Reconstruction 9.1 (2009)

Return to Contents>>

Making Theatre-Making: Fieldwork, rehearsal and performance-preparation [1]/ Kate Rossmanith

Abstract:

In a large rented room in Sydney, Australia, on hot January days, a small group of practitioners have only three weeks to rehearse for a large production. 'Let's run that scene again. Let's just push through,” I hear them say over and over. As metaphors, ‘running' and ‘pushing' are not only articulated verbally, but the movement within the space and the presence of the Realpolitik of production create an adrenaline-like pulse. The director spends rehearsals barefoot with an unlit cigarette in his hand, which he might use as a bookmark or he shoves it behind his ear or plays with it in his hands. When actors rehearse a scene on the taped-out set, the director watches, perched on a corner of a chair, with his bodyweight suspended between a full sit and a stand, ready to leap up at any moment.

This excerpt documents the frantic pace of a professional theatre rehearsal. Taken from my field notes, it is part of an enquiry into practitioners' engagement with, and experience of, performance-making practices. Drawing on a decade of case studies, this essay maps out the ways in which fieldwork approaches – and critical ethnography in particular – can be put to use to better understand the rehearsal work of professional performers, directors and production teams.

<1> In his colourful account of preparations for the National Theatre's 1980 production of Bertolt Brecht's Galileo, Jim Hiley describes the process of rehearsal: "Comedy and tragedy against a background of slog: this is the reality of theatre at work" (1981: x-xi). Hiley describes skirmishes over who might direct the show, how actors are chastised for forgetting their moves, as well as the often mundane daily practice involved in discussing scenes, shaping bits of dialogue and action, and arranging costume fittings. But the terms "comedy", "tragedy" and "slog" are equally suitable descriptions for the labours of fieldwork and writing. The practice of participant observation over a sustained period of time, and the period of analysis and writing that follows, constitute intense work. This applies not only to traditional anthropological fieldwork undertaken in cultural worlds radically different from the researcher, but also to the fieldwork we conduct in our own social and cultural backyards. A fieldworker doesn't need to get her boots muddy to find herself deep in the mess of fieldnotes, interview material, and half-formed analyses.

<2> I am one of several Australian performance studies scholars who, for at least two decades, have been developing participant-observation methods to study and write about professional performance-making practices. Performance Studies, a discipline that emerged out of North America in the 1960s, originally positioned itself somewhere between "theatre" and "anthropology", with special interest in ideas of ritual and intercultural performance. Inspired by thinkers such as Erving Goffman, notably his work in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959) and Frame Analysis (1974), Performance Studies concerns itself in part with the broad spectrum of performance, from highly framed performance events (opera, Noh Theatre, dance) through to everyday performances. (My recent research, for example, studies the ways in which people in north Australia learn to live with crocodiles, and how they come to enact a "living-with-crocs" in their movements and behaviour.) Nowadays Performance Studies is profoundly interdisciplinary, drawing on thinking from areas such as architecture and law, through to biology and tourism studies [2]. This article, however, focuses on a relatively small and emerging sub-discipline of performance studies-–rehearsal studies -–and, specifically, what might be involved in conducting fieldwork and analyses in this area [3].

<3> Those scholars adopting a participant-observation approach to study rehearsals sit in on weeks and months of professional rehearsals, taking notes about what people say and do, conducting interviews, and collecting supporting material (scripts, photographs, budgets, and company histories-–material that may make up the appendix of a rehearsal analysis). Some also video-record rehearsals, but the amount of data produced from such a method is huge, and those researchers using such recording techniques have been forced to grapple with how to edit the material (see McAuley 1998). Depending on the scale and type of production-– opera, dance, state-subsidised theatre, community theatre, contemporary performance, movement-based work, one-person shows, self-devised pieces-–rehearsals may include the following "roles": directors, producers, actors, performers, playwrights, musicians, stage managers, designers (set, costume, lighting, sound), composers, dramaturges, choreographers, puppeteers, voice coaches, and 3D-technicians. And often practitioners will opt not to use the term "rehearse" -– a term traditionally associated with mainstream, text-based theatre (for a discussion of the etymology of "rehearse", see Cole 1992: 4)-–and will instead use "workshop" or "devising process". My use of the term "performance-preparation" in the title of this article is meant to capture that work that sees itself outside/apart from traditional rehearsal practice: work, for example, self-devised, often physical-based, as opposed to the rehearsing of a pre-existing playscript.

<4> A decade ago, rehearsal studies pioneer Gay McAuley recognised that the documentation and analysis of a rehearsal process "has much in common with the work of the field ethnographer" (1998: 77), and that she and her colleagues were following "albeit unconsciously in the early days, the ethnographic model of participant observation" (1998: 77). She points out that, like ethnographers in the field, academic observers in the rehearsal room can be positioned by their hosts; they may be shown what their hosts think they want to see; and they may be shown only what is thought appropriate to show an outsider (1998: 77). Since McAuley's publication, several scholars have written, and taught, on the usefulness of ethnographic-like approaches to the study of rehearsal (see Rossmanith 2004, 2006, 2008b; Ginters 2006).

<5> In this article I explore what an ethnographic-like fieldwork approach offers rehearsal studies and how a would-be student observer might go about undertaking such research. My use of the term "ethnography" and "fieldwork" is meant to be analogous, not homologous to the way such terms are used in anthropology and other fieldwork-based disciplines. I'm not suggesting that spending months in a rehearsal room is just like spending years in a radically different cultural world. Firstly, while they may be newcomers to rehearsal and performance, rehearsal observers are, on the whole, insiders to the cultural world within which rehearsals take place. Whereas researchers studying in foreign places work hard to familiarise themselves with new practices, ways of being, and cosmologies, rehearsal observers must at times struggle for distance and suspend their own taken-for-granted knowledges, instead engaging with how practitioners make sense of what they themselves are doing. Secondly, the rehearsal process itself is almost always a clearly delineated period of time. Whereas ethnographers must often arbitrarily bracket off the ethnographic present-– the specific time studied-– most rehearsal processes have a natural arc: a set period of preparation leading up to a performance. Even if a production has been in development for many years, the goal for the practitioners is to see that development into a performance. Of course, that is not to say that rehearsals are experienced by practitioners and observers as an arc. Actor Simon Callow describes rehearsal processes as "halting" (1984: 162), and Susan Letzler Cole acknowledges that "[t]he work of rehearsal work-–what, in fact, often makes actors irritable and frustrated-–is the forced enactment of the flow and the stoppages" (1992: 9).

<6> Instead of claiming that studying rehearsal is just like conducting ethnography (which in itself is not a defined body of thought or a systematic set of practices), I am asking: What knowledges about performance-making can be generated by conducting an ethnographic investigation, with its emphasis on time spent with social agents? I also offer the ‘how' of fieldwork practice in the context of such an enquiry: How do you conduct rehearsal fieldwork? How do you organise data? What questions should you ask of your fieldnotes? How do you deal with your own position in the process? How do you move toward a rehearsal analysis?

