Reconstruction 7.2 (2007)

Return to Contents»

Thinking Like a God: Nature Imagery in Advertising / Catherine M. Roach

Abstract: This essay examines selected recent imagery from American advertising that evinces a "negative" sense of nature as hostile other - often portrayed as a persecuting and conquered female - and of humans as its/her master. Examples to be examined of nature as this "Bad Mother" include TV commercials, print advertisements, and a comic strip. I argue that these images spring from a fundamental ambivalence toward nature and that they assuage the anxiety aroused by such ambivalence through a fantasy that casts humans as gods. More specifically, I use the medieval Christian scholastic concept of 'aseity' to suggest that these media images co-opt for humans the perceived independence, or aseity, posited by theologians as one of the characteristics of God.

<1> Thunder crashes, and lightning forks the sky. A car drives in a pelting rainstorm, sloshing through thick mud on a soaked and rutted road. Quick shots of crashing waves and lashing rains follow, as an unseen woman intones, in a deep and throaty voice: "She will try to drown you." The car still drives, in the midst now of a blizzard of snow and ice. Deep drifts block its path, but the car plows through. The woman's voice warns: "She will try to freeze you." Scenes flash of a blistering sun and a parched landscape. The car, looking hazy through the heat, speeds along the scorched, cracked earth. Same voice: "She will try to burn you." A hurricane now rages. Fierce winds whip at the car and push it diagonally across the road: "She will try to blow you away." Finally, the weather clears. The car drives down a rugged highway in a mountain setting. It leaps over a rise in the road - jumping for joy? Defiant even of nature's law of gravity? - and the voice triumphantly exults: "But she will not succeed." The car lands safely to ride off into a mountain pass, having survived it all, pristine and unharmed. The woman then announces the name of the victor in this life-or-death battle, like the winner at the end of a boxing match: "The Nissan Pathfinder."

<2> This scenario played out repeatedly on television in the fall of 1994. It is a thirty-second commercial for the sport-utility vehicle made by Nissan called the Pathfinder. What do such media images tell us about how nature is understood and valued in contemporary America? What insight do they give into the task of building environmentally sustainable and socially just communities in the twenty-first century? Does an analysis informed by popular culture studies, ecotheology, and ecofeminism help answer these questions? The control of nature - or to go further, the domination of nature as subdued adversary - can be a powerful and attractive fantasy. It is the fantasy of freedom from the limitation, vulnerability, and ultimately death entailed by our human status as beings-in-nature. We are, not unreasonably, ambivalent about this status. This ambivalence encompasses heartfelt desires to be free from an enemy feared and disdained, as well as equally sincere desires to mend and preserve a beloved home.

<3> This essay examines selected recent imagery from American advertising that evinces this "negative" sense of nature as hostile other - often portrayed as a persecuting and conquered female - and of humans as its/her master. Nature here is the Bad Mother, although she appears in popular culture just as frequently in two other motifs not examined in this essay: the Good Mother (nurturing, benevolent, loving) and the Hurt Mother (wounded through human misuse and now the focus of our guilt-ridden and heartfelt efforts at repair). [1] Examples of hostile nature to be examined here include TV commercials, print advertisements, and a comic strip. I argue that these images spring from a fundamental ambivalence toward nature and that they assuage the anxiety aroused by such ambivalence through a fantasy that casts humans as gods. More specifically, I use the medieval Christian scholastic concept of 'aseity' to suggest that these media images co-opt for humans the perceived independence, or aseity, posited by Christian theologians as one of the characteristics of God.

<4> Coleridge, the nineteenth-century English Romantic poet, referred to aseity not unfairly as an "obscure and abysmal subject." The term derives from the Latin "a se," meaning "from oneself." Aseity describes the nature of the Western monotheistic God as self-derived or self-originated; God is claimed to be without dependence on any other being, either for God's origination or continuing existence. Were the world to blow up tomorrow in a giant asteroid smash, God would not be harmed or changed. The doctrine of aseity thus refers to God's absolute self-sufficiency, autonomy, and independence from the creation. [2] While invoking the language of Christian theology may seem a strange move for contemporary media analysis and green cultural studies, I find the concept of aseity remarkably useful as a tool for probing the motivation or fantasy behind the media images studied in this essay, namely an ambivalence toward nature and an anxious desire for godlike independence from it. Such media imagery bears careful examination, as it speaks to common and widespread ways of understanding nature and to the challenges of environmentalism in the twenty-first century.

