Reconstruction 11.1 (2011)

Return to Contents»

Decotitles, the Animated Discourse of Fox's Recent Anglophonic Internationalism / DT Kofoed

Abstract: My paper examines the radical, popular reconception of the subtitle's status initiated by films like Tony Scott's 2004 Man on Fire, Timur Bekmambetov's Night Watch [Nochnoy Dozor] and its 2006 sequel, and Danny Boyle's 2008 Best Picture winning Slumdog Millionaire. Subtitles have been redirected from their customarily subsidiary, external position to become a central aspect of the filmic mise-en-scene. The establishment of anti-conventional decotitles represents the possibility of a stabile third term in the debates over subbing versus dubbing. A new aesthetic paradigm has emerged—one which places emphasis not on translation and ventriloquism, a confrontation with the foreign, but on the graphic text as a signifying unit of filmic representation, utilizing the foreign merely as an instigating excuse to create a unique visual representation.

Key words: Television & Film, Transnationalism & Postnationalism, Visual Culture, Translation Studies

<1> While not wholly original in their conception or without isolated precursors, within the last six years a quartet of high-profile releases from Twentieth Century Fox and its specialty-film unit Fox Searchlight has initiated a radical, popular re-conception of the subtitle's status in its previous distinction between inter- and intra-lingual contexts—as graphically additive captions and as linguistic translation. Beginning with Tony Scott's 2004 Man on Fire, rising to prominence in the 2005 international release of Timur Bekmambetov's Night Watch [Nochnoy Dozor] and its 2006 sequel, and nearly unavoidable in Danny Boyle's 2008 Best Picture winning Slumdog Millionaire, subtitles have been redirected from their customarily subsidiary, external position to become a central aspect of the filmic mise-en-scene. The kinship of these titles to both comic book lettering and our commonplace online multimedia experience is not to be dismissed, nor should these films’ coincidence with the widespread use of digital filming and processing be overlooked as a generative factor. An examination of the (formerly sub-) title's newly graphic character and heightened narrative signification as integral to the shot's composition, proceeding from theories of graphic narrative borrowed from comics scholarship, displaces the traditional debate between dubbed and subtitled modes of viewing foreign films, undermining and replacing the ideological conventions of the translating practice. The establishment of anti-conventional decotitles—a neologism this essay serves to define— represents the possibility of a stabile third term in the debates over translation of trans/international cinema for the domestic American audience, whose own English-language films are themselves engaged with this same intercession according to the terms of its formulation. Though consciously begun as a means of marketing foreign language material to popular domestic markets, aimed at the films' acceptance outside of limited exhibition in the art-house circuit, and regardless of their success as such, the significance of the decotitles’ challenge to cinematic orthodoxy extends beyond the strict confines of the marketplace—they cannot be pigeonholed as a mere affect of genre. The kinetically highlighted subtitles developed through this body of films present a vital avenue of stylistic and narrative evolution for cinema as a whole.

<2> To assert a radical reconception here, the provenance of this new aesthetic of subtitles must be clarified, as it admittedly does not sprout whole cloth in a parthenogenic miracle of innovation. The graphic, interpretive potential of text in film is almost co-terminous with film itself. With even a cursory examination of silent era films, the omnipresent intertitles reveal a varied and sophisticated sense of both pure design and the semiotic productivity of text, that which exceeds simple linguistics. Abé Mark Nornes’ critical history of subtitling and dubbing, Cinema Babel, offers the figure of Hitchcock as exemplar of this typographic sophistication, an aggregate cross-signification for temporal and thematic emphasis of the text's surrounding visual elements (104). Yet as Hitchcock is remembered for his directing rather than his titling, it is preferable to refer to the intertitles of better known films, for which the bookends of Weimar German Expressionism are more than sufficient. Robert Wiene's 1920 The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is notable for its highly stylized intertitles, and the climactic incorporation of text into the mise-en-scene proper, as Caligari chases the refrain “du musst Caligari werden” across the frame. In the 1927 Metropolis of Fritz Lang, intertitles often directly reflect their referent visuals, as descending lines of text mirror the preceding elevator's motion, or the dynamic animation of letters that bleed or sweat before emanating rays of light adds another layer of signification to the film's dense visual style. Nornes cites the subtitling of Lang's M as representative of conventions that adapted subtitles to the specific cinematographic composition, akin to post-war Japanese cinema, in which variable placement was held to “complement mise-en-scène and movement [that] depended on narrative as well” (171). Of course, a lineage of the subtitle is not limited to this Axis or periodization. Various essays in Atom Egoyan and Ian Balfour’s 2004 critical omnibus Subtitles offer examples of the manner by which “alternative cinemas, including avant-garde and accented cinemas, have continued to experiment with on-screen titling as an expressive, narrative, and calligraphic component,” such as the work of Mekas, Trinh, and Rozema (114). While Rozema’s 1991 short film “Desperanto” offers its subtitles free rein of the screen space, their direct interaction with the character establishes a parodic play on subtitling conventions which, though much imitated, runs counter to the narrative-translative function of subtitles utilized in the films here under consideration (Egoyan and Balfour 66-7). Subtitles in “Desperanto,” as well as more recent films such as Neveldine and Taylor’s 2006 genre-piece Crank, are positioned wholly within the diegesis of the film such that they may be read by characters themselves. This distinct phenomenon, while interesting, is neither functionally equivalent to nor of the same lineage as decotitles, which retain the traditional non-diegetic quality of the subtitle, regardless of what else may have changed.

