Reconstruction 9.1 (2009)

Return to Contents>>

Reading Between the Lines: Understanding Assistants in Fieldwork / Rina Sherman

Abstract: In this presentation I will look at the various levels of interaction between the three agents, the researcher, the assistant and members of the community within which research is being conducted within the context of my fieldwork amongst the Ovahimba people over a period of seven years. The potential interaction between these three agents are manifold and can be questioned in a number of ways, of which: What the researcher wants, what the assistant thinks the researcher wants, what the assistant wants in terms of his or her respective relationships with the researcher and members of the community, what members of the community want from the assistant and also through the assistant from the researcher. I will also examine how research methods were adapted to the level of skills of assistants and how in turn the assistants' skills influenced research methods, as well as why finally, I decided to work without assistants and outsource the skills I did not have, e.g. Word by word translation from Otjiherero to English. Various case studies will be referred to throughout, most notably the dramatic case of Tjomihano, the only assistant that was a member of the local community.

"You are One the Way"

<1> When I returned to Paris after three months in the field for a first short visit, I rushed to a meeting with Jean Rouch with a set of questions I expected him to answer and being sure that he would provide sure solutions to the initial problems encountered in the field. Most of my questions were related to pressure from members of the community to give them things: money, medication, alcohol, tobacco, transportation and so on. Rouch listened and said none. I showed him some photographs. He asked when there would be rushes to see. As he stood up to leave, he said: "These are problems everybody experiences. We tried to make sure that people had work. Damouré has his clinic, Lam was paid to be a driver and Tallou has his livestock. His eyes shone, he shook my hand and pushed me off, saying: "You are on the way." I heard: "You are on your own". Rouch's attitude reflected a school of thought in which finding one's own solutions to problems were one of the best ways of learning.

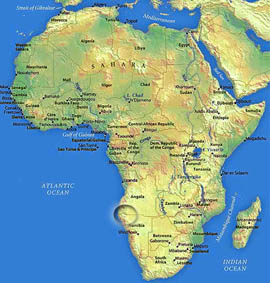

Map of the African continent, showing Namibia and Angola, home to the Otjiherero language-speaking groups, situated in the north-western part of Southern Africa.

Introduction

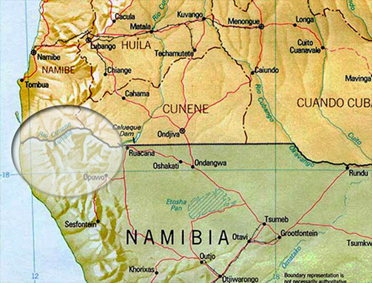

<2> In this multimedia presentation, I will examine the development of relationships between informants, members of the community and myself during my seven years of fieldwork for the project The Ovahimba Years [1]. I will show how relationships of informants to different members of the community, as well as to myself, influenced and contributed to my fieldwork and the general evolution of the project over a period of seven years. During fieldwork for this project, I lived for seven years with the extended Ovahimba family of the Headman of Etanga, a hamlet situated in the North-western Kunene Region of Namibia. I spent a part of the last year of my sojourn in the field with the Ovahimba and related peoples that live in the South-western Cunene and Namibe provinces of Angola [2].

<3> The relationship between the researcher, informant(s) and members of the community within which an ethnographic study constitutes a variable dynamic requiring constant adaptation. As relationships evolve in time and researchers acquire a working knowledge of the people they work with, this triangular interaction becomes increasingly complex and may at times overshadow the objectives of the study as initially stated. As Clifford Geertz states in his essay Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture [3]:

What the ethnographer is in fact faced with... is a multiplicity of complex structures, many of them superimposed upon or knotted into one another... which he must contrive somehow first to grasp then to render... Doing ethnography is like trying to read (in the sense of ‘construct a reading of') a manuscript.

In the field, the ethnographer is in contact with people who present knowledge of their culture as the truth. Belief in the truth of the body of knowledge of a given cultural identity is a common requirement in mankind. Such an interpretation of reality provides a set of fixed references within the culture and as such a constant through which to read the world at large. My objective in the project "The Ovahimba Years" is to represent the individual and collective experiences of how this knowledge is acquired--both from within Ovahimba society and from the outside world--,transmitted and applied in the flow of interaction between the living and their corresponding ancestral--and animal spirits.

Map of the Kunene North Region of the north-west of Namibia, and the Cunene and Namibe provinces of the south-west of Angola, the cross-border region where the Otjiherero language-speaking groups live.<4> The Ovahimba Years is a long-term multi disciplinary study of the cultural heritage of the Ovahimba and related peoples of the Otjiherero language-speaking group of North-western Namibia and South-western Angola. The objective of this study is to create a body of work that will represent through various media (film, video, photography, drawings, sound recordings and text data) the everyday- and ritual life of the Ovahimba and related peoples in order to bring to life the vast complex of interrelations and interactions between the living and the spirits of the dead, both human and animal. The different media used to record data throughout fieldwork in this ethnographic study are intended to form a whole, within which one type of representation will refer the observer to another. For example, one of the films of the "The Ovahimba Years" film collection may refer the viewer to a text, another film, a drawing, or a photograph. The different media used to record data in the field are intended to constitute a whole in which the various elements contribute to an emerging representation of the ancestral culture of the Ovahimba.

<5> The proposition to use different disciplines and multiple media as expressed in different works (films, books, exhibitions, etc.) to arrive at a global ethnographic description, raises the question of the place of writing, the discipline by predilection of classical anthropology, in an ethnographic study. Jay Ruby, in his critical review of the last 20 years of visual anthropology indicates that tenure or promotion based on principally on film production is rare in the US and that in discussions on multi-vocal and reflexive ethnography amongst contributors to Writing Culture (Marcus and Clifford 1986) showed no evidence of awareness of Jean Rouch's ideas and work undertaken since the early 1960's (see Rouch and Morin's Chronicle of a Summer, 1962)[4]. Ruby hence suggests that theoretical discourse continued to exclude visual anthropology from its discussion whilst filmmakers such as Rouch had been experimenting with ethnographic forms of filmmaking for twenty years. Later in the same article, Ruby quotes Pieter Biella from the latter's article, Beyond Ethnographic Film: Hypermedia and Scholarship [5]:

Both films and printed materials have severe limitations that can only be overcome with a multimedia format combining the printed word, photographs and motion pictures (film and video) into an integrated whole.

Whilst my study of the Ovahimba is not presented as an interactive hypermedia presentation, it does work as a whole in the sense that there is continuous cross-referencing and hence interactivity between the various elements (film, photographs, text, etc.) of the collection.

<6> For an ethnographer working in a foreign culture, at least initial contact with members of the studied community will be sought through the assistance of an interpreter/informant. The personality and level of skills of the informant and his disposition toward individual members of the society and the group as a whole will inform the ethnographer's choices in the field. The informant's sensibility may influence the choices of the ethnographer in terms of what is included and excluded and how it is included or excluded. In other words, he contributes to the point of view the ethnographer will establish in his study. In Mediations in the Global Ecumene[6], Ulf Hannerz concludes that the various aspects of ethnography, such as explanation, interpretation, could be referred to as "the work of translation". Whilst the end-result of "The Ovahimba Years" study is not limited to text, but expands the translation process to different forms of audio and visual media, the discourse is constituted throughout by translation in various forms: interpretation of the interpreter of his own or a closely related culture, interpretation by members of the society of their own culture, and the interpretation of the researcher of information received, recorded and experienced.

