Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 1

Return to Contents»

To Show them and to Share Them: Maureen Cummins, Archives, and Book Arts / Katherine M. Crowe, and Maureen Cummins

<1> The University of Denver (DU) Special Collections and Archives has been building its Fine Press and Artists' Books Collection since 2004, largely in collaboration with faculty from academic departments in the arts and humanities. In 2013, the University Libraries hosted artist Maureen Cummins for a lecture about her work as an artist. Afterward, Maureen agreed to have a conversation with Curator Kate Crowe about her process for incorporating both archival and found materials into her art. The two discussed Maureen's artistic beginnings, her transition to working as and thinking of herself as a fine artist, and her thoughts on the inclusion of archival and found materials into her work.

<2> The resulting essay contains excerpts of the conversation between Cummins and Crowe, edited for content and clarity, interspersed with observations from literature about archives, fine arts, book arts, and the ability of material culture and other residues of human activity in archives and art to evoke living and lived histories.

The Materiality of Archives

"That's the fascination of archives. There's still a bodily trace." - Susan Howe (Howe, 2012)

"There are a lot of reasons behind my decision to work with found material and archives: economics, an aesthetic love of the material, and a certain kind of playful possibility of all of these different layers coming together. I've always felt spiritually drawn to found materials, even before I considered that I might make art with them." - Maureen Cummins

<3> Poets, artists, philosophers, and even researchers have written and spoken extensively about their personal and aesthetic relationship to archival material and to "the archive." "The archive" has been thought of and written about in a multitude of ways, from a variety of perspectives, many of which do not reference the literal "archives," comprised of organizational records and personal papers, housed in government storage facilities and universities - though many refer directly and indirectly to the material qualities of archives and archival material. In an interview with the Paris Review in 2012, the poet and visual artist Susan Howe speaks about how paper can become a medium, a "permeable barrier" between the artist and the creator of the material (Howe, 2012). Maureen Cummins' works also use archival material to bridge these two worlds. Cummins' first editioned book using printed archival matter, Checkbook, came about as she was struggling, both financially and creatively, with her work as a fine press book artist. She recalled that the decision to use printed archival material was very much a "fated moment" - the result of a regular visit to the flea market, where she would go to "escape" the tedium of printing. However, on that particular day, Cummins recalled:

"I happened upon a woman who had a crate-full of these turn of the century checks, literally thousands of them. They were so beautiful...I asked her: 'How much is that crate,' and she said: 'Five dollars.' I just knew, as soon as I saw that crate of paper - something clicked and I realized I didn't have to spend thousands of dollars on paper - this was my paper. It just all came together."

<4> Cummins' interest in the checks began with a personal draw to the aesthetic qualities of the checks, magnified by her life circumstance as a struggling artist. In addition to her financial struggles, she felt increasingly disconnected from her fine press book work, due both to financial pressures and creative dissatisfaction. She was taken with the physical qualities of the checks; she "loved that there were red serial numbers on each check" which reminded her of page numbers. Their physical nature provided a direct connection to the world of banking and high finance, and a way to comment on the reality of being a young artist with no financial or institutional support. The materiality of the checks also led her to contemplate the meaning of the word used to represent them; she began to turn over the word "check" in her mind, "wondering about its origins." When she looked the word up in the Oxford English Dictionary, she found that "there were close to 30 definitions of the word "check" and they all had to do with being put down, or kept down, or prevented, or stopped...and those definitions became the text of the book." The process that she used for this book became the process that she has used for her other, subsequent editioned artists' books that incorporate found or archival materials. She has found since that this rarely would begin or end in the same way:

"It's a process of curiosity and of not exactly knowing where I'm going, of faith, of experimentation, of waiting for something to come, of meditating on some aspect of the material that inspires me, whether I'm starting from a piece of text, or whether I'm starting from something material. It goes both ways - sometimes I will find an object, or a book, or paper, or, in one case, it was a series of glass negatives, and then I'm looking for the text. And in other cases, I find some incredible text, and I'm looking for a way to house that text."