<3> The ideological power of subtitles is inextricably bound to their graphic depiction—given their definitional excision of the aural, subtitles are a purely visual structure. Scott’s Man on Fire occupies a privileged position with regard to our films in both chronology and reference. From a simple opinion “that subtitles are boring,” Scott—a pedigreed action director, filming a major studio funded film with international stars—explodes the signifying potential of subtitles in popular genre film through conceiving them as “kind of a character in the scene” (Scott, interview). As the film is set in Mexico City, a certain amount of Spanish-language dialogue is unavoidable even in an American production, driving the subtitles to one's immediate attention. Rather than occupy a bottom centered position in the frame, superimposed onto a perpetual foreground plane of perfect, unobstructed visibility, from their introduction the subtitles are not only given to variable placement along the vertical and horizontal axes, but are positioned within the shot’s depth of field, such that characters and objects may move before the subtitles, obscuring them from the reader’s gaze. As the film progresses, subtitled text is subject to manipulation for affective resonance, including size variation in proportion to the volume or narrative emphasis of the actors’ delivery. The text is often given an animated production, appearing in sequence as the text is “typed” onto the image or as the aural dialogue progresses, sliding in and out of the scene. The traditional, translating purpose of the subtitle is directly questioned, as characters speaking in accented English are selectively subtitled, until even Denzel Washington’s mixed language dialogue is transcribed according to purely aesthetic considerations during emotionally heightened scenes (see Figure 1). This non-translative doubling of the dialogue with its textual equivalent marks a radical reconception of a text’s potential function in another otherwise typical Hollywood production, an inescapably heightened awareness and assertion of the visual nature of the subtitle.

Fig. 1. Emphasis through textual distinction in Man on Fire.

<4> The drawing of lineage between this “Big Fox” production and it subsidiary importation of Bekmambetov’s Watch films through the subtitles was noted at their American release, perceived by the press as a strategy “to help those subtitles slip down more easily with mainstream viewers” (Felperin 79); for each film “Fox’s international version shortens the Russian original by a few minutes, but adds the same eye-catching animated subtitles” (Brooke 53). As all dialogue except the opening and closing voice-overs remains in its original Russian, the omnipresent subtitles here conform to the traditional translative rubric, yet through sheer numbers exceed the attention-grabbing profile of Scott’s earlier experiment. The provenance of Bekmambetov’s subtitles is, however, distinct, imposed not by directorial vision but according to the distributor’s production; it should be noted in passing that Bekmambetov’s subsequent English-language film Wanted retains moments of on-screen textuality even as it eschews subtitles—such as the protagonist smashing a keyboard across a man's face and loose keys, teeth, and blood fly towards the camera in slow motion to literally spell out the character's unspoken “fuck you”—evidence the director has internalized the perceived successes of his imported series. Fox Searchlight executive Stephen Gilula, head of distribution and chief operating officer, has in multiple interviews publicly assumed credit for the subtitling of both films. As reported in UK’s The Guardian, the move to install these animated subtitles began with an uncertainty over the films' probable audience, Gilula’s recognition that “[Night Watch] is not a typical foreign film—it does not sit automatically with a typical older art film audience” (Walsh), yet the initial weekend box office was boosted by “art-film aficionados… lured by reviews comparing Bekmambetov’s work to that of Andrei Tarkovsky” (Rosen). In the New York Times' depiction of the executive’s role as “making Night Watch palatable to American audiences,” Gilula becomes the very preserver of an auteur’s craft, since “you don’t take such an original vision of the world… and try to homogenize it” through dubbing. Fellow “Big Fox” executive James Gianopulos further appeals to the age of computer multitasking as warranting this change in cultural transmission, where “watching Night Watch is now an interactive experience,” despite the film's undeniable existence as that traditional artifact mechanically projected before a passive audience (Johnson). The website IndieWire presents a fuller account of Night Watch’s exhibition, noting that Gilula withheld an immediate American release in order to screen its sequel in quick succession that summer 2006 and capitalize on press from its UK and Australian releases and the festival circuit, concluding that “not only were subtitles not a hindrance to [its] record-setting debut [but] they actually may have helped its box-office performance.” Deeming the Russian-supplied English subtitles to be of insufficient quality, Gilula worked with Bekmambetov and American Laeta Kalogridis to develop a re-cut and re-write for the “international” version of the film, adding “digitized subtitles” that he felt “enhanced the experience” (Rosen). The lack of generic conventions for foreign language films outside the art film circuit left open a wide discursive space within which the hyperkinetic form ultimately given to the subtitles is doubly significant as corollary to the film’s style itself.