<7> Rehearsal analyses are more than simply an account of things said and done; they not only explain the nuts of bolts of what it was to put a show together, but they attempt to make sense of the way that practitioners made sense of the work in which they were engaged. When reflecting on much of her early rehearsal research, McAuley (1998) writes that her preoccupation focussed on studying the creative decisions that led to the final performance, thus contributing, for instance, to the project of performance semiotics: how practitioners construct "signs" for an audience. More recent work has both widened and tightened the focus to include the details of working practice, how practitioners understand and experience their own practice, and the social and cultural world in which rehearsals happen. In the Department of Performance Studies at the University of Sydney, for example, there are more than 60 casebooks written by honours students, including productions of drama, opera, dance, physical theatre, community-based and group devised work (McAuley 2006: 9), as well as a number of postgraduate theses. Such work is distinct from popular accounts of rehearsal such as David Selbourne's The Making of a Midsummer Night's Dream (1982), Hiley's Theatre At Work (1981), Cole's Directors in Rehearsal (1992) and Playwrights in Rehearsal (2001), as these accounts focus on chronology -"what happened"–rather than analysis, such as asking "In what ways was ‘what happened'meaningful to the practitioners?" Analyses tend to take a more synoptic perspective. It is also distinct from popular diarised accounts of rehearsal, like Anthony Sher's The Year of the King (1985), Simon Callow's Being an Actor (1984), and Max Stafford-Clark's Letters to George (1989), which, while invaluable regarding insights into practitioners' experiences, cannot offer the sorts of insights that a researcher not directly involved in rehearsals might provide.

<8> This article is about making theatre-making, both in terms of the ways in which practitioners make theatre over weeks and months of rehearsal, as well as how researchers "make theatre-making" by developing and refining their approaches to studying rehearsal practice. At its core, it is a consolidation of material we teach students, and a response to questions frequently asked by those students as they embark on rehearsal fieldwork and their subsequent construction of rehearsal analyses. In a sense, it is intended as a how-to guide for student researchers-–and others-–interested in studying rehearsal using a participant observation approach. I have written it as a means to formally articulate research practices that have circulated informally amongst rehearsal studies scholars.

Why ethnography?

<9> Jim Hiley (1981) and Brian Cox (1992), who have both written rehearsal accounts of productions, each refer to their work as being a "story". So it is to a story I now turn – specifically, excerpts conjuring the "ethnographic present" of my own field research I conducted in the late 1990s in Sydney, Australia.

At 9pm on a weeknight, in a drafty, cavernous rehearsal room in late Autumn, four actors and a director work together on the playscript, The Season At Sarsaparilla, by playwright and novelist, Patrick White, winner of the 1973 Nobel Prize for Literature. They sit around a large wooden table, discuss their characters, analyse the dialogue to "find the meanings" of exchanges and scenes. Then they move up into the floor space, a make-shift stage marked out with masking tape, the key set pieces indicated by white crosses and long white lines. Rebecca, a thick-limbed, feisty actress, clasps in her hand a folder containing the script, and, as she paces the stage space, she glances down regularly to view and register her lines. She is playing the role of Judy, an innocent, whimsical teenager. Despite Rebecca's gothic clothes and rough hair, she is committed to evoking the character and the scene, and to delivering White's poetic prose. And then she drops her script. As the folder falls from her hands, it scatters pages across the floorboards. Her own face stares up at her: Rebecca's black-and-white headshot–-the large glossy photograph actors use to secure an agent and chase auditions–-betrays her ambition to the group. She blushes as the director jumps up and scoops the photo off the floor so that the scene might continue uninterrupted.

Fieldnotes for The Season At Sarsaparilla

Kate Rossmanith, 1997.

"We are an ensemble theatre and there are no stars except the play."

New Theatre Membership Booklet

These two excerpts, sitting side-by-side, reveal the extent to which the discourses and practices in which practitioners are engaged in over days, weeks and months, and their experiences of rehearsing, are inextricably embedded in rich and complex contexts. It is not sufficient to understand rehearsal processes solely in terms of actors and directors shaping lines and scenes. For example, at New Theatre in Sydney in the 1990s, actors, directors, administrators and crewmembers were often situated inside several competing discourses as to what constituted "real" theatre. The process of "making theatre" was, for them, overtly about egalitarianism, where everyone worked for free, where, as the booklet put it, "there are no stars except the play". At the same time, people's ambitions were alive and present but rarely spoken about. Rebecca's headshot was not only an incursion into the "fictional world" that was being created through the scene run; it was a foregrounding of a dimension of these rehearsals that was taboo to discuss.

<10> Ethnographic-like fieldwork offers rehearsal studies ways to consider how theatre rehearsal and people's lives are intertwined, allowing for an investigation of the ways in which rehearsal was meaningful to practitioners. Rather than researchers relying on acting theories to offer insight into rehearsal (the pitfalls of which I address in Rossmanith 2008b), fieldwork allows for a study of rehearsal as it occurs in lived bodies, with all the unpredictability and complexity that accompanies real people. It allows for the documenting-–indeed, the experiencing–-of working conditions, of the heat, the cold, the pace of practice. As Dwight Conquergood writes: "Ethnography is an embodied practice. It is an intensely sensuous way of knowing" (1991: 180).

<11> Participant observation also has a unique capacity, for example, to reveal the layers of discourse used by practitioners as they engage in their work. With its emphasis on what Judith Okely calls "graphic scrutiny" (1996: 17), and with the researcher's relative distance, it is possible, as Georgina Born (1995) points out, to discern between a discourse about a field and a discourse within a field. In Rationalizing Culture, her ethnography on the Parisian institute IRCAM, Born recognises that the way that social agents describe a cultural world to someone outside that world will differ from the discourses that operate within that cultural sphere. In rehearsals for New Theatre, for instance, a very explicit discourse of "community" and "egalitarianism" operated, circulating in promotional material and in interviews. At the same time, a less conscious discourse of "career building" was also evident as artists whispered amongst themselves about who was "winning" jobs, and they used productions to secure agent representation and more prominent positions in the theatre scene (Rossmanith 2004).

<12> This points to the particular knowledges available to participant observers who are not directly involved in the production. For it is the case that the practitioners' own practices and discourses may not be transparent to those practitioners. In my own work, I have extended Born's observation to recognise that rehearsal fieldwork offers the potential for the researcher to discern between a conscious discourse about a practice and a less conscious discourse within a practice (Rossmanith 2008b), a distinction I shall return to later. This is why it is not satisfactory to rely alone on interviews with practitioners for insights about rehearsal: interviewees can only ever offer particular knowledges, namely conscious discourses about practice. As researchers we want to get at the (less conscious) talk embedded in those practices, as well as to encounter those practices firsthand. Fieldwork allows researchers to tease out the different types of knowledges at play for practitioners. In an effort to rescue the logics of bodily practice from a framework of purely propositional knowledge, anthropologist, Michael Jackson, suggests that: "the meaning of practical knowledge lies in what is accomplished through it, not in what conceptual order may be said to underlie or precede it" (1996: 34).

Transactional Analysis: rehearsal and psychology

<13> By way of a counterpoint to a participant observation approach to studying rehearsal, and therefore as a way to further foreground the merits of such an approach, I want to briefly consider a very different empirical approach to researching rehearsal. In the early 1970s, psychology-based research on theatre rehearsal emerged. At the time, cognitive-behaviourist psychology was a relatively recent research paradigm, and Bowling Green State University in Ohio, USA, founded a journal, Empirical Research in Theatre, that acted as a point of intersection between this new paradigm and theatre studies. In 1973, three academics, Roger Hite, Jackie Czerepinski and Dean Anderson, authored the paper ‘Transactional Analysis: A New Perspective for the Theatre' that would influence developments in one area of rehearsal research for at least the following fifteen years. Borrowing transactional analysis theory--a psychology paradigm predicated on the assumption that humans have a basic biological need to interact with other humans--these writers transposed the framework into a theatre studies context. In their paper, they suggest that transactional analysis might assist dramatic criticism because it might go some way not only in explaining character interaction in a play but also the playwright's "ego states" (1973: 8) that may have prompted him to write the play in the first place. But the most productive contribution for the generation of future work concerned theories of rehearsal interaction between directors and actors. While the intersection of these two paradigms---theatre studies and this particular model of psychology---might initially seem appealing and may even seem an obvious research direction, the methodology is problematic.

