Reconstruction Vol. 12, No. 4

Return to Contents»

The Tarot of Jane Austen: Re-Envisioning the World / Emily Auger

Abstract: In pre-1970 Tarot gaming decks, trump card XXI typically shows either a cityscape or a semi-nude female dancer inside a wreath surrounded by symbols of the Christian evangelists. More recent Tarot decks, virtually all of which are used for fortune-telling, occult, or personal development exercises, propose many unique variations of this card: card XXI of the Tarot of Jane Austen shows a wedding. This paper considers the significance of the application of this motif, ubiquitous in popular film and literary genres, to Tarot card XXI relative to its conventional iconography and interpretation as established during and after the fifteenth century.

Keywords: Comedy; Epithalamion; Jane Austen; Masque; Playing Cards; Popular Genres; Tarot

Introduction

<1> The Tarot of Jane Austen was designed by Diane Wilkes, illustrated by Lola Airaghi, and published by Lo Scarabeo in 2006. Wilkes also wrote the guidebook associated with the deck. The Tarot of Jane Austen is one of the hundreds of redesigned decks published since c. 1970, most of which are characterized by the five suits that marked the invention of Tarot in fifteenth-century Italy: the fifth suit was originally added to the regular four-suited deck to facilitate the diversity of games that could be played. All of the earliest extant cards are painted, but printed Tarot gaming decks became common from the sixteenth century. Occult interpretations of the cards, particularly the fifth suit, were invented in the later eighteenth century. In the twentieth-century Tarot, no longer used for gaming in North America, became part of the "new age," and acquired a wide range of meditative, psychological, and fortune-telling applications.

<2> The Tarot of Jane Austen is a classic example of the extent to which contemporary Tarot artists and designers have absorbed and adapted the deck to the motifs and goals of popular pictorial and literary genres, ranging from occasion-based photographs, to historical novels, to how-to and self-help books, not to mention various cultural, literary, and mythical traditions. The popularity of such decks is indicated by their quantity (see the on-line in-print listings at the major Tarot deck publishers and distributors U.S. Games, Llewellyn, and Lo Scarabeo) and by the success of such organizations as Tarot Professionals; dedicated Tarot conferences such as Readers Studio; and the activity on various Tarot-related forums on facebook and elsewhere. Wilkes is one of the best-known reviewers of Tarot decks—see her Tarot Passages site at: <http://www.tarotpassages.com/>. She explains that Lo Scarabeo contacted her and offered her:

the opportunity to create a deck on any subject I wanted. As a Jane Austen fan(atic) with a Master's degree in English, I thought that it would be fascinating to create a deck based on Austen's work, connecting each card to a character or scene. It may sound naive, but I really didn't think about how well it might sell, though I did like the idea of Austen fans being able to access tarot reading through their knowledge of her work and I hoped the deck would motivate tarotists to read more (or some) Austen. (Personal Communication 6 December 2011)

<3> Tarot has also become the subject of scholarly research and Tarot artists are welcome at various academic conferences. Wilkes happily reports that a paper on Tarot in general and her deck in particular that she delivered at the Jane Austen Society of North America's (JASNA) Annual General Meeting (Oct. 2009) in Philadelphia, was "well-attended and enthusiastically received."

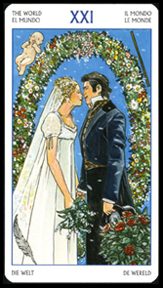

<4> In contemporary Tarot reading practice, card XXI establishes the philosophical or didactic priorities, as well as the object of any given deck's pictorial, symbolic, and/or allegorical sequence. It defines the most desirable of outcomes in life and any situation relative to the particular ideals and context envisioned by the author and deck user. The application of the wedding motif to this particular card in the Austen Tarot (Fig. 1), a card that conventionally shows either a cityscape or a semi-nude female dancer inside a mandorla surrounded by symbols of the Christian evangelists, is consistent with the popularity of the wedding and the affirmation of heterosexual and potentially procreative alliances as the plot resolution and final scene in a vast number of popular novels and films, as well as the objective of many self-help manuals and guides. In this respect, the Austen Tarot is indicative of a not-so-new conservatism in modern day popular culture. And, as this paper shows, this conservatism also lends it an unexpected connection with the evolving conventional message of the traditional Tarot deck.