<5> Cummins also spoke of the the quality of "alive-ness" that archival materials have. For her,

"Working with found or archival objects is almost magical or religious. I feel that there is an energy and a spirit inside materials and objects that our ancestors made, held, read, worked with, lived with, and touched over and over for years or decades or even hundreds of years, before they came into our hands. I feel very much the way primal cultures feel about these inherited, ancestral materials."

<6> This quality of something inherent in archival material beyond its research utility or documentary value is a concept that also emerges in the professional archival literature. Professional archivists typically use the terms "intrinsic value" to describe these material qualities: "The usefulness or significance of an item derived from its physical or associational qualities, inherent in its original form and generally independent of its content, that are integral to its material nature and would be lost in reproduction" (Pearce-Moses, 2005). This somewhat nebulous, subjective-sounding quality has frustrated archivists - like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart's famous "I know it when I see it" assertion in his ruling on a 1964 pornography case, it seems to be based almost entirely on "self-referential confidence" rather than an objective assessment of the materials at hand (Gerwitz, 1025). However, as Justice Stewart also stated in his opinion, he felt that he was "trying to define what may be indefinable." (Gerwitz, 1025). Cummins' response to a question about the difference between works that use original historical materials and those that utilize reproductions suggests something similar - an indefinable quality that is, nonetheless, significant:

"A curator once asked me, 'Would it be the same if you re-printed one of these books that are printed on actual found ledger pages, or actual found diary pages?' My answer to that, emphatically, is that it would not be the same. It's not to say that I wouldn't do it, because there is a certain use in replicating an idea so that a large number of people can be exposed to it, but it would not be the same."

Archives, Memory, and Trauma

"The archive-the good one-produces memory, but produces forgetting at the same time." - Jacques Derrida, seminar on the work of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission at the University of the Witwatersand, 1998 (Harris, 2005, 132)

"In some cases, the very act of telling a story can be inflammatory. In these cases, it's not about what is told, but the fact of it being told [...] For example, I did [a project called Divide and Conquer] on lynching, and I remember having a conversation with an African-American colleague about the project. I said something about white Americans needing to know this story and she said 'But my people want to forget it.'"

- Maureen Cummins

<7> In his 1995 essay "Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression," (translated in 1996 from the French Mal d'Archive: Une Impression Freudienne) the philosopher Jacques Derrida uses the concept of Freud's "archive" to meditate on the concept (not the literal "archives" as place/institution) as a place of violence. (Derrida, 1996, 12) Derrida expanded on this concept in correspondence with Verne Harris, the archivist for the papers of Nelson Mandela, calling the work of archivists "a work of mourning." (Harris, 2005, 132). Harris also suggests that the primary challenge that Derrida poses to archivists is - "how can we make our work a work of justice?" (Harris, 2005, 137). It would be equally true to speak of Cummins' work with archives as a book artist as being part of that same process of "mourning" and a protest over historical injustices. Many of her books contain archival materials that document the stories of individuals who, due to the intersecting issues associated with being a particular race, class, gender, or a combination of the three, have faced social stigma, violence, and oppression, or bring to light the ugliness and injustice of the actions of the dominant group. Cummins' works bring together and juxtapose words and imagery, using the book form, to bring these narratives to life:

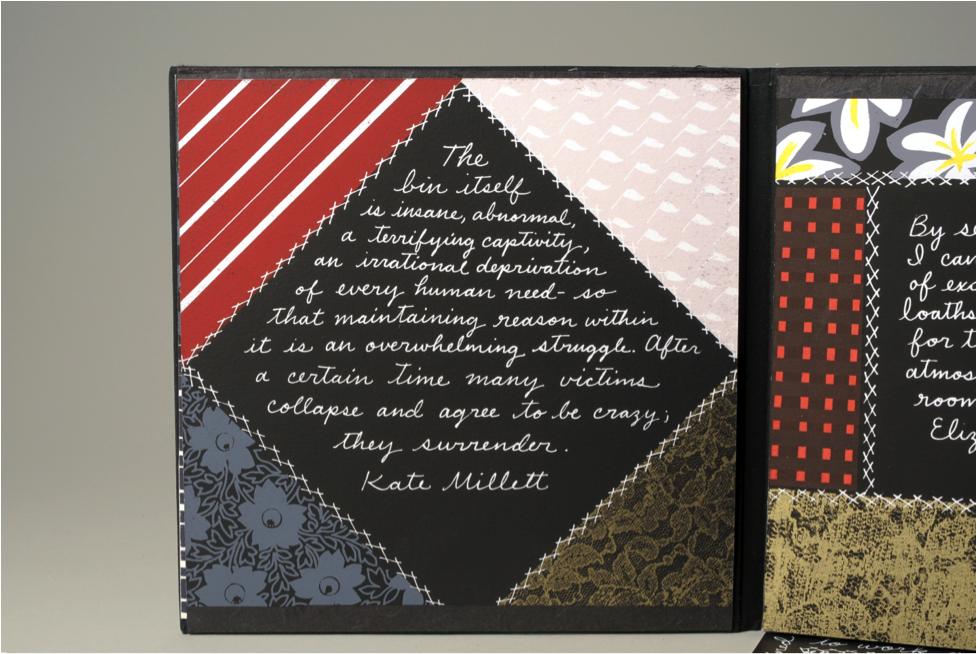

"[How I've chosen to bring together words and images in my art] has not been by chance, and it's not merely playful, it's really a function of how I see the world, which has only been magnified and reinforced by my work with historical materials and narratives, where there is often a beautiful exterior hiding something very ugly. In terms of my work, the most immediate example is "The Business is Suffering," which uses letters written by slave dealers to their customers and who are buying and selling stock - people - and the language in those letters is so beautiful, gentlemanly, elegant, and high-minded. I am consciously trying to show the juxtaposition between things that are ugly and things that appear to be beautiful, not to mistaken with images in the world of suffering and of pain that are made to look appealing. To me, that is the essence of pornography - to make something that is truly ugly appear to be beautiful."

<8> Cummins' work Accounting follows this same line of thought; the work documents the mainly female victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire from the perspective of a (presumably male) accountant, documenting loss of life, and money, through a fictionalized reproduction of a 19th century ledger. The ledger utilizes authentic archival elements - the first-person, hand-written notes and the overprinted first-person accounts - but does so in a way that can puzzle the viewer, who does not and cannot know what in the ledger is real and what is not. Far Rockaway uses one side of a correspondence between two closeted male lovers in early 20th century New York, tracking the relationship from its passionate beginnings, to anxieties about being discovered, to its eventual unraveling. The letters were discovered during one of Cummins' visits to the flea market. In her interview, Maureen recalled seeking out the executrix of the estate of the man, "Jules," whose letters she had in her possession, asking if she could publish them as an artists' book, and having the woman only agree to have them published pseudonymously. Cummins said of the project: "In a way, it was so much more apt, because it showed that, even 100 years after this clandestine love affair, when these two men were in the closet, they still, in the 21st century, had to be closeted. So that in a way was so perfect."

