Reconstruction 7.2 (2007)

Return to Contents»

Contemporary Art Facing the Earth's Irreducibility / Amanda Boetzkes

Abstract: This article considers the aesthetic strategies and ethical implications of contemporary earth art. Drawing from feminist and ecological phenomenology, I argue that an ethical preoccupation with the earth is identifiable in works that evoke the sensorial plenitude of natural phenomena, but refuse to condense it into a coherent image or art object. By denying a perceptual grasp of the earth, contemporary earth artists question the possibility of representing it as such. They thereby position the earth as a territory of alterity that exists beyond our conceptual and perceptual limits. This approach counters two deeply flawed but nevertheless pervasive stances towards the earth: the instrumental view, that seeks to master the planet through an exclusively human-centered knowledge of it, and the romantic view, that we can return to a state of unencumbered continuity with nature. I will address the site-specific works of the British artist Chris Drury, the Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta, and the American artist Jackie Brookner, each of which features the contact between the artist's body and the earth. In particular, these artists perform the intermingling, and subsequent partitioning, of the body from the earth's material. That is to say, they assert the body as a surface that separates itself from the earth, and at the same time provides a surface on which the ephemeral materializations of nature occur. The earth appears on the performed body in influxes of light and colour, the appearance of spectral shapes, or in a flourish of growth. While evoking an abundance of sensation, however, these transient expressions disclose the earth's withdrawal from a totalized representation. Raising the ethical paradigms of the feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray and the eco-phenomenologist Mick Smith, I suggest that the artworks in question retract from an immersive experience of the earth, and enact a 'facing' of its irreducibility. Shifting from the intimacy of dwelling in the earth to the opaque face of nature that confounds our knowledge of it, artists mobilize an aesthetic experience that opens up an ethical acknowledgment of the earth's alterity.

<1> This article considers the aesthetic strategies and ethical implications of three contemporary earth artists. It addresses the site-specific works of the British artist Chris Drury, the Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta, and the American artist Jackie Brookner, each of whom feature the contact between the artist's body and the earth. In particular, these artists demonstrate the intermingling, and subsequent partitioning, of the body from the earth's material. They thereby position the earth as a territory of alterity that exists beyond our conceptual and perceptual limits. Drawing from feminist and ecological phenomenology, I argue that an ethical preoccupation with the earth is identifiable in the way the artworks evoke the sensorial plenitude of natural phenomena, but refuse to condense it into a coherent image or tangible art object. By denying a perceptual grasp of the earth, the artists question the possibility of representing it as such. Through the ethical paradigms of the feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray and the eco-philosopher Mick Smith, I suggest that the artworks in question retract from an immersive experience of the earth, and enact a 'facing' of its irreducibility. This approach counters two pervasive but nevertheless deeply flawed stances towards the earth: the instrumental view, that seeks to master the planet through an exclusively human-centered knowledge of it, and the romantic view, that we can return to a state of unencumbered continuity with nature.

Beyond Dwelling in the 'Flesh of the World': Encounters with the Irreducible Earth

<2> According to the art historian Rosalind Krauss, the beginning of the earthworks movement in the late nineteen-sixties can be understood as part of a larger trend in sculpture to fully integrate the art object into the space that it occupies. [1] Early earth artists such as Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, and Richard Serra built their works into the land so that the art object and the environment were inextricable from one another. By situating their monumental sculptures - objects that by sheer size alone defied the confines of the gallery - in vast and uninhabited landscapes, they lodged a critique of the modernist ideal that the meaning of an art object transcends its literal environment. The aesthetic experience of an earthwork (presuming the spectator could even access the site) was therefore bound to an expanded perceptual field that included the variable conditions of the area: its topography, geological material, and ever-changing atmosphere. Earth artists rejected the supposedly disembodied experience of a self-enclosed modernist art object , by collapsing the sculpture into the site and insisting on a bodily engagement with the earthwork from within it. [2]

<3> The idea that the artwork is a space that must be inhabited in order to be apprenhended, prompted Krauss to theorize works such as Richard Serra's Shift (1970; Figure 1) through the principles of Maurice Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenology of Perception (1945). [3] For Krauss, earthworks demonstrate an essential facet of perception as explained by Merleau-Ponty's phenomenology: the visual field is informed by the bodily perception of being immersed in a space, and is oriented through the varying relations with other people and things in that space. In Shift, for example, Serra executed an earthwork that enacted this kind of sited vision, organizing a sculpture that would mark the interlocking of looks between two people as they moved across the land. Serra, and artist Joan Jonas, positioned themselves on either end of a three hundred yard field and walked across it on opposite ends, always keeping each other in view despite upsets in the land, from swamps to hills and trees. Serra explains, " The boundaries of the work became the maximum distance two people could occupy and still keep each other in view ... What I wanted was a dialectic between one ' s perception of the place in totality and one ' s relation to the field as walked." [4]

