Reconstruction 10.4 (2010)

Return to Contents»

The Outside of the Document

On et al. and the maintenance of social solidarity / Baylee Brits

Abstract: Through an analysis of an exhibition by the art collective "et al," this essay explores questions of the document, documentation, and documentality in reference to questions of "extraordinary rendition" and "the state of exception" in relation to the United States’s responses to the bombing of the World Trade Center in New York. The ontology of the document in the postmodern era is, paradoxically, one of both maintenance and rendition.

Keywords: visual culture, rhetoric, philosophy

<1> The installation entitled maintenance of social solidarity, by the elusive New Zealand artist [collective] et al., [1] was shown at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney in mid-2009. Located in a darkened section of the gallery and partitioned off from other exhibitions, maintenance of social solidarity was divided into several sections that were partially demarcated by wire fencing, and appeared to emulate a disused, abandoned or otherwise empty military or political space. The installation consisted of an accumulation of images, apparent found objects, furniture and most significantly a large projection of a recorded or streamed “film” of Google Earth, which showed the putative “black sites” at which the US carried out its program of extraordinary rendition of terrorist suspects. This installation was presented by the Art Gallery of New South Wales as preoccupied with “mind control” and the practice of extraordinary rendition undertaken by the US military as part of the “war on terror” and et al.’s website describes the subject of the exhibition as: “[a] Summary of proceedings of the meeting of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe held in Paris on 7 June 2006.], referencing an actual meeting by the said council. This essay focuses on the specific means by which the assemblage of collages, objects and surveillance technology that make up maintenance of social solidarity create a certain ambience that is identifiably military or political. Specifically, this essay claims that this ambiance is achieved via the deployment of various documentary conventions, and thus attempts to elucidate the specific stakes in this culmination of the documentary aesthetic. The maintenance of social solidarity will be used as an occasion to theorise Hito Steyerl’s concept of “documentality” in the context of extraordinary rendition. This essay begins with a close reading of Walter Benjamin’s Thirteen Theses Against Snobs, where Benjamin schematises a generic divide between the artwork and the document. I will argue that this divide is also an ironic separation that presages a depoliticization of the document, and will develop this contradiction at the heart of the Theses to articulate the perceptual experience and political significance of a contemporary art installation which performs a rendition of the generic document in an art (gallery) setting. This political move is rendered literal in the installation through two transports: firstly the isolation of the frames or generic supports of the document to create a sense of pure “documentality” and secondly the movement of the document into the art gallery. Read together, Benjamin and et al’s generic accounts of the document provide an articulation of the political manipulation of the ontology of the document that occurs in the state of exception invoked at the time of Benjamin’s writing,[2]and in the context of the extraordinary rendition dealt with in maintenance of social solidarity. The implications of et al.’s “rendition” will finally be brought into relief in terms of the relationality between politics and aesthetics, as schematised by Jacques Rancière.

<2> Crucially, this textual response aims to do justice to the conceptual and syntactical demands made by the multiple permutations of medium and authorship in this installation. In other words, this analysis attempts to maintain a critical solidarity with the difficulties in writing about this installation, taking these grammatical difficulties as symptomatic of the conceptual revolutions achieved by the installation. It is important to note, even prior to a discussion of the elements of the installation, the significance of the artist name and choice of installation title. Given that et al.’s installations have been widely acclaimed and exhibited,[3] the anonymity in the nom de plume seems less an attempt to escape persecution than to present an equivocal relation to authorship. The choice of moniker generates an irremediable grammatical ambivalence, whereby any attempt to refer to the artist(s) only defers and disseminates any attempt at naming.[4] Likewise, the name of the installation; maintenance of social solidarity, similarly refuses the stability of a coherent referent. Every reference to the installation obscures attempts to describe it, in that the naming makes reference to an unspecific, presumably political, process: the maintenance of social solidarity. Both the artist’s name and the installation title are presented as decapitalised, resulting in a textual refusal of pronouns. This serves to further generalise and despecify, thus generating a degree of critical ambivalence. The installation is effectively produced by constant others and acts as an injunction for the spectator to speculate as to exactly what social solidarity is being maintained, for what purposes and by whom, or alternately, what program of maintenance of social solidarity is being critiqued here. [5]