<14> Hite, Czerepinski and Anderson's "experiment" involved teaching a university group of directors and actors a basic understanding of transactional theory (through lectures, improvisations and discussions) which they then used to discuss the "psychological and motivational aspects of the production" (1973: 13). This theory was also used to "manage" the

interpersonal transactions that occur between director and actors. If the director is aware of the ego state of his [sic] actors, he is in a better position to maintain complementary transactions and to avoid many personality clashes that frequently arise from the heat of rehearsals. (1973: 14).

This thinking provided the groundwork for future studies, including Robert Porter's paper ‘Analyzing Rehearsal Interaction' (1975), and Stratos E. Constantinidis' paper ‘Rehearsal as a Subsystem: Transactional Analysis and Role Research' (1988) (see also Miller and Bahs 1974).

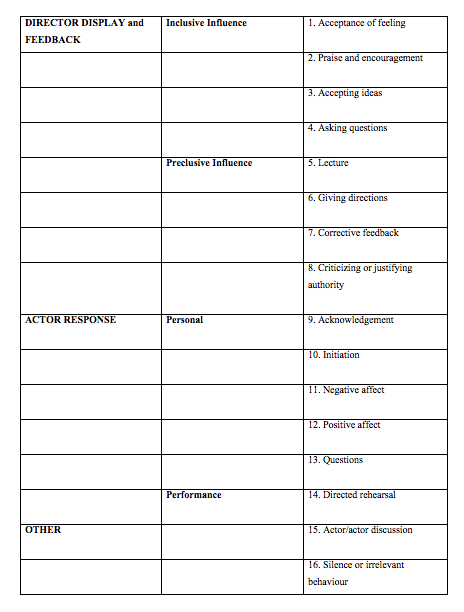

<15> Drawing heavily on transactional analysis and on techniques widely used in education research, Porter (1975) offers a model of verbal interaction between actors and directors during rehearsal. His work is steeped in a number of explicit assumptions concerning actor/director roles and relations. These assumptions---based on the understanding that rehearsal is a teaching/learning process---are outlined under what he terms "A Rehearsal Paradigm": "the director influences the actors in such a way as to effect a desired change in their behaviour" (1975: 4); "the actor experiences a teaching force exerted through the manipulation of stimuli and reinforcements" (1975: 4); "In setting the objectives for each rehearsal, in lecturing and giving directions, in soliciting actor opinions, in praising or criticizing, in accepting or rejecting actor ideas and feelings, the director is the key agent in the rehearsal drama" (1975: 4). He establishes a binary between what he understands as the restrictive director (adopting an autocratic style) and the permissive director (who "encourages maximum freedom for exploration and self-discovery" [1975: 5]), and he investigates the effects of these two directing styles by developing a framework to study actor/director interaction: an Observational System of Rehearsal Interaction Categories (OSRIC) (see figure 1).

<16> Porter provides summaries of the categories. For instance, "Acceptance of Feeling" is "when the director says he understands how the actor feels or implies that the actor has the right to express both positive and negative feelings... when the director expresses interest or concern for the emotional well-being of the actor." "Initiation" (a subcategory of "Actor Response") is "when the actor makes a statement or contributes an idea that is not called for by the director" (1975: 13). "Other" includes "Actor/Actor Discussion" ("problem-solving talk among actors under the director's supervision") and "Silence or Irrelevant Behaviour" ("all non-functional periods of general talk or of silence which is unrelated to the purpose of rehearsal") (1975: 15). As in the earlier transactional analysis research, Porter uses a university group of actors and directors, although at no stage does he clarify who the participants are exactly or where the experiments were conducted. Porter trained rehearsal observers in OSRIC, and, during rehearsal, they coded interaction every three seconds.

Figure 1, An Observational System of Rehearsal Interaction Categories (OSRIC)

The codes were used to produce a "General Matrix Analysis" involving three indexes:

1. Interaction Index: the amount of director/actor interaction with the total time spent in the rehearsal session;

2. Director/Actor Ratio: the extent to which either dominated discussion;

3. Director Influence Ratio: "This index is a precise measure of the extent to which any given director can be said to use a blend of the two styles [inclusive and preclusive directing]" (1975: 20).

<17> In 1988, fifteen years after the original "transactional analysis" article was published, Constantinidis wrote a paper investigating "the director/actor interaction in order to understand the real leadership-style properties of the rehearsal process" and, secondly, "the ways an actor carries out a role" (1988: 66). He understands the results as producing what he calls a "subsystem" of rehearsal, where the "logocentric" nature of what he sees as the "traditional" model of rehearsal is challenged (1988: 64). Constantinidis draws on both Porter's work as well as Suzanne Trauth's paper (1980) in order to examine "permissive and restrictive rehearsal communication systems in actor task involvement and rehearsal atmosphere" (1988: 67). Rather than conducting his own experiments as per Porter and Trauth, Constantinidis borrows their psychology-based frameworks and their research findings, and he collects accounts of rehearsals to hypothesise what might have been the "transaction" characteristics of, for instance, Jerzy Grotowski's rehearsals, Peter Brook's rehearsals and rehearsals that actor and director, Joseph Chaikin, has been involved in. Constantinidis uses this same method to examine what he terms "actor's role-acquisition strategies" (1988: 69), drawing on psychology-based research results (he cites Powers et al. 1980) in order to rethink the acting approaches expounded by prominent theatre practitioners and theorists, Constantin Stanislavski, Bertolt Brecht, Vsevolod Meyerhold, Jerzy Grotowski and Antonin Artaud.

<18> The attraction these theatre academics had to cognitive-behaviourist research approaches is understandable: here was a model for empirical research that would produce reams of seemingly hard data. The possibilities of experiments seemed limitless. However, these methodologies are highly problematic, as the explicit teacher/student framework---with the all-knowing director and the infantilised actor---leaves no room for more nuanced interpretations of director/actor exchanges. Moreover, the "subjects" become radically pathologised to the extent that experiments on rats are used as the basis of research designs. Keith A. Miller and Clarence W. Bahs, in their paper "Director Expectancy and Actor Effectiveness" (1974), actually cite the following article: "The Effect of Experimenter Bias on the Performance of the Albino Rat" (R. Rosenthal and K. L. Fode, 1963). Divorced from any socio-cultural and historical context--we are not even given details about the participants---this research presumes the existence and the quantifiability of a universal human condition. This emphasis on what can be calculated or measured is reflected in the preoccupation with verbal interaction at the expense of everything else. Porter's work powerfully manifests this by including the oddly juxtaposed terms in one of his subcategories---"Silent or Irrelevant Behaviour"---and by limiting the coding categories to suit the academics' abilities to record "interaction". He writes: "It was found that observer reliability fell off rapidly when the number of categories exceeded sixteen... therefore it seemed advisable to sacrifice sensitivity for accuracy" (1975: 127).