<4> Serra placed short concrete walls at the points where his and Jonas' eye-levels aligned, and these walls functioned as orthogonals. However, in contrast to the fixed orthogonal that directs the gaze to a central vanishing point in Renaissance perspective, these stepped elevations that sometimes rise at a diagonal out of the ground or change direction suddenly, reveal that one ' s horizon is continually shifting, or in Serra ' s words, "... they are totally transitive: elevating, lowering, extending, foreshortening, contracting, compressing, and turning." [5] Serra and Jonas show that one's perspective is inextricable from the particularities of one ' s physical surroundings. The variations in the topography of the land generate a continually moving horizon as one walks over it. By introducing a scenario dependent on the spectator ' s movement through space, and the reciprocal gaze of another person, Shift breaks with the stable environment of the museum that encourages a singular orientation centered on an art object. Here, the relation between oneself, the other, and the topographic specificities of the external space constitutes the artwork.

<5> It is hardly surprising that the analysis of early earth art called upon Merleau-Ponty's phenomenology. Shift clearly speaks to that theorist's statement in the Phenomenology of Perception that, " I know the relation of appearances to the kinaesthetic situation... not in virtue of any law or in terms of any formula, but to the extent that I have a body, and that through that body I am atgrips with the world (my emphasis)." [6] Indeed, in The Visible and the Invisible (1964), a text that has been influential for art historians of postminimalist sculpture and performance art, Merleau-Ponty further advances his argument that bodily perception is grounded in the fabric of the world. [7] Through the metaphor of the chiasm, he describes an intercorporeal relationship with the world, whereby what we know of ourselves and others is generated by a sense of the body's flesh as intertwined with, what he calls, 'the flesh of the world'. Merleau-Ponty writes, "...the presence of the world is precisely the presence of its flesh to my flesh, that I am of the world and that I am not it..." [8]

<6> Merleau-Ponty's 'flesh ontology' clearly resonates with certain aspects of early earth art, specifically, the possibility of seeing the artwork in relation to the land, and considering the variations in the land as active components of the aesthetic experience. It is important to stress, however, that although Serra's work and others like it locate the artwork within the world flesh, this is not to suggest that they are necessarily advancing an ethical stance towards the earth itself. In more contemporary practice, however, earth artists have focused their attention more specifically on the way in which natural phenomena can disrupt or challenge the coherence of embodied perception.

<7> Where the first generation of earth art emphasizes a shared corporeality with the earth, recent artistic practices reconfigure the relationship between the body and the earth, foregrounding the way in which the earth escapes and even disrupts our perceptual 'grip' of it. These spontaneous, uncontrollable and even alien outbursts cannot be integrated into a coherent perception, though, as artists show, they are nevertheless abundantly sensuous. Contemporary earth art draws an important distinction between what we can definitively 'know' of the earth through our individual perception of it, and a more subtle mode of sensation which suggests that the earth's existence is beyond our perceptual field.

<8> The importance of acknowledging the excess of the other, and of the world, underpins Luce Irigaray's critique of Merleau-Ponty's phenomenology. [9] Irigaray argues that Merleau-Ponty's framework for perception initiated in his Phenomenology of Perception and later developed in his ontology of the flesh in The Visible and the Invisible, is based on a metaphor of the nocturnal state of being in the womb. She argues that at no point in Merleau-Ponty's model of the chiasm does he delineate a recognizable separation between oneself and the flesh of the world. Merleau-Ponty thus refuses to identify a point of birth and separation from that world flesh. The earth thus becomes a landscape of the maternal body to which the subject has unencumbered tactile access. Irigaray maintains that without acknowledging the necessary process of differentiation, the result is a model of perception based on solipsism. All sensation becomes translated into sameness, merely fulfilling ones perceptual expectations so that no true understanding of difference can register. In Merleau-Ponty's chiasm, she argues:

...something is said about the fact that no mourning has been performed for the birth process, nor for the cutting of reversibility through some umbilical cord. Although a pertinent analysis of the way I form a weave of sensations with the world, it is one that excludes solitude even though its own systematization is solipsistic. The seer is never alone, he dwells unceasingly in his world. [10]

<9> Without an acknowledgment of fundamental separation, the subject can never understand the earth as anything other than what he or she perceives of it from within the limits of one's individual experience. The Merleau-Pontian subject, for Irigaray, "...never emerges from an osmosis that allows him to say to the other...'Who art thou?' But also, 'Who am I?' What sort of event do we represent for each other when together? ... The phenomenology of the flesh that Merleau-Ponty attempts is without question(s)." [11] Perception, in this mode, risks subsuming the earth into the limited parameters of individual (and exclusively human) knowledge. In connection with Irigaray's critique of Merleau-Ponty, the eco-philosopher Mick Smith connects the dormant solipsism of certain modes of perception to the environmental crisis, arguing that an overemphasis on tangibility is symptomatic of an instrumental view of the earth. When we reduce the earth to mere matter, he argues, we become oriented towards "things that exhibit a paradigmatic materiality, that are solid, fixed, bounded, isolable..." [12] As Smith succinctly argues, instrumental logic operates in accordance with a mechanics of solids, denying that which is permeable, fluid and less tangible.

