Reconstruction 9.1 (2009)

Return to Contents>>

The Memory Archive: Filmic Collaborations in Art and Anthropology / Alyssa Grossman and Selena Kimball

Abstract: This paper forms the space for dialogue between a social anthropologist (Grossman) and a visual artist (Kimball), who have been collaborating on installations and films throughout the past decade. Our most recent films, including Into the Field (2005), and Objects of Memory (in progress) are shot on location in Grossman’s fieldwork sites in Romania, and incorporate sequences of stop-motion animation by Kimball. These films explore and question the conventional boundaries between art and anthropology.In this article, we examine the process of filming collaboratively in the field, and discuss the challenges and transformations we each undergo through sharing the literal and theoretical spaces of anthropological fieldwork and artistic production. We also examine the ways in which our individual approaches to cultural investigation both diverge and overlap, deeply influencing our individual work within our own respective disciplines.

I feel sorry for those who have not, at least once in their lives, dreamt of turning into one or other of the nondescript objects that surround them: a table, a chair, an animal, a tree trunk, a sheet of paper…

–Michel Leiris, "Dictionaire critique: Metamorphosis," Documents 6 (November 1 9).[1]

Introduction

<1> This paper explores the dimensions and dynamics of the relationship between its co-authors, an artist and an anthropologist, focusing on a recent collaborative project occurring within the context of the anthropologist's ethnographic fieldwork. We discuss the development of this particular collaboration, which involves a treatment of material artifacts through the medium of film, and detail the challenges and transformations both of us have undergone through sharing the literal and theoretical spaces of anthropological and artistic work. Stimulated and encouraged by the recent spate of literature surrounding "new dialogues" and "shared strategies" between the disciplines of art and anthropology (cf. Schneider and Wright 2006; Grimshaw and Ravetz 2004), we are now beginning to critically examine their relevance to our own collaborative experience of being and working "in the field."

<2> Through our collaboration we aim to actively define a new space between art and anthropology having foundations in both disciplines, but without one serving as an auxiliary to the other. We maintain that the use of the visual in anthropology can exist beyond the category of a "sub-discipline," by utilizing creative and experimental fieldwork methodologies consisting of engaged and embodied practices, and by playfully interrogating, as well as documenting and explaining material culture. We also argue that an artist can engage with anthropological theory and debates at multiple stages of his or her art practice, through making the "field" an extension of the "studio," a place where ethnographic awareness can inform and shape the creative process. Although we employ methods of interdisciplinary "appropriation," [2] and influence each other to question and revise our own background assumptions, the undeniable divergences in our disciplinary approaches cause us to constantly challenge each other's notions, and even sometimes reassert our previous perspectives. Rather than serving as obstacles or impediments to working together, these tensions, compromises, and negotiations are ultimately what give rise to new, productive collaborative possibilities. We explore the impact of this process on the ‘return' to our respective fields, as they continue to shape the outlook and outcomes of our separate anthropological and artistic practice.

Individual Projects and Interests

<3> SELENA: My work begins with research, and develops out of images and texts recovered from archives, or through fieldwork generated with the help of collaborators. While exploring other people's stories (for example, those of Victorian spiritualist mediums, or my neighbors in Brooklyn), I look for specific details that trigger a spark of recognition in me, such as the expression on someone's face

at the margin of a photograph.

Such details provide a vehicle for me to address broader themes of social history and cultural memory.

<4> My working process has been greatly influenced by the art/science collaborations of the Mass Observation movement of the 1940s. Launched to subvert the sanctioned images of English society, these researchers collected and published anecdotes, snippets of conversations, and the daily habits of ordinary people. It is this focus on collecting and honoring the mundane fragments of life in order to elicit a larger cultural portrait that I find inspiring. The social history paintings of Luc Tuymans and Gerhardt Richter, and the conceptual paintings of Marlene Dumas have also made a strong impact on me. I am primarily a painter, who has come to use the diverse media of sculpture, collage, photography, and film as alternate means to expressing what I see through the act of painting.

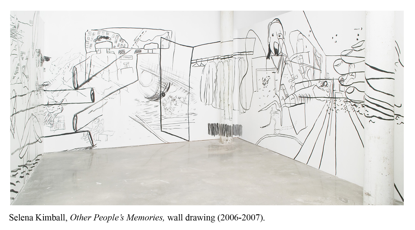

<5> My work probes the boundaries of collective and individual experience, particularly in relation to history and memory. In one of my last projects, Other People's Memories (2006-7), I collaborated with friends and neighbors in New York, using interview techniques to elicit descriptions of mental pictures of their memories. I then asked them to draw these images, which I collaged together into a collective installation. Another project, consisting of my own oil paintings, A History of Things I Remember but Will Never See (2007) contains portraits of Americans watching major events in recent history. I found the original images in the peripheries of news photographs, and recast them as central figures in the new contexts of my paintings. I wanted the gaze of the figure in the portrait to become the focal point of the viewer's gaze, with both sides looking back at one another, first-person narratives intersecting with broader collective associations.

<6> ALYSSA: My current doctoral research at the University of Manchester is about remembrance work in the urban context of Bucharest, looking at its politics and poetics in order to more deeply understand Romania's current period of post-socialist transition. I have experimented with forms of investigation conducive to studying the uncertainties, elusiveness, and contradictions of memory, to access these invisible, imagined storehouses lodged in individuals' minds, and the social contexts of their creation. My research has led me to regard remembering not as a purely conceptual or intellectual act, reduced to cognitive or linguistic models, but rather as a corporeal activity involving palpable, embodied feelings (cf. Benjamin 1999; Connerton 1989). In order to grasp memory's "imageric and sensate" qualities (Taussig 1992: 8), I have adopted approaches operating within a sensory register analogous to the process of remembering itself. These have included a focus on everyday social behavior, dreams, and the imagination, and the use of experimental filming techniques in my fieldwork. As a visual anthropologist, film has been an integral component of my research, and I plan to supplement the written text of my doctoral thesis with a visual ethnography.[3]

Collaborative Background

<7> Our collaborative work bridging art and anthropology has been developing over the past fifteen years. In the mid-1990s we both were undergraduates in Providence, Rhode Island (Selena studying sculpture and painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, and Alyssa studying anthropology at Brown University), and would regularly sit in on each other's classes, exchange bibliographies, and discuss ideas for our respective papers and projects. Our constant communication and involvement in each other's disciplines evolved over time; we absorbed each other's ideas and discourses without realizing how deeply they affected our modes of perception. These experiences led to informal collaborations, initially more about process than product; the final result never seemed as important as having the chance to look at things in a different way when sharing in each other's development of ideas. At that point we lacked the experience and theoretical language we needed to articulate the specific points of intersection of our interests, but we must have possessed a bit of what Hal Foster ironically refers to as ethnographers' "artist envy" and artists' "ethnographer envy" (Foster 1995: 304). These qualities need not be seen as negative, however, as they indicate a curiosity and a drive to seek something un-nameable that seems to be lacking in one's own experience.