<5> All the textual effects of Man on Fire, as an established technical and rhetorical baseline, are replicated in Night Watch. Though the subordinate, front and bottom center placement of the traditional subtitle remains as a default position to which the titles periodically return, the sheer number of subtitling effects employed easily distracts the viewer from a quick comparison to any of their immediate precedents.

|

|

|---|---|

Figure 2 |

Figure 3 |

Subtitles fully integrated into the mise-en-scene of Night Watch.

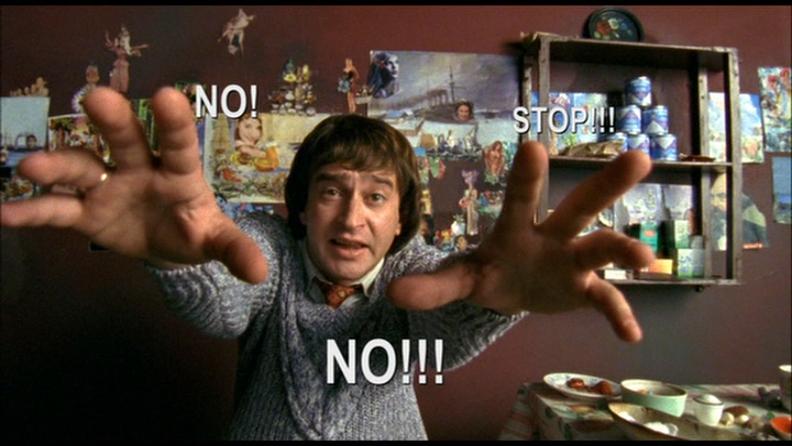

The text jitters and sweeps across the frame, blurring in and out of focus to mirror the disorientation expressed in point of view shots, fits into the negative spaces of the shot's composition, turns blood red in time with the flashing eyes of a vampire's sudden spike of rage, or is occluded by a closing door. Two of the most striking textual moments occur in the first pair of scenes to follow the prologue. In the secondary, intermediary prologue, the protagonist Anton is coerced into magical infanticide, but recants after the ritual has begun; as a mysterious power violently flings his body backwards, his slow-motion cry of negation—in compensation for subtitles typical condensation of exclamation—is multiply rendered around his figure, filling the screen space with textual repetitions of his singular vocal act in variously sized figures. The words as text are placed in motion analogous to that of their speaking body and seem to strike the rear wall simultaneously, breaking the cohesion of the word as constituent letters break apart, dissolving immediately before the shot is cut (see Figures 2 and 3). A myriad of less imposing textual effects follow, including the omnipresent embedding of the subtitles within the shot’s depth of field, as character and object movement alternately reveals and conceals their presence (see Figure 4). The next scene, establishing the narrative present, offers the most frequently noted textual effect.

Fig. 4. Occlusion of the subtitle by foreground movement in Night Watch.

