Reconstruction Vol. 12, No. 4

Return to Contents»

Toward a Concept of Post-Postmodernism or Lady Gaga‘s Reconfigurations of Madonna / Danuta Fjellestad and Maria Engberg

Abstract: How can we describe the landscape of what is increasingly referred to as post-postmodernism? Is post-postmodernism but a revision (however significant) of postmodernism or is it a new, perhaps even original, episteme? As must be clear from the title, the article takes Ihab Hassan‘s much discussed essay “Toward a Concept of Postmodernism” as its point of departure, but proposes a double revision of his chart. First, it supplements the chart with a set of concepts used to designate post-postmodernism. Second, it provides a re-vision of the very layout of the chart, arguing with Johanna Drucker that form is constitutive of information rather than its transparent presentation. The reference to the Madonna - Lady Gaga relationship in the essay‘s subtitle signals that the seismic shift—if that is what it is—that we endeavor to map is palpable in popular culture as much as in critical and theoretical discourses. Whether we find ourselves at the point of unfolding or at the peak of this new épistémè, it is indisputable that the broad cultural and societal changes of the past two decades are related to digital media. Taking our cue from Lady Gaga‘s performances, we suggest that two distinct features of contemporary culture, access and excess, be seen as interlinked characteristics of the post-postmodern.

Keywords

<1> Prompted by the current intellectual debates about what may have displaced postmodernism, debates predicated on a deeply felt sense of a sea-change, this essay‘s spectral figure is Lady Gaga. One day, while excitedly arguing if what was going on today was but a revision (however significant) of postmodernism or an emergence of a new, perhaps even an original, épistémè, we saw a snippet of a music video with Lady Gaga. We were electrified: Was this lavish spectacle of a blond writhing with reckless abandon but a reincarnation of Madonna? Was Lady Gaga an artist who with zest and cunning explored what Madonna initiated once upon a time? Or has Lady Gaga eclipsed Madonna? If so, how could we read this eclipse? Not quite sure what to think—or indeed how to describe our emotional and aesthetic responses to what we saw (and of course to what we heard, though Lady Gaga‘s music and lyrics made no lasting impression on us), but sensing the significance of the moment, we rushed to the Internet to review the video (available at numerous sites, among others, http://www.casttv.com/video/tmi2f7/lady-gaga-telephone-ft-beyonc-video). As we surfed on, we stumbled upon an online journal, Gaga Stigmata: Critical Writings and Art about Lady Gaga. Established in March 2010, the journal is a treasure trove of information about Gaga, introduced by the editors as a “brazenly unserious shock pop phenomenon and fame monster” (see http://gagajournal.blogspot.com/p/about.html). We soon learned that we were far from the only ones to ponder the Lady Gaga-Madonna connection. We discovered soon too that we could not come to an agreement on our interpretation of Gaga; traces of this unfinished dialogue between us can be spotted in the essay. We have retained them to keep the discussion about the Gaga-Madonna relation open. For both of us, though, Lady Gaga has turned out to function as a convergence figure for what philosophers, sociologists, psychologists, theologists, media studies scholars, literary critics, and numerous others were trying to figure out in the books and essays that we so diligently read. She is a pop-cultural embodiment of a seismic shift in today‘s society and culture, a shift that always already entails the past (read: Madonna) that it is so eager to leave behind. But we are running ahead of ourselves.

<2> Lady Gaga‘s Telephone music video was a strange but significant addition to our collection of material that in one or another way signaled a move beyond, post, or after postmodernism. Indeed, at that point our shelves were heavy with books whose titles appeared to announce that we had left the postmodern behind.[1] More often than not, on having read the newly arrived book (or, for that matter, essay), we felt quite distressed, since what was offered was but taking stock of or re-thinking, re-visiting, and re-reading postmodernism—or indeed arguing for its very existence—rather than discussing the beyond, post, or after. Fortunately, once in a while we encountered adamant claims about all of us having moved into a new cultural paradigm accompanied by attempts to identify some distinguishing features of the new. So we began to toy with the idea of systematically mapping the various propositions about our current cultural moment in a way reminiscent of Ihab Hassan‘s interesting—if controversial—effort to chart differences between modernism and postmodernism. [2] It is not our aim to engage in polemics with Hassan; rather, both inspired and challenged by his attempt to define postmodernism, we wonder what an effort to describe the contours of today‘s cultural landscape may look like. We are of course acutely aware that postmodernism has never been accepted by some theoreticians, while those who have promoted it are not in agreement as to the period‘s main characteristics. We are aware, too, that to locate dominant sensibilities and to make comprehensible the complex and dynamic forces in any culture at any time, one needs, inevitably, to resort to reductions and simplifications. Most of all, we cannot not be aware of all kinds of risks when speaking about historical periods, not least the risk that rather than designating a reality period terms tend to fabricateit.[3] This risk we are willing to take.

| * * * |

<3> There is no lack of voices announcing the waning—death even—of postmodernism. Writing toward the end of the 1990s, Hal Foster declared that “postmodernism became démodé” (206); at the beginning of the twenty-first century, Jóse López and Garry Potter stated that that as an intellectual phenomenon postmodernism had “gone out of fashion” (4); for Johanna Drucker and Emily McVarish, “by 2002 … the blush of postmodernism was long past” (307). Ironically enough, it is the very critics who tirelessly and prolifically made postmodernism familiar to broad audiences that have declared that the period has ended. When speaking about postmodernism in the epilogue of the second (2002) edition of her influential Politics of Postmodernism, first published in 1989, Linda Hutcheon resorts to the past tense, writing that “the postmodern may well be a twentieth-century phenomenon, that is, a thing of the past” (165). Similarly, Ihab Hassan and Brian McHale signal the pastness of postmodernism by raising the question “What Was Postmodernism?” [4]

<4> But if postmodernism is “dead and buried” (Kirby, “The Death of Postmodernism” n.p.), how can we refer to the present moment? A handful of terms have been proposed to label the trends that allegedly come after postmodernism. For instance, Eric Gans promotes the notion of “post-millennialism,” Raoul Eshelman “performatism,” and Alan Kirby “digimodernism.” Like Kirby, a number of critics attempt to revalorize the notion of modernism by adding a variety of prefixes. Thus we hear about “Remodernism” (Katherine Evans), “Retro-Modernism” (Jim Collins), “Supermodernism” (Paul Crowther), “Hypermodernism” (Gilles Lipovetsky), “Metamodernism” (Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker), “Altermodern” (Nicolas Bourriaud), “Automodernity” (Robert Samuels), “Critical Modernism” (Charles Jencks) or “cosmodernism” (Christian Moraru).[5] None of these terms, however, is as popular as that of “post-postmodernism,” which appears to function as a useful—if not unproblematic—shorthand for what is understood as a turn away from postmodernism. Judging from the increasingly causal way in which the coinage “post-postmodernism” tends to be used, it may very well establish itself even before its meaning is defined.[6]

<5> If postmodernism sounded “awkward” and “uncouth” to Hassan, post-postmodernism may sound downright ridiculous in its doubling of the “post” that suggests a certain terminological poverty as well as a chronological movement forward in disregard of the heated debates about periodization. On the other hand, the doubling of the post may not be all that strange. For quite some time, after all, we have heard about all kinds of posts (as in the posthuman, posthistorical, postclassical, post-print, post-textual, post-feminist, post-gender, post-literate, post-theory, post-Cold War, post-industrial, post-national, post-baby boom, post-9/11, etc.). Increasingly, pronouncements of the post- computer (or post-PC) era are made, as mobile digital devices become ubiquitous. Thus to the “post-everything” Generation Y (also called the Net Generation) the term post-postmodern may not sound as graceless as to those who found postmodernism a coarse and ungainly concept.