* * *

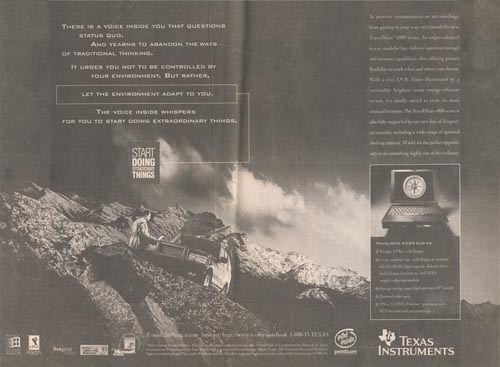

<5> Two recent newspaper advertisements illustrate this ambivalence. The first ad, for Texas Instruments, pictures a man standing beside his truck with a laptop computer open on the hood (see Figure 1). The truck is precariously parked, clinging to a rocky mountain face, yet the man works calmly, confidently. The text reads:

There is a voice inside you that questions status quo.

And yearns to abandon the ways of traditional thinking.

It urges you not to be controlled by your environment. But rather, let the environment adapt to you.

The voice inside whispers for you to start doing extraordinary things.

Figure 1. "Let the environment adapt to you." Texas Instruments print advertisement. Appeared in The Wall Street Journal, 1996.

[click image for larger version]

In another ad, this time one for General Motors, a man gallops bareback on a horse across an open desert, clutching a briefcase (see Figure 2). Beside them is written:

It's 1894. You've got a job interview. Tomorrow. 140 miles away. Giddyup.

There was a time when people couldn't chase their dreams any further than a good horse could carry them.

When men and women who wanted to see the world spent days just getting to the next town.

Driving changed all that.

It frees us from the constraints of place. We go where we want, when we want. And if we hit a red light, we know more surely than we know most things in life, it will soon turn green.

Figure 2. "Giddyup." General Motors print advertisement. Appeared in The Wall Street Journal, 1996.

[click image for larger version]

These ads reveal a deep, perhaps only semiconscious, ambivalence toward nature. They complain about "the constraints of place" and rebelliously, arrogantly, urge you to "let the environment adapt to you." Yet their photography celebrates the beauty of nature, the endless open vistas of mountain and desert, the power and speed of a galloping horse - ridden without bridle or saddle. These are all used as images of freedom. Most fundamentally, then, the ads seem to reveal an envy of nature. Nature both represents and withholds freedom. The ads promise that technology grants both freedom from nature and the freedom of nature. They illustrate how we rely upon technology to deny the limits that we perceive nature to impose upon us. At the same time, technology is to provide us with the limitlessness - the openness of possibility, the room to maneuver - that we perceive as inherent to these wilderness landscapes. This love/hate relationship has us admiring and celebrating nature, while at the same time deriding and rejecting it.

<6> We start to see the connection between ambivalence and the fantasy that technology will allow escape or mastery over the natural constraints that provoke the ambivalence. Let me illustrate further through analysis of a newspaper cartoon strip: The cartoon shows a man watching a television broadcast as it reports: "Worldwatch Institute says we need to stop consuming the planet immediately. Or we lose it. It's as simple as that." After a frame of silent reflection, we get the punch line of the cartoon. A balloon appears over the man, who hasn't moved: "Decisions, decisions," he thinks. A tiny cartoon-within-a-cartoon is tucked into the bottom of this last frame. It represents, perhaps, "the little voice inside our head" and a deeper, second level of response, less conscious and acknowledged than the first. Here, still slouched in his armchair by the TV, he asks: "How much longer am I, personally, going to need it?"

<7> The cartoonist, Tom Toles, no doubt created the strip to mock such arrogant self-centeredness. In so doing, he might arguably be exaggerating his portrayal of modern man, master of technology, as only marginally concerned about ecological collapse and half-convinced it will not affect him. Yet environmental theorists tell us this portrait is not so far off. While the attitude seems callous, I think it masks an even deeper third level of response, this one full of feeling - and of fear. Here, the callousness is bravado that covers up and wards off - but also betrays - an underlying anxiety of helplessness and despair. Thus the most hidden, unspoken response in the cartoon is either: "How much longer am I going to live (in this increasingly poisoned world)?" or "How soon will technology allow me to live without it?" in the fantasy of escape from nature or of complete mastery over it.