<10> In light of these ethical and ecological critiques of phenomenology, it is important to investigate not just how an artwork is interconnected with the earth, as has often been the case in the analysis of early earth art, but more precisely how an artwork calls into question our mode of perception, and reveals the earth's resistance to being perceived by humans. I will now turn to three contemporary earth artists, Chris Drury, Ana Mendieta, and Jackie Brookner, whose site-specific works each articulate a physical relationship with the earth but nevertheless reveal a point at which the earth exceeds our perceptual framework. Each artist thus responds to the goal of the early earthworks movement of positioning an artwork (whether it be a sculptural object or a performative gesture) in relation to a natural site, and of thereby mediating the spectator's bodily experience of that site. However, I will argue that more than simply providing an immersive experience of the natural site, these artworks stage the kind of event that Irigaray calls for: an encounter between the artist and the earth as other, where the earth is located beyond our limits of perception but is nevertheless a network of activity and events to which the artwork is connected.

Chris Drury's Wave Chamber: Surfacing the Earth from Within

<11> At the heart of Irigaray's project is another way of recognizing the other's alterity in the events that perplex us and overturn our knowledge. These events call us to draw back and reassess our perceptual intentions towards the other, opening up a breathing space within the dense musculature of Merleau-Ponty's flesh ontology. The possibility of seeing the earth through events that confound our perceptual expectations is precisely what is at stake in the cloud and wave chambers of the British artist Chris Drury. Since the early eighties, Drury has constructed shelter-like structures in rural areas around Britain. [13] Like the first generation of earthworks, Drury's works are woven into a natural site, built out of stone, grass, turf, wood, soil, or whatever materials are available. On one level, the shelter 's function is to create an interior space: it is at once a surface membrane and an inner sanctuary. Yet, from within, the threshold of the shelter acts as a frame that is inevitably exceeded by the exterior landscape. Drury comments on these two contrasting perspectives saying, "I like the way that a shelter has an interior and an exterior ...I like the way this interior space draws you inside yourself, enclosing, protecting, just as mountains pull you outside yourself, pushing mind and body beyond their usual confines. " [14] The artist thus describes two diverging trajectories: a deep introspection produced by physical enclosure and a call from outside one 's boundaries, a demand that stretches the limits of what we can see.

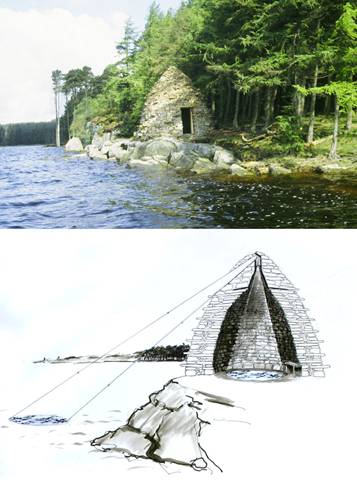

Figure 1. Chris Drury. Wave Chamber, dry stone with mirror and lens in a steel periscope, Northumberland, 1996. © Chris Drury.

<12> Not entirely satisfied with this alternation between interior and exterior that his shelter projects in the eighties enact, however, in the mid-nineties, Drury introduced a two-dimensional image into the three-dimensional space of the shelter. He called these works cloud or wave chambers. The chamber situates the visitor in a dark earthen space, and invites an intensified bodily experience of being enclosed in the site. But in addition to this immersive situation, Drury adds a pictorial dimension. The chamber functions as a camera obscura: he places a periscope lens at the top of the structure that projects reflected images of the landscape onto the wall or the ground. This projection is replete with movement, and is visually compelling because of its vaporous quality as well as its transient colors and textures. Wave Chamber (1996; Figure 2), for example, reflects the moving water onto the ground, so that the visitor cannot grasp the image from a clear vantage point, as one might a landscape painting on a wall. Rather, the image surrounds the visitor like atmosphere. Drury describes entering Wave Chamber for the first time upon its completion, "At that moment the afternoon sun was hitting the water just where the mirror was angled. Inside it was as if a thousand silver coins were dancing across the floor. As the sun moved away, this changed to ghostly ripples, giving you the feeling of standing on liquid." [15]

