Reconstruction Vol. 15, No. 3

Return to Contents»

The Art of Reading Changes; A New Approach to Geographical Landscape / Edwige Motte

Introduction

<1> This paper aims to present one aspect of the possible relations between art and science. It does not encompass the whole epistemic range of this relation but focuses on a precise domain: landscape representations (paintings or old photos) and landscape evolution. This produces and intersection between one science (geography) and one domain of arts (plastic arts). More precisely, it deals with scientific field work and artistic field work: which scientific data useful for a scientific geography may be extracted from a painting or a photo which was drawn / taken in the field and which bears all the weight of the artist's subjectivity?

<2> Interdisciplinary work between art and geography has already taken place many times in Human and Cultural Geography. Many studies have dwelt with the role of artistic representations in the construction of collective landscape imaginaries, territorial identities ... This precise work is different because it makes use of representations as a source of scientific information for Physical Geography in order to increase knowledge about the physical evolution of the coastline. The approach is primarily naturalist.

<3> The coastline encompasses constant changes particularly during the last centuries as it was heavily built. Therefore, the evolution is forced by both biophysical processes (waves, storms, climate change impacting sediment fluxes) and by human impacts. The mobility of the coastline is a key social issue for naturalists. Studying of coastal morphodynamic behaviors allows researchers to grasp socio-environmental changes.

<4> Such an issue implies that past environmental conditions are known. The study of sediment is the most common method to achieve this goal : the age and the structure of sedimentary layers allows for the formulation of an hypothesis about past conditions for deposition (climate, sea level, etc.) and past morphological processes (waves, erosive currents). However, dating techniques such as C14 or optically stimulated luminescence are only effective for sediment older than 200 or 300 years, but not for recent sediments. This is the reason why landscape imagery inherited from past centuries is particularly interesting, including paintings, prints, old postcards bear evidences of coastal landforms, and allows it to reconstruct the possible processes and the associated dynamics. It may play the same role for the last centuries than air photos and satellites images for the last fifty years.

<5> Such a work participates in a new and exploratory scientific field which has been initiated by three very important scientists. Robin McInnes within the frame work of the European project ARCH-MANCH has published various book s (2011; 2013) about British coastal evolution. Nordstrom (2007) has been studying various coastal landscape evolutions around the world. Lastly, Alexis Metzger's book (2012) entitled « plaisirs de glace » proposes to evaluate correlations between climatic phenomena and pictorial productions of the golden age of Dutch painting.

<6> For this specific work, the field site has been chosen so as to express relations between past coastal management and past natural dynamics : it the Rance estuary, a small macro tidal (tidal range may exceed 10 meters) river on the northern coast of France (Channel) which was a very industrious site since the beginning of the 19th the century. (Fig 1) The tidal range was used for tide mills, harbours, navigation against the wind during the flow and all these aspects have progressively built a very original environment which was both considered as a landscape unit and an industrial site.

Fig. 1 The Rance estuary, a small tidal river on the northern coast of France.

<7> Many of the industrial buildings (which were gradually established over the past centuries) are out of use today. However, they have left more or less durable traces on the shores. Since they are considered today as heritage elements their history and decay has been extensively studied (Bazin de Jersey, 1979), Bruneau-chotard, 1982; Leblot, 1993; Brouard; Chaigneau-Normand, 2002).

<8> During the Gaullist years, in the 1960s a huge dam was built across the Rance and used for electricity production through tidal currents. It was considered an important technical achievement and still is. Fifty years later it is the leading French industrial site by the number of visits. This tidal power plant has led local people to reconsider the traces, remnants, ruins of the former industrial coastal sites. Instead of being discarded and outdated objects, they were included in the local identity and environment. Indeed, they show evidences of past water uses and of disappeared micro sedimentary dynamics.

<9> Thus, the construction of the tidal power plant between 1960 and 1966 has significantly contributed to mark a turning point in the identity and environmental history of this territory which has become today both an iconic industrial site and an object of scientific debate. From an identity perspective, the tidal power plant contributed to enhance the traditional "artisano - industrious" past of the 19th century's Rance. From an environmental point of view, the plant, first of its kind in the world, has aroused numerous scientific campaigns. Many scientific approaches (remote sensing, sedimentary survey, etc.) have contributed to report profound modifications of the sedimentary and biological dynamics (Le Guillerme-Maurice, Bonnot-Courtois & all, 2002; Frandbeouf, 2010). " Natural tidal cycles have been replaced by EDF dictated technical's requirements, which have induced a significant reduction of the tidal range and thereby a decrease of high water floodplain and a longer duration of slack waters, accelerating the settling of fine sediments that contribute to siltation on former sand beaches" (Jigorel, 2012).

