Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 1

Return to Contents»

Gesture, Intimacy, and Violence in Contemporary Artists' Books / Lauren Benke

"An age that has lost its gestures is, for this reason, obsessed by them. For human beings who have lost every sense of naturalness, each single gesture becomes a destiny. And the more gestures lose their ease under the action of invisible powers, the more life becomes indecipherable." - Giorgio Agamben, "Notes on Gesture" [1]

<1> The problem of the archive is a problem of lost gestures. The idea of the ephemeral body has shaped the development of performance and archival studies since the 1960s, when Richard Schechner described the theater as a transient medium that has "no original artwork at all" [2] and Marcia B. Siegel wrote that dance "exists at a perpetual vanishing point [. . .] it is an event that disappears in the very act of materializing" [3]. Even as archivists constantly innovate methods for preserving the gestures of performance art and embodied experience, the shift toward digitization means that, as well as the gestures of the dancer or actor, the very process of accessing the archive loses something of its tactile, gestural quality. Now, gloved hands carefully turn manuscript pages far less often than arrow-key-clicks move digitized pages across screens. Although gesture is not removed entirely from the process of reading or archival research, the movements have become smaller and less tactile, reduced by the screen's separating presence, and the intimacy and embodiment with which we interact with texts is mitigated. Gesture, broadly defined here as any real or imagined representation of the moving body, provides a unique point of access for renewing the intimacy between reader and text. It facilitates unique incarnations of intersubjective experience, embodied memory, and performative interactions with artworks. Detailed attention to movement provides a point of critical focus not only for considering ephemerality in performance arts and archives, but also for reclaiming the gestural intimacy with which we relate to diverse pieces of art as readers and critics. This focus on expressive body movement extends out of and around art works—we might consider gesture as represented in literary, performance, and visual art forms, but equally or perhaps more important are the gestures of creating that preceded the work, ways that gesture operates as a theoretical axiom underlying a piece of art, and the gestures required for accessing, reading, or archiving a finished work. Gestures are expressive body movements that tangibly represent the body's way of being in space, in the world, and in relation to other beings. They are involved in every aspect of human intimacy—from interactions between infant and caretaker, to sexual rhythms, to gestures of the deathbed—as well as being integral to ceremonial rites and rituals across cultures. Yet, as well as existing in the present moment, gestures are cross-temporal sites of bodily memory—as in Richard Schechner's canonical performance studies postulation that performance is "twice-behaved" behavior—and thus construct within the moving body an archive of past events and a space for somatic reenactment [4].

<2> Though possibilities for gesture study might be productively applied to diverse literary and artistic works, the structural form and aesthetic character of contemporary artists' books—time-based, material artworks that join performance art and gesture with text and object—makes them an especially apt medium for this discussion's focus. Contemporary works by several book artists—Alicia Bailey, Christine Kermaire, Elsi Vassdal Ellis, Bonnie Thompson Norman, and Maureen Cummins—will be evaluated as a case study for the ways in which gesture and intimacy interact in an innately gestural, and thus performative, art form [5]. The diverse structural forms of artists' books necessitate physical engagement with the work in such a way that accessing the art object is itself a performance. As in the gestures of dance or theater, the gestures of interacting with artists' books are subjective, dependent on a transitory and individually experienced series of movements. Access to and tactile interaction with the archival material of the artists' book requires a performative gesture which, like all performance arts, eludes precise preservation in an archive. Further, the convergence of gesture and intimacy in contemporary artists' books allows for uniquely embodied experiences of their content. The forms of artists' books inhere a sense of fragility—the reader is constantly aware of the fact that the piece functions as a singular kind of meeting between the tactile intimacy of interacting with a book, a form we are used to being allowed to touch, and the fragility and inaccessibility that characterizes other forms of art. Artists' books allow the reader an uncommon permission to touch art, and with it the potential for destructive gesture—awareness that a wrong move on the part of the reader could unravel, tear, or otherwise damage an art object. Artists' books concerned with violence, therefore, represent a powerful intersection between represented gestures of violence, imagined or otherwise, and the reader's intimate understanding of her own potential destructive gesture. Artists' books function as sites of remembered gesture, retaining the movements of previous performance and an aura of bodily memory. The works discussed here exhibit a distinctive self-awareness of ways that forms and gestures of artists' books reinscribe gestures on the body of the book, artist, reader, and perpetrator or recipient of violence. Attention to these contemporary artists' books in connection with interdisciplinary approaches to gesture studies reveals that gesture exists at a powerful point of intersection between intimacy and violence and, more broadly, allows for a reclaiming of an embodied, moving, mutable relationship to art and the archive.

