Reconstruction 6.3 (Summer 2006)

Return to Contents»

Being Boat / Basia Irland

[The following is a chapter from Water Library, a forthcoming book to be published by the University of New Mexico Press.]

I’ve always felt that boats are among the most elegant of human creations, perhaps because they’re designed in close collaboration with nature – to flow easily through water, to ride on turbulent seas, to shed or harness the wind.

- Richard Nelson, naturalist, author (The Island Within)

Prelude

Jeroen van Westen, Dutch interdisciplinary water artist

‘Maybe you know.’

‘What?’

‘Where the eyes of the sea are.’

‘Because, she does have eyes, right?’

‘Yes.’

‘And where the hell are they?’

‘The ships.’

‘What about ships?’

‘Ships are the eyes of the sea….’

- Allessandro Barrico, playwright (Ocean of the Sea)

Reading the Current

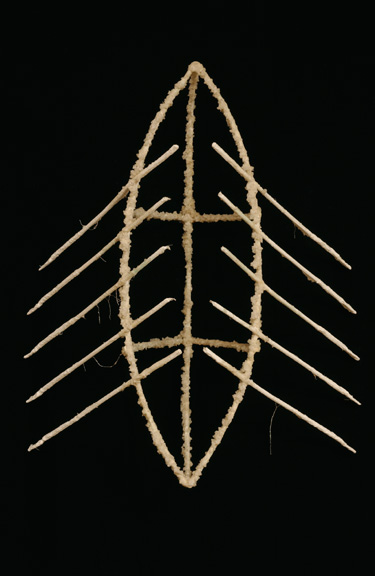

<1> Seaweed and lichen hanging from Basia Irland’s vessels suggest these structures travelled both water and earth. We all know boats aren’t made to cross over mountainous, rocky types of landscapes where lichens grow. We have to think about these vessels as metaphors. The physical resemblance of the basic construction of a hull to a ribcage connects the ship to organic life, to people, and in Irland’s suspended sculptures, analogies are demonstrated between humans, sea fish, and sea mammals.

<2> Basia’s skeletons of boat hulls no longer contain worldly goods. What is left is the spiritual meaning of the voyage. Her hulls are natural outcrops of the basic construction; they suggest transformational qualities of the ships she has found in her imagination. The hulls reference destinations or voyages the vessel has known.

<3> In this culture, people depend heavily on instruments to understand our environment. We listen to the weather forecast before we go out sailing, and we bring a compass or Global Positioning System. However, when I am sailing in the waters around Holland, it is the tremble of the hull or the shudder in the rudder that announces the wind is picking up speed. The tiny ripples on the slightly larger waves warn of extra wind. In a kayak, the resistance on a paddle reassures you are still in balance. Body and boat have to be one, and it is as if you are part of the water you are riding. Lying quietly in a kayak in Johnstone Strait, British Colombia, Canada, an orca swam up close to the kayak. The kayak became an extension of my body, mediator between the sea and me.

<4> The suspended boat is a symbol for putting your life in the hands of the great unknown, a force that has purpose and meaning beyond our personal understanding. In small churches in Norway and Brittany ( France), I saw such ships hanging in the air by thin threads near the altar. The roofs of these churches are often constructed exactly like the ships made in the same village. Still water reflects the sky, day and night. It is a vertical connection for all who sail the horizontal waters.

<5> Basia’s projects are not about water, but about the role water plays in our culture, how water has structured humankind, and how water can be a catalyst for cultural change. Her work explores ways to understand our connection to nature, but grounded in a very realistic taking responsibility. Her work is not anthropocentric, but the opposite. She acknowledges that the gap between nature and culture is only perception, an attitude, or a conceptual construct, which she intends to subvert.

<6> The boat is a means to overcome the gap between language as we humans developed, and the (possible) universal language of nature. The rafting guide who reads the current and survives the white water rapids demonstrates an ability to understand nature’s ‘language’. Looking at Basia’s boats, we become seafarers, guided by a wish to understand, an invitation to stretch our minds.