<8> Over the following years, we developed more of a shared vocabulary, and continued working together on a variety of more "finished" pieces: oral history projects, short films, and site-specific installations. In 1997 we spent a month traveling around Romania, experiencing its post-socialist atmosphere first-hand, testing the waters for developing a collaborative project there; this experience eventually led Alyssa to her post-graduate research focus on the region. She returned to Bucharest in 1999 with a year-long Fulbright grant to do research at the Museum of the Romanian Peasant, ultimately co-curating an exhibition there with Selena. The exhibit reflected our correspondence during that year, and incorporated artifacts Alyssa had collected during that period, Selena's paintings referencing these objects in the context of Alyssa's fieldwork, and fragments of Alyssa's writing responding back to these paintings. Our work in Romania continued in 2005, when Alyssa made a film about the everyday lives of nuns in a Romanian Orthodox monastery for her MA degree at the University of Manchester. Selena spent a month in the field helping Alyssa with sound recording, adding her own voice to the ethnographic narrative by contributing humorous 16mm stop-motion animation sequences commenting reflexively on the experiences of filming and fieldwork. In these projects, our actual "creative processes" remained largely separate, with Alyssa generating most of her material in the field, and Selena producing much of her work in the studio. Underlying these divisions, however, was a consistent shared desire to access the seemingly invisible perceptions of others, and translate these into new forms.[4]

<9> During Alyssa's year of doctoral fieldwork in Bucharest in 2007, we decided to take our collaboration to a new level. We wanted to engage in a joint project generated within the shared space of the field, and produce something that could resonate with audiences in the domains of both art and anthropology. We did not want to frame this work according to more commonly accepted ideas of collaborative practice, with "an artist contributing to ethnographic fieldwork," or with "an anthropologist serving as consultant for an art venture," but rather to come to new understandings through jointly seeing and responding to the material at hand. By taking on our disciplinary differences, by examining and confronting them, we would view them as a source of inspiration and a point of departure for our emerging collaborative work. Such an approach departed from other examples of interdisciplinary work we had encountered in the past. Our individual contributions would be strongly rooted in our respective backgrounds, but the process and product, we hoped, would be less clearly divisible along disciplinary lines.

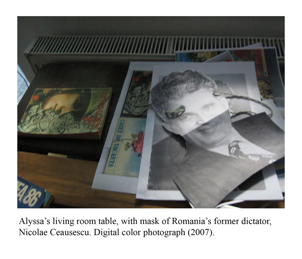

Disciplinary Histories

<10> The fields of anthropology and art have referenced each other since each discipline's beginnings. [5] They share many elements in subject matter and approach, serving as important sites of cultural production, and for critiquing cultural activity and conditions of modernity (Marcus and Meyers 1995: 11, 35). They both involve practitioners who attempt to understand "common sense, everyday practices… and a willingness to be decentred in acts of translation" (Coles 2000b: 56). Both fields have contributed to the long-term debates surrounding the fine line between "art objects" and "ethnographic artifacts." Western art traditions played a significant role in shaping anthropologists' analyses of cultural production, while anthropology's figure of the "primitive" is deeply embedded in the discourses of avant-garde and modern art (Marcus and Meyers 1995: 14).

<11> Artists have long adopted the subject matter and methodologies of the social sciences, but usually deliberately modify them to meet their own ends. As James Clifford (1981) points out, the French Surrealists were some of the first contemporary artists to engage in discourses about "reality" and the "other" in their efforts to comprehend and interpret the human condition. Yet while ethnographers wish to render the foreign familiar (through "defamiliarizing" the known world), the Surrealists aimed to make the familiar appear strange, even unknowable. Instead of seeking an authoritative knowledge over the "other," they instigated a "disruptive and creative play of human categories and differences, an activity which…openly expects, allows, and indeed desires its own disorientation" (Clifford 1981: 558). Yet the French Surrealists' intense questioning of accepted norms, challenges of positivist rationalism, and desire to access hidden truths through dreams and the unconscious do not always sit well with the more conventional anthropological goals of intellectual clarity and logical explanation.

<12> More recently, the Relational Aesthetics movement, coined by Nicolas Bourriaud in 1996, took to exploring the functions of society and human intersubjectivity, specifically addressing the "realm of human interactions and its social context" through works of art (Bourriaud 2002: 112). While its practitioners, artists such as Rikrit Tiravanija, Pierre Huyghe, and Maurizio Cattelan, tend to engage with issues of human and social relations similar to those addressed in fieldwork, they do not usually engage explicitly with the discipline of anthropology, or overtly reference its literature or theories. They depart from an anthropological approach by instigating certain social situations that actively implicate the viewer, as opposed to prioritizing the acts of ethnographic observation and interpretation.

<13> The recent "ethnographic turn" in art has signaled that it is now acceptable and not uncommon for visual artists to incorporate ethnographic methods into their work (cf. Coles 2000a). Certain artists, such as Sharon Lockhart, Gillian Wearing and the collaborative team Andrea Robbins and Max Becher, employ "fieldwork" types of practice by actively using the public sphere as a site for their art.[6] Others such as Christian Boltanski, Fred Wilson, and Marc Dion have explored a wide range of anthropological activities, such as collecting, documenting, archiving, and exhibiting objects, commenting upon and reinterpreting such practices in a variety of ways. [7] The artists Nikolaus Lang and Anne and Patrick Poirier have questioned and critiqued certain ethnographic methods of classification and representation, through deep engagements with their interlocutors and the cross-cultural contexts of their work (cf. Schneider 1993). However, not all artistic approaches claiming to adopt processes of participant observation and data collection are fully representative of the academic conventions of ethnography. As critics have warned, contemporary artists' usage of a "pseudo-ethnographic" paradigm may ultimately reinforce anthropological authority, and play into dangerous stereotypes of anthropology as a "science of alterity," reinforcing notions of primitivism by "re-fashioning the other in artistic guise" (Foster 1995: 307).

<14> Over the past few decades, anthropologists began to broaden their studies of art, by analyzing its position within the dynamics of power and political struggles, and exploring the social and cultural dimensions of aesthetics (MacClancy 1997). They have written ethnographies about discourses within the "art world" (Marcus and Meyers 1995), or about the production and consumption of art and artifacts as social processes (Svašek 2007). Yet much of this work continues to treat art as merely another ethnographic object of study, rarely departing from the traditionally realist discourses of the social sciences (Schneider and Wright 2006: 18). Despite the discipline's attempts to experiment with textual and literary forms of ethnography, largely a part of the "writing culture" movement in the 1980s, such work is still largely marginalized within academia (Schneider 2008: 171). Many conventional anthropologists continue to question the legitimacy of the discipline's uses of media such as photography and film, and visual anthropology is largely treated as a "sub-discipline" (Schneider and Wright 2006: 23), with the camera seen as a research tool (T. Asch and P. Asch 1988), and images serving as mere illustrations or pictorial modes of conveying ethnographic information (Ruby 2000).

<15> It is only in the last few years that innovative dialogues between the two disciplines have provoked academics to approach this subject in a fundamentally different way. What are referred to as the "sensory" and "corporeal" turns in anthropology have been recent disciplinary concerns (for example, in the work of David Howes, Steven Feld, David MacDougall, and Paul Stoller). Visual anthropologists in particular are increasingly recognizing the importance of the role of subjective, sensory realms in the process of cultural interpretation (cf. Pink et. al. 2004), and focusing on how the integration of non-verbal modes of communication into anthropology can essentially shift an investigation from a cognitive, descriptive exercise to an emotional, experiential one, closer to those involved in the practices of contemporary art (Grimshaw and Ravetz 2005). Film is most often explored as a medium conducive to such a process, as its mimetic qualities provide a "tactile and habitual" consciousness of the world (Taussig 1992: 11). The embodied, material experience of vision involves the researcher in a corporeal engagement with the subject, and can lead to new kinds of analytical knowledge, constructed through "acquaintance" rather than mere description (MacDougall 2006: 220). Contemporary ethnographic filmmakers concerned with this process advocate bringing together the "anthropologies of the visual" with the sensual knowledge stemming from visual practices, in order to enlarge and enrich their repertoire of strategies of knowing (Grimshaw and Ravetz 2005).

<16> While such ideas tend to be written about more often by anthropologists than artists, projects actually carrying them out are still more likely to occur (and be accepted) within an art context than in a social science arena. Academic articles and dissertations usually are expected to be text-based, while artistic projects may incorporate a wide range of both written and visual media. The collaboration we discuss in this article attempts both to relate to the existing theoretical literature about such practices, and to concretely contribute to the developing body of such works.