<3> Artists' books developed as a distinctive art form over the course of the twentieth century, though antecedents to the genre can be traced back to the earliest history of printing. The artists' book as we know it has a clear inheritance from artists including William Blake, Gelett Burgess, and Stéphane Mallarmé, among others, and is imbricated with nearly every art movement of the twentieth century: experimental typography, Futurism, Surrealism, Expressionism, Dada, Lettrism, Fluxus, and Conceptualism [6]. The concept of the book as an artistic production, though, is too broad a category for what we currently think of as the artists' book; an effective definition requires the additional stipulation that the work must self-consciously negotiate its form as a book as part of its artistic intention. Contemporary artists' books are designed as original artwork rather than reproduction, and experiment with diverse structural book forms that implement a mutually informing interplay between book form and artistic intention [7]. The self-aware implication in the very definition of artists' books might be extended toward the gestural and performative possibilities for the text objects. The artwork both employs and subverts expected structural book forms—the traditional formula for page turning is altered or completely absent—and requires its reader to enact a particular series of gestures which build toward a larger performance of reading. This process constitutes a renegotiation of the book form into an art object that defines itself through structural and somatic reinterpretation. Interactions with the unique structural forms of artists' books allow artists and readers access to an extensive phenomenology of gestures and the implications, both performative and intimate, those entail.

<4> The study of gesture might be said to originate in the elocutionary guides of antiquity—Aristotle and Quintilian, among others, detailed the use of particular gestures for rhetorical emphasis. In the rhetorical tradition, gesture most commonly succeeds thought and is used as an accent to language, but even as early as Institutio Oratoria, Quintilian considers gesture as potentially agentive outside of language: "[gesture] can often convey meaning even without the help of words" [8]. The first treatises devoted entirely to gesture appeared in the early seventeenth century: Giovanni Bonifacio's L'Arte de' Cenni in 1616 and John Bulwer's Chirologia: or the Naturall Language of the Hand, the first of its kind in English and published in 1644 [9]. Gesture began to garner interest in relation to philosophy and the origins of human life in the eighteenth century, particularly in France. It also formed the basis for universal language schemes in which a codified system of hand movements could replace language. Today, the academic study of gesture is an intensely interdisciplinary endeavor, focused largely on anthropological, communicative, and psychological implications of body language. Studies of gesture are most often concerned with either non-representational gestures, those in an anthropological or communicative mien rather than as portrayed in art, or gestures that are an element, but not often a particularly stand-alone element, of larger performances. Yet, as dance movements or stage directions construct ballets and plays, each individual gesture functions as a unit of a larger, if less clearly defined, expression of performativity. Gesture is a unit of performance; performance is a concatenation of gesture. This question of performance troubles the boundaries between public performance and intimate human or artistic interactions. Gesture is vital to both of these categories, though, and serves as a significant unit in the construction of each. As such, the discussion of the following artists' books will attempt to delimit the functions of gesturality in both the connections and oppositions between intimacy and performativity.

<5> Gesture connects provocatively to both psychological and phenomenological implications of intimacy and artistic production. In an interview for a web series titled "Beyond the Gallery," book artist Alicia Bailey comments on the experience of working with objects, the time-based nature of artists' books, and the reader's intimate experience with the art form: "What I hope that people take away from an experience with my work is a broadening of their world to include things like spending an extended period of time with an artwork [. . .] what it feels like to have an intimate experience with an art object, but to be able to hold that in your hands and then not know what's going to happen when you turn the page" [10]. Bailey suggests that the time-based, object-centered genre of the artists' book is unique primarily because of the individual, intersubjective, and intimate experiences readers can have with a work of art. Diverse incarnations of gesture theory are similarly focused on the communicative, intimate potential of gesture, either as an innate human characteristic or a phenomenology. Vilém Flusser establishes a detailed phenomenology of gestures—defined in the most basic form as movements of the body that express being and are the concrete representations of our being-in-the-world [11]. Flusser attends to diverse gestures—writing, making, loving, destroying, and smoking a pipe, among others—as expressions of consciousness and the complex, relational connection between the gesturer and the world. Flusser's sustained phenomenological discussion of gesture evinces the broad array and fundamentality of gesture to ways of being-in-the-world that underlie all intimate interactions. From the developmental psychology perspective, gesture, in connection with rhythm, is the fundamental method of developing intimacy and mutuality between mother and infant, and with others later in life. Ellen Dissanayake describes infant rhythmic gesture as an "unverbalizable [...] sense of intermingled movement and sensory overlapping that characterizes infant experiences, as it also characterizes subsequent experiences of love and art" [12]. Dissanayake's argument moves from infant communication through anthropological discussions of the nexus of gesture, intimacy, and art in many aspects of human life: belonging—seeking, tool-making, and ceremonial rituals [13]. Gesture is thus both a phenomenological building block of the consciousness's means of being-in-the-world and a unit that helps to construct human rituals of intimacy and ceremony. Both of these functions of gesture are enmeshed with the question of performativity, and exist on a spectrum that ranges from a fundamental physical expression of being-in-the-world to the performance of elaborate ceremonial rituals. Intimacy and performance meet at the point of gesture.

