others that they counted some "six-score and ten." "Hence we cannot but judge that there were above two hundred of them slain."[10]

Tallies of the dead, wounded, missing, lost & returned vary from one document to another. The massacre at Great Fall would soon be seen by many officers, soldiers and citizens as one of the greatest atrocities committed by the English and the colonists in the war against Metacom. For the Algonkin tribes, Peskeompscut became a rallying cause, prompting several reprisals well into the future, including a major assault in 1704 (on February 29) against Deerfield/Squakeag.[11]

[click image for larger version]

<8> Atherton and the others roamed the woods at random—desperate for their lives, climbing trees, hiding behind rocks, sleeping beneath mounds of leaves. Some eventually surrendered to the Indians. The warrior groups of Squakeags, Nipmunks, Pokomtucks and Mahicans spared only Hope, covering the others with dry thatch, which they set afire. Those flaming, smoldering soldiers were forced to run until death dispatched them. Rev. Atherton, dressed in his black coat without a hat, seemed a strange creature. He spoke such language as he thought the natives understood. Fearing that he was the Englishman’s God, the Indians kept their distance, permitting Hope’s escape.[12] Few documents recount Atherton’s return at noon on Monday, April 22. One letter signed by Aaron Cook to the authorities at Hartford attests to Hope’s arrival at Hadley;[13] another letter, written by Stephen Williams, conveys a corroborative report by Jonathan Wells, Esq., who participated in the raid at Great Fall.

In the fight, upon their retreat, Mr. Atherton was unhorsed and separated from the company, wandered in the woods some days and then got into Hadley, which is on the east side of the Connecticut River. But the fight was on the west side.[14]

As rumor spread, citizens of Hadley and Hatfield grew incredulous of Rev. Atherton’s professed deliverance from the Indians & improbable (if miraculous) solo crossing of Quinetucket. Many suggested he was beside himself. Through his own accounts—briefly stated first in a sermon (Sunday, May 28) then more elaborately set forth in a written narrative for his congregation—Hope sought to allay any suspicion about his experience and credibility.[15] In his sermon, Atherton accordingly claimed Hatfield (not Hadley) as his point of return.

In the hurry and confusion of the retreat I was separated from the army. The night following, I wandered up and down, but none discovered me. The next day I tendered myself to the enemy as a prisoner, but, notwithstanding I offered myself to them, they accepted not my offer. When I spoke they answered not; when I moved toward them they fled. Finding that they would not accept me as prisoner, I determined to take the course of the river, and if possible find my way home; and after several days of hunger, fatigue and danger, I reached Hatfield.[16]

Hope’s testimonial divulges his moments of providential guidance, including his inexplicable fording of the Connecticut River—thus alternately suggesting his arrival at Hadley (not Hatfield). Rev. Atherton’s contradicting, mysterious ‘crossings’ of Quinetucket may have signaled his escape from the wilderness as well as his imminent exclusion from his community.

Hope Atherton desires this congregation and all people that shall hear of the Lord’s dealings with him to praise and give thanks to God for a series of remarkable deliverances wrought for him. The passages of divine providence (being considered together) make up a complete temporal salvation. I have passed through the Valley of the Shadow of Death, and both the rod and staff of God delivered me. A particular relation of extreme sufferings that I have undergone, & signal escapes that the Lord hath made way for, I make openly, that glory may be given to him for his works that have been wonderful in themselves and marvelous in mine eyes, & will be so in the eyes of all whose hearts are prepared to believe what I shall relate . . . I spoke such language as I thought they understood. Accordingly I endeavored; but God, whose thoughts were higher than my thoughts, prevented me, by his good providence I was carried beside the path I entended to walk in, & brought to the sides of the great river, which was a good guide unto me . . . Two things I must not pass over that are matter of thanksgiving unto God; the first is that when my strength was far spent, I passed through deep waters & they overflowed me not, according to those gracious words of Isa. 43, 2; the second is that I subsisted the space of three days & part of the fourth without ordinary food. I thought upon those words "Man liveth not by bread alone but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of the Lord" . . . I am not conscious to myself that I have exceeded in speech. If I have spoken beyond what is convenient, I know it not . . . God’s providence hath been so wonderful towards me, not because I have more wisdom than others (Danl. 2, 30) nor because I am more righteous than others; but because it so pleased God.[17]

On the following Tuesday, May 30, approximately seven hundred warriors of the confederated tribes struck Hatfield: twelve houses & a barn were burned to the ground. Atherton survived the raid, but became increasingly traumatized and died a pariah the following year, June 8, 1677.