<6> Whence has the term “post-postmodernism” come? When did it make its entry? David Foster Wallace mentions in passing the word “post-postmodernism” to refer to a fictional subgenre that adopts “the hoary techniques of literary Realism to a ‘90s world” (51). [7] The concept may also be found in the title of John E. Willis‘s article published in 1995. In “Post-Postmodern University” Willis seems to conceive of the post- postmodern as a bridge between what he sees as polar orientations in postmodernism: hypermodernism and neopragmatism. A similar reconciliation of sorts is proposed by Tom Turner, a town planner and landscape architect, who uses the term in the subtitle of his 1996 book, City as Landscape: A Post-Postmodern View of Design and Planning. Although he finds post-postmodernism “a preposterous term” (10), he deems it useful to describe a reaction to the postmodern “anything goes” eclecticism and to signal the turn to faith in an attempt to “temper reason” (9) and to describe signs of post-postmodern life in “urban design, architecture and elsewhere” (8). If there are any earlier uses of the term, they have not come to our attention.

<7> Although we know that unlike new concepts, the entrance of new periods cannot be pinpointed to any specific date or place, it is tempting to feel inspired by Virginia Woolf (who dared to claim that human nature changed on or about December 1910) or by Charles Jencks (who announced that the death of modern architecture took place on 15 July 1971) and seek a birthday of post-postmodernism. Sometimes the turn from the second to the third millennium is proposed as a convenient marker of social, political, and cultural changes. Steven Best and Douglas Kellner, for instance, find the Third Millennium “useful as a marker that indicates we are moving into new constellations” (Postmodern Adventure 6). Sometimes the death of postmodernism is linked to the most terrifying and spectacular event at the beginning of the third millennium: the atrocities of September 11, 2001. For Alan Kirby, “postmodernism was buried in the rubble of the Twin Towers” (226). For Terry Eagleton, the end of the “style of thinking known as postmodernism” came “along with the so-called war on terror” (After Theory 221). Undoubtedly, 9/11 will remain an important historical point of reference and thus a useful watershed marker. But as Best and Kellner observe, “historical epochs do not rise and fall in neat patterns or at precise chronological moments” (Postmodern Turn 31). A shift from one paradigm to another entails a period of coexistence of the old and new modes of social and cultural production, a period of gradual retreat of the old and equally gradual intensification and advance of the new. Thus, in our view, it is not so much the dramatic historical event of 9/11 as a whirl of technological innovations during the last few decades that has brought about the paradigm change. In other words, we align ourselves with critics like Jay David Bolter or Jerome McGann who see the arrival and effects of the Internet and the World Wide Web as ushering profound societal and cultural transformations. [8] Indeed, what Jacques Derrida wrote about electronic mail is true of the whole Internet: it is “transforming the entire public and private space of humanity” (Archive Fever 17).

<8> Writing in the mid-1990s, Derrida could hardly foresee the speed and gravity of transformation of every aspect of our lives under the pressures of Google, Amazon, Wikipedia, YouTube, Flickr, Wikileaks, eBay, iPod, iPad, Facebook, Kindle, blogs, Twitter, podcasting or file-sharing. In the span of a decade or so these information and communication means reconfigured all social, political, economic, and cultural domains. It is in particular the rapid spread of social media that can be linked to the post-postmodern. So although we do not agree with Lev Manovich that we have moved from media to social media, we do share his view that today‘s media universe is “not simply a scaled-up version of twentieth-century media culture” but a distinctly different formation (319). No wonder that we observe a plethora of terms such as The Digital, Internet, Google, or Information Age, or, perhaps, at this point The Information Overload Age, alternatively called The Attention Age, to signal increasing commoditization of attention linked to the emergence of Web 2.0 and social media. More than ever before it is impossible today to separate the cultural from the technological, since virtually all facets of human life are intricately entwined with networked media. This entanglement between digital technology and cultural phenomena should not be seen in terms of technological determinism. “Rather than determining our situation,” as W.J.T. Mitchell and Mark Hansen, observe, “media are our situation” (xxii; emphasis in original). The neologism “technoculture” captures well today‘s interlacing of technology and culture.[9] And today technology is virtually synonymous with digital media. No wonder that the term has gained such currency in academic and popular discourses.

<9> In what terms can we describe the landscape of what is increasingly referred to as post-postmodernism? Our—arguably incomplete— “distant reading” of debates about the current moment has yielded a number of results most of which we present as additions to Hassan‘s chart. Below we review, pell-mell, a handful of what we see as the most intriguing trends in some detail.[10]

<10> Generally, while postmodernism tended to be described in “terms of unmaking” (Hassan “Toward” 92), such as deconstruction, disintegration, displacement, delegitimization or dissolution, today‘s discourses are saturated with terms of re-making. Thus we remix, reconfigure, remediate, recombine, reorganize, reengage, relocate, recontextualize, reassess, reposition, remythologize, reconstruct, revoke, reconstitute, recollect, recast, rebrand, reframe, remap, revisit, repurpose, remobilize, rethink, reinterrogate, rearticulate, reconceptualize, recompose, reevaluate, redirect, rerun, renew, reconsider, reshape, refashion, and even rehumanize. This change of prefixes from “de-“ to “re-“ marks a shift from the stance of negativity and opposition, of tearing matters apart to that of stitching things back together, of going back to previously held positions and convictions to revive and reconfigure them.

<11> And indeed the discussions about what supersedes postmodernism are filled with invocations of “returns.” What we have returned to, if we are to believe a variety of critics, is human values and common sense, the human subject and subjectivity, reason, the real, realism, faith, trust, and religion. [11] Nor is there a shortage of books and articles that announce a return to —or a need to return to—aesthetics, beauty, close reading, the lyric, and ethics. [12] Such returns seldom—if ever—entail simply going back to the pre-postmodern mode of thinking. Some of them are powerfully inflected by postmodernism, while others mean a shift from a position of marginality in postmodern debates to the center of attention today.

<12> In An Awareness of What Is Missing, Jürgen Habermas argues that today we speak of what was missing in discussions of the 1970s and 1980s: religion, faith, knowledge, and reason. What he does not say, however, is that we witness a return to what in the postmodern era was regarded as debunked and erased as an intellectual thought: Master Narratives. We speak about a return to rather than of to emphasize that while we see many grand narratives operating unquestioned in today‘s discourse, they are different from those that Jean-François Lyotard and others critiqued in their work. Among the new grand narratives the one of globalization is undoubtedly one of the better known. According to this narrative, virtually everything seems to have been globalized: markets, economy, politics, wars, cultures, subjects, cities, citizenship, poverty, babies, terror, health, you name it. In this imaginary, the globe has replaced the nation as an arena of trends, actions, and developments. Both the proponents and the opponents of the inexorable process of globalization assert that it is predicated on the world being “wired”: the Internet enables effortless transnational flows of goods and ideas, allows availability, and transforms the world into a complex network. Ursula K. Heise‘s claim about the centrality of a “sense of planet—a sense of how political, economic, technological, social, cultural, and ecological networks shape daily routine” (55) dominates not only ecological awareness but our culture at large. As we will argue toward the end of the article, the real and imagined state of global connectedness, of access, can be seen as one of the most distinctive features of digital culture and, by extension, post-postmodernism.