<7> Exiled from South Africa in 1984, with the change of political climate in the early nineties, I started returning to Southern Africa for different research studies, of which an examination of contemporary South African culture through film archival holdings. In the National Archives of Namibia, I viewed a collection of John Marshall's films of the San [7] and came upon a collection of early photographs depicting the Ovahimba/Ovaherero. An initial survey of literature on the Ovahimba and other Otjiherero language-speaking groups showed early interest in these cultural groups by missionaries, such as Father Carlos Estermann, German and South African administrators, of which Hahn, Vedder and Malan, followed by Cardoso's and Gibson's studies and films of the 1950's, and as from the 1980's, Bollig, Crandall, Von Wolputte and Wärlöf [8]. These predominantly text-based studies cover a range of issues such as ethnicity, ethnic distribution, material culture, pastoral economic organisation, animal classification, dual descent and symbolic classification systems, providing focussed studies of the Ovahimba, with mention and peripheral treatment of the other Otjiherero language-speaking groups. Scope existed for an extensive long-term multimedia study with in situ observation of Ovahimba everyday- and ceremonial life, of the dense and complex imaginary universe of the Ovahimba, in which they move seamlessly from sacred to material expressions from one moment of life to the next in the here and now.

<8> The Ovahimba are a pastoral people numbering according to unofficial and approximate statistics about 16,000 people in Namibia and about a third more living north of the Kunene River border in Angola. They occupy a vast and rugged expanse of land comprising some 20,0000 km2 south of the Kunene River in Namibia, known as Kaokoveld or Kaokoland, and a similar tract of land of the south-western Cunene province, including a part of the Iona National Park in the Namibe province of Angola. The country occupied by the Ovahimba and related peoples, is mountainous and jiggered, with continuous chains of hills, mountains and valleys, with peaks reaching an elevation of over 1500m. The valley floors are covered with arid savannah and savannah woodlands, most of which Mopani or Omutati woodlands, with an average sporadic rainfall ranging from 100mm to 300mm [9]. The Ovahimba form a part of the Otjiherero language-speaking Bantu groups of Namibia and Angola. These include the Ovaherero and a number of smaller groups such as the Ovadhimba, Ovahakahona, Ovakuvale, Ovakwanyoka, Ovacaroca, and sub-groups such as the Ovatjimba, Ovatjimba-tjimba, Ovatwa and the Ovagambwe [10].

<9> The Ovahimba are cattle-farmers observing a marked distinction between sacred and secular animals. Ovahimba society has a dual descent rule, maternal and paternal, the two lines respectively determining social, material, and symbolic identity within the extended family. Matrilineal descent not only determines the heritage of most livestock and other non-consecrated wealth but also far-reaching ties with related peoples with whom the Ovahimba share common matrilineal clans. Patrilineal descent is organised around the attachment to a specific sacred altar or Okuruwo through which contact is maintained with related ancestors. It determines exclusion and inclusion in the patrilineal segment of the family through which individuals gain access to the sacred practices and cattle and other ritual objects and to a predetermined position within the family ranking. The Ovahimba and their related pastoral peoples practice transhumance, herding livestock according to a dual season year. During the dry season, some members of the family drive livestock into the mountain winter pastures where they establish cattle posts until the rain returns and replenishes the grasslands in the valleys where the principal homesteads are located. During the rainy season, maize and vegetables, such as pumpkins and beans are grown on the flood plains of the rivers.

The Headman of Etanga seated in the ring of flat stones forming the central area of the sacred altar, surrounded by councillors and elders during the funeral rites of a child that died under a spell intended to capture its soul. Infants' souls are believed to make good herders and enrich the owner.

<10> My choice of location for the seven years of my fieldwork is a result of historical evolution and of the current situation of the Ovahimba in the Kunene Region of Namibia. Prior to the arrival of the Portuguese, German and after 1918 the South African administrations in what is known today as Angola and Namibia, the pastoral peoples of this region were organised according to a close relationship between different groups and clans within the groups and the land they occupied at different pre-colonial times [11].

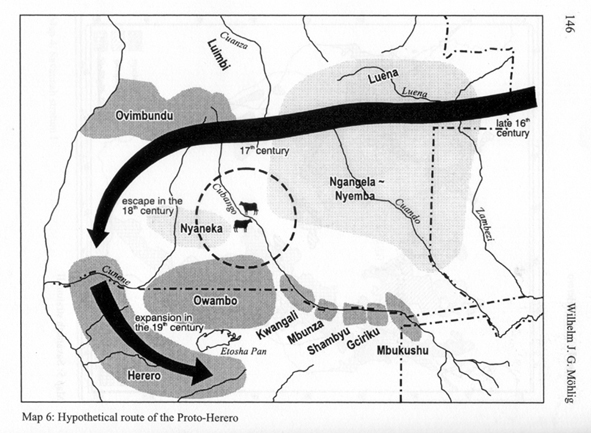

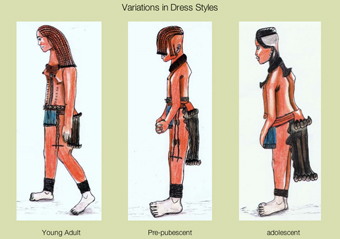

A map summarizing a hypothetical history of the Otjiherero language-speaking peoples, as set out by Wilhelm J. G. Möhlig in "The Language History of Herero as a Source of Ethno-historical Interpretations" in People, Cattle and Land.

Their internal organisation was typically not based on social stratification, and conflict resolution was based on consensus rather than on institutional force. With the arrival of colonial powers, the need arose to implement some form of administration into these societies living mostly in the remotest areas of the occupied territories. The early missionaries, upon their arrival in a homestead, would identify the oldest man and use his status and wisdom as a metaphor through which to explain the Holy Trinity of the Christian religion. In this way, the Supreme Being or Ndjambi become known as Mukuru (omukuru) from the word Omukururumenu or "old father". In a similar way, the first administrators that were sent into these remote regions identified the Omuhona (Ovahona in the plural) or rich man, that is, the man who controlled the largest herds of livestock and area of grazing fields, as the leader in the community. He subsequently became known as Oforomana from the Afrikaans word "voorman" or "foreman", in Namibia, and "Soba" in Angola. The administrations compensated these designated leaders in a variety of ways in exchange for accepting some responsibility within the community and towards central government. Today, there is a synergy of different methods of government--between former acephalous and modern pyramidal - but the fusion of older systems with emerging government agencies at times cause confusion over accountability for executing and acting on some community issues[[12].

<11> Upon my arrival in Namibia, I was consistently referred to the local Headmen for contact within Ovahimba society. Initially, I resisted the idea of a Headman being the only point of entry into a given community. I soon realised that it was essential to acquire authorisation from a local Headman for the implementation of my project; I was referred to them by government and NGO agents, as well as by members of the community themselves. I eventually decided to stay at the homestead of the Headman of Etanga since he seemed to place the least pressure on me in terms of solving his own problems during our first encounter. In retrospect, I could not have done otherwise but stay in his homestead, since all kinds of permissions and decisions that I needed, from cutting trees to accessing water resources had to be obtained from him. However, I did witness cases where his own children would counter his decisions, for example, once when I had cut trees to construct a hut with the permission of the supposed owner of the land, he indicated to me that it was illegal without his permission; he was responsible for the land of the entire region and he was answerable to the Department of Nature Conservation for any cutting of trees. At this point, Kakaendona, his youngest daughter said: "Father, you accepted this child as your own in our house. If she needs trees to build her hut, she has to cut trees." A long silence followed and no more was said regarding the pile of trees lying ready to be built into a hut.