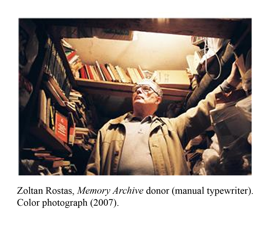

Productive Tensions

<17> As Julia Kelly claims, ethnography may be more "amenable to the ‘creative' impulses of the artist" than other sciences (Kelly 2007: 5); yet its practitioners are not always likely to unreservedly adopt the terms of artistic practice. Artists are free to rely on their own subjectivity for inspiration, while anthropologists are bound to a subject of study necessarily outside the self. While artists tend to embrace a sense of ambiguity or uncertainty in their practice, anthropologists have traditionally been directed to the act of comprehending and explaining (Kelly 2007: 2; Ravetz 2007b: 275). There are fundamental tensions between ethnographers' attempts to qualify images related to their fieldwork, and artists' tendencies to "escape closure" in their use of images (Ravetz 2007a: 248). Artists often set out to disrupt the spaces around them, to set up tripwires and provocations for the viewer. In contrast, anthropologists learn that scientific work should involve representations that "reflect reality as transparently and faithfully as possible" (Henare et. al. 2007: 11), and that prioritize their informants' experiences over their own. They are taught to try and minimize their own interferences in the field, to recognize their subjective presence, if not as a direct liability in their research, at least as an issue to acknowledge and responsibly communicate to their audience. Artists are not expected to qualify or quantify their practices, nor are they required to abide by the certainties of linear thinking or logical analysis (though they are certainly free to do so). Their underlying aims, like those of anthropologists, may be to grapple with understanding aspects of human society, but they do not necessarily interact with human subjects in this process, and consequently are not bound by the same kinds of ethical or disciplinary obligations as anthropologists are toward their informants.

<18> Such differences, however, can inspire and provoke a self-reflective attitude in both parties, setting the stage for interdisciplinary work. Functioning within one's own context, one's identity is self-evident; most premises of operation are taken for granted, and need not be explained to one's peers. However, working across disciplines requires one to justify or explain to someone else the sets of assumptions and activities within one's own field. Suddenly the previously unquestioned elements of one's own identity become significant. They must be articulated and clarified to the other person: what is unique about one's particular approach, and what distinguishes this work from similar practices? Such explanations can sometimes be dangerous, leading to simplistic or essentializing concepts about what each practice is or what its practitioners do; but they can also be useful, provoking both sides to clarify their goals and working processes, while recognizing that their identities are not fixed or static, but rather open to new approaches and ideas.

Object Dialogues

<19> SELENA: Everybody was always asking us, "Why Romania?" Ten years ago, Romania was an undefined place for me. And yet it had taken hold of my imagination. My impressions of the country were based on two (visual) traces: a shoe and a picture in the newspaper. I had previously found a pair of ochre leather shoes in a resale shop, stamped in a strange font with the words "Made in Romania." A few months later, I read in the New York Times about the country's then-elected President, Emil Constantinescu, a former geography professor. Any country choosing an intellectual as its new political leader, and dyeing its exported shoes with the most audacious of yellows, struck me as an unusual and intriguing place. I wanted to go there before these particular colors and political configurations started to fade or change. I was aware that I was projecting my own desires onto this unknown land. But I felt I must follow these instincts. Planning the trip there with Alyssa, we thought that it could ultimately form the basis for some future work together. We just had no idea what the shape and extent of this work would be.

<20> ALYSSA: My interest in Romanians' memories is inextricable from my own memories of the country, even if these are drawn only from its last decade of post-communism. I had seen many changes over these years, but I would always remember when Selena and I first traveled there in 1997, how the feeling of communism still coated the surfaces of streets, buildings, people's physical bearings and expressions, in a very palpable way.[8] I could see that this patina was slowly wearing away, but I held these images in my mind during my year of fieldwork in 2006-7, and drew upon them whenever I would encounter evocations of Romania's recent past. [9]

<21> Through my fieldwork, I wanted to learn more about how people's relationships to their own memories were changing, and what new practices were emerging as Romania's global position continues to shift. But memories are often so well camouflaged in the fabric of day-to-day life that they can be extremely difficult to identify. While in the field, I watched, listened for, and sometimes even provoked remembrance discourses and practices throughout Bucharest. I was concerned with how memories were expressed, suppressed, or absent among different generations and social classes; how they were deliberately and inadvertently politicized or commodified; what forms they took; where they could be found. It was important for me to investigate not only "official" realms, such as museums, public monuments, and state politics, but also "unofficial," everyday contexts, within the ordinary public and private spaces around the city.

<22> I began collecting artifacts from people, as a means of accessing memories that were difficult to see or uncover through mere discourse. I asked people to give me an object they had lying around their house, something they associated with the period before 1989. I did not want anything with high monetary value, but rather something simple, that they wouldn't mind giving away for good. I discouraged people from donating objects with obvious political connotations, or stereotypical things such as old bread coupons, Communist Party manuals, or other propagandistic texts. I was just looking for ordinary objects, tucked into the most banal corners of people's lives, which somehow had a connection in my informants' minds to the period before the Revolution.

<23> Many people were initially perplexed with my request; they hadn't consciously thought about the existence of such objects for years, or if they had, they didn't understand why such "junk" would be interesting to me. Some people even told me that they couldn't possibly have anything still in their possession from that era. Sometimes I would have to literally walk with them around their flats to start to find these artifacts. Taking a mental inventory of what was in their cupboards, closets, and cabinets brought to the surface memories they hadn't thought about in years. Literally rummaging around these storage spaces made their memories tangible in some way, and invariably evoked further stories, musings, and recollections. When the person would find or decide upon an appropriate item to donate, I would ask them to write a few sentences about it, to describe what it was and what place it had in their memory. Ultimately I would film them reading these written statements, which often led to more extended discussions about the past, which I also filmed. Gradually I put together my own miniature, material archive of these objects. I hoped that eventually they could serve as a new context within which to understand the memories associated with and generated by their collectively constituted world. [10]

<24> When Selena came to Bucharest, intending to stay 2 ½ weeks in the field with me, she brought her 16mm Bolex camera, eight minutes of film, and the idea that somehow she would use this collection of objects in a series of stop-action animations.

<24> When Selena came to Bucharest, intending to stay 2 ½ weeks in the field with me, she brought her 16mm Bolex camera, eight minutes of film, and the idea that somehow she would use this collection of objects in a series of stop-action animations.

<25> SELENA: "I have been collecting objects that are connected to people's memories of the past," Alyssa had written to me. "They are hidden in drawers, under people's beds. Maybe we can do something with them."

<26> I flew from New York to Bucharest in August 2007. It was hot. I was woozy with jetlag. My tripod arrived at the airport three days after I did. In this unsettling state of mental and physical transition, Alyssa introduced me to what I have come to think of as the archive. I had encountered other artists working with this concept, playing with the idea of collecting and documenting historical materials. Much of my own practice begins with research--collecting cultural data from photographic archives or generating my own field research--as the raw material out of which the finished work develops.

<27> This particular "memory archive" was a collection of a dozen or so objects from Romania's pre-Revolution era, collected by Alyssa over the previous months, and temporarily stored on basement shelves at the Museum of the Romanian Peasant. She brought me to see them the day after I arrived in Bucharest. There they were: frayed at the edges, rumpled, ordinary, but compelling, with the beauty and dignity of aged ballerinas no longer on stage but embodying a deep physical knowledge of their pasts. That is what I trusted them to be: bearers of a certain kind of knowledge. These objects were characters with stories and pasts and legends and desires of their own.

<28> Alyssa had told me of her acquisition of these objects during our phone conversations over the course of her fieldwork. She had brought her video camera into people's homes and interviewed them about these ordinary artifacts to elicit their memories of the past. As I remember Alyssa's accounts, often people would not initially recall having kept any objects connected to "pre-1989" times. And then, slowly, in the course of the conversation, they would start digging around their drawers and cupboards, pulling things out: an ice cube tray, a school uniform, a manual typewriter. Histories of the object and memories of their pasts bubbled to the surface at their ‘discovery.'