<19> This approach to studying rehearsal slips into an uncritical celebration of the measurability of human behaviour. An ethnographically-oriented participant observation approach, however, acknowledges that the "subjects" involved are real people, that the researcher him/herself is a real person too, and that, as ethnographer Kirsten Hastrup writes, the emphasis should be on dealing with the world between ourselves and the others (1992: 116-33). As I have written elsewhere, my fieldwork diaries, and subsequent analyses, document the self-conscious practices of artists as they draw on sign systems of set, costume, gesture, voice, movement, and so on. Crucially, they also document "the less conscious construction of selves in the rehearsal room, figurings of textuality and authorship, and the Realpolitik of production" (Rossmanith 2006: 78). There is also

a dimension of embodied experience, where practitioners' knowledges operated at the level somehow distinct from a purely cognitive realm of understanding: rehearsals were experienced not only in terms of ‘understanding' but also in terms of ‘sensing' and bodily affect (Rossmanith 2006: 78).

Participant Observation: Entering the hidden world

<20> If Day One of rehearsals is daunting for directors and actors, it is perhaps more so for researchers new to participant-observation rehearsal fieldwork. While they may have undertaken preliminary study-– sitting in, for example, on design meetings-–the first day of rehearsals proper brings with it heightened nerves and anticipation. This is despite the fact that, in most cases, the researcher has arranged the rehearsal observation through a professional contact he or she has in the industry, and therefore will often know one or more of the practitioners. My own rehearsal documentation has always proceeded that way-–through contacts made from friends and friends-of-friends (obviously ethics clearance from the tertiary institution is still required prior to fieldwork).

<21> The main reason why rehearsal researchers rely on contacts to secure placements is that rehearsal is traditionally a carefully guarded and protected place of work. Rehearsal observer, Susan Letzler Cole, describes rehearsals as "a hidden world" (1992: 3), and it can feel just that: a private space where, to be given access, is an enormous privilege. In fact, several of the rehearsal processes I have observed have taken place behind locked doors. To reach rehearsals for one production, we were required to venture down the tight narrow side of the building to the stage door, before knocking loudly until someone traipsed downstairs to let us in. The experience-– on cold nights, in a dark passageway, facing a locked door–-reminded me of an early twentieth-century speak-easy: only a privileged few knew the location, and only the further privileged could gain access. In another rehearsal process, practitioners rehearsed on hot days on the third floor of a school building, with the windows of the room wide open, and the heavy traffic noise rendered our knocking on doors futile. Instead, whenever we wanted to be let into the building, we yelled up to the windows so that someone might come down and unlock the door. McAuley writes that "[t]he stage door is the physical manifestation of the demarcation between the world at large and the ‘secret kingdom' of the theatre practitioners, between public and private, between outside and inside" (1999: 67)-– which is why observer, Jim Hiley, was delighted that he was able to "roam unchaperoned" (1981: x) inside the National Theatre.

Figure 2, New Theatre in Newtown, Sydney. To the left of the theatre building is the narrow alleyway.

<22> Many rehearsal studies students ask the same question: once inside the rehearsal room, what do we write? Obviously they will have conducted preliminary research about the theatre group in question, the play text (if there is one), and perhaps even the training institutions where the practitioners studied. Having read some critical ethnography, and having observed and studied numerous rehearsal processes, I have developed organising tools I carry with me when taking notes. These revolve around place/space, time, bodies/movement, dialogue, as well as macro-institutional contexts. On my way to the first rehearsal, I reflect upon the sorts of knowledges and, therefore, expectations I carry with me: If a play script is being used, am I familiar with it? What do I know of the practitioners, the theatre company, and the place where they will rehearse? What is the performance genre they might be working in: naturalism or physical theatre or post-dramatic theatre? Upon entering the rehearsal space, and allowing practitioners to seat me where they wish, the questions I ask myself include: Where are we? What area are we in? What kind of building are we in? What does the room look, taste, feel, and smell like? Is it hot, cold, muggy, and windy? How is the space laid out? What time of day is it? How are the practitioners framing what it is they are doing? After several days, I begin asking other questions: What are the practitioners' experiences of time? How does this relate to the minutes on the clock? Who are these practitioners? What do they wear? How do they speak? What is it to move around in this room? How do bodies use this place, and how does the place "embed" itself in bodies (Casey 2001)? What are people doing? How do people talk about what it is they are doing? What are people being paid? Who is paying them? What is the production budget? Who is conducting the administration?

<23> Of course these questions are not exhaustive, but they provide a platform for further questions. Many of them have been developed over anomalies I encountered when observing rehearsals. For example, when comparing two rehearsal processes, I was amazed to discover that practitioners' experiences of time did not necessarily relate to the minutes on the clock. One group engaged in a very explicit discourse of "time running out", and they worked at a frantic pace, speaking fast, moving quickly, telling one another that they "just had to push through". Another group, however, rarely spoke about time at all, and their rehearsals had a slow, deliberate pace about them. This is despite that fact that the first group had more days and hours to rehearse than the second, and their production was shorter and was less complicated in terms of cast size and dialogue (see Rossmanith 2004). Similarly, the role of rehearsal places in rehearsals often extends beyond providing somewhere to work. McAuley (1999), Rossmanith (2004) and Filmer (2006) have shown the ways in which aspects of rehearsal rooms embed themselves in practitioners. For example, the rehearsals for one process I documented took place in a third storey room with high ceilings and huge arch windows that let in bright blue summer skies. Whenever there was a break, or when actors weren't directly required on set, people stood at these windows and gazed out. It was no surprise then when an actor asked the director if he could change his physical movement on stage "because I think I get up to look out the window", he said of his character. From then on, in that moment onstage, the actor would rise from the couch and come forward to stare out of a fictional window (Rossmanith 2004: 75-6).

<24> As I encourage note-taking skills in students, I explain to them that they must adopt the sensibility of a novelist–-not in the sense of fictionalising their encounters, but by developing the practices of keen observation and description. I also warn them that fieldwork can feel tedious and extremely uncomfortable at times, for we observers are usually politely glued to one chair as practitioners move around us. (Observer, David Selbourne, writing about rehearsals for Peter Brook's famous production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, complains of being stuck to his metal chair [1985: 153].) Many times I have ached to stretch my back and legs, only to stay still until a scheduled break. The challenge is to remain looking interested as the energy in the room is affected by everyone – including the (usually) silent observer in the corner. I tell students to ensure their faces relax into a faint smile whenever they are watching practitioners work. Australian director, Lindy Davies, insists that her performers must carry with them "unconditional positive regard", and this extends to documenters also, as our presence impacts in ways we cannot imagine (see Ginters 2006: 56). Whenever I have observed rehearsals, the practitioners, whether they realise it or not, turn me into a spectator for the production. They usually orientate their bodies towards me, glance over to see how I have responded to a scene or a moment, and even ask me quite explicitly whether a creative decision "works" or not (see Rossmanith 2004). I always try to be as positive and very general in my response, as I am more interested in the ways in which directors and performers are talking about their work than my own opinion of the creative merit of what it is they are doing.

