Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 1

Return to Contents»

Nature & Spirit: A Digital Lens of Gay-Male Culture / Brandon S. Gellis

Abstract: History is fraught with critical reactions toward homosexuality. Within the United States, response by the culture-at-large (mainstream culture) towards this sexual orientation underwent a radical transformation within the last one hundred years. Toward the beginning of the 20th century, homosexuality was deemed immoral and punishable by law, necessitating that most homosexuals remained closeted and forcing gay communities to evolve separately from, yet in parallel to, the culture-at-large. However, by the 1960s gay political organizations began publicly protesting the mistreatment of gay communities, and arguing for equal treatment and the decriminalization of homosexuality. Burdened by the mid-20th century art world's homophobic tendencies, gay artists of this time period embraced these political ideals, which sparked their development of bodies of work challenging traditional notions of sexuality, gender, love and eroticism. These early forays into expressing gay culture within mainstream art became foundational for digital and new media artists to gain critical voices, which enabled them to lash out at personal and cultural affronts.

Nature & Spirit: A Digital Lens of Gay-Male Culture explores how the culture-at-large (the mainstream culture) has specifically suppressed gay-male behaviors, simultaneously fueling the formation of support networks and popular gay characteristics (e.g. lingo & speak, art, camp and drag). Revisiting 20th century expressions of gay-male culture through 21st century new media practices, Nature & Spirit decodes and interprets the interplay of identity politics and biological politics in dialogue with biomimetic creative practices. Nature & Spirit begins with the identification of critical vectors by which the culture-at-large has critiqued gay men. With time gay men have remastered such criticisms, developing behavioral tools of empowerment and allowing for better incorporation of gay culture into the culture-at-large. Crucial to this discussion is an artistic series of hybrid work that have influenced discussions of sexual identity and biological politics.

Introduction

<1> Digital and new media practices have changed our modern artistic landscape. Nature & Spirit: A Digital Lens of Gay-Male Culture explores how 'the culture-at-large' has suppressed gay-male behavior, fueling the formation of support networks and popular gay characteristics (e.g. lingo & speak, art, camp and drag). Cultural datasets about gay marriage, constitutional gay marriage bans, sexual identity and Civil Rights era's interracial marriage bans gathered online, drive the digital media tools used for Nature & Spirit's creative visual explorations.

<2> Nature & Spirit is a visualization of biomimetic practices witnessed through emergent digital art methods. Calling upon the use of digital media technologies and open source, visual programming environments (e.g., Processing, Netlogo, Arduino microcontrollers, Max MSP, Microsoft Kinect, etc.), this creative exploration examines the logical, phantasmal (Harrell 2013) and imaginative media (Parikka 2012) approaches available to gay-male communities. Pulling inspiration from 20th century digital media, art and literature, Nature & Spirit addresses concerns of how gay-male communities may continue to become more accepted contributors of the culture-at-large.

Revisiting 20th century expressions of gay-male culture through 21st century new media practices, this exploration aims to decode and interpret the interplay of sexual identity and biological politics in dialogue with biomimetic creative practices. This conversation begins with the identification of critical vectors, or lenses - cultural & social dynamics, sexual stigma, scientific influences, predator vs. prey, homophobia, familial obligations, and historical persecution - by which the culture-at-large has specifically overshadowed gay-male communities. With time gay men have remastered such criticisms through the development of behavioral tools of empowerment thereby allowing for their better incorporation into the culture-at-large.

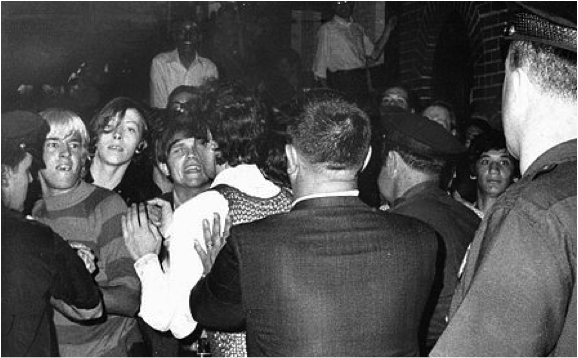

<3> Critical to this discussion of hegemony is the following art and literature review, and a series of biological and cosmologically focused creative explorations. In section 1, the influences of biological and political interactions are discussed through large and small-scaled explorations. Section 2 provides a discussion of contemporary history, art and literature and their influences on gay-male culture. Section 3 brings this discussion into the 21st century by exploring digital and new media art practitioners, who are also outspoken activists and educators. This discussion is accentuated by examples of imaginary media and speculative realism (and fiction) in section 4. All sections lead to the discussion ofNature & Spirit's culminating creative exploration and how my personal experiences and beliefs have informed this hybrid discussion.

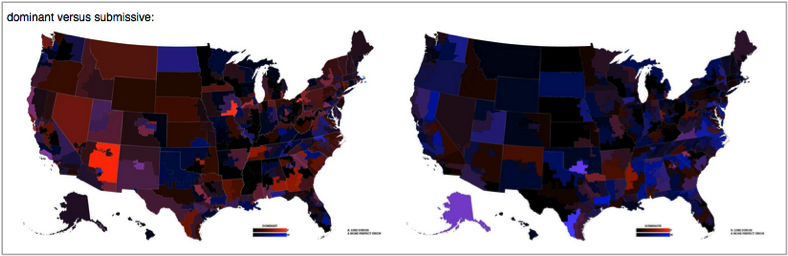

SECTION 1: Identity, Complexity and Emergence

<4> Central in much of this investigation is E.O. Wilson's thesis of eusocial species (highly organized animal societies) behaviors and how superorganismic systems are used to inform biological and social networks, like swarms and insect colonies. Integral to discussions of community and natural systems is complexity theory and occurrences of emergence. Complexity theory addresses scientific phenomena and theories through social biological systems, and considers relationships between all factions in a given system, or the ways in which multiple systems interweave, lending to the foundation and discussion of biological politics.

<5> Emergence provides fundamental structure and patterned ordering necessary throughout complex communities. Natural swarm systems, on the other hand, operate with an inherent sense of emergence and self-organization, as they are methodical in their synchronicity, need no top-down direction, and perfectly inspire the groundwork for digital media development. Nature & Spirit references how emergent digital media tools enable modern society's adaption to technology and mirror biological systems.

