Reconstruction Vol. 14, No. 3

Return to Contents»

How to Do Narratives with Maps: Cartography as a Performative Act in Gulliver's Travels and Through the Looking-Glass / Emmanuelle Peraldo and Yann Calbérac

<1> The articulation between literary text and space has been significantly redefined thanks to two major theoretical turns. Because of the spatial turn that marked the humanities and social sciences from the 1980s onwards, time - inherited from the Enlightenment's ideal of progress - is not the main category of analysis any longer: space has replaced it (Soja, 1989). The spatial dimension of objects is now at the core of critical and analytical preoccupations: all fields of knowledge (and not only geography) are now invited to reconsider space, places and mapping. Literary studies reflect this paradigmatic shift as can be seen in the increased usage of spatial vocabulary in critical texts to decipher the way narratives are built. As a parallel to this epistemological revolution, the beginning of the 1980s saw a cultural turn which questionned the positivist approach by focusing on culture, i.e. circumstances which constitute the specificity of human beings. All disciplines have been suggested to take into account representations and discourses: texts, including literary ones as those of Swift and Carroll, have become a legitimate object for both the social sciences and geography. The spatial and cultural turns have thus caused a deep transformation of the academic landscape: objects themselves receive more attention than disciplinary methods. Current gender, urban or cultural studies departments exemplify these changes in theoretical approach as they gather researchers coming from literature, history, anthropology, to name several examples. As encapsulated in the following quotation by Robert T. Tally Jr., "literary cartography, literary geography, and geocriticism enable productive ways of thinking about the issues of space, place, and mapping after the spatial turn in literary and cultural studies" (Tally, 2013: 3). The spatial dimension of literary narratives has become an autonomous field of research, at the junction of literature and geography. That said, this field is comprised of a number of various approaches determined by the disciplinary background of those who explore it: even if they work on the same object, literary critics and geographers differ in their methods. The former focus on the poetic dimension of space while the latter question the spatiality of narratives.

<2> Today, the major development for literary critics to tackle the poetic dimension of space is owed to Bertrand Westphal and his translator Robert T. Tally Jr. Wesphal proposes the concept of geocriticism to define the interdisciplinary method of literary analysis that consists in using geographical space as a tool and it is defined by Bertrand Westphal in La Géocritique. Réel, fiction, espace: "It is the role of geocriticism to invest (partially) and to structure (a little) the crossroads between the different arts using material reality and space and time markers so as to get an aesthetic representation of it." [1] The huge success of Westphal's theory has clouded other fruitful approaches like Kenneth White's geopoetics. [2] The renewal brought by these approaches lies on several objects such as landscape (Collot, 2005) environment (ecocritics such as Buell) and maps (literary cartography, a good example of which is Robert Clark and Benjamin Pauley's mappingwriting project). Barbara Piatti also worked extensively on literary cartography, as in The Literary Atlas of Europe. These renewing approaches have fullfilled Franco Moretti's radical project to diversify and renew literary approaches thanks to spatial and natural sciences, as promoted in the title of his book: Graphs, Maps, Trees (2005).

<3> For geographers who have taken the cultural turn, literature is a relevant source for enhancing the way people are connected to the world. From the moment of this paradigm shift, a literary geography started to rise (Mallory and Simpson-Housley, 1987; Pocock, 1988; Noble and Dhussa, 1990; Lando, 1996), whose purpose was to decipher various objects such as travel narratives or landscapes (Chevalier, 1992; Tissier, 1995; Brosseau, 1996; Madœuf & Cattedra, 2012). Mapping fictional spaces has become the major issue of this movement. This interest in writing is due to a return to the etymology of the word geography, i.e. the writing (graphein) of the Earth.

<4> Now that the background is set, we would like to present the object in which we are particularly interested: maps embedded in fictional narratives - Christina Ljunberg has already demonstrated the importance of maps in revealing the interrelations between verbal and visual media in fictional texts (Ljunberg, 2012). So have Pristnall and Cooper in The Cartographic Journal (2011). Our contention is that the presence of those very maps makes us realise the incapacity of a sequential text to take into account space, which has no beginning, no ending and no chapters. That has already been made clear by Perec's disappointing "attempt at exhausting a place in Paris" (Perec, [1975], 2010) insofar as he never succeeds in totally describing the Place Saint-Sulpice. A solution could be proposed to compensate for the shortcomings of the text by completing it with a specific language, which has been developed to "tell" space: cartography. After all, a map is indeed "a representation founded on a language whose characteristic is to build the analogical image of a place" (Lévy, 2003: 128).