|

Figure 1: Diane Wilkes and Lola Airaghi (artist). Tarot of Jane Austen. 6.6 x 12 cm. © 2006 Lo Scarabeo. Illus. reproduced by permission of Lo Scarabeo. Further reproduction prohibited. |

The Fifteenth-Century World Card

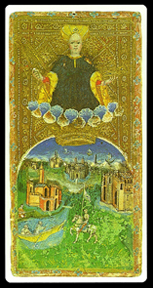

<5> In the fifteenth-century, the unnumbered and untitled cards of the fifth suit were illustrated with designs and images that related to the significant events, people, and beliefs of the day. Wedding scenes were not applied to the card that was later numbered XXI and titled the World; in the earliest extant decks—all of which are painted—the World card typically shows a globe with one or more cities, landscapes, and or seascapes (Dummett 138). This image appears in its most conventional form on the hand-painted fifteenth-century Visconti-Sforza card (c. 1450), which shows the pink-walled city of Milan inside an orb held aloft by two winged cherubs; and the card (late 1400s) from the so-called Gringonneur deck, which shows a haloed female figure standing on top of an orb containing a landscape. In the Cary-Yale card (c. 1445) (Fig. 2), the orb is transformed into an archway.

|

| Figure 2: Cary-Yale Visconti Tarocchi Deck. Facsimile and reconstructed edition created from hand-painted original produced in Milan c. 1445. 9.7 x 19 cm. © 1985 U.S. Games Systems. Illus. reproduced by permission of U.S. Games Systems. Further reproduction prohibited. |

<6> Such images were likely understood as allegorical representations of the city of god transformed into the idealized city of man that was sometimes deliberately associated with specific cities. For example, Helen Farley (2010) believes the Cary-Yale card shows "a pictorial representation of the major powers of northern Italy in the early fifteenth century" (Farley 80). The significance of the fisherman, knight, and boat are uncertain, but the river is likely the 650 km long River Po, and the three cities the major powers in Italy at the time: Milan is identifiable by its red brick, Bologna is on the other side of the river on the far right, the city in the center background is Florence, while that beside the sea in the far background is Venice (Farley 80). Farley argues that the fort in the center may also have been identified with Milan, as such a fort was torn down when Duke Filippo Maria Visconti died, and, in spite of the pleas from the Milanese, rebuilt by Francesco Sforza when he came to the city as its Duke (Farley 81). The crowned arch suggests that, although each of these cities was an independent city state, they are all subject to some centralized or common authority, as does the allegorical figure holding a crown, symbol of sovereignty, and scepter above it. As Farley sums it up, "this card illustrated the pinnacle of Visconti history. Milan acquired vast tracts of territory and wealth through considered conquest, cunning and politics. This was where the trump sequence had been leading: to the Viscontis' dominance of northern Italy and as such, this card can be viewed as an allegory of glory" (Farley 80). Indeed, the Dukes of Milan are associated with the oldest extant Tarot decks, including this one. By the time the French took Milan in 1499, numerous decks were credited to their patronage.

<7> The importance of Tarot in general and card XXI in particular may also be understood relative to various late Medieval and Renaissance cultural practices. In The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family (1966), Gertrude Moakley theorizes that Tarot derived from the popularity of triumphal processions, fashioned somewhat after the Triumphs of the ancient Romans, somewhat after the processions held to celebrate Lent in Medieval times, and somewhat after the fashion of Petrarch's poem I Trionfi written between 1356 and 1374 in six chapters titled Love, Chastity, Death, Fame, Time, and Eternity. Petrarch's chapter titles refer to the power which "triumphs" over the preceding power; thus Love triumphs over both gods and men, Chastity over Love, and so forth until Eternity triumphs over Time (Moakley 45-46). Moakley gives a thorough accounting of the popularity of the triumphal procession in Italy and particularly in the Visconti and Sforza families with which the Cary-Yale deck is associated. For example, "When Constanzo Sforza married Camilla D'Aragona in 1475, the occasion was celebrated by the performance of a Triumph of Fame, with Fame sitting in a car upon a great glove, surrounded by heroes" (Moakley 44).