<25> I divide my notes into "field jottings", and "field notes". Jottings involve the scrawled notes I take on-the-fly while watching rehearsals, always with the time written next to them, with bits of dialogue, with mini-sketches of the space, blocking, and with my own half-formed questions and thoughts. As I say to students, the process of taking jottings feels un-academic. You often feel as if what you are scribbling down is obvious, mundane, and, at the end of each day, you always feel as if you have not taken down enough – and certainly nothing clever. But this is the process of field jottings. You are painstakingly gathering piles of details and thoughts before building an analysis. Indeed the seemingly banal process of jottings is especially exposed when practitioners themselves take a look at what you are writing. Many times actors and directors might take a peek at my notebook or boldly request to read what I have written. After glancing through a couple pages, I am usually met with the comment: "You're just writing down everything that is happening. Aren't you bored?"

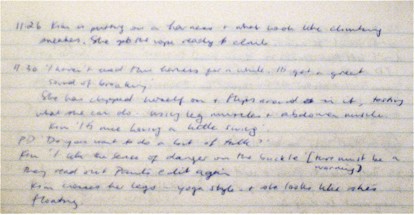

<26> Below is an example of field jottings I took in 2007 for the Australian production of Deeply Offensive and Utterly Untrue, created by the performance team, version 1.0. The show was self-devised, with the practitioners describing it as "an inquiry into the inquiry into the Australian Wheat Board Scandal". It was based on the transcript of an inquiry that was held into the Australian Wheat Board after the board was found to have used UN funds to indirectly pay bribes to Iraqi officials (for further information about the inquiry, see Overington 2007).

Figure 3, a section from my notebook (see below for transcription).

11.30 ‘I haven't used the harness for a while. It's got a great sound of breaking'.

She has clipped herself on + flips around in it, testing what she can do. Using leg muscles + abdomen muscles.

Kim [sic] ‘It's nice having a little swing'

PD [Paul Dwyer, dramaturg] ‘Do you want to do a bit of talk?'

Kim ‘I like the sense of danger on the buckle' [there must be a warning]

They read out Paul's edit again

Kim crosses her legs – yoga style + she looks like she's floating

The jottings are bald and rough. At the end of every few days, if not after every day's rehearsal, I write what I call "notes". Building on the jottings, they are extended descriptions, notes that not only clarify and tease out ‘what happened', but could form useful examples in a future analysis. Below is a fieldnote building on the above jotting:

One morning during the second week of rehearsals, performer, David Williams, is balancing effortlessly on a tall ladder attaching a thick rope to the rigging frame. Kym Vercoe, another performer, decides it is time "to have a play". With barely a pause, she slips into the harness, straps it tightly around her waist and backside, and clips it metres up onto the rope. She begins to twist and turn, testing the swing and arc of the rope. "I haven't used this harness for a while. It's got a great sound of breaking," she says. She flips around, using leg and abdomen muscles, pushing the limits of her movement. "It's nice having a little swing." She sits cross-legged, suspended metres from the floor, and it looks as if she is floating.

I have used this fieldnote in a recent article to explore the kinds of tacit, embodied knowledges artists bring with them to rehearsal (see Rossmanith 2008b). However, at the time of writing the jotting and then the note, I relied on a hunch to tell me that this observation was important and useful. It is what I tell students: trust that you will instinctively be drawn to dimensions of rehearsal practice you yourself will find interesting. The question later, then, is to ask: is what I found interesting the same thing as the practitioners found interesting? If not, why?

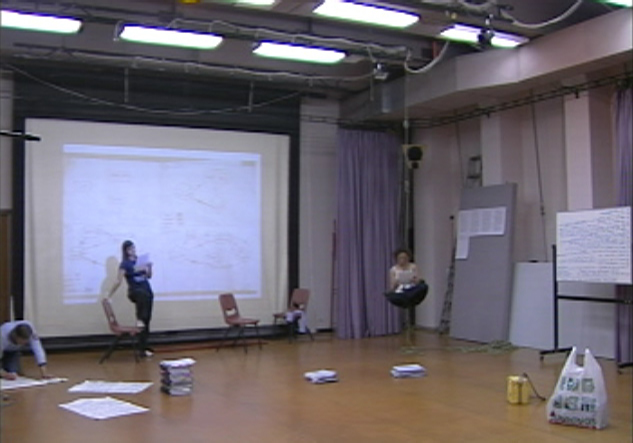

Figure 4, Kym Vercoe (right) sits cross-legged, suspended at the end of a rope. She reads the part of Dominic Hogan, an AWB employee, while fellow performer, Jane Phegan, as Commissioner Cole, questions her. This rehearsal process was recorded at the Department of Performance Studies, University of Sydney.<27>Whenever I write down a term, especially a performance term-– "actor", "blocking", "deliver", "scene run", etc –-I am always careful to note whether this is my term or the practitioners' term. For instance, after watching a rehearsal process for a piece of contemporary performance, a student observer instinctively referred to the practitioners as "actors". However, the practitioners did not understand themselves as actors, and never referred to themselves in this way-– except in moments of self-derision ("I'm being such an actor about this"). Instead they called themselves "performers" and "dramaturges". Once I pointed this out to the student, she was able to shape her final rehearsal analysis around the complex relationship the practitioners had towards ideas of "acting" and "performing" and "self-devising" theatre.

<28>This example points to a common pitfall inherent in conducting fieldwork in one's own social and cultural backyard: as researchers, we are too familiar with many terms, ideas and practices used by social agents, and can leap to our own ideas about what it going on rather than focussing on practitioners' understandings of what is happening. While an ethnographer in a strange, new place battles to gain familiarity, we must battle to gain distance. Our job as rehearsal analysts involves, in James Clifford's terms, looking obliquely at nearby collective cultural arrangements; "making the familiar strange" (1986: 2-3). And this goes for the construction of interview questions too. When interviewing practitioners – and often these take the form of informal interviews in coffee and lunch breaks-– don't be afraid to ask obvious questions, even questions you think you already know the answers to. During one rehearsal process, I noticed the heavy use of shorthand between director and actors-– "Sharpen that line", "Earn that beat", "Don't hug the furniture"-– and I suspected it had to do with shared training and performance background. But it was important I got the practitioners' own explanations. When I asked the director about this use of shorthand, he simply responded: "It's a NIDA thing". He was referring to the National Institute of Dramatic Art, arguably Australia's most prominent actor-training institution, and he was flagging the fact that most of the practitioners had attended the school. At the same time, however, his use of the term, "thing", points to what he saw as a set of discourses and practices that, together, was recognisably "NIDA" (see Rossmanith 2006: 81).

Coding and analysing field jottings and notes: the movement towards writing

<29>At the conclusion of rehearsals, most rehearsal observers attend opening night of the performance. But as the performers complete an often gruelling period of rehearsal, and settle into the rhythm of a performance run, this is when a rehearsal analyst's work really begins. It is when he or she "must shift gears and turn to the written record he has produced with an eye to transforming the collection of materials into writing that speaks to a wider, outside audience" (Emerson et al, 1995: 142).

<30>You might look at the stack of notebooks you have filled with jottings and notes, and wonder where to start. Emerson, Fretz and Shaw, in Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes (1995), suggest several strategies for dealing with the mountain of data you have created and collected. You must begin by reading through the field material, elaborating and refining earlier insights and hunches "by subjecting this broader collection of fieldnotes to close, intensive reflection and analysis" (1995: 142). And, according to the authors, you must begin coding your notes. They suggest that there are two coding phases: open coding, where the researcher "reads fieldnotes line-by-line to identify and formulate any and all ideas, themes or issues they suggest, no matter how varied and disparate" (1995: 143); and focussed coding, where the researcher "subjects fieldnotes to fine-grained, line-by-line analysis on the basis of topics that have been identified as of particular interest" (1995: 143). Importantly, they suggest: "To undertake an analytically motivated reading of one's fieldnotes requires the ethnographer to approach her notes as if they had been written by a stranger" (1995: 145), again pointing to the importance of distancing oneself from the set of knowledges that may, over time, have become familiar.