<5> To test this hypothesis, we have decided to analyse the embedded maps of Gulliver's Travel by Jonathan Swift (1726) and Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll (1871). First, both belong to the travel narrative genre, as their complete titles - Lemuel Gulliver's Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There - reveal with words such as "travels", "remote", "through" or "there", and as both depict the heroes' confrontation with a radical otherness. Secondly, those texts negotiate differently their relation to the real: Gulliver's Travels, as a typical 18th-century text, is fictional but pretends not to be, repeating its truth claims that were necessary to avoid censorship (Peraldo, 2010), whereas Alice is a fiction which keeps claiming its fictionality, even if both texts use elements of the fantastic and the marvellous (Todorov, 1970). Thirdly, Swift and Carroll use a process which articulates text and liminal maps. In Gulliver, Swift reproduces the authentic maps of the great cartographer of the time, Herman Moll, but he falsifies them by adding in the blanks of the maps the imaginary islands to which Gulliver goes (Bracher, 1944; Reinhartz, 1997) (fig. 1). In Alice, instead of a map, the reader finds a chessboard that can be considered as a map, according to Lawrence Gasquet, who insists on the visual and graphic quality of Carroll's writing and emphasizes the role of the visual representation as a topographical tool for representing thought. For Gasquet, the chessboard thus functions as a map in that it is part of the topographical language of Carroll's text, and because it duplicates the world on a smaller scale, which is the aim of a cartographic image (Gasquet, 2000) (fig. 2).

<6> Those maps can best be scrutinized thanks to cartography. Maps are made of various signs that allow a semiotic reading of them (Bertin, 1960): they constitute a specific and autonomous language. Therefore, as they are a form of language, and as performativity is a property of every language (Austin, 1962), we argue that those maps embedded in fictional narratives can be deciphered thanks to this coupling of semiotics and pragmatics. As for all maps, those which are included in novels obey semiotic rules which reflect the condition and period of their production. Hence, the performative turn invites us to take into account the performativity of cartographic language. If per Austin's theory it is now possible "to do things with words", it can then be posited that it must be possible to do things with maps, and to act on the diegesis and characters due to the cartographic device. To test this reading grid (semiotics / pragmatics), our methodology is informed by the cross-fertilization of the two disciplines we belong to: this paper is co-written by a specialist of British literature and a geographer specializing in the epistemology of geography. This analysis is the first stage of a collaboration that questions the spatial dimensions of literary texts, according to two different academic traditions that we wish to cross-fertilize: literary critics focus on the poetic dimension of space while geographers question the spatiality of narratives.

<7> The two kinds of maps that are to be found in Swift and Carroll tend to cloud referentiality insofar as they invite their readers to go beyond the Manichean opposition between true and false, which is constitutive of fictions: even if these maps are not topographically exact (i.e. neither Gulliver's islands nor Alice's land exist in reality), they are fictionally true. They do not enable readers to actually find these locations on the Earth, but they help them find their ways in the worlds of words created by the two authors. The endeavour is to go beyond the simple referentiality of maps to study the referentiality constructed by maps within texts: the meanings of maps depend on the way they are practiced by either novel-readers or map-users. These various practices define the functions of maps and invite us to focus on their peculiar statuses and to answer this crucial question: what is a map? Our argument is that maps are parts of the novels' meaning processes that the reader has to decipher, as it is a graphic and figurative inscription, which combines its specific language, a semiotics, its uses and its functions (Lévy, 2003).

<8> The stakes of Swift and Carroll's maps appear: are these maps real maps, according to the above-mentioned definition? To answer this question, it might be essential to ponder the referentiality of the maps in the narratives in which they are inserted. What do these maps describe? What functions do they have in the meaning process? This opposition between what is said and what is produced echoes the distinction identified by J. L. Austin (Austin, 1962; Mondada, 2003) between stating utterances (which describe reality) and performative utterances (which transform reality), which is mirrored in literary studies by the famous opposition between mimesis (imitation) and poesis (creation of images). To what extent is it relevant to apply Austin's performativity to Swift and Carroll's maps? Are there such things as "cartographic acts" (Shusterman, 2000) similar to Austin's "speech acts"? These questions lead us to first explore the way maps can fill in the silences of the texts in order to solve the problem of referentiality. The second part of the analysis will tackle the pragmatic and performative role of maps within the writing process. The ambition of this paper is double: for the literary critic, the aim of reading extra-narrative objects such as maps is to question the textuality and literariness of external objects - such as maps - embedded in literary texts; for the geographer, these two maps reveal the opposition between space considered as a position and space defined as an interaction.

<9> The maps under scrutiny here question the texts in which they are inserted on two different levels. First, they raise the question of textuality by interrogating the way these two travel narratives are made by maps as well as words. Secondly, they enable readers to locate the stories they are told, and referentiality anchors them in the realistic horizon. We want to start by focusing on semiotics and the "stating" dimension of maps i.e. their mimetic function. Even if places are fictitious, their cartographic representations aim at increasing their "referential fallacy" (Riffaterre, 1982) by playing the part of a "reality effect" (Barthes, 1982).