<6> Though we might consider gesture as any expressive movement of a body, human or nonhuman, both the study of gesture as a whole and the gestures of relating to artists' books in particular are primarily focused on the hand. The gestural study of antiquity is largely concerned with specific hand gestures and their role in adding emphasis to elocution. This suggests a sense of simultaneity and reciprocity between gesture and speech as well as gesture and thought: movement informs language and language informs movement. Dissanayake argues that the hand gesture is vital to both intimacy and the production of art. Hand gestures are the most rhythmic and fully developed of the infant's gestures, and move throughout development toward making and using tools and creating art by hand [14]. The hand gestures of making and interacting with artists' books are then descendents of an inborn human predisposition. Though any representation of the moving body may be read as significant, the fact that those concerning artists' books are almost entirely situated in the hand opens up numerous possibilities for the sense of what it means to make art or engage intimately with a person or an art work on a fundamental level. Flusser also attends to the particular significance of the hand gesture:

"The words we use to describe this movement of our hands—take, grasp, get, hold, handle, bring forth, produce—have become abstract concepts, and we often forget that the meaning of these concepts was abstracted from the concrete movements of our hands. That lets us see to what extent our thinking is shaped by our hands, by way of the gesture of making, and by the pressure the two hands exert on objects to meet." [15]

<7> Flusser makes a particularly significant point here regarding the shaping of thought through the hand gesture of making. The existence of a synchronized, dialectical relationship between gesture—particularly the hand gesture of making—and thought would suggest that the gestural processes both of making an artists' book and receiving it constantly inform thought [16]. It is not, or not primarily, the content of the artists' book that produces the thinking experience of reading it, but rather its gestural functions.

<8> We might consider all artists' books performative to the extent that they are aware of their form and that—from artist's intention, through the book's position in the archive, to the reading gestures of individual viewers—the form produces and is produced by an embodied act for an individually experienced effect. It is necessary, however, to draw out the difference between this sense of innate performativity and the tradition of artists' books that are self consciously performative. Particularly in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the conceptual art works of the Fluxus group began to make new connections between performance arts and printed materials; two of the most notable of these are George Brecht's Water Yam (1963) and Yoko Ono's Grapefruit (1964) [17]. Both of these works contain imperatives to readers (performers) to perform actions dictated by the book. Ono's instructions in particular obfuscate questions of performer and the expected performed action; "A Piece for Orchestra" reads:

"Count all the stars of that night

by heart.

The piece ends when all the orchestra

members finish counting the stars, or

when it dawns.

This can be done with windows instead

of stars." [18]

<9> Within the form of an artists' book, Ono's text functions as a poetics of stage direction in which identified musicians are told to perform an action that, while specific, is not specific to their usual, musical medium. The instruction is in flux, seeming to erase itself as it concludes by suggesting that windows can be substituted for stars. We might draw a line, though, between books like these that are performative in form and content and books that have a performative element to their form—either self-consciously or as a collateral effect of structure.

<10> Contemporary artists' books contribute uniquely to performance study's polemical concern with the ephemeral and the "live." Performance and archival studies in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have been troubled by the persistent notion of the disappearance of the "live" and the irreproducibility of dance and theater art. Peggy Phelan, for instance, argues that performance "becomes itself through disappearance" and that the performing body is neither a record nor a means of recording performance [19]. Rebecca Schneider's work on "performance remains" convincingly argues for a broadening of this preoccupation, suggesting that rituals of archival access and performance as bodily memory can constitute presence and repetition, rather than only disappearance [20]. She suggests that the performing body is:

"not only disappearing but resiliently eruptive, remaining through performance like so many ghosts at the door marked 'disappeared'. In this sense performance becomes itself through messy and eruptive reappearance, challenging, via the performative trace, any neat antinomy between appearance and disappearance, or presence and absence—the ritual repetitions that mark performance as simultaneously indiscreet, nonoriginal, relentlessly citational, and remaining." [21]

<11> Schneider's work also pushes back against the inflexible dichotomy between material document and "live" performance. Artists' books fit compellingly into such postulations as they are both the material documents of the archive and sites of performed gesture that rely on repeated gesture and bodily memory to resist disappearance in the archive. The following artists' books, by functioning at an intersection of gesture, intimacy, and violence, trouble the persistent distinction in performance studies between live art and material object.

<12> Alicia Bailey's Mercy (2004) provides a distinctive example of a dialectical relationship between gesture and thought and the gesture of hands shaping the reading process [22]. The body of the book is a rosewood box, which contains a scroll of paper attached to the interior of the lid. The scroll, a translucent patterned paper, is wrapped in a long string; the string is much longer than functionally necessary to keep the scroll in place, and so its unwrapping or rewrapping become extended processual gestures. The reader must engage intimately with the art object for a defined period of time, which is consistent with Bailey's stated goal of giving her readers a time-based experience and an extended, intimate encounter with an artwork.

Figure 1. Alicia Bailey, Mercy. 2004.

<13> Manipulating the vertical position of the scroll without unrolling it fully reveals a small conch shell at its center, which exists chiasmatically between the making and reading hand gestures—the artist's gesture of attaching the scroll to the shell and wrapping it around meets the reader's unwrapping process to reveal the shell in both a literal and figurative ring structure. The piece draws attention to questions of permanence and fragility—the box as opposed to the scroll—and though text is present, it fades into the texture of the scroll, and the reader's anxiety about unrolling the paper too far almost certainly prevents a reading of the whole poem. Fittingly, the poem, Jane Kenyon's "Notes from the Other Side," erases itself in content as well as in its place in this artists' book: "now there is no more catching / one's own eye in the mirror" [23]. The form of this piece, and the attendant gestures required to access it, create an intimate experience of intersubjectivity between the reader and both the artist and the book itself. The hand gestures of making and receiving inform thought to the extent that the book's existence is or gestures, rather than informs, the experience of its content. As in a temporal art form like dance or theater, Mercy is as much about what is absent as what is present—the offstage body of the actor in a drama is here an offstage piece of text or material point of access. Engagement with the book is a performance, and its ontology is thus partially situated in ephemerality; but both the bodily memory of gesture and the continued presence of the material constitute a remain: a presence as well as an absence.

