Reconstruction 6.3 (Summer 2006)

Return to Contents»

The Social Nature of Natural Resources - the Case of Water / Jamie Linton

Abstract: Of all things, water is among the most difficult to pin down. It is nevertheless characteristic of modernity that we ascribe to it an essence, on which basis particular kinds of human-water relations are made possible while others are denied. The ascription of an essential identity to water constitutes a social and political act by which it is both made known to people and made available for people. This paper explores the implications of ascribing to water an identity as "resource." Water was pronounced a resource in the United States early in the last century in the context of the conservation movement, the development of the hydrological sciences and growth of the state as an agent of water control. As a resource, water has been made available in ways that correspond to what historian Samuel P. Hays described (critically) as "the gospel of efficiency" and economist-geographer Erich Zimmermann put forward (uncritically) as the "functional approach". The political implications of this manner of disclosing and disposing of water are explored in terms of who may get it and for what purposes. Finally, the paper considers the possibility of disestablishing water's resource-identity, and the opening that this presents for a cultural politics of water.

Introduction

<1> Originally, there was nothing but water, and water was nothing but chaos. Christians are given to understand that God called this situation to order by gathering all the waters under heaven together in one place, and then (mercifully) letting the dry land appear in their midst. (Genesis 1-9) He saw that this was good, but that didn't prevent him from occasionally flooding the place in order to allow things to get started all over again on a more sound footing.

<2> I'm not a practicing Christian, but I subscribe fully to the view of water's original chaos. In a longstanding poststructural tradition, I would say however that God is dead, and that it must therefore be we, us, (ourselves) who give to water its form and its identity. Whether as a compound of hydrogen and oxygen, as the stuff that flows through the hydrologic cycle, as that of which we humans require eight glasses daily, or as lifeblood of the environment, water is some-thing that comes to life, acquires meaning and assumes utility through its interactions with people.[1] Like the rest of nature (including human nature!), water can't help but be saturated with human meaning and intent.[2] The genealogy of water always describes a history of social production.

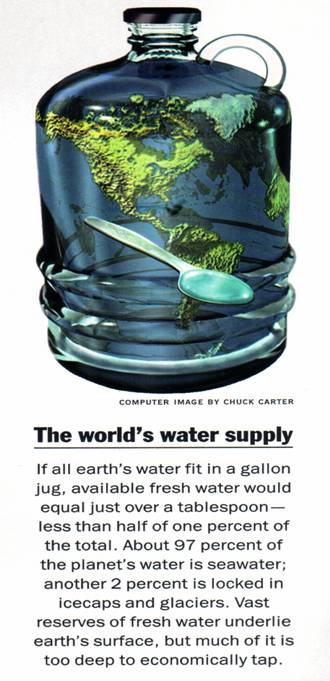

<3> In this paper, I want to explore one of the more powerful of water's myriad modern identities. That water is understood and represented as a natural "resource" is so commonplace that we hardly notice it. (see Figure 1) This invisibility gives water great power and stability as a resource – indeed we might say that it makes water a natural resource. The naturalness of water's resourcefulness authorizes certain hydrosocial relations and uses while denying others and forbidding the realization of other meanings and potentialities inherent in water's original blue chaos. As the ecofeminist writer and activist Vandana Shiva has written, naming something a "resource" is one of the most common discursive moves by which "nature has been clearly stripped of her creative power; she has turned into a container for raw materials waiting to be transformed into inputs for commodity production." (Shiva 1992:206) Surely the identification of water as a natural resource is one of the more hubristic performances of which modern man (and I do mean man) has shown himself capable of executing.

<4> At the end of the paper, we will return to the question of challenging the resourcefulness of water so as to help legitimize alternate hydrosocial relations. In the meantime, we will dive into a stream of words and ideas that have cut a deep channel through which so much of modern water has flowed. This stream can be traced to a source located approximately in early twentieth-century (North) America.

I – Making Water Known as a Resource

<5> I want to begin by quoting a paper published in 1909 by W.J. McGee, a leading light of the early conservation movement and Theodore Roosevelt's main confidante and spokesperson for matters pertaining to exploitation and management of the nation's waters. [3] Here McGee represents the cutting edge of progressive American thought about the correct way to dispose of the nation's water.[4] The title of the paper is "Water as a Resource".

No more significant advance has been made in our history than that of the last year or two in which our waters have come to be considered as a resource – one definitely limited in quantity, yet susceptible of conservation and of increased beneficence through wise utilization. The conquest of nature, which began with progressive control of the soil and its products and passed to the minerals, is now extending to the waters on, above and beneath the surface. The conquest will not be complete until these waters are brought under complete control. (McGee 1909:522-523)

<6> Why is McGee making this statement now? After all, water had been used extensively for purposes of navigation, irrigation, and power for thousands of years. McGee knew this. He was aware that prehistoric peoples of North American had constructed "elaborate systems of irrigation" upon which complex agricultural societies had been built (McGee 1895:372-3) and no doubt he knew of the great ancient hydraulic societies of Mesopotamia, China, India, and Egypt. In his own country, water had powered the American industrial revolution in the East. The Erie Canal had been constructed some seven decades earlier, providing a transportation resource between the Hudson and Great Lakes-St. Lawrence drainage basins. The Bureau of Reclamation had been established 7 years earlier, had completed or initiated dozens of projects (including the construction of numerous large dams west of the Mississippi) by the time McGee wrote. Water from California's streams had been forced through hoses at high pressure in order to wrench placer gold from the earth in the mid-nineteenth century. So why is water suddenly a resource in 1909?

<7> No doubt, the relatively recent advent of hydroelectric power contributed to this "advance". Improvements in the design of turbines and the invention of the dynamo and alternating current in the latter part of the 19 th century had made it possible for people to recognize a new kind of resourcefulness in water by the early 20 th century. Hydro-electricity was seen as one of the hallmarks of a new era, one that Lewis Mumford would later (and famously) describe as "the neo-technic revolution". (1934) There was tremendous excitement as "the mysticism of hydro development" gripped an entire continent and the prospects of exploiting hydro-electrical potential on a large scale, fired the imagination of politicians, industrialists and engineers alike. (Nelles 1974:215-275) This potential was uppermost in the minds of McGee and his colleagues in the conservation movement. (McGee 1911; Leighton 1909; Newell 1920) Nevertheless, water had been famous for generating power (albeit in direct form) for at least a thousand years. (Smith 1975) The growth of hydro-electricity alone, therefore, is unlikely to account for this newfound recognition of "water as a resource."