<31>It is also a time to ask questions of your notes. Emerson, Fretz and Shaw suggest these questions as useful in beginning to examine fieldnotes (1995: 146):

What are people doing? What are they trying to accomplish?

How, exactly, do they do this? What specific means and/or strategies do they use?

How do members talk about, characterize, and understand what is going on?

What assumptions are they making?

What do I see going on here? What did I learn from these notes?

Why did I include them?

In processing your notes, resist leaping to an overall idea. Let ideas swell from your jottings and notes rather than imposing a neat, overarching theme. Emerson, Fretz and Shaw suggest beginning to write "intergrating memos which elaborate ideas and begin to link or tie codes and bits of data together" (1995: 162). Robert Emerson also suggests working with key incidents as a way of grounding ethnographic analyses. "Key incidents suggest and direct analysis in ways that ultimately help to open up significant, often complex lines of conceptual development" (2004: 457). My fieldnote about Rebecca and the head shot would be an example of a key incident that helped shape the direction of my rehearsal analysis.

<32>In analysing your fieldnotes, and moving towards writing an account of the weeks you spent observing performance-making processes in action, remember that your task is to make sense of the way that others make sense of the work they do (Geertz 1983). In this way you are offering an (informed!) interpretation of the performance-making process (indeed, your interpretation began when you decided to document some things and disregard others). James Clifford foregrounds the writing aspect of the ethnographic enterprise, how it is processual, the "cultural poetics" of it (1986: 12). At the same time, writing fieldwork accounts involves "doing justice" (Jackson 1996: 43) to the weeks and weeks of creative practice. Below are questions to ask yourself, as well as organisational concepts to help you tease out your ideas.

<33>Your account will be grounded in "thick description". Clifford Geertz (1983) draws on Gilbert Ryle's idea of "thick description" to describe an ethnographer's finely observed details of social and cultural behaviour and exchanges, together with the locals' accompanying interpretation of such activity. In the case of performance-making processes, you must offer an account of how the practitioners understood/interpreted the work they were doing. Your account is not directed towards uncovering what the performance-making "meant"-– how performance elements encode "meaning"-– but, rather, to examine and explain how the performance-making process was understood as meaningful to practitioners [4]. (For instance, actor and scholar Paul Moore points out that structured, paid rehearsal is comparatively rare in the field of theatre in Australia, and as such is a "symbolically dominant form" [2006: 106].)

<34>One way to tease this out is to think about the practitioners' activity -– the doings -– and then how practitioners described those doings. That is, how did practitioners yoke particular sets of practices to particular discourses? Actors might sit at a table, read scripts aloud, and use their pens to highlight words, lines and stage directions. This is a practice, or set of practices. They might talk about this practice as "discovering the meaning of the play". Or they might describe it as "mucking around". As Phillip Zarrilli argues, "a practice is not a discourse, but implicit in any practice are one or more discourses [...] through which the experience of practice might be reflected upon and possibly explained" (1998: 5). You need to tease out what the practitioners did, and how they talked about what they did (for further examples, see Rossmanith 2006: 77). At the same time, were there sets of practices that weren't talked about at all? Did the practitioners engage in doings without verbally articulating those doings?

<35>You should also think about the different orders of discourse that were working through the process. Think about the discourses that operated within the practice as opposed to discourses operating about the practice. In my experience, there is often a distinction between the talk associated with a practice while practitioners engage in that practice, and then how that practice gets talked about to other people (Rossmanith 2008b). For practitioners, there is often a conscious discourse they use to talk about their work, and a less conscious discourse they use when they're caught up in the work (Rossmanith 2008b). For instance, practitioners might describe their work to the fieldworker as "collaborative", but a less conscious discourse of "sole authorship" might operate as the practitioners are engaged in the work. Similarly, practitioners might use phrases like "what a mess" and "what are we doing?" and "I'm confused" as they sift through notes. They then might turn to a fieldworker and say "We are making a scene". In this case, the less conscious discourse of "mess" and "confusion" works in parallel with the more conscious one of "making" performance.

<36>It is useful to think about the different knowledges that were articulated by practitioners. How did propositional knowledge operate? How did embodied knowledge operate? As Michael Jackson notes, "the knowledge whereby one lives is not necessarily identical with the knowledge whereby one explains life" (1996: 2). The practitioners might have made verbal declarations about their work and the world (propositional knowledge); they might also strap on a harness and twist and turn down giant ropes. The latter is a form of embodied knowledge, where knowledge is articulated physically rather than verbally. It is a knowledge "urgently of and for the world rather than something about the world" (Jackson 1996: 37). Actors' work in rehearsals is often just that: a physical manifestation of years of professional experience involving very practical knowledge (see Maxwell 2001b). And often this knowledge is not consciously verbally articulated.

<37>Your job is, in part, to be clear about whose terms you are using. Are they your terms or the practitioners' terms? For example, if you use the term ‘scene' to describe a section of the production, is it their term or yours? Did they talk about the show in terms of "scenes", or in less formal terms, such as "that section" and "this bit"? For the most part, try to use the terms the practitioners used – being sure to flag that they used them. Sometimes, you will decide to use your own term, especially when the practitioners don't verbally articulate, or label, their doings themselves. If you do label a set of practices in a particular way, be sure to indicate that it is your term.

<38>Another way to think about concepts and terminology is in terms of "experience-near" concepts and "experience-distant" concepts [5]. Geertz (1976: 223) borrows Heinz Kohut's distinction in order to think about the lay, immediate terms cultural participants use to talk about their experience of life, and the equivalent abstract terms often used by academics and other theorists. As Geertz points out, "the matter is one of degree, not polar opposition" (1976: 223). He uses the example of "love" (experience-near) and the equivalent term that might be used by a psychoanalyst, "object cathexis" (experience-distant). In your account, you should use experience-near and experience-distant concepts, thereby grounding your work in practitioners' terminology (and associated experiences) as well as your own analysis. For instance, a practitioner might describe himself: "I may have a rough exterior but I only reveal the softer layers of myself when I trust someone". This is an experience-near concept of himself as a person. You might quote him and then talk about this in terms of a particular "topography of the self" (Appadurai 1990: 92)-– an experience-distant concept. A good ethnographer is able to move effortlessly between this terminology.

<39>It might be relevant for you to think of yourself in terms of the insider-outsider continuum (for a discussion, see Rossmanith 2004: 224-8). What happens when you do research in your own social and cultural backyard? What happens when you've been a part of the field – theatre or opera or dance – that you are researching? You might call yourself a "semi-insider" (Lewis 1992), or an "outsider-insider" (Zarrilli 1998: 11). To what extent are you "inside" the group you're studying? How are you outside it? If you are familiar with the meaning of terminology-– for example, "beats", "blocking"-– be sure to bracket out what you think you know, and concentrate on teasing out how the practitioners understood those terms. Be sure to sustain a "presence of foreignness" (Tomlinson 1993: 23).