The Headman exchanging gazes with his daughter Kakaendona (standing), as he watches her, Kapandi, her eldest sister, (seated) and Kozondana, her nephew bringing finishing touches to the hut in question.

One day, toward the end of my stay, the Headman of Etanga, said to me in relation to a missionary who set up camp outside a nearby homestead and had everything he owned stolen: "You are different, you did the right thing coming to stay with us in our homestead, you are protected by me." During my seven year stay in his homestead, I was neither exempt from theft nor did I ever feel the need for protection, but in retrospect I have realised that the headman and the members of his family, who over time adopted me as one of their own, did in fact on many occasions do just that, protect me from jealousy, pressing demands and also theft in some cases. Before entering the field, one aspires to or worse pretends to have a global view of the local situation. However, soon, one becomes entangled in micro situations with assistants and members of the community that lead to localised decisions often based on a single individual's opinion or advice. In such situations, the initial global view no longer forms a predominant part of the decision making process.

Project assistants, Ovahimba friends and Rina Sherman after pitching the film-editing tent. Front centre to left: Vekumba Tjambiru, Musisi Humu, James the Builder; Back right to left: Rina Sherman and Uauhareka Tjambiru.

Into the Field

<12> During my seven years of fieldwork working on the project "The Ovahimba Years", a number of assistants accompanied me into the field, stayed at the camp established at the Headman of Etanga's homestead and were employed for a variety of responsibilities and for various periods of time. Some were literate, some not, some spoke English and/or Afrikaans, some only Otjiherero; job descriptions were defined according to each individual's particular capacities. Tasks assistants were contracted to do, ranged from interpreting, transcribing, translating, camp management, and livestock herding to participating in everyday activities, rituals and ceremonies that I filmed and photographed. Assistants employed to translate were expected to interpret my encounters with members of the Ovahimba community and were gradually taught computer and video skills in order to transcribe field recordings directly into the computer [13].

Tjomihano helping Magic to transcribe and translate Ovahimba praises.<13> In my search for assistants, I soon realised that the kind of skills I required did not really exist. Some candidates had previously worked with anthropologists as interpreters; others had no specific qualification and were simply looking for employment. My methods differ from those of colleagues who preceded me in the field in that their work is predominantly text-focussed. My foremost form of data collection is audiovisual through film, video and sound recordings, and visual through photography and drawings, which requires flexible presence in time and space. Ethnographic reporting, be it in text, still image or audiovisual, reflects the point of view of the author or ethnographer, who ultimately decides what is included or not. Furthermore, in my case, my performance art and artistic backgrounds lead me to make allowance for a measure of improvisation, for the people I study, my assistants and myself. As Jean Rouch summarised in Filming reality, and the documentary vision of the imaginary [14]:

As a filmmaker and ethnographer, I see virtually no boundary between documentary film and fiction film. As the art of the double, cinema is inherently a transition from the world of the real to the world of the imagination, and ethnography, as the science of other peoples' thought systems, is a permanent crossing over from one conceptual universe to another, a form of acrobatic gymnastics where losing one's footing is the least of the risks one runs.Incorporating elements of fiction and improvisation as possible and plausible dimensions of reality, as I do, it was more interesting for me to work with assistants with no prior experience, and hence avoid unfortunate comparisons with the working methods and requirements of their previous experiences as assistants. With fiction and improvisation I mean the possibility of imagining elements of reality - not to make them up -, to reveal such dimensions as plausible elements within their context. I followed the same method with the Ovahimba, in the sense that I would follow up on suggestions they would make in their efforts to understand what I was doing and what I required from them. I would follow avenues as opportunities arose and assistants' job descriptions where consequently defined according to individual capacities and redefined according to opportunities that arose. One example in case is an assistant whose job definition was revised to assign him to make drawings of Ovahimba everyday and ritual activities that would complement the subject matter that I was filming or photographing.

A sample of one of Musisi's drawing assignments in relation to my study of Ovahimba dress.

From ensuing discussions of the drawings, he would volunteer information that he may not otherwise have thought of communicating. In the long run, especially in the case of fieldwork extended over many years, the ethnographer, his assistants as well as members of the community are transformed by what eventually becomes a common experience. The researcher not only moulds and transforms his initial objectives to the reality in the field, but he himself is also transformed as he absorbs the way of thinking of the people he is studying. The assistant, to a greater or lesser degree, becomes drawn into the research process, trying to incorporate the needs of the researcher and those of the community, as well as looking after his own needs in relation to both. The members of the studied community incorporates the presence of a semi-permanent visitor, with different ways of thinking, who focuses on aspects of their culture of which they are not necessarily aware. But as the triangular relationship between the ethnographer, informant and community members evolve, each starts creating his own discourse in accordance with how he sees the other's needs in relation to his own. As Jean Rouch states in Ciné-Ethnography [15]:

All I can say today is that in the field, the simple observer modifies himself. When he is working, he is no longer the one who greeted the old men at the edge of the village. To take up the Vertovian terminology, he is "ciné-ethno-watching," he "ciné-ethno-observes," he "ciné-ethno-thinks." Those who confront him modify themselves similarly, once they have placed their confidence in this strange habitual visitor. They "ethno-show" and "ethno-talk," and at best, they "ethno-think," or better yet, they have "ethno-rituals." It is this permanent "ciné-dialogue" that seems to me one of the interesting angles of current ethnographic progress: knowledge is no longer a stolen secret, later to be consumed in the Western temples of knowledge. It is the result of an endless quest where ethnographer and ethnographees meet on a path that some of us are already calling "shared anthropology".<14> Finding an assistant for an ethnographic study often turns out to be an arduous task. The nature of what it entails to be a field research assistant can differ so much from one researcher, project or field to another, that defining the task is a challenge in its own right. One decisive factor in defining the job profile of a field assistant depends on whether the researcher speaks the language of the people with which he or she will work or not. If not, the assistant needs to be proficient in both the source and target languages and a reliable translator. In both cases, the assistant needs to have an in-depth understanding of the source culture. As an intermediary between the researcher and the community, he has to deal with constantly intermingling realities and partial solutions, as members of the community parts with their visions and opinions as they emerge in successive situations. To work as an assistant with an ethnographic researcher in the field may be neither the dream nor the aspiration of many a young person that ends up doing just that, simply because there is a demand and because other options of employment are non-existent. This seems to be the case of many of the young people I interviewed and the case of almost all of those that I finally employed as assistants. Over the first three-year period of my sojourn in the field, I employed some seven assistants for periods ranging from two months to three years. Some were from urban backgrounds and did not adapt to the harsh living and working conditions in the field or could not stand the isolated lifestyle. Others, had vested interests in the local community or were part of the community and were content to have employment in a parallel situation and hence benefit from earning cash and be able to participate in community life.