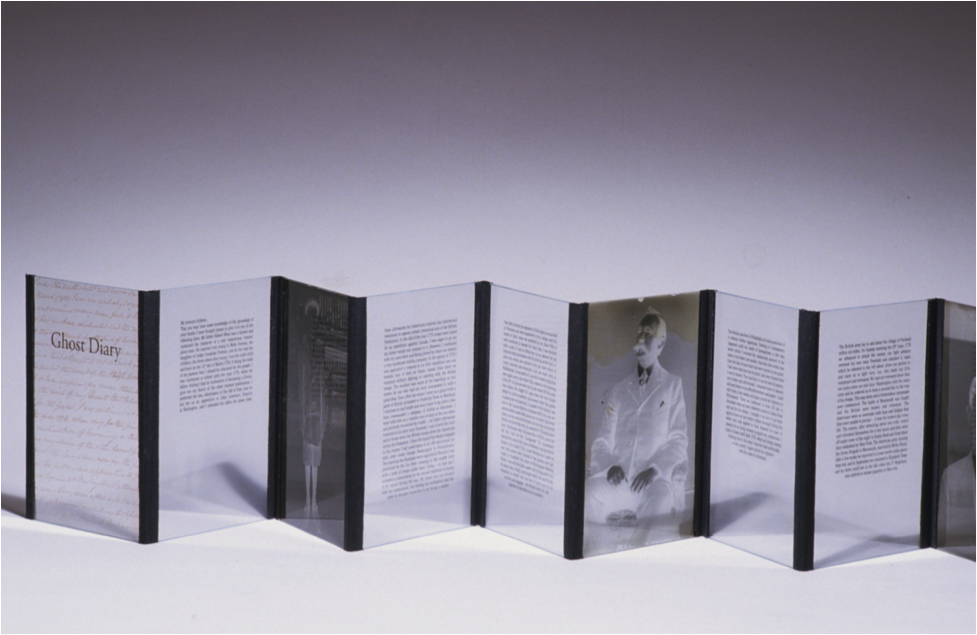

<9> When asked if some of the people whose narratives appear in her books would want their stories told, Cummins touched on a significant ethical aspect of both artistic and archival processes when working with other people's narratives and material: how and when to maintain privacy, especially when the story being told brings to light truths that are controversial or dark. As with archivists, how the story has come to light - through public record, private donation, or serendipitously discovery in a flea market - is significant. Maureen "[feels] perfectly fine" printing testimonies of individuals targeted by the Ku Klux Klan in her book Divide and Conquer, as they had already been part of the public record, but handles each instance of private biographical artifacts on a case by case basis. For her book Ghost Diary, the text of a letter that Cummins used was clearly only meant to be read by the wife and children of the man who'd written it. When Maureen met one of the man's descendants later on, she noted that:

"There is a tendency to think "this is all behind us," and it's not - it's living history! The descendants...are still here, [and] that...history is still being written. It's deeply, exquisitely sensitive. It's also what motivates me to deal with the stories in the way that I have - over the years, I've become aware of just how potent this material is."

<10> The tension of living descendants' feelings about artistic works resulting from their ancestors' materials almost halted the creation of the Far Rockaway book. When Cummins sought out the appropriate family member to seek permission to publish the letters, she found that the executrix of the estate of the wife of one of the men, a woman in her eighties, rather than 'falling in love" with the project as Maureen had hoped she would, became very concerned about the "hoopla" that this information being made public might cause.

<11> Cummins also puts a considerable amount of thought into what she feels would have been the wishes of the creators of the materials, as they are often not documented and are therefore largely unknown. In these cases, when she is printing "something very private, something that wasn't meant to be read by anyone other than who received it," it becomes a judgment call. Susan Howe has spoken of a similar process of interacting with archival materials and their creators, which she refers to as "telepathy" (Howe, 2014). Cummins' Far Rockaway project suggests a similar kind of connection, as it required her to spend between five and six years with the letters of "Jules," (the pseudonym given to one of the correspondents). By the end of the process, she felt as though she knew him, and that she "could even feel how much he loved the idea of me allowing the love of his to live on." At the same time, she has looked back at some of her earlier work and thought:

"I'm [not so] comfortable with the stories I've told or how I used materials. I feel there is a very, very strong line between a story that I have the right to tell, and one that I don't. I don't have a right to tell a living person's story that was told to me in confidence, or a story that that person would not want to be told. In terms of working with the dead, I believe we still have ethical obligations to those who are no longer living. It's is a difficult choice and what I end up doing is trying to really connect with this person, and who they are, their spirit and their motivation, to try to discover if they would want this story to live on in some larger way."