<10> Diachronic study of landscapes based on a comparison between a set of past iconographic documents, and present photographs and field work will help to highlight the cultural and physical changes and make it possible to study them from both an aesthetic and scientific point of view. The main questions that arise are the following ones:

<11> How did the ancient buildings interfere with natural processes and build an artificialised environment as early as the beginning of the 19th century? What, then, were the main features of the coastal landscape and what was their geomorphologic behavior? Did the tidal power plant change mush of this behavior? Was it as much an ecological turning point as it was considered to be an industrial innovation? How useful may old paintings, engravings, photos be for a scientific research on landscape evolution?

<12> Various recent symposiums, in Great Britain and in France (Geomorphosites, Paris 2009, Art and Geographical Knowledge, London 2009, Art and Geography, Lyon 2013) have explored the scientific relevance of this type of interdisciplinary approach and several papers have already been published suggesting promising opportunities (Nordstrom, 2007; Camuffo, 2010; Portal 2010 et 2011; Regnauld & all, 20113). The ArchManch European project, to which my PhD project belongs, devotes a part of its research package to these new perspectives.

<13> In the first part of this article, I shall present the site and the reasons for which it is studied. Then I shall explain the methods I use to bring together a set of works of art and post cards and to compare them with the present landscape. After that, I shall present my first results and discuss the possible relations between art and science in this precise domain: art as a source for exact environmental studies.

Collecting an iconographic dataset

<14> The first step of this work was to gather an iconographic corpus, as representative and exhaustive as possible encompassing the longest possible period.

<15> In accordance with the research topic (uses, development and changes of the land / sea interface), only representations depicting shores were considered. Images taken at low tide are particularly interesting in that they provide a better overview of foreshore infrastructures and sedimentary context.

<16> Setting together an inventory of existing iconography over a long time involves considering a wide range of landscape vectors. Indeed, as pointed Bouisset & all (2010) in an article referring to the role of images in territorial construction, "Places are invoked over time through iconographic supports evolution: lithographs, postcards, photos, promotional." There are almost no representations of the Rance valley before the end of the 19th century. Only the head towns at the two ends of the estuary (Dinan and Saint Malo) have inspired a significant artistic production from the XVIII century,

<17> In a paper about "images of the Rance," Denise Delouche (1987) offers two main explanations for this fact:

- An administrative division (boundary between two departments: Ille et Vilaine and Côtes d'Armor) unfavourable for the affirmation of the estuary as a fully integrated landscape entity

- A geographical context that restricts the views (restricted land access, rare public space offering views of the valley).

The advent of tourism and recreation and the craze for provincial picturesque have caused a profusion of postcards at the turn of the nineteenth century (Fig.2) that now feed public or private collections. Since my work requires free access to data, recollection photos were limited to public digitized records (Regional Conservatory postcard's website and departmental archives of Côtes d'Armor and Ille et Vilaine).

Fig. 2 Some old postal cards of the shores of the Rance

<18> These photos concern primarily the period from the end of the 19th century until the 1920 s1.[1] (Nb. Accurate dating of the clichés is not easy. When it is mentioned, the name of the publisher can be used to estimate more or less precisely the period of the cliché. Finally, if necessary, the document itself (and not only its reproduction on the web site) may have a stamp and a date on it (though it gives the date at which the post card was sent and not the date of the shooting of the photo).

<19> There are some old maps if their scale is precise enough Only very specific local plans are likely to provide information on morphological elements (notably anthropogenic or sedimentary) the scale of which would be comparable with iconographic documents (Fig. 3). Websites of Regional Heritage Inventory and the National Library of France are privileged sources for this type of data.

