Reconstruction 11.1 (2011)

Return to Contents»

Mapping Desire and Transgression Through Other Languages: Sex and the (Occasionally Multilingual) Provincial City / Karen Rodríguez

Abstract: This article analyzes how a small, conservative city in provincial Mexico uses foreign languages as a partial strategy to map desire and transgression. Drawing on the concept of projective identification and referencing work on the psychoanalytic affects of multilingualism, I examine several other-language texts in the public domain to show how foreign languages create spaces for transgression and the expression of desire. The article speaks to the specificity of multilingualism’s affects and psychic uses in different sites, emphasizing in particular the unique way this plays out in a small city versus a more traditionally defined “global city.”

Keywords: Gender, Sex & Sexuality, Place & Space, Psychoanalysis, Translation Studies

<1> In her reading of the film Chungking Express, Tsung-yi Michelle Huang (2004) discusses how one of the protagonists, a mega-urban flâneur, employs different languages to make the Hong Kong metropolis more intimate, to shrink the city down into a community, and to connect with people. The flâneur in question, a Hong Kong native, is Police Agent Number 223, and Huang situates him as follows:

What he is looking for, an intimate local community, is gone forever from the city. Confronting a heterogeneous metropolis made up of different kinds of communities, 223 still clings to belief in a homogenous social space. Multilanguage proficiency is thus imagined as his magic power of retrieving the lost community: he not only looks but talks while walking. (p. 38)

Agent 223 is searching for a return gaze, and he uses foreign language as a strategy to pursue what he desires, the intimacy of connection. He tries to connect first through one language and then through another in an attempt to carve out a tiny piece of monolingual community. Even though 223’s efforts are not ultimately successful, Huang’s analysis says much about how multilingualism is perceived as a way to achieve this in the large, global city. One could also infer that the city of Hong Kong employs counter-strategies to foreclose being re-imagined and thus re-spatialized into smaller communities. Already a fragmented and multilingual site, the mega-city is not particularly shaken by Agent 223’s introduction of different languages, and its larger space is thus not re-imagined.

<2> But what happens in the case of the small city, where community and intimacy already exist? How does the use of other languages in this context help the now provincial flâneur (or in the example below, flâneuse), do something quite different: namely, escape the sometimes stifling intimacy of a small space by transcending, disconnecting, and searching out spaces and moments of release? How does the small city itself mobilize the affective possibilities of multilingualism? In this article, I explore how the small, Mexican city of Guanajuato employs foreign languages as a partial strategy to project desire and map transgression into particular spaces, in the process reimagining local space as “elsewhere.” I discuss how the adolescent flâneuse reads this as an opening in which to express sexuality and desire, both nominally taboo in this conservative town. However, I underline that despite the existence of this opening “elsewhere,” she cannot relate the otherized space back to the larger context of her life, which leaves local constructions of sexuality unchallenged. Like Agent 223, her efforts to harness the affective possibilities of other languages to transform the local scene are powerless when faced with the dominant status quo of the city at hand. Drawing on the concept of projective identification and referencing work on the psychoanalytic affects of multilingualism, I examine several other-language texts in the public domain to show how foreign languages are used to these ends. The article speaks to the specificity of multilingualism’s affects and psychic uses in different sites, emphasizing in particular the unique way this plays out in a small city versus a more traditionally defined “global city.”

Multilingualism in Texts, Psyches, and Cities

<3> Linguistic Landscape (LL) theorists study the written word as it appears in multiple languages in a public space, arguing that space is symbolically constructed through street signs, names of buildings and statues, billboards, notices, and so on (Shohamy and Gorter, 2009). LL researchers ask who produces what sorts of signs to what ends and for what audiences, examining the power relationships that may be evidenced by this. And they assert that these publically-located texts indicate something about collective identity, with the linguistic landscape “constitut[ing] the decorum of public space” and contributing greatly to a city’s unique personality (Ben Rafael, 2009, p. 42).

<4> What the collective city “writes” through all this public text also says something about local norms and potential challenges to them. Certainly, naming and mapping space through language is tied up inseparably with the representation of self and other. Yet despite the fact that LL research has established the social and ideological role that “other” languages play in mapping a site, LL researchers have paid more attention to the political ramifications of multilingual texts in the public space, than to the affective or overtly psychoanalytical implications of what these texts say about a city’s process to make sense of its cultural others. Nonetheless, we are well aware that multilingualism carries significant affects for their speaking/reading subjects, and that these affects are intimately intertwined with space.

<5> Learning one’s native language as an infant marks a shift from the pre-verbal maternal space to the social, symbolic sphere comprised of a host of others with whom the child can now communicate, thus making language a key element in establishing subjectivity, individuation, and socialization. The spatial aspects of this process have not gone unnoticed. In Freud’s observations of the fort/da game in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), we see the child using both space and language to represent the present and absent mother: with fort, he launches the wooden reel out of sight, and with da, he recovers it, thus using language to symbolize and come to terms with his mother as an other. Psychoanalysts Amati-Mehler et al. concur:

We must take into account that learning to walk also coincides with learning to speak, and therefore with the acquisition of a whole spatial organization regarding separation from the primary object, experiments in detachment, and the possibility of verbal conjunction with the distant object. It is therefore clear that learning to speak in one or more languages means coming to terms with problems of separation… (1993, p. 126)

<6> When individuals “walk” further, travelling to foreign lands, and acquiring multiple languages, the effects on the psyche are complex. The affective connotations of switching languages in everyday life have been brought out in novels (e.g. Alice Kaplan’s 1993 French Lessons and Eva Hoffman’s 1990 Lost in Translation) and in both scholarly and analytical work, which has also examined the implications of analysands’ language choices in different affective situations. Perhaps the earliest study of multilingualism and its psychoanalytic meanings within a therapeutic context is Sigmund Freud and Josef Breuer’s work in the 1890s with Bertha Pappenheim/Anna O, the woman whose hysteria led her to “forget” her native tongue and shift into French, English or Italian. Amati-Mehler et al. note that “hardly anyone in the small group of psychoanalytic pioneers underwent analysis in his own mother tongue, and only in rare cases was the mother tongue the same for analyst and analysand” (1993, p. 23), referencing Freud himself, as well as Margaret Mahler, Melanie Klein, Sándor Ferenczi, Alfed Adler, and Theodor Reik, among others, as part of this group. In their The Babel of the Unconscious (1993), Amati-Mahler et al. undertake a theoretically complex analysis of defenses and other affective possibilities afforded by language choice in different therapeutic situations, considering how multilingual analysands switch languages to distance themselves from past trauma and to disengage from the maternal, among other things. Again, the importance of space is alluded to as shifts in language are analyzed in conjunction with shifts of country of residence. From these brief examples, it is clear that language is both “a social and spatial activity” (Pennycook, 2010, p. 3).

