Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 1

Return to Contents»

Making the Posters Dance: Victor Moscoso's Four-Dimensional Posters and Adventures in Exhibition Concept, Design, and Archiving* / Scott B. Montgomery

<1> Generally, posters do not move, let alone dance, wave, wink, or fly. They tend to stay still, affixed to walls. In keeping with the advertising mandate originally inherent in the medium, clarity in delivering a message is frequently a guiding principle in poster design. Artistry is employed in the service of communicating the idea, whether political, social, or commercial. But art's role has tended to be subservient - to attract the viewer's eye toward the advertising message. Transcending this, the poster reached its first artistic apotheosis in the late 19th/early 20th century work of Art Nouveau masters such as Alphonse Muccha. Taking a cue from Art Nouveau posters, 1960s psychedelic poster artists brought stunning visual artistry to the forefront - ignoring the advertising mandate traditionally imposed upon the medium. While vibrant artistic pockets existed elsewhere, the cultural nexus of the psychedelic poster movement was San Francisco. Here a countercultural hothouse environment spawned a distinct aesthetic vision. Reproducible and inexpensive, posters were the ideal visual format for the so-called "hippie" counterculture's self-expression. Psychedelic posters are the high art of the counterculture.

<2> This fecund cultural environment nurtured a tremendous sense of artistic experimentation, the fruits of which include some truly audacious artistic challenges to any perceived limitation of the poster's possibilities. The art of the psychedelic poster is in opposition to the traditional mandate of immediate, clear delivery of the advertising message. Instead, psychedelic posters request that you explore their visual splendor, their optic play, their art. It is more about the ride than the message. This is, of course, perfectly in accord with the general psychedelic ethos of exploring new possibilities and impossibilities by transcending or side-stepping expectations, norms, and perceived realities, as expressed in slogans such as "Turn on, tune in, drop out" and "Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream."[i] Psychedelic posters invite you to slow down, accept the ride, and find meaning in your own way and at your own pace. Take time to look and enjoy the visual trip is the psychedelic poster's siren call.

<3> Spanning roughly 1965-1971, the San Francisco area psychedelic poster movement enjoyed its real apex in 1967-68. Part art movement and part cultural phenomenon, psychedelic posters were the visual nexus for the expression of countercultural identity, ideals, and recreations. Among the numerous poster artists, eight emerge as the most significant in terms of quality, quantity, and influence. These are among the greatest pioneers of the psychedelic aesthetic - Stanley Mouse, Wes Wilson, Rick Griffin, Alton Kelley, Bonnie MacLean, Lee Conklin, David Singer, and, of course, Victor Moscoso. Their elevated artistry and experimental conceptions fashioned some of the most iconic imagery of the era. Formulating a suitably varied psychedelic style, these poster artists fused diverse elements of dynamic line, bold color, surreal and shape-shifting imagery, experimentation with printing techniques, and a general sense of embracing the ineffable, the indefinable, and the unpredictable. All psychedelic artists invite a sense of visual play, but along with Griffin and Conklin, Moscoso excels at forcing us to work hard at this play. An investment of time is essential to "get it," though the reward is great. We don't necessarily slow down because we want to, but rather because we must. The posters draw us in, rewarding protracted gazing by revealing their secrets slowly. Viewing becomes more about looking than necessarily understanding. Psychedelic and countercultural ideals are artistically expressed in the visual exploration of what one Acid Test flier heralded "expect the unexpectable."[ii]