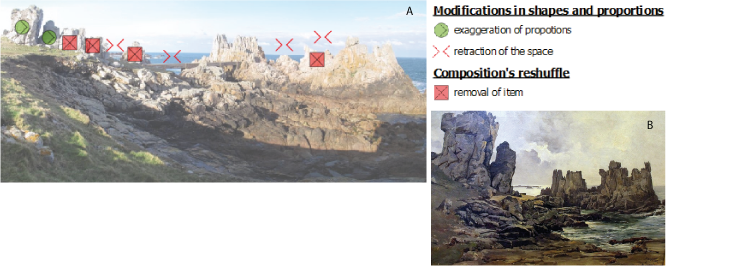

Fig. 3: Local Plans illustrating shoreline portions of the Rance. A: map of the Pontimozon river, localised in the cove of La Richardais and of the harbor of Belle-Grève in the Rance maritime river, 1813. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530169129. B: Castel of Montmarin, map realized by Dubois in 1790 http://patrimoine.region-bretagne.fr

Identification of representative places

<20> To localize the photo, its title or caption may be used but all photos do not have one. The represented landscape may be known enough to guide the observer (distinctive feature, monuments, etc.). Sometimes the place is neither informed nor well known, but a little hint along with a good knowledge of the field or the help of its inhabitants allows for identification. Finally, in some cases, places can resist any possibility of precise localization "even for an expert eye, close-up pictures of the item without great feature, «ordinary" landscapes without the slightest hint may resist precise identification."

<21> In our dataset all the places were finally identified, and therefore can be localized in order to be photographed again today (Fig. 4)

Fig.4: Localization's map of Rance iconography

<22> All these diachronic couples, eventually completed by field surveys have allowed monitoring the main geomorphologic and landscape organization changes during the period.

Photographic restitution of landscapes

<23> Once the location of the landscape was identified, I had to find the exact spot from where the photo was taken or the painting was drawn; i.e., place my camera at the precise place where the eye of the former artist or photograph had been. Most often the alignment of topographic objects structuring the landscape allows a viewer to trace the photographer's line of sight and therefore to locate his or her approximate position. (Fig 5) Different, yet traditional methods are available but they require a lot of preparation (printing of the initial cliché on a layer which is displayed in front of the lens) and they do not work in windy areas (Per Berntsen, 2005). Others methods, assisted by very specific software, require a complex implementation which is not easy to repeat for each shot (Durand & all, 2010). A laser 3D camera, for instance, may be useful for hyper accurate measurements of changes observed between two snapshots of architectural forms with strict geometries, but the method is not efficient for long distance natural forms which have a natural variability such as tidal flats or vegetation. Finally, some new applications developed for Android offer the most satisfactory alternative in terms of both organization and results. The principle is that the application allows the user to adjust the opacity of an image previously downloaded into the device in order to be placed as a layer above the screen. Movement of the observer is then guided by the visual search of the best possible superposition of structural elements of the landscape. Working with a simple Android device has many advantages over all other solutions: ease of movements, effectiveness for the implementation on the ground, etc. Moreover, the resolutions of images are higher with such a device than with many cameras. Other integrated programs can be used (video panorama / location map with GPS, mashups, filters etc.).

Fig. 5 Tracing the photographer's line of sight in order to locate his approximate position.

Scientific field work:

<24> When geomorphologic changes are observed classical "scientific" fieldwork takes place in order to provide informations about the temporal dynamics of observations. In this case sedimentological and micro-fauna analysis of cores and cross-sections may help to estimate the evolution of recent sedimentation rates especially through radio chronologic and radiotopic dating methods (Monna & all, 1996; Pourchet 1994; Alhajji, 2014). Several difficulties may be encountered during fieldwork. First, some places are now impossible to reach due to the privatization of some land or to the erection of new constructions. Sometimes the vegetation has grown high enough to severely limit the visibility (Fig. 6). Last, field trips have to be prepared according to the sea level on past iconographic documents, which involves caring tide cycles and repeat displacements. Moreover, today's tidal range is not exactly the same as it was before the dam of the tide power plant.

Fig.6: Showing the impact of vegetation growing on visibility. The water mill of Montmarin, old postcards from the first 19 's.