<8> Moakley finds that the triumph, as represented in Petrarch's poem, is most closely visualized in minchiate decks. The minchiate deck includes, among other figures, the Christian virtues of Faith, Hope, and Charity; the cardinal virtues of Strength, Temperance, Justice, and Prudence, and cards for the signs of the zodiac and elements. Subsequent variations on the I Trionfi theme in paintings and the decorative arts often soften and sentimentalize the story (Moakley 47). It is possible, even likely, that the Cary-Yale deck is a partially preserved minchiate deck. The Tarot gaming deck, Moakley believes, has the character of a "ribald take-off" of Petrarch's poem insofar as Temperance and Fortitude are reduced to companions of Cupid; the Pope is mated with a Popess; Chastity is eliminated, leaving her enemy Fortune to rule; Time is a mere annotation to Death; and Fame is absent. "Most impudent of all," she notes, "Eternity is put on a level with the other triumphs, instead of being unnumbered and so left 'out of this world' as in the minchiate pack. Undoubtedly it was this audacity and irreverence that made the tarocchi trumps so popular, in fact the game of triumphs par excellence" (Moakley 48).

<9> The combination of the triumph of the Universe or Eternity with the city of Milan, whether or not it was meant to be humorous, is entirely consistent with the Visconti and Sforza family ambitions and propagandistic interests. Their power trumps all others. This approach to the World card continues in later decks, such that we see it repeatedly reformulated as a kind of summation of the purported higher interests of the deck patrons.

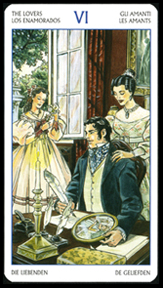

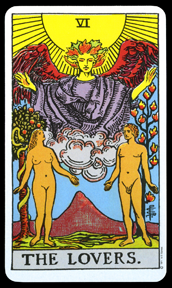

The Marseilles and Rider-Waite World Cards

<10> The World card of the Marseilles tradition, which dates to at least as early as the seventeenth century, is exemplified by such printed decks as the Jean Noblet Tarot (1650) and that associated with Nicholas Conver (1760), and many of its general characteristics are perpetuated in the popular Rider-Waite Tarot (1909) (Fig. 3). In all of these decks, card XXI shows a semi-nude female inside a mandorla with the angel, lion, ox, and eagle associated in Christian iconography with the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John in the corners. According to Michael Dummett (1986), a "Milanese example from a wood-engraved pack of the sixteenth or seventeenth century shows that this version was derived from the standard Milanese pattern for popular tarot packs, but it differs completely from the design for the card in all other packs, popular or hand-painted" (Dummett 138). It did, nonetheless, become the most popular and recognizable treatment of the card in later centuries.

|

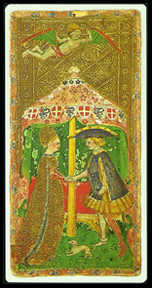

| Figure 3: Pamela Smith (artist) and Arthur Waite. Rider-Waite Tarot®. 1909. 7 x 12 cm. © 1971 U.S. Games Systems. Illus. reproduced by permission of U.S. Games Systems. Further reproduction prohibited. |

<11> This design is an adaptation of a common medieval representation of Christ. Stuart Kaplan (1986) notes that some seventeenth-century decks appear to show a transition from the representation of Christ to that of a woman (Vol. II, 181). He illustrates this point with the World cards from the Vieville deck (c 1643–1664) (307, 308), which shows a nude male figure with a halo, scepter, and robe; the seventeenth-century Jean Noblet deck (307, 309), which shows a similar figure without a halo, but with breasts and a leafy girdle; and the Heri deck of 1718 (314, 317) in which the new convention takes full form as a dancing woman standing on one foot and holding a wand while a ribbon-like scarf swirls about her. All three cards show the figure inside a wreath with the symbols of the evangelists in the corners. Also relevant is the identification of the figure on card XXI of the Jean-Pierre Payen Tarot (c. 1760) (314, 316) as a male Christ.