<8> The deliberate naming of water as a resource, I think, needs to be seen in the context of scientific, economic and political circumstances that comprise the conservation movement in the United States during the first two decades of the 20 th century. In essence, it was at this time and in this context that water became known to the state in a way that made it an object of calculation and subject to a particular kind of accounting and manipulation, which for McGee and his contemporaries was both reflected and produced by declaring water a "resource." Many accounts of the conservation movement stress its democratic ideal – often expressed as a "crusade" - of serving the interests of the "people" over the interests of the corporations, its "trust-busting" rhetoric, its tempering of the doctrine of laissez-faire etc. However Samuel P. Hays has argued persuasively that the populist rhetoric of the movement belied its main significance. "Conservation, above all," he argues, "was a scientific movement, and its role in history arises from the implications of science and technology in modern society… The essence [of the movement] was rational planning to promote efficient development and use of all natural resources." (Hays 1959:2) Rather than the question of "resource ownership", Hays stresses, the conservation movement was mainly concerned with promoting a rational, efficient regime of "resource use." (1959:262) At its heart was the scientific, technocratic vision of a society cleansed of the sin of waste, motivated by – to use Hays' term - "the gospel of efficiency."

<9> McGee and others argued that the conservation of water – which meant " putting rivers, and eventually their entire watersheds, to work in the most efficient way possible for the purpose of maximizing production and wealth" (Worster 1985:155) - could only be advanced through the apparatus of the state. For one thing, around the turn of the century it was recognized that the development of streams and rivers in the American West could no longer proceed on the basis of private enterprise alone. "[T]he West", as environmental historian Donald Worster has put it, "had gone as far as it could on its own hook." (1985:130) The increasing size and growing costs of water projects and the complexities involved in exploiting navigable waters crossing state boundaries meant that the federal government had to step in. It did so in 1902 with an act to establish the Bureau of Reclamation, an act described by Worster as "the most important single piece of legislation in the history of the West." (1985:130)

<10> But state intervention in the management and control of water also stemmed from the nature of the stuff itself. Water differs from other natural resources like soils and trees and minerals in several respects. First, it is constitutionally on the move, a factor that makes it more difficult to account for than resources of a more fixed address. Second in many parts of the continent, it can be extremely irregular in a temporal sense, with quantities of precipitation and streamflow varying enormously from season to season and from year to year. Third – and although this applies to all resources, it is particularly the case with water - it may be applied to many different potential uses, which are themselves a function of different cultural and technological circumstances.[5] Water can be used to generate hydro-electricity, float ships, irrigate crops, lubricate cities, grow fish, supply a vital raw material for industry… The early conservationists were cognizant of all these qualities of water, and of the fact that dealing with them in a rational manner implied the need for central planning, coordination and control. The latter distinction was particularly important: The early conservationists elaborated the idea that water is "a single resource with many potential uses." (Hays 1959:6) Determining which of these uses water should be applied to - what proportion should be allocated for this purpose and what proportion for another, how water could be managed so as to promote the greatest overall benefit to society - was what "conserving" the resource was all about.[6] All of these factors – water's mobility, its variability and the multiplicity of its potential uses – meant that in order to exploit it fully, to conserve it, water had to be brought to heel. In McGee's words, water had to be "brought under complete control" in both an epistemological and a material sense. And the only agency capable of such a gargantuan feat was the state.

<11> It was thus that in the early 20 th century the state became "an agency for conquest" with respect to water in the United States. (Worster 1985:130) Such ambition was reflected in the motto of the Bureau of Reclamation, one that captures perfectly the essence of the conservationists' view of how water should be disposed of: "Total Use for Greater Wealth." (1985:266) Realizing such a conquest demanded the capacity to survey the national field, to account for the stocks and flows of available water, and to represent this accounting in a way that was conducive to rational, scientific management. James C. Scott uses the term "legibility" to describe the means and apparatus by which the state has been able to take hand of a vastly complex field and reduce it to a framework and to terms that are actionable by government agencies so as to bring things under control.

Certain forms of knowledge and control require a narrowing of vision. The great advantage of such tunnel vision is that it brings into sharp focus certain limited aspects of an otherwise far more complex and unwieldy reality. This very simplification, in turn, makes the phenomenon at the center of the field of vision more legible and hence more susceptible to careful measurement and calculation. Combined with similar observations, an overall, aggregate, synoptic view of a selective reality is achieved, making possible a high degree of schematic knowledge, control and manipulation. (Scott 1998:11)

Scott describes how thoroughly the environment has been refashioned by what he calls "state maps of legibility" – models of nature that "rather like abridged maps…represented only that slice of [reality] that interested the official observer." (Scott 1998:4) In Scott's terms, in order for water to be conserved, used most efficiently, brought under control – indeed, in order for it to be recognized as a resource – it had to be made "legible". What was required was a means of knowing "precisely how much water was running through the land." (Worster 1985:135)

<12> Returning to the question of why now - in the first decade of the 20th century - water is officially pronounced "a resource," the significance of the development of (state-sponsored) hydrologic sciences becomes apparent. For it was just at this time that agencies like the United States Geological Survey (USGS) were providing the statistical means by which water might be grasped, measured, accounted for, represented quantitatively - and thus be managed scientifically. In 1888, Congress had authorized the USGS to undertake the first investigation of water in the West. Frederick H. Newell[7] was put in charge of a massive program of measuring streamflow, locating reservoirs and canals, and – by the 1890s – studying groundwater flows and relations between phases of what is now called the hydrologic cycle. This marked the beginning of the Hydrographic Branch of the Geological Survey and rapidly evolved into a nation-wide program for the scientific accounting of the country's water. (Hays 1959:6) "The information thus obtained and widely diffused", Newell wrote subsequently, "laid the foundations for a presentation of the needs and opportunities of water conservation and furnished the facts for action by Congress…"(Newell 1920:149) In other words, on the basis of the hydrological data gathered, government agencies – particularly the Bureau of Reclamation – were able to plan and execute water development projects. By 1911, McGee thought it reasonable and expedient to declare:

Under the federal legislation and administrative operations, water is not only measured more accurately than in any other country but is steadily passing under control in the public interest… The advance in this direction during the last decade has been especially rapid; and though apparently little noted, it is among the most significant in our entire history with respect to knowledge, use and administration of the natural waters. (McGee 1911:822)

<13> The project of accounting for the nation's water supplies was reflected in developments in academia. In 1904 the first course on hydrology was taught at an American university and the first American hydrology "textbook" was produced the same year. (Reuss 2001:275) In the first decade of the 20 th century, water was becoming systematically known in a quantitative sense in the United States, driven by the emerging science of hydrology and by the growing demands of the state for reliable hydrographic data. Like the resources of the land – mainly forests, soils and crops – water was now becoming legible to central planners and development agencies in a way that enabled them to exploit its resourcefulness. Once again representing the emerging scientific view of things, McGee captured this moment in the instant of proclaiming water as a resource:

Our growth in knowledge of that definite character called science is notable – particularly in its ever-multiplying applications… It is in harmony with the general development that the quantitative method is now applied not only to soil production in forests and crops, and to mine production and minerals in the ground, but finally to the rains and rivers which render the land habitable and the ground waters which render it fruitful." (McGee 1909:38)