Interview

<7> This interview between Irland and David Williams, a British author, professor, and performance artist took place in an outdoor cafe by the sea in Dartmouth, England, early 2006.

<8> David Williams: It’s evident you have a fascination for boats, connected to your interests in water and journeys. The boats you’ve made are somewhat anthropomorphic, structurally reminiscent of ribcages, and they interpenetrate human and animal in both form and materials.

<9> Basia Irland: I love canoeing. It has been my primary means of transportation for many of the water projects. There’s something very serene about being out on the water of a lake when it is calm. Rivers can be little less predictable: I’ve capsized several times and it can be scary. I enjoy the physicality and practicality of traveling by means of self-propulsion on water. It’s a kind of swimming.

<10> Some of my sculptural boats were indeed anthropomorphized or had animal aspects. Some had fish tails: A lot of them had wings. I like the image of a winged boat. In some cultures, boats are the carriers of the soul, just as the crescent moon was seen as a boat form with a similar function. And I’m also drawn to paddles, sculpturally, and their relationship to the human body, a kind of extension of the arm.

<11> DW: Your boats often float in the air. They are present and absent, line drawings of vessels that may have been there once, or are yet to come. They are both gravity-bound and airborne. For me, they are reveries, invitations to travel, connecting up with all sorts of notions of journeying.

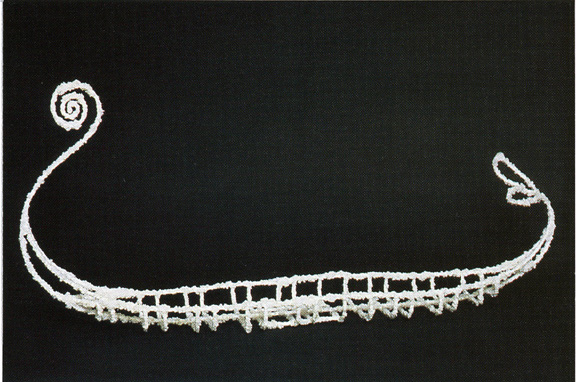

<12> BI: When I originally made the suspended boat pieces in Canada, they were bent willow covered with light-emitting diodes sited in a darkened environment. I was creating my own constellations. At the Center for Contemporary Art in Santa Fe, I suspended forty boats, made from welded black wire covered with salt crystals, in an open atrium area three floors high. The boats cast distinctive shadows.

Reflections

<13> Row your boat . One of the most evocative images is that of the floating vessel. Its shape conjures thoughts of travel, commerce, and refuge. Boats are the tools of exploration, food gathering, recreation, transportation and celebration. The form and size vary, but each serves a function for a specific location and culture: traditional dhows plying the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea, Viking ships, rowboats, Balinese double outriggers, Venetian gondolas, Inuit kayaks, and wooden dugouts of the Carib Indians. The lashed totora-reed boats of the Uros people of Lake Titicaca in Peru are similar to the Egyptian boats built from reeds found growing along the Nile. I am most intrigued by handmade craft powered by paddle, oar, or pole. The physical act of rowing or paddling establishes a cadence within the body. In an Orion Magazine article, “It Flows Along forever,” Ann Zwinger describes how, “Rowing engenders a lovely rhythm that matches my breathing; rowing takes its essence from the current, glues me to the cadence of the river.”

Though you, in spirit, I know are still a canoe.

Michael Ondaatje, Canadian writer (The English Patient)

<14> My love of being in a boat on water came from seventeen years of living in Canada. Derek, my son, grew up in a canoe, exploring lakes in the wilds of Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario. Afraid of the leaches on shore, he learned how to climb in and out of a canoe in deep water at an early age – no easy task. The camping, black flies, and long portages were all part of the experience.