The shot fades into the child Yegor swimming underwater while the subtitles, representing an off-screen diegetic “call,” appear in red letters before his bleeding nose; as he surfaces, the camera tracks his upwards motion, and the subtitle dissipates into wisps of vapor just as the text itself breaks the surface of the water, intermingling with the physical presence of the filmed blood itself (see Figures 5 and 6). The effect repeats in reverse, losing textual coherence as the camera dives to track his figure. A third occurrence of this effect lacks the barrier of the water’s surface tension, yet continues to maintain the text’s appearance within the water even as Yegor, the recipient of this transcribed voice, himself walks beside the pool. Fig. 5-6. The most commented upon subtitle in all of Night Watch.

|

|

|---|---|

Figure 5 |

Figure 6 |

The most commented upon subtitle in all of Night Watch.

<6> The English subtitles for Bekmambetov’s sequel Day Watch [Dnevnoy Dozor] are noteworthy for not having been seen since the film’s original English-language theatrical runs in the summer and fall of 2006. Otherwise known only by reputation and brief mentions in contemporary reviews, they have yet to see release on home video—DVD or Blu-Ray—in any region to date. Though some speculation follows, this textual erasure appears to be a byproduct of the very ease and variety of subtitling inaugurated by digital video formats, paradoxically celebrated by critics such as Mark Betz for the freedom of choice seemingly inherent to the simultaneous presence of “up to four dubbing tracks and thirty-two subtitling tracks” in a single package (“Dubbing and Subtitling” 104). The theatrical subtitles accompanied an edited international version of the film—the same strategy Fox Searchlight employed with Night Watch—while the digital home market releases contain the original Russian cut of the film for which, regardless of its similarity to the final English-language edit, English subtitled prints were never produced. The decision to not re-title the Russian cut would seem to be motivated by financial concerns and the differences in technology used for both theatrical and home exhibition. Subtitling for theatrical release involves the creation of a separate film print in which the text is physically embedded within the image of each individual frame on which it will appear. Though computerization has streamlined this process to allow the possibility of mass-producing film embedded with the textual effects under discussion, an outlay of labor and material is still required as is a separate print on which the text is present. As digital theater projection systems increase, eliminating film, a digital print takes the place of the physical, requiring comparable time for the creation of a digital master. Thus even for home release on DVD or Blu-Ray, the inclusion of English theatrical titles on a Russian theatrical print would require the creation of a new, separate digital master incorporating the text, with all the expense entailed therein. The original Region 1 DVD release of Night Watch is a double-sided disc, one side containing a clean visual print with English dubbing, and the obverse containing the theatrical subtitles embedded in the image—subsequent release on Blu-Ray and DVD of a new high-definition digital master does not feature the embedded subtitles. This presumably cheaper alternative treatment was given to the DVD release of Day Watch, that of player generated titles, the standard format of home release subtitles. The subtitling data is divorced from the image track, such that multiple subtitle files may be present for a single title, added on top of the image by the player hardware in a traditional subtitle form. Thus a single disc printing is marketable across linguistic communities, requiring only the raw translation text data for any given language’s subtitle track. Without delving deeply into financial considerations and market research, however, such comments must remain somewhat speculative.

<7> There is no doubt in attributing a lineage to our final film, Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire. As reported in the Washington Post interview with the director, Boyle assured executives at Warner Independent—prior to Fox Searchlight’s distribution of the film—that his film “will be even more exciting with subtitles,” inspired by having seen the “nontraditional subtitles” of Night Watch (Beckman). Commenting on both the tradition of subtitles and its technology, he quips, “It’s so cheap to do laser printing at the bottom of the screen…but you don’t watch the film—you read the film and you scan occasionally to the actors.” To counter this, he digitally embeds his subtitles within the film, both for theatrical prints and on its various video releases. Eschewing the active motion of Bekmambetov or Scott’s titling, Boyle and title designer Matthew Curtis limit themselves to two effects: first, a variable placement according to character position, “to have the subtitles look more like the dialogue in comic books;” second, to free this placement from a dependence upon a clear background field for legibility, text is placed within colored caption boxes, introducing “a little spark” of color in the mise-en-scene beyond the bounds of realism, without descending into a wholly stylistic realm of abstraction or expressionism (see Figure 7). A mainstreaming of prior textual experimentation, given wide domestic multiplex release, Slumdog nonetheless introduces its own innovative stylization by explicitly referencing comic book captions. This move should not be surprising, given comics' long-established mutual interdependence between the word and image.

Fig. 7. Offsetting color in Slumdog Millionaire's captions.