<13> Although Jonathan Crary has argued that historically, the camera obscura was implicated in a metaphysics of interiority whereby the body of the observer is rendered ambiguous and vision decorporealized, Drury's chambers have the opposite effect. [16] Rather than severing vision from the body and thus staging a mind/body dualism, the darkness of the chamber is the condition for an intensified physical engagement with the visual spectacle of the periscope image. One is not delivered from the body into a coherent abstraction, as Crary suggests of the camera obscura. Instead, in the wave chamber the senses are saturated by an abundance of natural phenomena in flux. The periscope funnels the site into the chamber and makes it visible in perpetual motion. Drury thus complicates pictorial modes of confrontation by providing an image that changes unpredictably in rhythm and intensity. The image refuses to deliver the site via the substantial reassurance of a tangible object or a centrally organized perspective of a landscape. The chambers share the material of the site and actually lead the visitor deeper into it. At the same time, however, they deny the closure of the perceptual intention (or grip) that characterizes Merleau-Ponty's description of the eye as a quasi-hand that "envelops" and "palpates" its object of attention. [17]

<14> We could read Wave Chamber as an allegory of an ethical mode of sensory exploration. The artwork is an aperture through which the earth manifests without being assembled into a coherent entity that can be known. The chamber approximates a chiasmic tie; it surrounds the visitor in the site's 'flesh,' and envelops the ephemeral periscope image analogously to a Merleau-Pontian eye that closes around the object. Yet, the chamber offers no object, nor a still image of the site. The site is entirely present, for it illuminates and animates the chamber, but the unpredictable movement of the water resists a conclusive perception. Drury's Wave Chamber troubles two presumptions: firstly, that our continuity with the earth is seamless, and secondly, that an absolute and intimate perception of the earth can be gleaned from this intercorporeal relation. Instead of offering the earth as tangible substance, Drury facilitates a spectacle of transient natural phenomena, insisting on a retraction from perceptual closure. It thus summarizes the ethical impetus of earth art - to provide a sensation of the natural site as an excess beyond our limits of our perception.

Ana Mendieta's Siluetas: Retraction and Reciprocal Touch

<15> Cuban-American performance artist Ana Mendieta, similarly illustrates the complexity of sensing the earth in her Silueta Series, a series of photographed performances from the late seventies and early eighties, in which the artist impressed her body into the land. [18] Mendieta's "earth-body sculptures," as she called them, complicate the relationship between the body and the earth by figuring the body as a simultaneous presence and absence on the earth's surface. The silueta evidences the body's continuity with the earth's material, but also stands as a trace of its extrication from that material. Mendieta's series prompts the sensation of tactile friction between the body's surface and the land. By constructing the imprint out of earthly matter - rocks, flowers, water, fire or ice - and enacting the metamorphosis of the imprint as this matter changes, the artist suggests an intercorporeal relation with the earth, but insists that in its boundlessness, the earth overwhelms and reconfigures the parameters of the body. The silueta does not suggest a straightforward fusion or union with the earth. It evokes tactile friction between the surface of the body and the surface of the land, putting physical continuity and differentiation into conversation. The result, as in Drury's WaveChamber, is a flowering of transient natural activity. In Mendieta's case, however, the earth appears at precisely the locus where the artist has emblematized her retraction from it - the imprint.

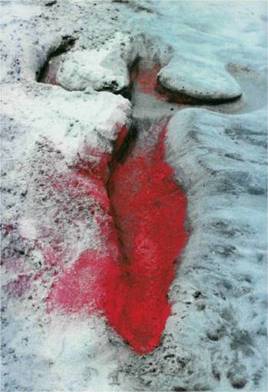

<16> In Untitled (Figure 3), executed in Oaxaca, Mexico in 1976, Mendieta made a silueta that acted as a vessel that would catch an influx of water. The imprint was recessed deeply into the sand on a beach so as to interact with the waves as the tide rolled in. To galvanize the contact between the silueta and the water, Mendieta lined the silueta with red pigment. As the water advanced, it filled the imprint, its swirling eddies mingling with the color. Gradually, - and Mendieta gives us a sense of this temporal process by photographing the performance in a series of 35mm color slides rather than one single photograph - the water overtook the imprint, rounding out and breaking its outline and finally carrying the pigment back into the ocean.