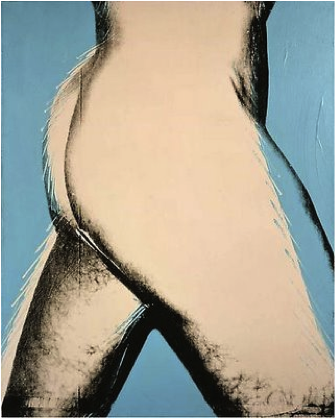

<6> Roberto Esposito discusses correlations between social and political dynamics of networked communities. Esposito argues that "By overlaying the legal and medical semantic fields, one may well conclude that if community breaks down the barriers of individual identity, immunity is the way to rebuild them, in defensive and offensive forms, against any external element that threatens it." However, he adds that too much immunity may cause "the sacrifice of the living." (Esposito 2013, 85) Ultimately the purpose of community is to support individualism while protecting the whole from outside harm.

Biomimicry and Digital Media

<7> This same level of complexity and swarm logic is present in the development of digital media and countercultural activist efforts. (Parikka 2010) As humans have taken over greater parcels of natural ecosystems, there has been a rise of human activity mirroring that of insect colonies. Biomimicry (and biomimetics) is the study and mimicry of nature's models and designs to solve human problems. "Consequently, if we see the key political and organizational agenda of contemporary technological culture as one reliant on the insect question, this begs us to look quite closely at how insects have been gradually integrated as part of the creation of media culture, key concepts of body politics, and the diagrammatic capture of 'animality' as an affect, an intensity." (Parikka 2010, 29) Following the example of swarming insects, counterculture activists often act locally and influence broadly. With the rise of social and digital media resources, a power shift has occurred making way for a divergence from the culture-at-large.

<8> Mirroring that of natural biological designs, the interplay of physical and digital media systems has afforded gay activists the ability to achieve a greater standing across conversations of (sexual) identity and biological politics. Activists celebrate a multidimensional opportunity to meet, collaborate and organize movements. In "Video, activism and the art of small media," Michael Chanan asserts that digital and social digital media provide activists with an opportunity to swarm out from the margins and interstices to strike against hegemonic powers. (Chanan 2011) He suggests that every activist movement having arisen in recent years has harnessed the Internet and supportive digital media to organize and propagate messages. Video itself is not a new resource for activists, but combining video and digital media resources has provided activists with the upper hand of immediacy and breadth.

SECTION 2: Gay Liberation

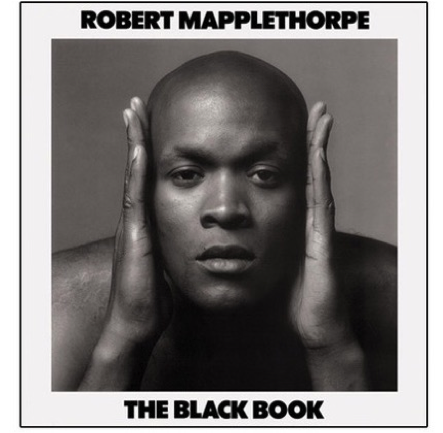

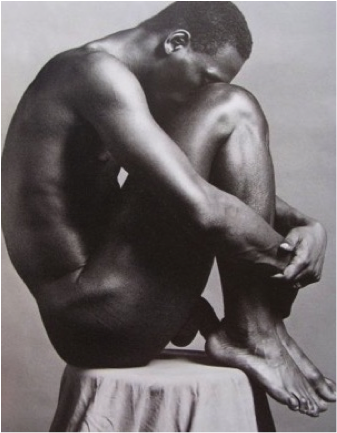

<9> The years from 1962 to 1966 is seen as the period in which the mainstream media 'discovered' the homosexual community. Major newspapers and magazines such as the Washington Post, the Denver Post, Life, Look, Time, and Harper's ran features on gay communities, gay meeting places and gay lifestyles." (Gidal 2008, 132) A major turning point for gay communities was the Stonewall uprising in 1969 (fig. 1). Counterculture activists brought gay culture out and into the open. The Stonewall Inn catered to drag queens, the newly self-aware transgender community, effeminate young men, male prostitutes and homeless youth. Police raids on gay bars were routine in the 1960s, but officers quickly lost control of the situation at the Stonewall Inn, attracting a crowd, and causing a riot.

|

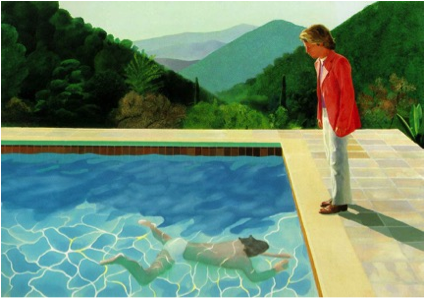

|

|

Figure 1: Documentation of The Stonewall Uprising, black and white photo, June 28, 1969 |

Codes and Lexicon

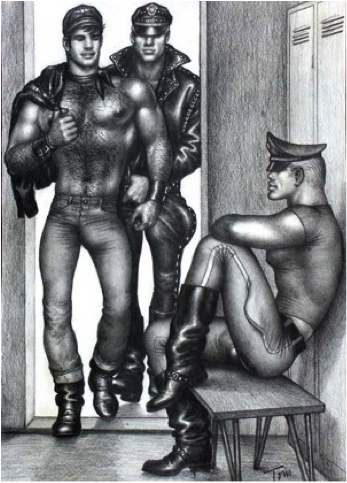

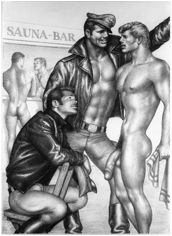

<10> Common throughout the 20th century, gay-male culture has adapted such countercultural behaviors as the Hanky Code, dressing in drag, and coopting dual-meaning lexicon. Originated by gay men in San Francisco after the Gold Rush, the Hanky Code was a color-coded system common among steam railroad engineers, miners, and cowboys in the Western U.S. Modern iterations of the Hanky Code started in New York City in the early 1970s to indicate one's sexual preference. The use of the Hanky Code mimics natural mating displays of some firefly species, whereby female [Photinus] fireflies flaunt colored patterns to attract specific mates.