<13> Another master narrative pitches biology as the center of attention today. Genetics, genome, DNA, evolutionary biology, biotechnology, neuroscience, bionics, cloning, and stem-cell research have become articles of faith that all but replaced the credo of constructivism so central to postmodernism. This varied and complex narrative of the role of biology today resonates with the discourses on environment, ecology, and ecosystems that form a constellation of yet another grand narrative that is firmly planted in popular consciousness today.

<14> Lest the rise of new grand narratives be understood to mean that the post-postmodern is homogenous, let us emphasize that in any period one can find a number of contradictory, conflictual, and incommensurate tendencies. Post-postmodernism is of course no exception. Thus, for instance, the claims about our time‘s fluidity clash and coexist with a simultaneous interest in materiality and embodiment.[13] Fluid selves, fluid races, fluid genders, and fluid economies are subject of investigation side by side with renewed explorations of “thingness” (not least the thingness of books) and the dawn of what may be called “Thing Theory.” [14] Calls for new sincerity and earnestness collide with sensationalism and exploitative voyeurism; virtual reality competes with TV reality shows such as the Big Brother; an interest in documentary forms is on the rise at a time of widespread use of computer graphics editing. And of course the pronouncements of the global era are in fissure with the narratives of ethnic nationalism.

<15> However, the discussions promulgating a new period are less focused on what trends coexist than on pointing to shifts and changes. We would like to mention two such shifts. One is a shift toward the visual and the other toward realism.

<16> In the past two decades we have witnessed a veritable eruption of research converging on all things visual across a range of disciplines, from sociology to philosophy, pedagogy, politics, cognitive psychology, history of science, performance studies, and gender studies (to name just a few), along with traditionally more image-focused areas of research as art history, film studies, television studies. At this point in time, in fact, the sub-field of visual culture studies threatens to subsume under itself many of the traditional disciplines (such as art history) as well as more recent “shadow disciplines” (such as film studies), to use James Chandler‘s term (737).

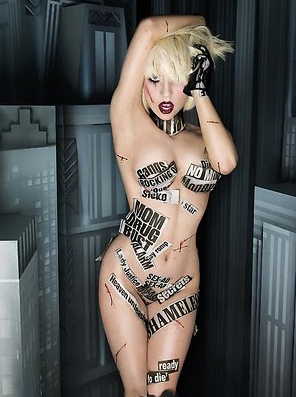

<17> This shift toward the visual was foretold by W.J.T. Mitchell in the early 1990s and dubbed “The Pictorial Turn,” the turn that in popular culture is so well illustrated by the image of Lady Gaga‘s naked body but for paper strips with words on them.

|

| Lady Gaga, photo by David LaChapelle |

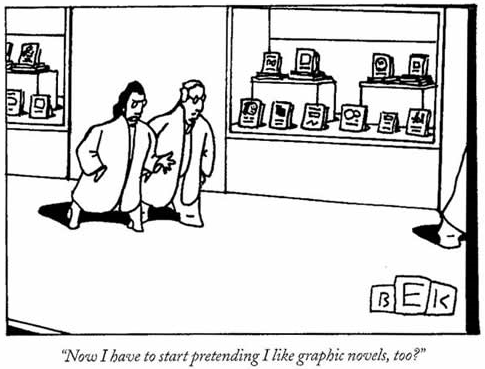

More importantly, an increasingly important part of the pictorial turn is the production of and critical interest in narratives that combine the verbal with the visual. The growing academic interest in the graphic narrative is perhaps the best example of this type of narrative. [15] While graphic narratives have of course a long history and while the first volume of the much celebrated Maus was published when the postmodern paradigm was running strong, what can be dubbed a “comics turn” is decidedly a phenomenon of post-postmodernism. For decades disdained by literary scholars as sensationalistic, cheap, trashy, and banal, comics have come to enjoy an astonishingly high cultural status of late and are the object of scholarly conferences and journals.[16] As Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester write, “A cohort of graphic novels … have become standard items on college and university syllabi for courses on memoir, cultural history, postmodern literature, and area studies. The notion that comics are unworthy of serious investigation has given way to a widening curiosity about comics as artifacts, commodities, codes, devices, mirrors, polemics, puzzles, and pedagogical tools” (xi). There is little doubt that graphic novels such as Art Spiegelman‘s Maus, Marjane Satrapi‘s Persepolis, Linda Barry‘s One Hundred Demons or Alan Moore‘s Watchmen are complex and sophisticated works that are quickly becoming part of literary canons. Rather than “a byword for banality” (Heer and Worcester xi), comics and graphic narratives are found today intellectually stimulating and are studied with the seriousness reserved earlier for high-cultural forms by scholars such as Charles Hatfield, Scott McCloud, Thierry Groensteen, and Hillary Chute. This overwhelming shift in aesthetics is well captured in Bruce Eric Kaplan‘s cartoon, published in 2004 in The New Yorker. It shows two people passing by a bookstore. One of them complains, “Now I have to start pretending I like graphic novels too?”

|

| Bruce Erik Kaplan, The New Yorker, 12/13/2004 |

<18> Kaplan‘s cartoon couple may be surprised by the sophistication and experimentation of graphic fiction as well as other forms of popular culture that have appropriated many of the aesthetic strategies of “high” modernism and postmodernism alike. Indeed, today self-reference, intertextuality, linguistic games, labyrinthine plotting are part and parcel of virtually many mainstream cultural productions; supermarket best-sellers like Stephen King‘s The Dark Half or television serials like Lost share the distinctive stylistic features of postmodernist novels such as Thomas Pynchon‘s Gravity‘s Rainbow. Computer games have become popular far beyond their initial teenage audience, their complexity and diverse genres analyzed by a whole host of “game studies” scholars (for instance Espen Aarseth, Jesper Juul, Ian Bogost, Janet Murray) at conferences, in academic journals, and professional organizations. There is a more diverse audience for computer games today as the popularity of casual games for platforms such as smart phones exemplifies.