<15> In my case, having made several linguistic/cultural shifts prior to my fieldwork [16], I knew that learning the language of the Ovahimba was vital to gaining understanding of their thought system. But I also knew that one can learn about the way people think even if one does not understand everything they say; by being attentive to gesture, by listening to pitch and tone, and, to use a film term, by remaining close whilst keeping one's vision in a "wide shot" and hence maintaining a global image of what is happening. With the linguistic shift that comes with language acquisition, comes a cultural, thought and mentality shift. My aim was to acquire, in as much as it is possible over a period of seven years, the point of view of the Ovahimba in their way of seeing, their weltanschauung, specifically as related to their rapport with the au-delà. In his ethnography, The Igbo of South-eastern Nigeria [17], Uchendu, quoted by his daughter, Chi-Chi Undie, in, My Father's Daughter: Becoming a real anthropologist among the Ubang of Southeast Nigeria [18] suggests on the one hand that the native point of view is still largely lacking representation in the literature of our discipline, and, on the other hand, to acquire ‘living' knowledge of a culture, one needs to be born into it.Tjomihano, Magic and Mahony completing the slaughtering of a goat at the camp.

Excerpt of Rina Sherman filming and Ondjongo dance playing ceremony at the homestead of the Headman of Etanga, from "Ovaryange tji Veya – When Visitors Come", video 45, 2006.

Language Culture and Translation

<16> The objective of this ethnographic study is to interpret, as a passeur amongst those constructing the stage of Ovahimba culture, the fiction of language is represented as a constitutive element of their cultural identity. Such an objective raises questions about the limitations and possibilities of language and translation, as well as the aptitude of the anthropologist to represent a culture precisely and in a manner that is acceptable to people he studied. Having lived outside of the culture of my origins (South African), and working in several languages (English, French, Afrikaans and Otjiherero), I have often been confronted with the questions raised by linguistic and cultural translation, in terms of accuracy and legitimacy. In this regard, documentary photographer and essayist, Wright Morris [19] holds that, "only fiction will accommodate the facts of life" and that, "our choice, in so far as we have one, is not between fact and fiction, but between good an bad fiction." I would add to this that the essential part of our choice in representing other people, lies in a choice between good and bad will. Finally, be it in film, photography or in writing, when in doubt as to what to present or not, the question is whether it is acceptable to the individual concerned. Drawing from a number of disciplines in my work - anthropology, cinema, performance art, music, art, and photography – I constantly question the significance, intricacies and consequences of translation in my work. Working through a translator means that the main interpretation of the culture is that of the translator. Whatever his language skills and his interpretative capacities of the culture in question, the principal preoccupation of the interpreter is to transform what is being said into terms known to the researcher. In Between God, the dead and the wild: Chamba interpretations of religion and ritual Richard Fardon indicates the following with regards to the relationship between researcher and assistant in the field [20]:

The ethnographic and anthropological processes (from research to writing) can be seen as a succession of states of play in the allocation of different types of ignorance and knowledge; often the trajectories of informant and ethnographer intersect. Beginning in ignorance the ethnographer acquires knowledge; but as the informant divulges information so the ethnographer begins to see him as ignorant of his own society.

Whilst I do not agree that the ethnographer starts seeing (or should) the informant as ignorant, but he may start questioning the information as he compares it to information acquired from other sources. He may end up considering the informant's view as one source amongst many of an emerging and constantly changing vision. In fact, once I had learnt enough Otjiherero to understand that words or notions, especially proper names, often contain a condensed personal history or a metaphor, I became far more attentive to the origin and exact meaning words or phrases as used in Otjiherero and Ovahimba culture. Consequently, I applied this questioning to the interpretation and translations supplied by my assistants, always questioning whether the choice of a given word or phrase to translate from the Otjiherero was the exact word or an acceptable equivalent, or the consequence of a limitation in vocabulary in English or Afrikaans and or the reflection of a cultural value or value judgement. A spell of Otjiherero lessons with Dr. Jekura Kavari of the University of Namibia, provided considerable insight into the formation of words and ideas in Otjiherero, specifically on how the change of prefix can make a noun change from one class to another, providing a shift in meaning, which can only be fully understood if the initial use is known.

<17> Following a first reconnaissance trip into the field, in 1996, and a year later, once the project was defined and initial funding in place, I started the search for a field assistant. My principal concern - at the time I did not speak Otjiherero, the language of the Ovahimba – was to find an interpreter who would act as intermediary between members of the community and myself. I worked through multiple sources, such as the cultural service of the French Embassy in Windhoek, colleagues who had been working in the field before me, as well as companies that have businesses in Opuwo, the main town in the Kunene North Region[21]. I contacted those that had done service in Kaokoland [22] in various capacities in the past, such as Chris Eyre, veteran nature conservationist, Ben Van Zyl, former commissioner in Opuwo for the South African Administration and Dr. Eberhard von Koenen, homoeopathist and filmmaker. Chris Eyre worked as a nature conservationist amongst the Ovahimba for thirty years. He advised me to contact, amongst others, the Headman of Etanga, in whose homestead I subsequently settled and lived for seven years. With his characteristic raucous laughter, he waved as I left for the North saying: "Rina, I give you two months out there." Used to advising large television crews or seeing mostly male researchers doing fieldwork amongst the Ovahimba, Chris Eyre seemed to think that as woman alone coming from Paris and used to urban comforts, I would not last long in the field. His reaction was one I would frequently encounter in different forms over the seven years of my stay with the Ovahimba. Most often, people would ask me, sometimes in the presence of the Ovahimba, if I was all by myself out there. I answered that I was living with a family. Some would then say: "Yes but are you the only white person amongst them." The heritage of decades of racial segregation was still present. Ben Van Zyl or Com'Zyl told me how important it was for them in those days to provide an example to the inhabitants by maintaining a neat appearance on field trips. This included an early morning shave with a basin of hot water and a mirror being held by an assistant, as well as having his shoes polished. He used to oversee the hunting expeditions of the South African delegation ministers to their Kaokoveld winter hunting grounds. Dr von Koenen, during his years of studying the plants of Kaokoland [23], developed close ties with the Ovahimba, which lead to him establishing a genealogy of one extended family and to making a film about them. He alerted me to the Ovahimba elders' extensive knowledge of plants, a subject that I explored only cursorily in my research. Fellow researchers, who preceded me in the field, also provided names of assistants that had worked with them.

<18> Through this initial network, I finally found my first field assistant, a young man from Opuwo who had just completed school. During the job interview, I covered questions such as general motivation and language skills, and emphasized the need for flexibility in terms of hours. As he left, he asked me if I had a cold drink for him. Surprised as I was by his request, I nevertheless went inside to get a soda. Through the managers of Nawa Store, a supermarket in Opuwo, I met another young man who worked at Water Affairs in Opuwo. As a scarce commodity in this semi-arid savannah region, water features as a priority in discussions between community leadership and government representatives. This young man was hence acquainted with most of the local leaders. It was arranged that he should accompany the younger assistant and myself on a visit to the various headmen in the western part of the Kunene North region [24]. I wanted to explain the project to local leadership and find a community with whom I could settle for the duration of the project, which at the time was intended to last for six months to a year.