<3> Benjamin’s Thirteen Theses Against Snobs consists of two parallel lists containing contradictory and dialectical formulations regarding “the artwork” and “document.” This list includes such oppositions as:

III. The artwork is a masterpiece / The document serves to instruct

V. Art works are remote from each other in their perfection / All documents communicate through their subject matter. (66)

These oppositional articulations of the effects and purposes of artwork and document provide a percipient account of the form of attention given to each, or the supposed generic differences in meaning creation between the artwork and the document. Benjamin’s table of oppositions must be contextualised by his profound distrust of the “aura” of the artwork; these theses can be read as a radical gesture against the auratic dimension of the work of art. The aura, which Benjamin characterises as “the unique apparition of a distance, however near it may be” (“The Work of Art”; 23), is the quasi-mythic uniqueness and authority of a work of art by virtue of its place within a ritual or tradition. However, there is also a second radical gesture traceable in the theses. These distinctions, written “against snobs,” articulate a generic discrepancy but also express a rarefication of the purpose of the document, which is precisely what allows it to be refigured or reconsidered as an artwork. In the Theses, Benjamin implicitly locates the means by which the distinction between artwork and document begins to decay. The act of isolating the purposes of an abstracted, generic document contradicts the very existence of the document if it is true that the document becomes communicable, and is therefore realised, through its “subject matter” rather than a “perfect” communion of form and content as in the case of the artwork. This ironic movement to define “the document” suggests a contradiction in the distinction between art-work and document: the document is in fact made to participate in a “remote” economy of “perfection,” like the artwork, by virtue of its abstraction to a genre. In the Theses Benjamin constructs a frame around the document, if only a minimal one, to delineate a divide from the art work, yet this act of framing, even as a divestment of aura, introduces ambivalence into this opposition. The implication of a circular aesthetic in Benjamin’s delineation of the generic document thus raises the prospect of an aesthetic of truth production in the same move that seeks to divest the document from the artwork. This “shift” to a “documentary” aesthetics is alluded to by Paul Ricouer, who traces the ambivalence in the abstracted “notion of the document”:

In the notion of a document the accent today is no longer placed on the function of teaching which is conveyed by the etymology of this word – it is derived from the Latin docere. And in French there is an easy transition from enseignement (teaching) to renseignement (information); rather the accent is placed on the support, the warrant a document provides for a history, a narrative or an argument. (67)

The alteration in the function of the document is here construed as a matter of accent, a shift from the information produced by the document, to what it reproduces; a shift from educating or informing to providing authorisation for a discourse or a relationality. This “support” or “warrant”, with all its interpolative mystique, is the frame of the document: simultaneously the scaffolding which articulates a politics of the document, which in the Theses divests the document from the artwork, and the device by which the document acquires an aura.