Extracting information from diachronic couples of photos: some results as examples

<25> For each pair of documents a standard file with essential informations is planned to be established. It would contain the same type of information as the one of Lausanne University for "geomorphosites"'[2] determination Inventory and evaluation (Reynard, 2006). Some specific coastal parameters are added (type of coast, tides, wave and wind exposure, etc.). For each site, a very precise map can localize the position of the observer (painter, photographer) with his view photo's angle. The file - in case of a web support - can easily contain a panoramic video with precise stop on the shooting point can be added. Landscape evolutions can be enhanced by graphical techniques such as Mash up (merging of two images) or Morphing (Fig.7). Each file will contain the list of changes. Symbols illustrating changes have to be defined in order to create a visual caption. In addition, landscape evolutions can be enhanced through graphical techniques such as Mash up (merging of two images) or Morphing. (Fig.8) Finally, for sites which have generated field surveys, graphics or observational drawing complete the form.

Fig. 7: Illustrating mains changes by visual captions. The beach of Saint Suliac A: Painting by Antoine Guillemet, 1883, private collection; The same landscape today, Photo, Edwige Motte, 2013

<26> Since Antoine Guillemet has painted the beach of Saint Suliac, the little harbour has known various changes. The painting shows the place as it was when the quay did not exist. We can clearly observe that the sea reaches houses. Today, a road and a pathway separate the village from the beach. We can also notice the growing of vegetation on the slope due to entropic afforestation in the right corner of the picture. Finally, field work allowed the discovery of the actual estate of the wind mill we can see on the upland.

Fig. 8: Enhancing landscape changes by Mashups. Le moulin du Montmarin.

<27> Conclusion: art and science (1): Art as tool for science making. The following discussion focuses on non-photographic artistic Medias (drawings, paintings, engravings). Although postcards may contain some tricks (Staszak 2013), generally, their realism is not equivocal. It is different with other media which, even if they are few on the territory of the Rance, are abundant on other portions of coastline. Deformations related to the subjectivity of the artist should be considered to avoid dangers of a too literal interpretation.

<28> A first specific method for assessing the evolution of coastlines out of paintings was developed in England by McInnes and his team (McInnes et al, 2011). They adopt several criteria for identifying how true to landscape a document is or is not, and they have elaborate a specific ranking system. Their main criteria are artistic style, type of subjects, nature of the medium, production period. In England, the Pre-Raphaelite painters were very keen to be as "faithful" to nature as possible. At the same moment in France and in Brittany, for example, there is no specific artistic movement as reliable as British ones. (Fig. 9) Painters such as Eugène Isabey or Alexandre Nozal had different ideas. So the English ranking system cannot be used as such in France.

Fig. 9: Comparing Pre Raphaelites realism with Britain impressionism. A : 'Hoy from the Black Craig Orkney », Edward Hargitt, Watercolor, 1875; B : Fortifications of Saint Malo, Eugène Isabey, oil on paper, around 1850

<29> A critical appraisal of my set of artistic representations of Brittany shores has allowed me to confirm the general geographic accuracy in representation. Nevertheless, artists do take many liberties. Among the special effects which are observed, the most frequent are modifications in shapes and proportions (contours that are exaggerated, or the aestheticization of contours, changes in scales). (figure 10) Composition reshuffle is also observed, but to a lesser extent (Motte, 2014). Very often a painter will depict some element with a very high level of precision and, on the same painting, will slightly move another element so that the composition of the whole image fits better with the requirements of the historical period.

Fig. 10: Assessing realism comparing today landscape with past 19th painting. A: Actual Landscape, photo, Edwige Motte, 2013; B: Rocks near the lighthouse in Ushant, Emmanuel Lansyer, oil on canvas, 1884.

<30> Engravings, lithographs, and prints are more objective because they are aimed at documenting a political purpose: to show, under the second Empire (napoleon III) and the beginning of the third republique (1870 - 1914), the unity and the beauty of the French territory. They materialize a plastic approach where "before focusing on aesthetic significance, landscape was considered through politic and topographical meanings, it was province, country or region" (Besse, 2000). (The word "chorography" which echoes to an attention to detail, to an inventory, seems almost appropriated to describe a pictorial approach finally similar to a geographical monograph).

Conclusion: Art and science (2): science making as a tool for art history.

<31> Obviously what the painters saw is not what we see today, as the landscape has changed. This means that any concept of "imitating" nature has to be replaced within the context of what nature was at the moment. Today's nature is not what nature was one hundred years ago, especially in coastal areas. When Courbet paints a breaking wave instead of an immobile cliff he knows that sea scape is an optical illusion and that no painting may express the movement which is the base of the landscape. Landscape painting must not be only understood as a representation of landscape but as an interpretation of what is mobile, changing or stable in a specific location.