Cultural Background of Assistants

<19> This first trip provided a premise of understanding for my relations with my assistants for the remainder of my stay, which ended up lasting for seven years. Whilst both the elder and younger assistants had both grown up in and around the Opuwo area and were both from Ovaherero families, from the onset, they adopted distinctly different attitudes to the Ovahimba and to myself. The young man from Water Affairs had been functional within a working environment for some years. He was used to accompanying water engineers and development agents from both the public- and NGO sectors into the field. He knew that the success of any operation in the field depended directly on the quality of the relationship with local leadership (headmen and elders). He consistently adopted a respectful and even caring manner in relation to members of the Ovahimba communities that we visited as well as to myself. The school leaver had little or no working experience, and like some of the other assistants that worked on the project after him, it soon became apparent that he did not consider the Ovahimba cultural heritage to be of significant interest. His principal preoccupation was to establish whether he was good-looking enough to become a model. For hours on end, he would question me to find out about the inner workings of a career of which he had only vague notions. Often times I would catch him unawares leaning over the side rear view mirror of the 4x4 to get a glance of himself. His references and aspirations were resolutely anchored in the urban world, as it was accessible through the global communications of television and advertising that reach the isolated north-western town of Opuwo in Namibia. After working on the project for a while, his disinterest or at times disdain for Ovahimba culture became apparent. The basic conflict of interest came from the fact that he grasped the opportunity for employment with me since it gave him the status of an employed person and access to cash. Whilst I clearly indicated in our negotiations that I needed my assistants to flexible since culture does not have hours, come the end of what he considered to be a working day, his main preoccupation was to get ready for the evening. Often thought, there was no "evening", for most nights in Etanga, there was nobody around, even at the store down in Etanga. He was in a catch-22 situation: he was working for someone from the outside world to which he aspired, he was earning cash, which should be giving him access to the world, but this world, in its closest form, Opuwo, was at least a three hours drive away with no transport available. He, like many other assistants and interlocutors I encountered in the field, found it hard to understand why someone who came from the world they aspired to, would give it all up to live with and study a people who reminded them of origins (theirs, at least in part) with which they no longer identified.

Lunch at the camp with members of Nolidep (Northern Regions Livestock Development), Water Affairs and Omuhimba farmer, Uauhareka Tjambiru on the right, following a fodder walk in Wakapawe, near the latter's homestead.

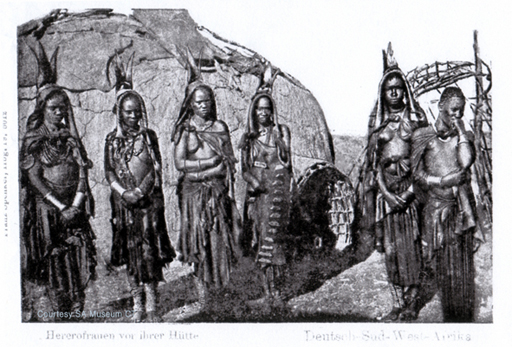

Since only a few Ovahimba – most of which those who worked for the South African army active in the area during the struggle for independence - are literate, my choice of assistants was necessarily restricted to young Ovaherero people of the region that had been to school and that were unemployed, either because they had dropped out of school and did not qualify for most level-entry jobs, or because they were waiting to be admitted to tertiary educational institutions. The Ovahimba and the people known today as the Ovaherero (or Herero) used to be one group and share the same language and belief system. Captions of old photographs of people dressed in old-fashioned Omuhimba dress refer to them as "Herero".

A non-dated old photograph of Ovaherero women in front of their hut, dressed in a style similar to that of the Ovahimba women of today. The caption on the card reads as follows: "Hererofrauen vor ihre Hütte – Deutsch Sud-West-Afrika". Courtesey of the South African Museum, Cape Town.

<20> During the great migration of the Bantu peoples into the Southern parts of Africa, a part of the Ovahimba/Ovaherero remained in the area located on both sides of the Kunene river, whilst another group moved further south into central Namibia and later into eastern Botswana during the German massacres of the Ovaherero in 1904. In the south, they came into contact with German missionaries and became partly Christianized and urbanized, and eventually came to be known as Ovaherero or simply Herero by Westerners or urban Namibians, through omission of the class noun prefix omu-. A small group of Ovaherero live in the southern part of the Kunene Region, many of which around an area known as Kaoko-Otavi. Inter-marriage between the Ovaherero (as well as the Ovakuvale from southern Angola) and the Ovahimba is relatively accepted, and is seemingly more frequent than inter-marriage with other Otjiherero language-speaking groups, such as the Ovadhimba, Ovahakahona, Ovagambwe or Ovatwa peoples. As Jekura Kavari states The Form and Meaning of Otjiherero Praises [25]: "The first pioneers of the study of Namibian African languages were missionaries in the nineteenth century. Their main purposes were to learn the languages themselves and to teach the Namibians to read and to understand the Bible." The transformation from a pastoral people with sacred beliefs invested in cattle ownership to participants in the cash economy, in which cattle are primarily market commodities, has brought about profound changes in Ovaherero society. Prior to independence, the medium of instruction in "non-white" schools in South Africa and Namibia was Afrikaans. Religion was present in daily assembly prayers, religious music instruction, as well as religious education. After independence in 1990, English became the language of instruction in Namibian schools. Consequently, the older assistants spoke Afrikaans and limited English, whilst the younger assistants spoke mostly English. Whilst all were first language Otjiherero speakers and some could partially understand the variants spoken by the other groups, all were not equal in their understanding of the idiom and expressions used by the Ovahimba, especially the metaphorical expression used by the elders in praise poetry, the principal vehicle for historical narrative of their oral tradition.

Reading Between the Lines

<21> The Ovaherero and the Ovahimba speak the same language and share the same belief system. People from both groups say the two cultures are identical, and some refer to the Ovahimba as Ovaherero, as if they are a part of one cultural group. However, through the initial interpretations of language and culture provided by my first assistants in the field, most of which were Ovaherero, I became aware of the need to decode their translations in order to discern the possible meanings of the spoken word or other forms of expression as transmitted to me. Several levels of reading came into play at once, potentially attributing a variety of intentions to the initial expression (Omuhimba person), the intermediary explanation (Omuherero assistant) and the final understanding (foreign researcher) of any single emanation. Depending on the Omuhimba individual, the initial expression may already to a degree be an interpretation of what he or she thinks I should know or even what I would want to know about a given topic. Depending on the level of ease with himself and his own culture, the Omuhimba speaker and the foreign researcher, the interpreter will transmit more or less of what was being said and more or less accurately. Some may at times add complementary knowledge on certain topics if they dispose of such. If their culture is quite far removed from Omuhimba culture, they may feel less compromised in translating delicate matters, especially those in which the Ovahimba take the foreigner to task (colonial or racial issues). In this case however, their interpretative capacities of the metaphorical language used by the Ovahimba, especially by the elders and almost exclusively in praise poetry, may be limited and sometimes misleading. Finally, the intellectual disposition of the researcher himself intervenes as a factor of understanding. His or her training, and hence research methodology used to access, record and process field data, will to a large degree determine the way in which collected data will be processed and presented. However neutral the ethnographer may try to be, field data will inevitably be moulded to fit the form in which it will be presented, for example as a reflection of participant anthropology or as a comparative study, to name but two possible approaches. What he decides to include or exclude is the essential determining factor of the vision he will eventually transmit of the people he studies. Over and above grappling with my own vision, constant effort was required to discern between what was expressed, what the interpreter understood, what he or she considered important for me to know and what aspects of the Ovahimba culture could be transmitted without compromising his or her relationship with the individuals concerned or without shocking me.

Kapi helping Kakaendona and Kapandi to extract red iron oxide stones from a mountain near Kaoko-Otavi. The women grind the stones into powder; add fat and perfumed plants to taste to make the otjize unction that they use to cover their bodies.