<11> Mirroring traditional gender roles, the Hanky Code also announced one's acquaintance with dominant and submissive roles. Witnessed in biological systems, Selin Kesebir argues that as with the Hanky Code, language and symbols are essential to the success of any superorganismic (complex) systems. "In sum, symbolic communication is foundational to human sociality. Symbols play a crucial role in fulfilling each requirement for, a superorganismic formation: They foster coordination and cooperation by facilitating planning, information sharing, norm enforcement, and boundary marking." (Kesebir 2011)

Queer Contemporary Art and Literature<12> The contemporary art world has witnessed dramatic shifts in visual expressions of gay sexuality. In her essay "Queer Wallpaper," Jennifer Doyle revisits how "In the 1980s, the AIDS crisis added a new level of urgency to the battle against homophobia - and it is at this moment that we begin to see the word 'queer' as circulating in academic writing, and in and around contemporary art." (Doyle 2006, 391) She adds that queer work is not necessarily homoerotic in nature. In dialogue with Felix Gonzalez-Torres' Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A., 1991) much contemporary art of the time was created to encourage active-audience participation.

|

|

|

Figure 2: Felix Gonzales-Torres, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA), candies on floor, 1991 |

<13> Works by Andy Warhol and David Hockney, both openly gay artists, were more widely accepted than those by more homoerotic gay artists as Robert Mapplethorpe and Tom of Finland. Their creation of less-explicitly gay, erotic art ultimately allowed Warhol and Hockney's sexuality and queer themed work to be eschewed. Tom of Finland and Mapplethorpe were celebrated for their avant-garde approaches toward sexuality, however due to censorship codes, their work was viewable mostly in private collections.

|

Figure 3: Andy Warhol, Dirty Art: Torso & Sex Parts , silkscreen, c. 1970 |

Figure 4: Andy Warhol, Gold Marilyn Monroe, silkscreen, 1962 |

<14> Restricted by more traditional, mainstream curatorial processes, Doyle discusses the ways in which openly gay artists like Warhol are de-gayed in order to survive in the traditional art market. She tells of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles' 2002 Andy Warhol retrospective, where "The 'de-gaying' effect was reinforced by the fact that the museum had no wall text: the museum wanted to let the works 'speak for themselves.'" (Doyle 2006, 397) Taking the gayness out of Warhol's work, museums are able to present artifacts of popular culture without alienating donors and visitors. Sadly, this process negates influential elements of Warhol's identity.

<15> Gavin Butt's essay "The Inning of Andy Warhol" helps contextualize Warhol's complicated relationship with the 1950s homophobic art world, "In tracing a shift, then, from a widespread homophobic denunciation of Warhol as a sissy pre-1962 to his critical celebration as an (asexual) dandy post-1962, I will tell my story: that of the 'inning' of Andy Warhol. Moving from an Andy 'outed' as an effete gay man to one pushed back in the closet; from one kept out of the art world to one finally admitted in to the circuits of art-world sociability and critical legitimacy…" (Butt 2005, 100) Weary of homophobic responses, young Warhol decided to de-sexualize his image and create a commercial persona appreciable by all. In his essay, "Warhol Gives Good Face," Jonathan Flatley contends, that Warhol's iconizing of impersonal mass-produced commercial goods can be seen as his response to rejection as an effeminate gay man.

<16> Still, Jennifer Doyle argues that much of Warhol's work serves to celebrate gay culture. His role as a gay artist, creating critical and sexualized works, is secure. Warhol's Dirty Art series featuring Torsos and Sex Parts (1991, fig. 5) glorified homosexuality and criticized ignorance. This series further illustrates Warhol's creation of homoerotic narratives throughout his career. Blending with consumer culture, Warhol gradually reintroduced conceptual-erotic art, further developing the gay activist network.

Figure 5: Andy Warhol, Dirty Art: Torso, photo and mixed media prints, 1991

<17> Through Pop Art and culture, Warhol contextualized the contemporary art scene. Doyle discusses how "We can construct other contexts and histories for contemporary queer art, or better yet, we can look at the work of contemporary artists to see how they imagine alternative historical contexts for themselves. In part because so much of the history of gay and lesbian life is a history of exclusion and erasure, much queer art takes history (and even 'Art History') as its subject." (Doyle 2006, 399)

<18> Symbolic of the desire for many gay artists to stand out, David Hopkins discusses Mapplethorpe's homoerotic and sexualized imagery, "In publications such as 'The Black Book' [(1986, fig. 6)] he produced provocative, classicizing images of black males. Critics argued as to whether, as a white homosexual, he was objectifying his subjects or whether he was summoning up the spectre of a mythologized black potency to unsettle his predominantly white gallery-going audience" (fig. 7). (Hopkins 2000, 197) In dialogue with such criticisms, Mapplethorpe created such contentious works, aiming to iconize and bring the appeal of the black man into the direct focus of society and the art establishment. (Mitchell 2001) However, so far beyond notions of 'whiteness' and 'blackness,' "Mapplethorpe's work…represents 'erotic' photography which 'takes the spectator outside its frame … as if the image launched desire beyond what it permits us to see: not only toward 'the rest' of the nakedness, not only towards a fantasy of a praxis, but toward the absolute excellence of a being, body and soul together." (Yingling 1990, 9) Much of his appeal is the way in which such works stay with their viewers. Mapplethorpe's work is anti-ephemeral; it's timeless.

|

Figure 6: Robert Mapplethorpe, The Black Book, photo of cover art, 1986 |

Figure 7: Robert Mapplethorpe, Ajitto, a series of 2 gelatin silver prints, 1981 |

<19> Sometimes publicly funded, Mapplethorpe's work successfully denigrated many American conservatives. Hopkins explains how "In 1990 a touring retrospective of Robert Mapplethorpe's sexually explicit photographs […] succeeded in provoking ringing accusations of obscenity from American conservatives. Mapplethorpe had died of AIDS in 1989 and the entire conjunction of circumstances led to a right-wing campaign against the imputed moral laxity of the arts, one outcome being a debate concerning the distribution of government funding by the US National Endowment for the Arts. It is clear, then, that the social determinants of late 1980s art were manifold." (Hopkins 2000, 227)