<8> In the language of Christian theology, this fantasy is one of aseity. By using this concept as an analytical tool to help understand the media images, we see that not only do the images portray ambivalence about nature, and not only do they use technology to assuage the anxiety of this ambivalence, but also that these advertisements and cartoon seek to resolve the ambivalence by casting humans as godlike beings, independent of their environment. The media imagery I highlight co-opts for humans the perceived aseity of God. The imagery incorporates assumptions of God's power over nature and freedom from nature, both granted here to humans. The advertisement's, in short, make us godlike.

<9> This point returns us to the Nissan commercial since the Pathfinder displays, I suggest, a quality not unlike this aseity of God. The commercial's fascinating language and imagery tell us at least three things. First, nature is female and mother. Although the term "Mother Nature" is never used in the commercial, that is the advertisement's name, as I discovered when the people at Nissan kindly sent me a video copy of the advertisement. Even without knowing the official name, audiences have little or no trouble identifying the "she" of the text as Mother Nature. Second, this female intends us grave harm; nature is cruel and torturous as she attempts to drown, freeze, burn, and blow us away. The environmental movement rarely invokes this picture of nature as hostile female adversary or Bad Mother, but it exists nonetheless. The wellspring of imagery and emotion that feeds the mother-nature association is loving in reference to the Good Mother, as in the well-known environmental slogan "Love Your Mother" that urges us to care for the nurturing planet. But the imagery and emotion are also aggressive in relation to the persecuting mother, as in this bold Nissan commercial. Environmental criticism needs to pay more attention to nature as Bad Mother, for the motif is surprisingly common in popular culture and is indicative of the aggression, resentment, and rebellion felt against both nature cast as mother and woman cast as natural (or less than fully human). Third, nature's threat can be neutralized so that humans emerge unscathed. Such control and ultimate conquest of nature come about through the power of human technology - here in the form of the Pathfinder - that grants us god-like independence from the grip of natural creation. If indeed technology makes us gods, we need no longer chafe under the limits of nature nor fear destruction from her threat. From Nissan's point of view, of course, the purpose of the advertisement is to suggest that the Pathfinder does the job with particular finesse and that viewers would be well served by buying one soon.

<10> With images like this commercial, we may well start to wonder whether there is an "or else" implicit in that famous environmental slogan "Love Your Mother." Love your mother, the Nissan images suggest, or else she will turn on you, get you, hurt you. Be nice to your mother to ensure that you are protected against her mean and persecuting side. Scientist James Lovelock, in his writing about the Gaia hypothesis - i.e., the notion that the planet is in many ways a self-regulating organism that he metaphorically names Gaia - puts it this way: Gaia is "stern and tough, always keeping the world warm and comfortable for those who obey her rules, but ruthless in her destruction of those who transgress." [3] Nature here is capricious and fitful, easily transformed from beloved and loving, into hated and hateful.

<11> One emotion that animates this Nissan commercial is fear, not only of nature, but also of the mother's rage, or of the anger in general of a woman who has been crossed. The commercial implies that the recipe for neutralizing this dangerous fit of pique is sexualized control by the male over the unruly female. Thus the hand that viewers see on the car's steering wheel - our only glimpse of human presence - is solidly male. The female narrator's voice is a sultry purr, devoid of anger, hinting that she, at least, has been tamed. Her exultant tone on her last line, "But she will not succeed," reassures that this female is not united in sisterhood with Mother Nature but is on the side of the viewer, of the human, of the male. The intended implication seems to be that all females - including the one currently launching the attack - can and will soon be brought under control.

<12> Indeed, I suspect that the narrator of this commercial has to be female in order for the advertisement to convince its audience that rampageous females, and Mother Nature in particular, can be controlled and that the Pathfinder is just the thing to do the job right. The commercial has a subtext of sexual conquest, emphasized by the quite sexy background music in which the singer's wordless vocals could just as easily be described as moans. Male conquers female - or turns her howls of rage into purring pleasure; culture, cast as male, conquers nature, cast as female. Women viewers can participate in this fantasy equally well, either agreeing that the mother's rage needs to be tamed (as children themselves of sometimes scary mothers) or identifying with the satiated, well-pleased woman who has accepted her place in the male-ordered world.