<14> Without ostensibly violent content, the possibility of a destructive action persists due to the fragility and uncommon tactile access to artworks on which the genre of artists' books is predicated. Bailey also draws out this subtle connection between the tenuous and embodied gesture of reading and the disembodiment of shed parts, at times parted with violently. Shedding (2010) progresses through a 21-day catalogue of specimens "shed" by the artist, scanned and printed at a 500% scale [24]. The work moves though a litany of bodily residue that seems to become gradually more intimate—progressing through chin hair, blood from a home cholesterol test, fingernails, ear wax, eye crust, to blood for an STD test. Each page features text in the form of the artist's commentary on that day's shed fragment, several of which attend to a sense of gesture or violence.

Figure 2. Alicia Bailey, Shedding. 2010.

<15> The page with a shed eyelash reads: "it seems a gesture of great tenderness to lift an eyelash off the cheek of another. As I lift the eyelash off my own cheek I feel a surge of tenderness towards myself." As the text progresses, the artist begins to hope to be wounded in order to shed: the text "when I started this project I was hoping I'd have a flesh wound, an abrasion" precedes later pages featuring remains from a hangnail, spider bite, shin scrape, and paper cut. Like the shell in Mercy, these fragments exist at a cross-temporal meeting point between the violent gesture that led to the artist's shedding and the reader's awareness of the fragility of the book, and by extension the fragility of his own body. The form and temporal intimacy of the artists' book allows for a disturbingly intersubjective experience and melding of the artist's and the reader's bodies. This specific performance of gesture—for an audience of a single artists' book reader rather than an auditorium of spectators—is able to create a unique level of intimacy between artist and reader at the point of the book.

<16> Physical violence is composed, at a basic level, of gesture. The action resonates through both bodies, the party inflicting a wound and the one receiving it, and the empathic experience of art allows the event to vibrate in the reader or spectator's body as well. The violent action is a gestural remainder, remembered in the body of the performer or book that memorializes it. The gestures required to memorialize the dead or cope with the effects of violence are also remembered by living bodies—the movements of burial, funeral, and mourning [25]. The formal qualities of artists' books allow them to perform a particularly effective embodied memorialization of violence, a fact that the community of book artists has often proved. On March 5th, 2007, a car bomb exploded on al-Mutanabbi Street, the street of the booksellers, in Baghdad, Iraq, killing 30 and injuring more than 100. In 2010, the Al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition issued a call to book artists to produce work honoring what was lost that day, and representing "the ultimate futility of those who try to erase thought" [26]. The artists' books produced in response to the project are an extremely poignant memorial to the lives, as well as the intellectual history, lost on al-Mutanabbi street. The fact that the bombing occurred on a street of books makes the memorialization of the event through the book medium still more effective, as the project attends to broken bodies of both humans and books. This is a precise example of the self-aware status of the book form as integral to the artistic intention of the artists' book.

<17> Christine Kermaire's Resilience of Al-Mutanabbi Street (2011) is composed of fragments of Arabic quotes from Kant's Critique of Pure Reason [27]. The accordion book form—a series of layered and folded textual bodies—is littered with fragmented quotes and frayed strings projecting from the hinge points of the pages. The form connotes fragility in the sense that nothing is completely bound together and could be thrown open at any moment, which effects an imagined embodiment of the gesture of bombed fragments of text exploding and slowly floating back to earth. The memorialization of broken books, of course, extends implicitly to the memorialization of broken bodies, and the red fragments become the image of blood, flesh, and colored book fragments existing simultaneously. The piece is more than a disturbingly visceral memorial to broken books and bodies, however; the work resonates because engaging with it in a tactile, gestural way produces an intersubjective experience not with the artist but with the books and bodies that received the violence of the bombing. The gestures constructed in the body of the book are a cross-temporal bodily memory of past gestures. To return to Dissanayake's formulation of gesture as primary means of forming mutuality with others, the gesture of interacting with violent content in book form offers an immediate intimacy with wounded bodies that another medium would be unlikely to achieve as quickly or completely. Kermaire's second contribution to the project, Memory of Al-Mutanabbi Street (2012) shifts focus to a still more person-centered memorial—in varied accordion format, Kermaire represents the names of the people killed in the bombing alongside the image of an endless screw entwined with a red thread [28]. Like the red fragments in Resilience, the thread suggests an endless stream of blood, paralleled by the image of the screw turning ever lower into the earth. The book is composed of four leaves—accordion folds in opposite and layered directions. The effect of layered folds moving toward the center and the close proximity of the names imply a community among the victims of violence. The gesture of reading creates a sense of burrowing to the center, but both the physical difficulty in the reading—the folds must be peeled back at just the right angle and in the right order to avoid becoming stuck—and the content elicit a feeling of reluctance and discomfort in the reader. The form enacts the gesture of a burial, as names of the dead are inscribed deeper and deeper into the imagined ground of the book. Rather than the explosive gesture produced by the fragments of paper in Resilience, Memory drives continually downward. In engaging the reader gesturally in this sense of burial, the piece facilitates a sense of complicity and engagement with the body of the text and the imagined bodies of the victims.