<22> The case of one assistant who had relatives in the area is exemplary. Although he grew up in Kaoko-Otavi in the South in an Omuherero family, his mother's brother (frère uterine) - who just happened to be one of the richest men in the area - lived near Etanga. This assistant stood to inherit cattle from his uncle and was keen to renew and strengthen relations with him. Finding employment in the Etanga area allowed him to look after his personal interests. During the dry season, the uncle has his cattle post in Etanga. At this time I had given this assistant the assignment to make drawings of specific everyday life- and ritual situations, in relation to what I had been filming. Each morning, he would take his materials down to the riverbed to make drawings of scenes happening around the waterholes. Sometimes he returned with nothing but a few vague lines on a page. It turned out that he was being drawn into the cattle farming activities at his uncle's nearby cattle post. I later learnt that he ended up having a child with one of his uncle's adopted daughters.

<23> Most of the assistants had been to school where they had been exposed to urban- and Christian religious culture, conveyed preconceived ideas of what they could transmit to me about the culture. At times I would request more in-depth information. Often, their second round of responses would reflect distinct religious- or urban readings of given situations, and in some cases even a certain level of rejection toward the Ovahimba culture and lifestyle. One day, one of the assistants drew my attention to a group of young girls who were on their way to the store down in the village of Etanga. "Look, he said, these girls are going to the café bare feet." One of the girls was said to be his current girlfriend. She was of from a mixed Ovahimba/Ovaherero descent and cross-dressed between Ovahimba - and urban dress depending on whom she was interacting with socially. In this case she was accompanying a group of girls from the Headman's homestead that either walked bare feet or wore tyre sandals. On this day, she was dressed in urban clothes and wore no shoes, as did some of the Ovahimba girls. In his comment, the assistant indicated the importance he attached to physical appearance in specific social situations, in this case, going down to the shop on a Saturday afternoon, a time when many young people gathered there.

Two young girls from Nuku's homestead in Wakapawe visiting Etanga, here in the riverbed at the end of the month when people from the vicinity flock to Etanga for the distribution of the old-age pension.

In the same way, Ovahimba children, when enrolling for the local school, are encouraged and at times forced to wear urban clothes or some form of uniform, and to remove visible signs of Ovahimba cultural belonging, such as jewellery and hairstyles. Whilst the Church and the State were separated under the rule of racial segregation in South Africa (and Namibia) [26], the educational system was known as Christian Higher Education, with separate departments for whites and non-whites. In both systems however, religion was omni-present, such as daily assembly opening with prayer, religious songs being taught during music instruction and regular visits by pastors to schools. Moreover, from the early presence of the church in Southern Africa, school education was provided by missionaries. For many people from older generations of the Apartheid era, missionary education was the only access they could have to education and some form of dignity in a dispensation that showed little consideration for them and their culture. Education hence often came with religion and with it access to acceptance, dignity and a recognised identity. This is the case with Ovahimba children: once they enter the school system, they return home singing songs evoking another world, the world of hierarchic authority (police) and religion, to name but a few elements. When education enters the Ovahimba society, whether the children go to boarding schools in urban centres or whether education comes to them in the form of mobile schools, with it comes the values of the urban world in terms of behaviour, dress and a shift in their belief system, either gradual or complete, that is, abandoning their own belief system for the culture of Christianity.

Conflicting Aspirations

<24> Most of the assistants employed on the project The Ovahimba Years over a period of seven years fitted into the category described above, that of young people that were schooled or semi-schooled, urbanised or semi-urbanised and Christianised with a greater or lesser attachment to ancestral beliefs. The principal problem experienced in my relationship to them, was an attitude of varying degrees of dismissal toward the Ovahimba culture, considered to be rural and old-fashioned and in the worst cases even to be primitive and backward. During the filming of Shake Your Brains – Kurakurisa Ouruvi (2000), a film about alcohol abuse in the Kunene Region [27], I interviewed the nurse at a local first-aid clinic. He was the first Omuhimba person to complete his school leaving certificate and went on to qualify as a medical assistant. He became urbanised in the process but maintained close ties with his community and to his relatives in the Ovahimba community. The question of health and sexually transmitted diseases is important when considering the effects of alcohol abuse. When I asked the nurse about sexual practices in the Ovahimba community, he refrained from providing a detailed explanation and preferred to refer to such as "these cousin things", that is, youthful sexual activities and experimentation amongst relatives.

Tjomihano Tjisuta and Magic Mberurua assisting Gerd Rossler of Radio Electronic with the installation of the satellite telephone antenna.

The personal and professional aspirations of the assistants were firmly anchored in urban culture as opposed to the rural ancestral culture of the Ovahimba. By accepting employment on the project they were attempting to improve their living conditions, by acquiring skills and increasing their buying power by earning money otherwise hard to come by in a region rife with unemployment. Whilst motivated in the beginning of their tenure, most eventually proved to have insufficient working culture, a reluctance to accept responsibility and an unwillingness to hold irregular hours as required by the study of the Ovahimba cultural heritage. Initially, the assistants, in varying degrees according to each person's individual disposition, would be amenable to holding flexible hours. But soon it transpired that they expected to hold regular office hours and expected to be free after hours. This expectation was never clearly stated, perhaps because the requirement for flexibility in terms of holding irregular hours was clearly explained in job interviews and stipulated in working contracts. To a degree, the work entailed being flexible and susceptible to informal socialising with the Ovahimba whenever the occasion presented itself. Members of the Headman's homestead and of the community would arrive at the camp at all hours of day and in times of need even at night. Sometimes it was just to visit and spend time and sometimes they came for a specific reason. I had an open door policy and would interrupt work in my office tent whenever someone came to the camp. At times, such visits turned into extensive sessions, with tea or coffee or even meals served. They required the presence of assistants, who were reluctant to interrupt their other work – transcription and translation for those who were literate, and camp management for those who were not – and join us under the palaver tree. I considered the conversation that ensued from these visits to be important, as they would provide information and often provided an opportunity to take photographs, film or record sound. During these visits, some of the assistants would lose their focus and become bored, and find it hard to return to the discipline of work once the Ovahimba left.

Musisi Humu (standing) and Vekumba Tjambiru (bending over) helping with the slaughtering of a sheep given by Venakamunua Tjambiru (right) and his wife (left), in the company of Kamboo (centre) and Uauhareka Tjambiru and Kamboo. The sheep was slaughtered and eaten one afternoon on the side of a funeral attended in Omutati.