<12> Cummins' work with her late mother's diary reflects this tension as well. She now says of the diary that it is "the most important piece of found material ever" in informing her process as an artist and the work itself, but even in work that is almost autobiographical, she has had to draw upon this same kind of connection with her mother to attempt to understand how she would want her story to be told after she could no longer be explicitly questioned.

<13> Archivists wrestle less with this specific ethical question, largely because records or papers that have come to archives have come as the purposeful gift of either the creator of the record, their family member, or executor, so there are generally fewer questions of what the creator would have wanted to be made available. A related question for archivists that is less talked about outside of archival literature - but which should be of concern to artists, poets, activists, and others concerned about the preservation of the historical record - is the issue of what of the archival record is retained by archivists, and how it is made accessible to researchers. As the twentieth century has progressed and the production of records and text documents has ballooned, archivists have wrestled with how to decide what to keep. At the same time, the archival theories which guide professional practice have not kept pace with the reality of the massive increases in the amounts of records that archivists now have to make decisions about - what to keep, and what not to keep.

<14> The late Terry Cook, a Canadian archivist who wrote extensively about the appraisal of archives for retention, as well as issues of social justice, memory, and identity in archives, has said: "The archive itself [has been] perceived as a 'natural' accumulation…[and] not interrogated as problematic...but the choice [about what the archive is made up of] is by no means value-free." (Cook, 2011, 176). Cook, and others, have worked to develop a theory of "macroappraisal," or "total archives," whereby archivists "focus on the mechanisms...or processes in society where the citizen interacts with the state to produce the clearest insights about societal dynamics and public issues, and thus societal values." (176). This approach is significant because it represents a shift toward a "two-way discursive framework," "reflecting multiple voices, and not by default only the voices of the powerful." (177). As the work that Cummins and other scholars and artists have created using archival materials often seeks to expose the voices of those marginalized by society, it is critical that they, and others interested in the preservation of the record of the "broad spectrum of human experience," be aware of and critique the decisions that archivists make, to ensure that all work by both the users and the providers of archival material is in service of this overarching goal (179).

Archives and Identity

"[The] archive…[is] at once close to us, and different from our present existence, it is the border of time that surrounds our presence, which overhangs it, and which indicates it in its otherness; it is that which, outside ourselves, delimits us." - Michel Foucault (Foucault, 1972, 147)

"The most important element in all of my work in book arts is my mother's diary. I received her diary during the period of time when I was making my first artist books, and it was and has been the most important piece of found historical matter, ever, for me. It changed both my life and my art overnight. Talk about an archive on fire - it changed my perception of my childhood, how the world works, my conception of myself. I became much bolder. I wasn't just going to make beautiful decorative books anymore." - Maureen Cummins

<15> Cummins' personal example above shows how not only archival material connected to her past and her mother's past has shaped her work as an artist, but also how it has shaped her conception of herself. As Michel Foucault has noted, the archive "delimits us" - it is too close to us and our conception of ourselves for us to not be defined by it. As Cummins says above, her mother's diary is omnipresent; it factors into all of her works, even those that do not explicitly reference it:

"The act of reading her diary, and connecting to my past and to her experience, that was a huge part of my wanting to work with found printed matter, wanting to go directly to sources, to find stories that were alive, and original, and authentic. I was so inspired by her story, and all the revelations that it brought to me about my own history. The experience of working with her diary has informed every project since then, no matter what the subject matter. Not a single one of my artists' books would have come about had I not had that very potent experience of connecting to my mother through this archival material."