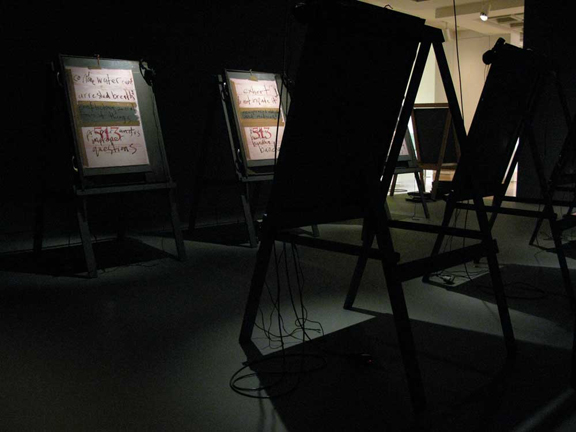

<4> These frames, which introduce the splinter of the aura through the assertion of the generic, are replicated in multiple and even contradictory forms in maintenance of social solidarity, producing the overwhelming sensation of the warrant crucially without every presenting a document. maintenance of social solidarity can be best characterised as an assembly of several layers of documentary conventions, literally collaged and stacked together. Yet these documents, transplanted haphazardly into an art context, are devoid of any information or subject matter and identifiable as documents only through these various “warrants” which constitute a documentary aesthetic. One section of the installation consists of a row of art easels with poster-sized collages. Attached to the easels are large headphones that play either political speeches or messages, most notably from George Bush and Osama bin Laden, spoken by computerised, monotone voices. Whilst the recorded speeches espouse political rhetoric from vastly different contexts and standpoints, the monotone of the voices precludes any attempt at establishing who is speaking and thus neutralises the rhetoric and prevents it from becoming effective as such. The installation also contains a bare, wooden trestle table with a chair and a lamp: an empty work desk. On the table there are stacks of documents; both the desk and the documents are suggestive of some process of analysis, or the production of information, but this is inferred rather than confirmed or actualised. Architectural or urban plans, without indication of which actual sites they refer to, are stuck on the walls, and in conjunction with the presence of the desk these plans appear as part of some kind of spatial analysis. Notably, the only identifiable “information” – information tethered to locations – is that of the sites of extreme rendition shown on the Google Earth projection.

<5> These various framing elements that make up maintenance of social solidarity suggest a secret, temporary or compromised strategic space without specifications: the installation simultaneously suggests a military headquarters, an insurgent’s bunker, and a political base or command centre. The mise en scène created through an assemblage of documentary conventions, a spatial collage of visual and auditory cues, indicates that this is a strategic space, yet it does not establish a reason or purpose for the strategy, nor an identifiable authority that may lend coherence to the scene. These highly differentiated spaces are all evoked and collapsed into one ambiguous sensation as a result of the deployment of multiple and profuse aesthetics of the document.

|

Figure 1 |

<6> This aesthetic intervention becomes particularly explicit through a close analysis of the posters in the installation. The easels with the poster-style images provide an incredibly literal interpretation of the transportation of the document in the art gallery (see Fig. 1). Easels here denote work in progress at the same time as providing a kind of fine art framing of poster-sized collages of various “documents.” The posters are framed with packaging tape, which makes it seem as though they also functioned as the sides of boxes or crates, an effect that provides another literal allusion to packaging or travelling. The first layer of the posters always appears to be a textual document of some form, either the front of a report or what appears to be an enlarged excerpt from a book or essay. Some of these documents, which effectively provide the “canvas” of the posters, seem to be fragments of an account of Buddhist logic published by a Russian author in the 1930s.[6] This first layer is overlaid with words, phrases or notes in what appears to be juvenile handwriting, which contrasts with the formality of the textual documentation below. These notes reference waterboarding, misinformation, and contain phrases like “abstain from conforming,” and “a baseless opinion”; injunctions or ideas that are primarily impactful and convey passion and rebellion without a specific agenda, target or circumstance. In this sense, the posters are constructed from a series of documentary techniques - indicators of authenticity and authority - that enable the document to be abstracted from its subject matter or purpose, to be framed. This framing can be articulated as a political act through recourse to Hito Steyerl’s concept of “documentality.” Steyerl writes:

I call this interface between governmentality and documentary truth production ‘documentality.’ Here scientific, journalistic, juridical or authentistic power/knowledge formations conjoin with documentary articulations – as we saw it exemplified in Powell's speech. […] The truth politics of the US administration is a perfect example of the documental interplay between power, knowledge and the organization of documents. (“Documentarism”; n.pag.)Here, Steyerl references Colin Powell’s speech to the U.N. Security Council, where Powell testified to the existence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. [7] Steyerl identifies this speech as exemplary of documentality or “documentarism as politics of truth” (“Documentarism,” n.pag.), in that Powell’s claims were based not on substantial evidence but on the authority and evidential quality of the intelligence information displayed at that meeting. As a term, “documentality” succinctly describes the production of affect that indicates the authority of the document, specifically the role of affect in the consolidation of authority independent of subject matter. For Steyerl, documentality is the mode of truth production located foremost in the experience of power – in the sensed or affective component of governmentality. The production of a documentary aesthetic thus articulates the juncture described by Steyerl, whereby the documentary form – as a genre that attempts to establish facts – intersects with Foucauldian governmentality. [8] A documentary aesthetic, on Steyerl’s terms, is the point at which the document becomes simultaneously a tool of political management and truth production, implicating the one in the other. maintenance of social solidarity can be said to reproduce a certain documentality in that the installation reproduces a documentary aesthetic, soliciting the affective capacities of the document without necessarily establishing facts and information.