This marks something of a radical change in the way water is to be understood. "The quantitative view of water, except in smaller measures is", McGee points out, "so new to thought that familiar units are lacking." (McGee 1909:523) It was to become one of the primary preoccupations of the USGS and other relevant federal agencies to standardize hydrologic methods, instruments and measures while expanding the scope of investigation to encompass the entire cycle from precipitation to infiltration, groundwater flow, runoff, streamflow and evaporation. (Langbein and Hoyt 1959)

<14> This "quantitative view of water" provides a way of knowing and representing the water-chaos that literally makes water available for exploitation. Through the scientific (hydrological) practice of measuring and representing stocks and flows of water in the hydrosphere, water is transformed into an abstraction that is perfectly, and quite naturally, suited for human use. (Figure 1) Martin Heidegger is one thinker who has tried to get to the bottom of the question of how the world has come to be present to us moderns as a collection of objects of calculation and exploitation. (Heidegger 1977; Braun 2002:15) The quantification of things rendered in modern scientific practice, he argues, is a mode of disclosure that disposes nature to yielding benefits to humanity. "Modern science's way of representing", he points out, "pursues and entraps nature as a calculable coherence." (Heidegger 1977:21) The historical significance of methodically quantifying water in hydrologic practice is thus suggested.

<15> Representing the "stock of water" suggests another important explanation of how and why it has become a "resource"; because water now has a definite "supply", it is recognized as having a definite limit. Water, in other words, is susceptible to general scarcity. Prior to being understood as a resource, water "has been viewed vaguely as a prime necessity, yet merely as a natural incident or providential blessing. In its assumed plentitude the idea of quantity has seldom arisen…" (McGee 1909:532) So long as we can assume its "plentitude" and regard it as a "natural incident or providential blessing", the general sense of water scarcity can hardly arise. But now, McGee echoes the national dread of waste by noting "our growth in population and industries is seriously retarded by dearth and misuse of water." (1909:532) Because water is capable of scarcity, it must be conserved, used wisely, and never wasted; it must be "considered as a resource – one definitely limited in quantity, yet susceptible of conservation and of increased beneficence through wise utilization." (1909:522-523)

<16> Scarcity is an economic concept, produced in economic discourse rather than in nature. Postulated as a general condition in classical and neo-classical economics, it provides a rationale for the market as the means of allocating (scarce) resources efficiently and productively. (Xenos 1989: Ch.3) Scarcity and modern economics are therefore joined at the hip. The presupposition of scarcity as the natural condition of water resources is implied in F.H. Newell's prescription for "Hydro-Economics": a formulation that "is perhaps most suitable in that the prefix conveys the idea of water and is followed by the conception of its efficient employment, of utility or of thrift." (Newell 1920:31) In the context of the progressive conservation movement, however, the economics of water meant state intervention; the survival of capitalism could only be ensured by tempering the inclination of capitalists to destroy their own resource base. Thus Newell's hydro-economic presumption that "the great natural resources such as mineral wealth and water power are a public trust to be administered for the greater good to the greatest number… " (1920:30) For McGee, also, the now-apparent "dearth" of water means the need for government to apply "the righteous principles of the greatest good for the greatest number for the longest time." (McGee 1911:825) The conservationists' constitutional scarcity of water resources thus authorized a program of state intervention in the nation's waterways, a program that would, as McGee put it, "not be complete until these waters are brought under complete control." (McGee 1909:522-523)

<17> What were the political ramifications of this manner of identifying, accounting, disclosing and disposing of water? One of the significant effects of pronouncing water a resource was to remove it from the broader political sphere and reduce its relations with people to a matter of technical efficiency. "Since resource matters were basically technical in nature, conservationists argued, technicians, rather than legislatures, should deal with them." (Hays: 1959:2) The exclusive application of instrumental reason is applied without question to that which is deemed resourceful. This is an extremely important point, and one to which we will return below. Water – as with all resources - presents numerous problems of a political nature. Questions such as who should have access to it, whether it can be ‘owned', in what manner is it to be used or left unused and for whose benefit, etc. – these are political questions that raise the potential of political conflict. A broader politics of water contends over the question of what water is. If water is a sacred substance, a gift from God, a human right, lifeblood of the environment, it is likely to be respected and treated in a manner quite different from its treatment as raw material, a commodity, or a resource.

<18> The point here is to stress what was at stake in naming water as a resource, and the contention is that this brought water within the discourse of - made water subject to - the ‘gospel of efficiency' such that its disposition was rendered a technical rather than a political problem. That this in itself concealed a kind of political agenda, described by Hays in terms of "the political implications of applied science", is something that I want to consider below. Conservationists regarded partisan politics, political compromise and jurisprudence as inappropriate modes for deciding how problems involving resources should be resolved. The jockeying for advantage, the need to compromise, the apparent irrationality of partisan motives, all led conservationists to fear that in political discourse "concern for efficiency would disappear. Conservationists envisaged…a political system guided by the ideal of efficiency and dominated by the technicians who could best determine how to achieve it." (Hays 1959:3)

<19> As we shall see, with the elaboration of the functional theory of resources in the 1930s, the essential reduction of nature so as to render it subject to expert control and management was retained from the conservation era, with the difference that the need for central authority became an implied corollary of nature's resourcefulness rather than a matter of express moral conviction. In both cases, the matter of what to do with water became a matter of allocating it to its most productive use, or combination of uses, in accordance with the principle of extracting the greatest possible economic benefit. The contemporary economic, scientific and technological circumstances allowed McGee to formulate a rational, prioritized prescription for the disposition of the nation's water resources:

In considering the benefits to be derived from the 215,000,000,000,000 cubic feet of water annually received, the paramount use should be that of water supply; next should follow navigation in humid regions and irrigation in arid regions. The utilization of power from the navigable and source streams should be kept subordinate to the primary and secondary uses of the waters; though other things equal, power development should be encouraged, not only to reduce the drain on other resources, but because properly designed reservoirs and power plants retard the run-off and so aid in the control of the streams for navigation and other uses. (McGee 1909:48)

Here we have a hierarchy of uses to which water is to be applied: first, for industrial and urban development; second, for purposes of navigation in the East and irrigation in the West; and third, for generating hydropower. This might be considered a prototype, the first of many hierarchical formulations for the correct allocation of the nation's supply water resources – bearing in mind that these have changed as different socio-economic circumstances, technologies and cultural priorities have prevailed.[8] Today, the term used most often by state agencies to describe the prioritized modes of exploiting water is "beneficial uses." Every itemization and prioritization of the beneficial uses of water is significant for its omissions. It is worth considering briefly what is left out in the particular scheme represented by McGee. Of course, relations with, and uses of, water practiced by contemporary Native North American peoples is left entirely out of the picture; the indigenous economies and cultures that were still partly sustained by salmon fishing on west coast rivers, for example, hardly fit into this hierarchy of uses. Generally absent is any consideration of the ecological value and function of water, such as in-stream uses to support basic aquatic ecosystem functions. Likewise, amidst the contemporary mania for industrial development, recreational or aesthetic values and uses of water are also completely missing.[9] All in all, there is no place for Native Americans, fish (or people dependent on them), bathers, tourists, or benthic invertebrates in this scheme. Nor is there the slightest regard paid to the hydrosocial relations and the rights of people whose lives and livelihoods must necessarily be disrupted by the building of dams, flooding of reservoirs and diversion of streams required to maximize "the benefits to be derived from the 215,000,000,000,000 cubic feet of water annually received."