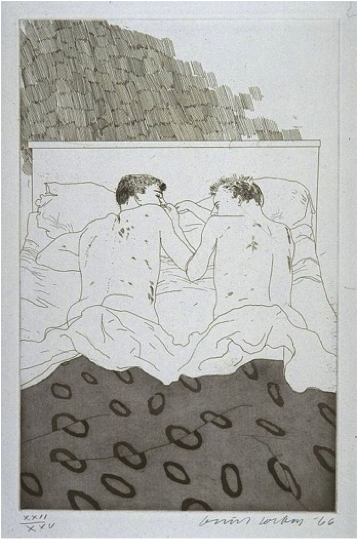

<20> Across the Atlantic Ocean, David Hockney's work was widely criticized in his home country of England. While very much less sexualized - than Mapplethorpe and Tom of Finland's work - much of his work was still deemed immoral and illegal. Hockney's etchings and paintings provided a gaze upon the more ordinary and intimate aspects of what homosexual life may look like (fig. 8-10). Amongst other elegant imagery, Hockney's representation of the queer lifestyle as warm, loving and honest provided audiences with a new way to view homosexual intimacy, which better coincided with their hetero-normative expressions of sexuality.

|

Figure 8: David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), acrylic on canvas, 1971 |

Figure 9: David Hockney, Peter Getting Out of Nick's Pool, oil on canvas, 1967 |

Figure 10: David Hockney, Two Boys Aged 23 or 24, etching with aquatint, 1966

<21> Hockney broadened the ways in which media discovered the homosexual community. Society also dismissed the possibility for intimacy and sensual context within Tom of Finland and Mapplethorpe's work. This misunderstanding strengthened shallow perceptions of homoerotic works; presuming that because one sees genitalia or sex, that it is therefore devoid of sensual and intimate context. This presumption lessened the value of such work, but fueled their political/activist effect, which was critical of mainstream social dynamics; "Interestingly, Mapplethorpe's work arises from a homosexual site at precisely that historical moment (the late 70s and 80s in New York) when gay male culture rejected the discourse of sexual difference and its parody of male/female roles as the paradigm most appropriate to it." (Yingling 1990, 10)

<22> Beyond its discourse with homosexuality and eroticism, Mapplethorpe's work brings into discussion the elevation of the black man to a sculptural and fantastical level; "The very notion of bodies with a 'polish' almost literally objectifies them, making them ebony sculptures in a white fantasy; and far from subverting white clichés, the discourse of reflectivity … is whole contained within racist paradigms. The natural 'potency' of the black man's body disarms, makes impotent, any response other than awe: it naturalizes the discourse that situates it as an object for the gaze." (Yingling 1990, 11)

|

Figure 12: Robert Mapplethorpe, Green Bag, mixed media, 1971 |

Figure 13: Robert Mapplethorpe, Ken and Tyler, black and white photography, 1985 |

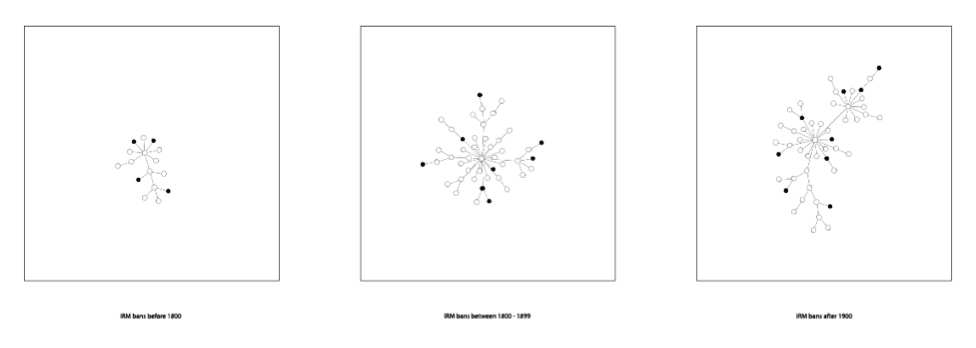

<23> Mapplethorpe's elevated images of the black man up to a position of power, within a white world, left conservatives feeling uneasy. Coupled with the 'natural potency of the black man's body,' concerns over social prowess as well as those of a sexual nature challenged generational assumptions of racial power structures. The erotic power and symbology associated with Mapplethorpe's work, resonates today, as well. Through their raw strength, works like "Ken and Tyler" (1985, fig. 12) and "Ajitto" (1980, fig. 13) still speak to the sexual and evocative nature associated with the physical form of man objectified by the audiences gaze.

<24> Paralleling Mapplethorpe and Hockney, Tom of Finland's work was clearly more transparent. In Dirty Pictures, Micha Ramakers speaks of the unwavering thematic strength visible throughout Tom of Finland's campaign of work. "Tom's themes were hardly subject to fundamental change. Neither the liberation of legislation governing pornography nor artistic recognition had a decisive influence on his work's basic premise. The relation between sexual pleasure and power remained its central theme throughout." (Rimakers 2000, xi) Like Mapplethorpe, Tom of Finland's work encouraged dialogue of homoerotic relations and social acceptance of homosexuality. Given censorship codes and sexualized visual content, Tom of Finland's work, too, was relegated to the periphery of society and rejected by the global art world. As this was the case, his work empowered young homosexuals to find common ground, ultimately creating unified 'networks' of gay activists, and "For many being gay became not a problem, but something to be proud of." Tom of Finland's ideal images of a gay world played a significant role in the formation of many young gay male identities. "His almost obsessive adherence to one style and theme-and over time those two elements became inextricably connected-formed a key element in Tom's creation of the most effective propaganda for a gay utopia produced to date." (Rimakers 2000, xi)

<25> Thomas Yingling discusses in his essay, "How the Eye is Caste: Robert Mapplethorpe and the Limits of Controversy," how Tom of Finland's illustrations projected a greater level of masculinity, traditionally representational of the heterosexual male, onto the image of the gay male form, with no essence of femininity. "The new national lesbian and gay quarterly, OUT/LOOK, recently ran a retrospective of the work of Tom O'Finland, a Los Angeles illustrator who, in the words of one admirer, 'draws good horny porn' that, in the words of one detractor, presents 'over-muscled, thick-necked, jut-jawed, small-brained idols of male domination.'" (Yingling 1990, 11) Tom of Finland fetishized, bruiting and homoerotic characters, pulled from his time, and re-contextualizing Navy men, construction workers and leather daddies as focal characters; as queer but never sissy.

|

Figure 14: Tom of Finland, Untitled, graphite on paper, 1965 |

Figure 15: Tom of Finland, Youthful Innocence, graphite on paper, 1969 |

<26> For generations, gay contemporary artists have wrestled with the dismissal of gay- and homosexual-themed art. Attempting to counter homophobia, controversial gay artists sought acceptance of homosexual relations. Gay artists, like those discussed, warred against homophobic censorship and narrow perceptions that delineated homosexual and heterosexual visual arts. Ultimately, gay artists turned their focus toward critical examinations of contemporary social constructs, seeking to showcase the male (and female) form, while considering the sensual eroticism associated with gay sexuality and love. Hidden in such works as Hockney's Two Boys Aged 23 or 24, (fig. 11), are messages of lust and intimacy, unwilling to be acknowledged by conservatives and the elitist fine art institution. Measures taken by renowned gay artists of the 1960s-70s have paved the way for today's contemporary gay artists.