Loving Friends and Kindred: —

When I look back

So short in charity and good works

We are a small remnant

of signal escapes wonderful in themselves

We march from our camp a little

and come home

Lost the beaten track and so

River section dark all this time

Hopewell Swamp, Bloody Brook, Deerfield River, Sheldon’s Brook, Green River, Ash-swamp Brook, Fall River, Peskeompscut, Great Fall, the River Kishon, that ancient River, long tidal river, Quinetucket, Great River, Connecticut River, Turner’s Falls.

<9> According to Susan Howe, no one believed Hope Atherton’s particular relation of extreme sufferings. "He became a stranger to his community and died soon after the traumatic exposure that has earned him poor mention in a seldom opened book."[18] Why was Atherton’s narrative deemed untrustworthy? Why was Hope shunned? The historical documents are silent on those matters. There was not a lack of precedent (in Hatfield) for either accounts of captivity or crossings of Great River, as the story of Thomas Reed (noted above) illustrates. However, whereas Reed was transported by canoe, Atherton audaciously claimed divine intervention: "I passed through deep waters & they overflowed me not." His literal/littoral explanations risked all hope of believability.

Bound Cupid sea washed

Omen of stumbling

Great unknown captaincycenturies roam audible silence

With hindsight, one may see that Atherton’s narrative anticipated some of the emerging rhetorical motifs of the true relation, or captivity narrative: typological interpretations of decisive, inexplicable events; causal relationships between the workings of Christ’s grace, God’s special providence & the captive’s release; and analogies between the captive’s return and the consequent promise of salvation for the faithful among the reading public.[19] Hope’s testimony, though, was published six years before Mary White Rowlandson’s The Soveraignty & Goodness of God (1682), which was so popular—as a foundational myth-making text about the American frontier—that all available copies of the volume’s first edition were literally read to pieces.[20] Atherton’s story challenged the tacit logic of the status quo, advancing claims both dishonorable—that he tried repeatedly yet in vain to surrender himself—and temeritous, especially the autotelic application of Isaiah 43.2 ("When thou passest through the waters, I will be with thee: and through the rivers, they shall not overflow thee")[21] to his purported fording of Quinetucket.