<19> A widening audience and increased academic interest go for many television programs, especially serial shows such as The Sopranos (HBO, 1999-2007), The Wire (HBO 2002-2008), Lost (ABC, 2004-2010) or Mad Men (AMC 2007--), whose intricate plotting, sophisticated intertextuality, and camera work have been hailed by broad audiences as much as by academic scholars. As media scholar Jason Mittell has argued, these shows (and others like them) exhibit a high degree of narrative complexity and formal experimentation, once the domain of “high” literature. He even claims that a “new paradigm of television storytelling has emerged over the past two decades, with a reconceptualization of the boundary between episodic and serial forms, a heightened degree of self-consciousness in storytelling mechanics, and demands for intensified viewer engagement focused on both diegetic pleasures and formal awareness” (“Narrative Complexity” 38-39). He argues that a third era is emerging in television—the Convergence Era—that puts viewers in control of how they watch television (through digital distribution).[17]

<20> Convergence is indeed one of the key-terms in media studies. Like the concept of transmedia storytelling, it points to the same dynamic across the whole spectrum of media culture that Mittell speaks of in the context of television. While digitization allowing for technological convergence is perhaps more broadly known (the phenomenon of Google Books being a good example here), the processes of cultural convergence of content across media platforms also have profound consequences for popular and elite practices both. Henry Jenkins is one of the primary scholars that analyze changes in the logic by which culture operates today. He argues that the emphasis today is on “the flow of content across media channels” (2). Even within one medium the liberal mixing and remixing of sources, influences, and allusions can reach staggering proportions (the practice of remix moving beyond its musical origins). In this context it is appropriate to return to the figure that informs this essay, Lady Gaga. Her music videos exhibit overwhelmingly rich intertextuality, or more, correctly, intervisuality and intermusicality. She references with great abundance (and at times with great wit) films such as Pulp Fiction, Thelma and Louise, and Metropolis, the performance style of Michael Jackson, John Travolta, and ABBA, the look of Madonna as well as that of a housewife from 1950s ads, the music from Vertigo and 2001: A Space Odyssey, myth (cf the unicorn in her Born This Way video), pop art of Andy Warhol as well as the canonized art of Salvador Dali and Francis Bacon. Lady Gaga is not of course the first to “cite” popular cultural icons (Madonna drew upon figures such as Marlene Dietrich, Marilyn Monroe, and Travolta, to name just a few). However, Gaga‘s omnivorous sampling, reiteration, and incorporation of what has been seen and heard before renders intertextuality ubiquitous rather than radical. Her re-mixing of cultural materials goes hand in hand with her media mastery. She may indeed be a prime figure of today‘s media and content convergence. Herself present on old (books or television), new (the Internet) as well as social media Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Farmville, her performances and diverse political and social statements traverse a variety of media and modes.

<21> This has prompted some critics to claim that we are “witnessing a truce in [a] longstanding conflict … between so-called elite and mass cultures” (Saler 3), sped up by the logic of convergence as a cultural shift in which “consumers are encouraged to … make connections among dispersed media content” (Jenkins 3), rather than make strong delineations between elite and masses, high art and popular forms.

<22> While the experimental techniques of literary postmodernism have percolated into mainstream culture, the “high-brow” narratives have begun to draw heavily on the aesthetic strategies of realism. In literature as well as in other art forms, the previously privileged anti-realistic aesthetics has given way to less experimental modes of story-telling. Although of course realism has never ceased to exist, it has today shifted to the centre of dominant modes of representation. Some critics regard this turn away from irony to realism as part and parcel of the new earnestness, solemnity, and seriousness that emerged after the 9/11 attacks (see Kirby 150-155). Others tend to think in terms of realism‘s cyclical reappearances, following Keith Opdahl‘s claim that “the realistic novel has remained our single major literary mode for over 125 years, habitually springing back to outlast those movements that ostensibly buried it” (1). The post-postmodern realism is not, however, a simple resuscitation of Victorian modes of representation; rather, it is a realism with an indelible impression of postmodern self-consciousness; it is an anxious or “neurotic” realism, aware that a return to the pre-postmodern modes of representation is impossible.[18] Preoccupied with the questions of trust and faith, the necessity of the communal, the emphatic expression of feelings, emotions, and affects, the importance of empathy and sharing, the post-postmodern novel may draw upon postmodern techniques since they have “come to function as ‘realistic‘ devices,” as Nicoline Timmer rightly notes (360-61), but the emphasis is on “representing the world as we all more or less share” (McLaughlin 66-7).[19] Gerhard Hoffmann too claims that the reorientation toward realism in fiction is “filtered in various ways through epistemological and aesthetic insights and artistic practices of postmodernism” (624). In an era of easy photoshopping, movies raise the stakes for what sophisticated computer graphics can do for narrative representation. From the perceptually realistic (although completely anachronistic and biotechnologically implausible) Jurassic Park (1993) through the bleak cyberpunk magic of The Matrix (1999-2003) to the phantasmagorical 3D of Avatar, realist modes of storytelling are employed with great zest. Importantly, realism as a representational mode in literature is echoed by similar tendencies in politics, religion, and other areas.

| * * * |

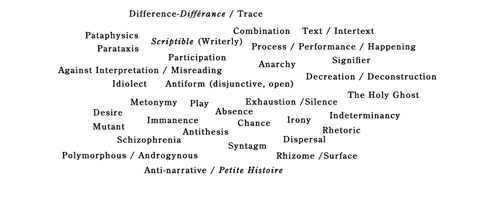

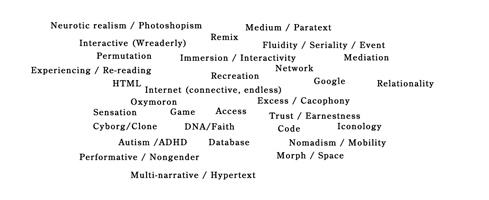

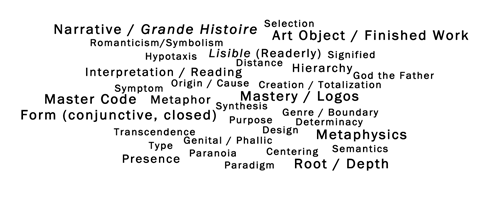

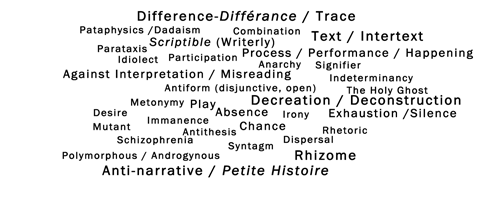

<23> In an attempt to sort out our collection of concepts, terms, and tropes that we find in the discussions about the post-postmodern we have decided to re-visit Hassan‘s intriguing chart of concepts that characterize modernism and postmodernism. We have done so in three steps. First, it seems obvious that a third column should be added to his table. What categories could be placed under post-postmodernism? Let us suggest the following:

| Modernism | Postmodernism | Post-Postmodernism |

| Romanticism / Symbolism | 'Pataphysics /Dadaism | Neurotic realism / Photoshopism |

| Form (conjunctive,closed) | Antiform (disunctive,open) | Internet (connective,endless) |

| Purpose | Play | Game |

| Design | Chance | Code |

| Hierarchy | Anarchy | Network |

| Mastery / Logos | Exhaustion / Silence | Excess / Cacophany |

| Art Object / Finished Work | Process / Performance / Happening | Fluidity / Seriality / Event |

| Distance | Participation | Immersion / Interactivity |

| Creation / Totalization | Decreation / Deconstruction | Re-creation |

| Synthesis | Antithesis | –––– |

| Presence | Absence | Access |

| Centering | Dispersal | Nomadism / Mobility |

| Genre / Boundary | Text / Intertext | Medium / Paratext |

| Semantics | Rhetoric | Iconology |

| Paradigm | Syntagm | Database |

| Hypotaxis | Parataxis | Permutation |

| Metaphor | Metonymy | Oxymoron |

| Selection | Combination | Remix |

| Root / Depth | Rhizome / Surface | Morph / Space |

| Interpretation / Reading | Against interpretation / Misreading | Experiencing / Rereading |

| Signified | Signifier | Mediation |

| Lisible (Readerly) | Scriptible (Writerly) | Interactive (Wreaderly |

| Narrative / Grande Histoire | Anti-narrative / Petite Historie | Multi-narrative / Hypertext |