<7> Outside of the analytical setting, Cronin (2000), looking at the emotional aspects of travel and translation, and following Stengel on the role of the super-ego in foreign language learning, has written about the “fear of infantilisation” adults experience when learning new languages. He posits that “foreign language provides a stage, a space for the exploration of another self or of another element of self” (p. 53), which opens up subjectivity and relates it to new spaces. The space-language relationship is further underlined as he maintains that “If travel means uprooting oneself from the familiar, embracing the anonymity of flight, then language difference can further accelerate the move away from the known world of mother-tongue utterance” (ibid). From Cronin’s work, we see the parallel again between geographical space and linguistic distance between native and foreign languages. Psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva has explored questions about second languages and subjectivity as well, and she has contributed significantly to our understandings of the foreigner’s use of language. Drawing on her own transition from her native Bulgarian to French, she discusses the psychoanalytical ramifications of the foreigner’s efforts, successes, and failures in shifting into another language and place (1991, 1995).

<8> Returning to the question of multilingual texts in the public domain, Ben Rafael et al. make the point that while together multilingual signs may appear to be chaotic and conflicting, their collective existence is perceived as a single whole by city-dwellers or passerby who move between all this urban wordage (2006, p. 8). This would seem to be the case in Hong Kong, where flâneurs like Agent 223 perceive a multilingual whole (fragmented and changing as it might be). But what happens in a smaller site where multilingual texts are present, yet not the norm? Are they part of the whole, or do they stand out in signifying something else? Within the smaller, less “global” city context, one can thus ask: Are other-language texts experienced as an intrusion? A threat? An opportunity? What is achieved or excluded by employing other languages? What is at stake, and what are the particular affects of multilingualism in a given site?

<9> The rest of this article explores these questions in the context of Guanajuato, a small provincial city in Mexico, to argue that by languaging city space and sexuality as other, the city attempts to create room for her inhabitants’ taboo desire. I focus in particular on the female urban subject, or the Guanajuato flâneuse, more than on the male flâneur, although their difference should not be overstated. While Mexican women have to contend with traditional split representations of good versus bad women, with sexuality playing the lead role in this division, in the small-town environment of Guanajuato, both men and women struggle against conservative norms. In my analysis, however, I focus on the adolescent flâneuse to represent the young women engaging the multilingual aspects of the city and the texts discussed, though sometimes the gender specificity is less salient than at others.

The City of Guanajuato

<10> The city of Guanajuato is located four hours north of Mexico City, and its population is roughly 130,000. The city has a unique topography that differentiates its layout from other colonial cities which were constructed along a grid design that corresponded to class and race, with power concentrated in the center. Formed like a dented bowl, the city’s physical environment is hilly and twisted, and it quickly and permanently eluded such control. Another consequence of this topography is that from within, there is no visual egress, which contributes to the sense that everything is contained, seen by all, known. Family names and connections are still important, relationships are neither anonymous nor impersonal, and while the city is not homogenous, of course, it is hardly fractured. In short, there is no getting lost in the crowd like Baudelaire’s flâneur or the various flâneurs portrayed in Chungking Express. Notwithstanding this cohesive intimacy, Guanajuato is known as a prime tourist destination, and it is home to a large university, several theatres, and a circuit of small museums. Therefore, it is not a dusty town where outsiders rarely enter; nor are foreigners anything out of the ordinary at this point. Encounters with cultural difference are commonplace both in the media and in daily life. The intersection of small town aspects with more cosmopolitan traits makes the site richly complex.

<11> Despite the fact that the city is a city and not a rural site, as part of provincia, understood in Latin America as anything outside of the capital city, Guanajuato enters into a rhetoric of colonial, quaint, traditional. Provincia has been feminized and to no small extent substitutes as the nostalgic lost maternal for the capital, Mexico City, one of the world’s largest and most chaotic cities. This conceptualization developed as early-mid 20th century intellectuals and politicians struggled to create a national identity that differentiated the nation from both Spain and the all-too-close presence of the U.S. During this process, Mexico as a nation became defined as masculine, a bundle of characteristics symbolized and embodied most clearly by Mexico City, positioned as urban, aggressive, center, forward-looking. Within the masculine national, provincia was correspondingly constructed as female and associated with the past, the peripheral, and the passive (Frey, 2001; Gutmann, 1996; Paz, 1950; Ramírez, 1977; Ramos, 1934; Uranga, 1952). This feminized other of national space is left playing a rather mute yet essential supporting role.

<12> The most well-known indictment of Mexican womanhood, although there are many, comes from Paz’s Labyrinth of Solitude. He constructs women as sexually repressed, and characterizes them as suffering objects of violence, obsessed with motherhood to the extent that it impedes their full development as adults. Furthermore, he claims that national identity, represented by men, depends upon this dialectic to maintain its own subjectivity. Paz envisions woman as simply “a reflection of masculine will and desire” (1961, p. 35). He argues that women are incapable of having personal and private desires, and only respond when provoked (p. 37). This implies that women cannot initiate communication, let alone launch a resistance against the status quo.

<13> In some ways, Guanajuato holds up to the stereotype. The larger state, also Guanajuato, is one of the most staunchly Catholic and conservative states in Mexico, something attested to in the fiercely opposed responses to abortion, homosexuality, and so on, both in the newspapers and in everyday conversation (Lamas and Bissell, 2000; Newcomer, 2002). While the expression “obedezco pero no cumplo / I obey but do not comply” is used occasionally here as in other places to signify the quieter non-compliance with such things as weekly mass, pre-marital sex, and even the prohibition against birth control, it is fair to say that in this small city preoccupied with class and social image, people tend to be less vocal about their deviations from expected practice.