<17> Using the color to foreground the silueta's boundaries, Mendieta tracks the trajectory of the water, and pictures the rhythm of the tide as an entry into and exit from the performed body. The artist thus enacts her contact with the site as an open-circuitry: an inflow and outpouring of water across the limits of the body. The final photograph in the sequence of slides is not an image of the beach after the silueta has completely dissolved. Instead, the artist closes the performance with an image of the imprint that remains only partially defined by a curved ridge in the sand (Figure 4). The diluted pigment swells in the water against the ridge that pushes back against the surging tide. This ridge of sand summarizes the body-earth relation that Mendieta achieves. It maintains the shape of the body's profile, and foregrounds the pressure of the water against it. Over the course of the performance, the body is neither fully absorbed by the earth, nor is it entirely isolated from it. The aesthetic basis of the performance lies in the continual reconfiguration of the boundary between the body and the earth, and the evoked sensation of friction that this shifting boundary generates.

Figure 2. Ana Mendieta. (Untitled) Silueta Series, sand and red pigment, performance photographed in a series of 35mm color slides, 1976, Oaxaca, Mexico. © Estate of Ana Mendieta courtesy of the Galerie Lelong, New York.

Figure 3. Ana Mendieta. (Untitled) Silueta Series, sand, red pigment, final image of performance photographed in a series of 35mm color slides, 1976, Oaxaca, Mexico. © Estate of Ana Mendieta courtesy of the Galerie Lelong, New York.

<18> As visually rich as this performance is, there is also a strong tactile foundation to it, particularly in the final image of the ridge of sand. However, it is important to point out that Mendieta forwards a distinct mode of touch that reveals the unfixability of the site. Luce Irigaray best explains the ethical potential of this tactile logic in her critique of Merleau-Ponty. Irigaray points out the asymmetry in Merleau-Ponty's argument about the reversibility of tactile sensation - his statement that to touch is always also to be touched, from which he extends the claim that to see is always also to be seen. [19] Merleau-Ponty proposes the experience of one hand touching the other as a metaphor of the double sensation at play in our perception of others and the world. In this scenario, one hand has access to the other, and the subject simultaneously feels with the one hand and is felt by the other. Irigaray counters that this analogy betrays a structural hierarchy, for one hand covers the other and even 'takes hold' of it without ever being touched by it. In this paradigm, she argues, "We never catch sight of each other ...Within this world, movement is such that it would take extraordinary luck for two seers to catch sight of each other." There is, "no Other to keep the world open [20]," and indeed, the world itself cannot be Other, it can only by one's own world.

<19> Irigaray posits an image that alters Merleau-Ponty's case of one hand touching the other. She evokes as a model of a tactile exchange between oneself and the other - the image of two hands joined at the palms, with fingers stretched as though in prayer: a relation of reciprocity. [21] The point here is not the similarity of the one to the other (Irigaray is explicit about this) but rather that in the relation of simultaneous feeling-felt there is a passage between oneself and the other, by which the other can freely express, and from which one can sense that expression, without covering it over in one's perceptual intention. This contact, she explains, evokes and doubles the touching of lips, silently applied to one another. The intimate touch of the lips allows for openness, one never closes over the other. They, "remain always on the edge of speech, gathering at the edge without sealing it." [22] Most interestingly, Irigaray employs the metaphor of the two hands joined at the palms to describe the possibilities of seeing the other. This gesture, she continues, "could also be performed with the gaze: the eyes could meet in a sort of silence of vision, a screen of resting before and after seeing, a reserve for new landscapes, new lights, a punctuation in which the eyes reconstitute for themselves the frame, the screen, the horizon of vision [23]."

<20> Mendieta performs the contingency of the body and the earth, and pictures it as this relation of feeling-felt with an other presence. The ridge of sand that concludes the performance not only expresses a relation of reciprocal touch between the body and the earth, it recapitulates this sensation visually for the spectator through the push and pull of colored water against the silueta.

The Body-Earth Relation as Face-to-Face

<21> Up until now I have emphasized that Drury and Mendieta establish a sensorial encounter with the earth, as though the earth were not only tangible material, but an unfathomable presence engaged in a kind of quasi-intersubjective exchange with the artist. Though this argument risks anthropomorphizing the earth and thus re-iterating the solipsistic phenomenology that Irigaray critiques, in fact, I am arguing that earth art entails a 'facing' of the earth's otherness, not its humanness.

<22> Irigaray's elaboration of an ethics of alterity is influenced by Emmanuel Levinas' work, and specifically his paradigmatic ethical encounter, the face-to-face. In this scenario the other addresses me with an appeal, a need, or an intrusion that must be heeded. As Tina Chanter explains, for Levinas, the realization of the other's alterity, the confrontation with the other's 'face' initiates the recognition of one's own subjectivity. [24] Self-awareness is preceded by the other's call to responsibility, and subjectivity is a consequence of the other's challenge or command to respond to its needs. Where Merleau-Ponty positions the self and the other in a precognitive chiasmic tie, Levinas founds the emergence of the subject on an ethical demand. In Mick Smith's view, the ethical command is not an alien infringement on the autonomy of a separable and pre-given self, but a constituent and primary passion at the heart of a relational self. [25]