| Master Code | Idiolect | HTML |

| Symptom | Desire | Sensation |

| Type | Mutant | Cyborg / Clone |

| Genital / Phallic | Polymorphous / Androgynous | Performative / Nongender |

| Paranoia | Schizophrenia | Autism / ADHD |

| Origin / Cause | Diffrence-Differance / Trace | –––– |

| God the Father | The Holy Ghost | |

| Metaphysics | Irony | Trust / Earnestness |

| Determinacy | Interderminacy | Relationality |

| Transcendence | Immanence | DNA / Faith |

At least three objections to this presentation have to be raised. First, a number of concepts that are central in the discussions about post-postmodernism cannot be paired with any of the concepts in Hassan‘s chart. Genome, bionics, long tail or ecosystems would have to be added to the right-hand column without equivalences in Hassan‘s table. So would convergence, multimodality, multimediality, and waste. Second, not all of the concepts that we list function as oppositions; Google, for instance, is of a radically different order than God the Father and the Holy Ghost. Finally, our following Hassan‘s way of presenting characteristic features of the three periods seems to encourage thinking in terms of seemingly “neat” binarisms. The binarisms of Hassan‘s two columns were reinforced by the two arrows that topped the tables: a vertical one for modernism and a horizontal for postmodernism: [20]

↕ |

↔ |

| Modernism | Postmodernism |

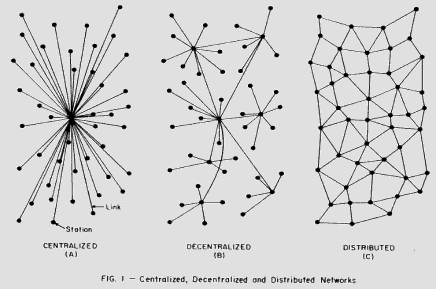

A befitting image for post-postmodernism, we think, would be the following appropriation of Paul Baran‘s visualization of the distributed communication networks:

|

This figure unsettles thinking in binary oppositions and emphasizes the importance of the Internet as a central phenomenon and force of post-postmodern culture.

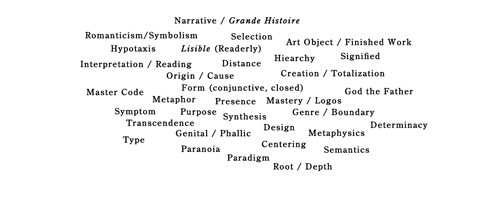

<24> That despite Hassan’s astute warnings his chart can be interpreted as advocating dichotomies is not all that surprising; after all, as Johanna Drucker rightly argues, form is constitutive of information rather than its transparent presentation (“Digital Ontologies” 144). In other words, the very look of the table bears the indelible mark of dichotomies and binarisms. To forestall the temptation of thinking in terms of binary oppositions, we propose to change the visual layout of Hassan’s chart from columns to clusters. This is thus our second intervention in his table:

| Modernism: |

|

| Postmodernism: |

|

| Post-Postmodernism: |

|

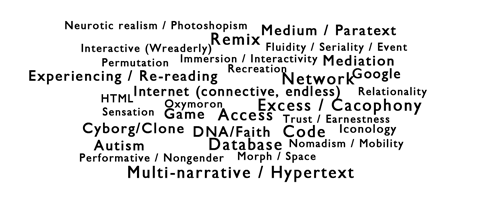

The above images secure transparency while not suggesting binary oppositions. However, we find it troubling that the images appear flat and bland; they also disturbingly imply that all the characteristics are of equal importance. So we would like to suggest a third, more radical transformation of Hassan‘s chart, this time creating tag-clouds:

| Modernism: |

|

| Postmodernism: |

|

| Post-postmodernism: |

|

<25> This way of presenting the characteristics of the three cultural paradigms appears to be disorderly, non-systematic, and messy. We have chosen different font sizes to suggest that the terms vary in their importance rather than frequency (as is otherwise common in tag-clouds). Decreasing readability somewhat, this way of visualizing the chart introduces dynamism and resonates with the post-postmodern preoccupation with images and with seeing the word as an image. However, these reconfigurations of Hassan‘s chart fail to capture what needs to be stressed over and over again: epochs and episteme do not supplant one another; their characteristics—however pronounced—cannot be sealed off from the “contaminating” (or is it enriching?) features of earlier periods.

<26> In suggesting such “messy” visualizations of cultural paradigms, we want to draw attention to a significant feature of the post-postmodern: the interrelation of access and excess, an interrelation predicated on digital technology. Immediate, uninterrupted, and universal access to virtually everything seems to be the post-postmodern object of desire, and, increasingly, our daily reality. The real and imagined ability to connect to media and information networks, or to one another, propels innovation and inventions of services and tools of technoculture. In result, the Internet both satisfies and increases our appetite for access. More and more of us access music, radio, film, and TV programs online; increasingly, we read books on a growing number of electronic devices such as the Amazon Kindle or the iPad. Open Access journals are on the rise; access to scientific articles is facilitated by such database services as MUSE or JSTOR; popular periodicals and newspapers are accessible online. Innumerable learning and teaching resources are easily found on the Internet; for example, MIT‘s OpenCourseWare program offers access to more than eighty free English language and literature courses. Crucially, the Internet offers access to the daily activities, thoughts, and desires of millions of users of Facebook, blogs or Twitter. It is tempting indeed to fall under the spell of the belief that all human knowledge and the whole world is at one‘s fingertips thanks to the Internet.

<27> But the incredibly easy access to seemingly everything creates a feeling of excess, of too much. The sites of excess may differ from critic to critic, but excess is what many critics focus on. That we live in a time of excess is indeed the argument forwarded by the French social philosopher Gilles Lipovetsky, who claims that the “post” era has been replaced by the “hyper” one in which “pretty much everywhere” we see the logic of excess, of the extreme, and of the more (33-4). Lipovetsky is not alone in regarding excess as one of the chief characteristics of our times. Bill Davidow argues that the Internet has created an “overconnectivity” that threatens to overwhelm us, and in the face of ever-present media, Jaron Lanier wants us to see people rather than their proliferating mediated selves. Johanna Drucker describes the current condition as one “of image glut and visual overstimulation” (Sweet Dreams 193). This condition of intense visual spectacle has prompted several critics to claim that the formal properties of the Baroque have infiltrated today‘s society on a grand scale (see Ndalianis and Gregg Lambert). Excess is said to be a significant feature of contemporary fiction as well. Gerhard Hoffmann, for instance, argues that one of the main legacies of postmodern fiction is “the penchant for maximalism in every form, in short, for excess” (637). According to Brian Massumi, our condition today is characterized by “a surfeit of” affect. [22] Jim Collins claims that we have moved from the shock of excess in early postmodernism to the pragmatic of excess after its end. These invocations of excess, although also encountered in discussions about postmodernism, are so common these days that excess seems to be one of the most important tropes of the post-postmodern.

| * * * |

As is probably clear to the reader of this essay, Lady Gaga, who, comet-like, advanced upon the world with her first appearance on national USA television in July 2008, seems to us to be one of the most intriguing examples of the post-postmodern excess. Her provocative, ever-changing costumes (in Telephone ranging from near-complete nudity through a catsuit to a burqa-like outfit), her theatrical writhing in music videos and on stage, her cool and calculated play with genders and sexualities (always in the plural!) may initially shock but more than anything else they provoke curiosity and hunger for more performance at an ever increasing pace. How timid Madonna seems to be in comparison to Lady Gaga, how old fashioned and restrained her world appears when compared to the David LaChapelle-like surrealist universe of Gaga!