<10> One of the specificities of Gulliver's Travels is that from the very first edition of the text, maps have systematically illustrated Swift's work. In his fourth edition of Robinson Crusoe (London: W. Taylor, 1719), Defoe (or his publisher) also inserted a map supposedly drawn by Woodes Rogers map (fig. 4), and even gave the latitude of the island upon which Crusoe was stranded - a latitude which was off by two degrees, reflecting either the mistakes of maps at a time when cartography was not as accurate as today, or his own poetic license in writing a story that was partly historical, partly fictional. In order to make readers believe in the reality of the events narrated, Swift and Defoe obeyed the rules of the travel account, including for instance the use of maps. As Percy G. Adams says, "the 'récit de voyage' cannot be a literary genre with a fixed definition" (Adams, 1983, 282). Indeed, it is a polymorphous genre or mode of writing, but among the major common points of travel narratives, there is the fact that the travel narrative relies and depends on the actual travelling experience it recounts; it is a means of interrogating the relationship between the self and the world, and very often it is deployed to question the known from the observation of the unknown; and it must also be useful : its aim is both to entertain and to instruct (Magetti, 2004). And indeed, in Swift's time, being real was the imperative condition for being published. In an endeavor to meet these requirements for realism, the author borrowed his maps from Herman Moll, who was the most famous 18th-century English cartographer, [3] and who revolutionized the cartographic practices by breaking with conventions which consisted of, for example, adorning maps with monsters or marvellous creatures so as to fill in blank spaces on maps.

<11> Bracher has analysed the history of the maps of Gulliver's Travels. He pointed out that these maps had been taken from Herman Moll but had been modified so as to highlight the places to which Gulliver travelled:

He had the text of the book to give approximate locations of the mythical countries, but these could only be approximate, since swift's directions are confused and inconsistent. On each map, he tried to frame the ocean surrounding Swift's mythical land with an authentic coast line copied from Moll. For the map of Brobdingnag, following Swift's hint that the peninsula was joined to America, his authentic frame is the Californian coast. (Bracher, 1944: 62).

The presence of these maps is owed to a publisher, and Swift accepted the idea to the point that he encouraged their publication in the successive editions of his work.

<12> Moreover, these maps anchor the text in a geographical perspective, which is reinforced by the various semantic fields. Indeed, Gulliver's Travels is loaded with toponyms, geographic locations, and nautical terms. For example, the first letter of the first book starts with two pages accumulating real toponyms - Nottinghamshire, Cambridge, Emanuel-College, London, Leyden, Holland (p. 5), East and West Indies, Wapping, Bristol, Van Diemen's land (p. 6) - making readers forget that Lilliput, the place name which appears on page 7, is imaginary. These toponyms are completed with their accurate geographic positions and the nautical vocabulary turns this narrative into what could be Gulliver's logbook:

We had a very prosperous gale, till we arrived at the Cape of Good Hope(…) We then set sail, and had a good voyage till we passed the Straits of Madagascar; but having got northward of that island, and to about five degrees south latitude, the winds, which in those seas are observed to blow a constant equal gale between the north and west (…) during which time, we were driven a little to the east of the Molucca Islands, and about three degrees northward of the line (…)

Finding it was likely to overblow, we took in our sprit-sail, and stood by to hand the fore-sail; but making foul weather, we looked the guns were all fast, and handed the mizen. The ship lay very broad off, so we thought it better spooning before the sea, than trying or hulling. We reefed the fore-sail and set him, and hauled at the fore-sheet; the helm was hard a-weather. The ship wore bravely. We belayed the fore down-haul; but the sail was split, and we hauled down the yard, and got the sail into the ship, and unbound all the things clear of it. (Swift, 71-72, our emphasis)

This abundance of minute details un-places readers more than it helps them orient themselves. Hence, it questions the generic horizon to which Gulliver's Travels belongs, and it echoes a literary heritage, which was reactivated by the publication of Thomas More's Utopia in 1516: are the islands visited by Gulliver utopic places? If one considers the utopia as a perfect place (eu-topia), then Lilliput, Brobdingnag, and so on can absolutely not be considered as examples of those places, insofar as they are part of a satiric intention which assimilates them to dystopia more than utopia. But this term works if one refers to the second meaning of the term utopia, a place which does not exist ( ou-topia). The geographical enumerations and the maps have the same function: to convince the reader that this utopia is real, and all the signs concur to create that reality effect.

<13> The use of maps anchors Gulliver's Travels in the advent of modernity since it organises the world by organising knowledge and vice versa. The chorographic process (through a regional exploration of the world, bit by bit) refers to the analytical position which was developped extensively at that time. On the one hand, maps enrich that semantic field and aim at organising these descriptions by localising them on maps. However those maps have been tampered with and the territories they represent have no real existence. Nevertheless, the fake maps, by offering a cartographic representation, give those imaginary territories an existence. Maps thus have the same functions as descriptions. On the other hand, the narrative is organised around an observer who garantees the scientificity of the ethnographic endeavour: the comparison with what readers are familiar with - "a squale you might have heard from Londonbridge to Chelsea" (p. 79) - increases the reality effect. Swift even refers to his contemporary geographers and offers to correct their maps, which he considers misleading:

The whole extent of this prince's dominions reaches about six thousand miles in length, and from three to five in breadth: whence I cannot but conclude, that our geographers of Europe are in a great error, by supposing nothing but sea between Japan and California; for it was ever my opinion, that there must be a balance of earth to counterpoise the great continent of Tartary; and therefore they ought to correct their maps and charts, by joining this vast tract of land to the north- west parts of America, wherein I shall be ready to lend them my assistance (Swift, 99).