<23> What links Irigaray to Levinas, is that both insist on the unrepresentability of the other, while at the same time expressing the encounter with the other, indeed the experience of otherness, in sensorial terms. The face-to-face is a particular mode of contact with the other in which alterity permeates the senses but is unrepresentable. As Levinas puts it,

The way in which the other presents himself, exceeding the idea of the other in me, we here name face. This mode does not consist in figuring as a theme under my gaze, in spreading itself forth as a set of qualities forming an image. The face of the Other at each moment destroys and overflows the plastic image it leaves me...It does not manifest itself by these qualities...It expresses itself. [26]

<24> Alphonso Lingis further explains that we navigate our relation to the other in 'the elemental', a material realm that mediates our sensations of the other's texture, contour, and boundaries. Conversely, we also understand the elemental through that relation with the other. Lingis writes, "We do not relate to the light, the earth, the air and the warmth only with our individual sensibility and sensuality. We communicate to one another the light our eyes know, the ground that sustains our postures, and the air and the warmth with which we speak." [27] Accordingly, for Levinas, the face-to-face occurs within this elemental medium. Lingis posits that it is not merely the ethical imperative of recognition, but also a demand for contact - to be physically received and reciprocated. This is why, the other's face does not necessarily manifest as a look, but as a gesture, a pressure on the hand, or a shiver of the skin. Facing requires a surface of exposure; he writes, "the skin...supports the signs of an alien intention and alien moods [28]." The elemental is crucial here, for it yields the face of the other.

<25> But can the elemental allow us to face the earth itself as an other? Can it call us into a sensorial awareness of the earth without anthropomorphizing it, or to use Irigaray and Levinas' vocabulary, without subsuming it into sameness? I am arguing that this is precisely what earth artists attempt by creating works that are both bound up in a site but which problematize the sensation of its natural activity as tangible substance. The artwork may be integrated in a site but it turns to face that site as well, offering a surface from within its elemental substance, on which the earth appears without being formalized into a fixed image or object. Here, it would be useful to suggest that in earth art, elemental substance mediates sensation, but the earth itself never coalesces into a defined entity. It defies representation, appearing instead as disorderly manifestations within the elemental; the volatile reflections in Drury's Wave Chamber, or the tide that contorts the silueta in Mendieta's Untitled (1976) performance.

Figure 4. Ana Mendieta. Incantation a Olokun-Yemayá , black and white photograph, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1977. © Estate of Ana Mendieta, courtesy of the Galerie Lelong, New York.

<26> In another silueta work executed in Oaxaca, Mexico in 1977, Mendieta elaborates what I am describing as a 'facing' of the earth. She pictures an exchange of tactile contact called forth by the earth and reciprocated by body. For Incantation a Olokun-Yemayá (Figure 5), the artist impressed her body inside the outline of a giant hand. The focus of this work is not the disfiguration of the imprint - it wasn't photographed in a sequence as a temporal performance. The key is the division between the body's surface and the earth's surface, and the figuration of that contact as an act of touching and being touched. The hand, created by piling sand along its outline, is not pushed into the land from above as though to allegorize the artist's hand. Rather it gives the illusion that the edges of the hand are pushing out from an unseen subterranean force. Further, it appears in tension with the body's shape that is pressed into it. Mendieta emphasized the sense of pressure by setting the head of the imprint in the opposite direction of the fingers. The hand does not frame the imprinted body; it is situated across from it, the head at the inverse of the finger into which it is laid. Significantly, the hand does not close around the silueta; it remains open against the body's surface, receiving the imprint but not absorbing it. Mendieta thus disarticulates the body and the earth by placing them in a sensorial relation to one another.

<27> The earth's face appears in the tactile relation that sustains division, precisely because of the resistance between the land and the body. Incantation allegorizes this sensorial encounter: the body pushes against the hand and the hand in turn receives, neither grasping nor enfolding. Mendieta pictures the body-earth contact as pressure against, akin to the tactile relation of the two hands pressed together that Irigaray proposes in response to Merleau-Ponty. In asserting the contact between the body and the earth as a gesture of facing, the artist aligns the aesthetic dimension of the artwork with an ethical imperative.