<29> From her conversations with me, what Alyssa seemed to find most compelling were the narratives accompanying these objects; these accounts deepened her understandings of another time and place that she could not herself physically access, another experience of reality. The ordinary qualities of these retrieved communist objects connected her to this otherwise unknowable time. I began to see these objects as embodied memories, a means for Alyssa to relate to and empathize with a past that was not her own.

<30> ALYSSA: My collection consisted of the following items: An aluminum ice cube tray. A blue polyester schoolgirl's uniform. Two unmatched socks (one with a patch) and a handmade garter. A miniature porcelain statuette or bibelot. A metal seltzer water bottle. A wooden mushroom for darning socks. A collection of five little recipe books. A heavy manual typewriter. An old glass ink bottle, filled with blue ink, paired with a plastic pencil case. Two almanacs from 1986 and 1987. A mesh sack for carrying food purchases. A large glass pickling jar. A package of Vegeta food seasoning. A pair of eyeglass frames without the lenses. A hand-painted rayon scarf. A photograph of a schoolgirl sitting at her desk. A set of 36 educational slides (called diafilme in Romanian) about the "History of the Fatherland." A pair of circular knitting needles, still in their original packaging, imported from Germany.

<31> Selena told me that her interest in these objects was not necessarily culturally specific, but rather related to their more universal qualities. I had recounted to her where the objects came from, fragments of their personal histories. But she wasn't so keen on reading people's texts about them, or watching my taped interviews. She was less concerned with their individual personal or social narratives than their existence as generally recognizable objects. But how could she expect to treat these items as some kind of archive, I wondered, without even considering the facts of their documentation?

<32> I also valued their "objecthood"; the physicality and materiality of these mundane things from another era were visually intriguing, even oddly beautiful. But these items were significant foremost because of their individual and cultural associations. For me, it was essential to know who had donated them, what they had meant to their original owners, and what were the stories surrounding their existence. I had documented these facts as any good ethnographer should. I had my inventory of written statements about each object, and video recordings of each person reading these texts, and talking about their memories.

<33> SELENA: Oh, the expectation that objects will tell us their secrets, tell us the stories of what they have witnessed. Alyssa viewed the objects as literal traces of their histories that emerged through her interviews about them. Could I, too, get to know these stories, but in a different way, not by intellectually processing them, but by looking at the objects, handling them, interacting with them? As James Clifford notes in an interview with Alex Coles, "We operate on many levels, waking and dreaming, as we make our way through a topic; but then we foreshorten the whole process in the service of a consistent, conclusive voice or genre. I wanted to resist that a bit" (Coles 2000b: 71). I decided not to watch Alyssa's interviews or read her texts.

<34> ALYSSA: Working with Selena would require me to relinquish my anthropologist's urge to preserve the original contexts of these objects I had collected. When Selena encountered the jumble of items in my collection, she photographed each object for her own records, and subsequently warned me that she might eventually have to "destroy" them. With one exception, I had collected items that did not need to be returned to their donors, and theoretically I could do what I wanted with them. Destroying them was one possibility I had never considered, but now had to accept, if I were to participate fully in our terms of equal collaboration. This element of creative tension between art and anthropology challenged my training to avoid transforming an informant's story, or transfiguring a collected artifact's material reality. I was no longer the documenter of their histories, the conveyer of their messages; instead I would have to treat them more as an artist might, and even physically relinquish them to somebody else's hands.

<35> SELENA: Alyssa had told me about Ceauşescu's motto during communist times, "Recuperate, Recondition, Reuse,"[11] and it got me wondering how this phrase could apply to our own archive of outmoded objects. In the 1980s, when this particular slogan was in circulation, these objects were also socially circulating. People were regularly making their seasonal pickles in pickle jars, wearing and darning their socks, adorning their living room shelves with miniature porcelain figurines. It's not that such activities no longer occur today, but the actual items in our collection were no longer being used for such purposes. Certain technologies connected to these objects have been replaced by more "efficient" and "modern" ones. (Many people now buy preserves instead of making them themselves; socks with holes are often thrown away rather than mended; porcelain kitsch has been replaced with newer fashions of plastic kitsch.) They had become remnants of the past, containing fragments of memories from a time no longer immediately visible.[12]

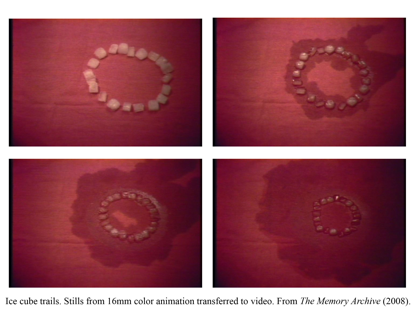

<36> How could I approach the task of recuperating, reconditioning, reusing them, if they were no longer attended to by their previous owners? Could I somehow "re-animate" them myself? Ceauşescu's directive reminded me of American animated instructional films I'd seen from the 1950s and ‘60s. These films had titles like "Stay Safe, Stay Strong: The Facts about Nuclear Weapons," and "How to Use the Dial Tone." The animated "how-to" film showed, step by step, the practical ways in which objects should be approached and handled. I thought about using this form, the "how-to" film, as a jumping-off place for filming these collected communist objects.

<37> The collision between the "how-to" film, which was all about practical instruction, and these objects which had no practical use anymore, was interesting to me. Could we, in our own "instructional films," show something about how memory works? How it doesn't work? Could we use the trope of the "how-to" film to bring out precisely the un-how-to, the impractical qualities, the latencies, and the fragmentary tactile feelings of the objects in our archive?

<38> ALYSSA: Selena spent a few days simply thinking about how to proceed. I was not really included in this stage; to me it was an invisible, intangible, and very individual process of gestation. I watched and waited as she took notes, and began to generate ideas. She would occasionally accompany me in my daily errands and tasks around Bucharest. But it was evident that her thoughts were directed inwards at this point, and not towards her external surroundings. This was counter to my own experience of self-integration in the field, where I tend to put my energies outwards, into the social activities and the routines and rhythms of the people around me.

<39> SELENA: Being in a foreign place shatters my habits of perception, and offers me new ways of seeing my everyday surroundings. Objects that are familiar to me at home suddenly are different, made strange. An ordinary Romanian jar suddenly would stand out to me, not for its function or contents, but for its unusual shape, or the color of its label. The way Alyssa's telephone rang in Bucharest was a new sound to me; when someone would call, I was no longer aware of its existence as a tool for communication, but as an object that made a lovely, unusual noise. This new type of engagement with the material world around me that stems from being in the field has shaped my artistic practices; it is an ongoing reminder to not take the forms and artifacts around me for granted. [13]

<40> ALYSSA: When we started trying out Selena's ideas, she would choose the objects and direct the animations. But we would both be involved in the filming process, taking turns being the cameraperson and the object manipulator. Sometimes we would discuss the plan beforehand in detail; other times we would improvise. With 16mm animation, you take single frame exposures, and move the objects within the frame only a slight amount between exposures. It is a slow and laborious process, and something that becomes a 30-second animation takes hours to actually film. We had to deal with problems like the light changing during the course of filming, or the camera not fitting into the right spot, or having to rig up the objects so they could be more easily manipulated. The whole process required an odd combination of having to be extremely serious and patient and exact, and at the same time acknowledging how ridiculous and silly the entire endeavor seemed. We also had no idea how the animations would look until Selena returned to the U.S. to develop and process the film. Rather than being able to rely on fixed, reliable footage, we had to guess how these sequences would eventually appear, and consequently we were always referencing and involving our own memories and imaginations in the working process.

<41> SELENA: The field itself is a mental representation. When I was in Bucharest, encountering the sights, sounds, and tactile qualities of the city--its objects, its parks, its architecture, chance encounters with strangers--I was collecting a network of perceptions and understandings through my senses. The "field" became the very mental residue of my experience of it; first mediated by my attention, taken in by the subjectivity of my sense organs, and later forming itself as this place in my mind. My engagement with, and reworking of this mental representation, is what I have come to think of as "fieldwork."