Untraceable wandering

the meaning of knowingPoetical sea site state

Abstract alien point

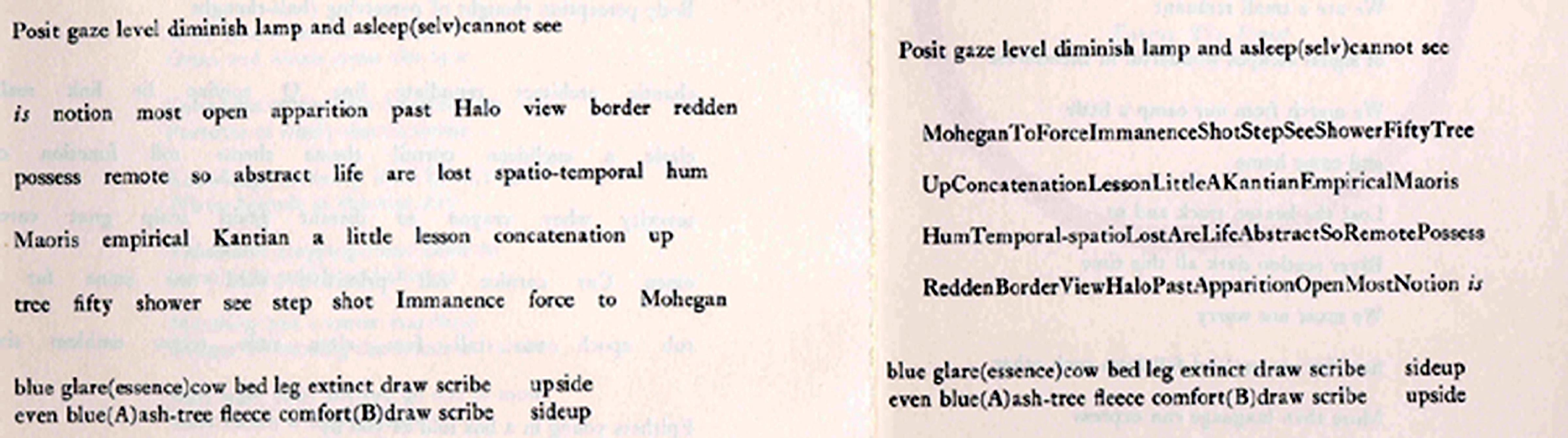

<10> Hope’s baptism through deep water irrevocably altered him. His story has engendered a cluster of intertextual allusions/elisions/illusions among the essays written by scholars of American poetry and poetics in response to Howe’s reconfiguration of Atherton’s mid-life transformation.[22]Articulation of Sound Forms in Time and the second edition of that chapbook-length poem published in Singularities (Wesleyan, 1990) offer linguistic collages that question what remains ultimately unknowable within and against the aleatory course of history. Her "Collision or collusion with history" traces a "Migratory path to massacre", shadowing "Sharpshooters in history’s apple-dark". The possible answers to those questions are more than multiple, contradictory and all simultaneously true and false, absent and present. There is neither beginning nor ending to the riddle of Rev. Atherton, his crossing of rivers, swamps & brooks.

Mackerel sky

wind-ripples

Yet Howe’s pages continue to draw readers into the shallows and swifter currents of times past and present, prompting further research, as the poet herself was likewise compelled to return to the lives & events that shaped the battle at Peskeompscut, thereby adding one more layer of historical inquiry—a new preface titled "The Falls Fight"—to the republished version of her work in Singularities. The rush of the falls: the pull of the river, the drift of stories.

Occult ferocity of origin

each winged ambition

sand track wind scatterInarticulate true meaning

<11> I do not wish to dispel the myths at the centers and circumferences of these lives, events & their relations. Critics have engaged with Howe’s text, yet none have also equally considered the historical moment. Why was Hope’s testimony not believed? Why was he subsequently treated as a pariah within his own community? And why, in the first place, was Atherton involved in the massacre? Those questions have persisted for Howe’s critics, as they have for me since 1990 when I first encountered her Articulation. I had not before read any of Susan Howe’s poetry. When I held the book from Awede Press for the first time, I was simply confounded by her work’s form and content. As I began to grasp Howe’s lyrical and trans-discursive poetics, I became increasingly fascinated (and disturbed) by the Turner’s Falls massacre. After many re-readings and further research, I have come to understand that Howe’s poem is just as intractable & resilient as Hope’s experience and the events prior to, during and consequent from the battle at Peskeompscut. I wish to trespass upon neither the contingency nor the indeterminacy of any of those contexts. And yet, by re-reading and writing/revising, I am also re-articulating, crossing the river yet once more, following Hope after Howe.

Shoal kinsmen trespass Golden

Smoke splendor trespass

I want to create a companionate text—a work that replies in kind, meeting language with language, collage with collage—an essay that celebrates what remains singular and unknowable about these matters. Each time I return to these documents, looking for more clues about Rev. Atherton’s journey through the landscape, I lose and later rediscover myself in the pursuit. On this occasion, I have also tracked Howe’s riparian path, offering a sequence of her lines closest to the waters.