<7> The audio recordings, played through the headphones attached to the easels, are exemplary not merely of documentality as accent, or as the auratic element of the document, but, importantly, as a production of documentality. The computerised voices that reiterate speeches by Bush and bin Laden eliminate all natural speech and tone of voice that would indicate context and add emphasis and expression to the speech. The hyperbolic political rhetoric of the recordings becomes dissociated from any specific agenda or situation and thus becomes generic and meaningless; the format through which these speeches are played back is absolutely incongruous with the political specificity and persuasiveness that the rhetoric is intended to achieve, in effect nullifying the speeches. This process of annulment occurs in exactly the same way that the arbitrariness of the book or report covers and the defacement of these by the handwriting signify conflicting or oppositional relations to information. The unspecified document, the handwritten slogans, and the recordings of political rhetoric mounted on these easels - both the language of the government, the language of research and the language of the resistance here – are rendered out of context, in another voice or without voice, providing an excessive multiplicity of isolated documentary techniques without documents. This culmination of the “documentary without documents” results in a combination of sensation-al authority and indexical ambivalence that is the dual effect of an isolated aesthetics of the document. This dissonance between authority and ambivalence can also be described as a tension between legibility and intelligibility, where the authority and significance – the “import” - of the documents is immediately available to the viewer, yet remains intellectually incomprehensible. Thus what we have here is not simply an foregrounding of documentality so much as the generation of a pure documentality: a documentality that takes the place of the ontology of the document rather than characterising the ambivalence of the document between teaching and warrant.

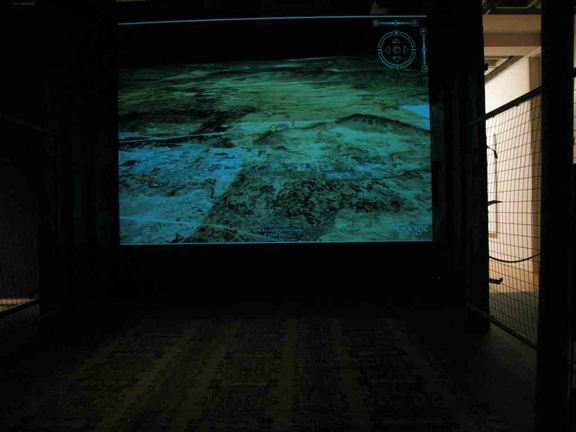

<8> This affective production of a pure documentality is extended rather than alleviated in the effect of the Google Earth projection, despite the projection being the only element of the exhibition that presents seemingly coherent and interpretable information. The Google Earth projection provides an interesting counterpoint to the posters, which were tactile, immutable and multilayered constructions often referencing the past. Google Earth is, instead, a real time mode of surveillance or mapping the earth; it brings an immediacy of information to the space that the posters on the easels did not possess (see Fig. 2). If there is an aesthetic of the documentary, the Google Earth projection might be said to provide a formalist harmony or balance to the installation in that it extends and consolidates the assemblage of documentary projections by providing an instance of up-to-date and continual surveillance. The Google Earth software allows users to emulate a pilot flying over the earth, directing the digital “flight” through visual geographical data by clicking on locations in order to “zoom in” and access increasingly detailed imagery. This attempt to describe the projection already encounters the complexity of re-presenting this software in an installation setting: whilst the projection is best described as a “film,” what we are presented with is clearly not “footage,” as what is being shown is a recorded search through a database. The projection appears as a film without originating or being projected from film, introducing a paradox at the core of this documentary medium. This paradox of media is coupled with a paradox of information transmitted by this media: what is being shown specifically in the projection are simulated “flights” over the locations that were used as “black sites” in the US’s program of extraordinary rendition. This was the program, at times also called “irregular rendition,” whereby the US would extra-legally transport suspected terrorists to countries that allowed torture or methods of interrogation that approached torture. The “paradox of information” or the “documentary without documents” is reproduced in this case not because of an absence of information or subject matter, as was the case with the posters, but because the process of extraordinary rendition itself serves to undermine the production of stable intelligence and indisputable evidence or proof. “Evidence” or “information” is undermined in the first instance because it remains unclear to what extent the program of extraordinary rendition actually occurred: despite maps of purported “black sites” being available for public access on Wikipedia, the US government has never validated this information or responded to allegations of practicing extraordinary rendition. [9]

