Reconstruction Vol. 12, No. 2

Return to Contents»

Minecraft, It’s a Mod, Mod, Modder’s World: Computer Game Modifications as Civic Discourse / Beth Beggs

Abstract: This paper views computer game modifications as acts of commentary among communities of game players and fans. Many of the most popular computer games contain an End User License Agreement ( EULA) intended to protect corporate interests by maintaining the producer/consumer binary. Thus, modders must choose to play games that prohibit them from using their creativity and skills or migrate toward that encourage modding. Large and growing numbers of players-turned modders are creating and distributing skins, textures, environments, and back stories that increase player satisfaction and extend player interest. Through this civic discourse, modders use the gaming industry’s EULAs to upturn the producer/consumer binary and redistribute corporate power among the masses.

Keywords: modding, Minecraft, computer games, modification, EULA

<1> My daughter returned from her first quarter at college with a story about her friends playing a game of Mario Kart. At the time, I had never heard the term modder, but by the end of her story, I was intrigued by the type of play she described. First, a mystery player demonstrated resistance to the most basic elements of traditional game-play—“Follow the rules and wait for your turn.” At the same time, the player caused no real harm and appeared intelligent, witty, and downright playful. The girls’ avatars were racing their carts, when a new character suddenly tossed banana peels onto the track. Carts slowed down and spun out. The player who had been in first place quickly lost her lead as other carts blew past; then, another bunch of banana peels landed on the course. Again, carts slowed and spun. Angry that a player had joined their race and manipulated their ability to compete, these girls were surprised when the uninvited guest finally allowed the race to continue—but without his avatar and cart. This player, whose skills allowed him to control their game, finished last—without accumulating significant points or prizes. My daughter and her friends were amazed that a player who could control their play would stand aside and intentionally lose the game (Beggs).

<2> After describing this race to a friend who enjoys the independently released computer game Minecraft, I realized that the generous player from my daughter’s game was not unique (King). While my daughter originally identified her unknown player as a hacker, as we discussed the event further, she decided that he was really a modder because he altered elements of the game through his possession of an unlimited supply of banana peels. In one moment, the modder was simply observing the race without taking points; the next moment he was slowing the other racers. This player demonstrated the power to win the game and control the finishing order of all other players. My friend pointed out that modders demonstrate an interesting oscillation between cultural resistance and a desire for acceptance, between creative independence and the need to belong within the gaming culture and greater society. In short, modders’ behavior disrupts the traditional binary of either resistance or acceptance by simultaneously embracing and rejecting gaming cultures, mainstream US culture, the gaming industry, and the rules and limitations of the game as originally designed.

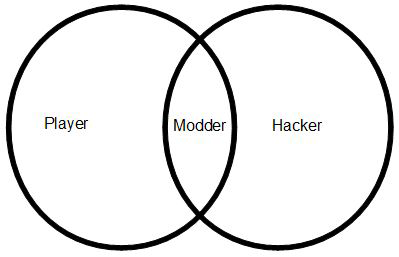

<3> The terms game-playing, -hacking, and –modding are defined by sometimes subtle distinctions. Further more, these tree terms remain contentious both within and without gaming culture.

|

Figure 1 |

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the first printed appearance of the term gamer to a 1981 issue of White Dwarf Magazine where it was used to describe “a participant in a war-game or role-playing game; a player or creator of such games” (OED).

<4> Media often portrays the game-pl as a lone-wolf male, a ten or twenty-something hiding in a darkened room playing a game that allows him to virtually experience high levels of violence and sexuality. In reality, gamers are a little bit over 20, and they are almost as likely to be female as male. According to the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), 53% of U.S. gamers are between age 18 and 49; players under 18 constitute only 18% of all U. S. gamers, and the remaining 29% are over age 50. Most of U.S. gamers are male, but nearly half—42%—are female (ESRB). 72% of U. S. households contain at least one gaming member, and current research indicates that gamers and modders are generally productive and creative citizens within the real world and their virtual world of choice (ESRB). Finally, a full third of the respondents to the ESRB survey identify playing computer games as their favorite form of entertainment—over watching television or movies, listening to music, and hanging out with friends (ESRB). This tells us that U.S. gamers constitute an almost evenly divided male/female group, approaching or solidly within middle-age. Furthermore, these self-identified gamers are committed to this form of entertainment above others.