<18> Elsi Vassdal Ellis's first contribution to the project, Al Mutanabbi Street I (2011) performs a distinctive representation of the book's embodiment [29]. The verso pages feature names, occupations, and ages alongside various quotes about books and reflections on issues related to al-Mutanabbi Street. The recto pages are photographs of injured books: layered representations of the subtle violence—folds, stains, water damage—inscribed on the bodies of books. The text reflects the awareness of the book as a body that can be injured, and the final lines of text focus on the tangible, spatial world of reading: "What I do know is that I can escape this world and get lost in the alleyways between characters on the page [. . .] all I have to do is pick it up, open the cover and allow my eyes to feast upon the letters forming words forming sentences forming paragraphs forming chapters." The conclusion's focus on escapist gestures of reading emphasizes the convergence between the current reading gesture and the collective memory of previous, present, and future gestures of moving through books. Similarly, Bonnie Thompson Norman's Remember: people of Al-Mutanabbi Street (2011) develops a visceral, gestural memory of violence, and, again, the gestures embody the performative remains of both a violent action and the gestures used to memorialize it [30]. The textual content is, on the verso pages, an Arabic translation of "The memory of these people is in our hearts" and "Rest in Peace." The rectos display a litany of names, ages, and occupations of the dead and injured. Each page features a subtle, almost delicate, burn mark, which reveals the text on the next page and draws the reader downward into the text and the repeating series of names. As this processual gesture continues, repeated names or pieces of text seem to clamor for attention: the phrase "lost one of his arms," for example, gradually shifts the ocular gesture of reading to one of surveying wounded bodies. Thompson Norman inscribes the text with a gestural memory, through which the reading body finds a unique cross-temporal intimacy with the body that has been victim to the violent act. The intersubjective gesture of chiastic convergence between reader and artist at the site of the text, which implicitly questions violence toward the book, is deeply complicated and intensified by the inclusion of fatal violent gesture in the work's content.

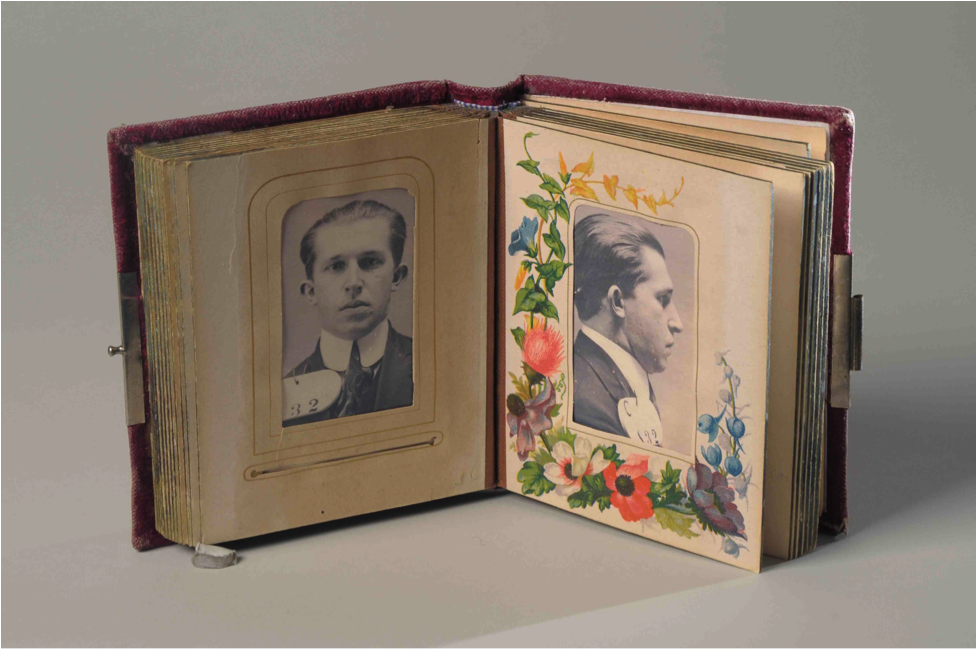

<19> As well as the proliferation of responses to the Al-Mutanabbi Street Project, works that memorialize diverse violent acts, explicit or implicit, facilitate a uniquely gestural and intimate experience of interacting with an artwork. Interestingly, a survey of Maureen Cummins's artists' books reads similarly to Flusser's Gestures: an exploratory phenomenology of gestures and their implications for being-in-the-world. In Cherished, Beloved and Most Wanted (2009), Cummins pairs an original Victorian photo album with a collection of found mug-shots from between 1920 and 1930 [31]. Here, Cummins represents an implicit violence—the unknown crimes committed by the subjects of the photographs. The book embodies movement, as the imagined violent gesture is placed in opposition to the stillness of the subject—in profile on the verso page and straight—on in the recto. The reader's experience mirrors the implicit gesture of the prisoner; as the page is turned, the person in the portrait turns slowly to face the camera. This gestural awareness is supplemented by the marginalia of Victorian flowers on each page, which intertwine and therefore necessitate a fluid and circular visual gesture in opposition to the angular imagined movement of the photographic subject and their imagined act of violence.