<32> In the words of Mérot (2009) landscape painting goes "beyond the simple observation of landscape and remains the genre "par excellence" of personal expression where reference to what is agreed to call the real world is not essential." This distinction is essential, and the resulting conclusions are very general. Whatever the type of work concerned, any representation is potentially subject to a process of reinterpretation of the mobility of reality. Conscious or not, perceptual filters are inherent to every regard as supposedly objective they are. As an example, the illustration by Felix Benoist of the rocks of the Ushant's island (figure 11) is interesting. Political and documentary vocation is claimed (the work is part of a long series of illustrations commissioned by the state to provide "official" image of the territory of contemporary France); however, excess in proportions and aestheticization of forms is undeniable. It is probably the inconsistent expression of fantasies related to dangers associated to a distant and mysterious island...

<33> As I already said, here are very few paintings concerning the Rance River and many postcards. Several studies have already highlighted the uneven plastic interest of natural spaces, particularly emphasizing a great disdain for wetlands in the French society since the eighteenth century (Goeldner-Gianella, 2011). The Rance is an industrial/agricultural estuary. This has some implications on the type of work of art which describes it (few paintings, many post cards). The relation I explore between my iconographic data and the scientific information may then be site specific. Along another coast line, such as the cliffs of Normandy, which were preserved from industry, I would have had another set of graphics and probably another set of scientific data extracted from. So the relation between art (graphic) and science (geomorphic evolution) is highly site dependant and must be considered as a very complex issue. Would I find the same relation in a totally natural site (supposing that such place would really exist)?

Notes

[1] From 1900 to 1914, the postcard experienced significant growth (there is even talk in this respect "The Golden Age of Postcards"). Many publishers encouraged photography in all the towns of France with numerous photographs of the monuments or general views, leaving us a legacy of great testimony to a still predominantly rural France. Between 1910 and 1914, the French production spent from 100 million to 800 million cards published. The decline of the postcard began after the First World War, when challenged by the phone. http://archives.cotesdarmor.fr/index.php?page=cartespostales

[2] « A géomorphosite is a landform with particular and significant geomorphological attributions, which qualify it as a component of a territory's cultural heritage (in a broad sense) », Panizza & Piacente (2001)

Works Cited

Agarwala, Aseem, Soonmin Bae, et Fredo Durand. « Computational Re-Photography », 7 avril 2010. http://dspace.mit.edu/.

Alhajji, Eskander, Iyas M. Ismail, Mohammad S. Al-Masri, Nouman Salman, Mohammad A. AlHaleem, et Ahmad W. Doubal. « Sedimentation Rates in the Lake Qattinah Using 210Pb and 137Cs as Geochronometer ». Geochronometria 41, no 1 (1 mars 2014): 81-86. doi:10.2478/s13386-013-0142-5.

Berntsen, Per. « Changes - a rephotographic project ». Forandringer, The Norwegian Industrial Workers' Museum, 2009.

Besse, Jean-Marc. Le goût du monde, exercices de paysages. Acte Sud. Paysage. ENSP, 2009. Mérot, A. Du paysage en peinture dans l'occident moderne. Gallimard. Bibliothèque des histoires, 2009.

Bonnot-Courtois, Chantal, Bruno Caline, Alain L'Homer, et Monique Le Vot. La Baie du Mont-SaintMichel et l'Estuaire de la Rance. Pau: CNRS, EPHE, Totalfina ELF, 2002.

Bouisset, Christine, Isabelle Degrémont, et Jean Yves Puyo. « Patrimoine et construction de territoires par l'image : l'exemple du pays d'Albret (France) et de ses paysages (XIXe- XXIe siècles) ». Estudios

Geográficos 71, no 269 (30 décembre 2010): 449-473. doi:10.3989/estgeogr.201015.

Bruneau-Chotard. « Les moulins à marée de la Rance », Annales de la Société d'Histoire et d'Archéologie de l'Arrondissement de Saint-Malo, 1982.

Bazin De Jessey. « Les traversées de la Rance au cours des siècles ». Annales de la Société d'Histoire et d'Archéologie de l'Arrondissement de Saint-Malo, 1979.

Brouard, H. « Les Bateliers de La Rance ». Annales de la Société d'Histoire et d'Archéologie de l'Arrondissement de Saint-Malo, s. d.