<5> In “Computer Network Abuse,” Michael P. Dierks explains that “the term ‘computer hacker’ is now synonymous with computer criminal and carries strong negative connotations” (Dierks). The origins of the term, however, are quite different: “The word ‘hacker,’ when it was applied to technology, initially meant college students and hobbyists exploring machines. At worst, a hacker was a prankster” (Kushner 25). David Kushner in “Machine Politics,” noted that “over time, ‘hacker’ acquired a more sinister meaning: someone who steals your credit cards or crashes the electronic grid. Today, there are two main types of hackers, and only one causing this kind of trouble” (Kushner 25). Commonly referred to as either “white hat” or “black hat,” “a ‘white hat’ hacker might be an antivirus programmer, for instance, or someone employed in military cyber defense—aims to make computers work better. It is the ‘black hat’ hacker who sets out to attack, causing havoc or ripping people off” (Kushner 25).

<6> In the early days of computing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the term hack was first used by members of the MIT model railroad club to refer to, “a project undertaken or a product built not solely to fulfill some constructive goal, but with some wild pleasure taken in mere involvement” (Dierks 310). As Dierks explains, hacker remains a slippery term. A key quality distinguishing hackers from modders is intent. Although both hackers and modders may share a curious nature and similar skill sets, current-day hackers are most often known for mischievous or malicious actions, and a common hacking goal is to exploit weak computer security.

<7> Particularly within the context of computer game play, the terms hacker and modder may be confusing. Modders, on the other hand, frequently demonstrate benevolence and civic awareness by designing and sharing productive game modifications that harmlessly enhance play. Modders, sometimes considered game co-creators, have only recently become accepted as a mainstay of gaming culture. Although media presents modding as the newest gaming trend, modifications to games and play are not a new practice: “Throughout history, gamers have created new variations of games by altering the existing rule systems” (Sotamaa). Families frequently play by house rules and card games often rely on the dealer’s choice. While these generally accepted game modifications traditionally rely upon oral communication, the virtual playing field of computer games requires players to seek alternative modes of communication. Because players may live in different time zones and even on different continents, they often write out their discoveries and modifications in game forums or on fan sites before or even instead of verbalizing them (Planet Minecraft). Matthew Johnson in “Public Writing in Game Spaces” comments on the degree of literary productivity he observes within the gaming community and beyond:

“Gamers, motivated by seemingly simple 'play,' participate in an enormous number of writing activities, creating a diverse body of texts: gamer-authors write online journals (from both player-characters' and gamers' perspectives), strategy guides, walkthroughs, fan fiction, and blogs” (Johnson 271).

These players are actively and purposefully forging a community and using writing to enhance the virtual and real world lives of other like-minded players.

<8> In general, computer game players—gamers—have typically been socially marginalized (Kücklich). Despite this marginalization, Minecraft players and modders, are quite devoted and particularly successful in creating strong online communities and fan-based groups. For instance, there are currently 26,768,577 registered Minecraft users. Of that number, almost 65,000 new players registered. In fact, Minecraft is so popular that nearly 21% or 5,614,658 players chose to purchase the newest version rather than continue to play the older free version. Of those more than five million purchasing gamers, 8,459 purchased between April 18 and 19, 2012, alone (“Statistics”). This means that Minecraft players have both metaphorically and literally invested in their community.

<9> Minecraft, a creative building game invites players to design and create a world by selecting Survival, Hard Core, or Creative mode. Players enter a world where everything is made of cubes called blocks. In Survival or Hard Core mode, players must quickly build a secure shelter for the night or risk annihilation by zombies. Players create these shelters by chopping trees to create blocks of wood and stacking the blocks to form a house or by digging a cave-like hole. More knowledgeable players collect basic supplies like chopped wood and buried coal to create hatchets and other tools as advanced as steam engines. Creative mode, however, provides players with unlimited basic supplies like wood, bricks, glass, water, wools, and food, but players must create their own tools.

<10> Furthermore, the more than 26 million Minecraft players are scattered across the globe; but through their shared enjoyment of the game, they create communities: a real-world community of Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game (MMORPG) players, a virtual community of Minecraft players, and sometimes a community of miners and builders within the game. As members of a community, Minecraft players communicate and self-govern just like members of real world communities, and just like real world communities, they demonstrate resistance through civic discourse.