<4> One of the most unexpectable artistic manifestations of the poster movement was the evocation of movement on posters - the play of time. This was most dramatically achieved by Victor Moscoso in the eight four-dimensional (4D) posters that he produced during 1967-68. These are stationary images that perform the passage of time when viewed under special lighting conditions. I call them 4D posters because they play within the realm of time, as their designs only unfold over time, becoming almost cinematic. Through strategic use of off-set lithographic printing and the development of a special light box, Moscoso was able to fashion "moving" posters that transcend their traditional poster-ness and "enter the realm of poetry," as the artist notes. Moscoso's 4D posters are an innovative fusion of ideas related to kinetic art, light art, cinema, and graphic design. He was not making advertising posters, but rather making art in the poster medium. Novel in concept and execution, these posters are among the most daring experiments of the psychedelic poster movement in the San Francisco area. Appearing during the zenith of 1967-68, these posters should be seen as part of these artists' endeavor to challenge the boundaries of art. Moscoso consciously challenged himself to explore new artistic frontiers, pushing the poster beyond its traditional boundaries. The most formally and theoretically-trained of all the movement's artists, Moscoso had studied with color-theorist Joseph Albers. Putting his art-school background to good use, particularly in his groundbreaking psychedelic color experiments, he wanted to break the poster's so-called "five-second rule" of advertising, wishing to slow one down and take time to look. Now, Moscoso sought to make one look at time. In doing so, he extended the psychedelic poster's conceptual novelty to its farthest reaches - transcending its very poster-ness. And why not? If three-dimensional people were aspiring toward the fifth dimension, why couldn't two-dimensional posters reach for the fourth dimension?

<5> Fluid, stretched time has always been a key factor in psychedelic art and experience. Moscoso took this axiom in the most novel direction with his 4D posters, images that do not move but appear to with changing lights (or blinking eyes). In doing so, the posters transcend their existential planarity, their very "posterness." They become images about time and motion themselves. There is a dimensional slippage here, as the spatial third dimension is bypassed on the way to the temporal fourth. In much the same way that he intentionally inverted traditional rules of color harmony in his exploration of the possibilities of intense color juxtaposition, Moscoso stormed the gates of time by changing the rules. This pioneering extension of the poster's possibility invites an almost synesthetic transcendence of media, the senses, and perhaps even sense. As Moscoso so beautifully articulates it, "You get the dimension of time....and it enters the realm of poetry and music."[iii]

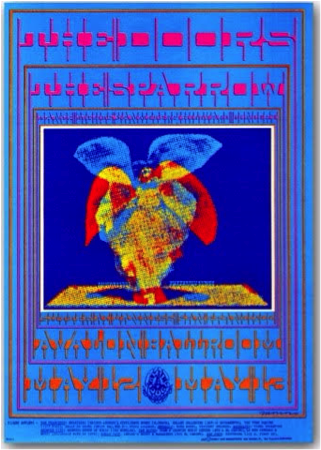

<6> While designing a poster for The Family Dog's concerts by The Doors and The Sparrow (shortly to evolve into Steppenwolf) at San Francisco's Avalon Ballroom on May 12-13, 1967 Moscoso came across a photograph that would felicitously inspire his exploration of the fourth dimension in poster art. [iv]

FIGURE 1 - Victor Moscoso. The Doors, The Sparrow. May 12-13, 1967. Avalon Ballroom, San Francisco (FD-61). © Rhino Entertainment Company. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

<7> "It comes from Edison. I was looking through a book on silent films. I saw a kinetoscope with a 35mm film loop inside - the loop was shot by Edison and it was a lady named Annabelle dancing with wings."[v] This was doubtless a screen-still from W.K.L Dickson, William Heise, and Thomas Edison's 1894 film of Annabelle Whitford's terpischorian flutters, known as Annabelle's Butterfly Dance.[vi] The 4D aspect "was originally a mistake. I stumbled across it the way Columbus stumbled on America." [vii] In keeping with the experimental ethos of the time, Moscoso printed the image off-register to see how it would look. "I got one frame with the wings up, and I wanted to echo the movement by printing the colors off-register. A friend of mine - Howard Hesseman - had a hallway covered with dance-concert posters, lit with Christmas tree lights. The red, blue and green were strong. The yellow was too weak. And he said 'Victor, you know that poster you did last week, with the lady with wings....well, she flies!' And I knew how his hall was arranged with the lights, so I knew exactly what he was talking about. The red canceled the blue and the blue canceled the red."[viii] Though interested in exploring the suggestion of movement, Moscoso had no idea that the right lighting would translate a suggestion of wings moving into a full-fledged perception of them flapping in time - the fourth dimension [FILM 1]. The alternating colors cancel one another, making the readily visible part of the poster shift as the lights change, thereby creating actual movement within the perception of the image. Simple, but revolutionary, it was a psychedelic breakthrough for the poster. It is suitably serendipitous that the image source for Moscoso's first filmic poster was an early film produced by another visionary maker of moving images. Like a screening of Edison's film framed by pulsating lettering, the poster lets Annabelle fly to an altogether different medium. Fluttering from film to film-still to filmic un-still poster, Annabelle flutters across moving pictures and moving posters alike.