|

Figure 2 |

<9> This contradiction is abetted in that Google Earth, a real-time publically accessible objective surveillance technique, is being used to show or make visual, make observable, sites that were both outside sight and law, and as such the entire condition of their viewing is the fact that these black sites are now defunct. The real-time satellite imagery here shows images of juridically invisible sites (at least beyond the scope of the US judiciary) where an unconfirmed military-political practice is purported to have occurred in the past. This is a simultaneous mapping of extra-legal political practice (of what could also be phrased as an illegal-legal practice) and an entirely pointless exercise, literally revealing nothing and providing only an affective or sensational function. The information presented appears in the form of a paradoxical incoherent or unintelligible subject matter by virtue of its extra-legal and classified status, yet presents completely legible forms of truth-production (the currency of truth-production and objectivity possessed by satellite imagery). Both the posters and the Google Earth projection featured in maintenance of social solidarity thus offer multiple forms of legibility whilst resisting intelligibility, the capacity to “make sense” of the aesthetic cues of the documents provided. The documentary aesthetic provokes unspecific affect, retaining an undecideability or unresolvability, in that the space appears equally as a strategic military site, a political headquarters, an activist hideout or insurgents’ bunker.

<10> The descriptions of the installation put out by the gallery as well as by et al., which characterise the installation as one that “investigates mind control in its various manifestations” and provides a summary of a meeting by the European Committee on Legal and Human Rights respectively, thus refer to an affective rather than informative production, an artistic decision that corresponds exactly to the broader subject matter at issue: the practice of extraordinary rendition in the war on terror. Adopting et al.’s particular affinity for literal re-enactment, one can re-read the phrase “war on terror” in a literal sense, understanding it as a reference to a war simultaneously on or of a certain form of affect. This phrase also contains a consequential paradox: the war presumably seeks to eradicate a sensation that would only come after an attack or other act of violence: it is a “pre-emptive strike” – to use military terminology – against the resulting affect, but not necessarily real possibility, of an enemy attack. What is also suggested by this paradox is that “the war on terror” is, in a self-perpetuating but also self-negating fashion, a war against the affect provoked by violence.

<11> et al.’s affective critique of the war on terror can thus be theorised on its own terms: through the development of a conceptual schema that derives from an artistic displacement of the processes of extraordinary rendition. The act of “rendering documents” might be an appropriate means to describe the action of the installation: et al. provides a kind of extraordinary (out of context or displaced) rendition of documents. “Rendition” is the state of the document, the action of the document: to evidence, maintain, affirm, without a transcendent ontology or final addressee. This is precisely Benjamin’s point on the politics of the document as antithetical to the aura of the artwork. Concerned with subject matter, as Benjamin notes, the document is always capable of being misread and this fallibility is precisely the location of the politics of the document. Here, “rendition” of the document is in fact conceived in the artistic sense of the term, which refers to drawing as well as more broadly to an interpretation or performance – a version – and is thus a suitably ambivalent mobile theoretical term to articulate the political stakes in the documentary aesthetic.