<20> To sum up so far, water becomes a resource in the United States in the first decade of the 20 th century because of a number of changes in social circumstances – technological, scientific, economic and political. These changes allowed water to be appraised – made legible – by the state as a resource of a certain quantity that is to be disposed of in the most rational, efficient manner possible. The early conservationists' hopes for the state domination of water were not to be realized until several decades later. Due to a combination of agency rivalry in Washington, political bickering and outright hostility to conservationist policies in Congress, the early movement was stymied in its efforts to effect major policy change. With some notable exceptions[10], a backlash against conservationism during the years of Republican control of the White House from 1921 to 1933 held projects like multi-purpose river basin planning and development in check. (Rogers 1996:50) It was not until the New Deal era that they were put into effect, realizing McGee's vision of "complete control" of the nation's waters in several of the country's largest river systems. We shall return to these waters presently. But first, a tributary digression through the work of a German-American economist and geographer named Erich E. Zimmermann is in order.

II – The Functional Approach to Resources (a slight diversion)

<21> In 1933, the first edition of Erich E. Zimmermann's book, World Resources and Industries , was published. (Zimmermann 1933)[11] Zimmermann is well known as author of the "functional approach", which remains the dominant theory of natural resources held by many economists and resource geographers.[12] The major significance of this approach for our purposes is that it provides a solid theoretical foundation for the technocratic mode of appraising and disposing of resources that was put forward in nascent form by the early conservationists. With respect to water, Zimmermann in effect takes up from where McGee and his colleagues left off, giving the discourse of water's resourcefulness and all it implies a powerful theoretical grounding.

<22> Zimmermann was no crusading conservationist in the populist tradition.[13] He rather took it for granted that central planning was a necessary and expedient means of ensuring that resources be exploited in a rational manner. (Zimmermann 1951:4-6) But in the most important respect, his functional approach advanced the legacy of the Roosevelt-era conservationists: Its overall purpose was to provide a schema for appraising and managing resources that rendered the matter a technical problem rather than a political one. He put forward the functional approach as a new – a "scientific" – way of thinking about resources. "It follows that the concept of resources, because it is so new, remains to be developed scientifically." (1951:6) This development nicely avoided the problem of having to consider resources a political problem. Writing in the concluding part of his 1933 tome, Zimmermann admits, "Little attention has been given in this book to the political aspects of resource ownership and utilization." (1933:802) Instead these have been supplanted by the application of technique. The functional approach orders the world of nature and the world of society in a manner that determines a particular set of relations between the two. "To bring order into the almost chaotic mass of dynamic forces into which, as a result of the increased complexity of social and other relations, the process of resource appraisal has developed, the major factors must be isolated and analyzed separately." (1933:10) Thus "ordered", "isolated and analyzed", the question of resource appraisal and exploitation is made regular and manageable. Despite its promise of avoiding politics, I want to point out that this order constitutes a definite political agenda by foreclosing an enormous range of options for alternative modes of appraisal and use of those aspects of the world deemed resourceful.

<23> Zimmermann's functional approach holds that nature is meaningless – in his terms, it is merely "neutral stuff" - until people identify particular aspects or elements of it that can be used. (Zimmermann1951: Ch. 1) Neutral stuff becomes "resources" when cultural and technological circumstances permit it to be appraised as such. "In other words, the word ‘resource' is an expression of appraisal and, hence, a purely subjective concept." (1933:3) Thus a "recurring theme" (Hanink 2000:227) in Zimmermann, and one that has endured in the way many of us think and talk about resources: resources are not pre-given but are evaluated and constituted within specific historical, technological and cultural contexts. "For each civilization rests on a different basis of resources, taps a different combination of environmental aspects." (1933:4) A resource to one group of people may be merely "neutral stuff" to another group, or to the same group in a different set of circumstances. Hence the often-cited statement by Zimmermann that "resources are not; they become." (1951:15)

The word "resource" does not refer to a thing nor a substance but to a function which a thing or a substance may perform or to an operation in which it may take part, namely, the function or operation of attaining a given end such as satisfying a want. In other words, the word "resource" is an abstraction reflecting human appraisal and relating to a function or operation. As such, it is akin to such words as food, property, or capital, but much wider in its sweep than any one of these." (Zimmermann 1951:7)

<24> Somewhat ironically (given what I am about to argue below) Zimmermann's functional approach is sometimes noted for its consistency with the "cultural turn" in the social sciences, which became pronounced in my home discipline of geography in the 1990s.[14] The general shift in attention to the cultural dimensions of social, economic and political processes appears to mesh well with a view of resources as expressions of human appraisal that vary within different historical and cultural contexts. Zimmermann is sometimes even included among the thinkers who have given rise to the cultural specification of nature. (cf Meredith 1995:362).

<25> In the sense that it recognizes the cultural specificity of how and why resources become what they are, there is a certain congruity between Zimmermann's functional approach and the idea of social nature to which this essay is generally directed. Although he did not use the term, Zimmermann might have said that resources are social constructions. What I am concerned with here, however, is the problem of how resources become what they are. As "a purely subjective concept" (1933:3) the resource-idea admits of the potential for diverse constructions of nature; however, it raises the problem of which - or whose – particular construction counts in the event of the same thing (the same bit of ‘neutral stuff', as it were) being appraised in more than one way. In the case of a river, for example, is it to be disclosed as a means of navigation, a recreational resource, a source of power, a home for fish and wildlife, an object of contemplation, a means of supplying the essential ingredient for irrigation agriculture, a corridor of commerce, a raw material for industrial development, an attraction for tourists, a metaphor for the identity of a people…? Having raised this problem by defining resources as expressions of social appraisal, it was necessary for Zimmermann to establish some means for determining the particular sort of appraisal from which all matters pertaining to the exploitation of the resource would flow. Politics, of course, would be allowed to have nothing to do with it. As with the conservationists, every aspect of the appraisal, disposition and management of resources must be reduced to an expert discourse – one that would produce the most rational, efficient outcome.