<8> Though initially an accident, the idea was quickly developed by Moscoso who explored and perfected the possibilities of motion within a two-dimensional poster. Once Hesseman alerted him to Annabelle's aerial abilities, Moscoso began to explore the idea. Starting tentatively, his first conscious 4D poster advertises the Youngbloods at the Avalon Ballroom on June 15-18, 1967.

FIGURE 2 - Victor Moscoso. Youngbloods, Siegal Schwall Band. June 15-18, 1967. Avalon Ballroom, San Francisco (FD-66). © Rhino Entertainment Company. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

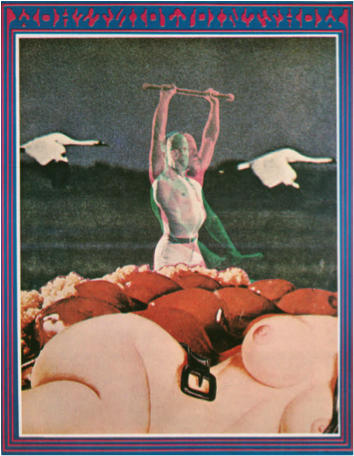

<9> Moscoso is still experimenting and the design is simple. A somnolent lady leans up to observe the flexing of an ominously-looming muscle man [ FILM 2]. With no yellow register in her head, the fluidity of its motion is somewhat reduced, as only the red and blue parts appear to change somewhat abruptly. Moscoso's third 4D design was his poster for the July 1967 Joint Show at the Moore Gallery in San Francisco (printed June 30, 1967).

FIGURE 3 - Victor Moscoso. Joint Show. July 1967. Moore Gallery, San Francisco (NR-25). © Victor Moscoso. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

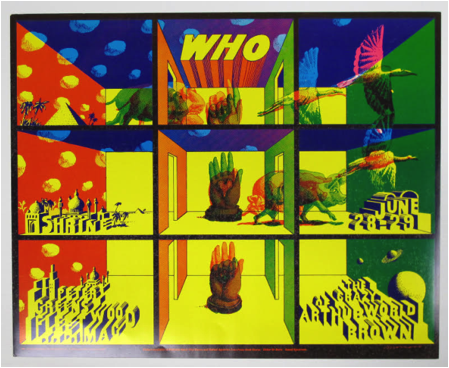

<10> Here, he tried a two-color variation of pink and green, perhaps to facilitate its use with 3D movie glasses [ FILM 3]. This too is a relatively tame design and the sense of motion is only partly successful. A year later, Moscoso would reprise the pink-green two-tone once more in the playful romp that announces the Who at the Shrine Auditorium, Los Angeles on June 28-29, 1968.

FIGURE 4 - Victor Moscoso. The Who, Peter Green's Fleetwood Mac, The Crazy World of Arthur Brown. June 28-29, 1968. Shrine Auditorium, Los Angeles (AOR. 3.75). © Victor Moscoso. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

<11> Here the delightful and visually overwhelming design allows for a denser, more successful movement of figures through space [ FILM 4].