Jackie Brookner's Prima Lingua: The Earth Beyond Articulation

<28> The ethical crux of Drury and Mendieta's art lies in their negotiation of a sensorial relation with the earth, whereby natural processes flourish without being reduced to a human-centered framework. In theorizing the body-earth relation as a facing of the earth, I am suggesting that their works raise an aesthetic problem as well as a new ethical paradigm. If the earth's sensorial excess cannot be represented or thematized as such, artists must confront the issue of how to evoke sensation without articulating the earth as an entity that is known or knowable to us. In her work Prima Lingua (Figures 6 and 7), the American eco-artist Jackie Brookner foregrounds precisely this tension between sensing the earth and expressing its 'inarticulability'. Since the early eighties, Brookner has been producing sculptures and site-restoration projects that highlight ecological regeneration. She designs living sculptures, called "biosculptures", which are plant-based systems that clean polluted water. [29]

<29> Like many of Brookner's works, Prima Lingua is a biosculpture, an object engineered by the artist to function as a water filtration system. Brookner's biosculptures are made of stone, rock or concrete, materials on which mosses, liverworts, ferns and other plants and snails can proliferate. The artist explains that the sculpture is a biogeochemical filter: as water flows over it, plants, bacterium and other organisms turn pollutants into sustaining nutrients. [30] The mosses absorb toxins and even heavy metals, while the porous concrete substructure removes larger particulates and debris. Prima Lingua, a biosculpture made in the shape of a giant tongue, stands in what began as a pool of polluted water. Between 1996 and 2001, Brookner pumped the water over the surface of the tongue, and over time vegetation grew and thickened on the sculpture, gradually purifying the pool.

<30> It is significant that Brookner chose a tongue as the sculptural motif. The artist describes the tongue as literally licking the water in which it stands; indeed, the pouring water calls to mind dripping saliva. There are several particularities to the tongue that convey the relation between the sculpture, the water and the subsequent growth of vegetation. In foregrounding the role of the tongue to lick the water clean, Brookner invokes a specific mode of sensorial experience that cannot be expressed by any other body part. The act of licking involves two senses: touching and tasting. Tongues feel contour and texture, sensing through tactile exploration; however, they need only be passively applied as a surface to glean a sense of taste. Tasting, in contrast to the possible intentionality of touching, is a matter of receiving flavor. The aesthetic richness of Prima Lingua is not merely hinged on the tongue as a sculptural object or on the vegetation in and of itself, but on the particular way the tongue cues the experience of the vegetation -

allowing it to blossom uninterrupted by a penetrating touch. Not coincidentally, it stands vertically, pushed flat and wide rather than sticking out horizontally into the gallery space. The sculptured tongue seemingly offers itself as a surface to the lively growth of mosses and plants, and presents them to the spectator as though they were a burst of flavor.

Figure 5. Jackie Brookner, Prima Lingua, biosculpture made of concrete, volcanic rock, steel, mosses, ferns, wetland plants, fish, water, 1996, mosses beginning to grow - profile. © Jackie Brookner.

Figure 6. Jackie Brookner, Prima Lingua, 2001 - mosses and ferns grown in. © Jackie Brookner.

<31> This flourishing of growth, however, is also analogous to a form of language. Yet where in a dualistic logic the discursive realm (the realm of language and speech) is often considered to be separate from and superior to the terrestrial sphere of nature, Brookner secures their inextricability. Here, the growth, fruition and decay of vegetation substitute human language, or as Brookner suggests in the title 'Prima Lingua', they are a pre-linguistic communication. The continuous pouring of water over the tongue stimulates the emergence, not of defined words but of what we might call vegetal utterances that rise up and fall away. Despite the artist's insistence on the primacy of nature's expressiveness, the artwork does not propose a primal or fundamental knowledge of the earth. The sculpture supports because it is a surface turned against the growth. The tongue offers itself as a fleshy division; it does not close around the vegetation to form a word, assembling it into human meaning, but rather sustains the earth's proliferation by remaining open against its unintelligibility.

<32> Like Drury and Mendieta, Brookner deploys her art as a vehicle to stimulate the earth's manifestation, and to evoke a sensation of it in the contact between two surfaces as, in Irigaray's words, 'two lips gathered at the edge of speech'. Brookner posits a facing of the earth as this moment of pause before articulation. Sensing the earth, here, is predicated on remaining open to, and against, its subtle expressiveness. In turning an intentional act of speech into a receptive process of taste, the artist shows the influx of sensations of the earth that precede, and most importantly that exceed, discursive meaning. The artwork thus figures communication between the body and the earth as reciprocal touch; the earth appears because of the tongue's passive supply of contact. The earth's appearance is open-ended; it blooms but is never secured as a closed object to be held or seen in the grip of Merleau-Pontian perception. The continual transformation of the system forecloses the principle that sensation will lead to a defined perception, or an intelligible representation.