Figure 3. Maureen Cummins, Cherished, Beloved and Most Wanted. 2009.

<20> In this book, Cummins represents an experience of violence with a subdued gestural consciousness that serves to subtly amplify the experience of the content. The work is also particularly interesting with regard to the notion of the memorial, as the traditional photo album form becomes the site of remembered, re-performed violence. Here, the conscious gesture of memorialization is for the perpetrators of violence rather than its victims, but similarly imbued with a kinetic reading experience and implied violent gestures.

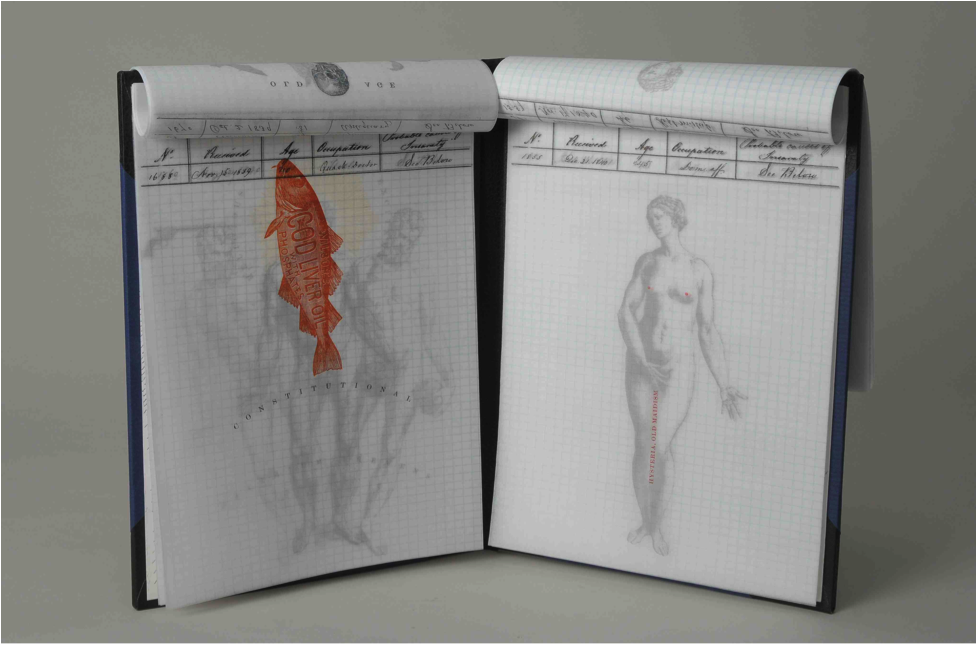

<21> Cummins's Anatomy of Insanity (2008) represents a compendium of psychiatric patients in the McLean hospital between 1819 and 1843 [ [32]. Fragile, layered pages represent the images and descriptions of causality for patients. The side of the text representing male patients is littered with diverse images and causes of insanity, while the female diagnosis is consistently described by a word associated with gendered afflictions, often "hysteria" or "menstruation," inscribed in red type between the woman's legs [33].

Figure 4. Maureen Cummins, Anatomy of Insanity. 2008.

<22> As in some of the Al-Mutanabbi texts, blood is allowed an independent gesture that grotesquely parallels the gesture of reading the text. As the reader peels back the layers of pages, the blood continues to flow downward. Cummins's work attends carefully to diverse incarnations of gestural violence and gestural reading, and the relationship between structural form and subtly violent content is consistently well balanced, neither overpowering the other. Accounting (2011) contains subtle formal choices that shape its content: physical violence is made experiential by attention to the gestures of reading and writing [34]. The work features first-person accounts of the Triangle Factory Fire of 1911 inscribed in a ledger book from the same year. Cummins draws attention to the gestures of writing, crossing out text and self-editing, as well as to the representations of gesture in the text. The gesture of reading is contained by the verticality of the book and the fact that it is impossible to open each page to more than 90 degrees, which mirrors the prevailing gestures of entrapment in the content: "The elevator started to go down. The flames were coming toward me and I was being left behind. I felt the elevator was leaving the ninth floor for the last time. I got hold of the cable and swung myself in." As well as attending to achieved movement, Accounting draws attention to the confines placed on movement. By interacting with the form of the book, the reader experiences a feeling of entrapment that mirrors the experiences of those trapped in the building during the fire. The gestural memories of the text constitute a performative memory enacted by the subjects of the book as well as by gestures, both imagined and real, of its reader.