<25> At times, the rituals and ceremonies that I filmed would last for several days and would require for the team to be available almost day and night for three or four days. On occasion, the Ovahimba would draw the assistants into participating in the rituals. Depending on the assistant's relation to the community, he would be more or less open to being drawn into participation. For the assistants who were part of the community, involvement was normal. Whereas assistants who had vested interest in the community, accepted to partake, but became impatient during the periods of apparent non-action, especially at times when he was involved in translating or drawing activities. The Ovahimba thought nothing of asking anyone present to contribute, including myself, even though I was mostly busy filming or photographing. Such involvement ranged from holding still a sacrificial animal, preventing bottles of alcohol intended to be drunk at a later stage of the ritual from being drunk too soon or being drawn into mining for red iron oxide stones [28] in the mountains whilst I was filming the activity. After filming, I would transfer the rushes onto a preview format (VHS) and would screen it to the people concerned. Such screenings often took place in the evening and required the presence of at least one assistant to help with the installation and supervision of equipment. At times we would hold evening screenings of films I brought with me from France. These screening came about when the Ovahimba one day said to me: "We are tired of seeing things we already know, we want you to show us images of things we don't know." Upon my subsequent return from France, I brought a range of films with me, of which some of Jean Rouch's films, such as Cimetière dans la falaise (1950) and Les maîtres fous (1955), but also films such as The Mask of Zorro (1998), Prêt à porter (1994) and Shaka Zulu (1987). Initially all the assistants attended the screenings, since they had not seen the films before. But when, night after night, the Ovahimba requested their favourite films to be screened, that is, The Mask of Zorro and Shaka Zulu, they became reluctant to be on duty to assist me with the screenings. Being removed in the remote location of Etanga from their social networks, some of the assistants liked to have their evenings free to socialise. The young women however, became reluctant to mix with them once they understood that the assistants were unwilling to share some of their employment benefits with them. Since the assistants did not form part of their kinship groups, the young women could not hope for more than passing gain from them. In time it became increasingly difficult for my assistants to socialise within the community. They needed to be free in the evenings to visit homesteads in an ever-widening circle in an attempt to satisfy their needs. One day, an assistant said to me: "Doctor, I need a woman, I'm weak, if I don't have a woman, I don't have strength, I can't work." This sub-text of the relationship between my assistants and members of the Headman's homestead eventually became a part of fieldwork in the sense that we were all living together and complaints and conflicts inevitably overflowed into what could be considered research proper. It also informed the research by making attitudes apparent on both sides. For example, one day, it appeared that the Headman's wife, Omukurukaze had been placing pressure on some of the assistants without me knowing to provide her with provisions from the kitchen. There had been endless problems with food disappearing from the kitchen tent, in my absence or even when I was at the camp, and I had taken measures to prevent it, simply stating that whoever is involved or present when food disappears will be expected to replace it in full, including transport costs. When Omukurukaze could no longer persuade the assistants to heed to her demands, she lashed out at them: "You are poor, you have no cattle, that is why you are sitting here under the tree, waiting for the Otjirumbu [29] to give you orders." From an Omuhimba point of view, anyone who did not own cattle was poor and stupid, and consequently subjected to working for white people. Omukurukaze's attitude showed a reverse snobbery; whereas the assistants and generally people from a rural background that have become urbanised to a degree, look down upon the Ovahimba as rural and uneducated. But there is a prevailing attitude amongst the Ovahimba that anyone who leaves cattle raising behind and gets school education and eventually ends up working in the urban world, no longer has his own identity and self-pride.

Authority and Time

<26> In different ways, authority came into play in the roles occupied by my assistants and myself, in relation to members of the community and to one another. The interpretation of my assistants varied according to individual personality and language skills. For some, it was clearly only a job that turned out to be quite boring. They did not share my interest in spending hours with various sectors of the Ovahimba community, especially at times when nothing of interest seemingly happened for hours or even days on end. These assistants only provided translation and execution of other tasks upon request and tried to both regularise their hours of intervention and minimize the number of hours worked as much as possible. Such assistants, having acquired notions of working culture in their education and experience, were in some ways the most reliable since they were more objectively positioned in relation to their function. In the long run, they also seemed to have less of a problem with accepting the authority of a woman employer, however contradictory this may seem. It would seem that their familiarity with the workplace provided the necessary references to respect the framework of their jobs. They found it easier to hold regular working hours, and to have breakfast before they started working in the morning, so as to have an uninterrupted stretch of work.

James, the Omugambwe builder looking on as Kapandi (standing) and her team of women add a layer of outase or cow dung to the veranda in front of the camp. In the back ground Musisi is fetching water to mix the cow dung with ash.

The Ovahimba assistants were used to eating their first meal at around 10 or 11 AM, as is the custom in their own cultural framework, that is, after they have done some work in the mornings and were feeling hungry. However, the general lack of enthusiasm of the Ovaherero assistants in relation to Ovahimba lifestyle and culture at times made it problematic to involve them sufficiently in a process that ultimately depends on the quality of human contact and exchange. Toward the end of the period during which I worked with field assistants, one of them said to me: "This is a nowhere project, nothing ever happens." This remark was made following my return to the camp after three weeks of absence. The assistants had been left with an individual list of tasks for each, an attendance schedule to ensure that there would always be at least one person at the camp, as well as a food schedule to make sure that provisions would last until my return. As often upon my return, assistants only attended to a few of their duties. From what I could gather, camp attendance was not consistent during my absence, and even though I always left more than enough food provisions, there was nothing left upon my return. I understood that I was really the main motivation for the project to continue and evolve, and that I could not blame them for not having the same level of involvement. I had thought though that being well paid and learning knew skills, would be sufficient motivation. It aspired that I was wrong, and that the dynamic of the project only really worked when I was present. This realisation was one of the reasons that lead me to dismount the camp and continue my work without the use of assistants half way through my stay in the field. The camp and the assistants was not of much use to the project if I did not have freedom of movement at all times. It was too much to expect from a group of young people that had not been prepared in their education or their general culture to understand and support such an endeavour. In the end, in order to continue, I had to make way with the constraints of the infrastructure of the camp, and hence also with the assistants who were employed to maintain it.

<27> Throughout my seven-year stay in the field, I would often hear dismissive remarks from various quarters about the apparent lack of action, of which from assistants, but also from colleagues in the field as well as from journalists [30]. People who had not lived through the time cycles of the Ovahimba, could not see what was happening and perceived times of quiet as times of nothingness. In Otjiherero, time and space is expressed by a single word, oruveze. Once the initial period of astonishment had come to pass, which to some degree any newcomer experiences, I too had to work through the moments of boredom and disappointment with the apparent "lack of action" in the field. As my fieldwork progressed, I had come to the point where the Ovahimba "time-space", the apparent nothingness had become the very "thing" that I was observing and even had become a part of. I had inscribed myself into their "time of life" to such an extent that I no longer perceived it as great stretches of nothing happening. In fact, life had become so dense up on the hill of Ohere [31] at the Headman's homestead that I welcomed the quieter moments of lazing around in the slight breeze under the palaver tree, even though I was aware of the fact that a great deal was being said and was happening during these times.