<12> Thus, et al’s extraordinary rendition of documents – a rendering outside – mirrors the political process of extraordinary rendition which replaces rendition as the ontology of the document with the aura, in other words: removing the subject from the frame. Pure documentality is a more radical affective rendition of the document that stems from documentality, the inherent capacity of the document to exceed its subject matter, which I earlier discussed as the double nature of the frames in Benjamin’s Theses. In the context of the Google Earth projection, this pure documentality constitutes the “extraordinary rendition” in that the installation traces the shift in the ontology of the document from that which renders, supports, a function that might maintain a social solidarity, to inaugurating a social solidarity or situation, less a rendition than a transcendental, inaccessible authority – an aura - that arrives from an outside. It is important to note here that for Steyerl documentality also describes the possibility of a subjectivation under what Steyerl calls the “Empire of the Senses.” Using the example of Abu-Ghraib, Steyerl notes that: “In an era dominated by fear and sensation, power operates more than ever within the senses. It is increasingly sensible, it has penetrated perception as such, it has become overwhelmingly aesthetic” (“Empire of the Senses,” n.pag.). If the ontology of the document in and of the state of exception is divested of politics and is exclusively about power then this occurs, as Steyerl makes too clear in her discussion of Abu Ghraib, through an aesthetic and perceptual experience that is precisely tied to the aura that Benjamin sought to oppose the document to in his Theses. In this sense, the extraordinary rendition of the document is also the transport of the document from its original place in Benjamin’s Theses into the auratic domain of art.

<13> It is important to stress that Steyerl’s conceptualisation of documentality articulates vulnerability inherent in – and as I have suggested, possibly presaged by - Benjamin’s distinctions between the art object and document discussed above, in that documentality articulates the presence of an affective documentary form as imbricated in the very functioning of the indexical documentary form. The frame is in fact the corrosive that breaks down the column divide between the two columns of Theses, a corrosive which transports the document into the domain of art (extraordinary rendition), yet the frame is also what articulates the politics of the document for Benjamin (rendition). Extraordinary rendition precisely obscures this point, implying a transcendent authority and producing an aura as the comport and import of the document; the frame used to articulate a generic concern with subject matter now becomes the subject matter itself. This is what is described in Steyerl’s “Empire of the Senses” when she notes the appropriation of sensation as a tool of the police: where a population can be manipulated through modulation of affects – notably shock and fear - which are capable of producing a communal sense of vulnerability and hence political docility. The document, here, no longer contributes to the maintenance of social solidarity, but participates in its dissolution when it undergoes the process of extraordinary rendition.

<14> This capacity for the affective to arise out of and obscure the indexical function of the document provides a unique conception of the interaction between politics and aesthetics, brought into relief when contrasted with Rancière’s theorisation of the presence of aesthetics in politics and vice versa. In Rancière’s terms politics is conceived of as a rupture in the fabric of society, where what was once invisible attains visibility (“Aesthetics and Its Discontents;” 25). In this sense, as a “making visible” or revolutionary establishment of representation, politics is bound up with the sphere of aesthetics, where aesthetics broadly refers to the creation of possible worlds (“Thinking of Dissensus”; 4). Indeed, Rancière locates the possibility of a reconfiguration of the “realm of the sensible” and a refutation of the police control that governs the uniformity and normativity of the realm of the sensible in aesthetics. In parallel to this, aesthetics, as a structure of communal perception, also bears the political implications of a relation between affect and form:

Indeed, a case can be made that in its immediately post-Kantian formation ‘aesthetics’ simply is the name for the displacement of political desire into a philosophical discourse about the structure of production of feelings through form. (Osborne; 7)

Whilst this formulation clearly articulates the mutual implication of politics and aesthetics in terms of conjunctions between affect and form as well as revolutions in visibility and representation, it does not directly account for the potential of a “politics of aesthetics” – an “Empire of the Senses” – where the political capabilities of aesthetics (a rupture in the realm of the sensible, the emergence of truth) come to enact the function of the police.

<15> Steyerl’s conception of documentality occupies a complex and interesting relation to Rancière’s mapping of the relations between politics, aesthetics and the activity of the police in maintaining the realm of the sensible.[10] This is because, on the one hand, documentality is a function of the police in that it is a means to maintain a hegemonic imaginary (a realm of the sensible). And yet documentality crucially achieves this, on Steyerl’s terms, via an intersection between aesthetics and politics, the meeting of these two spheres in the process of truth production. Here, the mutual implication of these two spheres in fact becomes the capacity of the police.