<11> The large community of Minecraft fans collaborates to provide playing and modding support. Because Minecraft was originally designed as a low-budget independent release, the official Minecraft site did not intend to provide the same level of technical support as well-financed releases by major companies. In response to the dual needs for community and assistance, the site hosts forums where the fans support and encourage each other. Joining the official Minecraft site, the fan-created Planet Minecraft site hosts a variety of forums. At Planet Minecraft, players and modders find advice for working through in-game problems, tips that enhance play, and directions for creating and using thousands of free game mods.

<12> Modders, obviously, enjoy playing their favorite game; however, their game play often tests the line between acceptance of the game’s official rules and resistance to them. For example, a gamer who frequently plays her favorite game may demonstrate her desire for acceptance by playing the multi-player version of the game or by posting comings to a forum. She might also show her acceptance of the prescribed rules by using the tools exactly as they were originally designed. Alternatively, the same player who enters a multiplayer environment may choose to disrupt her own play an the play of others by resisting the rules. The most obvious way to resist rules is to violate them. However, a more creative form of resistance employed by many modders actually moves the realm of play beyond the rules’ parameters. Rather than violating the stated rules rules, Minecraft modders frequently extend play beyond the reach of rules by creating new worlds and objects or by altering the appearance and behaviors of existing objects and elements like avatars or water.

<13> As consumers, modders are unimportant contributors to the gaming industry; however, mods often violate more than just official rules. Mods, by definition, resist most copyright laws governing access to the game’s structure, environment, and avatars (“Terms of Use”). In the most interesting example of both resistance and acceptance, Minecraft modders destabilize the corporate balance between consumer and producer while they infuse the game with new material expanding gamer interest. Thus, even their acts of resistance produce the effect of support for Minecraft developers by providing an endless supply of free game-extending mods.

<14> Furthermore, the Minecraft community’s desire for community engagement through shared information and experiences reveals a significant difference between game corporations and game modders: while the game-producing industry seeks to profit from fan play, modders are often satisfied with a demonstration of appreciation for their benevolence. One modder using the handle “Ihack@you” explains this philosophy in a forum post: “While I personally do not care about my VR [Virtual Reality] score . . . I understand some people do so I will not stick around and have you lose points race after ace”(Ihack@you qtd. In Postigo). Ihack@you claims that his VR play is pure—for enjoyment of the game, but he recognizes that some players care very much about earning game points. In consideration of those players, when he uses a modification to enter others’ game play, he exits before causing destruction or players to lose points. Like other community-building activities, Ihack@you’s actions become a form of civic discourse.

<15> Johnson describes a contemporary form of civic discourse that is at its most basic level, is a public conversation about public concerns. For instance, the forum posting by Ihack@you is an open and public discussion of his beliefs concerning hackers and modders who cheat during multiplayer game play. This topic, pertinent to anyone playing a MMORPG, initiates a public dialogue among concerned members—gamers—of both a very specific gaming community—Minecraft players, for instance—and the gaming community at large.

<16> Since the original 2009 release of Minecraft, modders’ communal and democratic ideals have become more pronounced. While many early modifications were only intended to enhance personal play, current modders often design and share projects of greater social utility. For instance, modders’ projects are often publicized and shared among other modders and players; thus, they use their work to help others further their enjoyment of the game. Minecraft modders design mods and in-game projects that accomplish this goal by creating witty or culturally significant character skins. Others design complex structures for protection or amusement. The common factor among Minecraft modders is that they freely share their discoveries with other Minecraft fans. This behavior exemplifies Minecraft modders’ strong desire for acceptance within a community, even as they resist the larger game industry community, the mainstream community and even the non-modding gamer community. For instance, Eric Fullerton’s YouTube video “In Search of Diamonds” provides a walkthrough of the Minecraft community, and as such, it is an example of social commentary. At the same time, Fullerton’s video is a creative work of digital art.

<17> “In Search of Diamonds,” Fullerton’s bearded avatar narrates the tour of every-day life in the creative building virtual world of Minecraft (“Diamonds”). The tour’s musical soundtrack was composed, played, sung, and recorded by Fullerton, and this level of creativity is an example of the playful, multiple texts created by modders. “Diamonds” presents the game as an eternally incomplete text constantly undergoing revision. As designed by Mojang, Minecraft is a very basic text with no back story; however, unlike other more complex computer game texts, Minecraft encourages a very high level of creative play. While other popular games allow creativity within defined and defended parameters, Mojang invites its players to redesign the playing field in both minor and extreme ways. By hosting a modding forum at the official Minecraft site, players gain access to the game’s coding as well as thousands of modifications designed and published by other player-fans-turned-modders. Therefore, Minecraft modders, as members of the larger gaming community, are simultaneously resistant to and marginalized from mainstream communities. Also, Minecraft modders, like the game’s parent company Mojang, both belong to the Minecraft playing community and resist that community by redefining the playing field and the act of play within the Minecraft world. Ultimately, the very act of creating a game modification becomes an act of civil disobedience, an act of civil discourse, an act of rhetoric, or the initiation of a conversation—“Let’s play!”