<14> From May to June, 2007, I interviewed an analyst who worked with male and female clients ranging from poor victims of domestic violence to upper class youth at a conservative private school staffed in large part by nuns. When I asked her what she thought the city’s most common psychological problems seemed to be, based on her own cross-section of experiences, she thought for only a moment before replying that in her opinion, the city was most affected by a deep fear of sexuality, male and female. The local culture, she said, is one of taboos. She highlighted the strange nature of how this “taboo culture” works in the city: while physically, everything in the city is seeable and knowable given its unusual shape and small, densely overlapping population, at the same time everything is also hidden and what is not socially acceptable is quickly quieted [1]. How, then, is sexuality managed under these conditions? Exposed as the city is to domestic and international others with their own culturally-formed conceptualizations of sexuality, as well as to globalized media saturated with sexual imagery and to changing attitudes at the national level with respect to the health and legal aspects of sexuality, the city necessarily has to exert effort, whether to maintain or to challenge traditional norms, and as I will show below, foreign languages provide a partial way to do this.

<15> The (Spanish-speaking) city’s foreign language base is modest; it is not a “multilingual city” per se. There is no indigenous language base, but as a university and tourist city, certainly many inhabitants speak or read some other Western languages as a part of their professional lives. There is also intense exposure to U.S media, and tourists are present year-round. Therefore, while officially, multilingual municipal signage is not present in the public sphere, at the unofficial level, one occasionally observes texts in Japanese, English, French and German. Within the middle class and more elite social groups, it is also becoming increasingly common for people to drop English words (much in the way Americans used to do with French) to show their own cosmopolitan-ness: words such as drinks, fancy, nice, coffee break, the academic abstract, and the expression “oh my god,” to mention just a few examples, show up frequently (and sometimes incongruously) in local conversations, even though all of these things can be (and are) expressed in Spanish as well.

<16> While in many places in Mexico, English language texts would simply signal 1) acquiescence to American tourists’ monolingualism; 2) a working through of U.S. relations and cultural and media influences; or 3) a desire to look “modern,” glossed as American, in the case of Guanajuato, I suggest that while all of these conditions hold to different degrees, there is something else at stake. Both English and, in another example I use, French, are employed to communicate something about sexuality and otherness, which produces certain psychic effects. What follows below is a look at how other languages are employed to create sites into which sexuality can be placed and desire expressed.

Bar Names and Bar Flyers—Otherizing Local Space Through Foreign Languages

<17> Following the assertion of the psychologist that sex is the city’s foremost taboo, the expression of desire becomes a transgression that the city otherizes as incompatible with the ideal image she seeks to cultivate. But of course desire persists, so it must be accommodated. The city achieves this by spatializing sexuality in two ways. First, spaces beyond the city limits are deemed as acceptable outlets for transgression. For example, prostitution is relegated beyond Guanajuato’s margins to other nearby cities with highway strip-clubs and brothels which advertise fairly openly. There is also a long string of what are called “autopark” hotels scattered between the multinational businesses and semi-rural remnants of agricultural work that line the highway on the way to León, a large industrial city half an hour from Guanajuato. These hotels, designed for quick trysts, are visible from the road; however, their wide entrances are built to quickly usher in entering cars and then hide them from view, underlining the hotels’ illicit character and protecting the privacy of the transgressor. Tellingly, the vernacular for this stretch of highway is the “Bermuda Triangle,” not because of any triangular shape, but because, as one informant put it, “cars go in and then whoosh, they disappear.” In this space, a rather devouring one, what happens is quickly made invisible, erased from reality.

<18> Officially then, sexuality is shuttled off to the bars, clubs, and hotels of non-city spaces. In Spanish, a husband’s second household with a mistress is referred to as the “casa chica,” the small house that will never challenge the status of the “big house” occupied rightfully by the legal, Church-recognized wife. By displacing sexuality, the city thus conceives of herself always as the “big house,” while these spaces outside the city become the casa chica where transgression is relegated, hidden, and essentially made to disappear. Within the city’s own space, however, zoning sexuality is more difficult. Guanajuato strives to cultivate an image of self as pure, colonial, and tranquil, which is wrapped up in her identity as a colonial-city tourist destination and as a UNESCO patrimony site. Notably, there is no red light district, which is unusual for a tourist destination. Where does in-city desire get transferred? Here is where other languages enter in.

<19> Bar names frequently appear in English, and one also finds bits of English (and occasionally other languages) on the bar flyers posted on public bulletin boards and handed out on the pedestrian streets of the downtown area in the evenings. For example, one bar is named (in English) the “Why not?”. Why not indeed? This name, visible from the street, gives a certain care-to-the-winds attitude to the bar space. Another is called “Whopee” (which means nothing in Spanish), but which has a certain sexual connotation of course [2]. By not translating the bar name, attention is draw to the space’s otherness, and desire is set up because “The foreignness of the language of others generates its own enigmas, speculation, desire to know” (Cronin, 2000, p. 58) [3]. Moreover, place names are not translatable; as proper nouns, they “have a signifier and a referent but no signified,” which suggests that their meanings cannot be transferred (domesticated) into Spanish (ibid, p. 29). This is an interesting proposition that foreshadows the idea that what happens in this other-languaged space cannot be translated into the native-language norm outside…

<20> Moving from the bars themselves to bar flyers, the verbal and visual tactics they employ further otherize these spaces. Rather frequently, bar flyers include images of young foreign women—perhaps as a promise of the forbidden. Sometimes the photos are noticeably asexual, showing tourist-like photos of foreign women sitting in front of local monuments not connected in any way with the bar at hand, creating a rather incongruous separation of the “who” from the “where,” which begins the work to make this space somewhat unreal. At other times, the faces are superimposed onto text about the bar, but again often not linked explicitly (verbally) to whatever is being promoted that night or week. The flyer pictured below, however, proclaims, “Todo el mundo está en el Guanajuato Grill,” which translates doubly as “everyone is at the Guanajuato Grill” and also “the whole world is at the Guanajuato Grill.” While the text is in Spanish (signaling that it is directed to a local audience), the image shows what seem to be a Mexican, an American, and an Asian woman to support its claim.