<26> Zimmermann's solution was to construct a narrative describing a spiral along which society ascends through time, with each successive moment occurring on a higher cultural plain than the last, and thus rendering all previous moments obsolete. The narrative of progress, in other words, accounts for the historical differences in resource appraisal, and determines that the resources at any given time are those that correspond to the most advanced, or developed, state of society.[15] The story begins with a creation myth, a distinction posited between a primitive "man on the animal level" and a more developed "MAN", the latter of which "arrived [at] a time, 50,000 or more years ago, when the genus Homo was singled out of all organic creatures to travel a road closed to all others – the road of active man-willed adaptation." (Zimmermann 1951:8) Zimmermann's animal ‘man' is "subject to the same laws of ecology and passive adaptation which bind all other animals… On this animal level man found nature niggardly indeed; he barely managed to survive…on resources which were limited by the scantiness of his own capacities." (1951:8) Advanced "MAN", on the other hand "learns to exercise the supreme human prerogative of active adaptation." With his "superior brain power" MAN has "gained control over many of the other creatures found on earth." Through cultural adaptation to his environment and with the development of society, MAN "emerges to transform the natural landscape." (1951:8,9)

<27> Zimmermann's depiction of MAN, culture and nature (Figure 2) is presented in what must, to any sensitive reader, appear rather startling terms: "The idea of showing culture as a spearhead which man drives deeper into the realm of nature, converting more and more ‘neutral stuff' into resources…is presented readily enough, as shown…" (Zimmermann 1951:12) The "spearhead", it should be emphasized, drives in one direction through history. Thus, in Zimmermann's terms, "emancipated" cultures succeed "primitive" ones in the appraisal of more and more "neutral stuff" as resources. "So long as the human race continues to climb upward to higher culture levels," Zimmermann asserts, "culture is bound to become increasingly important as the dynamic force in the creation of resources." (1951:15)

<28> The distinction between "man" and "MAN" is problematic enough. For one thing, it rests – ironically enough – on a radical distinction between culture and nature: "Man on the animal level constitutes part of nature. MAN on the human level represents the counterpart of nature. Nature is non-MAN… The sum total of changes wrought by MAN is here called culture." (Zimmermann 1951:8) Apart from this, the emergence of a distinct form of human being some 50,000 years ago fails to correspond with any understanding of biological or cultural evolution that this author is aware of. Nevertheless, it is upon this myth that Zimmermann rests his assertion that resources are a matter of cultural appraisal and not merely things present and pre-given:

To understand resources one must understand the relationship that exists between MAN and nature. For that purpose it is necessary to conceive of the human being as existing on two levels, the animal level and the supra-animal or human (or social) level…

The story of the rise of man from the animal to the human stage is of the utmost significance for the meaning and nature of MAN's resources as distinguished from the resources of animals. MAN's resources, to an overwhelming extent, are not natural resources… The majority of MAN's resources are the result of human ingenuity aided by slowly, patiently, painfully acquired knowledge and experience. (Zimmermann 1951:8,9)

The concept of resources requires a radical separation between culture and nature because without such a separation, resources cannot be understood in the abstract, subjective sense of the functional approach. Or to put this a slightly different way, it is important for Zimmermann that, in his terms, "resources" are something other than "natural resources", because otherwise, we are no different from animals.

<29> …Or savages. As already noted, Zimmermann's pre-resourceful nature is described as "neutral stuff", and for primitive, pre-cultural "man", it was the totality of his environment: "One can envisage him submerged in an ocean of ‘neutral stuff,' i.e. matter, energy, conditions, relationships, etc., of which he is unaware and which affect him neither favourably nor unfavourably." (Zimmermann 1951:8) It is the virtue of the more culturally advanced "MAN", dignified with intelligence and ingenuity, to convert "neutral stuff" into resources. The clear implication is that "primitive" people, with little "knowledge", "wisdom", "ingenuity" and "patience", are unable to appreciate nature as "we" do, i.e. as "resources." Thus, for example, the aboriginal peoples of North America and elsewhere had (and continue to have) pathetically little appreciation of the resource wealth that surrounded(s) them. Zimmermann quotes the economist Wesley C. Mitchell, noting that he "was absolutely correct when he wrote":

Incomparably greatest among human resources is knowledge. It is greatest because it is the mother of other resources. The aboriginal inhabitants of what is now the United States lived in a poverty-stricken environment. For them, no coal existed, no petroleum, no metals… There agriculture was so crude that they could use only tiny patches of soil… (quoted in Zimmermann 1951:9)

The cultural relativity of resources is a key tenet of the functional approach, and one that has helped ensure its longevity. However, because such relativity is seen in historical rather than contemporary terms, it presents no problem for Zimmermann. The idea of progress, that "the human race continues to climb upward to higher culture levels" (Zimmermann 1951:15) means that "MAN's resources" are continually being rendered from neutral stuff, and not from other peoples' resources. The ideology of progress dictates that what is seen as a more culturally sophisticated use of nature always trumps a less sophisticated use. This has two aspects: First, when something is recognized by "us" as a resource, it gets taken away from others who are not smart enough or sophisticated enough to recognize its value in the same way that "we" do. Thus the Great Plains was properly cleared of bison (and the people who depended on them) to make room for agriculture, and dams are built on rivers by people who see more value in electricity than fish.[16] Second, when something is recognized as a resource, it is understood – and the practice of resource management is meant to ensure - that it gets put to its most "economical" use.

<30> Zimmermann's approach dictates that once something is appraised as a resource it is disposed of in accordance with how it might "be used to yield the highest return" to private enterprise and to society. (Zimmermann 1951:16) Recall McGee's hierarchy of water uses: first water supply followed by navigation, irrigation and then power. The functional approach describes a systematic, "scientific" framework for institutionalizing such a hierarchy. Essentially, the various tasks involved in appraising, evaluating and exploiting resources are divided up between the physical and the social sciences, and organized in a sequence whose ultimate purpose is defined as "the promotion of real wealth." (1951:17)[17]

III - Back into the Water!

<31> Returning – at long last – to the water, Zimmermann devoted a chapter in World Resources and Industries to "The New Era of Water Power." (1933: 542-558; 1951:568-594) Between the time that McGee had placed water power rather low on his list of water uses in 1909 and Zimmermann first proclaimed the functional approach in 1933, improvements in the design of turbines had significantly increased the hydraulic head at which turbines could operate efficiently, greatly increasing the potential of hydro-generation. (McCully 1996:15) Vast improvements in the efficiency of long-distance transmission of electricity (through stepped-up voltage) was another factor making hydro-electricity – for which there is usually no choice but to transmit power over long distances - more economical. Increases in the cost of fuels in the 1920s also raised the price of hydro's competitors in thermal power generation. (Zimmermann 1951:570) These factors contributed to substantial growth in installed hydroelectric capacity during the 1920s in the U.S. and abroad, allowing Zimmermann to declare "the new era of water power" by the early 1930s.