Section 3: Digital Media Art Influences

<27> This section surveys interactive and new media artists that are also outspoken activists and/or educators. They have each influenced the conceptual, artistic and technological creation of Nature & Spirit and assist in supporting discussions of complexity, emergence, cellular automata, and appropriation of data for artistic purposes.

R. Luke DuBois: composer, artist and performer

<28> R. Luke DuBois creates visually and sonically evocative projects focusing on questions of cultural and personal moments. Pulling from 'visual language and cultural vocabulary,' DuBois' work speaks to disparities across socio-cultural and economic class divides, within Western society. Co-author of Jitter, a visual development tool for the visual programming software Max, allows artists and composers the ability to manipulate visual data in real-time matrixes (or grids), visually similar to cellular automata structures.

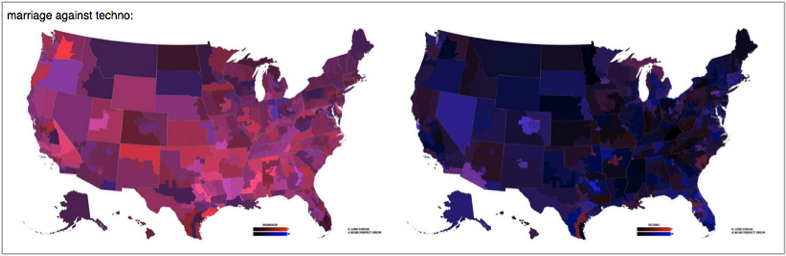

Figures 16 and 17: R. Luke DuBois, A More Perfect Union, online visual art, 2008-10

<29> DuBois' work A More Perfect Union (2008-10) is an online series that focuses on the visual representation of online dating data over the U.S. Census. This work envisions census data in unorthodox formats, determined not by economic classes but by 'love.' Conscious of cultural differences between social preferences and identifiers (e.g. gender roles, sexual preferences, marital statuses, cultural beliefs, etc.) DuBois explores the broad vocabulary of Western romance. He states that:

"This lexicon of American romance, as it were, consists of more than 200,000 unique words, and gives an imperfect, but extremely interesting, perspective on how Americans describe themselves in a forum where the objective is love." (DuBois 2010)

<30> DuBois' work is most inspiring for its culturally critical responses toward, and his ability to bring attention to, social and political concerns across Western culture. Creating entirely new and sometimes inseparable bodies of work, Hindsight is Always 20/20 (2008) is a prime example of his influential talent. Developed as a live, audio composition, this piece plays the American National Anthem over four years, allowing its sonic landscape to represent a traditional Islamic call to prayer.

Golan Levin: new media artist, composer, performer and engineer

<31> Considering the grid nature of Jitter matrixes and cellular automata, Golan Levin's Self-Adherence (2010) speaks directly to principles of networks and communities discussed throughout this paper. In Self-Adherence, Levin has created a series of generative visual forms representative of biologically symbiotic relationships. Taking into account each neighbor, a cell is "developed from a feedback process in which thousands of small elements are mutually attracted to their nearest neighbors." (Levin 2010)

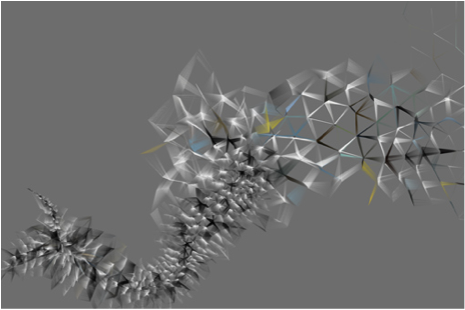

Figure 18: Golan Levin, Self-Adherence (for Written Images) 2010

<32> Much of Levin's work addresses discussions of connectivity and impact, through the prescribed language of interactivity. Mirroring pheromone communication between insects, and the universal ways that users interpret icon-based codes and lexicon, Levin calls upon the 'nonverbal' communication behaviors that drive complex digital systems.

Tmema

<33> Creating evocative bodies of work centered on connectivity and language, Levin and his collaborators bridge the space between humans and computer. Creation of visual explorations like Footfalls (2006) helps to further iterate the communicative nature found within complex systems and cellular automata.

Figure 19: Tmema [Golan Levin & Zachary Lieberman], Footfalls, 2006

<34> Footfalls (2006) - one of Tmema's projects between Levin and artistic collaborator Zachary Lieberman - is an interactive installation designed specifically with audience interaction in mind. Developed as a response to the relationships between humans and computer systems, Footfalls explores the same symbiotic connection found between interactors in insect colonies and activist networked communities. Symbolic of activist efforts, the premise of the 'butterfly effect,' and physical strength drive Footfalls' interaction, as the stronger a user stomps, the more rapidly and frequently the modules fall and gather in mass.

Casey Reas: artist, educator, programmer and engineer

<35> Casey Reas, co-author of Processing (.org), an open source visual programming language and development software, creates visual and emergent-networked art, with strong foundations in conceptual art practices. As a visual designer's tool, Processing is a visual playground that serves as an intermediary between human users and computer graphical interfaces. Reas' work is essential to hybridized discussions in Nature & Spirit and will be explored more in section 5.