Figure 1. Everyone is at the Guanajuato Grill

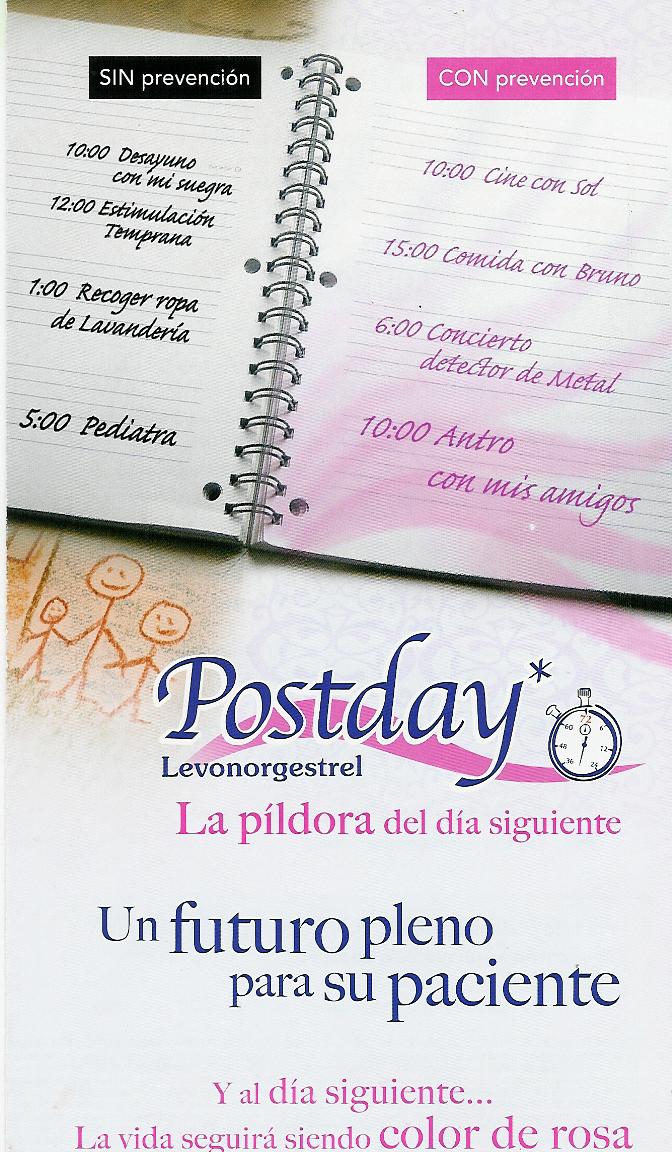

<21> This text effectively brings the world to Guanajuato, and specifically, into this space, which again has an English name (it is referred to as simply “El Grill”). It invites the bar-hopper to step inside a particular locale with a Guanajuato address, but at the same time, it recreates that space as magically cosmopolitan. The space becomes everything that Guanajuato is not: worldly, anonymous, not so intimate.

<22> Another popular bar using an English-language name is the Barfly, a colloquialism connoting a person who spends the bulk of his or her time in this space (rather than in the external spaces promoted by this provincial city in its touristic literature). The Barfly created a flyer from a photograph of a Parisian street sign with arrows pointing in different directions to the Louvre, the Théâtre du Palais Royal, and the Comédie Française, with the bottom sign pointing to its own name, Barfly. The flyer locates the bar linguistically and, albeit through fantasy, geographically as not here, not in this space. The sign transforms the Barfly into an oasis of “away” where sexuality, foreigners, and other taboo things are permitted.

Figure 2. Barfly in Paris?

The whole world is at the Grill, and the Barfly is in Paris…. We see quite a fantasy taking place in the city’s use of other languages on publically posted/distributed texts. Through language, the city brings other sites to Guanajuato and sends local bars to other sites, thus redefining certain city spaces as elsewhere. This cordoning off of space is reiterated through other texts in the city’s public domain as well, as the next section will show.

The Bilingual Text: Desire Respatialized Through Language

<23> Mirroring what happens at the bar level, another set of local texts reinforce this conflation of desire with foreign people and foreign places, again taking things figuratively out of the city. The flyer below is an advertisement for the day-after pill, a hormone-based pill that prevents pregnancy after intercourse has already taken place. In 2006, the day-after pill (la pastilla del día siguiente) was formally approved by the Ministry of Health for inclusion in all states’ basic medicinal supplies that health units should provide. While the day-after pill has been highly controversial in Mexico, in the city, public outcry was especially fervent as conservatives viewed this as both an endorsement of pre-marital sex and an abortive measure (although scientifically, it is not). Nevertheless, the pill is available locally for over-the-counter purchase, and according to one pharmacist I spoke with, both the flyers advertising it and her supply of pills disappear as quickly as they arrive.

Figure 3. Bilingual day-after pill flyer (front)

<24> The front of this text is straightforward. It shows how this day-after pill is packaged around the world (although notably in countries from the global North), with text in both English and Spanish, displaying world flags next to the name of the pill in different countries. The immediate reading is that to take the pill is to be global, to be modern. If the whole world is at the Grill, the whole world now takes the day-after pill, which works to de-stigmatize it. The slogan offers a “pink life” which in its English translation means very little, but in Spanish signifies good, happy, romantized, or otherwise perfect. Through its use of both languages and the images of the flags, the flyer leaps from the local to the global without considering the cultural incompatibilities between traditional Mexican understandings of female sexuality and birth control usage, and the possibilities offered by the pill. Its dual language situation therefore ignores the fact that both the slogan and the pill itself are not easily translated.

<25> A consideration of the flip-side of this advertisement, however, is even more revealing:

Figure 4. Bilingual day-after pill flyer (back)

The text included is displayed in bilingual form, English and Spanish, and as on the front, the English font is larger than the Spanish, despite the fact that we are in Mexico. The flyer offers “important phrases you’ll need to know.” Need? The phrases that follow are pick-up lines in English with the translation in Spanish, and given both the world “beautiful” and the gender-agreement of the Spanish, it is clear that the English is spoken by a man, and the addressee is the woman. This flyer appears to offer the woman a guide to the questions that would lead to a sexual encounter, the after-effects of which would then be counteracted by the day-after pill. Is this possible? Is this an invitation to get accidently pregnant? Even more outlandish is the fact that this flyer is designed as a postcard (to send to whom?); the postcard genre implies that whatever occurs will be sent away, told to someone not here… This particular postcard also includes lined spaces to write down the answers to the pick-up questions, perhaps as practice or rehearsal—What’s your name? my name is X, What are you drinking? I’m drinking a Y, Do you wanna dance? yes I would like to dance. And life will still be rose-colored and perfect because your transgression will be quickly resolved.