<32> But it was developments of a political nature occurring in the mid-1930s – developments that sprang from the ideals of the earlier conservation movement - that were most decisive in revealing the new resourcefulness of water. In 1951 Zimmermann was able to reflect upon these developments in terms of "the revolutionary change in man's attitudes towards water power":

The most powerful blow struck in defense of water power has come from…changes in human attitudes, attitudes which imperceptibly emerge from the womb of social philosophy and take on tangible form in rewritten and reinterpreted laws and in revised public policies. In the United States these new attitudes with their tangible aftermath are largely identified with the New Deal. But that is not quite accurate. The roots of the new movement, the origin of the new way of viewing our natural and national endowment of basic assets, reach further back in time, to the conservationists of Theodore Roosevelt's day…

The crux of the new philosophy is the realization that, in the long run, the magnificent achievements made under private capitalistic enterprise are endangered by inadequate regard for the durable basic assets, natural and cultural, on which all economic life depends, and for the conditions, forces, and processes of nature which underlie all human endeavor…

In [this] scheme of things, water plays a vital part. If properly cared for, water is the bringer of life; if neglected, it can be the cause of disaster. And it has been neglected by the market-conscious leaders of our economy…(Zimmermann 1951:571-572)

Given this neglect, the central role of the state in developing water resources – a role that the earlier conservationists had sought, but failed to realize - now became irresistible:

Here was a vast field in which governments – local, state and federal – could perform prodigious feats without stepping on the toes of private business. If government had not done this long before, it was due partly to incomplete realization on the part of both experts and laymen of this vital necessity, partly to the failure of penny-wise and pound-foolish Congressmen to appropriate the necessary funds. But now all this changed. Business was unable – in the Depression – to take care of the livelihood of large portions of the population. The government had to step in. Here was the golden opportunity to make up for decades, perhaps a century of neglect… (1951:571-572, original emphasis)

<33> Stepping-in required the coordination of a powerful central agency, a task that – with the changes in social attitudes alluded to above – was thrust upon the state. "Thus" declares Zimmermann, "the government entered the field of electric power generation on a vast scale" an intervention that "was merely incidental in a far vaster scheme of watershed control and regional resources development." (1951:574) Beginning in the 1930s, there followed several major water projects intended to engineer the fluvial topography of the United States: the great dams of the Tennessee Valley Authority; the Colorado River Projects; the Columbia River Basin Project; the California water projects (including the Central Valley Project, the Imperial Valley Irrigation District and the California State Water Project). Such projects, as Worster notes, were associated with an "immense ballooning of the state", a process that he argues has rendered the American West "a modern hydraulic society ." (1985:279,7) Whether one agrees with Worster or not, the state-sponsored water projects of the 1930s and after have certainly gone a long way toward realizing McGee's ambition of "conquest" of the nation's water by bringing it under "total control."[18]

IV – Conclusion - Before and Beyond Resources

When nature and human beings become natural resources and human resources, the process of abstraction and exploitation has already begun. A coconut is no longer celebrated as a coconut; a forest is no longer a forest when it is treated as a resource. Rather, the magic cover that existed for them, the totemic field that protected them, is stripped off and, as resources, they begin the long journey into the world economy. (Visvanathan 1991:240)

<34> The argument so far is that once a resource, nature is set to its most productive use, a determination that has the effect of denying the resources of some while allowing the resources of others. A resource, then, turns out to be a way of avoiding politics by translating questions of access and use into a language of calculation and technique. In this concluding part of the paper, I want to suggest that instead of resources, what matters most is the relations between people and things. The same thing may sustain myriad relations: a river may relate to some as a means of generating electricity, to others as a home for fish, a place of refuge, a subject of analysis, a space for recreation, a source of artistic inspiration, a barrier to cross, a mode of spiritual awakening, a metaphor of time. It is the variety of these relations, or modes of engagement, that accounts for different social natures of things like rivers and it is upon their recognition that a cultural politics of resources might be constructed.

<35> This relational view of things is consistent with a small but growing stream of post-dualist, post-natural approaches that geographers have adopted - approaches that refuse the fundamental philosophical nature-culture divide that grounds most modern (geographic) thought. Noel Castree has identified its adherents as "relational thinkers" who maintain "that phenomena do not have properties in themselves but only by virtue of their relationships with other phenomena. These relations are thus internal not external, because the notion of external relations suggests that phenomena are constituted prior to the relationships into which they enter." (Castree 2005:224) Applying this relational view, water becomes what it is in relation to other things and processes. [19]

<36> I'll start with a quote from Zimmermann, who dispenses with the popular misconception that waterpower is "free":

The idea of free water power would hardly occur to a generation that has had to foot large bills for hydroelectric developments – for dams, reservoirs, turbochargers, transmission systems, and all the various paraphernalia through which alone the nature-given force of rushing or falling water can be rendered articulate. (Zimmermann 1951:570)

The point Zimmermann wishes to make here is that water, as a power-generating resource, is a function of the fixed capital with which we sow our rivers. But surely he is being disingenuous. Anyone who has sat by "rushing or falling water" for any length of time knows of how it may be rendered articulate without the aid of dams, reservoirs, turbochargers, etc.. How water speaks and what it says differs enormously for different people. Some would argue that if anything, a river is silenced by a dam. The point is that in denying – or reducing to insignificance - the river itself (the riverness rather than the resourcefulness of the river), the functional approach precludes all the other possible ways by which it may articulate with people.

<37> Getting before and beyond the resource to the thing itself is, of course, an extremely tricky proposition. The whole idea of social nature is built on the foundation that we can never really know nature "as it is", outside of the cultural constructs, discourses and epistemologies that mediate our engagements with the world. If we are to get beyond resources, therefore, we will have to do away with nature entirely. This is no great loss if we accept that nature is nothing other than an artful means of distinguishing humans – and only a certain class of humans – from the rest of the world. This is clearly the case with respect to resources, where the functional approach posits a constitutional divide between nature and culture that is absolutely necessary to prevent us from descending to the status of animals or savages. If we can live with the demotion, it is possible to see that we differ from other beings not by virtue of our wisdom, adaptability, cleverness etc, - not because we alone posses the ability to turn neutral stuff into resources - but by the different sorts of relations that we have with things like rivers, forests, rocks, plants, other animals and other people.

<38> Getting rid of nature, and resources, we are left with the things themselves, the "stuff" – which is no longer as neutral as it may have seemed when we allowed only for the resourcefulness of the world to present itself. For Zimmermann, something is either useful to us or it is meaningless. A thing may be appraised as a resource, or it is neutral stuff. "[T]he world" is literally "the sum total of man's resources." (1951:7) Such a world precludes all other kinds of relations between people and things like rivers except that of supplying the means to furnish the ends of the appraiser. But surely there are other modes of apprehending things beyond disclosing their resourcefulness, and there are ways of relating to things other than as raw material.[20] Consider the following comments by Chief Kathy Francis of the Klahoose Nation of British Columbia made at a conference on the subject of bulk water exports:

You have heard this morning from speakers who see water as just another "resource" – something to be captured or tamed, put in containers or otherwise diverted from its natural path, and transported far away to be used and sold for money. Perhaps from that perspective, one can somehow convince oneself that under certain circumstances water export could make sense.