<13> I wonder here about the possibility of a fourth motif: that of the Sexual Mother. Generally, in Mother Nature imagery, the mother's sexuality is a buried theme, represented only indirectly through her fertility. She is rarely presented as directly sexual (e.g., flirtatious, seductive, desirous, sated) but is often pictured as fertile and fecund, as powerful because of her reproductive ability to create new life. Her sexuality, in other words, is not something that serves for either her own pleasure or that of any imagined partner; Mother Nature seems not to be a sexual being in that way. This holds true for the Nissan advertisement, except for the sensuality of the narrator's sultry voice and the moaning background vocals - both female. Neither are directly associated with Mother Nature, but they do set a certain sensual tone for the commercial. [4]

<14> The aseity or independence fantasized in the advertisement comes about through technology that protects us from nature's rages, but it can also derive from technology that allows us to make our own products of nature, better than can Mother Nature herself. This theme is the imagistic heart of one of the most popular American advertising campaigns in recent decades. Chiffon Margarine used the slogan "It's not nice to fool Mother Nature" to suggest that their margarine tastes so much like butter that Nature herself would be fooled (see Figure 3). A thirty-second commercial built around this slogan aired in 1977. It opens with a woman, "Mother Nature," seated in a rocking chair and recounting the fairy tale of Goldilocks to a group of animals (a raccoon, deer, and cougar). She is middle-aged, attractive in a matronly way, dressed in flowing white robes, and has a crown of daisies in her short dark hair.

Figure 3."It's not nice to fool Mother Nature." Still from Chiffon margarine television commercial, 1977.

[click image for larger version]

Mother Nature: Then Goldilocks said, "Who's been eating my porridge?"

A male voiceover, cheery and affectionate, interrupts her.

Voiceover : Mother Nature, was this on the porridge?

Mother Nature : [She tastes from a tub offered by an unseen hand.]

Yes, lots of my delicious butter.

Voiceover : That's Chiffon margarine, not butter.

Mother Nature : Margarine! Oh, no! It's too sweet, too creamy!

Voiceover : Chiffon's so delicious, it fooled even you, Mother Nature.

Mother Nature : Oh, it's not nice to fool Mother Nature!

On the last two words, her voice drops from its previous loving tones into a deep and angry register. She stands up and casts her arms wide, unleashing peals of thunder and flashes of lightning. We see the raccoon hide its eyes behind its paws. The closing jingle then plays over an image of the margarine package in front of leafy branches blowing in a gentle breeze: "If you think it's butter but it's not, it's Chiffon!"

<15> The phrase "It's not nice to fool Mother Nature" implies not only that humans can fool nature by making a "butter" as good as hers, but also that nature is hurt or angered by being made such a fool. Human attempts to imitate or improve upon her bounty may well rouse her displeasure, signaled at the end of the commercial - as in the case of the Pathfinder - through peals of thunder and flashes of lightning. By the 1980's, "It's not nice to fool Mother Nature" had become one of the most recognized commercial lines, and it remains so today, often no longer even connected in people's minds with Chiffon Margarine. Clearly, this imagery has broad resonance, or what the advertising industry calls "associative appeal." [5]

<16> The commercial, however, is more ambiguous than the Nissan advertisement, for it is not clear how a tub of margarine can control the rampage of nature it might provoke, unlike the Pathfinder which seems able to handle anything. In the Chiffon advertisement, humans seem to get away with their foolery, like naughty children caught in a prank as mother's expense that makes her bluster but is not wicked enough to incite real punishment. The commercial's mood is light-hearted and comical, and it contains the threat it evokes of nature's destructive power by limiting signs of ire to those few seconds of atmospheric disturbance. The imagery of the final shot, as the jingle plays, immediately reassures us that mother is not really angry, that she was only bluffing, that she has already gotten over her pique. In this last image, the befooling trickster margarine sits securely in the forefront, and nature is once again a peaceful background of swaying branches, as on a warm summer day.

<17> The packaging of the margarine in this last shot features prominent pictures of daisies. They are the same daisies, in fact, that Mother Nature wore in her hair. Chiffon thus naughtily dupes Mother Nature not only into thinking the margarine is butter, but also into unwittingly becoming spokeswoman and symbol for the product that itself adopts, or co-opts, her symbols. Here is the paradox - by no means uncommon - of a product of human technology purposefully manufactured and marketed to appear as natural as possible. Thus in another take on the aseity fantasy, we seek to free ourselves from implication in nature through products of technology designed to imitate but supersede their natural counterparts, i.e., the artificial designed to appear natural. Twenty-five years after the advertisement first appeared, the technologies that now make possible genetically modified organisms (GMOs), both plant and animal, carry the promise even further.