<42> ALYSSA: I began to realize that Selena was transforming my flat into a studio space. This became very clear when my chairs got stacked up in a corner, sheets of newsprint were scattered across the floor, the dining room table top was dismantled and used as a drawing surface, and my balcony became the stage for filming the animations. My apartment, the quiet and orderly place that I would normally come back to in order to rest and reflect on my experiences after a busy day running around town, became a chaotic worksite. It was not geared toward such a function; we had to improvise everything, propping the tripod on boxes stacked on my balcony, tying scraps of paper together and taping them on the clothesline to control the light. Participating in this activity changed my relationship to my fieldwork space as I had configured it as an ethnographer, requiring me to enter into a different mode of seeing, perceiving, and living in my surroundings.

<43> SELENA: I am interested in fieldwork as these accumulated, lived moments of sense perception (one could define it as a kind of artistic data-collection). It is a sensory knowledge of a place developed over time; just as anthropological knowledge is formed by observing places and people over a distinct period of time. In conducting fieldwork, ethnographers must use their eyes, their ears, their hands and feet. The difference between these practices and those of an artist may lie in what is valued in this experience. Anthropologists do not traditionally take the "raw data" of their own sensory perceptions as their subject matter, but rather certain "facts" drawn from their material. I am interested in the very substance of my sensory, empirical perceptions formed through my encounters in the field.

<44> ALYSSA: We filmed most of the animations on my balcony; but we decided to film a few of them in various locations around Bucharest. Once we would choose a site, we would usually stay there filming for hours, dripping in the intense August heat, dealing with the stares of the passers-by, and even occasionally being photographed ourselves by curious onlookers. Though this experience was often uncomfortable, I found my relationship to the city changing because of it. I began to see parts of Bucharest, already the subject of my field investigations,[14] as extensions of the studio recently created in my apartment. Staying in one spot for several hours cultivated a familiarity, and surprisingly, a kind of intimacy, with the contours of the space, and a knowledge of a public sphere that cannot be achieved by merely passing through it on your way to somewhere else.

<45> I felt a growing intimacy with the objects as well, as animating them meant spending much more time with them than I otherwise would have. I developed a kind of attachment, even affection, towards them, getting a sense for how their original owners might have related to them, how it might actually feel to have them as part of my material landscape over a period of time. I spent hours holding their weight in my hands, inspecting them from all angles, crouching down next to them and moving them around for the camera, one millimeter at a time.[15]

<46> In order to animate some of the objects, we also had to put them to use, which gave me a physical, bodily acquaintance with them. In order to make an animation with the old aluminum ice cube tray, for example, we had to first freeze water in it, and experience the cumbersome way of trying to extract the cubes from their inflexible plastic frames. To animate the wooden darning-mushroom and one of the socks, we first cut a hole in the sock (which needless to say I was reluctant to do), and then sewed it up with the aid of the wooden mushroom. It was the first time I had used such a device, and was able to discover how it felt to hold it; it surprised me how functional it actually was. Lugging the heavy manual typewriter all around Bucharest's streets to try and find a suitable place to film it allowed me to learn what it must have felt like (at least physically) when people were legally required by Ceauşescu to bring in their typewriters every year to register with the police. Such direct types of contact with these objects gave me another layer of empathic, sensory understanding about a past that I did not (and cannot) directly experience myself.

<47> The act of handling the objects during filming, and allowing them to be manipulated by someone else, was directly counter to the anthropological trend of collecting as a means of preserving or "salvaging" the memories of my informants. Instead of putting these objects behind a glass case or into a temperature-controlled storage unit, I was exposing them to the elements, allowing them to be touched, potentially damaged, even dragged around the city. I would no longer be their "translator" or spokesperson, but rather an active collaborator in reactivating and reincarnating them in a new context.[16]

Post-Fieldwork Narratives

If you think about the narrative that collections or assemblages of things make, the interesting thing is that there are always at least two possible stories: one is the story that the narrator, in this case the artist, thinks she's telling--the story-teller's story--and the other is the story that the listener is understanding, or hearing, or imagining on the basis of the same objects. And there would always be at least two versions of whatever story was being told.

–Susan Hiller, "Working Through Objects" (1994).[17]

Ice Cube Tray

I. The story of F.G., (f), born 1953; human resources assistant, Bucharest:

<48> It's from the FRAM[18] ---the polar bear, that is, our old refrigerator, which consumed a lot of energy, in which we made cantaloupe ice cream for the first time, which... spilled over into the whole fridge because it no longer froze things at all!<49> When we bought another fridge, an ARCTIC from Găeşti (1978), our poor FRAM became... coop for the chickens in the countryside.

The animation:

<50> Shot of hands tipping the tray downwards to empty it. Close-up of ice cubes (strung up by threads) falling downward in slow motion. Bird's eye view of cubes landing one by one onto a pink surface, where they move clockwise in a gradually shrinking circle as they melt and then disappear. Repeat of initial shot of hands with tray and ice cubes falling. Bird's eye view of cubes landing and moving in rows, marching towards the top of the frame as they melt. The ice cubes leave wet traces of their paths on the cloth. The stains remain after the ice disappears.

II. The storytellers' story:

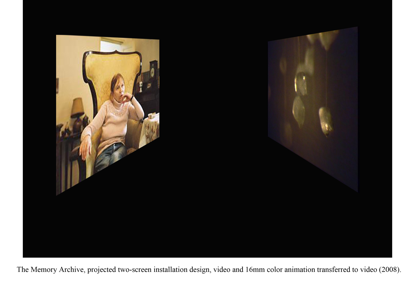

<51> Visibility of time. These animations capture motion in space, but in showing the ice actually melting and disappearing, they quite literally index the passage of time. Traces created by the water remain after the actual object is gone, evoking the phenomenon of an "after-image" once you close your eyes, or the persistence of visual memories lodged in the mind.

Almanacs

I. The story (excerpt) of C.T., (m), born 1970; museum treasurer, Bucharest:

<52> The appearance of these newspaper supplements and publications was feverishly waited for--in their own way, in apartments that lacked Heating Agent 007's services[19] --around the end of each year. When they appeared in the shops, people would whisper on the street corners, and sidle up to the printers. It was made known to the storekeepers that they wouldn't be let down if they set aside a copy for those who ordered it.[20] With an almanac you could very well get yourself to the dentist, obtain two tins of pineapple, prove your love for your wife... [21]<53> Usually the almanac would be read back to front. At the end were the entertainment columns: games of logic, tests of self-knowledge, stupid jokes and caricatures. The closer you got to the middle of the book, the more challenged you were: researchers from the University of Bremen discovered I-don't-know-what types of new weeds compared to last year--you were never able to prove this sort of thing--Western Europe was illustrated in black and white, only showing drug addicts and homeless people; the Americans were uncultivated because 80% of them didn't know who their president was...…

The animation:

<54> Medium shot showing the two almanacs; the cover of one (1987) with a close-up profile of a Romanian soldier, and the other (1986) with a pink geranium on it. The sequence consists of the soldier-book trying to get close enough to the geranium-book to smell the flower. It heads toward the flower, bumps up against the book, travels around it and then slides itself over the other's cover to lean over and press its nose against the geranium.

II. The story-tellers' story:

<55> Allusions to the sense of smell as a powerful means of evoking the past. The soldier became more human through the exercise of trying to animate him. He started to develop a personality and somehow became more endearing to us as a character. We both started rooting for him to succeed in smelling the flower, and empathizing with his difficulties (it was hard to move the cover of the book without our hands appearing in the shot).

Seltzer Water Bottle

I. Story of M.P., (f), born 1969; ceramicist, Bucharest:

<56> In the old days, the seltzer bottle was the ordinary person's mineral water. It was hardly ever absent from the table. Men were the ones who used it most often to make spritzers.[22]<57> When I was a child I was often sent to the seltzer water shop to trade in the cartridges, which I was never too happy about. On the other hand, I liked drinking carbonated water from the seltzer bottle, even though I preferred natural mineral water from the spring. I especially remember certain Sunday meals in my grandmother's courtyard, where the seltzer bottle cooled you off in the scorching heat.