<26> It almost appears as if the flyer is intended to train local women how to be picked up at a bar and how to resolve the “accidental” and unplanned sex discussed above. Conveniently, the question “Do you have any birth control?” is left from this list. This omission strongly reinforces the idea that sex is too illicit for female adolescents to plan, even while teaching them how to get into the situations that presumably lead to sex. The message implied about foreigners is clear as well. Women are told that a sexual encounter with a foreigner, whom they will not understand, is acceptable since foreign men do not stay long enough (or speak enough Spanish) to kiss and tell. The text acknowledges women’s sexuality, but still delineates and controls when, where and with whom female sexuality may be expressed [4]. Foreigners thus comply with both modes of permissible sexuality—they are spatialized (not from here but from there) and ephemeral (here only a short time).

<27> The use of English may also perform another function: Cronin notes that other languages are frequently posited in travel accounts as obstacles which delay the satisfying of desire, whether to get somewhere, to achieve a task, etc. (2000, p. 57). The use of a second language can also be seen as a defense, a way to keep things unreal and pretend they did not occur, because the language switch keeps these feelings or experiences at a safe distance (Amati-Mehler et al., 1993). The flâneuse interacts with her potential sexual partner in English, therefore creating desire and relegating the experience to some other space and time. Her approach echoes a common expression used frequently in Spanish to verbally push something under the rug: “no pasó nada / nothing happened.” It signifies that whatever transgression, accident, or injury occurred, has now been erased and forgotten as if, indeed, it had never happened.

<28> At an even deeper level, for the flâneuse, “Leaving the mother tongue is a way of finding another space that is not occupied by the mother, by her language, thus finding an identity that is not that of the mother” (Cronin, 2000, p. 61). By switching to English, the flâneuse thus exits the constructions of sexuality she has been given by (or that she has inferred from) her mother, and by connection, the mother culture. Julia Kristeva has written cogently on how moving into another language constitutes a sort of matricide that is necessary for women to undergo (whether through this route or another), in order to gain full subjectivity separate from the mother (1989, 1995). In Strangers to Ourselves, she observes, “Lacking the reins of the maternal tongue, the foreigner who learns a new language is capable of the most unforeseen audacities when using it” (1991, p. 31); and Stephanie, her main character in Possessions labels her transition from French into the fictional language of Santavarvarian as a process of death, resurrection and rebirth, noting that the new language affects “her senses, organs, and sex” (1998, p. 177). The other-language texts of Guanajuato offer the flâneuse a means to separate from maternal norms and the promise of rebirth as someone new, freed from earlier constraints.

<29> In sum, Agent 223 may use language to pin down the large space of Hong Kong into something intimate, but the flâneuse employs other languages to transcend the local space of Guanajuato and to transform it into something not intimate—something fleeting and faraway. The other language of English on the text allows her to carve out a time (ephemeral) and a space (local but not-local), and by engaging her would-be foreigner partner in English, she signals her own worldliness and break from the maternal space.

The Monolingual Text: Sexuality Further Delimited

<30> Around the same time, another advertisement for this pill appeared in monolingual form. The monolingual text moves us into a different scenario: while the sexual partner in the bilingual text is clearly a foreigner, in the monolingual text below, the sexual partner is a local, which produces a different set of possibilities.

<31> A bit of background is necessary before examining the text: Birth control of any sort is always somewhat controversial in Mexico since the official position of the Church remains firmly against all types except the rhythm method. Young women have commented that bringing their own condoms on dates is poorly viewed; use of synthetic birth control, however, is quite common (about 70% nationally; see Aguayo-Quezada, 2002, p. 96). Tubal ligation after women have given birth to the number of children they wish to have is often performed during the final birth. Married men also get vasectomies, although in the city there are negative cultural associations with this procedure, and many fantastical stories about “vasectomies gone wrong” circulate. Approved of or not, these measures are considered to be strategies employed by married adults who have already had children. For young women, and the oft-ignored category of adult women not interested in having children (married or not), temporary birth control options (e.g. pills, patches, shots) are widely available over-the-counter (without a doctor’s prescription). The flyer below was displayed on a downtown pharmacy counter:

Figure 5. Monolingual day-after pill flyer

<32> This flyer, completely in Spanish (with the exception of the pill’s name, Postday), advertises the somewhat new and daring day-after pill, yet it still maintains a very traditional view of motherhood and marriage. The left-hand column of the datebook (in black-and-white) reminds would-be users that an unplanned pregnancy leads to a day filled with the following activities: breakfast with the mother-in-law, early stimulation (a sort of pre-preschool for babies), domestic errands such picking up laundry, and finally, an appointment with the paediatrician. In short, the day begins and ends with obligations. The implication is that should you have an unplanned baby, your future will necessarily include both marriage and conformity to a traditional role which clearly includes housework, childcare, and the universal issue of trying to please a mother-in-law. Notably, while there is clearly a husband involved in that there is the presence of the mother-in-law, there is no sign that the husband might be a partner in any of these duties. Nor is there any opening for career or school. Most visible (by its invisibility) is that there is also no room for single motherhood as a viable option. In short, there is nothing going on here that even remotely challenges the traditional model of pregnancy=marriage and conformity to rote gender roles.

<33> In the right-hand, pink column is the hypothetical schedule of the young woman who does take this pill. Her day begins with a cinema date with one man, progresses to lunch with another, moving on to an evening concert to see a group called “Metal Detector,” and finally, a night at the bar with friends. There is no obvious reference to the relationship that led to the pregnancy: this man is potentially forgotten and erased into the past. No mention is made, again, of school or career (the relevance of which will be taken up below). And the slogans on this side of the brochure are in pink, reinforcing the pink messages on the lower half: “The day-after pill. A full future for your patient. And the next day… life will still be rose-colored.” Within the flyer and on the back cover (not pictured), the fact that the pill is not abortive is stressed several times (“Por esto podemos asegurar que Postday* La píldora del día siguiente no es un método abortivo.”)