<18> The level of creativity in Fullerton’s video demonstrates his varied communication skills and his adaptability within multiple modes of discourse—as director, writer, composer/lyricist, instrumentalist, and vocalist. Like the multi-talented Fullerton, modders are often skilled rhetoricians capable of effective communication in multiple forms of traditional and multi-modal media. As socially aware citizens, the modders/rhetors exhibit community building through shared interests and experiences.

<19> This rhetorical tradition traces as far back as 338 B.C. to the ancient orator and teacher Isocrates, who describes the successful rhetor as, “great and honorable, devoted to the welfare of the humanity and the common good,” also noting that,

“It follows, then, that the power to speak well and think right will reward the person who approaches the art of discourse with love of wisdom and love of honor” (Isocrates).

Later, around the year 100, Quintilian explained that successful rhetors must first become good men. This “includes all the virtues of oratory and the character of the orator as well, since no man can speak well who is not good himself” (Quintilian). Following Quintilian’s assertion that an effective speaker must foremost be an individual of outstanding character, Johnson explains that, “[T]he gaming itself that takes place in [MMORPGs]...serves as a model of active, civic participation” (Johnson 274). Even as gamers’ gaming interests may result in their real-world marginalization, these acts of gaming and modding define the players as real leaders in the virtual world: “In essence, the textual production gamers engage in is a form of public writing that influences, shapes, and affects the larger community—not just an immediate group of gamers” (Johnson 274). These public texts about community issues effectively change, or revise the game’s universe as well as the gamers’ playing decisions.

<20> An excellent example of gaming civic discourse appears in a Minecraft modding forum. A new modder shared his first mod—a very useful script that helped miners dig through bedrock. When a more experienced member posted that there were already hundreds of existing mods performing exactly the same function, the community quickly responded in defense of the less-experienced modder. Their comments publicly reprimanded and marginalized the more experienced modder, while they protected a vulnerable member. Thus, the community responded to this situation by reminding members of their shared beliefs and punishing the violator. The community of Minecraft modders created a collaboratively composed document through the forum posts, that both articulated and enforced civil obedience (“Forum”).

In Johnson’s article about gamers and public writing, he explains that “[T]he writing computer gamers do in and for their online communities is not only directed to clearly definable audiences and with specific purposes, but it also has the potential to institute real, measurable change within gaming communities and the larger gaming industry. What is more, the playspace in which gamers write is comprised of textual exchange that is self-motivated; the writers themselves collaboratively construct them” (Johnson 270).

The Minecraft modder forum demonstrates the supremacy of civic discourse described by Johnson. The community’s unified, public disapproval of an abusive member’s post established a consequence for violating rules. The Minecraft modder forum participants’ demonstration of disappointment, thus, positions the modders as authors of social reform. Similarly, modders are altering the game industry. Some game designers have begun hiring modders, but others are reinforcing their security to prevent modders from accessing their proprietary code.

<21> Johnson stops short of making the connection between the ancient art and discipline of rhetoric and today’s gamer-authors, but the comparison is valid. Rhetors Isocratese and Quintilian describe the successful speaker as one who must, first, be civic-minded, and Ralph Waldo Emerson also dismissed the significance of the orator’s actual words focusing, instead, upon his actions. Emerson writes, “His speech is not to be distinguished from action. It is the electricity of action. It is action.” Just as Emerson’s orator/hero descends from the ancients, so do Minecraft’s game-author/modders. Both their discourse and their actions serve to uplift the community.