Outline was a point chosen

Outskirts of ordinaryWeather in history and heaven

Skiff feather glide houseFace seen in a landscape once

<12> From the shores of rivers to the margins of books, these events and documents continue to haunt me. In 1993 I was working at Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon (near the banks of the Willamette River), preparing a paper on Susan Howe’s Articulation of Sound Forms in Time that I would later present at a cultural studies conference at the University of Oregon.[23] I wanted to find answers to those persistent questions about Hope Atherton that have continued to stump the critics. Why was his testimony discredited? Why did he become an outcast? Why was he involved in the massacre? I was talking about these things with Mark Johnson, when he suddenly took my arm: "You’re not going to believe this." Just the previous day, Mark had been unpacking books from boxes damaged by water leaking through one of the warehouse roofs. One particular volume caught his eye because the spine was blank: Hope Atherton and His Times: A Paper Read by Arthur Holmes Tucker (Deerfield: Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, 1926). Only fifteen libraries worldwide own copies, none of them west of the Mississippi. I was awestruck by the serendipity, although such uncanny discoveries at Powell’s were not entirely uncommon during the 1980s and early 90s—prior to the era of computerized inventory. (To the best of my knowledge, none of Howe’s critics, to date, have ever cited Tucker’s publication despite the fact that a citation record for Hope Atherton and His Times may be easily found, via a simple keyword search, through WorldCat, the world’s largest bibliographic database). How do these things happen? Why have I been waiting to write this essay since 1993? Justin Scott-Coe and I first met one another at the Huntington Library in March, 2005 at a joint meeting of the South-Central Renaissance Conference (SCRC) and the Renaissance Conference of Southern California (RCSC). We were each momentarily lost, dazed in the sunlight on the terrace, seeking the location for an upcoming panel session on "Witchcraft in Early Modern England." With our official-looking conference maps in our hands, we began talking and walking. Justin said he was preparing to organize a special issue of Reconstruction on the topic of water. I said I had an essay (ready for revision) and a story to tell. There’s a mystery in all of this that I want to respect—a persistent force of waters, rivers, landscapes, lives & languages.

And so ends this story of Hope Atherton and his times; meagre enough as to details of his own experiences, because of the loss of the records of Hatfield covering almost the entire period of his ministry. But we can feel assured, though life was cut short in the time of his early manhood, that he had stood faithful to life’s tasks as they came to him year by year.[24]

<13> Endings are beginnings. Tucker’s volume includes transcriptions of Hope’s sermon and extended narrative as well as an account of the battle at Peskeompscut. The book also provides some valuable genealogical and biographical information that has led me to a hypothesis for Rev. Atherton’s involvement at the massacre. While it was not uncommon at all for chaplains to accompany soldiers on their errands of war during the seventeenth century in New England, Atherton may have had other business interests to represent at the falls fight. Hope’s father was Major General Humphrey Atherton (of Dorchester, Massachusetts) who owned the Atherton Company—a group of Puritan land investors (from Massachusetts and Connecticut) that included John Winthrop, Jr. (governor of the Connecticut colony from 1659-76) and Captain William Turner. (Atherton & Winthrop were among the company’s founding partners).[25] Following the accidental death of Hope’s father in 1661, the Atherton Company was in flux, seeking new opportunities.

The Hatfield records are missing for the four years 1673-7. This was the active period of Hope Atherton’s ministry, and we are unfortunately left in ignorance of what happened there during that entire time.[26]

<14> Rivers were vehicles for conquest and resistance. Titles to the territories along both sides of the Connecticut River were contested during (and long after) the 1660s. West of the river, Connecticut and New York battled over claims; to the east, Connecticut and Massachusetts. Farther to the north—above today’s border between Massachusetts and Vermont/New Hampshire—French Canada vied for position. (A group of forty-seven French Canadians and perhaps as many as two hundred Abenaki, Pennacook, Mohawk, and Huron allies collaborated in the 1704 attack on Deerfield). Along the eastern banks of Quinetucket from the Atlantic coast to Peskeompscut and beyond, boundary disputes were particularly fierce. All of those competing interests, of course, were further aggravated and destabilized by native alliances with King Philip/Metacom (against the English and Puritan colonists) as well as by the Iroquoian Mohawk war (against the Algonquians) which, in turn, was perniciously fueled by the aggressive policies of the Duke of York and Edmund Andros—appointed in 1674 to govern the New York colony—in their territorial battles (against Governor Winthrop & the colony of Connecticut). In 1647 Winthrop had claimed the lands between the Connecticut and Niantic Rivers stretching northward from the coast. John Winthrop, Jr. died on April 5, 1676—less than seven weeks before the assault on Peskeompscut—leaving the Atherton Company in the hands of the remaining investors, which included William Turner, against the rising powers of York and Andros. Was Rev. Atherton among those land investors in 1676? Was Hope acting with Turner to represent his father’s concern, the Atherton Co., at the falls fight, hoping to extend the legacy of Winthrop’s land acquisitions along the eastern banks of the Connecticut River from the Western Niantic Country north to Deerfield & then to Great Fall?