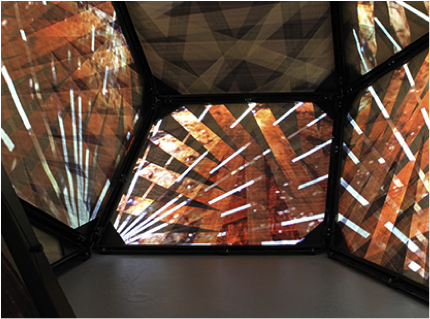

<36> Textile Room (2013) is a recent collaborative project that accentuates the physical and theoretical lines between 'hard and soft, textile and tectonic, intimate and public' and serves to represent the ability for heavy architecture to take on lighter, freer, and more whimsical forms. Accentuating Reas' ability to create versatile installation spaces, he created a video collage of Los Angeles using appropriated motion picture footage, projected on softer carbon fiber weavings. Textile Room's weavings and steel architecture blur the lines between its rigid form and the fluidity of its function, taking on the metropolitan infrastructure of its home.

Figures 20 and 21: Casey Reas and collaborators, Textile Room, 2013. Image attribution: Monica Nouwens

<37> Network A, a.k.a. Process 4 (Installation 2) is a visual project developed in Processing that regenerates drawings though a generative process; creating new and evolving networked relationships. Symbolic of biologically networked systems, Network A explores notions of connected structures within seemingly unconnected patterns.

Figures 22 and 23: Casey Reas, Network A, a.k.a. Process 4 (Installation 2), 2009

<38> The bodies of works discussed here represent explorations of complex systems, and in some instances, biomimetic creative practices. DuBois' visual and audio works create acute commentary about societal constructs, whilst bringing complex data visualizations into the daily lives of viewers. Levin's Self-Adherence was created using a series of virtual simulations of cellular automata also visible in complex biological systems. Reas' Textile Room and Tmema's Footfalls create exploratory environments where participants actively encounter digital media techniques within physical spaces, participating in the creation of complex systems. Nature & Spirit seeks to create an evocative setting for participants to feel and observe cultural discussions of sexual identity and biological politics, through a technologically driven experience.

Section 4: Creative Media

<39> Creative media are everywhere, everyday. This Chapter explores how the use of creative media, specifically imaginary media and speculative realism and fiction can generate social change. Similarly, artists and authors use these approaches to raise awareness around issues of gender and sexual equality, through digital art and literary explorations.

Imaginary Media and Speculative Realism

<40> Originally published in 1818 (London), Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus represents one of the first published literary references of imaginary media and speculative fiction (media that are not yet possible at the time of envisioning). Inspired by personal observations traveling Europe, Shelley's character, Dr. Victor Frankenstein creates his first successful reanimated being. Through the practice of galvanism Frankenstein's Monster is re-born (Shelley 1818).

<41> Sadly experimentations in galvanism became more commonplace in modern culture(s), leading to abusive practices of electrotherapy and electroshock therapies, which I will discuss in the next section. Imperative to discussions of Shelley's work and imaginary media are notions of the corporeal form.

<42> Rooted in post-Kantian explanations of modern philosophy, speculative realism (and fiction) explores the 'opposite to dominant forms,' and lends perfectly to discussions of sub and counter-culturalism. Originating at a 2007 Goldsmiths College, University of London conference, speculative realism explores metaphysical realism: discussions of human ontology separate from physical and visible factors and artifacts, participants sought to question Kant's notion of 'human finitude,' the philosophical argument that humans are limited to what they can and cannot do. (Brassier et al. 2007) I believe that ideas discussed here can be made more tangible through the 'outing' of Marvel's Iceman.

Marvel Comic's: The All-New Iceman

<43> LGBTQ characters began appearing more commonly in the 1990s across television and film. The science-fiction show Babylon 5 introduced Susan Ivanova, its first bisexual character; Xena: Warrior Princess, a fantasy television series created great fan speculation around Xena and Gabrielle's relationship, ultimately catapulting Xena as a lesbian icon; and beginning in 2006, the BBC's science-fiction series Torchwood hosted bisexual and homosexual male characters and love stories. The appearance of lead LGBTQ characters has helped bridge gaps between actors and audiences.

<44> The 'outing' of Iceman also stands to gain much fan appreciation, as the X-Men brand has always drawn clear correlations between the culture-at-large and sub- and countercultural communities. Iceman may be the first gay mainstream Marvel character to be 'outed,' but as with all X-Men (and women), he is not the first to draw attention to disparities in gender, social and sexual equality across Western popular culture. (Abad-Santos 2015) As a brand, the X-Men might be able to speak to all viewers.

<45> Moving forward a long way from the X-Men and Iceman of the 1960s, I hope that the current day franchise recognizes the importance of its influences, and social acceptability of diversity amongst its protagonists and antagonists.

Figures 24: Marvel Comic, "All-New X-Men #40," illustrated comic, 2015

<46> LGBTQ themes are apparent throughout speculative fiction incorporating a diversity of alternative and queer-centric themes into science fiction, fantasy, horror, futurist, romance, etc. Wayne R. Dynes (et al) argues that in the later half of the 1960s varying genres within speculative fiction began to expose the changes prompted by the civil rights movement and the emergence evolving acceptance countercultural groups, slowly transforming them into subcultural communities. Once critical commentary of the 1960s and 70s subsided, bisexuality, homosexuality and transgendered individuals and communities began gaining wider acceptance as heroes in speculative and science fiction. (Dynes et al. 1990)

<47> In this vein, a new comic novel series, Providence, by Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows was inspired by H.P. Lovecraft's literary scholarship, however delivered through a new lens. In a recent interview, the creator's speak to Lovecraft's notorious homophobia and anti-Semitism seen in both his personal and literary life. Moore argues that as others [artists and authors] have not spoken-out more critically about Lovecraft's narrow views, it's about time that someone turns his own practice against him. Pushing the evolving speculative fiction movement further, Moore and Burrows have created a gay, Jewish protagonist to help tell their stories. (Shannon 2015) This adds significant credence to Dynes' (et al) assertions that the speculative and science fiction genres continue to grow as playgrounds for the propagation of diversity and the support of outcasts, underdogs and the 'atypical' members of society.

Section 5: Nature & Spirit: A Digital Lens of Gay-Male Culture

|

|

|

Figures 25 and 26: Nature & Spirit long shot, mixed-media series, 2015

<48> Nature & Spirit creatively interweaves the principles of biomimicry, with discussions of sexual and biological politics, and the empowerment of sub and countercultural communities. Analogizing biological swarm networks, Nature & Spirit explores the culture-at-larges' influences on gay-male communities through discussions of sexual identity and equality, dominance and submission, social roles, and notions of modern families. Nature & Spirit investigates the visual dynamics of insect and collective swarm patterns through the video projection; remixing and contextualization of swarm simulations and the application of gay and 1960s interracial societal data. In part this series explores natural interactions between large and small-scaled bodies of work, which encourage the recognition of gay artistic and activist efforts through the creation dialogue and promotion of community participation. And, through its technical and physical composition and visual content, Nature & Spirit speaks directly to my feelings and recollections of my childhood, my reconciliation with my own homosexuality, and how I hope the future of the 'modern family' may take shape.