Excerpt from a four day long spirit welcoming ceremony for Kukatepa, the Headman's youngest son, Pokanjo's wife and his niece, Vuaanderua's daughter, URL: http://www.ovahimba.info/files%20various/movingtoy.html

<28> From being almost entirely dependant on my assistants for communication with the Ovahimba, as I learnt the language, I became more and more autonomous in my movements, except in cases where precise translation was needed, for example customary law cases or any other contractual agreement. Being able to speak the language, however poorly initially, allowed me to establish a relationship with people without the presence of an assistant. As my language skills improved I started moving about on my own, leaving the team at the camp to work on the transcriptions and translations of the video and sound recordings. However, it remained problematic to leave the assistants alone at the camp. I would often return finding the camp in disorder, with no or little work done and no food supplies left or with good stolen from my office tent. I would be forced to take disciplinary measures, which would create a tense atmosphere at the camp, and of which the Headman, who considered the camp as part of one house, disapproved. Furthermore, in order to accept working for me, most assistants seemed to have based their relationship with me on that of maternal respect. When my manifestation of authority became too harsh in nature, they would resist it. Work beyond the homestead was a mostly male domain. The contradiction was that I was doing work traditionally associated with men; most ethnographers, filmmakers and photographers that venture into this part of the world are men, and if women do come they are most often accompanied by a man. To run the camp, I had to learn to repair all sorts of things, the vehicle, solar panels, computers, cameras, etc. This was work readily identified with a man than a woman. In relation to the Ovahimba men, my work provided an entry into their world; they allowed me to film rituals and ceremonies in which only men participated, and on occasion gave me meat reserved for male consumption. But the assistants were working and living with me on a permanent basis. They came from a culture of dual descent in which their mothers played a prominent role and had distinct authority in well-defined areas of life and especially of the general running of the homestead. I would have preferred to have a more distant relationship with them, but time and again, they would resort to me as if to a mother; all their problems became mine, even the problems they were having with me. I learnt to constantly measure my attitude toward them, to coax them along into accepting the priorities of the project, rather than to oppose their occasional unwillingness to cooperate. Eventually, managing them, keeping them busy, and dealing with each individual's personal problems took up too much of my time. I ended up spending more time on tending to my camp managers than on data collecting or processing. The very reason why I had constructed the camp, with complete word- and image processing and film and video editing facilities, was so that I could process data in situ whilst continuing to do research. In retrospect, for reasons going beyond the difficulties of managing a research station and assistants, fieldwork and data processing are best separated in time and space. Toward the middle of my stay in the field, when for a variety of reasons I stopped working with assistants, one of them said to me: "We thought that you were an old woman and that we could ‘play' with you, that we could make you tired you, but you have showed us that you are stronger than us, that our games did not tire you; you are our okakurukaze [32]", or wise old mother.

<29> In some ways, the assistants from Ovahimba or mixed Ovahimba and Ovaherero backgrounds or experience, for example those of Ovahimba backgrounds that have attended schools, were the most interesting in terms of their participation in my fieldwork. However, they also presented the most complex and difficult cases to manage, simply because the various aspects of our relationship directly concerned their relatives within the immediate and extended community. Three cases are worthy of mention here: Tjomihano, from Omirora, who was a relative of Kazinguruka, the Headman's wife, and who, other than a few phrases of Afrikaans, spoke only Otjiherero; Vekumba, whose family was from Omutati, a settlement situated some eight kilometres south of Etanga, who had been "adopted" by Ndoozu from Omblisizaho, the son of the former Headman, Vetamuna, and a nephew of the Headman, and who had been to school in Opuwo; Musisi, who grew up in an Ovaherero environment in Kaoko-Otavi, obtained his school leaving certificate in Opuwo, but whose uterine uncle, Nuku, was a rich farmer or omuhona from Wakape, and whose eldest son Toori had become a friend of the project. Although from different backgrounds and having different relations to the members of the Headman's family and members of the community, all three had one thing in common: their keen interested in the culture, local news and doings, albeit for personal reasons.

<30> In 1998, by coincidence Tjomihano passed through the homestead of the Headman as I was pitching my first tent under the palaver tree [33] that subsequently became the pivotal space of the project. He was unmarried at an age at which most Ovahimba men are married and had families and he would come to Etanga regularly to spend time with his conquests. It was on such a day that he came across our little group busy pitching my tent next to the tree. It was a large tent that hung from a poled protective roof structure and it was quite difficult to pitch.

Pitching of the first tent of the camp in the shade of the Shepherd's Tree at the homestead of the Headman of Etanga.

As Tjomi arrived, we were trying to hoist the tent up to hook it onto the roof structure. With his tall strong body, he lifted the tent and hooked it onto the roof, saying: "Weermag, Tjomi weermag!" meaning "Army, Tjomi army", suggesting that he had the strength of a man that had been to the army, in this case the South African Defence Force who recruited trackers amongst the Ovahimba during the war for independence. It later turned out that Tjomi was only too pleased to bide time with us because custom prevented him from arriving at young woman's homestead before dark, that is once several messages have been passed back and forth to establish whether he would be welcome or not. The next day, he returned requesting to be employed on the project. Pressed at the time to understand what was happening around me, I did not want to appoint someone with no command of English or Afrikaans. He insisted and I eventually acceded to his demand. Soon Tjomi was an integral part of life at the camp. He was illiterate but had a keen understanding of the nature of my work. He indicated several elders who knew Ovahimba culture to us. He could at times be tough in his reactions to people, as was the case with a young French student who had come to live and work at the camp in exchange for food. Once it became apparent that the student was reluctant to provide his fair share of work, Tjomi started to complain and one day did not lay a place for him at the table, making it clear that if he did not work like the rest of us he was no longer welcome.

Tjomihano Tjisuta aiming to fire with the mock AK47 that he cut from a piece of wood.

<31> Much later I learnt that Tjomi's first words, "Tjomi weermag!" was the first expression of a forged identity. Throughout his stay on the project, he fostered the image of himself as a former member of the Army, spending hours telling us stories of kontak [34] with the SWAPO forces. During the last months, Tjomi's behaviour gradually changed. He started drinking, often would not work, and started stealing. He would take unauthorised leave of absence from work, and the other assistants started giving me indications that all was not well between him and certain members of the community. One day he arrived with an ondikwa or decorated baby carrying leather sling and insisted that I buy it. I did not collect objects from Ovahimba material culture, but this piece was old and well preserved. The next day, a woman from Nuku's family arrived at the camp insisting that I return her ondikwa to her. In the presence of the woman, I gave the ondikwa to Tjomi demanding that he return the money I paid for it. The ondikwa represents fertility, and given the sacred nature of the object, the case was transferred to the Headman. Tjomi was condemned to a pay a fine of a head of cattle to the family. Furthermore, he would be held responsible for any misfortune (death) that would come upon their homestead for a period of three years. Following this unfortunate incident, Tjomi's behaviour deteriorated and ended up in him one day stealing all the bottles of Zorba, an aniseed flavoured spirits that I kept for interviews with elders who always requested something to drink to "loosen" their tongues. Another customary law case ensued and Tjomi was fined to pay me a goat and to receive a number of eight lashings. I protested against the idea of corporal punishment. The elders modified it to an ox to be given to the community. This incident finally broke my confidence in Tjomi and a month later I gave him notice. His dismissal provoked an aggressive reaction from him toward members of the Headman's family and myself. Knowing the camp very well, he sneaked in at night and opened the goat enclosure, the garden gate allowing the chickens to devour the small plants and worst of all in this arid area, he opened the taps of our reservoirs letting all our water run to waste. Some weeks later, Tjomi's life took a tragic turn when he was struck by lighting whilst sitting amidst of a circle of people outside the Headman's hut. I was away on a short trip to Paris at the time. Several explanations were given to clarify his death, one of which that I had left a day before to make it look as if I was not involved but that I was somehow responsible for his death. Months later however, someone else provided a different interpretation: A bad spell had been cast onto Tjomi over an old and unresolved quarrel regarding the heritage of cattle between relatives from Omatjivingo and Angola.

Tjomihano Tjisuta shortly after joining the project as camp manager. Here with Katjekere and Touree, the son he had with her before she got married. The Headman of Etanga inherited Katjekere's mother after her husband passed away. Katjekere spent a part of her childhood at the Headman's homestead and was by all accounts a member of the family.