<12> But, as Annabelle first demonstrated, it is the tri-color (red, yellow and blue) that best activates the four-dimensional effect. With this in mind, Moscoso returned to the idea in earnest in mid-1968, designing his four four-dimensional masterpieces. Though all four were commissioned to ostensibly advertise, they come across first and foremost as works of art that explore the issue of time. Like his fellow psychedelic poster-makers, Moscoso's work extended well beyond the context of advertising rock concerts. Like them, he used the contexts of commercial, cultural, and rock advertising as opportunities for independent artistic exploration. It often seems as though the event or product is completely incidental to the aesthetic "meaning" of the work. Like his colleagues, Moscoso was exploring the limits (or lack thereof) of graphic art itself. While the earliest of his 4D experiments were produced for rock concerts, his most successful examples were produced for a variety of different contexts. Therefore, Moscoso's experiments ought to be understood more in terms of conceptual artistic exploration than in terms of "Rock Art," as is so often the case. Like 1967s The Joint Show exhibition and the Neon Rose series, Moscoso's 4D posters proclaim a certain artistic autonomy, asserting the artist's vision as central to the poster's meaning and purpose as art. Calling attention to their artistic legitimacy, Moscoso included them as part of his Neon Rose series - a travelling poster show and personal artist manifesto.

<13> Moscoso was commissioned to design the cover for the debut album by The Steve Miller Band, Children of the Future, released in June 1968. Both the front cover and the inner gatefold included off-set printing that would move under the proper lighting. The related promotional poster reprises the theme of the quintet as a flock of flapping bird-men.

FIGURE 5 - Victor Moscoso. The Steve Miller Band Children of the Future promo. 1968 (NR-23). © Victor Moscoso. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

<14> Moscoso's poster primarily engages through its sense of movement, as the letters are largely overshadowed by the more adamant avian antics above [FILM 5]. Surprisingly, the shifting lighting actually makes the poster easier to read, as the shadows that emerge with the flickering of the lights draw attention to the letters that are otherwise hidden in plain sight at the bottom. This was the 4D design most frequently seen "at work" thanks to a number of in-store promotional displays that were created, in which the poster image was reproduced within a three-dimensional cardboard armature that could be lit with a tri-color strobe to create the sense of movement.

<15> Moscoso's most filmic 4D poster appropriately celebrates Pablo Ferro Films - pioneers of quick-cut editing, split-screen shots, and movie title design.

FIGURE 6 - Victor Moscoso. Pablo Ferro Films. 1968 (NR-22). © Victor Moscoso. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

<16> Like Ferro's cinematic developments, Moscoso's poster unfolds in a multi-shot narrative, arranged across six scenes, like film stills… though hardly remaining still [FILM 6]. Rather than words, it is the compositional format and its animation that advertise the film company. A little story emerges about a violin busker and the magic transformation of a flower offering into a butterfly woman. The filmic emergence of the butterfly hearkens back to the origin of the 4D posters in Annabelle's butterfly dance, which itself originated in film. Though ostensibly arranged sequentially like film, the story appears in six simultaneous frames of a larger narrative. Time is both presented and folded in on itself, making the processing of this image itself an exercise in temporal transcendence. Time does not stand still, but remains in perpetual motion, though not in an uninterrupted single-direction. Moscoso evokes time, shows time, and then ultimately undermines its very chronology. The effect is like a psychedelic nickelodeon polyptych that challenges one to take in the larger story through the simultaneous repetition of six connected micro-narratives. A clear advertising message is not really the intent of the poster, which moves to speak the visual language of Ferro's film-work, translated into a psychedelic dialect for the poster to speak. In concept and execution, this reveals previously-unrealized possibilities for the poster as art. Space is invoked and then revoked, a narrative is set and then undermined, as a single "film" is shown but in simultaneous sections. It is like a film, but not. It is like a poster, but not. Negotiating between the two, this image somehow manages to transcend the norms of both media.

<17> With the text so finely embedded into the poster as to be difficult to even find, the Pablo Ferro poster becomes essentially about temporal and cinematic effects performed across two-dimensions. Tucked into the green cloudy frame above each scene, little pink arcs appear as though glimpses of a text-embedded film reel that spins amidst the cloudy bubbles. Beginning at the upper left and proceeding across and down (echoing the flow of the visual narrative), it appears as though a single pink reel is gradually rotated for each of its six appearances (above each scene). Only upon considering the notion of the disc turning and moving sequentially in time, spooling out the words, can one discern that it carries the slogan - "Pablo Ferro Films Versatility And Love." Both the text and image of the poster engage in the movement of time and movement in time. It is a manifesto, asserting a poster's capacity to "compete" with film itself as a temporally narrative medium. The poster can create time and travel time. It has transcended itself....entering the realm of film, music, and poetry.