<12> Kaplan cites at length from George David Wald's [1] account of seeing a series of eighteenth-century tiles in Delft which show an androgynous Jesus: "When seminude, as when beaten by Pilate's soldiers or crucified, he was shown with heavy, pendulous breasts" (Wald quoted in Kaplan II, 180). Noting the varied representations of Jesus as masculine or more feminine, Wald observes that:

The character given God the Father is unalterably male: assertive, aggressive, the God of Battles. In contrast Jesus is gentle, forbearing, forgiving, loving his enemies, nurturing ("Suffer little children to come unto me"), an ostensible male fulfilling a feminine stereotype. The pre-Reformation church and laity at prayer, as distinct from the formal theology, for centuries experienced Jesus as Mother, Sister, and Nurse, as well as King, Knight, Lover and Brother; and developed to go with this attitude an androgynous system of metaphor […]So the idea of Jesus as androgynous is ancient and persistent. What remains a problem is to uncover what impulse in eighteenth-century Europe brought those tilemakers in Delft to portray him so, what made that representation acceptable to purchasers of the tiles, and what made that image for a time so familiar as to bring it onto tarot card XXI. (Wald quoted in Kaplan II, 180)

<13> Robert Place (2013) believes the dancing female nude holding a scepter indicates "her rulership of the physical world. By placing a beautiful woman on the throne of God we have created the visual equivalent of the romantic troubadour ideal of God as the lover who is longed for. The nude in Renaissance art also came to be a symbol of the purified soul. By placing her on the throne of God she represents a mystical state in which the purified soul becomes one with God." Furthermore, the signs of the four evangelists also had associations with the elements, seasons, directions, and so fourth; thus, he writes:

the Christ in Majesty icon was sometimes used by alchemists as a symbol of the quinta essentia (essential fifth element), with the four beasts representing the four physical elements, and Christ representing the mystical fifth element in the central position. For the purpose of clarification, changes were sometimes made, such as exchanging the four beasts for images of the four elements or exchanging Christ for a beautiful nude woman, a symbol of the Anima Mundi, the World Soul.

<14> In keeping with this tradition, Rider-Waite deck (1909) designer Arthur Edward Waite claimed that the card represented "the perfection and end of the Cosmos, the secret which is within it, the rapture of the universe when it understands itself in God. It is further the state of the soul in the consciousness of Divine Vision, reflected from the self-knowing spirit [it is] the state of the restored world when the law of manifestation shall have been carried to the highest degree of natural perfection. [...]" (Waite 156). The divinatory meaning of the card is given as "Assured success, recompense, voyage, route, emigration, flight, change of place. Reversed: Inertia, fixity, stagnation, permanence," but Waite cautions against using the Tarot trumps for divination as the results are likely to be "artificial and arbitrary" (Waite 287). Waite believed that "The allocation of a fortune-telling aspect to these cards is the story of a prolonged impertinence" (Waite 287), simply because he understood them as part of the "mysteries of light" rather than as a proper object for the entirely different order that is fantasy (Waite 287).

<15> The shift in the iconography of the card from cityscape to female nude is not surprising given the decline in the fortunes of Milan and the diversification of patrons of Tarot as the game spread throughout Europe. The symbols for the evangelists would have been recognizable everywhere the Christian church had a presence, and the appeal of a dancing partially-clothed female long outlasted and far exceeded its association with Christian virtue. Just as certain is the deliberation with which this dancing figure is enclosed in a wreath. No longer the external celebrant or comptroller of the World as in the fifteenth-century decks, the female dominating the card has become an object. No longer the one who guards, she is the prize that is guarded, or trapped—depending on your point of view—by some of the most powerful representatives of the written word in the Western world. If the irony of this re-presentation of the World card was not apparent in the seventeenth century or to Waite, it is certainly apparent now.

The Austen World

<16> The Austen World card trades in the dancing nude for a scene inspired by the novel Emma (1815): Emma appears robed and crowned beside her groom George Knightley in a classic "you may now kiss the bride" moment familiar from innumerable novels and films, not to mention weddings themselves and the records kept in family photo albums. Somewhat ahistorically, Emma wears a white dress, a Victorian custom post-dating the novel. The headdress is readily interpreted as indicative of the moment as the woman's "crowning" achievement in life. Wilkes had little control over the visual development of the cards, which was carried out by the artist and publisher. However, she describes this image as "a traditional World card, in that they [the just wedded couple] stand within a wreath of several flowering bushes. The four elements are in the four corners of the card, water symbolized by a baby; fire, a wand; air, a pen; and earth, a flowering bush like the one in the main image" (Wilkes 53). The mandorla and the substitution of the symbols for the evangelists with small symbols of the elements emphasizes the prominence of the central couple.