<16> This theoretical dialogue between Steyerl and Rancière facilitates a critical interrogation of the activity of documentality in et al.’s installation. In maintenance of social solidarity this conjunction between politics and aesthetics occurs in the barrage of documentary cues that make up the installation, which provide an affective authority but no real “political” rupture in the sense of the production of new information or representations. The documentality presented in maintenance of social solidarity through a rendition of documents can be said to perform a replication of the law of the police as far as it determines visibility, where visibility is assumed to also imply information value and truth production. Yet maintenance of social solidarity crucially does not reproduce the function of the police or become complicit in the processes of stabilising the realm of the sensible by virtue of the fact that it produces documentality through their own secondary artistic “extraordinary rendition” that moves the document into the sphere of art.

<17> The first extraordinary rendition of the document, et al’s literal response to the condition of the document in a state of exception, is the creation of the documentary aesthetic, whereby documents become capable of inaugurating social solidarity rather than providing a maintenance of social solidarity. The hinge that produces a critical relation to the police manipulation of aesthetics-politics relation, however, is the secondary extradition of the military process of extraordinary rendition into the gallery space. This process allows us to identify aesthetics as the element of the documentary that allows it to become subject to extraordinary rendition (in et al. and the US military’s terms). In other words pure documentality – an aesthetics of the document operative independent of its indexicality - provides the rationale that produces documentary conventions as liable to or vulnerable to rendition. The radical undecidability of an unspecific military-political ambiance in maintenance of social solidarity reproduces the aporia of the documentary in the context of extraordinary rendition independent of a specific police end. In this sense, the installation almost comes to ironically enact the kind of rupture that Rancière articulates as the action of politics. However, this rupture crucially does not produce representation, as Rancière imagines it does, but here provides a nuanced perceptual experience that does not capitulate to the construction of visibility, a perceptual over simplification in a time where political ends are achieved via legal precedents such as extraordinary rendition. Instead, maintenance of social solidarity provides a radical rupture in the very possibility of the political event as Rancière conceives it, articulating the perceptual experience, the affective exposure, of a politics of invisibility rather than visibility.

<18> Here we have a theory of documentality, indeed pure documentality, in the context of the state of exception or the practice of extraordinary rendition. The political practice of extraordinary rendition requires an extraordinary rendition of the document, which is the assertion of the frame or warrant of the document as its ontology. Indeed, the practice of extraordinary rendition as a sovereign enforcement of invisibility, the rendering-outside of the state of exception, functions in terms of the document as the inaccessible and (perpetually) unique power of the aura. Thus Benjamin’s radical gesture of 1930, the assertion of the politics of the document against the aura and in terms of instruction and subject matter, in terms of a maintenance of social solidarity, becomes radical once more. However, it is crucial now to foreground the generic instability – the irony and ambivalence that I argued was present in the Theses – which allows Benjamin’s demarcation and constitutes this divide as threshold of risk. Resistance to the pure documentality of the state of exception requires a return to the politics of the document through another act of framing, returning to an ontology that demands not deference but an analytic relation.

WORKS CITED

Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2009: et al. maintenance of social solidarity : Art Gallery of New South Wales - Archive. Art Gallery of New South Wales. Web. 30/01/2010.

Bal, 2006: Mieke Bal. "Intention." A Mieke Bal Reader. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2006. 236-63. Print.

Benjamin, 1979: Walter Benjamin. "Thirteen Theses against Snobs." (1928), in One Way Street and Other Writings, London and New York: Verso, 1979. 65-66. Print.

Benjamin, 2008: Walter Benjamin. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version.” (1935-1936) The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media. Ed. Michael W. Jennings et al. Boston: Harvard University Press, 2009: 19-55. Print.

et al., 2005: "maintenance of social solidarity II: et al." et al. Web. 30/01/2010.

Davey, 2009: Edward Davey. “End the Rendition Cover Up”, The Guardian, 18/08/ 2009. Web. 30/01/2010.

Foucault, 1991: Michel Foucault. “Governmentality”, in The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, eds. Graham Burchell et al, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991, pp. 87-104.