Therapeutic Nightmare

<49> Central to this discussion, Therapeutic Nightmare sets the stage for broader questions of how modern families embrace queerness. This piece reflects my upbringing and the personal exploration of my 'coming out' process. As my concept of the modern family is visualized upon individual surfaces of the dining table, it culls notions of 'traditional' families mixed with aspects of my gay-male identity, reimagining an idealistic representation of a modern family.

<50> This exploration serves to investigate electroshock therapies used to cure gayness. For generations reparative therapies have used many such dreadful techniques in the hopes of correcting deviant behavior(s). Drawing attention to the rigidity of their form and the evocative nature of their function, these electric chairs draw visitors inward to interact with this body of work. As participants sit at the table their presence triggers Therapeutic Nightmare's projected visual content, which explores the interplay of sexual identity, gender roles through a mix of contemporary (1950-80s) and modern (1990s-present) popular culture references through in text, coded icons and lexical icons. The table matches the aesthetic of the electric chairs, completing the physical structure of Therapeutic Nightmare.

|

|

|

Figures 27 - 29: Therapeutic Nightmare close-up shots, mixed-media series, 2015

<51> Motivated by Andy Warhol's Death and Disaster series, this investigation surveys electro-shock therapies used to 'cure the gay away.' As a gay man I often felt I was different than others, and while part of a loving family, something separated me from most everyone else. As a whole, the community of chairs represents the lack of comfort I felt in my own skin, and as a youth how I always felt on edge. The red chair stands out from the rest, and is placed at the head of the table, to call attention to such discomfort.

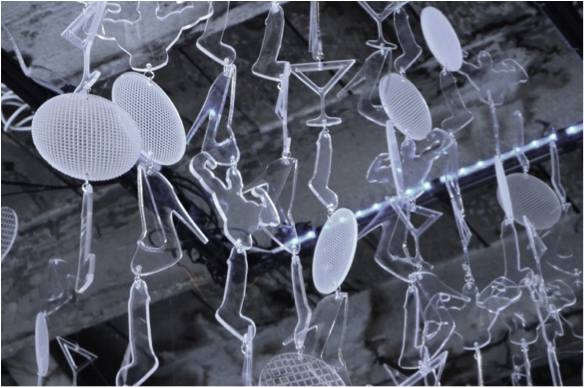

DragNet

<52> Suspended above, DragNet provides a dual-focal point that balances the tables visual content, serving the purpose of a formal chandelier, in a traditional dining room setting, while making a statement regarding the inclusion of homosexuality in family dinner conversation through its construction from pieces symbolic of more flamboyant gay culture. Dually this allows DragNet to be a part of Therapeutic Nightmare while also providing another point for discussion.

|

|

|

Figure 30 and 31: DragNet, laser cut and etched sculpture, 2015

<53> Borrowing inspiration from the movement and texture of bees (hives) and fireflies (bioluminescent mating processes), DragNet is a lit and suspended installation that recognizes how gay-male communities are often represented across popular culture. DragNet presents varying iconic representations of gay-male culture - often the first impression for 'outsiders' - seen witnessed throughout drag (cross dressing) communities. From afar, elements of DragNet blend together forming a chandelier, which does not appear out of place or confrontational within a dining room how set. However, upon closer inspection, visitors can see that it consists of five different custom designed icons, cut and etched out of clear acrylic, which reflect different aspects of gay culture.

<54> Exploring notions of biomimicry, DragNet investigates a symbolic approach to complex biological systems through an investigation of natural swarm patterns atop modern iconic representations of gay-male culture. Like natural swarms, gay-male communities have united - often adapting to their surroundings by mimicking those that objectify them - standing strong in the face of adversity. DragNet's movements represent activist behaviors. Moving as one defensive unit - forming a networked community - DragNet empowers and gains energy from its overall networked system.

DataLith [Process 1 and 2]

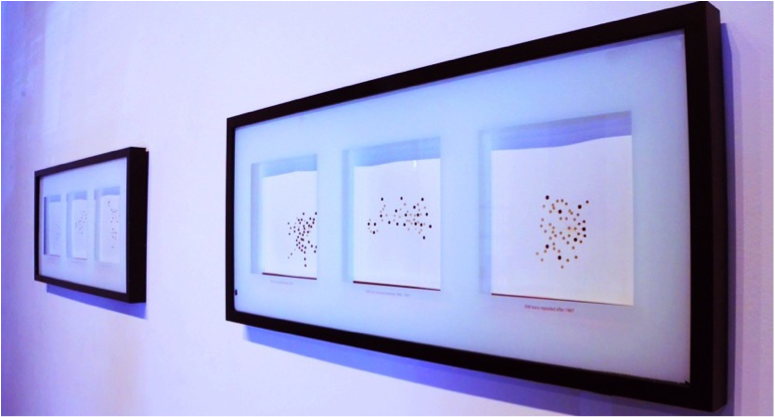

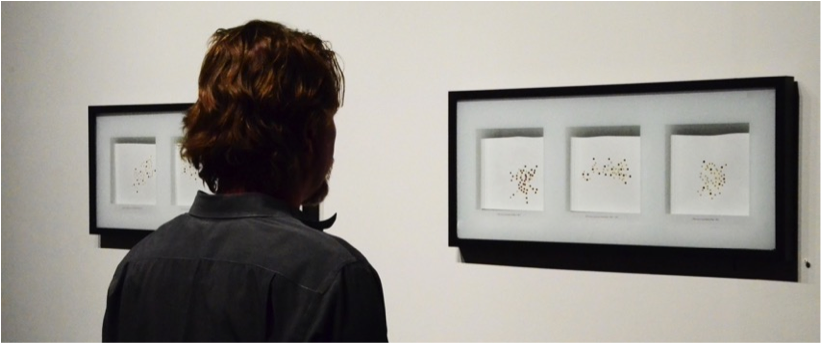

Figure 32: DataLith [Process 1], data visualization prints on display, 2015

<55> DataLith [Process 1] is a series of generative, data-driven visual explorations including timeline and demographic trend correlations between U.S. state gay marriage bans and repeals, and 1960s Civil Rights movement interracial marriage bans and repeals. DataLith [Process 2] explores the astrological birth chart data for the Stonewall Uprising (1969) and the passing of California's Proposition 8 (2004). Laser etching data content into woven paper offers a softer and more eloquent function juxtaposed against DataLith's harder form. Visualizing the data also utilized in Therapeutic Nightmare and DragNet, DataLith is coded in Processing and Netlogo and explores relationships developed within human and natural complex biological systems.