<8> Much as the soundtrack is not theoretically necessary for film, recent moves in comics theory, particularly in the French tradition, have sought to divorce the word from any essential role in the signification of comics. Yet conventions of reading and creative practice frequently address the interplay between these distinct forms of meaning, and words in comics have a tradition of criticism, for which I will take the work of Scott McCloud as representative of the better sort of creator-driven analysis—the mostly American tradition of pragmatic criticism written by practicing comics illustrators and authors. In his now classic Understanding Comics, McCloud divides the relation of text to image into seven general categories, yet six of these relate to the narrative employment, rather than textual presence, of words, and are thus applicable to filmic dialogue rather than subtitles. Only the underutilized sixth category, “the montage where words are treated as integral parts of the picture” seems relevant, though this term already has a distinct meaning in existing film theory, which renders its direct use problematic (154). Further, McCloud's conception of textual montage is explicitly that of text other than and outside of dialogic captions, rendering its application to subtitles of little relevance. Looking to the French theorist Thierry Groensteen, in The System of Comics we have what seems an explication of the filmic subtitle. Highlighting the tension inherent between flat captions and the appearance of depth in perspectivist art, between the monochromatic text and “illusionist conventions that govern the image,” the surrounding panel is accordingly given hierarchical priority over the caption—both conditions and the resultant relationship are analogous to that of the subtitle (68-70). The transition from subtitles to decotitles supersedes the relation of word to image traditionally theorized in a comics panel. The clearest corollary, explored in McCloud's 2006 opus Making Comics, is the sound effect, those “one-shot inventions you can improvise like crazy,” whereby words “graphically become what they describe—and give readers a rare chance to listen—with their eyes,” that is, “if you don't mind showing-off” (146-7). The singular quality of the comics sound effect remains at odds with the persistence of the subtitle. The decotitle then appears as something unique to film, regardless of its apparent graphic similarity to comics lettering, and must be theorized within its own medium. An understanding of what sets these decotitles apart from traditional subtitles—what warrants another theoretical neologism—must be grounded in an examination of subtitles' existing meaning as an ideological construct of translation.

<9> Having traced this linear development across Fox's Anglophonic international fare, the nature of subtitles in general must be attended to as the ground in which these films act. As John Mowitt observes in his contribution to Subtitles, the question over the textual nature of foreignness in film, about whether the very existence of subtitles are “things one encounters through the eyes or through the ears? Or both?” (387), has plagued the academy throughout its history. The movement of this discussion will begin with the subtitler's status in the attribution of authorship and the dominant convention of an invisible translation, through the problematic relation of this convention to its visual qualities and imperial manifestations towards a more manifest awareness of the ideological stakes of subtitling in general, before returning to our body of filmic examples. Paul Thomas provides a guiding analogy in his jacket blurb for Egoyan and Balfour's essay collection Subtitles: “Subtitles gives us not only a new way to think about film but also a singular design object,” referencing explicitly the presentation of the book as a physical thing, yet also invoking its object of study, the doubled significance of subtitles as a graphic presence inseparable from its medium as film (68).

<10> Along with Egoyan and Balfour's suggestively jacketed collection, Abé Mark Nornes' 2007 monograph Cinema Babel, an expansion from his prior Film Quarterly article “Toward an Abusive Subtitling,” stakes our theoretical guideposts. Man on Fire, Night Watch, and Slumdog Millionaire are unusual in that the translator or subtitler is in each case known and credited. As Nornes notes, “few translators get credit for their essential work” or are compensated as authors with residuals on the film's profit (3), while the participation of credited screenwriters and directors in the translating practice—effectively coextensive with subtitling—is equally rare. Occasionally producers involve themselves at this stage, though it is the distributors and the translators they hire who “take total control and typically cut, censor, and revise the original text” to their own markets (14). As we have recognized on the Watch films, the omnipresence of Fox Searchlight executives in this process is both unusual for the depth of their influence yet entirely typical for the creation of an “international” subtitled cut. The repression of the typical subtitler, or in Fox's case the fetishization of the subtitle as object of interest, both equally “deflect or disavow the erasure of difference and the inequality of languages that the act of translation always threatens to expose” (166). Nornes concludes that “the translators are creating a new text from their original films,” in what amounts to a public call for direct filmmaker ownership of, and creative control over, this process as an artistic necessity (243). If Danny Boyle is the idealized auteur in this regard, still his control of the film's translation extends only into his own language, leaving its myriad subsequent translations for the global cinema audiences to unknown authors. This invisibility of the translator extends beyond the individual's work to translation itself as a spectral aspect of the filmic object as a whole.