The story of Hope Atherton and his times, here given, contains nothing new, nothing that has not been told. From many sources, however, have been picked up the records of events intimately touching not only the life of this man, which, though short in years, extended through a period as stirring as any in the story of New England, but also the customs and daily life of the colonists in his day.[27]

<15> "Ask of me, and I shall give thee the heathen for thine inheritance, and the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession."[28] Long before the influential work of W. J. McGee, who argued in 1909 that the "conquest of nature . . . will not be complete until [water resources] are brought under complete control,"[29] the land was stolen, bought, sold and ‘civilized’ along the shifting fault lines of cultural, political, racial and religious ideologies. Husbandry Spiritualized, a popular volume of religious meditations by John Flavel published in Boston in 1709, for example, expounded upon the "heavenly use of earthly things."[30] Winthrop, Jr. received many gifts from his father, John Winthrop, Sr., Governor of Massachusetts (1588-1649), including an insider’s understanding of what we today would call natural resource management law.[31] In 1629 John Winthrop, Sr. authored a binding document that held that "most land in America fell under the legal rubric of vacuum domicilium because the Indians had not ‘subdued’ it and therefore had only a ‘natural’ and not a ‘civil’ right to it."[32] That premise was used on countless occasions by Puritan colonists & investors in Massachusetts and Connecticut to obtain parcels of land from various native tribes. The Atherton Company (with John Winthrop, Jr.) engaged that rationale in their fraudulent acquisition of "six thousand acres of the best Narragansett land from sachem Pessicus’s feeble-minded younger brother" in 1659.[33]

The English bible was the one book familiar to all, read and studied by every household, till its language became the language of the street, the market, and the place of public assembly, as well as the house of worship, the model of written expression in letters, petitions, and legislative utterances, as well as the basis for sermons.[34]

<16> Peskeompscut was widely-known among the English soldiers, Puritans and colonists to be a bountiful fishing place. In the spring of 1676, the people of many Algonkian tribes (Nipmuc, Wampanoag, Pocumtuck, Norwottock & Nipnet) were planting crops and harvesting food from Great Falls to Deerfield according to their ‘natural’ rights. Would William Turner and Hope Atherton have planned their attack with such nuanced ‘civil’ reasoning? Was it mere coincidence that they were both connected to the Atherton Company and thereby implicated (perhaps) in the on-going rivalry between Winthrop, Sr. (Massachusetts), Winthrop, Jr. (Connecticut) and Andros (New York)?

Archaic presentiment of rupture

Voicing desire no more from hereFar flung North Atlantic littorals

Lif sails off longing for life

Baldr soars on Alfather’s path

<17> There’s no end to these questions, no still center or circumference to this story. The course and significations of Quinetucket and Peskeompscut continue to change and be changed. After the massacre, a rumor grew into the legend of a native squaw who survived a solitary trip over the deadly falls in a canoe, having found her courage in a jug of rum.[35] In 1918, on the site of Great Fall, a hydro-electric dam was built that soon produced two-thirds of the electricity used by western Massachusetts businesses.

Rubble couple on pedestal

Rubble couple Rhythm and PedestalRoom of dim portraits here there

Wade waist deep maidsworn menCrumbled masonry windswept hickory

Notes

[1] Susan Howe, Articulation of Sound Forms in Time (Windsor, VT: Awede, 1987). Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Howe’s poem will correspond with this un-paginated letterpress edition. Those sequential passages from her Articulation, as this first quotation suggests, will be consistently justified with a two-inch, left indentation. Passages from other source texts will be consistently justified with a one-inch, left indentation. Through those and several other stylistic gestures, I hope to shape an essay composed of imbricate discourses—parallel (sometimes overlapping) yet differentiated—in dialogue with one another. [^]

[2] Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias, King Philip’s War: The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict (Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press, 1999), 1-57, 143-233; and Francis Jennings, The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (New York: Norton, 1976), 313-26. [^]

[3] William Turner’s letter (April 29, 1676, Hadley) to the General Court; included in: George Madison Bodge, Soldiers in King Philip’s War: Being a Critical Account of That War with a Concise History of the Indian Wars of New England From 1620-1677 (Boston, 1906), 242. [^]