<56> DataLith is personal as it surveys modern historical bans and repeals that affect me as a Californian, an American and as a married gay man. Data regarding gay marriage bans and repeals are presented alongside similar data for interracial marriages, drawing a correlation between the Civil Right's movement in the 1960s and the push for gay equality today.

Figure 33: DataLith [Process 1], data visualization prints on display, 2015

DataLith [Process 1]

<57> Coded in Netlogo, historic U.S. marriage data was fed into a live, generative algorithm and recorded in real-time. Stills of these recordings were inverted and laser cut into woven paper, accompanied by descriptions that are laser etched into each frosted glass surface. Data regarding U.S. Gay Marriage bans and repeals are presented alongside similar data for U.S. Interracial Marriage bans and repeals, drawing a correlation between the 1960's Civil Right's movement and the current push for gay equality.

Figure 34: DataLith [Process 1]: Gay Marriage bans, data visualization screen shots, 2015

Figure 35: DataLith [Process 1]: Interracial Marriage bans, data visualization screen shots, 2015

DataLith [Process 2]

<58> As significant as codes, interpreting astrological data is a way of combining spatial and temporal data necessary to calculate the exact degree of all signs as they rise and set. Coded in Processing, astrological birth chart data about the Stonewall Uprising and California's Proposition 8 were fed into a live, generative sketch and recorded in real-time. Stills of these recordings were inverted using Photoshop and laser cut into woven paper using Illustrator; degree, minute, second and axes indicators have been laser etched into each frosted glass surface.

Figure 36: DataLith [Process 2]: The Stonewall Uprising, data visualization prints on display, 2015

Figure 47: DataLith [Process 2], screen capture of data modeled over x, y & z axes, 2015

<59> The use of emergent digital media tools has adjusted the lenses that artists, makers and scholars use to creatively explore the world. Thankfully the use of such tools and practices has helped strengthen the ways in which activist groups position themselves, and the ways in which they gain support and greater acceptance throughout the culture-at-large. My hope is that the continual exploration of new and open source digital media tools will continue to support the successful evolution of countercultural communities toward becoming sub-cultural communities, and ultimately better accepted across society, eliminating the prevalence of the culture-at-large.

<60> Nature & Spirit takes a critical look at the use of emergent digital media techniques utilized across popular activist culture, promoting correlations between complex biological and human social systems. Given human desires for autonomy and immunity, human systems are incrementally more complex (than natural biological systems) and have therefore gained a greater need for technological intervention and mediation.

<61> Exploring biomimetic practices, Nature & Spirit creates a conceptual, interactive and culturally participatory survey of sexual identity and biological politics (through the Western world), and promotes gay-male activist use of digital media resources. Nature & Spirit's exploratory approach to the use of emergent digital media and making practices - through open source visual language environments and digital media tools - promotes community involvement. Nature & Spirit references for the natural spirit within all beings regardless of personal differences, and has been a greatly personal exploration.

Notes

1. Alex Abad-Santos. "What a gay Iceman means for Marvel," Vox magazine, April 22, 2015, http://www.vox.com/.

2. Ray Brassier, Iain Hamilton Grant, Graham Harman, and Quentin Meillassoux, "Speculative Realism," in Collapse III: Unknown Deleuze, London: Urbanomic (2007)

3. Gavin Butt, Between You and Me: Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948-1963, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 100.

4. Michael Chanan, "Video, Activism and the Art of Small Media," Transnational Cinemas 2, no. 2 (2011): 217-226.

5. Jennifer Doyle, "Queer Wallpaper." The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology: A Critical Anthology, ed. Donald Preziosi, (England: Oxford University Press, 2006), 391-400.

6. Luke R. DuBois, A More Perfect Union, accessed April 22, 2015, http://www.bitforms.com/.

7. Wayne R. Dynes, Warren Johansson, William A. Percy & Stephen Donaldson, Encyclopedia of Homosexuality (Connecticut: Garland Publishing Inc., 1990), 752.

8. Roberto Esposito, "Community, Immunity, Biopolitics," Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, Volume 18, no. 3 (2013): 83-90.

9. Peter Gidal, Andy Warhol Blow Job, (Cambridge, Mass: Afterall Books, Distribution by The MIT Press, 2008) 132.

10. Fox D. Harrell, Phantasmal Media: An Approach to Imagination, Computation, and Expression, (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2013).

11. David Hopkins, "Postmodernism: Theory and Practice in the 1980s," in After Modern Art, 1945-2000. (England: Oxford University Press, 2000), 197-231.

12. Selin Kesebir, "The Superorganism Account of Human Sociality: How and When Human Groups Are Like Beehives," Review Personality and Social Psychology, Volume 16, no .3 (2011): 233-261.

13. Golan Levin, Self-Adherence, accessed April 22, 2015, http://www.flong.com.

14. Hannah Means Shannon, "Alan Moore Writes a Gay, Jewish Protagonist for Providence to Address Lovecraft's Prejudices," April 23, 2015, http://www.bleedingcool.com.

15. W.J.T Mitchell, "Offending Images," in Unsettling "Sensation": Arts-Policy Lessons from the Brooklyn Museum of Art Controversy, ed. Lawrence Rothfield. (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 2001), 115-133.

16. Jussi Parikka, What Is Media Archeology?, (Great Britain: Polity, 2012).

17. Jussi Parikka, Insect Media: An Archaeology of Animals and Technology, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 29.

18. Micha Ramakers, Dirty Pictures: Tom of Finland, Masculinity, and Homosexuality, 1st ed. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000), xi.

19. Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, 1st ed. (London, 1818).

20. Thomas Yingling, "How the Eye Is Caste: Robert Mapplethorpe and the Limits of Controversy." Discourse 12, no. 2 (1990): 3-28.

Return to Top»