<18> The Nissan advertisement takes the ambiguity of its predecessor in the opposite direction. Here the mood is epic or even tragic, although ultimately triumphant. Nature is fully realized as the dangerous killer only hinted at in Chiffon's portrayal. Considering the two commercials together raises the possibility that Mother Nature is so angry in the Nissan advertisement precisely because of the indignities she has had to suffer, as in the Chiffon advertisement. Has a change occurred in the cultural imagination such that we no longer expect Mother Nature to let us off lightly? Do we now fear our environmental abuse gives her good cause to punish us and seek her revenge?

<19> In this reading, anxiety over nature's retaliation - a danger perceived comically in Chiffon's commercial - fuels the fantasy of aseity. The genre changes from comedy to tragedy, and we end up with a vision of escalating warfare between humans and nature. Every time we challenge or best or wound her, her wrath is roused to a fiercer pitch that impels us to invent new technological superiority, such as the Pathfinder, to subdue nature's enmity and free us from her reach. Running all the slogans together then produces a simplistic narrative: "Love your mother/Mother Nature, but don't try to fool her, lest she then try to drown you. She will not succeed, however, if the right technology of armor and weaponry removes you from her realm." It sounds like the plot of a fairy tale or action-adventure movie, but is, quite literally, one popular way of casting human-nature relations.

<20> Another of the major auto manufacturers confirms this trend. (As an aside, it is interesting to note how auto companies seem leading players, indeed self-cast warriors, in the battle against nature. Their advertisements do not hesitate to give free rein to the fear and anger behind the aseity fantasy. One may speculate here about the special role of the car in American myth, as the vehicle par excellence of the individualistic freedom so central to that myth.) Chevrolet based a 1996 promotion on a transformation of the "Love Your Mother" poster (see Figure 4). A full-color newspaper advertisement pictures the Chevy Blazer, a sport-utility vehicle similar to the Pathfinder, aglow in handsome profile. Next to it is a slogan that reads like reassurance of safety and promise of retaliation against an unruly other whose bad temper we have too long endured. "Control your Mother," it says, in both offer and order. Smaller copy elaborates. The Blazer "helps you control just about anything Mother Nature throws your way." This is the perfect revenge fantasy in which we get back at nature for her annihilative attempts at our murder, her punitive attempts at our control. The victorious technology of Pathfinder and Blazer makes us feel strong and adult and reassures with its satisfying promise to conquer nature in any of her rampageous moods.

Figure 4."Control your Mother." Chevy Blazer print advertisement. Appeared in USA Today, 1996.

[click image for larger version]

<21> One final advertisement leads us to the inevitable culmination of this trend and provides the strongest evidence for the aseity fantasy. Given the analysis so far, it should come as no surprise that auto companies actually promote the association of their product with the divine. In a splendid example of sport-utility vehicle advertising, Toyota sets this slogan above a shot of their Land Cruiser parked in a southwestern desert setting (see Figure 5): In primitive times, it would've been a god. The advertisement's copy explains that the Land Cruiser "has the qualities man has revered and respected for thousands of years. The power to tame the forces of nature. The prowess to navigate almost any terrain . . . . an interior so roomy, it can inspire awe in up to seven adults at once. . . . For us mortals, it's the ultimate." In very small print at the bottom - along with contact information (1-800-GO-TOYOTA) and a warning to always buckle up - is a nod to environmentalists and property owners: " Toyota reminds you to Tread Lightly! on public and private land." How reassuring that while the Land Cruiser has the power to tame the forces of nature, it will proceed with caution while doing so! We see here the conflicted response to nature: conquer it, but protect it at the same time. Toyota's slogan in the bottom right completes the advertisement's triumphant and self-satisfied tone: "I love what you do for me." While the advertisement modestly (or ironically) still calls us "mortals," since it is we who have created the divine Land Cruiser, we may rightfully infer our own status as divine. In the twenty-first century, humans and car together have attained the godly ability to tame nature, at least in the imaginative world of the advertisement. The advertisement worships the technology that allows us to fantasize our own godlike independence from nature.

Figure 5. "In primitive times, it would've been a god." Toyota Land Cruiser print advertisement. Appeared in Bon Appétit magazine, 1997.

[click image for larger version]

<22> This fantasy of aseity, in conclusion, springs from an ambivalence that is partly justified (to the extent that natural disasters do kill and that nature reminds us of our vulnerability and mortality) but is also largely exaggerated. We exaggerate this ambivalence and fantasize our aseity out of fear of mortality; out of envy of nature's goods (openness, power, beauty); out of resentment at being made to feel helpless, imperiled, infantalized, and bested; and in retaliation for a sense of Mother Nature as unresponsive to our infantile wishes for an inexhaustible source of care and love, there just for us. Where does this analysis leave us in terms of an eco-critical reading of trends and challenges in contemporary American society? While we may hope that we are heading toward a future of more environmentally sustainable living, advertising - especially in the United States, the world's capital of consumption - features imagery still deeply ambivalent.