<58> There were many different types of seltzer bottles: the old ones were glass with a wire mesh covering. The more "modern" style was made of colored metal (aluminum?)... For me, this object is one of the very ordinary objects I grew up with, but now it provokes in me a funny nostalgia...

The animation:

<59> We placed the bottle in the middle of the parking lot in front of the Palace of the People,[23] and moved the camera (instead of moving the object) in a 360 degree circle around it. The initial wide frame changes to a close-up so that the reflections of the surrounding buildings and streets are shown moving around the curved metal surface of the bottle.

II. The story-tellers' story:

<60> Selena spent two hours in the infernal sun doing this tedious job while Alyssa stood around and tried to keep the waves of tourists from stepping on the bottle. Staying in one spot for such an extended period of time, we got a sense for who frequents such a space. Several loads of tour busses came. People would get out, snap a few photos of the Palace, wander around the parking area in a daze, and then leave. A few times tour guides would notice the bottle and we heard them explain to the tourists that these were what they used to use during the "difficult times of the 1980s in Romania." Only one American tourist directly asked us what we were doing. One woman almost stepped on the bottle because she wasn't looking where she was walking and got annoyed when Alyssa waved her away. A few people asked Alyssa to take their picture with their own cameras, of them posing in front of the Palace. Several times we saw people posing for each other with their arms outstretched so the picture would portray them as if they were holding up the Palace on their shoulders. Playing with scale in a place like that seemed to be a common response.

Sock and Wooden Darning Mushroom

I. Story of S.C., (f), born 1976; assistant university lecturer, Iaşi:

<61> The white socks always got in the way of my playing. They were part of the school uniform, and they were supposed to always be impeccable.<62> In the mornings, my grandmother had a ritual, which I sometimes would see, with eyes half-open, if I were to wake up for a few minutes at dawn. I would watch her on the edge of the bed, putting on three layers of socks, one by one, in the frosty days of winter. First the tattered socks, and then the "good" socks, fastened with the "garters" she'd made herself.

Story of I.B., (f), born 1938; university professor (French Literature), Bucharest:

<63> This mushroom spent a few dozen years in my mother's sewing basket, beneath the heap of socks to be darned; she had turned it[24]and painted it herself, back when she was making wooden painted toys and mărtişoare [25] and selling them wherever she could. The heap of socks and stockings waiting to be darned would get smaller, but I never saw it completely disappear. Or if it did, it was just until the next day, when I was at home. The colors painted on its cap have been rubbed off, probably onto my mother's fingers.

The animation:

<64> The sock is strung up horizontally across the frame. The mushroom travels across the length of the sock until it reaches a hole. It turns around in the hole to encounter fingers holding needle and thread. The hand mends the hole with the mushroom's aid, and the mushroom then travels down the sock, back to wherever it came from.

II. The story-tellers' story:

<65> We put two objects, given by separate people, together in a single animation. This created a dialogue between individuals who did not know one another, from two different contexts, pointing to issues of collective memory. It is also an important reference to inter-generational female relationships and continuity through time: the sock had belonged to its donor's grandmother, and the mushroom had belonged to its donor's mother. This was another animation that required us to interact with the objects and physically put them to use, which allowed us a more direct sensory understanding of other peoples' pasts.

<66> ALYSSA: When Selena returned to America and processed the film, she mailed a rough cut of the animations back to me in Romania. It was then that I began to wonder about how to present such images, and the form the finished product would take. What I was trying to convey anthropologically through these fleeting vignettes? How did they fit into the rest of my Ph.D. research, and into the other filming that I had been doing throughout my fieldwork? Should we present the animations on their own, or frame them with some sort of ethnographic explanation?

<67> SELENA: For me, the "truth" of these animations lay precisely in their open-endedness. I did not want to reproduce other peoples' memories, or translate their subjective experience; I didn't feel the need to "explain away" their meanings. It was not my intention to illustrate particular memories, but rather to evoke memory's fluidity and its subjectivity: how it operates, how it feels.

<68> My goal was to set up a dialogue between the subjectivities of the artist and anthropologist, the objects in the memory archive, and the personal responses of the audience. I saw three sets of stories in the material we had generated thus far: the specific recollections of the Romanian participants, the stories of the subjective responses of Alyssa and myself, and the stories the viewer would come to understand in light of all of these factors. I wanted to remain true to all three sources, and create a space for multiple stories, and multiple storytellings, in the context of our single project. We initially tried to visualize this project as one continuous film, knitting together the ethnographic interviews Alyssa had shot with the stop-motion animations. But the contrasts between the aesthetics and composition of each seemed too jarring.

<69> ALYSSA: For all my willingness to experiment and depart from anthropological convention there was still a tension between my wanting to be faithful to the memories of the people who donated the objects, and Selena wanting to free them up from their signifiers. I felt a responsibility towards my informants and my potential audience; I worried about the ways in which the animations could be read. A Romanian would most certainly recognize the objects as culturally specific, though there would still undoubtedly be a range of responses. [26] And what would non-Romanians think? Uncontextualized and unexplained, would these animations have any means of reaching a wider audience without utterly distorting their original associations? If they were left in such an open-ended state, I would be responsible for certain answers to which Selena was not professionally bound in the same sorts of ways.

<70> I became more and more convinced that the animations needed to be somehow "contained"; they couldn't just be floating, as the range of interpretation just seemed too dangerously wide. I felt the need to know that I was not just taking my informants' objects and flinging them into a completely inappropriate context that would not resonate with their own experience. Though a certain level of personal and ethical responsibility maintained throughout my fieldwork reassured me that this would not be the case, I resisted Selena's pull to relinquish the contextual information that was an integral part of my research process.

<71> SELENA: After much heated discussion and debate, and eventually through the course of writing this article, I suggested that we present the final work as a dual-screen installation.

<72> On opposing walls of a darkened room, two looped videos are playing. Projected on one wall is the series of interviews collected and filmed by Alyssa as part of her fieldwork, edited together to tell the "first person" stories elicited by the objects donated to her Memory Archive. Maintaining the look and feel of documentary, these accumulated stories serve as a collective memory bank for Romanians who lived through communist times. Simultaneously projected on the opposite wall are the 16mm animations of these objects, transferred to video. The subject of these animations is the feeling of memory itself, functioning as a contrapuntal dialogue between the artist and the interviewees.

<73> The interviews are heard in original Romanian, and they fill the exhibition space with sounds of this language. They are translated into English only as written subtitles. Re-created sounds of the animated objects (cloth rubbing against cloth, ice melting, metal clanking against wood) are also broadcast in the space, adding an aural, sensory accompaniment to both the animations and the interviews. The animations and the filmed interviews are not of the same duration: because they each are repeated on a loop, the combination of images appearing simultaneously on-screen is always different. This phenomenon allows for chance "montages" between the two sets of images and their corresponding sound tracks. The viewer, standing literally between the two screens, ultimately is required to create his or her own narratives from the simultaneously projected images. These generated narratives, like memory, are fragmentary and incomplete, depending on the part of the narrative cycle into which the viewer enters.