<22> Kathy Sanford and Leanna Madill observe that “Popular culture and media have historically been used as sites of resistance, whether through music, banners, graffiti, or alternative newspapers. . . . Game players demonstrate many examples of resistance through challenges to rules and structures imposed by existing society.” (Sanford and Madill 293). In Minecraft, modifications resist and refigure the structure, but this behavior is, in fact, in accordance with the game’s rules and ethos which encourage building and creativity. In addition to public writing and causing social change within the game, players and modders demonstrate high levels of creativity. Kimberly Lau, in “The Political Lives of Avatars” notes that ”when players create their avatars in WoW, they have choices, but those choices are restricted to a limited number of facial features, skin tones, body types, and hair types, textures, and styles,” (Lau 374-5). Because WoW forbids and attempts to prevent all player modifications, players must configure avatars within the game’s parameters. Therefore, WoW players will likely meet another avatar with the same facial features, skin tone, body type, and hair as their own. These boundaries diminish the level of creative opportunities. In fact, “Avatars are virtual selves. They represent the complex processes and ongoing practices involved in constituting ourselves in virtual worlds” (Lau 381). Not only is gamer creativity challenged to imagine and construct their avatar in a virtual world, but players are then limited in the range of creativity allowed. This mixed message: encouraging creativity while restricting it, is yet another reason that modders might view their mods as both necessary and harmless.

<23> Through shared interests and a sense of real-world otherness, gamers—especially modders—seem to easily form game-related communities both within and external to the game. In “Of Mods and Modders” Hector Postigo notes that, “The fan culture for digital games is deeply embedded in shared practices and experiences among fan communities, and their active consumption contributes economically and culturally to broader society” (Postigo 300). These game authors/co-creators publicly share their mods, solutions, and experiences, and they are intellectually stimulated through the game’s play, because

“[S]ome degree of technical and social skill is required on the part of the fans contributing content. For example, mappers and modders must have knowledge of scripting languages, graphics programs, and software development kits (SDKs) especially designed for a given graphics engine associated with a game. They must also have knowledge of the history, technology, and architecture if a given time period of the map or mod is historically based.” (Postigo 302).

Minecraft modders, as well as other modders, can locate simple instructions and YouTube videos explaining the necessary free downloads and which Minecraft files they need to access. Anyone who is good at identifying patterns can quickly learn to edit bits of java script and begin writing mods. Because Minecraft’s developers possess a philosophy that is rare in the gaming industry, these modders benefit from their encouragement to modify. While Blizzard Entertainment, responsible for developing World of Warcraft (WoW), and other major game developers include an End User License Agreement (EULA) that limits or even forbids customers from creating any type of modifications to the game, the Minecraft philosophy is different.

<24> Minecraft’s Markus “Notch” Persson began as an independent developer, and his company Mojang retains the nature of a civic-minded independent organization (“Notch”). Even the design of the online “Terms of Use” pages are noticeably different between WoW and Minecraft. The more restrictive WoW is seven pages long, while Minecraft’s fits on a single page with plenty of white space (“WoW”). The WoW site looks and reads like a legal contract sprinkled with discrete sections followed by an accept/reject button(“WoW”). However, the Minecraft site reads like an informal note to a friend explaining simply “What You Get For Purchasing,” “The One Major Rule,” and “What You Can Do” (“Terms of Use”). The WoW document explains in detail that the purchase entitles consumers to alter nothing and observe all official rules. On the contrary, Minecraft blurs the line between producer and consumer by encouraging exploration and modification. Minecraft defines the original product as theirs and mods as yours. Reselling the free game version in part or whole is forbidden, but:

If you’ve bought the game, you may play around with it and modify it. Any tools you write from scratch belong to you. You’re free to do whatever you want with screenshots and videos of the game...Plugins for the game also belong to you and you can do whatever you want with them, including selling them for money (“Terms of Use”).

In contrast, the WoW contract supports the traditional binary of producers who retain game-design creativity and consumers who purchase and use the product. Obviously, this is a hierarchy that privileges the producer by granting him the freedom and creativity to design and distribute the game for profit. In In the WoW model, the gamer-as-consumer receives permission to personalize avatars with the options provided by the game’s designers, to make action decisions for their avatars within the options provided, and to design quests or encounters with others within the options defined by WoW. However, by extending creation and production rights to Minecraft players, Mojang and Minecraft players and modders resist this traditional structure of the consumer/producer binary. Modders, as both consumers and producers of game material, cause the hierarchy to fail. The Minecraft consumer-as-producer now possesses the authority, creativity, and skills to improve the product’s quality—and distribute that new product for a profit. Even Mojang, the developer-producer, benefits from the forward-thinking management of the project’s continued growth and popularity.