<14> This specificity can also be found in the very first pages of Through The Looking-Glass, which offers a dramatis personae completed with a chess problem, [4] which can be considered as a map according to Lawrence Gasquet: "Through the Looking-Glass represents Alice's peregrinations on the chessboard; Can there be a better map than a two-coloured chessboard? It can be noticed that Carroll is careful to use it in the liminal page of his second tale, as a clear and practical visual landmark to be consulted by readers whenever they need to." (Gasquet, 2000: 100). [5] This map is completed by the evocation of landscape that Alice describes from the top of a hill:

[Alice and the Queen] walked on in silence till they got to the top of the little hill. For some minutes Alice stood without speaking, looking out in all directions over the country - and a most curious country it was. There were a number of tiny little brooks running straight across it from side to side, and the ground between was divided up into squares by a number of little green hedges, that reached from brook to brook. (Carroll, 125, our emphasis).

In this Robinson Crusoe-like inaugural act, Alice - according to a classical geographical position (Calbérac, 2010) - climbs at the top of a hill in order to appropriate by her gaze what will become her territory: her looking-from-above domination is at the same time symbolic and political, as she ends up becoming the queen of this country. As a perfect positivist geographer, she describes the brooks, the hedges (reminiscent of the debate on enclosures in the eighteenth-century Britain), which were a common feature of the British countryside as painted for example by Constable (Fig. 5). The polysemy of the word "country" invites readers to mentally turn this countryside landscape into a realm, which metonymically speaking, becomes a whole and closed universe, similar to what Paul Claudel created by writing in the very first stage direction of Paul Claudel's Satin Slipper (1931): "The scene of this drama is the world". Alice goes on:

'I declare it's marked out just like a large chessboard!' Alice said at last. 'There ought to be some men moving about somewhere - and so there are!' She added in a tone of delight, and her heart began to beat quick with excitement as she went on. 'It's a great huge game of chess that's being played - all over the world - if this IS the world at all, you know. Oh, what fun it is! How I wish I was one of them! I wouldn't mind being a Pawn, if only I might join - though of course I should like to be a Queen, best.'" (Carroll, 125, our emphasis).

The landscape she observes before walking through it does not only look like a chessboard: it really is one, with its pawns and squares, and it is actually present in the text in the form of the chessboard-landscape drawn by Tenniel (fig. 3). [6] Hence, this space is now regulated by the chess-pawns' moving rules, and Alice's will appears: she wants to become a queen by reaching the last line of the chessboard. By doing this, she fulfills the dream of explorers who usually want to get to the end of the world and dominate it. As nonsensical as it may appear, the liminal chessboard is indeed an efficient map not only for readers to follow Alice's adventures, but also for Alice herself to find her way in this Looking-Glass country and to understand its rules.

<15> The map in Carroll is not to be read on the same level as in Swift. This map is not drawn according to a scale. The liminal chessboard and the chessboard-landscape that Alice describes from the top of the hill are one and the same. The map is no longer a reduced representation of reality: they are two ways of representating the same thing. However, this map helps the reader understand Alice's displacements without using the usual geographic and cartographic tools, such as orientation, topography and toponymy, as employed in Gulliver's Travels. This enclosed universe relying on radical alterity could belong to Michel Foucault's heterotopia, i.e. spaces of otherness, in which the example of the looking-glass is appropriated by Foucault:

Because these places are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about, I shall call them, by way of contrast to utopias, heterotopias. I believe that between utopias and these quite other sites, these heterotopias, there might be a sort of mixed, joint experience, which would be the mirror. The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface; I am over there, there where I am not, a sort of shadow that gives my own visibility to myself, that enables me to see myself there where I am absent: such is the utopia of the mirror. But it is also a heterotopia in so far as the mirror does exist in reality, where it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position that I occupy. From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see myself over there. [7]

More than a mere reality effect, the materiality of maps (Moll's fake maps and the real chessboard-map) is the key to imagination. Confronted by these maps, readers are in the same posture as Alice in front of the mirror: as Alice pretends she can overcome its materiality by getting through it, readers are invited to conquer the materiality of the maps drawn on the pages in order to reach imaginary regions such as Lilliput or the Looking-Glass country. Readers need to go beyond the semiotic dimension of these maps, hence discovering the active role they play in the economy of the literary texts.