<34> The monolingual text communicates several things. First, it is marketed directly and exclusively to adolescent women, since a single older woman would presumably be working and less likely to plan cinema outings at 10 a.m., or heading to what sounds like a heavy metal concert. Beneath this marketing decision is also the unspoken assumption that women beyond adolescence would not find themselves in the situation of the needing the day-after pill, much less desiring it. The text suggests that women beyond adolescence either would not have spontaneous, unprotected sex, or that older women who find themselves unexpectedly pregnant would never consider recurring to the pill, prompting one to question if they would simply get married. Married women, who also find themselves accidentally pregnant on a regular basis, especially if they are complying with the Church injunction against birth control, are certainly not addressed in this text either. Our flâneuse, then, is further defined as being in a young age group.

<35> By setting up the pink column as a list of purely fun items, the text defines (and strives to prolong) adolescence as a period of sexual freedom. With no school and career references, the text creates an image of adolescent womanhood as simply being a free moment before the demands of traditional adult womanhood (wife and mother), no matter which side of the pamphlet the adolescent falls on, which reinforces the idea that this is a brief and particular phase of life. The lack of emphasis on thinking and preparing for the future is furthered by the fact that the brochure does not openly (on the cover) encourage adolescents to perhaps plan for future birth control needs. Sex, which in this scenario has led to a pregnancy, is represented as unplanned and accidental which serves to de-normalize it: the cinema and the bar are scheduled into the datebook, but sex is relegated to being a surprise and an aberration, even as unplanned pregnancies are expected enough for a company to manufacture day-after contraception.

<36> The Postday pill thus provides an option that simultaneously forecloses other options and keeps things inscribed neatly into the acceptable order. The same traditional schism of good-woman/bad-woman (virginal/sexual) is now reconfigured as a tightly-confined choice between good-traditional and good-modern [5]. As a teenager you may aspire to the “rose-colored life” of fun social outings and multiple relationships, but if you end up pregnant, your only option is to erase the fact quickly or to fit back into the traditional mode, which pre-configures a “return” idea I will take up below. It also subtly reminds women that they may “sow their oats” in adolescence; but they may not do such things as adults, or much less, as a woman with a child. This corroborates Kristeva’s understandings about the construction of maternity in terms that are incompatible with sexuality and pleasure. A woman “will not be able to accede to the complexity of being divided,” she writes in “Stabat Mater,” always having to choose between maternal or “fallen” (1987, p. 248), even as here in the text, “fallen” is now okay under certain circumstances.

Projective Identification and a Return to the Norm

<37> Analyst Thomas Ogden (2005) describes three stages necessary for a successful experience of projective identification. First is the displacement of the unwanted part of self that threatens. This part is ejected into a proximate space, projected into someone/something with whom there will be interaction, so that this unwanted object or part is not lost forever. As this article has attempted to show thus far, the city projects “disowned aspects of self” (Grant and Crawley, 2002, p.18), her own taboo desire, into spaces (fantasized as other), into interactions in another language (making situations less real), and into foreigners themselves (who are passing through and play a specific role that locals cannot).

<38> From their clinical observations of female, multilingual patients, Amati-Mehler et al. conclude:

It seems to us that by substituting the language of their childhood with a new language—the conveyor of new thought and affect routes—and by adopting a cultural and emotional context not mortgaged by the archaic conflicts, they not only rendered a service to resistances and defenses, but they also created new passages that provided them, albeit at the cost of deep and painful splitting, with valid and structured introjections on which to reorganize their adult feminine identity. (1993, p. 71)

The flâneuse does not travel physically to another site, but she does travel to the fantasized foreign context of the otherized bar and the other language of the pill texts, thus opening the “new passages” referred to above, and experiencing the splitting as well. The bad or taboo part of her, her desire, is separated from her usual Spanish-speaking, rest-of-the-city self. And the city echoes this splitting by spatializing sexuality into separate, othered spaces both in and beyond her borders. These spaces “not mortgaged by archaic conflicts” thus open a possibility and keep desire near enough so as not to lose it completely.

<39> Second, the recipient person or object is pressured to experience his own self in such a way that corresponds with the projected fantasy. Projective identification is a two-way street as it is the recipient’s behavior or thoughts that allow the projector to control the projected feelings or aspects and reassure herself that they are not gone forever. In this case, the local space permits the projection—the bars see and promote themselves as transgressive spaces, and they produce flyers that reiterate the otherness of desire, using foreign language as one way to do so. This allows the city to control space and to maintain her ideal, pure self which is then opposed to other spaces understood as decidedly less pure. For the adolescent flâneuse as well, her acquiescence to the postcard fantasy interaction with a foreigner, undertaken in English, also shows how these created spaces “work.” She is not propositioning her would-be partner in Spanish, but in English; she is temporarily other to her own self as she does this.

<40> And foreigners, although this is said more symbolically and should not be overstated, play a return role here: they accept the construction of themselves as passing, ephemeral, fun, liberal…even if they do not necessarily see themselves as such at home. As Kristeva observes, the foreigner frequently enters into a libertine state, released from his or her own repressive societies. She writes: “foreigners continue to be those for whom sexual taboos are most easily disregarded, along with linguistic and familial shackles,” and she notes that it is the foreigner who “causes scandalous excesses in the host country” (1991, p. 30). But she also points out that the foreigner’s words in the new language

are centered in a void, dissociated from both body and passions, left hostage to the maternal tongue. In that sense, the foreigner does not know what he is saying,…the foreigner can utter all sorts of indecencies…since his unconscious shelters itself on the side of the border. (p. 32)

Even the foreigner’s seemingly easy escape from repression may not last.

<41> This brings us to the third step of a more healthy projective identification process. Projective identification can only mark a “pathway for psychological change” if the feelings are reinternalized in some modified form made possible during the other person or object’s containing of them (Ogden, 2005, p. 21). For the projecting city, this could happen if the bar sites performed a different understanding of sexuality that would enable the city to re-understand desire as a now acceptable aspect of the self. Or it could happen if the monolingual text allowed for a non-traditional choice instead of reinscribing the consequences of an unplanned pregnancy back into the status quo. Or finally, it could happen if the flâneuse could link the freedom available in the other-space of the bar and in the otherness of her interaction with the hypothetical foreign sexual partner into a protest against the conservative norms of the city.