<23> From the cultural point of view of environmentalism, the freedom fantasy of aseity is clearly a dangerous one. It works against ecological knowledge that nature does not exist to cater to human desire and that we are in fact deeply dependent on the health of the environment for our own healthful existence. The fantasy constitutes a violation of ecological knowledge about the integrity and interrelation of all parts of the global ecosystem. Undermined also by the fantasy is any motivation for environmental protection, for who aids an adversary bent on their destruction?

<24> From the ecotheological perspective, the fantasy of aseity is equally suspect. In traditional Christian terms, it would render those who succumb to it guilty of the sin of pride. By claiming one of God's qualities for humans or for the products of human technology, people in effect claim divinity. Theologians find this problematic for exactly the same reason as do environmentalists: it entails a denial of human finitude, of our physicality and embodiment; it claims that humans in this world are to enjoy godlike exemption from the natural constraints of life and death. The fantasy of aseity ends up as an idolatry of technology deeply worrisome to theologian and environmentalist alike.

25> Finally, from the point of view of media studies, we see how a critique of advertising permits unique insight into the aseity fantasy. Corporate marketing departments and their advertising agencies invest millions of dollars in careful research to ensure their advertisement campaigns have the broadest appeal. Advertising is thus a particularly telling forum precisely because it is designed to connect with very widespread popular feelings, anxieties, and desires. These advertisements reflect people's attitudes about nature, but also then shape our attitudes in ways that strike me as problematic. Communications scholars tell us that the average North American person now spends nineyears of his or her life watching television and that we are subjected daily to 3600 "consumer impressions," or advertising appeals to us as people with money to spend. [6] This advertising culture is an important study ground for environmental criticism, not only because so many of the advertisements draw on natural images, but also since the underlying message is that happiness comes through endless consumption of goods, ecological degradation be damned. My method has been to read these advertisements as a valuable text of largely semiconscious, unarticulated, but nevertheless widely held feelings about nature, feelings whose study is key to our survival.

References

Jhally, Sut. "Advertising and the End of the World," video cassette. Northampton, Mass.: Media Education Foundation, 1998.

-----. "Advertising at the Edge of the Apocalypse." Article Online. No date. <www.sutjhally.com> Accessed September 2002.

Lovelock, James. The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth. New York: Bantam Books, 1990.

Merchant, Carolyn. The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1980.

Solomon, Marc. "A Few Choice Words: Ad Slogans in the Popular Media, 1980-1990." Winter 1996, on the web site of LKM Research, Inc. <http://hamp.hampshire.edu/~eprF94/LKMsample.html>

Notes

[1] Those readers seeking a more detailed analysis of the relation among these motifs portraying nature as Good/Bad/Hurt Mother may be interested in the larger book project from which this essay is drawn: Catherine M. Roach, Mother / Nature: Popular Culture and Environmental Ethics (Indiana University Press, 2003). [^]

[2] Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Aids to Reflection, 1848, I:270, quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary (1933); definitions for "aseity" also consulted from Webster's Third New International Dictionary, the Random House Dictionary of the English Language, and the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Religion. [^]

[3] Lovelock 1990: 212. [^]

[4] One of the only outright sexual representations I have come across of Mother Nature is a sculpture entitled Nature reveals Itself by Louis-Ernest Barrias (French, 1841-1905; reproduced in Merchant 1980: 191). We see here nature as a beautiful young woman, her breasts bare, in the act of seductively lifting her veil to reveal still more of herself to her implied partner of science. This motif of the Sexual Mother merits further study, as does its relation to nature as Bad Mother. Barrias's Nature, for example, reveals herself in a way no "good" woman ever would. Sexuality traditionally bears a negative valence in Western culture as a morally dangerous force tending toward the distraction, if not outright corruption, of the soul, and women pose special dangers here as temptresses of men. [^]

[5] Solomon 1996: 8. [^]

[6] Jhally, "Advertising and the End of the World" and "Advertising at the Edge of the Apocalypse." For environmentally-informed critique of media and advertising, see Ad Busters (http://adbusters.org) and the Media Education Foundation (http://www.mediaed.org), which produces excellent videos on the subject. [^]

Return to Top»