<16> The use of archival or material culture objects in the construction of personal identity appears in the academic literature in sociology, philosophy, and anthropology, but is generally absent from the archival academic discourse. Despite the absence of this conversation in archival literature, sociologists Andrew Weigart and Ross Hastings rely heavily on language from the cultural heritage world to describe the role of the family and shared "archives" in the construction of the self: "not many members of society establish their own religious, political, or economic institution, but nearly all marry and become parents...many biographies are anchored in the family" (Weigart, 1977, 1175). Weigart and Ross posit that "while institutions...collect and retain only what is relevant to its own purposes...the family has a special archival function as a repository of identity symbols which compose a biographical museum...for an individual's personal and social identities." (1175) This "archival function…provides proof and documentation of continuity of self," (1175) and "is a major reason why family identities and relationships are central for an individual's biography" (1176). As Weigart and Ross note, "How else can an individual sustain a uniquely personal living memory of who he or she was and is?" (1176). Rather than focus on the construction of personal and family identity, archival discourse instead focuses on archives as sites of the construction of social and cultural identity, and focuses primarily on archives and archivists' need to critique their perspectives, methodology, and roles in the construction of cultural identity.

<17> Though the concept of the archives as a means of constructing personal identity is not one that appears in the academic archival literature, several archivists have written extensively about the role that archives play in constructing social and cultural identity; most notably, Terry Cook and Elisabeth Kaplan. Kaplan, in a widely cited 2000 article "We are What We Collect, We Collect What We Are: Archives and the Construction of Identity" uses the complex history of the founding of the American Jewish Historical Society, the "oldest extant ethnic historical society in the United States" to tease out the socially constructed nature of identity, and the role that archives play in "[preserving] the props with which notions of identity are built…[and] in turn notions of identity are confirmed and justified as historical documents validate their authority" (Kaplan, 2000, 126). In all of their writings on the subject of archives and identity, Kaplan and Cook remind their audience - largely archivists - that the archivist's role in preserving and providing access to archival materials is inherently subjective and inherently, as Derrida would have it, political. Kaplan is quick to point out that academic writing about identity was so pervasive up through and into the period she was writing for noted scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. to call it, in 1992, the "cliché-ridden discourse" (145). She notes that, despite this, archivists writing about the same subject, with the exception of Terry Cook and several of his co-authors, rarely mined, joined, or interrogated their role in either the discourse or the process of identity creation.

<18> Kaplan's example of the AJHS to illuminate the complexities of archives and archival material in the construction of identity is a compelling one, showcasing the role of the archives in the eyes of many of the founders of "ethnic" historical societies and other like organizations. Founded in the late 19th century, the AJHS' founders - all men, from many countries of origin and citizenship statuses - were united in a shared, multi-faceted goal: to document, affirm, and present to the outside world their community's identity as American Jews - not just as Jews, not just as Americans - as American Jews. Kaplan uses a condensed narrative of some of the meeting minutes of some of the first meetings of the AJHS to show the significance of the historical society's mission to its founders. The urgency they felt to establish the society came as a result of pressures from both without and within - the structure of the "old World" no longer imposed "Jewishness" on them, and at the same time, an increase in xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States led American Jews to want to present a cohesive, un-threatening and very American identity to those who might question their patriotism and loyalty (135).

<19> The mission of the budding historical society was the subject of much debate - some thought that the purpose was to gather historical documents and preserve them for researchers; others argued that the historical society should publish essays to show the value that American Jews had to American society. In addition, the scope of the collection (and the community it documented) was not easily agreed upon. Should the society document the recent, and more religiously observant Eastern European immigrants, Zionism, or other topics complicated the ability of the founders to present a cohesive, shared identity? If so, what questions might this provoke about the patriotism of American Jews? The early acquisitions and meeting minutes indicate that early collecting focused on "firsts," (first Jews to hold office, participation in voyages of discovery, etc.) and other like historical facts which would solidify the idea of Jews as "Americans...who happened to be Jewish" rather than Jews who happened to live in America (142).

<20> Maureen Cummins' work as an artist is noteworthy, not only because she mines flea markets and collections in institutional archives as a means of commenting on our shared, constructed identities, and in many cases, our shared cultural amnesia, but because she does so while remaining in continuous engagement with her own familial, personal archives as a way of sharing her own personal identity through her artwork.