<25> Reflecting on the modders’ development of creative communities, Postigo explains that, “[M]odders . . . created modifications and other add-ons because they felt it was an artistic endeavor. Many of them felt that modding . . . was a creative outlet that let them contribute something of beauty” (Postigo 309). Here, Postigo describes the modder as both committed to game creativity and to community building. Creating original modifications achieves both goals. For example, a Minecraft modder identified as “originalluff” shared his in-game project mod for an “Empire of Dirt.” While a mansion made of dirt might not sound very glamorous to those of us in the real world, the luxurious experience of (virtually) sleeping in a structure—complete with decorative wall art and the soft light of flaming torches—provides players with additional comforts in the virtual world. Postigo also notes that, “Modders . . . feel a desire to contribute to their communities and do not necessarily see modding . . . as just art for ‘art's sake'”. For example, one modder states, “I guess what motivates me is the fact that I can make a map or a skin and then see that maybe 10 people like it or even more. I enjoy doing things for others in that way” (Thorn qtd. In Postigo 309). This example from a Minecraft modding forum demonstrates, that modders are devoted to upholding their own community even as they resist other structures.

<26> Even very brief forms of public writing promote civic change. Players who post questions in forums often vary their game play based upon the feedback and instructions they receive from more knowledgeable players. At Minecraftwiki, the tab “Popular and Useful Pages” provides links to pages of descriptions for crafting objects and tools within the game. This page is important because players choosing to play in Survival or Hard Core mode arrive in the Minecraft world with no tools or possessions. Recipes explain how to acquire and use objects already existing within the virtual world—like trees—to make planks of wood which can then be used to build shelter. Obviously, this sort of knowledge alters the way a player interacts with her avatar as well as the way that the avatar interacts with its environment. Minecraftwiki also provides information about mobs of animate life within the game world (MinecraftWiki.net). Receiving this helpful information further dictates how a player’s avatar may safely interact with other inhabitants.

<27> In addition to communal productivity and artistic creativity, some modders use their skills to alter the game’s structural playing field and boundaries. Postigo explains that, “One can say that add-ons in the form of mods, maps, skins, and other components bestow on a game a depth beyond that initially designed by the commercial developers” (Postigo 302). This is especially true for Minecraft modders. When playing in either Survival, Hard Core or Creative mode, the player enters a tabula rasa world of water, earth, air, and sky. Tools, food, shelter, clothing, and character interactions are beyond the scope of the game at this initial stage, although discovering how to make or acquire these objects is possible and encouraged through the Terms of Service Agreement; they simply do not yet exist. However, strong Minecraft modding communities offer advice and mods for building or satisfying the avatar’s needs. Is it snowing? Download and install the fireplace mod. Are you too hot? Build a swimming pool. These mods and add-ons push beyond the limitations imposed by most games’ original playing field, published rules, and developers. Modders expand and extend games through the creation and implementation of their mods. For instance, members of the Minecraft community can locate skins, mods, and texture packs at dozens of sites including Minecraft.net, Planet Minecraft.com, and Minecraftwiki.net. Through these examples of civic discourse, other players also experience new and more challenging play within Minecraft. Through the creation of new skins for avatars, gamers can re-play the same game using characteristics associated with their avatar’s new visual representation. Modifications that allow avatars to fly or that add new levels of challenge also rejuvenate old games, often while extending the realm of play beyond the original developer’s expectations. Because Fullerton discovered the key strokes that allow his avatar to fly, he can now incorporate flight into the avatar’s building and exploring activities. This means that the avatar can cross large bodies of water to build in a location with a different landscape or climate—factors that will further contribute to the actions and behaviors of the players’ avatar.

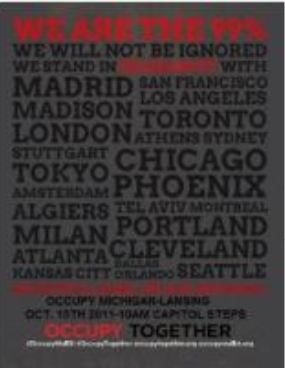

<28> We have already seen how modders demonstrate civic discourse and take action action within the game, but further evidence shows that Minecraft modders also virtually participate in real world protests.

|

Figure 2 |

In fact, “[M]odders tried to make games 'their own' by designing unique elements of game play or importing elements from popular or national culture that had some meaning to them personally” (Postigo 309).

|

Figure 3 |

Because media has naturally been the site of contestation in popular culture, as the Occupy Wall Street movement began to spread in fall 2011, several Minecraft modders created and shared male avatar skins wearing business suits and Guy Fawkes masks. Even art in the form of an appropriate-for-(virtually)-framing “We are the 99%” poster became available to download and install at no charge.