<28> Madonna may still be going strong, but she now looks more like a relic of the old, even if she has become less playful and ironic, and thus may seem to have narrowed the gap between herself and Lady Gaga. When the two artists appeared together on the comedy show Saturday Night Live in October 2009, their staged fight seemed more serious than funny. Moreover, they looked almost identical despite the almost thirty-year difference between them. As Lady Gaga released the first single of her second full-length studio album Born This Way in February 2011, several critics noted a remarkable similarity of her song to Madonna‘s “Express Yourself” from 1989. But rather than one star mimicking another, the two songs signal a profound difference between the two stars: where Madonna emphasized the performative, Lady Gaga seems to endorse the biologism of the post-postmodern.

<29> That Lady Gaga is indeed an appropriate figure to stand for a paradigm shift is evidenced by the strong emotions and high claims that she triggers off. Merely two years after Gaga burst upon the stage, she was a cultural icon big enough to merit Camille Paglia‘s ire for her difference from Madonna. Calling Lady Gaga “the first major star of the digital age,” Paglia expressed her bewilderment at her enormous popularity: “How could a figure so calculated and artificial, so clinical and strangely antiseptic, so stripped of genuine eroticism have become the icon of her generation?” (n.p.) Paglia (like many others) sees Lady Gaga as an unworthy latter-day Madonna; instead of “Madonna‘s valiant life force,” Paglia finds in Lady Gaga “a disturbing trend towards mutilation and death.” For Judith “Jack” Halberstam, a prominent queer and gender studies expert, on the other hand, Lady Gaga stands for a positive force in today‘s culture. In the “brave new world of Gaga girliness” in Telephone, Halberstam claims, “we are watching something like the future of feminism” (qtd in Faludi 42). She calls it “Gaga pheminism” (the spelling meant to encompass the idea of phoniness) bent on dismantling the category of woman which Halberstam heartily welcomes.

<30> We read Paglia‘s generational dismay, disgust, and dismissal as well as Halberstam‘s euphoric endorsement of Lady Gaga as yet another sign of a shift in cultural sensibilities. Madonna, after all, was considered by many to be the “most visible example of what is called Post-Modernism” (Graham Cray 10; see also Georges-Claude Guilbert). Is Lady Gaga the Madonna of the Internet generation, as Kevin Gaffney proposes? Will there be courses on Lady Gaga at Princeton, Harvard, UCLA, or Rutgers as there are on Madonna? Only time will let us know the answers. At this moment what we can surely see is that as Generation Y (also known as Net Generation) is replacing Generation X, so Lady Gaga is superseding Madonna. And even if Gen X is not yet dead or the career of Madonna is yet over, we witness a proliferation of claims (not least throughout the blogosphere) that Lady Gaga be seen as a sign that postmodernism is in fact dead. This equation of Lady Gaga with the death of postmodernism, we would like to submit, is predicated on the lack of irony and self- reflective distance to her own antics. Irony and self-reflexivity, after all, are prima facie central signifying strategies in postmodernism. It is this absence of self-mockery that amplifies the feeling of excess in what Lady Gaga does. This is not to claim that there is no self-consciousness in Gaga‘s music videos or that Gaga does not make use of another aesthetic strategy of postmodernism, that of intertextuality. In fact, if anything, self-awareness is what Gaga is all about, and, as we have already shown, her music videos saturated with cross-references to pop and high culture. It is rather that Gaga‘s performances level out incongruities and discordances and thus forestall irony. A mix of indifference and aggression have replaced the postmodern playfulness, and it is in this tonal and affective difference that we want to locate Lady Gaga‘s reconfiguration of what Madonna stood for.

<31> Having charted the post-postmodern as we see it today, a number of questions emerge. What important issues and phenomena have we overlooked? Are our caveats about epochs reconfiguring each other strong enough to counter the linearity of time implied in the term “post-postmodernism”? Is post-postmodernism but a swan-song of postmodernism, a transition period or perhaps a beginning of a new epoch? While we remind ourselves that consensus on what makes up an epoch, let alone its icons, can hardly be achieved while that epoch is still going on, we begin to wonder if we may have come to the end of post-postmodernism. Is it just a coincidence that in September 2010 WIRED announced that “The Web is Dead” at the same time as Scientific American investigated our persistent need to pronounce things and ideas dead in the cover story “The End,” both magazines putting the titles of their special issues on glaringly red-colored covers? The closer we look at what is going on today, the more the picture recedes before us. And yet we beat on, stretching our minds to comprehend what surrounds us.

Endnotes

[1] And so we can read about The Self after Postmodernity (Calvin O. Schrag), Philosophy of History after Postmodernism (Ewa Domanska), Philosophy after Postmodernism (Paul Crowther), Evil after Postmodernism (Jennifer Geddes), Reclaiming Female Agency: Feminist Art History after Postmodernism (ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard), Religion after Postmodernism (Victor E. Yalor and Carl Raschke), New Media, Cultural Studies, and Critical Theory after Postmodernism (Robert Samuels). We encounter titles such as After Postmodernism: Reconstructing Ideology Critique (eds. Herbert W. Simons and Michael Billig), After Postmodernism: An Introduction to Critical Realism (eds. José López and Garry Potter), Beyond Postmodernism: Reassessments in Literature, Theory, and Culture (ed. Klaus Stierstorfer), and Do You Feel It Too? The Post-Postmodern Syndrome in American Fiction at the Turn of the Millennium (Nicoline Timmer).

[2] The chart was part of an essay originally published as “Postface 1982: Toward a Concept of Postmodernism” in the second edition of his groundbreaking book, The Dismemberment of Orpheus: Toward a Postmodern Literature (1982). It quickly became an important point of reference in discussions of postmodernism and its characteristics. Reproduced innumerable times, it is a staple feature of anthologies (for instance Norton‘s Postmodern American Fiction, edited by Paula Geyh et al), readers (see Postmodernism: A Reader, edited by Thomas Docherty), and introductions to the period (for example Simon Malpas‘s The Postmodern).

[3] See John Frow‘s argument in “What Was Postmodernism?” (22). Frow‘s claims about the concept of postmodernism is equally relevant in other cases.

[4] Hassan pondered the possible end of postmodernism in an essay “From Postmodernism to Postmodernity,” a version of which appeared in 2000. However, as early as in the late 1980s, Hassan began to focus on what may lie “beyond” postmodernism, that is, what postmodernism may be lacking (see “Beyond Postmodernism?”). At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the question mark was dropped and he more and more emphatically spoke of spirit, truth, and trust (see “Beyond Postmodernism: Toward an Aesthetic of Trust”).

[5] While all these terms are coined in a shared interest in reactions to postmodernism, they neither refer to the same set of issues nor indicate the same stance toward the new. Gans‘s “post-millenialism,” for instance, entails a rejection of the postmodern victimary thinking and a turn to “non-victimary dialogue” that will “diminish .. the amount of resentment in the world” (4). “Remodernism” refers to an attempt to introduce new spirituality into art, culture, and society to replace the cynicism of postmodernism. Kirby uses the concept of digimodernism to signal the impact of computerization on all forms of art, culture, and textuality.