The Memory Archive

<74> ALYSSA: The idea of a split screen installation is not a common one among ethnographic filmmakers.[27] But for me it was a way to extend the somewhat restricted paradigm of the “ethnographic film.” Films made by anthropologists are often geared towards specific models allowing for a limited range of styles and presentations. As a visual anthropology student, I had been taught that most visual ethnographies fall into the category of either a “research film,” using the medium to analyze observable activities for the purposes of anthropological description, or an “ethnographic documentary,” generally using an observational approach, with a narrative structure both informed by and contributing to a broader anthropological investigation. [28] My different treatment of subject matter through this particular collaboration, however, demanded a different conceptualization of its presentation. In using a dual-screen format, I was freed from adhering to certain linear, narrative conventions, but still allowed important information from my interviews to be conveyed, while maintaining the sensory power of the animated objects.[29]

<75> It also seemed to be one of the only ways for both Selena and me to be true to our own perceptions of the field, while simultaneously acknowledging each other’s methods and expressions as equally legitimate. Selena’s presence in Bucharest was not just a matter of being absorbed into my pre-existing ethnographic work and “helping out” with it. Instead, she became personally implicated in the process, by placing herself, on her own terms, into the field that I had been inhabiting. Her contribution was not simply a “part” of my project, but rather an entity in its own right, an element of negotiation and dialogue with me and my own ideas about the project’s significance. Preserving both of our angles of perception, allowing them to be considered simultaneously and in relation to one another, also upholds the dynamic of our collaboration so that our voices do not blend into one, but rather engage with one another, sometimes listening, sometimes speaking over one other. Allowing space for both sets of perceptions challenges our audience to consider not just the material at hand, but also to think about what looking at something in different ways can entail.

<76> SELENA: Collaboration is by nature social, always involving shared activity and discussion, and prompting an active and sometimes risky exposure of each individual’s private ideas and instincts. It has challenged the habits and presuppositions of my own solitary studio practice; and it challenges one of the most deeply rooted historical assumptions of art making: the overarching, “sacred” importance of the subjective perceptions of the individual artist.

<77> There were many moments in my collaborative work with Alyssa when I could not explain the impetus behind one of my decisions. Why, for example, did I want to film melting ice cubes? Certain ideas coming from my own intuition (that an ice cube tray would be visually most powerful when seen as a vehicle for the transformation of matter, of ice into water) were not, understandably, immediately obvious to my collaborator. In engaging someone else in my own creative process, I had to constantly maneuver between following my impulses and externalizing or rationalizing their import. What does it mean to express and explain an idea before it has been fully developed or manifested? When does an idea shrivel in the light of the very words summoned to communicate its meaning?

Concluding Thoughts

<78> Both artists and anthropologists acknowledge the inability of any observer to “accurately” or “absolutely” represent reality. Yet the traditional goal of the anthropologist negotiating between the cultural object of study and the subjective distortions of interpretation, is still ultimately to communicate something about that object of study rather than to focus solely on the processes of individual perception (or misperception). The assumed role of the artist is quite different. It is precisely the fissures and gaps in the objective representations of reality that are valued.[30] As the artist Christian Boltanski has noted, “[Y]ou could say that painters have always sought either the ability to draw a perfect line or the means of capturing a given reality. But they inevitably fail, because one can never capture reality, any more than one can produce a perfectly straight line. For me, the unifying factor among artists is this failure, which is inescapable and almost desired, or at least anticipated” (Gumpert 1994: 171).[31] The particular subjectivity of the artist lies in his or her willingness to open up to this very fallibility, the acknowledgement that what we are left with, in the end, is an imperfect rendering of reality, as seen and projected through the lens of our own subjectivity.

<79> While artists may embrace (and even exploit) this “failure to capture reality” in their work, ethnographers are not encouraged to do so. Although certain anthropologists have called for more experimental approaches, urging their intellectual peers to visually challenge the “dominant narrative paradigms” entrenched in the field (Schneider 2008: 188), or to engage in artistic “ways of knowing” that “[sidestep] stable interpretations, explanations, and meanings” (Ravetz 2007b: 279), such tasks are much more easily said than done.[32] As Ravetz observes through her work in both disciplines, it is difficult to find a “middle ground” between being responsible to the experiences of one’s informants, and wanting simultaneously to convey the “partial and fleeting” aspects of meaning (Ravetz 2007a: 261). Except for certain types of museums, there are no immediately obvious settings to present such work.[33] While an analysis of the collaborative process may fit into an academic journal, a thesis chapter, or be presented at a conference, the resulting work itself has no established space to be considered and analyzed by members of both artistic and anthropological communities.[34] The project discussed in this paper, therefore, is intended not only to challenge particular ideas about how collaborative ethnographic and artistic practices should be conducted in the field; it also underscores the need for developing new arenas for such work to be “read” and perceived.

<80> By incorporating Selena’s practices into an anthropological context, this particular collaboration gave her the opportunity to situate concepts explored in her artistic oeuvre (memory, materiality, perception) within a specific cultural framework. Similarly, Alyssa’s involvement in the artistic side of the collaboration offered her a chance to place her particular ethnographic investigations (Romanian experiences of post-socialist transition) into wider, more universal structures.[35] We were thereby able to address the same basic subject matter by approaching it from opposite directions. This epistemological dynamic is reflected in the physical layout of our installation, with each screen projecting its own messages, but also receiving the form and contents of the images from the opposite side of the room. The process of working together and the product of our interactions has opened up the possibility of pushing such interdisciplinary engagements further, as well as offered both of us new ideas to pursue upon returning to our individual projects.

<81> The collisions between disciplinary approaches and their respective assumptions need not be viewed as leading to an irresolvable deadlock. Nor should they be understood as requiring compromises in which one side “gives in” to the rules or standards of the other. We interpret our collaboration not as the absorption of one discipline into another, or a “hybridization” of approaches, or even a mutual appropriation of meanings or activities, but rather as a productive, ongoing process of confrontation and negotiation. Through a combination of dialogue and practical experimentation, involving both rational and intuitive facilities, the apparent conflicts and tensions between the fields of art and anthropology are not so much reconciled as creatively exploited. Further experiments in this vein ideally will continue to expand upon approaches to palpably and materially rendering the substance of what is encountered in the field in new and unanticipated ways.

Acknowledgements

<82> Warm thanks to Amanda Ravetz and Arnd Schneider for their very detailed and perceptive comments on an earlier draft of this article. We are also grateful to Vibha Arora, Justin Scott-Coe, and Reconstruction’s anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. Thanks also to Tom Weaver from Hunter College, and those from the University of Manchester who gave their feedback, including Sarah Green, Andrew Irving, Sharon MacDonald, and the members of the post-graduate seminar in the department of Social Anthropology. We are appreciative of the useful input from Christoph Rippe and Cecilie Øien, as well as support from Nell Bădescu, Sorina Chiper, Alina Ciobănel, Fotinica Gliga, Monika Pădureţ, Zoltán Rostáş, Călin Torsan, Ioana Vlasiu, and all of the other Memory Object donors. The fieldwork and research for this paper was made possible through grants from the School of Social Sciences and the North American Foundation of the University of Manchester, and were additionally aided by funding from the Romanian Cultural Institute in Bucharest.

Works Cited

Asch, Timothy & Patsy Asch. 1988. “Film in Ethnographic Research.” In Cinematographic Theory and New Dimensions in Ethnographic Film. Paul Hockings & Yasuhiro Omori, eds. Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology.

Benjamin, Walter. 1999. The Arcades Project. Cambridge: The Belknap Press.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. 2002. Relational Aesthetics. Paris: Presses du réel. English edition translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods.

Buchli, Victor. 2000. An Archaeology of Socialism. Oxford: Berg.

Coles, Alex, ed. 2000a. Site-Specificity: The Ethnographic Turn, Vol. 4/ de-, dis-, ex-. London: Black Dog Publishing, Ltd.

---. 2000b. “An Ethnographer in the Field” (Interview with James Clifford). In Site-Specificity: The Ethnographic Turn, Vol. 4/ de-, dis-, ex-. London:

Black Dog Publishing, Ltd.

Crary, Jonathan. 2001. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Twentieth Century. London: The MIT Press.

Clifford, James. 1998. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

---. 1981. “On Ethnographic Surrealism.” In Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 23, pp. 539-564.

Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. Cambridge, UK: The University Press.

De Bromhead, Toni. 1996. Looking Two Ways: Documentary’s Relationship With Cinema and Reality. Hojbjerg, Denmark: Intervention Press.

Fentress, Paul & Chris Wickham. 1992. Social Memory. Oxford: Blackwell.