<29> Modders not only resist and play with the structure of their favorite game, they also demonstrate both resistance and assistance to the gaming industry culture. In a single week during November, 2011, Minecraft modders uploaded 136 completed mods to the Planet Minecraft fan site, and updated 1,697 private Minecraft servers. Because of this eagerness to participate and assist the community, modders have also become an important component of the gaming industry’s continued success. Thus, “Many companies have openly acknowledged the value of the content that fans produce. Scott Miller of 3D Realms states that 'developers watched astounded as mods 'actually helped extend the life of a game by providing free additional content for players to explore.' “ (Postigo 308). The computer game industry is an excellent example of the work-as-play ethic, where the term “play-bor” originates. As modders attempt to even the economic playing field by giving away their labor, the game industry often benefits as much as fellow players. Postigo estimates that, “If the average large mod requires more than 1,000 work hours to complete, then, modders have put in more than 39,000 work hours on developing large mods for the top seven titles” (Postigo 305). In fact, he calculates that

“fan-programmers spent more than 115,000 hours working on small additions. If a typical designer for a computer game receives about $45,000 per year for his or her work, then the work on smaller add-ons is worth about $2.5 million in labor costs.” (Postigo 305).

Players who modify games and share their mods provide valuable free community building services to the playing community, and they also provide free game-expanding labor for the gaming industry. Some might argue that play-bor allows the gaming industry to victimize modders, and the potential of profits from fan-created mods is clearly exists. However, modders are not economic victims, even if their modding contributions to their respective gaming communities also benefit the larger gaming industry because the impact of mods has a greater effect upon the game consumers than the game producers.

<30> While some corporations may be recruiting the next generation of game designers from modding forums, others actually reduce their pool of recruits through the prohibitive wording of EULAs. For example, another popular game, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim was originally packaged for sale with a “Creation Kit” and access to “The Skyrim Workshop” wiki so that players could immediately begin modifying the game. The result: “More than two million modifications were downloaded the first week of sales,” and even though Skyrim was not released until November of 2011, it became the second-best selling game in the industry for all of 2011 (Hawkins). This trend shows that the game players who are skilled and creatively motivated to mod migrate toward a game that allows and encourages modding. Furthermore, that Skyrim outsold all other games for 2011 in only 51 days indicates the vast number of players interested in games with modding potential. The economic impact of 2 million skyrim modifications far exceeds an average week of even Minecraft modders. According to Postigo’s estimates, when we consider the 2 million Skyrim mods uploaded during the first week, we find the results of 2 billion work hours. If the average game designer makes $45,000 a year for fifty weeks of forty hours each, then 2 million mods is equivalent to one million game designers earning a combined total of $45 billion in play-bor. In contrast, Minecraft modders’136 mod contribution for the same week amounts to a mere 68 game designers or $3,060,000 in play-bor. Just as the Minecraft modding forum changed an abusive member’s behavior through community ostracism, this level of free play-bor certainly invites the game industry to rethink its Terms of Use agreements.

<31> This text’s attention to Minecraft modders is an example of rhetorical synecdoche in which the Minecraft modding community represents the larger general modding community, including players of other games like Skyrim, Mario Kart, Max Payne, and Mass Effects. It is also an example of rhetorical irony in which the modders’ civic discourse upends the industry’s legal discourse. Modders, like participants of the “Occupy” movement, seek to undermine the social, political, and economic power of the gaming industry, and they accomplish these goals by creating mods. EULAs, like those of Minecraft and Skyrim, embrace the modder as a game co-creator whose work not only popularizes the game but also extends the consumers’ enjoyment of that game. Prohibitive EULAs like those of WoW and Mass Effects drive moders underground or toward other games that embrace mods; therefore, big game corporations like Blizzard and Biodware do not benefit from game mods. Additionally, the very documents designed to protect corporate interest are, through underground modding, providing added value to the end product. This added value neither costs the consumer nor benefits the corporation. In an obviously unanticipated turn, the EULAs fail the big guys. Instead, mods that add challenges or reconceive again, extend the consumer’s enjoyment beyond the game as purchased. In the economy of corporate game producers versus gaming fans, the little guys win big. Minecraft and Skyrim modders, have embraced a similar mission to the “Occupy” participants. These modders are revolutionizing the relationship between game producers and game consumers by taking economic and social power of game design and production from the industry—the 1%—and bestowing that power on the individual game-players—the 99%.