<42> But this does not occur—what happens in adolescence, in the bar, or out of town, remains contained in those specific time-spaces. While the different language moves cited here attempted to open up change, the monolingual pill text reproduces the impossibly split woman, since it so clearly forecloses sexual desire/pleasure for the woman who becomes a mother. This means that the moment of opening for the adolescent flâneuse is transitory and not linked forward to a challenge of existing norms and prohibitions. Following Melanie Klein (Kristeva, 2004; 2007), one could also view this as a sign of an immature city subject splitting her desire into good object, bad object.

<43> If adolescents are allowed some sexual leeway, and if illicit sex is tolerated in the spaces noted in this article, why do these temporary rebels return and reproduce the norm (in appearance if not always in action) as adults? To some extent of course, adolescence in many places could be seen as a swerve slightly beyond and then back to an eventual adult norm, but the Guanajuato case seems extreme. Two psychologists commented that a common saying directed at daughters when prohibiting something is “Para que no te pase lo que a mí me pasó/So that what happened to me doesn’t happen to you,” a saying that connotes heavy guilt and often, regret. Freud states:

The pleasure of the impulse constantly undergoes displacement in order to escape the locking which it encounters and seeks to acquire surrogates for the forbidden in the form of substitutive objects and actions. For the same reason the prohibition also wanders and spreads to the new aims of the proscribed impulse. Every new advance of the repressed libido is answered by the prohibition with a new severity. (1918, p. 51)

The impulse towards what is prohibited does appear to be met again by a re-fortified prohibition, even if it is self-generated. We see a tightening rather than a loosening of norms over generations even in the midst of social change and new experiences with outsiders.

<44> That said, it would be remiss not to emphasize that as in other sites, a critical element at play in the city has been the failure of the feminist revolution. As one local psychologist lamented, important feminist advances were made in the work world and in the policy arena; however, the “revolution was never fully realized in the household,” which subsequently produced shame on the part of those who had attempted to move outside the traditional, conscripted models of femininity. This echoes a spatial metaphor: it is commonly said that the sexual revolution occurred “de la puerta hacia afuera/from the door outward,” meaning that despite changes in the outside world, nothing changed in the intimacy of the domestic world behind closed doors and within gender relationships. In Guanajuato, we see this clearly: outside the city, the expression of desire and sexuality is accepted. In these pockets of other local spaces remade as “not here,” desire finds a place as well. But in the “real” space of the city which surrounds the bar sites, the revolution is not invited in.

<45> The Hong Kong flâneur cannot break multilingual space down into the monolingual community he fantasizes about; therefore, he cannot find the nostalgic, lost maternal symbolized by this space. In Guanajuato, our flâneuse with her other languages cannot open up space permanently to otherness and thus separate from the maternal symbolized by her local space. Once the flâneuse leaves the world at the Grill, or steps out of Barfly’s Paris to return to the streets of Guanajuato, things right themselves back into the separate spheres of transgression-elsewhere/conformity-daily reality and adolescence/adulthood. The city of Guanajuato fails to complete the projective identification process successfully. With no bridging of transgressive space to everyday life space, no change is possible. What we see here remains a defense.

Conclusions

<46> Mexico City anthropologist Néstor García Canclini (1995) maintains:

The meaning of the city is constituted by what the city gives and what it does not give, by what the subjects can do with their lives in the middle of the factors that determine their habitat, and by what they imagine about themselves and about others in order to "suture" the flaws, the absences, and the disappointments with which the urban structures and interactions respond to their needs and desires. (p. 751)

In different ways, both the Guanajuato flâneuse and the Hong Kong flâneur of Chungking Express use other languages to suture the flaws, albeit to opposite ends. One uses language (English and French) to search out a more anonymous, open, global space within a sometimes suffocating local site that constructs sexuality as taboo. The other uses language (Cantonese, Japanese, Mandarin Chinese, and English; Huang, 2004, p. 38) to locate a more intimate community-like space within the anonymous mega-city that appears to make romance and belonging unattainable. Notably, both are also suturing over their own subjective struggles between the ideal self who would be “at home” in the city where they live, and the more problematic, desirous self, not at all convinced that things are okay as they are. The affective needs that are not met by the city must then be sutured over, even if such suturing is only temporarily effective, if at all.

<47> The complex desires and fantasies that result intersect with language and with questions of global flows and mobilities, respectively. Multilingual landscapes in any city are both discursively and materially constructed. In Chungking Express, several texts flash at us in neon or on light boxes, and they are globally branded; more prominent in the film, however, are the bits of foreign language that punctuate the landscape of speech. In Guanajuato, by contrast, the bar texts discussed here are produced on home computers and circulated only briefly before being replaced, and the flâneuse’s own foray into foreign language use is textually catalyzed by the day-after pill postcard. Strikingly different, both of these multilingual environments simultaneously offer opportunities to connect with and disconnect from the city. The neon signs and pieces of spoken language seem to offer a sense of place (one is in the global city of Hong Kong; many people speak the many languages at hand), even as they disconnect the viewer from any sense of locality as the materials and discourse are portrayed as overly “place un-specific” (for example, one scene features a McDonald’s sign; many global cities would include multilingual inhabitants). In contrast, for the Guanajuato flâneuse, local bar texts are exaggeratedly local, often lacking dates (“live music tonight”) and street-less addresses (“at the Barfly”) as this knowledge is assumed. They are irreversibly linked to the local even as they recreate city spaces as global, elsewhere, and other. The paradoxes embedded in both situations must be negotiated.

<48> The Guanajuato case also provides insight into how global flows and mobilities play out in a small city. Bits of language flow in, as do foreigners, but not always together—the tourist does not necessarily bring in the language evidenced on the flyers here, nor does he account for the random words that drop into daily use from seemingly nowhere. These disjointed flows of bodies and verbiage intersect and overlap with information mobilities, pharmaceutical flows, and even movements of desire. Within the resulting assemblage of goods, languages, cultural values, deviations and conformities to norms, one element cannot be separated one from the other: we can only examine how certain individuals or groups might experience these different flows and mobilities in a given time and place. In all cases, the body becomes a vehicle through which both a sense of place and a sense of all this movement is experienced (Sheller and Urry, 2006). And the flâneuse becomes a convergence point, an utterance among myriad speaking subjects, all negotiating how to live in the mix of global and local. Herein are exposed the psychic constraints of affective mobilities: the fantasy-traveler flâneuse leaves only to enact a return when she moves back into normalized space—not a return of the repressed, but a return to the repressed status quo.