Conclusion

<33> In the nineteen-sixties, the earthworks movement challenged the view that cultural practices could be separated from their basis in the earth. More than simply using natural materials, earth artists integrated their artworks into the landscape to draw attention to the earth's processes beyond the parameters of human experience. Since the nineteen-seventies, however, contemporary earth artists have been developing the ethical framework of these interventions, and have in fact counteracted the romantic paradigm in which the earthwork is understood to mediate an immersive experience of the earth. I have argued that by contrast to early earthworks, contemporary earth artists orient their practices towards identifying the point at which the earth exceeds our capacity to perceive it as a totality. The artworks I have discussed thwart an immersive scenario, and instead articulate the threshold of encounter between the body and the earth. This threshold is both the point of physical contact, and the point at which we sense the earth's alien presence.

<34> Through the friction of encountering the limits of our perceptual expectations, and a sense of the earth's excess beyond those limits, Drury, Mendieta and Brookner align their aesthetic project with an ethical acknowledgment of the earth's alterity. The result is an abundance of dispersed sensation: transient expressions such as the influx of light and color, spectral shapes, and flourishing growth, all of which foreclose the possibility of coalescing the earth into a totalized representation. Rather than seeking immersion in the earth, then, contemporary artists create spaces to, in Mick Smith' s words, "let nature be, allowing it to manifest itself within life and language in all its uncomfortable difference thus, "permitting union through resistance to assimilation. [31]

Notes

[1] See Rosalind Krauss, Passages in Modern Sculpture (New York: The Viking Press, 1977). [^]

[2] Though as Amelia Jones has rightly argued in her book Body Art: Performing the Subject (1998), abstract expressionist painters (and notably, Jackson Pollock) initiated an embodied artistic practice that is inextricable from the art object itself. [^]

[3] See Rosalind Krauss, "Richard Serra: Sculpture," Richard Serra eds. Hal Foster and Gordon Hughes (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000). [^]

[4] Richard Serra, quoted in Krauss, Richard Serra, 128. [^]

[5] Richard Serra, quoted in Krauss, Richard Serra, 129. [^]

[6] Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (1945) trans. Colin Smith ( New York: Routledge, 2002) 352-353. [^]

[7] See for example Alex Potts, "Tactility: The Interrogation of Medium in Art of the 1960s," Art History 27 no. 2 (April 2004) 282-304; and Amelia Jones Body Art: Performing the Subject (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998). [^]

[8] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible (1964) trans. Alphonso Lingis, ed. Claude Lefort (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1968) 130. [^]

[9] See Luce Irigaray, An Ethics of Sexual Difference , trans. Carolyn Burke and Gillian C. Gill, (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1993). [^]

[10] Irigaray, An Ethics of Sexual Difference, 173. [^]

[11] Irigaray, An Ethics of Sexual Difference, 183. [^]

[12] Mick Smith, An Ethics of Place: Radical Ecology, Postmodernity, and Social Theory ( Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001) 171. [^]

[13] Drury was born in Sri Lanka, and trained in sculpture at the Camberwell School of Art in Britain. His artworks deal with the human relationship to nature, and often involve his excursions into remote landscapes. His most recent work deals with the connection between ecosystems and the systems of the human body. For more information on Drury's works, please see Chris Drury, Found Moments in Time and Space (New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc, 1998), and the artist's website at www.chrisdrury.co.uk. [^]

[14] Chris Drury, Found Moments in Time and Space (New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc, 1998) 20. [^]

[15] Drury,117. [^]

[16] See Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991). [^]

[17] Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisibile, 133. [^]

[18] Mendieta was born in Cuba and exiled to the United States at the age of twelve. She trained as an artist at the University of Iowa. She began her Silueta Series in 1974 and executed most of these performances in Iowa and Mexico. Mendieta eventually moved to New York where she became well-known as a feminist performance artist. Sadly, in 1985 Mendieta died at the age of 36. [^]

[19] Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994) 105. [^]

[20] Irigaray, An Ethics of Sexual Difference, 182-183. [^]

[21] Grosz, 105. [^]

[22] Irigaray, An Ethics of SexualDifference, 161. [^]

[23] Irigaray, An Ethics of Sexual Difference, 161. [^]

[24] Tina Chanter, Ethics of Eros: Irigaray's Rewriting of the Philosophers (New York: Routledge, 1995) 222. [^]

[25] Smith, 181. [^]

[26] Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, trans. Alphonso Lingis, (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1969) 50-51. [^]

[27] Alphonso Lingis, The Community of Those Who Have Nothing in Common(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994) 122. [^]

[28] Lingis, Sensation: Intelligibility in Sensibility (New Jersey: Humanities Press, 1996) 101. [^]

[29] Now based in New York, Brookner works in collaboration with ecologists, policy-makers and communities to make public site-restoration works in North America and Europe. Her sculptures generally involve water remediation for wetlands, rivers, streams and stormwater runoff. For more information please see www.jackiebrookner.net. [^]

[30] http://www.jackiebrookner.net/Biosculptures_files/Biosculptures.htm [^]

[31] Smith, 188. [^]

Return to Top»