[6] Nancy Partner, for instance, uses the term post-postmodernism in the title of her essay “The Linguistic Turn Along Post-Postmodern Borders: Israeli/Palestinian Narrative conflict” despite an admission that we are “well into the yet-to-be-defined post-postmodern era” (826).

[7] Wallace uses the term post-postmodernism in an essay “E Unibus Pluram” that was first published in Review of Contemporary Fiction in 1993. In the essay Wallace discusses the impact of television on American fiction.

[8] Best and Kellner rightly note that “as we enter the Third Millennium we are in the midst of a tempestuous period of transition propelled principally by transmutations in science, technology, and capitalism” (Postmodern Adventure 6).

[9] The concept of technoculture was first introduced by Penley and Ross in 1991. They use it interchangeably with the phrase “cultural technologies.” The term has been appropriated by other critics, its meaning adjusted to other purposes.

[10] We appropriate Franco Moretti‘s concept of “distant reading” to indicate that we base our observations on our analyses of other critics‘ statements.

[11] Cf. for instance titles such as Return to Reason (Stephen Toulmin), or Return to Common Sense, three books so titled by three authors (Michael Waldman, John Ikerd, Thomas Mullen).

[12] See for example History of Beauty (ed. Umberto Eco), Close Reading (eds. Frank Lentricchia and Andrew Debois), and How to Read a Poem (Terry Eagleton).

[13] See for instance Bauman‘s Liquid Times.

[14] See for instance the following for the range of interests in this area: A Sense of Things: The Object Matter of American Literature (Bill Brown), Wild Things: The Material Culture of Everyday Life (Judy Attfield), Material Thinking (Paul Carter), and The Comfort of Things (Daniel Miller).

[15] We follow here Hillary Chute and Marianne DeKoven‘s proposition that “graphic narrative” be used to refer to all “narrative work in the medium of comics” (767).

[16] It needs to be noted, however, that the Franco-Belgian tradition is markedly different from the Anglo-American one in its long-standing serious investigation on comics.

[17] The other two eras, according to Mittell, are the Classic Network Era (1940s to mid 1980s), and the Multi-Channel Era (the 1980s) (see Television and American Culture).

[18] The term “neurotic realism” was coined by Charles Saatchi to refer to a new trend in British visual art that was shown in a two-part exhibition 1998-1999.

[19] For Timmer‘s list of the characteristics of the post-postmodern novel, based on her close readings of the work of David Foster Wallace, Dave Eggers, and Mark Danielewski, see 359-61. Robert L. McLaughlin too discusses the fiction of David Foster Wallace, but he puts him in the company of Jonathan Franzen.

[20] Of course Hassan is too astute and self-conscious a critic to think in terms of easy polarities. He embeds his chart in an essay that time and time again stresses the contingency, tentativeness, and conditionality of his propositions. Yet it is easy to ignore the cautiousness of his rhetoric of “should,” “may,” and “perhaps” and the generally speculative tone of his investigation of which the chart is a part. It is easy too to disregard his caveat that “the dichotomies this table represents remain insecure, equivocal. For differences shift, defer, even collapse; concepts in any one vertical column are not all equivalent; and inversions and exceptions, in both modernism and postmodernism, abound” (“Toward” 92; emphasis added).

[21] Baran‘s figure of the distributed network is of course related to his seminal work on packet switching technology, which is an important foundation of the Internet.

[22] Few would have predicted that affects, emotions, and feelings would be subjected to vigorous investigations in the decade following one of the most influential statements about the postmodern condition, Jameson‘s argument about the “waning of affect” (Postmodernism 10).

Work Cited

Attfield, Judith. Wild Things: The Material Culture of Everyday Life. Oxford: Berg, 2000.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge: Polity, 2010.

Baran, Paul. On Distributed Communications: Introduction to Distributed Communications Networks. United States Air Force Project RAND. Memorandum RM-3420-PR. August 1964.

Best, Steven and Douglas Kellner. The Postmodern Adventure: Science, Technology, and Cultural Studies at the Third Millennium. London: Routledge, 2001.

---. The Postmodern Turn. New York: Guilford P, 1997.

Bolter, Jay David. Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. 2nd edition. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2001.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. “Altermodern Manifesto.” http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/altermodern/manifesto.shtm

--- . Relational Aesthetics. Trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods with Mathieu Copeland. N.p.: Les presses du réel, 2002.

Brown, Bill. “Introduction: Textual Materialism.” PMLA 125.1 (January 2010): 24-28.

--- . A Sense of Things: The Object Matter of American Literature. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2004.

Carter, Paul. Material Thinking. Melbourne: Melbourne UP, 2004.

Chandler, James. “Introduction: Doctrines, Disciplines, Discourses, Departments.” Critical Inquiry 35 (Summer 2009): 729-46.

Chute, Hillary and Marianne DeKoven. “Introduction: Graphic Narrative.” Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (2006): 767-782.

Collins, Jim. Architectures of Excess: Cultural Life in the Information Age. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Coover, Robert. “The End of Books.” New York Times Book Review 21 June 1992: 1, 23-25.

Cray, Graham. “Post-modernist Madonna.” Third Way 14.6 (1991): 7-10.

Crowther, Paul. “Introduction: Postmodernity, Perspectivalism and Supermodernism.” Philosophy after Postmodernism: Civilized Values and the Scope of Knowledge. London: Routledge, 2003. 1-3.

Davidow, William H. Overconnected: The Promise and Threat of the Internet. Harrison, NY: Delphinium, 2011.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Trans. Eric Prenowitz. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1996.

Docherty, Thomas, ed. Postmodernism: A Reader. New York: Columbia UP, 1992.

Drucker, Johanna. “Digital Ontologies: The Ideality of Form in/and Code Storage—or—Can Graphesis Challenge Mathesis?” Leonardo 34.2 (2001):

--- . Sweet Dreams: Contemporary Art and Complicity. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2005.

--- and Emily McVarish. Graphic Design History: A Critical Guide. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2009.

Eagleton, Terry. After Theory. London: Penguin, 2003.

--- . How to Read a Poem. Oxford: Blackwell, 2007.

Eco, Umberto, ed. History of Beauty. Trans. Alastair McEwan. New York: Rizzoli, 2004.

Eshelman, Raoul. Performatism or The End of Postmodernism. Aurora, Colorado: Davis Group Publishers, 2008.

Evans, Katherine. The Stuckists: The First Remodernist Art Group. London: Victoria Press, 2000.

Faludi, Susan. “American Electra: Feminism‘s Ritual Matricide.” Harper‘s. October 2010: 29-42.

Foster, Hal. The Return of the Real. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996.

Frow, John. “What Was Postmodernism?” Time and Commodity Culture: Essays in Cultural Theory and Postmodernity.” Oxford: Clarendon P, 1997. 13-63.

Gaffney, Kevin. “The Lady Gagag Saga.” MA thesis. Royal College of Art. 2010.

Gaga, Lady. Telephone. Dir. Jonas Åkerlund. 2009. http://www.casttv.com/video/tmi2f7/lady-gaga-telephone-ft-beyonc-video

Gaga, Lady. Born This Way. Dir. Nick Knight. 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wV1FrqwZyKw

Gans, Eric. “The Post-Millenial Age.” Anthropoetics 209. 3 June 2000. http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/views/vw209.htm

Geyh, Paula, Fred G. Leebron, and Andrew Levy, eds. Postmodern American Fiction: A Norton Anthology. New York: Norton, 1998.