<11> Practitioners of the subtitle are aware of the conventional expectations placed upon them, if Henri Béhar’s contribution to Subtitles can be taken as representative. The task of the subtitler is “cultural ventriloquism, and the focus must remain on the puppet, not the puppeteer…to create subliminal subtitles so in sync with the mood and rhythm of the movie that the audience isn’t even aware it is reading. We want not to be noticed” (85, emphasis his). This concealedness of the traditional translating subtitler is essentially characterized in Nornes’ Cinema Babel as an act of a corrupting and violently reductive appropriation of the filmic text by an apparatus “that conspires to hide its work—along with its ideological assumptions…that smoothes over its textual violence and domesticates all otherness.” He quotes director Trinh T. Minh-ha to highlight translation as “the operation of suture that defines… a dominant hierarchical worldview… to protect the unity of the subject: here to collapse, in subtitling, the activities of reading, hearing, and seeing into one single activity” (155-6). The totalizing impact of the subtitled film is that of an additive reduction, an outside colonizing influence with a familiar class-inflection. Yet this imposition of the subtitling translation upon the surface of the film is paradoxical as an invisible visibility, questioning the coherence of film. As Amresh Sinha observes in his essay “The Use and Abuse of Subtitles”, subtitling “is both internal and external, on the borderline between image and voice-on addition, the third dimension, to the film itself. The subtitles come from outside to make sense of the inside… not simply [an] ‘offscreen voice’ that renders the space outside contiguous to the onscreen space. They remain pariahs, outsiders, in exile from the imperial territoriality of the visual regime” (Egoyan and Balfour 172-3, emphasis his). All this despite the recognition that “nothing originally belongs to cinema, ontologically speaking,” establishing a double exteriority of the subtitle as unincorporated device of an always already second-hand medium (173). This entering, the exteriority of subtitles to the translation they effect, undermines the very invisibility of action they are predicated upon, and which they inscribe upon the cinematic apparatus. The visuality of the subtitle in general cannot be left unremarked.

<12> Invisible translation has provided the argument that subtitles are superior to other methods of film transmission despite the incongruous visibility of the titles themselves. Mark Betz’s encyclopedic summary of this debate introduces its counter argument, that the obstruction of the screen space by the subtitle threatens the cinematic composition and mise-en-scene, providing an incomplete translation which nonetheless absorbs the audience’s perception, “undoing the synergy of performance and script… downgrading the impact and importance of visual expression” (“Dubbing and Subtitling” 104). New York Times critic Vincent Cranby is more direct in his critique:

It is undeniable that subtitles alter our perception of any film, which becomes a kind of high-class comic book with sound effects, something to be read while looking at the pictures. Subtitles can shield us from certain banalities as often as they destroy the subtleties. They also distort the image, cluttering the bottom of every shot with strings of words that not only obscure a substantial portion of the frame, but also prevent us from seeing much of what is in that part of the frame not scribbled on (quoted in Nornes 15).

However, this emphasis on visual distortion serves to displace and conceal, in plain sight, the more fundamental alteration of a film as bearer of cultural signification through an overriding/overwriting of its linguistic origin. The invisibility of translation lies not in its imperceptibility, but in the inaccessibility of the language it covers which is simultaneously preserved on the archival soundtrack. The xenophobic imperial gesture of the Anglophonic subtitle must not be overlooked.

<13> Mark Betz, in “The Name above the (Sub)Title,” succinctly states the problematic and stakes of this contradiction, that while “the ‘original’ language of another on the sound track would seem to bind the film to its nation of origin… the subtitles the spectator reads may equally become that language, take it over, colonize it, and make it into their own” (104). The third dimension of film threatens that of the aural as thoroughly as it enmeshes itself into the visual. Regardless of the stock one wishes to place in film as authentic encounter with the other, an ethnographic experience, the foreign sound is hidden beneath the domestic and domesticating text. Rather than mere replacement, as with dubbing, subtitling offers an accessory whose excess overtakes and replaces that which it is meant to complement, a code-switch from the aural to the typographic. The source text is transformed without being wholly lost. Eric Cazdyn, with his Subtitles essay “A New Line in the Geometry,” considers this phenomenon under the rubric of a transformative subtitling, which “seeks to de-limit and de-territorialize the subtitled version from the original…. The original is not only what it was, but… it also exceeds itself.” The political nature of the subtitle is such that every subtitling alters the meaning which the original bears (414-5). National and linguistic specificity is effaced for cultural compatibility, evidencing a multiculturalist attitude that readily admits the foreign under a conception of its self. Within the multiplicity of codes that constitute cinema, as Eisenstein theorized, each level must be estranged from the others, opening cinema to internal strife (cited in Egoyan and Balfour 460). This multiplicity allows the imperial subtitle its performance and the possibility of its own subversion in turn.