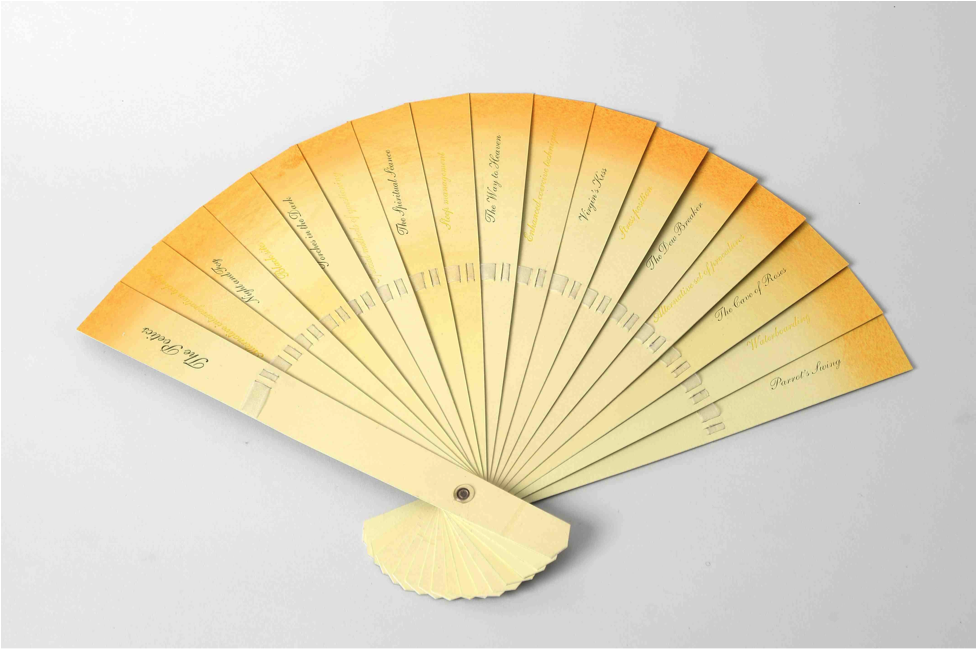

<23> The Poetics (of Torture) (2011) is perhaps Cummins's most powerful work regarding the gesture of violence [35]. In this piece, Cummins inscribes euphemistic terms for torture acts on the body of a fan. In opening the fan in one direction, the words are layered, alternating between orange and more obscure yellow on a yellow background, progressing through both mawkish and understated euphemisms for torture, including: "The Spiritual Séance," "The Dew Breaker," and "The Cave of Roses" interspersed with "Special methods of questioning," "Black sites," and "Waterboarding," all in delicate, ornamented typeface. On the other side of the fan, lines in gray on black on every other slat read "of torture / euphemisms / related to / acts of torture / widely by used by / repressive regimes / in countries such as / Iran, Haiti, Vietnam, Nazi Germany." On the intervening slats, in nearly the same color as the background, it is just possible to make out the words "and more recently the United States of America." In the gesture of opening the fan and reading the words, there is an inevitable progression as each fold reveals more text. The reader scans through a catalogue of hidden, euphemistic torture acts concurrently but in stark contrast with the revelatory gesture of opening the fan. The connotatively feminine and coquettish use of the fan as a material object is striking in its opposition to the violent gestures written on it.

Figure 5. Maureen Cummins, The Poetics (of Torture). 2011.

<24> This work in particular troubles the boundaries of public/private and intimacy/performance dichotomies. Private, hidden actions are translated to an object of social, performative function, and both gestures move into a space that is both intimate and violent: performative and euphemistic. Though the interaction between text/image and materiality of artists' books contribute generally to this effect, the most significant aspect of the texts for the relation to violence and memorials is the intimately tactile quality of the works. And, in the structure of many artists' books, there is a sense that nothing is held together, least of all the human body, and that the textual body could slip from your hands at any moment. The book might be damaged, the gestures it represents may fade from memory, and the gestures that constitute the performance of reading the artists' book may elude a place in the archive even as they remain.

<25> Like archives of live performance, artists' books are sites of intimate, but often problematic, intersection between the material document and the performing body. Artists' books self-consciously operate on a continuum that constantly re-negotiates spaces of presence and absence—of maker, subject, reader, material document—in the same manner as other gestural arts. The individual gestures of making or reading an artists' book are similarly transient—the gesture of unraveling a string or accessing an accordion fold disappears even as it occurs and, if we consider these gestures to be units of a performance, the overall performance can never be seen, accessed, or archived in the same way twice. Still, artists' books constitute a distinctive material, documentary form in which the ritual or performative gestures of access allow for a continual, if continually different, preservation of the moving body through repetition. Artists' books may further function as a potentially effective model for archival practice and a method thorough which to archive gestural art forms like dance and theater. If the archive itself can facilitate an intimate, gestural relationship for its reader, the gestures of the original performance may be more successfully preserved and the gestures of performance inscribed on and around the body of the book.

<26> Archival studies, literary studies, and contemporary culture have all in some ways lost their gestures, and what Agamben establishes as the

natural reactions of obsession and treating each gesture "as a destiny" may be the critical paradigm necessary to reclaim productive readings of the body

in motion [36]. Gesture is inscribed on every body from infancy and incites the most artistic and

imperative of human rituals—the experience of intimacy, the marking of significance by ceremony, and the production of all modes of art. By drawing this

developmental psychology formulation through other theories—archive, performance, communication—and more significantly through artistic texts or art

objects themselves, it is possible to come to a newly embodied way of reading movement. This attention to movement spans diverse incarnations of gestures

in texts as well as reaching outside of the body and temporality of the text—the gestures of making, reading, and otherwise interacting intimately with

artworks. As well as allowing for a particular kind of engagement with the intersections of gesture, intimacy, and violence in contemporary artists' books,

focused attention to gesture may also move toward a more expansive understanding of the spectrum from gesture to performance, from presence to absence, and

to the archive as a gesturing body.