[4] Schultz and Tougias, 220-26. Douglas Edward Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk: New England in King Philip’s War (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., 1958), 199-207. [^]

[5] Bodge, 245. [^]

[6] Increase Mather, A Brief History of the Warr with the Indians in New-England (Boston, 1676), 30. [^]

[7] William Hubbard, A Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians in New-England (Boston, 1677), 230-31. [^]

[8] William Moore, Indian Wars of the United States From the Discovery to the Present Time (Philadelphia: J. & J. L. Gihon, 1852), 131. [^]

[9] Leach, 199-204. Bodge, 244-47. [^]

[10] Bodge, 247. [^]

[11] James D. Drake, King Philip’s War: Civil War in New England, 1675-1676 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 133, 234 n. 56. [^]

[12] Susan Howe, "Articulation of Sound Forms in Time," Singularities (Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1990), 5. [^]

[13] Arthur Holmes Tucker, Hope Atherton and His Times (Deerfield: Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, 1926), 66. [^]

[14] Howe, Singularities, 5. [^]

[15] Howe, Singularities, 3-5. Tucker, 62-72. [^]

[16] Tucker, 66-7. [^]

[17] Tucker, 67-70. [^]

[18] Howe, Singularities, 4. [^]

[19] Richard Slotkin and James K. Folsom, eds., So Dreadfull A Judgment: Puritan Responses to King Philips’s War, 1676-1677 (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press), 301-14. [^]

[20] Only four tattered pages survive. Jill Lepore, The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), 149; and Frank Mott, Golden Multitudes: The Story of Best Sellers in the United States (New York: Macmillan, 1960), 303. [^]

[21] The Holy Bible: King James Version (New York: Meridian, 1974), 580. [^]

[22] Consider the following articles, for example: Susan M. Schultz, "The Stutter in the Text: Editing and Historical Authority in the Work of Susan Howe," However 1.6 (2001); James McCorkle, "Prophecy and the Figure of the Reader in Susan Howe’s Articulation of Sound Forms in Time," Postmodern Culture 9.3 (1999); and Marjorie Perloff, "‘Collision or Collusion with History’: The Narrative Lyric of Susan Howe," Contemporary Literature 30.4 (1989): 518-33. [^]

[23] "Anecdote as Reflexive Field in the Poetry of Susan Howe," Practicing Postmodernisms: May 7, 1993, University of Oregon. [^]

[24] Tucker, 72. [^]

[25] Susan Howe, The Birth-Mark: Unsettling the Wilderness in American Literary History (Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), 121. Jennings, 254-326; Leach, 14-29; and Tucker, 1-9, 62-3. Howe’s text briefly notes the business connections between Humphrey Atherton and John Winthrop, Jr., but neither cites Tucker’s volume, nor links Hope to his father, Humphrey, nor connects Turner to the Atherton Co. Jennings and Leach provide detailed accounts of the Atherton Company’s dealings in the 1660s. Tucker’s biographical information links William Turner to Humphrey Atherton. [^]

[26] Tucker, 9. [^]

[27] Tucker, 1. [^]

[28] Psalms 2.8, The Holy Bible: King James Version (New York: Meridian, 1974), 466. [^]

[29] W. J. McGee, Water as a Resource: Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 33 (1909): 522-23. [^]

[30] Flavel, 27: "You have Evidences for your Estates, and by them you hold what you have in the World." [^]

[31] For example: in 1640 Winthrop, Sr. gave to his son dominion over Fishers Island, where I grew-up. Now part of Suffolk County, NY, Fishers Island lies approximately eight miles out from the mouth of the Thames River, which, during the early seventeenth century, was known as the Pequot River. [^]

[32] Jennings, 82. [^]

[33] Jennings, 278-79. [^]

[34] Tucker, 49. [^]

[35] Tucker, 64: "This woman had undertaken to cross the river . . . , having in the canoe a jug of rum, which she intended to convey to the opposite shore. But the canoe was drawn into the swift current, and carried down the frightful gulf. While the squaw was thus hurrying to certain destruction, as she had every reason to believe, she seized upon her jug of rum, and did not take it from her mouth until the last drop was quaffed. She was marvellously preserved from death, and was actually picked up, several miles below, still floating in the canoe, and quite drunk." [^]