<40>Ethnographic fieldwork is often described as "participant observation". You are in the room with the practitioners, breathing the same air, listening to the same music, drinking the same coffee. You may even participate in some of the activities. Warm-ups? Dramaturgical assistance? Spending shared time together, you are not only observing; fieldwork privileges the body – your body – as a site of knowing (Conquergood 1991: 180). In doing warm-ups with practitioners, you move as they move; you get to feel what it is for bodies to move that way. This is a form of knowledge. While rehearsal observers generally won't become involved in the actual production, their shared space and time with the performers-– including, occasionally warm-up practices-– is embodied and performative.

<41>As a fieldworker, you may feel it appropriate to tease out the biases you brought with you to the fieldwork. Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu refers to this as the fieldworker's reflexivity. Ian Maxwell summarises Bourdieu's thinking on this. "For Bourdieu, reflexivity is not achieved through engaging in reflections on fieldwork, nor through the use of the first person, but by ‘subjecting the position of the observer to the same critical analysis as that of the constructed object at hand'" (Maxwell 2001a: 47). For instance, Bourdieu argues for a "need to systematically address three biases that blur the analyst's gaze", writes Maxwell (2001a: 48). The first concerns the social origins and coordinates (class, gender, ethnicity, etc) of the individual researcher. The second concerns the fieldworker's position in the academic field. The third "is that ‘intellectualist bias' which ‘entices us to construe the world as a spectacle, as a set of significations to be interpreted rather than as specific problems to be solved practically'" (Maxwell 2001a: 48).

<42>At the end of this, as you have asked yourself these questions-– asked your material these questions-– it is time to think about the big idea you may wish to concentrate on. Ask yourself: How did I reach this idea? How does it seek to explain the ways in which the practitioners made sense of what it is they thought they were doing? Why is this a useful way to think about the months of rehearsal? What sub-ideas will you use to investigate/ map out this broader idea? In answering these questions, you will develop an essay plan for your rehearsal analysis.

Rehearsal Analyses

<43>By means of concluding this article, I wish to set out some of the conceptual ideas underpinning several rehearsal analyses. In my own work, for instance, I have been interested in the ways in which the day-to-day micropractices of rehearsal are intimately connected to broader macro-institutional contexts. For example, I have explored how moments in rehearsal that "felt right" for practitioners, where as a group they had a sense-– in the literal sense of "sense"-– that they had "got it right", were closely caught up in ideas about what constituted being a "professional" practitioner with appropriate theatre training, producing high quality work (see Rossmanith 2006).

<44>In another rehearsal analysis, I considered the ways in which practitioners speak differently about their work depending on whether they are caught up in that work. For example, in one rehearsal process, the practitioners did not explicitly refer to the expert physical training many of them brought to rehearsals, and instead talked about their practice as "having a play" and "mucking around". It was not until well after rehearsals had finished that the performers reflected on their work differently: "Each individual artist bring[s] their own history of aesthetic" (Boukabou 2007: 32), a performer told a journalist (see Rossmanith 2008b).

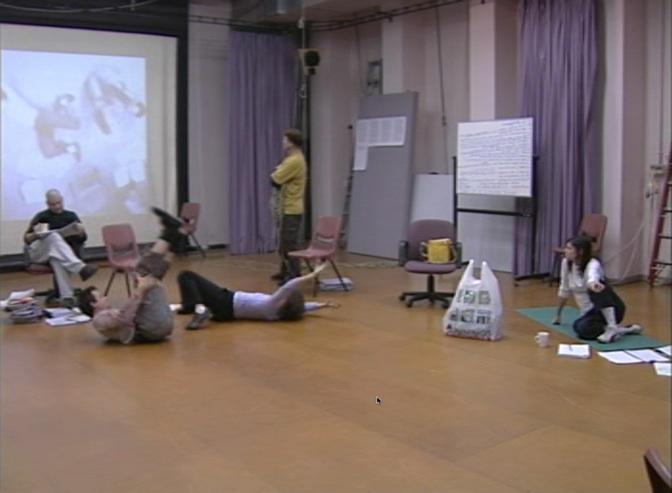

Figure 5, version 1.0 practitioners–-David Williams, Stephen Klinder, Kym Vercoe, Chris Ryan, and Jane Phegan-– tell us they are "mucking around", when their work involves reading 8,500 pages of inquiry transcript and drawing on their training in physical performance (among other things) to find ways in which to shape and perform sections of it.

<45>I have also worked with students as they develop their own rehearsal analyses. One student wrote of the (very visceral) ways in which dancers learn and are taught choreography; and another explored the constant to-and and fro-ing of a self-devised performance group as they simultaneously attempted to keep their creative decisions "open" and "locked in". And, as a way to think about the rehearsal process of the Sydney performer, Nigel Kellaway, a student wrote of the dual discourses Kellaway used to talk about the devising of performance. Kellaway would talk of "collaboration" with other performers, but at the same time would continually articulate how the vision of the show was "all in [his] head". "It's in my dreams", he would tell the student. The rehearsal analysis focussed on the tension between collaborative approaches to performance and the practice and discourse of sole authorship.

Figure 6, Nigel Kellaway in full flight in his show, The Terror of Tosca, 1998.

<46>Other scholars have reflected on rehearsal in different ways. McAuley (1999) has focussed on the use of space in rehearsal; Laura Ginters (2006) has written about "magic moments" in rehearsal; Terry Threadgold (1995) has looked at gender politics and postmodern theories of authorship; Kerrie Schaefer (1999) has studied the practice of "poaching" in postmodern performance-making; C. M. Potts (1995) has analysed the use of jokes and anecdotes in rehearsal as a way of circulating craft knowledge; and Ian Maxwell (2001b) has considered how a crisis during rehearsals unexpectedly foregrounded the sociological dimension of such artistic activity.

<47>Finally, whatever the particular richness of the performance-making process you may study, and whatever dimension your analysis takes, hopefully you will begin to grapple with, what David Selbourne laments is, "the tangled process of rehearsals" (1985: 221).

References

Appadurai, Arjun. 1990. "Topographies of the Self: Praise and Emotion in Hindu India". In Language and the Politics of Emotion, eds. L.Abu-Lughod and C.Lutz. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. pp. 92-112.

Born, Georgina. 1995. Rationalizing Culture. London and California: University of California Press.

Boukabou, Ruby. 2007. "Deeply Offensive and Utterly Untrue: Chris Ryan with version 1.0 at Carriageworks". In Brag, issue 224, 20 August, p.32.

Callow, Simon. 1984. Being an Actor. London: Penguin Books.

Carlson, Marvin. 1989. Places of Performance: The semiotics of theatre architecture. Ithaca and Londond: Cornwell University Press.

Casey, Edward. 2001. "Between Geography and Philosophy: What does it mean to be in the place-world?". Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 91 (4): 683-693

Clifford, James. 1986. "Introduction: Partial Truths". In Writing Culture--The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, eds J. Clifford and G. Marcus. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cole, Susan Letzler. 1992. Directors in Rehearsal: a Hidden World. London: Routledge.

----.2001. Playwrights in Rehearsal: The Seduction of Company. London and New York: Routledge.

Conquergood, Dwight. 1991. "Rethinking Ethnography: Towards a Critical Cultural Politics". Communication Monographs 58. pp179-194.

Constantinidis, Stratos E. 1988. "Rehearsal as a Subsystem: Transactional Analysis and Role Research". New Theatre Quarterly 4(13). pp 64-76.