<16> Let's now explore the imaginary dimension of maps keeping in mind what Philippe Vasset explains at the beginning of his Livre blanc : "I started to be interested in maps when I understood that they had only remote connections with reality" (2007: 9). [8] The pragmatic, poetic and performative functions of these maps should be examined, as Alice invites us: "'I declare it's marked out just like a large chessboard!' (…) if this IS the world at all, you know." (Carroll: 125, our emphasis). By naming the chessboard with language, she makes it real and gives new rules to the place she evolves in: the chess rules. Our contention here is that these maps do not only produce narratives, i.e. action or drama, but it is within these maps - what they either show or hide - that narratives originate and develop. As Austin wondered "how to do things with words", we ask: "how to do narratives with maps?" To solve this question, we have to change our way of reading these two works. As Gulliver and the explorers he stands for have attempted to fill in the blanks of maps, we are going to focus on the blanks of texts and look for answers in between the lines.

<17> Vasset's 21st-century inquiry into what is hidden in the blank spaces of the map is actually a reiteration of one of the questions which underwent a crucial turn in the modern era. At that time, a gap appeared between positive knowledge and imaginary knowledge: this mixture characterized the remerging modernity, and was at the origin of the distinction between science and literature (Aït-Touati, 2011). On the one hand, this thirst to discover the world - made possible by technical progress - led to a better understanding of the world, in which geography and cartography contributed to bring order. Cartographer Herman Moll was emblematic of this distinction: he refused to fill in the blanks of his maps with the usual monsters, and the terrae incognitae remained empty. On the other hand, imagination was being rejected from scientific discourse. According to Pasquali (1994), travel narratives made contact with alterity possible, but when it was not possible, literature was there to help. Hence, literature - thanks to its poetic function - created places whose only existence were in the author's mind. It was precisely in those blanks that Swift made up the imaginary places Gulliver described: narratives obeyed a thirst for knowledge. [9]

<18> By using Herman Moll's maps, Swift revealed a positional function of maps that presented the precise location of Gulliver's adventures that the reader was to discover. Indeed, each book opens with a map covered with topographic and toponymic elements, but no mention is made of the action's unfolding. These empty maps are to be completed by the narration which occurs just after the liminal maps: this will to fill in the gaps of the map turns them into performatively creative narratives. It is therefore not surprising, as has been shown above, that each book should start with a letter saturated with geographical terms and toponyms: Swift's ambition is to articulate maps and text. But as mentioned before, when the map orders, the narrative disorders.

<19> Nothing like that occurs in Through the Looking-Glass: the map is of another nature and the mapping process is more complex. The chessboard map does not mix reality and imagination; it is pure imagination, and the map does not aim at localizing any place. That is why this map is made of a game, which is the climax of the imaginary (Caillois, 1958). Carroll's fiction unfolds in a purely imaginary place - even conceptual, as the chessboard suggests - ruled by a language that opens myriad possibilities (as numerous as the moves in a game of chess) thanks to the magical sesame, "let's pretend", that enables Alice to go through the looking-glass. It is therefore a reflection on language that readers are invited to, as Deleuze suggested by theorizing on being and becoming in his developments on Alice in The Logic of Sense (Deleuze, 1969). There is a perfect adequacy between the liminal chessboard and the world Alice goes through, but still the chessboard is not the mere representation of that world, even if the fields and hedges that Alice describes look like the chessboard. The latter is not so much the framework of the action as what makes it possible: the characters (the players) move according to the rules of the game and the structure of the chessboard. Conversely, once they have accepted the rules, the players can operate freely and reveal the multitude of possibilities of the moves. Space is at the same time what makes possible and what is made possible by the practices of the players (Lussault, 2007).

<20> In the first editions of the text, Lewis Carroll completed this map with a highly pragmatic dramatis personae, i.e. literally the list of the characters of the drama. Indeed, Carroll combines that list of characters with a chess problem and the list of the moves to explain how Alice wins. [10] This process can be read as a synoptic way of unfolding the plot. The list of the moves (as numerous as the chapters of the novel) is written in the language proper to chess players, and it is strictly equivalent to the novel, which is written in a literary language. Both narrate the same drama, in its literal meaning of action: both are two different languages to unfold the same plot. [11] In the liminal chessboard-map, the whole action is already there, virtually contained on the chessboard and precisely detailed in the consecutive list of the moves that follows, and the novel is only a literary translation of what the reader-chessplayer could already have guessed. From the top of the hill, Alice was right: by deciphering in the landscape the structure of a chessboard, she revealed its deep function as a producer of narratives. Alice's adventures are written in the infinite virtualities offered by the game: the chessboard works as a performative creator of narratives.

<21> At the end of this study of Swift and Carroll's texts, we would like to return to the hypothesis we initially formulated. The maps in those texts have a performative function: they do not just illustrate the narratives, but that they actually trigger them. A pragmatic focus on these maps might therefore be fruitful when added to the semiotic perspective. What can this performativity of the map add to our reading and understanding of Gulliver's Travels and Through the Looking-Glass? We believe that it enables us to take the map-as-language seriously, hence finding new tools to rethink the status of cartography within the literary text.