<17> The entire Jane Austen deck shows the adaptation of cards to specific situations in Austen's novels. Taken in conjunction with the associations and advice provided in the guidebook, the deck becomes a kind of guide to romance combined with what has become a popular fortune-telling tool. For example, the interpretation of the World card provided in the guidebook includes both the prediction of the achievement of "worldly success," and also cautions that the bushes around the couple indicate the ongoing pressures of the world: "Every rosebush contains thorns" (Wilkes 54). Those who receive this card in a reading are advised: "To complain about minor grievances would be small indeed—and not in keeping with the glory of the World card" (Wilkes 54).

<18> In this aspect of its adaptation, the Tarot of Jane Austen shows something of the range of overlapping genres with which Tarot may be associated. The novel is the most obvious of these genres, and specifically the novel devised as a kind of guide to practical, as well as moral, conduct. The ease with which so many literary works have been adapted to Tarot is indicative of this compatibility: the Lord of the Rings Tarot (1997), the Shakespearian Tarot (1993), and the William Blake Tarot of the Creative Imagination (1995, 2010) are just a few of the literature-based decks currently available. We might also add to this discussion the historical novel, film, and Tarot deck, exemplified by the historical novels of Georgette Heyer, the films based on Austen's books, and the Old English Tarot (1996). All of these genres or sub-genres aim to recreate the appearance and at least some of the peripheries of cultural life in another time and place for the amusement and interest of a contemporary audience.

<19> Another genre with which the Tarot of Jane Austen is affiliated is that of the "how-to" or self-help book, in this case, the how-to date successfully or how-to find a husband genre. Most specifically, we may look to Lauren Henderson's Jane Austen's Guide to Romance The Regency Rules (2005) as demonstrative of the affiliation of Wilkes's Tarot guide with this type. Henderson's book includes chapters devoted to such practical pointers in the contemporary dating and romance game as "If You Like Someone, Make It Clear That You Do," and "If Your Lover Needs a Reprimand, Let Him Have It," as well as sections that help the reader determine which Jane Austen character they are, which Jane Austen man they like, and even a compatibility chart. Emma and Mr. Knightley are demonstration characters for the section on reprimanding your lover. Tellingly, in this example, it is Mr. Knightley who chastises Emma on several occasions for selfishly manipulating her friend and for mistreating a kindly neighbor. Emma is, at least at these moments, posed as a naïve and spoiled girl who needs the strong hand of a mature and considerably older male to keep her in line. Mr. Knightley is also, however, the best man available to keep Emma's father happy, and thus keep her inheritance and property intact. This relationship, the one chosen for card XXI of the Jane Austen Tarot, is a relationship that poses a familiar combination of submission to a father-figure and sheer practicality with respect to worldly comforts, assets, and indispensable family members.

<20> Another text that readily aligns with the Tarot of Jane Austen and Jane Austen's Guide to Romance is Corrine Kenner's Tall Dark Stranger: Tarot for Love and Romance (2005). This guide to reading Tarot makes no reference to Jane Austen, but it does offer suggestions for the use of Tarot and reading the cards in relation to matters of romance and love. The interpretations for card XXI promote the user's identification with the "joyful, self-assured, young woman in the center of the card" (Kenner 140), apparently a reference to the dancing nude of the Marseilles tradition. The author goes on to reference some of the traditional meanings of the card, and also writes: "In a romance reading, the World could signify that you and your traveling companion have arrived at the station together. And if you're still looking for romance, you have come to the right place" (Kenner 141). The four symbols in the corners are allied with astrological signs, the dimensions, directions, seasons, winds, moon phases, and ages of humankind, but not the Christian evangelists.