To First Nations people, however, water is seen very differently. A creek, which to a non-native person may be seen simply in terms of flow rates and acre-feet per year, may have a special name and spiritual significance. It may be a private bathing place for special ceremonies or initiation rites, or in some cases be owned by a particular individual or family. It not only physically and spiritually cleanses people, but it also cleanses the earth and, eventually, the sea to which it inevitably flows, if left alone. (Francis 1992:94)

One has difficulty translating this appraisal of water into resources. Possessing a special name, holding religious significance, serving as a site of special ceremonies or rites, acting as an agent of spiritual cleansing and even as something, which, "if left alone" cleanses the earth and the sea – hardly describes the resourcefulness of water. Rather, it describes a few of the infinite variety of relations that water is capable of sustaining – with people, with the earth, with the sea. It is through such relations that water becomes what it is in every particular instance. And it is water's potential for sustaining such relations as these that gets destroyed by those who hear nothing in moving water but the articulation of power, who presume the universal fitness of their own particular mode of appraisal, and who have the strength to impose the relations that flow from it.

<39> But what is water in the first instance, before it becomes the things that we make of it? Perhaps it's best to leave it to itself, to its own blue chaos out of which flows so much potential. In the first instance, what is water but a blue chaos? The philosopher and historian of religion, Mircea Eliade, wrote that water "is fons et origio, the source of all possible existence…; it will always exist, though never alone, for water is always germinative, containing the potentiality of all forms in their unbroken unity." (1958:188, 189) The notion that water always exists, but never alone, is to acknowledge that it exists in every particular instance in relation to something else. The notion that water contains the potentiality of all forms is to underscore the infinite variety of relations that water is capable of sustaining. What then ought to be our attitude towards water but to recognize the potentiality it contains and allow it to retain as much of its capacity for germination as possible? Rather than protecting water resources or maximizing the beneficial uses of water, perhaps the aim of water management ought to be to sustain its chaotic potential, to allow it to entertain as many relations as possible.

<40> Thinking of our relations constrains us from seeing them in purely abstract, utilitarian terms as may be promoted in resource conservation and development. Instead, our attention is drawn to how some relations (i.e. between people in southern Canada and rivers in the north, mediated by dams, dynamos and hydro-electric transmission lines) militate against others (i.e. between people in the north and rivers as modes of transportation, sources of sustenance, holders of religious significance, sites of special ceremonies and rights, agents of spiritual cleansing). Bill Namagoose, then Executive Chief of the Grand Council of the Crees of Northern Quebec, noted this discrepancy when addressing the question of expansion of the James Bay hydroelectric project in 1991: "There are two ends to a hydro line. There's the luxury end, the comfortable end. Lights, heat, cooking, there's music coming out of that end of the line. But at our end of the line, we don't hear music. We hear massive destruction." (quoted in Desbiens 2004:113)

<41> Thinking before and beyond resources allows us to see that what's at stake is more than a matter of efficiency. What's at stake is the choice of how something like water is taken to be and what kind of relations it is allowed to sustain. Different waters sustain different kinds of relations. The water of some can be destroyed by the water of others. In observing the effects of a hydroelectric development, Bill Namagoose lamented its simultaneous, mutual assault on a river and a culture. The costs of bringing order to the blue chaos in the usual manner are particularly apparent to those whose waters are most directly affected. But defining the resourcefulness of water is always a political act, and is increasingly being recognized as such by all who wish to sustain different kinds of relations.

Figure 1 – We hardly notice when water is represented to us as a resource – its resourcefulness is quite invisible. Illustration from "The World's Water Supply", an article appearing in a National Geographic special issue on water. (From Parfit 1993:24) [^] [^]

Figure 2 – Zimmermann's depiction of culture driving ever deeper into the realm of nature, converting neutral stuff into resources. (from Zimmermann 1951:13) [^]

Works Cited

Barnes, Trevor J. 2001. Retheorizing Economic Geography: From the Quantitative Revolution to the "Cultural Turn." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 91, no. 3: 546-565.

Braun, Bruce. 2002. The Intemperate Rainforest: Nature, Culture, and Power on Canada's West Coast. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Castree, Noel. 2005. Nature. London and New York: Routledge.

Castree, Noel and Bruce Braun, ed. 2001. Social Nature: Theory, Practice and Politics. Malden, Mass. and Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Cutter, Susan L, Hilary Lambert Renwick and William H. Renwick. 1991. Exploitation Conservation Preservation: A Geographic Perspective on Natural Resource Use. Second Edition. New York: Wiley.

Desbiens, Caroline. 2004. A political geography of hydro development in Quebec. The Canadian Geographer 48, no. 2: 101-118.

Eliade, Mircea. 1958. Patterns in Comparative Religion. Translated by Rosemary Sheed. London and New York: Sheed and Ward.

Fitzsimmons, Margaret. 1989. The Matter of Nature. Antipode 21, no. 2: 106-20.

Francis, Chief Cathy. 1992. First they came and took our trees, now they want our water too. In Water Export: Should Canada's Water Be For Sale? Proceedings of a Conference held in Vancouver, British Columbia on May 7-8, 1992., ed. J.E. Windsor:93-102. Cambridge, Ontario: Canadian Water Resources Association.

Hanink, Dean. 2000. Resources. In A Companion to Economic Geography, ed. Eric Sheppard and Trevor J. Barnes. Oxford and Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers.

Harvey, David. 1996. Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hays, Samuel P. 1959. Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Heidegger, Martin. 1977. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Translated by William Lovitt. New York: Harper and Row.

Johnston , R.J, Derek Gregory, Geraldine Pratt and Michael Watts. 2000. The Dictionary of Human Geography. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell.

Langbein, Walter B. and William G. Hoyt. 1959. Water Facts for the Nation's Future. New York: The Ronald Press Company.

Leighton, M.O. 1909. Water Power in the United States. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 33: 535-565.

McCully, Patrick. 1996. Silenced Rivers: The Ecology and Politics of Large Dams. London and New Jersey: Zed Books.

McGee, W.J. 1895. The Beginning of Agriculture. The American Anthropologist 8: 350-375.

McGee, W.J. 1909. Water as a Resource. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 33: 521-534.

McGee, W.J. 1911. Principles of Water-Power Development. Science 34, no. 885: 813-825.

Meredith, Thomas. 1995. Assessing Environmental Impacts in Canada. In Resource and Environmental Management in Canada: Addressing Conflict and Uncertainty, ed. Bruce Mitchell:360-383. Don Mills: Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, Bruce. 1989. Geography and Resource Analysis. Second Edition. New York and Essex: John Wiley and Sons Inc. and Longman Scientific and Technical.

Mumford, Lewis. 1934. Technics and Civilization.

Nace, R.L. 1978. Development of Hydrology in North America. Water International 3, no. 3: 20-26.

Nelles, H.V. 1974. The Politics of Development: Forests, Mines and Hydro-Electric Power in Ontario, 1849-1941. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada.

Newell, Frederick Haynes. 1920. Water Resources: Present and Future Uses. New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Oxford University Press.