<15> There is a difference between lake and river canoeing. On an open lake, one usually moves against a head wind, or fights choppy waters. On a river, one must constantly watch for rocks, eddies, or steep inclines, but you also go with the flow of the current. Now that I live in the high desert of New Mexico, my canoe sits in the back yard with its tongue hanging out, wondering where the large lakes have gone. Here there are very few natural lakes. Most are reservoirs behind dams, human constructions that have occurred quickly, not formed over long periods of time. Upon arrival in New Mexico, we used to swim at Abiquiu Reservoir, but it was a bizarre experience because you were swimming over the tops of trees that had once breathed mountain air and were now submerged! I always wondered what else was down there below the surface.

<16> During the 2005 summer solstice, under an enormous, radiant yellow full moon, nine of us formed a motley flotilla down the Río Grande through the outskirts of Albuquerque, from eight-thirty at night until take-out at midnight. Usually we would have to pull the boats this time of year, when the water level is low and the Río Grande is not grand at all. But this season the river through the Albuquerque reach is running at about 5000-6000 cubic feet per second (CFS): a normal CFS for this time of year would be less than a thousand. While floating the river in two inflatable kayaks, three river kayaks, and one canoe, we ate sushi, drank beer, enjoyed Mescal with lime, and howled at the moon. The most intrepid kayakers would tip their boats upside down, beer in hand, and manage not to spill any while coming back up from under water. The day had been overcast and rainy, but at dusk the sky cleared, and on this longest day of the year, the moon was so bright we could see obstacles up ahead in the current.

<17> Inflatables. In New Mexico, rafting adventures down the Río Chama and along the Río Grande near Taos have replaced my Canadian canoe trips. I often take my university art classes rafting. We float downstream and bounce over rapids in several inflatables that each hold six people plus a river guide. Overnight excursions that involve packing food, clothes, tents, and gear, are my favorite. River guides are usually inventive chefs who love to cook huge meals over campfires and know how to leave no trace of our existence when we depart a site. Once, when we were floating in three rafts along a quiet section of the Rio Grande just above the bridge at Embudo Station, a man and his wife who were not with our group capsized their canoe in front of us. We paddled hard to reach them, pulled them onto our rafts, and brought them to shore. The water seemed calm, but we watched their fiberglass canoe wrap around the center abutment of the bridge. It simply bent like a leaf and stayed there from the force of hundreds of pounds of water pushing against it. John McPhee describes how, “It was not speed but weight that we were experiencing: the great, almost imponderable weight of water….”

<18> This year two tourists have drowned near Pilar, our put-in site along the river. The waters are high, from so much snowmelt. Last year, a river guide told me of discovering a body, floating facedown in a hidden eddy behind a rock along the river north of Taos. The person had been missing for several days.

<19> I want my students to experience being on the river, watching the land go by, because we have been working outdoors on site-specific locations beside the river, watching it flow. We are usually on relatively quiet stretches of water. It is not about shooting rapids, but rather about the feel of being with a moving fluid.

<20> River guides can teach us a lot about being in the present moment. In a raft on a river, one has no choice but to be in this moment because every bend in the winding course brings a new threat. It is reassuring to see how calm a guide remains as they try to make a decision about what direction to take around an obstacle in our path. Can you imagine an agitated guide in total panic, yelling out: ‘Oh shit! There’s a boulder in our way! What should we do?’ Somehow, through experience and a deep understanding of flowing water, they remain composed and calm, standing up in the bow to assess the situation and then, unruffled, giving the orders for us to paddle hard on our left. Usually, as if without effort, the raft goes in the correct direction and we are floating again, going with the flow.

And you learned to read the river

eager to run the dancing white.