The Virtues and the Lovers

<21> The Jane Austen World card shows marriage as a kind of pinnacle of achievement or "trump," and thus represents the specific outcome of the traditional card VI of the deck, typically labeled Love or The Lovers. The Austen Lovers card (Fig. 4) represents a point in Pride and Prejudice (1813) when Mr. Darcy is discovering his preference for Elizabeth over Miss Bingley. The image design is modeled after the Marseilles version of the card (Fig. 5); the equivalent Renaissance cards display a couple, apparently being blessed by a cupid or angelic figure.

|

| Figure 4: Diane Wilkes and Lola Airaghi (artist). Tarot of Jane Austen. 6.6 x 12 cm. © 2006 Lo Scarabeo. Illus. reproduced by permission of Lo Scarabeo. Further reproduction prohibited. |

|

| Figure 5: Ancient Tarot of Marseilles. Exact facsimile of original by Nicholas Conver, Marseilles, 1760. 6.6 x 12 cm. © 1995 Lo Scarabeo. Illus. reproduced by permission of Lo Scarabeo. Further reproduction prohibited. |

<22> The historical revision of the Lovers is best understood in relation to the revision of those cards representing the Christian virtues. Cards for all three Christian virtues: Charity, Faith, and Hope, are found in the minchiate-like Cary-Yale deck. All three of these cards show a large central female figure and a small male figure at the bottom of the card, apparently representing temptation away from the path of virtue. The virtue of Love was understood in association with Charity at this time and, as such, it was represented on a card distinct from the actual Lovers card, which represents marriage, not necessarily love per se.

<23> The three Virtues are much transformed in the Visconti-Sforza, Marseilles, and later Tarot decks, such that Charity and Faith are replaced by the High Priestess and Pope—neither character is to be found in the extant cards of the Cary-Yale deck—and in the Marseilles deck Hope is apparently replaced by a nude woman with stars over her head. Thus the allegorical abstractness of the Cary-Yale Charity and Faith is exchanged in the fully developed Tarot deck for professional, if not personal, identifications, while the idealism of Hope is somewhat maintained by what may be a not so subtle allusion to sexual desire. As Moakley observed, humour is a mainstay in Tarot imagery.

<24> The Cary-Yale Lovers (Fig. 6) shows a couple clasping hands beneath a pavilion; a small dog symbolizes fidelity, a red bed suggests passion, and a green drapery fertility. The winged blindfolded cupid-like figure above the scene has two arrows, one for the man and one for the woman, but no bow (Kaplan Vol. II, 164). This card is believed to commemorate a specific marriage, though which marriage is the basis of some discussion, Kaplan believes the figures "may represent Duke Filippo Maria Visconti and either his first wife, Beatrice di Tenda, or his second wife, Maria of Savoy [1428]. […] Alternatively, the figures may represent Bianca Maria Visconti and Francesco Sforza [1441]" (Kaplan I 89). When Filippo's older brother, Giovanni Maria Visconti, the second Duke of Milan, was murdered in 1412, Filippo became the third Duke of Milan. Filippo had his first wife Beatrice beheaded in 1418, purportedly for adultery and married Maria of Savoy in 1428. Filippo also had an illegitimate daughter Bianca Maria Visconti (b. 1423) who, at the age of nine, was betrothed to the condottiere Francesco Sforza. They were married when she was eighteen in 1441 (Kaplan I 60). In 1450, Francesco won his right to the title of fourth Duke of Milan. As Kaplan elaborates, "Milan did not pass smoothly to Francesco by inheritance, but by 1450 Francesco realized his ambitions and became the fourth Duke of Milan. He was the first Sforza to hold the title and the only condottiere to rise from humble origins to become a duke" (Kaplan I 61).

|

| Figure 6: Cary-Yale Visconti Tarocchi Deck. Facsimile and reconstructed edition created from hand-painted original produced in Milan c. 1445. 9.7 x 19 cm. © 1985 U.S. Games Systems. Illus. reproduced by permission of U.S. Games Systems. Further reproduction prohibited. |

<25> Kaplan cites Ronald Decker's argument in favor of the later marriage as the reason for the commissioning of the Cary-Yale pack:

In the sixty-seven-card Cary-Yale pack, the costumes in the suit of swords are decorated with a Sforza quince or a branch bearing leaves and flowers. A large fountain, also thought to be an early Sforza device, is used in the suit of staves. The remaining suits bear Visconti devices—crowns with branches or fronds in the suit of cups and pelicans or doves in the suit of coins. Thus, two suits in the Cary-Yale pack contain Visconti devices and two contain Sforza devices, leading one to speculate that the deck was prepared about the time of the wedding in 1441 of Francesco Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti, each family equally represented by two suits. Furthermore, The Lovers card depicts what may be the marriage scene and the aged figure depicted as the king of cups may represent the bride's father, Filippo Visconti. (Kaplan I 107)

<26> Francesco Sforza was not only Duke of Milan, a title indicated by the serpent crest on the Lovers card pavilion; he was also the Prince of Pavia, a title indicated by a white cross on red, also present on the pavilion (Kaplan I 106). The Cary-Yale deck may, therefore, have been commissioned on or for the occasion of the marriage of Francesco Sforza to Bianca Maria Visconti in 1441.

<27> Marriage, specifically the moment at which the marriage contract is validated, has often been the subject of literature, literature that is often comic. Indeed, the epithalamion [pl. epithalamia] was originally a Greek song invoking blessings for a bride and groom, which the Romans transformed into an occasion for obscene jokes. It is known today as it appears in Edmund Spenser's 1597 Epithalamium and Shakespeare's play A Midsummer Night's Dream, not to mention the infinite number of Hollywood-style films and stories which conclude with a marriage agreement or some alliance between a procreating man and woman. As Northrop Frye (1957) demonstrated, the wedding is the classic conclusion of the comic mode. He writes, "The theme of the comic is the integration of society, which usually takes the form of incorporating a central character into it. […] The comic hero will get his triumph whether what he has done is sensible or silly, honest or rascally" (43). Frye further notes that pure comedy often celebrates a "happy society" by incorporating "music and dancing" and, ideally:

becomes the masque. The masque—or at least the kind of masque that is nearest to comedy […] is usually a compliment to the audience, or an important member of it, and leads up to an idealization of the society represented by that audience. Its plots and characters are fairly stock, as they exist only in relation to the significance of the occasion.It thus differs from comedy in its more intimate attitude to the audience: there is more insistence on the connection between the audience and the community on the stage. The members of a masque are ordinarily disguised members of the audience, and there is a final gesture of surrender when the actors unmask and join the audience in a dance. (287-88)

<28> It is not difficult to extend Moakley's interpretation of Tarot to include the comedy and masque, since the patrons of the cards were likely those shown being integrated into society in the Renaissance Lovers cards, or else the patrons were related to those individuals by blood or alliance. The "masque" component of comedy is similarly evident in today's popular fortune-telling practices, which use the cards as stand-ins for the querent and their situation.

<29> In Marseilles decks, the specific marriage ceremony is set aside in favor of a generic representation of what often appears as a man choosing between two women. On the Noblet and Conver deck cards, a man is shown with two women while a cupid prepares to fire his bow at him. As Mary K. Greer (2013) explains, the second woman has been variously interpreted as a chaperone or matchmaker, perhaps even Venus herself, or as an indication that the man is choosing between two women. These alterations increase the potential for humorous associations and interpretations of the card.

<30> The comic element seems to have been abandoned in the Rider-Waite deck insofar as the Lovers are presented in a Christianized allegory of marriage based on Adam and Eve (Fig. 7)this change is consistent with Waite's declared opposition to the use of the cards for what he regarded as frivolous pursuits:

Behind the man is the Tree of Life, bearing twelve fruits, and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil is behind the woman; the serpent is twining round it. The figures suggest youth, virginity, innocence and love before it is contaminated by gross material desire. […] It replaces, by recourse to first principles, the old card of marriage. (Waite 92)

|

| Figure 7: Pamela Smith (artist) and Arthur Waite. Rider-Waite Tarot®. 1909. 7 x 12 cm. © 1971 U.S. Games Systems. Illus. reproduced by permission of U.S. Games Systems. |

<31> According to Greer's analysis, Waite intended to revise the old story so that Eve would be understood less as a temptress and more as the working of a "Secret Law of Providence," as it is by the "providential Fall" with which she is associated that man leaves the garden and enters adulthood (Greer 2013). Eating the apple means setting out on the path to higher knowledge, or to Gnosis, represented in the card as an angel presiding over the Lovers (Greer 591). Card VI thus changes from a representation of a specific marriage, to the image of a man choosing his bride, to the idealized and mythologized representation of marriage.