Cox, Brian. 1992. The Lear Diaries: The Story of the Royal National Theatre's productions of Richard III and King Lear. London: Methuen.

Emerson, Robert, Rachel Fretz, and Linda Shaw. 1995. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

----.2004. "Working with Key Incidents". In Qualitative Research Practice, eds. Seale, Gobo, Gubrium and Silverman. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: Sage Publications, pp 457-472.

Feld, Steven. 1994. "Aesthetics as Iconicity of Style (Uptown Title); Or, (Downtown Title) ‘Lift-Up-Over-Sounding': Getting into the Kaluli Groove". In Music Grooves, eds. Charles Keil and Steven Feld, pp 109-150. London and Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Filmer, Andrew. 2006. Backstage Space: The place of the performer. PhD dissertation. Department of Performance Studies, University of Sydney.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

----.1976. "‘From the Native's Point of View': On the Nature of Anthropological Understanding". In Meaning in Anthropology, eds. Keith H. Basso and Henry A. Selby, 221-237. Albuquerque: University of Mexico Press.

----.1983. Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology. New York: Basic Books.

Ginters, Laura. 2006. "‘And there we may rehearse most obscenely and courageously': Pushing limits in rehearsal". About Performance, No. 6. pp. 55-74.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

----. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hastrup, Kirsten. 1992. "Writing Ethnography: the State of the Art", in Okely and Calloway, eds, Anthropology and Autobiography. London: Routledge, pp 116-33.

Hiley, Jim. 1981. Theatre at Work: The Story of the National Theatre's Introduction of Brecht's Galileo. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Hite, Roger W., Jackie Czerepinski, and Dean Anderson. 1973. "Transactional Analysis: A New Perspective for the Theatre". Empirical Research in the Theatre, 1-17.

Jackson, Michael.1996 (ed).Things as They Are: New Directions in Phenomenological Anthropology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Leader, Kate. 2007. "Bound and Gagged: The Role of Performance in the Adversarial Criminal Jury Trial". Philament, Volume 11.

Lewis, J. Lowell. 1992. Ring of Liberation: Deceptive Discourse in Brazilian Capoeira. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Mackintosh, Iain. 1993. Architecture, Actor and Audience. London and New York: Routledge.

Maxwell, Ian. 2001a. "Learning In/Through Crisis". Australasian Drama Studies, No.39. pp 43-57.

----.2001b. "Acting and the Limits of Professional Craft Knowledge". In Practice, Knowledge and Expertise in the Health Sciences, eds. J. Higgs & A. Titchen, 102-107. Australia: Butterworth Heinemann.

----.2003. Phat Beats, Dope Rhymes: Hip Hop Down Under Comin' Upper. Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.

McAuley, Gay.1998. "Towards an Ethnography of Rehearsal". New Theatre Quarterly 38: 183-94.

----.1999. Space in Performance: Making Meaning in the Theatre . USA: University of Michigan.

----.2006. "Introduction". About Performance, No. 6. pp. 7-13.

Miller, Keith A., and Clarence W. Bahs. 1974. "Director Expectancy and Actor Effectiveness". Empirical Research in the Theatre, 60-74.

Moore, Paul. 2006. "Rehearsal and the Actor: Practicalities, Ideals and Compromise". About Performance No. 6. pp 93-108.

Ness, Sally Ann. 2007. "Choreographies of Tourism in Yosemite Valley: Rethinking ‘place' in terms of motility". Performance Research, 12 (2). pp 79-84.

Okely, Judith. 1996. Own or Other Culture. London: Routledge.

Overington, Caroline. 2007. Kickback: Inside the Australian Wheat Board scandal. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Porter, Robert E. 1975. "Analyzing Rehearsal Interaction". Empirical Research in the Theatre, V. pp. 1-31.

Potts, C. M. 1995. What Empty Space?: Text and Space in the Australian Mainstream Rehearsal Process. M.Phil thesis, University of Sydney.

Powers, William, David Jorns, and Robert Glenn. 1980. "The Effects of Cognitive Complexity on Characterization Depth and Performance". Empirical Research in Theatre, VI.

Rosenthal, R. and K. L. Fode. 1963. "The Effect of Experimenter Bias on the Performance of the Albino Rat". Behavioral Science, Volume 8. pp. 183-189.

Rossmanith, Kate. 2004. Making Theatre-Making: Rehearsal Practice and Cultural Production. PhD dissertation. Department of Performance Studies, University of Sydney.

----.2006. "Feeling the Right Impulse: ‘Professionalism' and the Affective Dimension of Rehearsal Practice". About Performance, No. 6. pp. 75-92.

----2008a. "We Are Cells: Bioart, Semi-livings and Visceral Threat". Performance Paradigm (4). pp 1-18

----2008b. "Traditions and Training in Rehearsal Practice". Australasian Drama Studies, Volume 53, pp. 141-152.

Schaefer, Kerrie.1999. The Politics of Poaching in Postmodern Performance: A Case Study of the Sydney Front's Don Juan in Rehearsal and Performance. PhD dissertation. Department of Performance Studies, University of Sydney.

Schechner, Richard. 2002. Performance Studies: An Introduction. London, New York: Routledge.

Selbourne, David. 1982. A Making of A Midsummer Night's Dream. London: Methuen.

Sher, Anthony. 1985. Year of the King. London: Chatto and Windus.

Stafford-Clark, Max. 1989. Letters to George: The Account of a Rehearsal. London: Nick Hern Books, Walker Books Ltd.

Threadgold, Terry. 1995. "Postmodernism and the Politics of Culture: Chekhov's Three Sisters in Rehearsal and Performance". Southern Review 28(2). pp 172-182.

Tomlinson, Gary. 1993. Music in Renaissance Magic: Toward a Historiography of Others. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Trauth, Suzanne. 1980. "Effects of Director's System of Communication on Actor Inventiveness and Rehearsal Atmosphere". Empirical Research in Theatre, VI.

Zarrilli, Phillip. 1998. When the Body Becomes All Eyes: Paradigms, Discourses and Practices of Power in Kalarippayattu, a South Indian Martial Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Notes

[1] My deep gratitude to Gay McAuley, Laura Ginters, Paul Dwyer, Russell Emerson, Ian Maxwell, Tim Fitzpatrick and Lowell Lewis from the University of Sydney, all of whom have an interest in the intersection between rehearsal studies and ethnography, and whose writing and teaching continually inspire me. My thanks also to all the practitioners whose work I have documented over the past decade – particularly version 1.0 and Nigel Kellaway for allowing me to use these images. [^]

[2] For an overview of the discipline of Performance Studies, see Richard Schechner (2002). See also Iain Mackintosh's (1993) work on architecture, actors and audiences; Marvin Carlson's (1989) study of the semiotics of theatre architecture; Kate Leader's (2007) research on the role of performance in courtroom trials; my own thinking (Rossmanith 2008a) on the use of human tissue in "bioart" installations and the effects this produces in spectators; and Sally Ann Ness's work on "tourist choreographies" (2007). [^]

[3] For a discussion about the emerging field of rehearsal studies, see McAuley 2006. [^]

[4] See Geertz (1983: 118). Ian Maxwell (2003: 180-88) makes a similar point in his work on the Hip Hop community in Sydney.[^]

[5] Steven Feld (1994) uses the comparable ideas of ‘uptown' and ‘downtown' to distinguish between intellectual or abstract concepts and immediate, grounded terminology. [^]

Return to Top»