Guilbert, Georges-Claude. “Madonna as Postmodern Myth: How One Star‘s Self-Construction Rewrites Sex, Gender, Hollywood and the American Dream.” Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002.

Habermas, Jürgen et al. An Awareness of What Is Missing: Faith and Reason in a Post-secular Society. Trans. Ciaran Cronin. Cambridge: Polity, 2010.

Halberstam, Judith Jack. “Calling All Angels: Phony Femininities in the Age of Gaga.” No Longer in Exile: The Legacy and Future of Gender Studies. Conference. The New School, New York University. Theresa Lang Center, New York. 27 March 2010. Lecture.

Hassan, Ihab. “Beyond Postmodernism? Theory, Sense, and Pragmatism.” 1989. Rpt. in Rumors of Change: Essays of Five Decades. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 1995. 126-138.

--- . “Beyond Postmodernism: Toward an Aesthetic of Trust.” Beyond Postmodernism: Reassessments in Literature, Theory, and Culture. Ed. Klaus Stierstorfer. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003.199-212.

--- . “From Postmodernism to Postmodernity: The Local/Global Context.” N.d. http://www.ihabhassan.com/postmodernism_to_postmodernity.htm

Hassan, Ihab. “Postface 1982: Toward a Concept of Postmodernism.” Rpt. in The Postmodern Turn: Essays in Postmodern Theory and Culture. Athens: Ohio UP. 1987. 84-96.

Heer, Jeet, and Kent Worcester. Introduction. A Comic Studies Reader. Ed. Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2009. xi-xv.

Heise, Ursula K. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global. New York: Oxford UP, 2008.

Hoffmann, Gerhard. From Modernism to Postmodernism: Concepts and Strategies of Postmodern American Fiction. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2005.

Hutcheon, Linda. The Politics of Postmodernism. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Ikerd, John. Return to Common Sense. Flourtown: R.T. Edwards, 2007.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke UP, 1991.

Jencks, Charles. Critical Modernism. Where is Post-Modernism Going? 5th ed. London: Wiley Academy, 2007.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York and London: New York UP, 2006.

Kirby, Alan. “The Death of Postmodernism.” Philosophy Now 58 (2006) http://www.philosophynow.org. Accessed 13 March 2010.

Kirby, Alan. Digimodernism: How New Technologies Dismantle the Postmodern and Reconfigure our Culture. New York: Continuum, 2009.

Lambert, Gregg. The Return of the Baroque: Art, Theory, and Culture in the Modern Age. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Landow, George. Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1991.

Lenier, Jaron. You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto. New York, NY: Vintage, 2010.

Lentricchia, Frank and Andrew DuBois, eds. Close Reading: The Reader. Durham: Duke UP, 2003.

Lipovetsky, Gilles. With Sébastian Charles. Hypermodern Times. Trans. Andrew Brown. Cambridge: Polity, 2005.

Lopez, José and Garry Potter, eds. After Postmodernism: An Introduction to Critical Realism. New York: Athlone, 2001.

Malpas, Simon. The Postmodern. London: Routledge, 2005.

Manovich, Lev. “The Practice of Everyday (Media) Life: From Mass Consumption to Mass Cultural Production?” Critical Inquiry 35.2 (2009): 319-331.

Massumi, Brian. Parables for the Virtual. Durham: Duke UP, 2002.

McGann, Jerome. Radiant Textuality: Literature after the World Wide Web. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

McHale, Brian. “What Was Postmodernism?” Electronic Book Review 20 Dec. 2007. http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/fictionspresent/tense

McLaughlin, Robert L. “Post-Postmodern Discontent: contemporary Fiction and the Social World.” Symploke 12.1-2 (2004): 53-68. MUSE accessed 20 April 2011.

Miller, Daniel. The Comfort of Things Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2008.

Miller, J. Hillis. Illustration. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1992.

Mitchell, W.J.T. “The Pictorial Turn.” Artforum. March 1992: 89-94.

Mitchell, W.J.T. and Mark N.B. Hansen. Introduction. Critical Terms for Media Studies. Eds. Mitchell, W.J.T. and Mark N.B. Hansen. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2010. vii-xxii.

Mittell, Jason. “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television.” The Velvet Light Trap 58 (2006): 29-40.

Mittell, Jason. Television and American Culture. New York: Oxford UP, 2009.

Moraru, Christian. Cosmodernism: American Narrative, Late Globalization, and the New Cultural Imaginary. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2011.

Moretti, Franco. “Conjectures on World Literature.” New Left Review 1 (Jan.-Feb. 2000): 54-68.

Mullen, Thomas. Return to Common Sense. N.p.: Thomas Mullen, 2009.

Ndalianis, Angela. Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2004.

Nelson, Robin. “Analyzing TV Fiction. How to Study Television Drama.” Tele-Visions: An Introduction to Studying Television. Ed. Glen Creeber. London: British Film Institute, 2006. 74-86.

Opdahl, Keith. “The Nine Lives of Realism.” Contemporary American Fiction. Eds. Malcolm Bradbury and Sigmund Ro. London: Edward Arnold, 1987. 1-16.

Paglia, Camille. “Lady Gaga and the Death of Sex.” The Sunday Times 12 September 2010. Web. Accessed 20 April 2011.

Parry, Marc. “The Humanities Go Google.” Chronicle of Higher Education 28 May 2010. http://chronicle.com/article/The-Humanities-Go-Google/65713/

Partner, Nancy. “The Linguistic Turn Along Post-Postmodern Borders: Israeli/Palestinian Narrative Conflict.” New Literary History 39.4 (Autumn 2008): 823-845. MUSE accessed 20 April 2011.

Penley, Constance, and Andrew Ross. Technoculture. Minnesota: U of Minnesota P, 1991.

Rimmon-Kenan, Shlomith. A Glance Beyond Doubt: Narration, Representation, Subjectivity. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1996.

Saler, Michael. “Comic Turns: From Book-Burning and Prohibition to Pulitzer Prizes and Prestige; The Cultural Triumph of the ‘Graphic Novel.‘” Rev. of The Ten-Cent Plague by David Hajdu and Maps and Legends by Michael Chabon. TLS 6 June 2008: 3-5.

Samuels, Robert. New Media, Cultural Studies, and Critical Theory after Postmodernism: Automodernity from Zizek to Laclau. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Timmer, Nicoline. Do You Feel It Too? The Post-Postmodern Syndrome in American Fiction at the Turn of the Millennium. Postmodern Studies 44. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2010.

Toulmin, Stephen. Return to Reason. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 2001.

Turner, Tom. City as Landscape: A Post-Postmodern View of Design and Planning. London: Taylor & Francis, 1996.

Vermeulen, Timotheus, and Robin van den Akker. “Notes on Metamodernism.” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture 2 (2010) n. pag. Web Accessed 1 March 2011.

Waldman, Michael. Return to Common Sense: Seven Bold Ways to Revitalize Democracy. Naperville: Sourcebooks, 2008.

Wallace, David Foster. “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction.” A Supposedly Fun Thing I‘ll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1997. 21-82.

Wills, John E., Jr. “The Post-Postmodern University.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 27.2 (1995): 59-62.

Return to Top»