- Rae Crossman, Canadian poet

<21> More adventurous rafters choose the rivers they run for the extreme sport aspect of flying through rapids, dodging enormous boulders, and coming out alive on the other end to tell the tall tale. In Rivergods, Exploring the World’s Great Wild Rivers, Richard Bangs and Christian Kallen choose turbulent, churning rivers around the world in New Guinea, Chile, Alaska, Zambia, Ethiopia, and other countries where it is an enormous task just getting to a put-in site and where shooting sequences of giant whitewater rapids is the name of the game. Kallen writes that there are few rivers left in the world that are not “under siege, be it by diversion projects for irrigation, dams for hydroelectric power, or unthinking pollution.” He warns not to look elsewhere for villains, but that within each of us is the creator and destroyer. “It is a choice offered repeatedly wherever we go, every time we labor or travel, on every river trip we make.”

<22> Ferrying . One of the primary symbols of Venice, Italy is the gondola. Steered by one person with a single oar, their design is asymmetric. The left side is larger than the right by twenty-four centimeters and the bottom is flat. Eight different woods are used in the construction, which requires about 280 pieces. Today these colorful vessels ferry tourists through the elaborate, labyrinthian canal system. It is a competitive business for the gondoliers who rely on passenger fees for their income.

<23> Viewed from above, a simple canoe is shaped like a mandorla, derived from Italian for ‘almond,’ the form created in the center of two intersecting circles. It is a vaginal contour, and the outline of an eye. This was the shape the Vikings made using upright stones to mark burial sites on land, and they used the same word for boat, cradle, and coffin. Babylonians called the crescent moon a ‘boat of light.’ Mythological spirit boats bore the souls of the departed to other worlds, and carried the sun on its voyage through the underground of the night. The idea of voyage is implicit in the form of the boat. Sea, river, and lake voyages are often portrayed as allegories of a journey through life – or a crossing from the realm of the living to that of the dead. To the ancient Greeks, the underground River Styx in Hades bubbled with fire. If you had been properly buried with a coin under your tongue, this fee was presented to Charon, the silent ferryman of the river Styx, paid your safe passage to the next world. If you were not buried with a coin, you were doomed to wander along the shore of the river until the pauper’s entrance to Hades was found.

<24> Exemplary of boats’ role in the after life, an entire fleet was found in 1987. An archaeological team, led by David O’Connor, unearthed fourteen ancient boats, some as long as seventy-five feet, from a large complex burial center that was being excavated at the ancient Egyptian site of Abydos along the Nile, 260 miles from Cairo. Originally fully functional, these boats were buried, each in its own brick-lined tomb near the king, to be used in the afterlife. During his reign, the king could travel up and down the Nile in these boats as a display of wealth and military prowess, so he was certain to need them after death, in his next life. Neither reed nor dugout, these 5,000-year old planked boats are the oldest examples ever found of this type of construction.

<25> Boats are often used not just for symbolic escape, but also for actual fleeing from situations in a country where people would rather not remain. During the Vietnam War, the term ‘boat people’ was synonymous with political refugees. In recent times, Chinese, Haitian, and Cuban exiles have struggled to reach American soil aboard all types of floating craft. Several Cubans even tried to make an old car seaworthy, and managed to get close to Florida before it sank. In Volume One, A Gathering of Waters, I described watching a person swim across the Río Grande from the Mexican side to the United States side of the border at Laredo, Texas in an inner tube. At that section of the river, a small inflatable was the simplest vessel of choice.