Gutteridge 2009: Clara Gutteridge. “Obama’s Rendition Shame”, The Guardian, (August 26 2009), online edition. 30/01/2010.

Marshfield, 2004: Undine Marshfield. "Et Al. NZ Artists for Venice Biennale 2005 Win Prestigious NZ Award, The Walters Prize / e-flux.” E-flux. November 25, 2004. Web. 30/01/2010.

Osborne, 2009: Peter Osborne. "Undoing the Aesthetic Image." Radical Philosophy 156 (July / August 2009): 7-8. Print.

Rancière, 2003: Jacques Rancière. "The Thinking of Dissensus: Politics and Aesthetics." Paper Presented at Conference Fidelity to the Disagreement: Jacques Rancière and the Political, London: Goldsmiths College, September 16-17, 2003.

Rancière, 2009: Jacques Rancière. Aesthetics and Its Discontents. Trans. Steven Corcoran. Cambridge and Malden: Polity, 2009. Print.

Ricoeur, 2006: Paul Ricoeur. "Archives, Documents, Traces." The Archive. Ed. Charles Merewether. London: Whitechapel, 2006. 66-69. Print.

Stcherbatsky, 2003: Theodore Stcherbatsky. Buddhist Logic Part Two. 1932. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2003. Print.

Steyerl, 2003: Hito Steyerl. "Documentarism as Politics of Truth." Transversal EIPCP Multilingual Webjournal (May 2003): n.pag. Web. 30/03/2010.

Steyerl, 2007: Hito Steyerl, "Empire of the Senses: Police as Art and the Crisis of Representation." Transversal EIPCP Multilingual Webjournal. (June 2007): n.pag. Web. 30/03/2010.

Wikimedia Commons, n.d.: "CIA Illegal Flights." 21/04/2009. Web. 30/01/2009.

NOTES

[1] “et al.” is the name of an anonymous artist or art collective from New Zealand, who notoriously do not reveal their identities or give interviews. For the sake of coherence, et al. will be referred to in the plural in this paper.

[2] Here I refer to the constant “state of exception” used to assert sovereignty repeatedly over the duration of the Weimar Republic, in which Benjamin was living at the time of writing the Theses.

[3] et al.’s work has been exhibited at large, publically funded Australian and New Zealand galleries, most notably the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Additionally, et al. received the 2004 Walters Prize, New Zealand’s most prestigious art prize, and represented New Zealand at the 2005 Venice Biennale. See for instance: e-flux, 2004: http://www.eflux.com/ shows /view/1673; accessed 30/01/2010.

[4] This occurs on the level of meaning as well as graphology. The fact that “et al.” is an abbreviation and is thus marked with a period creates graphic complications: sentences that close with the artist’s name result in unintended ellipses and there is a literal distancing created between the artist’s name and its possessive form in that the word must be interrupted with both a period and an apostrophe.

[5] It is likely that this title may also be an implicit critique of relational art, as expounded by Nicolas Bourriaud. As should become evident in the present analysis, art which self-consciously attempts to create social relations is not immune from participating in the disciplinary regime characterised by Hito Steyerl as the “Empire of the Senses,” which achieves control through the modulation of affect. See below.

[6] The text referred to is: Stcherbatsky, 2003.

[7] Colin Powell presented the “evidence” of the existence of WMD in Iraq to the UN Security Council on the 5th of February 2003.

[8] See: Michel Foucault, 1991.

[9] A map of several purported black sites is available at: Wikimedia Commons, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CIA_illegal_flights.svg; accessed 30/01/2009.

There is an exceptional amount of contradictory media reports on extraordinary rendition; regarding US responses to allegations of extraordinary rendition, see: Davey http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/libertycentral/ 2009/ aug/17/rendition-afghanistan-bagram-torture; accessed 30/01/2010, and Gutteridge, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree /libertycentral/ 2009/aug/26/obama-rendition-cia-prisons-us; accessed 30/01/2010.

[10] In conjunction with this, Steyerl makes her own critique of Rancière’s distinction between politics and aesthetics. See: Steyerl 2007: http://eipcp.net/transversal/1007/steyerl/en; accessed 30/03/2010.

Return to Top»