Ollman, Bertell. 1993. Dialectical Investigations. New York, London: Routledge.

Parfit, Michael. 1993. Sharing the Wealth of Water. National Geographic Special Edition: "Water": 20-37.

Rees, Judith. 1990. Natural Resources: Allocation, economics and policy. London and New York: Routledge.

Reuss, Martin. 2001. Hydrology. In The History of Science in the United States: An Encyclopedia, ed. Marc Rothenberg:274-276. New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc.

Rogers, Peter. 1996. America's Water: Federal Roles and Responsibilities. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Shiva, Vandana. 2002. Water Wars: Privatization, Pollution, and Profit. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Visvanathan, Shiv. 1991. Mrs. Brundtland's Disenchanted Cosmos. Alternatives 16: 377-384 (Reprinted in O Tuathail, Gearoid, Simon Dalby and Paul Routledge eds. 1998.The Geopolitics Reader. London: Routledge, 237-241.).

Whatmore, Sarah. 2002. Introduction: More than Human Geographies. In Handbook of Cultural Geography, ed. Mona Domosh Kay Anderson, Steve Pile and Nigel Thrift:165-167. London: Sage Publications.

Worster, Donald. 1985. Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West. New York: Pantheon Books.

Xenos, Nicholas. 1989. Scarcity and Modernity. London and New York: Routledge.

Zimmermann, Erich W. 1933. World Resources and Industries: A functional appraisal of the availability of agricultural and industrial resources. New York and London: Harpoer and Brothers Publishers.

Zimmermann, Erich W. 1951. World Resources and Industries: A functional appraisal of the availability of agricultural and industrial materials. Revised Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers.

Notes

[1] This sentence summarizes the main argument of the Ph. D. thesis that I am currently in the final stage of completing. [^]

[2] In the broadest sense, the present work finds its place in a field of research that goes by the name (among some geographers at least) of "social nature." (cf Fitzimmons 1989; Castree and Braun eds. 2001; Braun 2002; Castree 2005) As might be inferred from such a hybrid term, it represents an endeavour to collapse the usual modern categories in a way that might, hopefully, encourage more heterogeneous and just socionatural relations. For a useful introduction to this mode of thinking nature see Harvey 1996. [^]

[3] Samuel Hays described McGee as "the chief theorist of the conservation movement." (Hays1959:102) [^]

[4] McGee's paper is representative of the views of contemporary progressives interested in promoting the conservation of water, most notably F.H. Newell and M.O. Leighton. (See Hays 1959 generally; Leighton 1909; Newell 1920) [^]

[5] This is the essence of the functional definition of resources, discussed below. [^]

[6] The term "conservation," in the context of the early 20 th century movement in the U.S., appears to have been applied first to water, and it meant literally storing water behind a dam so as to bring water under control, to smooth out its irregularities and render it standing reserve for its efficient application to the most economical, productive uses. (Hays 1959; Newell 1920) [^]

[7] Known to American hydrologists as "the father of systematic stream gauging" (Nace 1978:22) and described by Hays as "one of the architects of water policy and of the entire conservation movement" (1959:7) [^]

[8] Apparently, circumstances had changed slightly from 1909 to 1911, as in the latter year, McGee prescribes a hierarchy of water uses that begins with the use of water for "drink and other domestic supply" followed by "agriculture, including irrigation", "mechanical power", and finally "navigation." "Yet", he adds, "the several uses may and should be combined, as when water for domestic supply or irrigation is used for power – and the development of power generally promotes navigation." (McGee 1911:817) [^]

[9] As a classic illustration of the contemporary appreciation of water's resourcefulness, serious concerns were raised around this time that the scenic value of Niagara Falls would be sacrificed to the interests of maximizing the generation of hydro-electricity. (Nelles 1974:311-326) [^]

[10] Such as the Boulder (later to be named the Hoover) Dam, begun in 1931. [^]

[11] The second edition, published in 1951, presents the same approach, but in an updated version, the importance of which (updating to keep abreast of new technologies and modes of exploiting resources) is integral to the functional approach. [^]

[12] Mitchell 1989; Rees 1990:12; Cutter, Renwick and Renwick 1991:1; Meredith 1995:362; Hanink 2000:227; Johnston et al. 2000:535. Moreover, Zimmermann's functional approach is held by many to be "as relevant today as when first proposed in 1933." (Mitchell 1989:1; see also Hanink 2000:227) [^]

[13] He was as inclined – particularly in the 1933 edition of his book - to champion conservation as "a business proposition" as much as a sacred public trust. (Zimmermann 1933:784) [^]

[14] For the cultural turn in geography see (Johnston et al. 2000:141-143; Barnes 2001). [^]

[15] He admits that it is "almost impossible to determine" the direction of this movement. But the progressive bias in the concept is unmistakable: "Studying the western world during the last few centuries, one may be inclined to view the movement as following an ascending spiral. Wants multiply, arts improve, ever higher tiers of cultural improvements are superimposed on the natural foundations." (Zimmermann 1933:9) "Yet while changed or expanding wants create new resources, others are destroyed. Progress always means a net gain but seldom a pure gain. Creating the better, we must often destroy the good." (Zimmermann 1951:17) [^]

[16] Caroline Desbiens' assessment of the first phase of the James Bay hydroelectric project in Northern Quebec provides a good example of the latter: "[C]onstructions of James Bay's nature by the South became constructions of who had a right to claim such a space for purposes of (narrowly understood) economic development. The Crees' own modes of occupation and interaction with James Bay and its resources could hardly be represented in this imagined geography since it did not admit multiple frameworks for understanding and interacting with nature, which it regarded as an objective category. While knowledge of James Bay for Southern actors was generated in a particular social context, the sharply unequal balance of power at the time worked to universalize that context and thus predetermine whose knowledge would influence policy decisions in the area." (Desbiens 2004:107) [^]

[17] See Zimmermann 1951:15-17 for elaboration of this "scientific framework". [^]

[18] Readers might find Worster's description of the plumbing of the North American continent relevant: "It drips endlessly from the roof of North America, from the cordillera of the Rockies, down from its eves and gables and ridges… Put a barrel where it drips, and a second next to that one, and so on until the yard is full. [Worster then lists dozens of large dams in the American West] Barrel after barrel, each with a colourful name but all looking alike, quickly becoming an industry in their manufacture, with industrial sameness in their idea and use…Everywhere barrels filling in the spring, barrels emptying out again in the dry season. Plink, plink, save, save. It would have been a crime simply to stand by and watch it drip and run away." (Worster 1985:266-7) [^]

[19] Some readers will recognize in this a variant of dialectical thinking. Perhaps the foremost proponent of relational thinking in geography is David Harvey, who applies it in an approach he describes as "relational dialectics." ( Harvey 1996) For an elaboration of this aspect of dialectical thought, see Ollman 1993. [^]

[20] As already noted, perhaps the most thoughtful exponent of this idea in the Western tradition is Heidegger. See especially Heidegger 1977. [^]