<32> In the Tarot of Jane Austen, the cards that once represented the virtues, like those in the rest of the Austen deck, are all revised so that they serve the World card goal of a heterosexual marriage. The figures wear masks from Austen's novels. The High Priestess is Jane Austen. The Pope is none other than Mr. Collins of Pride and Prejudice. The Star is reorganized to emphasize a moment from Persuasion (1817) in which the heroine, long and much diminished in her would-be lover's eyes, has reaffirmed her worth by acting quickly and effectively to save the life of a somewhat foolish girl. The Lovers card shows Darcy choosing the "right" woman in Pride and Prejudice (1813). The choice of this particular event for this card suggests the notion of competition between the two women as much as it does the man's freedom of choice.

Conclusions<33> Tarot card VI representations of a heterosexual couple in a contracted union appear to be direct prototypes for the Tarot of Jane Austen World card. As card VI, the heterosexual couple is posed as one element of a larger social project signified by the World card; as card XXI, this first trump of "Love" becomes the grandest triumph of a woman's life. The Austen card image has little to do with any particularly Christian sacrament or allegory, but it does have a great deal to do with one of Austen's favored modes—the comedy. Readers using the Austen cards as masks will find their every action interpreted relative to a competition for Mr. Right. That a woman, Austen as High Priestess, is in charge of this plot dramatizes the tale as one of a woman's making, that a woman is the author of this (comic?) narrative. The assertion of a woman's authorial right is, in effect, validated here only insofar as it fosters the presumption that a woman's principal goal in life is to win the matrimonial ring from her chosen male: the image on the final Tarot World card establishes this limitation. The Tarot of Jane Austen card XXI echoes the didactic message conveyed by earlier decks, albeit only a specific and redirected part of that message. The Cary-Yale and Visconti-Sforza World cards celebrate the triumph of Milanese power over other Italian city states: Milan is thus declared the guarantor of the "world." In the Marseilles and Rider-Waite World cards, the church, symbolized by the signs of the evangelists, replaces Milan; given that the image of the city is replaced by that of a woman, it may seem more like a guard assuring containment than a guardian or guarantor. In the Tarot of Jane Austen World card, true to the comic mode that inspired Austen and likely the first inventors of Tarot as well, a woman at least partially subverts this containment by authoring her own place in society, and by repositioning the triumph of marriage so that it replaces the state and the church as the "world's" guarantor.

Endnotes

[1] The original unpublished manuscript is "The Symbolism of Tarot Cards XVI and XXI," 1982. The Papers of George David Wald (1927–1996) are held in the Harvard University Archives. (See box 114 and others listed at: <http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~hua02000>.

Work Cited

Dummett, Michael. The Visconti-Sforza Tarot Cards. New York: George Braziller, 1986.

Farley, Helen. A Cultural History of Tarot: From Entertainment to Esotericism. New York I.B. Tauris, 2009.

Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. 1957. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1971.

Greer, Mary K. "A Iconographic History of the Lovers Card." Tarot in Culture. Ed. Emily E. Auger. Victoria, Aus.: Association for Tarot Studies, 2013. Forthcoming.

Henderson, Lauren. Jane Austen's Guide to Romance The Regency Rules. London: Headline Book Publishing, 2005.

Kaplan, Stuart R. The Encyclopedia of Tarot. Vol. I (1978) and Vol II (1986). Stamford, CT: U.S. Games Systems.

Kenner, Corrine. Tall Dark Stranger: Tarot for Love and Romance. St. Paul: Llewellyn, 2005.

Moakley, Gertrude. The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family: An Iconographic and Historical Study. The New York Public Library, 1966.

Place, Robert. "Iconography and Allegory in Fifteenth to Seventeenth-Century Trumps." Tarot in Culture. Ed. Emily E. Auger. Victoria, Aus.: Association for Tarot Studies, 2013. Forthcoming.

Waite, Arthur Edward. The Pictorial Key to the Tarot. 1910: York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1983.

Wilkes, Diane. Tarot of Jane Austen [guidebook]. Deck illustrations by Lola Airaghi. Torino, Italy: Lo Scarabeo, 2006.

Return to Top»