Camuffo, Dario. « Le niveau de la mer à Venise d'après l'œuvre picturale de Véronèse, Canaletto et Bellotto ». Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine n° 57-3, no 3 (24 septembre 2010): 92-110.

Chaigneau-Normand, Maogan. La Rance industrieuse, espace et archéologie d'un fleuve côtier. PUR. Art et société, 2002.

Delouche, Denise. « Images de la Rance ». In La Rance millénaire, 145. Bannalec, 1987.

Frandeboeuf, Fanny. Evolution Géomorphologique et sédimentaire de l'Estuaire de la Rance depuis 1952. Mémoire de Recherche. Université Rennes 2, 2010.

Goeldner-Gianella, Lydie, Corinne Feiss-Jehel, et Geneviève Decroix. « Les oubliées du "désir du rivage" ? L'image des zones humides littorales dans la peinture et la société françaises depuis le XVIIIe siècle ». Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography, 20 mai 2011. doi:10.4000/cybergeo.23637.

Jigorel, Alain, Jean Luc Métayer, et Jean Yves Brossault. Synthèse du suivi de la sédimentation dans les vasières de la Rance. Rennes: Laboratoire GCGM-Géologie & Environnement; INSA, 2012.

Le Bot. « La Rance et ses bateaux aux derniers jours de la voile ». Annales de la Société d'Histoire et d'Archéologie de l'Arrondissement de Saint-Malo, 1993.

Le Guillerm-Morice. « Les conséquences régionales du barrage de la Rance ». Annales de la Société d'Histoire et d'Archéologie de l'Arrondissement de Saint-Malo, s. d.

Mc Innes, Robin. A coastal historical resources guide for England. The crown Estate. (Marine estate research projet), 2011.

Mc Innes, Robin. Art as tool in support of the understanding of coastal change in Scotland. The crown Estate. (Marine estate research projet), 2013.

Metzger Alexis. Plaisir de Glace, essai sur la peinture hollandaise hivernale du siècle d'or. Herman, 2012. 115p Monna, F., J. Lancelot, M. Bernat, et H. Mercadier. « Taux de sédimentation dans l'étang de Thau à partir des données géochronologiques, géochimiques et des repères stratigraphiques ». Oceanolica Acta 20, no 4 (1 janvier 1997): 627-638.

Motte, Edwige. « L'usage de représentations artistiques de rivages comme outil de connaissance de l'évolution du littoral : exemple bretons », Revue d'Histoire maritime, 18 (2014).

Nordstrom, Karl F., et Nancy L. Jackson. « Using Paintings for Problem-Solving and Teaching Physical Geography: Examples from a Course in Coastal Management ». Journal of Geography 100, no 5 (septembre 2001): 141-151. doi:10.1080/00221340108978441.

Portal, Claire. « Reliefs et patrimoine géomorphologique. Applications aux parcs naturels de la façade atlantique européenne. » Thèse de doctorat, Université de Nantes, 2010. http://tel.archivesouvertes.fr/.

Panizza, Mario. « Geomorphosites: Concepts, Methods and Examples of Geomorphological Survey ». Chinese Science Bulletin 46, no 1 (1 janvier 2001): 4-5. doi:10.1007/BF03187227.

Pinglot, J. F., et M. Pourchet. « Radioactivity measurements applied to glaciers and lake sediments ». Science of The Total Environment, Environmental Radiochemical Analysis, 173-74 (1 décembre 1995): 211-223. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(95)04779-4.

Portal, Claire. « Du socle au paysage : essai pour un nouveau regard sur les reliefs ». Projet de paysage, noURL: http://www.projetsdepaysage.fr (12 juillet 213apr. J.-C.).

Regnauld, Hervé, Heulot Patricia; Motte Edwige 2013. « Art and Science are alike ». Acte du colloque Art et Géographie - Esthétiques et pratiques des savoirs spatiaux - 11,12,13 fevrier 2013, Lyon.

Reynard, Emmanuel. Fiche d'inventaire des géomorphosites. Université de Lausanne: institut de géographie, 2006. http://www.unil.ch.

Staszak, Jean-François, Lionel Gauthier, et Nicolas Crispini. « Epreuves exotiques ». Dorade, no 5 (2013): 236-38.

Return to Top»