Foster, Hal. 1996. The Return of the Real: Avant-garde at the End of the Century. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

---. 1995. “The Artist as Ethnographer?” In The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology. George E. Marcus & Fred R. Meyers, eds. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

---. 1993. Compulsive Beauty. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Frisby, David. 1984. “The Flâneur in Social Theory.” In The Flâneur. Keith Tester, ed. New York: Routledge.

Graves-Brown, P.M. 2000. Matter, Materiality, and Modern Culture. London:Routledge.

Green, David & Peter Seddon, eds. 2000. History Painting Reassessed: The Representation of History in Contemporary Art. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Grimshaw, Anna & Amanda Ravetz. 2004. Visualizing Anthropology: Experimenting with Image-Based Ethnography. Bristol: Intellect Books.

Gumpert, Lynn. 1994. Christian Boltanski. Paris: Flammarion Press.

Harrison, Charles & Paul Wood, eds. 1993. Art in Theory: 1900-2000. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Henare, Amiria, Martin Holbraad & Sari Wastell, eds. 2007. Thinking Through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically. London: Routledge.

Humphrey, Caroline. 2005. “Ideology in Infrastructure: Architecture and Soviet Imagination.” In The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (11), pp. 39-58.

Kelly, Julia. 2007. Art, Ethnography, and the Life of Objects: Paris c. 1925-35. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Leiris, Michel. 1929. “Dictionaire Critique: Metamorphosis,” in Documents 6 (November).

MacDougall, David. 2006. The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography, and the Senses. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

---. 1999. “Social Aesthetics and the Doon School.” In Visual Anthropology Review, Vol. 15, Nr. 1, Spring-Summer, pp. 3-19.

Marcus, George & Fred Meyers, eds. 1995. The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

McClancy, Jeremy. 1997. Contesting Art: Art, Politics and Identity in the Modern World. Oxford: Berg.

Melchert, Norman. 1995. The Great Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy, Second Edition. London: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Merewether, Charles. 2006. The Archive. London: Whitechapel Press.

Monahan, Laurie. 2004. “Rock, Paper, Scissors.” In October 107 (Winter), pp. 95- 114.

Pink, Sarah, Lazslo Kurti & Ana Isabel Afonso, eds. 2004. Working Images: Visual Research and Representation in Ethnography. London: Routledge.

Postma, Metje. 2006. “From Description to Narrative: What’s Left of Ethnography?”

In Reflecting Visual Ethnography—Using The Camera in Anthropological

Research. Metje Postma & Peter Ian Crawford, eds. Leiden: CNWS

Publications; and Højbjerg, Denmark: Intervention Press.

Ravetz, Amanda. 2007a. “From Documenting Culture to Experimenting with Cultural Phenomena: Using Fine Art Pedagogies with Visual Anthropology Students.” In Creativity and Cultural Improvisation. Elizabeth Hallam & Tim Ingold,

eds. Oxford: Berg (in press).

---. 2007b. “A Weight of Meaninglessness about Which There is Nothing Insignificant: Abjection and Knowing in an Art School and On a Housing Estate.” In Ways of Knowing: Anthropological Approaches to Crafting Experience and Knowledge. Mark Harris, ed. Oxford: Bergahn Books.

Reid, Susan E. & David Crowley, eds. Style and Socialism: Modernity and Material Culture in Post-War Eastern Europe. Oxford: Berg.

Ruby, Jay. 2000. Picturing Culture: Explorations of Film and Anthropology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Schneider, Arnd. 2008. “Three Modes of Experimentation with Art and Ethnography.” In The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (14), pp. 171-194.

---. 2006. “Appropriations.” In Contemporary Art and Anthropology. Arnd Schneider & Chris Wright, eds. Oxford: Berg.

---. 1993. “The Art Diviners.” In Anthropology Today, Vol. 9, No. 2(April), pp. 3-9.

--- & Chris Wright, eds. 2006. Contemporary Art and Anthropology. Oxford: Berg.

Schwenger, Peter. 2006. The Tears of Things: Melancholy and Physical Objects. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Stiles, Kristine. 2005. “Remembrance, Resistance, Reconstruction: The Social Value of Lia and Dan Perjovschis’s Art.” In Marius Babias, ed. European Influenza. Venice: Romanian Pavillion, La Biennale de Venezia, 51. Esposizione Internazionale D’Arte, pp. 574-612.

Stoller, Paul. 1989. The Taste of Ethnographic Things: The Senses in Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Svašek, Maruška. 2007. Anthropology, Art and Cultural Production: Histories, Themes, Perspectives. London: Pluto Press.

Taussig, Michael. 1992. “Tactility and Distraction.” In Rereading Cultural Anthropology. George E. Marcus, ed. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Verdery, Katherine. 1996. What Was Socialism, and What Comes Next? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Weigel, Sigrid. 1996. Body and Image Space: Re-reading Walter Benjamin. Translated by Georgina Paul, with Rachel McNicholl & Jeremy Gaines.

London: Routledge.

Yates, Francis. 1966. The Art of Memory. London: Routledge and K. Paul.

Notes

[1] Cited in Monahan (2004: 95). [^]

[2] As Arnd Schneider writes, “appropriation” can be seen as one of the defining tropes characterizing the relationship between the two disciplines, a post-modern action of “challenging notions of exclusive authorship” and “retrieving and recreating meaning” across historical and cultural contexts (2006: 37). [^]

[3] My own practices of filming in the field have been influenced by my training at the University of Manchester’s Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology from 2004 to the present. Here students are taught all aspects of the production process, from filming to sound-recording to editing, and we usually work on our own or in pairs, without large crews. We are also strongly encouraged to adopt an observational approach to filming, employing techniques that involve following rather than directing the action, avoiding conventional interview situations, and using the images, rather than voice-over narration or external commentary, to structure the film. As I will discuss below, I have both adhered to and departed from these principles in my own work [-A.G.]. [^]

[4] As Amanda Ravetz has noted (personal communication), because the subject of the experience of sensory perception is extremely difficult to access, anthropologists have tended to steer away from it (with the notable exceptions of W.H.R. Rivers, Gregory Bateson, Nigel Rapport, and more recently, Andrew Irving). [^]

[5] While neither discipline can be viewed as definitive or delimited, acknowledging these historically contingent and constructed boundaries (even if they are fluid, or not always respected) can be helpful in initially demarcating and defining each realm, in order to more clearly pinpoint their overlaps and divergences. [^]

[6] For detailed analyses of innovative and important anthropological/artistic works by Juan Downey, Sharon Lockhart, and Michael Oppitz, see Schneider (2008). [^]

[7] Boltanski in particular blurs the boundaries between fact, fiction, art, and science in his work. His use of archival sources, such as newspaper clippings, photographs, and found objects mines sources of what is often considered “anthropological” data, in order to reconstruct his own biography in the form of an ongoing, continually re-invented museum display. [^]

[8] Visual anthropologists’ explorations of “social aesthetics” provide insights into the cultural relationships between individuals and their sensory environments and the emotional impacts of peoples’ physical and material surroundings (MacDougall 1999), which can be connected to broader anthropological investigations of the links between aesthetics and politics. While many social scientists no longer claim a straightforwardly functionalist or deterministic connection between materiality and culture (Buchli 2000; Graves-Brown 2000; Humphrey 2005; Reid and Crowley 2000), the precise nature of the relationship between ideology and aesthetics in post-socialist arenas deserves closer attention. [^]

[9] Images serve as the basis for many different theories of memory. Roman orators were trained to mentally attach images of places and objects to their texts, in order to facilitate the process of semantic recall (Fentress and Wickham 1992; Yates 1966). Aristotle’s writings describe the act of recollection as picturing an image in one’s mind (Weigel 1996: 148). Walter Benjamin conceptualized memories as “thought-images,” which enter the body to become “body-spaces,” existing in individual and collective minds, as well as in public material forms (Weigel 1996: 153). [^]