<14> In contradistinction to this often unrecognized corruption of the filmic text through the ideological conventions of subtitling translations, Abé Mark Nornes develops through Cinema Babel the alternative of an “abusive subtitling.” Recognizing and redeploying the audience's own textual reading practices to locate the subtitles “in the place of the other,” of the foreign in film, this avant-garde practice avoids “smoothing the rough edges… and convening everything into easily consumable meaning [to] always direct spectators back to the original text” (185). Subtitles unify abuse as graphic and textual experimentation in its “grammatical, morphological, and visual qualities,” foregrounding translation in order “to critique the imperial politics that ground corrupt practices” (175). While the ideology of this alternate practice is as heavy-handed as that which it subverts, the emphasis on subtitles as a graphic entity whose visual quality carries narrative and symbol signification is central to the specific form of subtitles—the decotitle—evidenced by the quartet of films from which this argument began. Nornes' recognition that “conventions themselves can be changed most easily at particular moments in history when the rules governing practices are in flux” is key to theorizing a new break from subtitling conventions in contemporary cinema (174).

<15> The contemporary moment of flux is twofold. First is the birth and growth of digital filmmaking, by which I refer to the past two decades' progression from digital compositing of special effects to the freeing of editing and filming from the constraints of physical film stock and the distribution of film to theatres and consumers. Corollary to this, particularly distribution via video discs and data networks, is the theorizing of a transnational cinema accompanying multinational capitalism. Far from attempting to analyze these developments, it is sufficient to note their presence, if only at a theoretical or discursive level. Virtual cameras and visual effects have rescinded the limitations of physics from a filmmaker’s imagination, while on each level of production, exhibition and consumption appear to be freed from nationalist pressures. In this landscape of permanent technical revolution, conventions of all stripes may, at least in appearance, be challenged. In place of the avant-garde-ist abusive subtitles, conscientiously unconventional though they may be, comes the aesthetic of the decotitle—which can only be considered as something new, only has meaning, in light of the subtitles' governing ideological conventions.

<16> The term itself, ‘decotitles,’ as with all neologisms, begs justification and etymological explanation. ‘Subtitles’ bears its ideological connotations on its surface, being that which is subordinate and inferior within film, appearing beneath the projected image, exterior to the mise-en-scene and beneath comment, a subset of generic definitions. Of course, ‘intertitles’ and ‘supertitles’ have long-established definitions and cannot be easily reappropriated, regardless of the immediate appeal their oppositional morphology holds against to the ‘sub’ of the ‘subtitle.’ The ‘decotitle’ serves to denote the overtly graphic character of a titling practice integrated with the mise-en-scene, suggesting an association with the Art Deco movement, that return to a decorative aesthetic in overtly stylized forms following the deprivations of a Great War (“Art Deco”). Further, this very graphic essence marks the decotitle as both aesthetically and functionally distinct from the subtitle, invalidating the idealization of an invisible translation by plainly asserting the existential fact of the title before the spectator’s notice. One cannot but notice this—often literally—animated discourse, as it is conceived and executed in order to draw attention to itself as equal constituent of the film’s visual signification. While typically translative—an inheritance of its lineage from the subtitle—this function is incidental to the decotitle, which exists so as to signify, independent of the language on the sound track. Man on Fire, the first example of the decotitle, most clearly shows this potential as accent rather than pure translation, accent as both remainder of imperfect translation and marker of distinction within a single language. Yet as the Watch films attest, the decotitle is an extreme example of the imperial subtitle, for which the source language is wholly irrelevant. It is only through English literacy that the decotitle has meaning, only in English that the decotitle exists to be read. The imperial decotitle supplants a dominating translation with a seeming devaluation of the need for translation, even as it serves to execute a translation. The internalization and essentialism of the decotitle within these films marks, to borrow and disfigure Nornes’ terminology, an abusively corrupt textual practice.