<26> Spirit Boats . Wiley Chapman was the father of my Canadian friend Toby MacLennan. When he was on his deathbed, suffering from cancer and a brain tumor, he believed he had very little time left to live. A former engineer, Chapman mustered the strength to design a sailboat. Although he did not get to complete the building of the boat, Chapman grew increasingly healthy as he worked on the design and lived for three more years. Toby was familiar with the Egyptian belief about priests who chased the wandering souls of the sick in specially built “solar” boats and equated this myth with her father’s will to live. A photograph of the small model of the boat that Toby and her sister-in-law, Ellen, built for Wiley’s grave (with sails made from his pillowcase), was one of twenty-three works by artists included in a 1993 boat exhibition I curated for Santa Fe’s Charlotte Jackson Gallery. As I began to put together the exhibition, I found artistic interpretations of vessels everywhere. In her review of the show, art critic, Diane Armitage wrote, “What they inspired was more like a series of poetic cerebral voyages, begun at a point where form met function. And these voyages of the mind were triggered by Irland’s introductory displays filled with images of types of boats from her personal archive that explore the visual range of watercraft found the world over. There was a boat for nearly every occasion or cultural persuasion. Irland included examples of cutters, junks, barques, rafts, dinghies, gondolas and dugouts, battleships, ships in bottles, barges, and Siberian rock images of boats that look like jaw bones. Not to mention your basic yawl, sloop, ketch, brig or canoe.” At the time of the show Armitage had been reading Moby Dick, and so she arrived at the exhibition “steeped in the watery world of ships, quarterdecks, rigging, and mainmasts, … stems and sterns, and thus came prepared for this fantastic universe of boats curated for our dry-locked, ever-thirsty, sand-impacted selves.”

<27> Canoe Community . Whereas we in the desert are often in need of moisture, the Northwestern U.S. is usually inundated with it. In The Great Canoes, Reviving a Northwest Coast Tradition, David Neel describes the canoe as a metaphor for community, because everyone must work together on a journey. Crews paddling side by side over miles of water acquire respect for each other. During the canoe culture renaissance in the 1980s, First Nations residing close to the sea hosted one another on long canoe trips. Neel writes that the contemporary canoe has “evolved into an important political tool,” reinforcing the “existence and continuation of First Nation peoples and cultures in a social/political landscape that has endeavored to make us invisible.” Imagine the impact of twenty giant canoes arriving in a coastal harbor today.

<28> The Northwest Coast Indian canoe carver had an enormous responsibility during the two-year task; people’s lives would be at stake if the boat capsized due to faulty craftsmanship. The sculptor began with prayer, fasting and a sweat lodge. Then the cedar tree was selected, hand cut, and thanked for its sacrifice. Neel explains that the carver would abstain from sex, and leave hair uncombed to avoid cracks developing in the boat.

<29> Although the word ‘canoe’ originated from the word kenu (Native North American for dugout), another type of North American canoe is constructed of birch bark. The lightweight and waterproof bark of the birch tree is placed over a wooden frame. Canadian explorers and fur traders used large ones that carried a crew of up to twelve people plus a heavy cargo. In 1750, the French established the first canoe factory at Trois-Rivieres, Quebec.

When I must leave the great river

O bury me close to its wave

And let my canoe and paddle

Be the only mark over my grave.

- Frank Oliver Call, Canadian poet

<30> Paddles are just as elegant in form as the canoe – long, sleek, and sculpted to function in water. It becomes an extension of the puller’s body, enabling one to endure long hours on the water. Often they are painted or carved. The Squamish, Comox, and Haida Nations paint elaborate red and black designs of birds and animals on their canoe paddles. A kayak paddle has a blade at either end, while canoeists use a paddle with a single blade.

<31> In the Pacific Northwest of America and Canada, two primary types of boats are created -- one from the forest and another from the sea. As described above, the trees of the forest provide the necessary materials for the dugout, which is made from a huge carved-out log, leaving only what is necessary for keeping occupants afloat.

<32> The baidarka, a kayak traditionally made of skins stretched over wood frames and used by Alaskan coastal natives and Aleuts, is from the ocean. The sea lion or seal-skin boat begins to take shape as pieces of driftwood and whalebone are fashioned together to form the bare minimum of a vessel. In North Alaska Chronicle, Notes from the End of Time, John Martin Campbell reproduced the sketchbook of Paneak, a Nunamiut man, born in Alaska in 1900. One of the drawings illustrates how to build an umiak from carefully selected driftwood, covered with sealskins and transported by dogsled. Another ancient skin boat (discussed in Volume One) is the coracle, round like a shield, sometimes made from flannel and tar. Alternately, animal skins were used and waterproofed with oil or fat, but they needed to be dried out every few days or the skin would rot.