[1] Giorgio Agamben, "Notes on Gesture" in Means without End: Notes on Politics, trans. Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 53.

[3] Marcia B. Siegel, At the Vanishing Point: A Critic Looks at Dance (New York: Saturday Review Press, 1968), 1. See also Herbert Blau's Take Up the Bodies: Theatre at the Vanishing Point (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982) for a canonical discussion of disappearance and the archive in performance studies.

[4] Richard Schechner, Between Theatre and Anthropology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985), 36.

[5] All artists' books discussed here are from the University of Denver's Fine Press and Artists' Books Collection. Special thanks are due to Kate Crowe, curator, for her kind assistance in selecting and working with the artists' books.

[6] For useful histories of the form and its antecedents, see: Johanna Drucker The Century of Artists' Books (New York: Granary Books, 1995); Stephen Bury Artists' Books: The Book as a Work of Art, 1963-1996 (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1995); Johanna Drucker The Visible World (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994).

[7] The question of reproduction is often at issue in definitions of artists' books. Is something lost if it is produced in a numbered edition? Must the artist who conceived of the book be involved in every aspect of its creation? We might consider this issue in relation to Walter Benjamin's concept of "aura" in "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." Though reproduction is not a central issue here, it will be useful to consider the extent to which reproduction/originality matters in the kind of material, performative aura of the artists' book.

[8] Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria: Book V, trans. Donald A. Russell (Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, 2001), 119.

[9] See James R. Knowlson "The Idea of Gesture as a Universal Language in the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries," Journal of the History of Ideas 26, no. 4 (1965): 495-508 for an overview of the range of seventeenth and eighteenth century rhetorical attitudes toward gesture as a universal language; Adam Kendon, "Gesture" Annual Review of Anthropology 26, (1997): 109-28 for a brief, comprehensive discussion of the history of gesture; Nicla Rossini, Reinterpreting Gesture as Language: Language "in Action," (Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2012) for an analysis of the history and current state of the role of gesture in the field of linguistics.

[10] Alicia Bailey, interview by Zach Wolfson, Beyond the Gallery. Infusion5 Web Television, April 10, 2014.

[11] Vilém Flusser, Gestures, trans. Nancy Ann Ross (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

[12] Ellen Dissanayake, Art and Intimacy: How the Arts Began (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), 6.

[13] See also Stephen Malloch and Colwyn Trevarthen, eds., Communicative Musicality: Exploring the basis of human companionship (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009) for further discussion of the significance of rhythmic and gestural communication to human experience, specifically the development of infant gestures into attachment patterns and ritual experiences in adults.

[16] This idea of dialectical simultaneity is a recent and notable development for gesture theory. David McNeill, particularly in Gesture and Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), is credited with bringing language and thought into a synchronized dialectical relationship. Most work in this vein has focused either on the way gesture reveals thought or the way gesture influences thought and speech. McNeill's work emphasizes a reciprocal, real-time experience in which gesture and language simultaneously inform each other. See also Shaun Gallagher's How the Body Shapes the Mind (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[17] See Drucker, The Century of Artists' Books, 309-14 for a discussion of artists' books as performative and conceptual art.

[19] Peggy Phelan, "The ontology of performance: representation without reproduction" in Unmarked: the Politics of Performance (New York: Routledge, 2003), 146.

[20] See in particular "Performance Remains" Performance Research 6, no. 2 (2001): 100-8 and Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (New York: Routledge, 2011).

[23] Jane Kenyon, "Notes from the Other Side," in Constance (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 1993), 59.

[25] See Joseph Roach's Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996) for a compelling interdisciplinary account of the intersections among gesture, performance, memory, and the funeral as a space of performance.

[26] Beau Beausoleil, "An Inventory Of Al-Mutannabi Street: A Call to Book Artists," The Al-Mutannabi Street Coalition, accessed 20 June 2015, http://www.al-mutanabbistreetstartshere-boston.com.

[27] Christine Kermaire, Resilience of Al-Mutanabbi Street (Charleroi, Belgium: Christine Kermaire, 2011).

[28] Christine Kermaire, Memory of Al-Mutanabbi Street (Charleroi, Belgium: Christine Kermaire, 2012).

[30] Bonnie Thompson Norman, Remember: people of Al-Mutanabbi Street, embellished by Jill Alden Littlewood (Seattle: Windowpane Press, 2011).

[33] Though the gender of the book artists considered here is not central to this argument, it is worth noting that, as Johanna Drucker argues, "the space of a book is intimate and public at the same time; it mediates between private reflection and broad communication in a way that matches many women's lived experience. Women create authority in the world by structuring a relation between enclosure and exposure." "Intimate Authority: Women, Books, and the Public-Private Paradox" in The Book as Art: Artists' Books from the National Museum of Women in the Arts, ed. Krystyna Wasserman (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), 14.

[36] Giorgio Agamben, "Notes on Gesture" in Means without End: Notes on Politics, trans. Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 53.