<17> As Thomas Elsaesser satirically quipped regarding the marketing of film festivals, “one author is a ‘discovery,’ two are the auspicious signs that announce a ‘new wave,’ and three new authors from the same country amount to a ‘new national cinema’” (99). It is perhaps premature to label the decotitle, as examined through these four films, a new movement or shift in global cinema style. Yet in comparison to existing standards of subtitling, and the underlying ideological assumptions revealed in its practice, it is clear that a new aesthetic paradigm has emerged—one which places emphasis not on translation and ventriloquism, a confrontation with the foreign, but on the graphic text as a signifying unit of filmic representation within the mise-en-scene, utilizing the foreign merely as an instigating excuse to create a unique visual representation. The perception within a major Hollywood studio system of financial and critical success with this practice, evidenced by its repetition, indicates some degree of acceptance by the industrial apparatus of film. The conclusions here must be hedged against future portrayals of text in film—and other media, such as the parallel studio system of American television or it opposite in user-generated online content—whether the decotitle as described has the coherence to emerge as a stabile practice, or marks merely a stage in the continuing evolution of the subtitle as the intrinsic graphic design of cinema.

Works Cited

"Art Deco." A Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Art. Ed. Ian Chilvers. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1998. Oxford Reference Online. Michigan State University Library. 8 May 2009. <http://www.oxfordreference.com.proxy1.cl.msu.edu>

Beckman, Rachel. “An Out-of-Character Role for Subtitles.” Washington Post. 16 Nov. 2008: M05. 4 Apr. 2009. <http://www.washingtonpost.com>

Betz, Mark. “Dubbing and Subtitling.” Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2006. 101-4.

---. “The Name Above the (Sub)Title: Internationalism, Coproduction, and Polyglot European Art Cinema.” Camera Obscura 46 (2001): 1-44.

Brooke, Michael. Rev. of Day Watch, dir. Timur Bekmambetov. Sight & Sound 17.11 (2007): 53.

Day Watch [Dnevnoy Dozor]. Dir. Timur Bekmambetov. Fox Searchlight Pictures, Channel One Russia, 2006. DVD. Twentieth Century Fox, 2007.

Egoyan, Atom and Ian Balfour, eds. Subtitles: On the Foreignness of Film. Cambridge: MIT P, 2004.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Film Festival Networks: The New Topographies of Cinema in Europe.” European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood. Amsterdam: Amsterdam UP, 2005. 82-107.

Felperin, Leslie. Rev. of Night Watch, dir. Timur Bekmambetov. Sight & Sound 15.10 (2005): 79-80.

Groensteen, Thierry. The System of Comics. 1999. Trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: UP Mississippi, 2007.

Johnson, Ross. “From Russia, With Blood and Shape-Shifters.” New York Times. 5 Feb. 2006. 4 Apr. 2009. <http://www.nytimes.com>

Man On Fire. Dir. Tony Scott. 2004. Twentieth Century Fox. DVD. 2005.

McCloud, Scott. Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels. New York: Harper, 2006.

---. Understanding Comics: the Invisible Art. 1993. New York: HarperCollins, 1994.

Night Watch [Nochnoy Dozor]. Dir. Timur Bekmambetov. Fox Searchlight Pictures, Channel One Russia, 2004. DVD. Twentieth Century Fox, 2006.

Nornes, Abé Mark. Cinema Babel: Translating Global Cinema. Minneapolis: U Minnesota P, 2007.

Rosen, Steven. “’Night Watch’ Freaks the BOT; ‘CSA’ Score Well in New York.” IndieWIRE. 23 Feb. 2006. 4 Apr. 2009. <http://www.indiewire.com/article/ night_watch_freaks_the_bot_csa_scores_well_in_new_york/>

Scott, Tony. Interview with Daniel Robert Epstein. Ugo Entertainment. 2007. 4 Apr. 2009. <http://www.ugo.com/channels/filmTv/features/manonfire/tonyscott.asp>

Slumdog Millionaire. Dir. Danny Boyle. Celador Films Ltd, 2008. Blu-Ray. Twentieth Century Fox, 2009.

Thomas, Paul. Rev. of Subtitles: On the Foreignness of Film by Atom Egoyan and Ian Balfour, eds. Film Quarterly 60.4 (2007): 68-70.

Walsh, Nick Paton. “Russian Horror Flick Hopes to Challenge Hollywood.” The Guardian. 13 Feb. 2006. 4 Apr. 2009. <http://www.guardian.co.uk>

Return to Top»