<33> Due to the skin’s propensity to rot, and the current status of environmentally endangered species, George Dyson, renowned boat builder, describes in Baidarka, The Kayak, how he uses today’s technology, thirteen-ounce polyester and lightweight aluminum tubing, to create baidarkas at his studio in Bellingham, Washington. Due to the long distances he travels by sea, Dyson has added sails to some of these vessels to rest his arms from paddling. While camping at night, he removes the fan-shaped sail from his boat and converts it into a teepee-like tent on shore.

<34> Birds and bees . While high-tech instrument panels assist most vessels across vast expanses of open-ocean, a few tiny pockets of sea-faring cultures sometimes still navigate primarily without technology from island to island on masterfully handcrafted outriggers with elegant sweeping sails. In his autobiographical account, The Last Navigator, Steven Thomas describes how Micronesian elders, with dolphin tattoos on their legs, possessed the knowledge to find their way over the sea, using only natural signs – stars, birds, and ocean swells. Since noddies and terns fly direct paths each day at dawn and dusk to fish for food, a navigator could watch the flight patterns of these birds to assist the final approach toward land. The islanders used to navigate at night, missing coral reefs and islets by aligning their boat with specific stars. As teaching aids for younger generations, they created star charts from reeds and coconut fronds to illustrate positions of islands, the rising and settings of stars, and the directions of the swells. Today, even amongst remote island cultures, the magnetic compass has mostly replaced steering by the stars.

<35> The Micronesians are not the only “seafarers” who rely on nature’s directions. In Pablo Neruda, Absence and Presence, Luis Poirot wandered around the abandoned home of the poet at Isla Negra, Chile, where the windowsill still held clear glass bottles filled with tiny ships. Neruda once described the building process as if small carpenters had flown in on the backs of bees with their miniscule hammers, ropes, nails, and planks, to construct these boats that will never float. The Chilean poet wrote that he needed the sea because it was his teacher, and, “The fact is that until I fall asleep, in some magnetic way I move in the university of the waves.”

Liquid Ether

Liquid Ether furthers our relationship with water by relating the ‘prima materia’ with the vastness and gravitational pull of the celestial realm…. All the salt boats hang suspended in a unifying ethereal space, rooted in the earth. This work is like a many-celled organism that appears to defy gravity and feed on air, yet is grounded in a love of materials and respect for rigorous research.

- Diane Armitage, artist and critic

Liquid Ether. 1992. 11’ high, dimensions variable. Salt encrusted bamboo and suspended boats, welded steel bases, electric lights.

Vessel I

This ancient form of floating vessel implies journeying, usually into the unknown…. Nonfunctional, it becomes a spirit boat or carrier for the soul. Many of Irland’s boats are line drawings in space. To traverse the waters in boats becomes a journey of the heart.

- Harmony Hammond, artist, writer

Vessel I.1985. Bent willow, waxed cord. 14’.

Navigating the Current

Navigating the Current . 1989. Soldered copper, earth, matte medium, moss, wood, Plexiglas drawn with pre-Keplarian maps of the moon’s pull on the tides. 17” x 30” x 4”.

Basia’s Boat Forms carry intimations of travel, of constellations, of growing and rebirth (blooming).

- Tony Urquhart, Canadian artist

Catamaran 1984. Bent willow. 18’

Boats usually connect two pieces of land separated by water, but in Irland’s sculpture they link the elements of water and earth with the spiritual essence of sky.

- Jason Silverman, Canadian writer

Salt Boat I.1995. Welded copper and salt. 6 1/2’

Salt Boat II. 1995. Welded black wire, matte medium, rock salt. 2 1/2’

Boat board. Detail.

Art barge, 2005, Cincinnati, Ohio.