<22> This analysis of Swift and Carroll from a geocritical point of view opens up new different and challeging perspectives in both literary and cartographic studies. The differences that have been highlighted between Gullivers' Travels and Through the Looking-Glass have to deal with the cartographic language more than the literary one. Indeed, those texts which were not published at the same time convey a different relationship to space: Swift possesses a positional conception of space (the map as medium to convey action) whereas Carroll makes use of a relational conception of space, in which space is as much the producer as the product of the action.

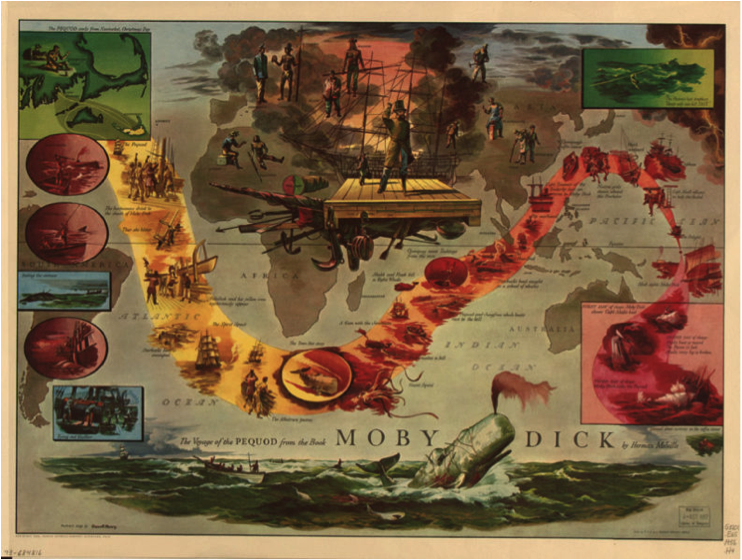

<23> Many authors of literary texts, especially travel narratives, insert maps either to give more realism to the text, or to illustrate the journey, or - as in Swift and Carroll - to trigger the action. Stevenson, Tolkien, [12] Melville (Fig. 6), Defoe - to mention only a few - use embedded maps in some of their narratives. Even if it would be difficult to make a typology of these embedded maps, since we have seen that they are closely related to the narratives in which they are inserted, we can conclude that those maps are rarely purely decorative and that a study on literature cannot avoid a deep reflection on space and how it can be conceptualised.

Notes

[1] Bertrand Westphal, La Géocritique. Réel, fiction, espace (Paris: Minuit, 2007), 197.

[2] «Geopoetics is a transdiciplinary theory and pratice that can be appled to all the fields of life and research, and whose aim is to restore and enrich the relationship between Man and Earth, which has been cut for a long time, with all the weel-known consequences on the ecological, psychological and intellectual levels». (The original quotation reads: «La géopoétique est une théorie-pratique transdisciplinaire applicable à tous les domaines de la vie et de la recherche, qui a pour but de rétablir et d'enrichir le rapport Homme-Terre depuis longtemps rompu, avec les conséquences que l'on sait sur les plans écologique, psychologique et intellectuel.» Kenneth White, La Géopoétique. http://www.kennethwhite.org/, 25/10/13, 16h52.).

[3] Dennis Reinhartz, in The Cartographer and the Literati writes that "although of German origin, [Herman Moll] is Great Britain's most celebrated geographer and mapmaker of the first half of the eighteenth century. The content of Moll's geographies, atlases, maps, charts and globes is diverse and sometimes, spanning the earth and its history as they were known at the beginning of the eighteenth century..." (1). Jeremy Black develops a similar point of view in "Maps and History: Constructing Images of the Past."

[4] In the first editions, this chessboard-map came with a dramatis personae in which all the characters of the novel are referred to as the pawns of a chessboard. The solution to the problem - "White Pawn (Alice) to play, and win in eleven moves" (Carroll, 104) - cannot be taken for granted, and one year before he died, Carroll got rid of this dramatis personae that totally disappeared from the final version, which blurs the link between the chessboard-map and the plot.

[5] The original quotation reads: "Through the Looking-Glass (…) représente le parcours d'Alice sur l'échiquier. Quelle plus belle carte que le damier bicolore d'un échiquier? On note que Carroll prend bien soin de la placer en premier page de son deuxième conte ; repère visuel, clair et pratique, elle doit en effet pouvoir être consultée à tout moment par le lecteur.

[6] Sir John Tenniel (1820-1914) illustrated Carroll's novel from its first publication: his black-and-white drawings contributed to make Alice's adventures famous all over the world.