<49> As globalization extends beyond the megalopolis, traditionally monolingual cities are experiencing the incursion of other languages, which shows up not only in those speaking other languages, but also, increasingly, in the myriad multilingual texts that show up on even small city linguistic landscapes. The affective meanings of these untranslated and resolutely Other pieces of language will only make sense within the cultural and historical context of each city, but they will tell us much about how different places make sense of otherness and what cities and residents do with the psychic possibilities afforded by foreign languages.

*The author wishes to thank geographer Dr. Bradley Rink of Cape Town, South Africa, for his insightful comments, as well as Dr. Angela Flury for her suggestions and careful editing.

Notes

[1] Note that not every psychologist I spoke with during this research identified sexuality as the most prominent problem of the city; for example, one underlined the split from Spain, and another kept referring back to the effects of economic hardship. All, however, were quick to link repression and sexuality with both the dynamics of local social life as well as the topographical specifics that permits easy vision of what occurs in the city.

[2] It is not within the scope of this paper to discuss the homosexual flâneur or flâneuse; however, it is worth noting that homosexuality is even more taboo than straight sexuality in Guanajuato. While there is no openly “gay bar” in town, the “Whopee” bar is rumored to be one of the sexually most permissible sites. It is notable that this bar, then, with its English name, becomes the gay option.

[3] In everyday slang, young people also use the expression “un free” to signify a quick sexual relationship that doesn’t count or hold any commitment, suggesting a “free pass” perhaps. Again, the English otherizes the experience; there is no easy Spanish equivalent.

[4] This maps onto a generation of local stories about foreigners serving as temporary sources of romantic and sexual attention, stories that are wrapped up in changing gender norms as well. The way these stories are told, in the previous generation local women resented the arrival of more liberal foreign women who would take away the potential boyfriends. Now, both sexes manipulate the arrival of tourists as opportunities for more liberal, yet discrete, ephemeral relationships.

[5] In practice, single motherhood is now quite accepted by women’s parents as a better alternative than an unhappy marriage, and women do often continue with schooling/work. The text is notable precisely because it repeats such traditional norms.

Works Cited

Amati-Mehler, J., Argentieri, S. and Canestri, J. (1993). The Babel of the Unconscious: Mother Tongue and Foreign Languages in the Psychoanalytic Dimension. Translated by Jill Whitelaw-Cucco. Madison, Connecticut: International Universities Press.

Aguayo-Quezada, S. (2002). México en Cifras. Mexico City: Hechos Confiables S.A. de C.V. and Editorial Grijalba.

Ben-Rafael, E. et al. (2006). Linguistic Landscape as Symbolic Construction of the Public Space: The Case of Israel. International Journal of Multilingualism 3(1), 7-30.

Ben-Rafael, E. (2009). in E. Shohamy and D. Gorter (eds). Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery. New York, Oxon UK: Routledge.

Cronin, M. (2000). Across the Lines. Travel. Language. Translation. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press.

Fray, H. (2001). “La Malinche y el desorden amoroso novohispano.” In M. Glantz (coord.) La Malinche, sus padres y sus hijos. Mexico City: Taurus, 251-256.

Freud, S. (1918) Totem and Taboo. (Orig. New York: A. A. Brill, 1918). BiblioLife. Available at: http://books.google.com/books?id=7P9KJuAXGHUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Totem+and+Taboo&ei=YlGBSpaAMpqGkgSV2oirCg#v=onepage&q&f=false

García Canclini, N. (1995). “Mexico: Cultural Globalization in a Disintegrating City,” American Ethnologist, Vol. 22 (4), 743-755.

Grant, J. and J. Crawley (2002). Transference and Projection: Mirrors to the Self. Buckingham, Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Gutmann, M. (1996). The Meanings of Macho: Being a Man in Mexico City. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Huang, T. M. (2004). Chungking Express: Walking with a Map of Desire in the Mirage of the Global City. Walking Between Slums and Skyscrapers: Illusions of Open Space in Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Shanghai. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 31-47.

Kristeva, J. (1989). Black Sun: Depression and Melancholy. Translated by Leon Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press.

---. (1991). Strangers to Ourselves. Translated by Leon Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press.

---. (1995). “Bulgarie, ma souffrance,” L'Infini, No. 51 1995, 42-52. Available at: <http://www.kristeva.fr/bulgarie.html >

---. (1998). Possessions. A Novel. Translated by Barbara Bray. New York: Columbia University Press.

---. (2004). Melanie Klein. Translated by Ross Guberman. New York: Columbia University Press.

---. (2007). Adolescence, a Syndrome of Identity. The Psychoanalytic Review, 94, 715-725. Available at <http://www.kristeva.fr/adolescence.html>

Lamas, M. and Bissell, S. (2000). “Abortion and Politics in Mexico: ‘Context is All,’” Reproductive Health Matters, Vol. 8 (16), 10-23.

Newcomer, D. (2002). The Symbolic Battleground: The Culture of Modernization in 1940s León, Guanajuato. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 18(1), 61-100.

Ogden, T. (2005). Projective Identification and Psychotherapeutic Technique. London: Karnac.

Paz, O. [1950] (1961). The Labyrinth of Solitude. Translated by Lysander Kemp. New York and London: Grove Press and Evergreen Books, Ltd.

Pennycook, A. (2010). Language as Local Practice. London: Routledge.

Ramírez, S. (1977). El mexicano, psicología de sus motivaciones (1977). Mexico City: Grijalbo.

Ramos, S. (1934). El perfil del hombre y la cultura en México. Mexico City: Colección Austral.

Uranga, E. (1952) Análisis del ser mexicano. Mexico City: Porrúa y Obregón.

Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment & Planning A. 38(2), 207-226.

Shohamy, E. and D. Gorter (eds) (2009). Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery. New York, Oxon UK: Routledge.

Return to Top»