The Magic of the Handmade

He is the greatest artist, then,

Whether of pencil or of pen,

Who follows Nature. - Kéramos, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

"There is the pure beauty of materials that were made by hand - in a much less mass produced fashion. That's a loss that I really mourn, so I just wanted to surround myself with these materials, and show them, and share them." - Maureen Cummins

<21> Cummins' work as an artist, and training as a book maker, has focused on art forms that require some aspect of hand-making on her part - first, illustration, then the making of fine press books, then the wider exploration of the varying forms required by her artists' books, including: bookbinding, printmaking (letterpress and other types), metalworking, darkroom and other photographic processes, etc. Her focus on artistic processes that require hand-making and natural materials is intentional:

"I mourn the death of so many art forms that involve materials that are made entirely or at least in part by hand, such as darkroom photography or letterpress printing. In these art forms, you are working with materials that you touch - actual lead type or processing chemicals. It is a very elemental process, it is close to nature - in some cases we are actually making these materials. As an artist, to not have a connection to where your materials came from becomes very, very abstract and I think, unnatural. Human beings were meant to be connecting with nature, and making things. We're supposed to be using our hands."

<22> Cummins' focus on the significance of the beautifully handmade, specifically in reference to the making of fine press books, has a long tradition beginning with private presses created by some of the leading lights of the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain in the 19th century - most notably, William Morris and the Kelmscott Press. Though Cummins shared a philosophical kinship with many of the private press founders - a love and a belief in the importance of the handmade, specifically in reaction to the mass-produced - she realized as her fine press work progressed that she had little in common with that history and the day-to-day realities of the work. She recalled that:

"[Fine press work] is of a certain class, heritage, a certain economic tradition, and I didn't fit into that - I was a [female] starving artist trying to work in this field that was part of the legacy of [wealthy] gentleman printers. [In contrast], I remember...spending a thousand dollars on paper, and not having any food to eat in my refrigerator."

<23> Despite the recognition that fine press work was not for her, she retained a love and an affinity for artistic processes that required her to work with her hands, and with books as a medium. The medium of book arts has largely allowed her to create works that she feels satisfy the requirements she has as an artist. Still, she has noted that book arts have a somewhat uneasy place in the fine arts world. The world of fine art, she feels, is somewhat more open to her relatively dark subject matter, if not necessarily the medium she works in:

"I see more and more books in museum and gallery shows, but not exactly a tidal wave of them and it's surprising because they are so alluring - people really do love to look through them. I'm in a gallery show right now, and [of the] three books in the show, mine is the only one you can page through. Maybe there is resistance - not on the artist end of things, but on the art world end of things, being willing to allow this in - perhaps it is too democratic a medium."

<24> The slow, if not necessarily steady, acceptance of the book arts as a medium that is of interest to the fine arts world has occasionally caused Cummins to question if there might be another way or medium for her to work in, but she continues to return to processes that allow her to work with her hands, and specifically to the book form:

"The conceptual heart of my work is that I am using...the book form to comment on books and...the social construction of knowledge. [This commentary] doesn't exist in the fine press world, that's not what it's about - a book is a book, it is what it is. My only and sole interest in books is as a commentary on...what knowledge we hold up and what knowledge we suppress and so on. It's why I keep coming back to the book - on a certain level, I feel that I should be expanding out into the fine art world and making art that shows in galleries, but the book form is so perfect a vehicle for me to get across my concerns and to comment on how we end up thinking what we think."