[7] The original quotation reads: «Ces lieux, parce qu'ils sont absolument autres que tous les emplacements qu'ils reflètent et dont ils parlent, je les appellerai, par opposition aux utopies, les hétérotopies ; et je crois qu'entre les utopies et ces emplacements absolument autres, ces hétérotopies, il y aurait sans doute une sorte d'expérience mixte, mitoyenne, qui serait le miroir. Le miroir, après tout, c'est une utopie, puisque c'est un lieu sans lieu. Dans le miroir, je me vois là où je ne suis pas, dans un espace irréel qui s'ouvre virtuellement derrière la surface, je suis là-bas, là où je ne suis pas, une sorte d'ombre qui me donne à moi-même ma propre visibilité, qui me permet de me regarder là où je suis absent - utopie du miroir. Mais c'est également une hétérotopie, dans la mesure où le miroir existe réellement, et où il a, sur la place que j'occupe, une sorte d'effet en retour ; c'est à partir du miroir que je me découvre absent à la place où je suis puisque je me vois là-bas.» (Foucault, 1984: 47). The English translation comes from: http://foucault.info/ (consulted on March 12th, 2013).

[8] The original quotation reads: «J'ai commencé à m'intéresser aux cartes quand j'ai compris qu'elles n'entretenaient que des rapports très éloignés avec le réel» (Vasset, 2007, 9).

[9] Today as in the eighteenth century, the reader cannot believe in the reality Gulliver describes, but back then anchoring the narrative in "reality" was a convention and a sine qua non condition to be published by avoiding censorship.

[10] The difficulty of this chess problems urged Carroll to delete it in the further editions.

[11] We borrow that idea from Maurice Blanchot according to whom the original work and its translation constitute two languages to tell the very same story (Blanchot, 1959).

[12] See Habermann and Kuhn (2011).

Works Cited

Primary sources

Carroll, L. ([1871] 1992) Through the Looking-Glass, A Norton Critical Edition, New York, London.

Defoe, D. (1719) Robinson Crusoe. W. Taylor, London.

Melville, H. ([1851] 1998) Moby Dick, Oxford university Press, Oxford, New York.

More, T. ([1516], 1992) Utopia. A Norton Critical Edition, New York, London.

Stevenson, R. L. ([1883] 2011) Treasure Island, Oxford University Press, Oxfrod, New York.

Swift, J. ([1726] 1998] Gulliver's Travels, A Norton Critical Edition, New York, London.

Tolkien, J. R. R ([1954] 2007) The Lord of the Rings, Harper Collins Publishers, London.

Secondary sources

Adams, P. G. (1983) Travel literature and the Evolution of the Novel, The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington.

Aït-Touati, F. (2011) Contes de la Lune. Essai sur la fiction et la science modernes, Gallimard, Paris.

Austin, J. (1962) How to Do Things with Words, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Barthes, R. (1982) "L'effet de réel" in Littérature et Réalité, ed. by Genette G. and Todorov, T. pp. 81-90, Seuil, Paris.

Bertin, J. (1967) Sémiologie graphique. Les diagrammes, les réseaux, les cartes, Mouton, Paris.

Besse, J.-M. (2003) Les grandeurs de la Terre. Aspects du savoir géographique à la Renaissance, ENS Editions, Lyon.

Besse, J.-M., Blais, H. et Surun, I. (ed.) (2010) Naissance de la géographie moderne (1760-1860). Lieux, pratiques et formation des savoirs de l'espace, ENS Editions, Lyon.

Black, J. (1997), Maps and History : Constructing Images of the Past, Yale University Press, New Haven, London.

Blanchot, M. (1959) Le livre à venir, Gallimard, Paris.

Bracher, F. (1944) "The Maps in Gulliver's Travels", Huntington Library Quarterly, 8, 59-74.

Brosseau, M. (1996) Des Romans-géographes. essai. L'Harmattan, Paris.

Buell, L. (2001) Writing for an Endangered World. Literature, Culture and Environment in the United States and Beyond. Harvard University Press, Cambridge and London.

Buell, L. (2005) The Future of Environmental Criticism. Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination. Blackwell Publishing.

Calbérac, Y. (2010) Terrains de géographes, géographes de terrain. Communauté et imaginaire disciplinaires au miroir des pratiques de terrain des géographes français du XXe siècle . Doctoral dissertation in geography. Université Lumière Lyon 2. Available on line: http://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr

Caillois, R. (1958) Les jeux et les hommes. Le masque et le vertige, Gallimard, Paris.

Collot, M. (2005) Paysage et poésie ; du romantisme à nos jours. José corti, les Essais, Paris.

Cooper, D. and G. Priestnall (2011) "The processual intertextuality of literary cartographies: critical and digital practices", Cartographic Journal, 48 (4), 250-262.

Deleuze, G. (1969) Logique du sens, Les éditions de Minuit, Paris.

Doiron, N. (1995), L'art de voyager, Le déplacement à l'époque classique, Les Presses de l'Université Laval Klincksieck, Sainte-Foy, Paris.

Foucault, M. (1984) "Des espaces autres (conférence au Cercle d'études architecturales, 14 mars 1967)", Architecture, mouvement, continuité, n°5, 46-49.