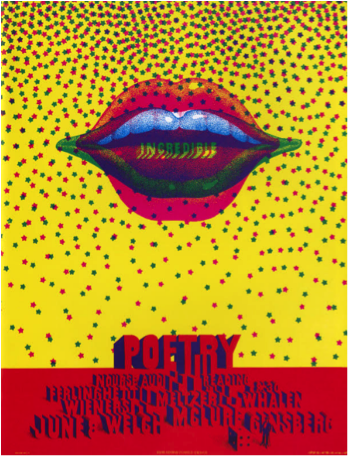

<18> To advertise a poetry reading on June 8, 1968 at San Francisco's Nourse Auditorium, Moscoso presents visual poetry in motion.

FIGURE 7 - Victor Moscoso. Incredible Poetry Reading. June 8, 1968. Nourse Auditorium, San Francisco (NR-24). © Victor Moscoso. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

<19> With a who's-who roster of counterculture poets, including Ferlinghetti and Ginsberg, the reading promised to be as incredible, as the poster that heralded it. Amidst a flutter of falling stars, a great, hovering mouth opens and closes in repeated intonation of the "incredible" nature of the event [FILM 7]. The solid, blocky letters of the poets stand in bold relief below, while the moving lips and falling stars activate the image's temporal poetics and poetic temperament. In concept, this is relatively similar to Moscoso's final 4D poster, made in conjunction with this 1968 touring show of the Neon Rose series, that he entitled The San Francisco Poster 1966-1968.

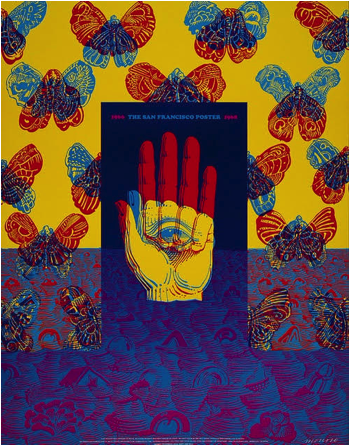

FIGURE 8 - Victor Moscoso. The San Francisco Poster 1966-1968 (NR-26). © Victor Moscoso. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

<20> Moths flutter upward, as though emerging from a floral sea, while a great hand hovers in the center [ FILM 8]. As the moths flap their wings, the hand opens and closes, revealing an eyeball in the palm. The eye stares at us persistently, despite being repeatedly covered and uncovered by the sound of one hand clapping. It challenges us to look unflinchingly, to stare back and take in all the seemingly improbable movement going on. This play of time is the ultimate visual trip of the psychedelic poster - taking it farther than the poster had ever gone before. Parting lips and opening hands perform the visual poetry of the poster's temporal apotheosis as it reaches the fourth dimension.

<21> Beginning again in the 1990s, Moscoso has produced additional 4D posters, though he has not displayed them as such formally. 1997's I Want to Take You Higher exhibit of psychedelic posters at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is heralded by an Anglo-American hippie butterfly semaphore wave, while 2002's solo exhibit at San Francisco MOMA invokes the athletic siblings of the strongmen (NR-25 and FD-66) flanking Annabelle's dancing descendent (FD-61).[ix] Moscoso is still playing with the dimension of time, and the time-motion effect now takes on an element of conscious self-reference to his own pioneering temporal explorations. The modern 4D works attest to Moscoso's awareness of the importance of his experimental 4D poster legacy, even if this message has up to now been largely lost on the majority of viewers.