Artists and Archivists

"What I love about university libraries is that they always seem slightly off-limits, therefore forbidden. I feel I've been allowed in with my little identity card and now I'm going to be bad. I have the sense of lurking rather than looking. You came in search of a particular volume, but right away you feel the pull of others." - Susan Howe, "The Art of Poetry No. 97," Paris Review (Winter 2012)

"I gave a presentation of my work in progress to the American Antiquarian Society curators and staff, showing books that I had unbound and reprinted. Someone told me after the presentation, 'There were all of these conservators in the back row, and when you showed the books you'd taken apart and overprinted on, they were horrified, they were gasping!'" - Maureen Cummins

<25> Maureen Cummins' work in book arts began in flea markets, but eventually moved on to working with archival materials in institutions like the American Antiquarian Society. She refers to the realization that "there were these major research archives...with millions of books, hundreds of ledgers, and they would bring artists in to use them" an "epiphany." The process of working with materials in these institutions was, by necessity, different from working with materials she had purchased and could unbind, surprint over, and otherwise alter to suit her conception of the work. She recalled that up until that point, she had worked with materials "very freely," and that the process of learning to work with curators and institution staff was somewhat challenging. In some cases, the materials were deemed "too delicate" to reproduce, and she had to alter her plans for the work to suit the available materials. Her work "Divide and Conquer" falls into this category - she had initially intended for it to include handwriting from some material in the AAS archive, and instead ended up having "to get imaginative" and use a typeface that was contemporary to the handwriting. Though the process of working with materials in an institution required her to work differently, she noted that "having those restrictions opened up my work in a way, because I had started to become formulaic, and having boundaries and rules and restrictions ended up being very freeing." Cummins' relationships with librarians and curators who collect her works has evolved over the years. Initially, she recalled that:

"There was a time when I was younger and kind of shy, and I didn't have a lot of connections with the curators themselves, and dealers were selling the books. Now it's really exciting to know just how many people see and use the books."

<26> Cummins' most recent book, "Anthro(A)pology," reinforced this feeling, as it required her to travel to multiple archives in order to mine their collections for inclusion in the book. During this trip, she observed that:

"I've been told by librarians that my work (and other contemporary book arts) is shown to multiple classes across the curriculum-not just art students, but students of creative writing, literature, black history, women's studies. I'm always so heartened to hear that."

Conclusion

<27> Maureen Cummins' choice as an artist to work with archival material within the book arts medium puts her in the company of many other visual artists and poets who have chosen to do the same. Like Jen Bervin, she has chosen to mine the personal papers of other writers and artists - Bervin with Emily Dickinson's envelope poems, and Cummins with her mother's diary. Like Susan Howe, she develops close, personal connections to the creators of the material she works with. Like both of these women, and many other artists who work with this kind of material, Cummins is not only able to present historical narratives critically, but in a way that causes the reader to engage with the material on a deeper and more intimate level than they would if they were presented with historical materials in an un-mediated way. She is able to uncover hidden voices, commune with them, and present them to the world so that whatever injustice was done to them in life can be known and seen, and that those who perpetrated these injustices may be held accountable. In this way, she answers Derrida's call for "the archive" to be not only a site of mourning, but a part of the process of working toward justice and healing.

Works Cited

Cook, Terry. 2011. 'We are what we keep; we keep what we are': Archival appraisal past, present and future. Journal of the Society of Archivists 32 (2) (10): 173-89.

Derrida, Jacques. 1996. Archive fever: A freudian impression. University of Chicago Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1972. The archaeology of knowledge: Translated from the french by A.M. Sheridan Smith. Pantheon Books.

Harris, Verne. 2005. 'Something is happening here and you don't know what it is': Jacques derrida unplugged. Journal of the Society of Archivists 26 (1) (04/01; 2015/06): 131-42.

Kaplan, E. 2000. We are what we collect, we collect what we are: Archives and the construction of identity. American Archivist 63 (1) (Apr 2000): 126-51.

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. 1878. Kéramos, and other poems.

McLane, Maureen N., and Susan Howe. Winter 2012. Susan Howe, The art of poetry no. 97. The Paris Review (203).

Pearce-Moses, Richard, and Laurie A. Baty. 2005. A glossary of archival and records terminologySociety of American Archivists Chicago, IL.

Weigert, Andrew J., and Ross Hastings. 1977. Identity loss, family, and social change. American Journal of Sociology 82 (6) (May): 1171-85.

Return to Top»