<32> Far from an attempt to bind all modders to a universal code of ethics, this work only presents modders, specifically Minecraft modders, as participants and playful dissidents to and within their modding community, their gaming community, the larger computer gaming culture, and the gaming industry. Minecraft and other modding communities offer further opportunities for investigations of civic discourse. Minecraft modders are social activists for the newer, digital media culture at large, “where you sort of appropriate, re-purpose and recycle digital media.” (Sa). Imagine that, the real world imitating a virtual world by encouraging playful resistance through game play and the creation of a productive community...

Works Cited

“99%.” Planet Minecraft 16 Oct. 2011 web 03 Nov. 2011.

Alcatraz. Lalo. “We Are the 99% Poster.” KPFK 90 FM KPFK web 01 Nov. 2011.

Beggs, Sarah. Personal Interview 03 Dec. 2010.

C418. Minecraft—Volume Alpha C148 web 12 Nov. 2011.

“Dirt Empire.” Planet Minecraft 03 Nov 2011 web 06 Nov 2011.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Eloquence.” The Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson: Letters and Social Aims. Google Books. web 09 Nov. 2011.

Essential Facts about the Computer and Video Game Industry. Entertainment Software Association web 12 Sept. 2011.

“Forum.” Minecraft 17 Oct. 2011 web 07 Dec. 2011.

Fullerton, Eric. “In Search of Diamonds.” YouTube. 21 Nov. 2010 web 10 Nov. 2011.

Guy Fawkes Mask. LeetFeet. web 03 Nov. 2011.

Hourigan, Ben. “You Need Love and Friendship for This Mission!: Final Fantasy VI, VII, and VIII as counterexamples to totalizing discourses on videogames.” Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture. 6.1 (Winter 2006).

Isocrates. Antidosis. Trans. Adam Kissell. University of Chicago. web 01 Nov. 2011.

Johnson, Matthew S. S. “Public Writing in Gaming Spaces.” Computers and Composition web 25 (2008) 270-83.

Kim, Byron. “Synecdoche.” Art Knowledge News Oct. 2006 web 06 Nov. 2011.

King, Joshua. Personal Interview 26 Oct. 2010.

Kűcklich, Julain. “Precarious Playbour Modders and the Digital Games Industry.” Fibrecuture5. Open Humanities Press. 2005. web 10 Oct. 2011.

Lau, Kimberly J. “The Political Lives of Avatars: Play and Democracy in Virtual Worlds.” Western Folklore. 69:3-4 (Summer/Fall 2010): 369-394.

Liz. “Mario: Gentleman, Scholar, Tortfeasor.” Taking Care of Lizness. 14 Oct. 2010. web 04 Oct. 2011.

Minecraft.net. Mojang. web 26 Oct. 2011.

“Modder Spotlight.” Tech Reaction 28 May 2011 web 06 Nov. 2011.

“Notch.” Wired.co.uk 09 Dec. 2011 web 13 Dec. 2011.

“Notch Interview.” Center for Serious Play 02 Mar. 2011 web 06 Nov. 2011.

O’Connor, Dan. “Gamer Evolution.” Robot Geek 25 May 2011 web 13 Nov. 2011.

Planet Minecraft Creative Community Fan Site. Planet Minecraft. 11 Nov. 2011.

Postigo, Hector. “Of Mods and Modders: Chasing down the Value of Fan- Based Digital Game Modifications.” Games and Culture. October 2007 2: 300-13.

Quitilian. “Institutio Oratoria.” Internet Archive. Google. web 01 Nov. 2011.

Sa, Rachel. “Mod Club Crackdown.” National Post, Montreal Edition. The Financial Post. 23 July 2005. web 16 Oct. 2011.

Sanford, Kathy and Leanna Madill. “Resistance through Video Game Play: It's a Boy Thing.” Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l'éducation. Vol. 29. No. 1. The Popular Media, Education, and -Resistance/ Les mass-média populaires. L'éducation et la résistance (2006). pp. 2867-306.

Sotamaa, Ollie. “Have Fun Working with Our Product.” Proceedings of DiGRA 2005 Conference: Changing Views—Words in Play. pp 1-10/

---“On Modder Labour, Commodification of Play, and Mod Competitions.” First Monday. University of Illinois at Chicago. 03 Sept. 2007. web 10 Oct. 2011.

“Terms of Use.” Minecraft web 17 Oct. 2011.

“Terms of Use.” World of Warcraft. web 21 Oct. 2011.

Return to Top»