Gasquet, L. (2000) "'A perfect and Absolute Blank': carte blanche à Lewis Carroll" in Cartes, paysages, territoires, ed. by Shusterman, R., pp. 97-117, Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux, Pessac.

Gomez-Géraud, M-C. and Philippe A. (ed.) 2001, Roman et récit de voyage, Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne, Paris.

Habermann, I. and N. Kuhn (2011) "Sustainable Fictions - Geographical, Literary and Cultural Intersections in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings", Cartographic Journal, 48 (4), 263-273.

Lando, F. (1996) "Fact and Fiction: Geography and Literature." GeoJournal 38(1), 3-18.

Lévy, J. (2003) "Carte" in Dictionnaire de la géographie et de l'espace des sociétés ed. by Lévy, J. and Lussault M., pp. 128-132, Belin, Paris.

Ljunberg, K. (2012) Creative Dynamics: Diagrammatic Strategies in Narrative. John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia.

Lussault, M. (2007) L'homme spatial, La construction sociale de l'espace humain, Seuil, Paris.

mappingwriting.com (the Literary Encylcopedia)

Madœuf, A. and Cattedra, R. (ed.) (2012) Lire les villes, Panoramas du monde urbain contemporain, Presses Universitaires François Rabelais, Tours.

Magetti, D. (2004) "Voyage" in Dictionnaire du littéraire, Paul Aron, Denis St Jacques, Alain Viala Eds, PUF, Paris.

Mallory, W. E., and Simpson-Housley, P. (eds) (1987) Geography and Literature: A Meeting of the Disciplines, Syracuse University Press, Syracuse.

Mondada, L. (2003) "Performativité" in Dictionnaire de la géographie et de l'espace des sociétés ed. by Lévy, J. and Lussault M., p. 704, Belin, Paris.

Moretti, F. ([1997] 1999). Atlas of the European Novel, 1800-1900. Verso, London, New York.

Moretti, F. (2005) Graphs, Maps, Trees. Verso, London, New York.

Noble, A. G., and Dhussa R. (1990) "Image and Substance: A Review of Literary Geography." Journal of Cultural Geography 10(2), 49-65.

Pasquali, A. (1994) Le Tour des Horizons, Critique et récits de voyages, Klincksieck, Paris.

Peraldo, E. (2010) Daniel Defoe et l'écriture de l'histoire, Honoré Champion, Paris, Genève.

Perec, G. ([1975] 2010) An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, Wakefield Press, Cambridge.

Piatti, B. (2011) A Literary Atlas of Europe - Analysing the Geography of Fiction with an Interactive Mapping and Visualisation System, http://www.literaturatlas.eu/en/

Pocock, D. C. D. (1988) "Geography and Literature" Progress in Human Geography 12(1), 87-102.

Reinhartz, D. (1997) The Cartographer and the Literati. Herman Moll and his Intellectual Circles, The Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, Queenston and Lampeter.

Riffaterre, M. (1982) "L'Illusion référentielle" in Littérature et Réalité, ed. by Genette G. and Todorov, T. pp. 91-118, Seuil, Paris.

Shusterman, R. (ed.) (2000) Cartes, paysages, territoires, Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux, Pessac.

Soja, E. (1989) Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory,Verso Press, London.

Tally, R. T. Jr. (2013) Spatiality, Routledge, The Critical Idiom, London & New York.

Tally, R. T. Jr ed. (2011) Geocritical explorations. Space, Place, and Mapping in Literary and Cultural Studies, Palgrave, Macmillan, New York.

Tissier, J.-L. (1995) "Géographie et littérature" in Bailly, A., Ferras, R. and Pumain, D. (eds) Encyclopédie de la géographie , Economica, Paris, 217-237.

Todorov, T. (1970) Introduction à la littérature fantastique, Seuil, Paris.

Vasset, P. (2007) Un Livre blanc, Fayard, Paris.

Westphal, B. (2007) La géocritique, Réel, fiction, espace. Editions de Minuit, Paris.

White, K (1994). Le Plateau de l'albatros. Introduction à la géopoétique, Editions Grasset et Fasquelle, Paris.

White, K. La Géopoétique, http://www.kennethwhite.org/, 25/10/13,

16h52.

Figures

Fig 1: Gulliver's Travel to Lilliput

Fig. 2: Lewis Carroll's chessboard map

Fig. 3: The chessboard landscape in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass

Fig.4 A map of the World on which is delineated the Voyages of Robinson Crusoe. Supposedly from Woodes Rogers. In the fourth edition of Robinson Crusoe (London: W. Taylor, 1719)

Fig. 5: John Constable, Fen Lane, East Bergholt, ?1817, Oil paint on canvas, support: 692 x 925 mm frame: 911 x 1135 x 105 mm, Tate.

Fig. 6: The Voyage of the Pequod, Herman Melville, Moby Dick (1851)

Return to Top»