<22> Equally important as the poster design itself was the creation of a means to successfully show it in all its kinetic glory. It was not just a question of how to make them, but also how to let people see them "at work." The happy accident of Hesseman's hallway lights would be cumbersome to reproduce. Moscoso devised a light-box - essentially a tri-color strobe - to allow the motion to be regularized and its effects maximized. It was used with several of the 4D posters in his 1968 Neon Rose touring show. As such, the only time these were seen under "proper" lighting conditions was in the context of an art exhibit, and a relatively short-lived one at that. This left most people to baffle their way through these posters' visual invitation by perhaps wearing 3D movie glasses while blinking rapidly, as suggested at the bottom of Moscoso's final 4D poster (NR-26). Perhaps in an effort to help struggling viewers see the motion, the poster reports that "This poster will appear to move. In a dark room flash red then blue light. In light room blink left-right through red-green (3-D) glasses." Despite the limited number of light-boxes made, Moscoso clearly wanted people to notice the posters' four-dimensional qualities. Similarly, a "Dance" poster from 1967 by Terre Art Studios in San Francisco explains at the bottom how to best view the red-and-blue overprinted bell-wielding dancing woman - "Use red and blue alternately flashing lights for a full animated effect - or use glasses with red/blue lenses."

FIGURE 9 - Terre Art Studios, San Francisco. Dance. 1967.

<23> Clearly the idea was in the air, but Moscoso is the artist who ran with it.

<24> In regard to the element of time, Moscoso's 4D posters constitute a radical conceptual leap - essentially transmogrifying the poster into something that essentially transcends its traditional self - a psychedelic apotheosis of the poster as a temporal means of visual communication. When viewed under the requisite lighting conditions, they become like flip books fed through a loop so that they remain in a state of perpetual motion. Time is simultaneously presented as both demonstrably linear and confoundingly circular. Ultimately, the posters become about time as much as about anything else, particularly since they are often difficult to read under the shifting lights. After even a few seconds of staring at the moving images, one cannot help but be hypnotized by the ritualized, ceaseless repetition of motion - like a visual mantra, endlessly repeating a pattern of movement that is simultaneously engaged in the performance and suspension of time. As such, they become mandalas for a sort of psychedelic visual meditation, challenging one to travel from fascination through dizziness toward an almost meditative calm, as the action continues around and around in a constant and continuous cycle, back and forth through time (like a ritualized or meditative repetition). In zoning-out, one might Zen-out as well. Perhaps this takes the poster (or at least its viewer) into the fifth dimension […].

<25> The point of many a psychedelic poster is to play with the mind and the mind's eye - to confound cognition of what the eye sees. But Moscoso's posters are exceptional in the manner in which they play with the eye's mind. Here it is less what one sees, but how one actually sees it that is new and "psychedelic." The imagery and "narratives" are relatively simple and easy to discern. Unique here is the actual filmic characteristic of the posters. Like film, Moscoso's 4D posters are two-dimensional works whose essence is performed in the fourth dimension. They are both adamantly and integrally temporal works of art, without any stopover in the spatial third dimension. But, film must physically move through a projector in order to demonstrate motion. Traditionally, the poster is stationary and not physically "time-sensitive." But, Moscoso's 4D posters are sensitive to time. As posters, they do so without themselves moving, but rather through the manipulation of the perception of the images through changing external factors, in this case the lighting configuration. Moscoso's 4D posters are unique in that they are fully conceived and produced with the exact four-dimensional operation not only in mind, but inscribed within the object of the poster itself. Yet, they remain decidedly posters - two-dimensional works of graphic art on paper. Unlike a spooling film reel, a poster does not physically move. But for the changing of a non-material extrinsic factor - lighting - the poster performs its temporal exploration entirely within its surface composition. A truly four-dimensional poster - one that is both sculptural and kinetic - would become something that can no longer be termed a poster. This being the case, it would be difficult to conceive of a bolder and more successful conquest of time than was achieved in Victor Moscoso's 4D designs which take the poster on its wildest trip of all - the trip through time.

<26> Within the growing body of publication on psychedelic (and Rock) posters, Moscoso's experiments in motion have generally gone un-acknowledged. [x] Equally, these posters have gone unmentioned within the substantial body of scholarship on light art and kinetic art.[xi] Despite their unquestionable importance in the experimental evolution of poster art (and graphic design in general), their marvelous moving nature has only recently been noted, or perhaps even realized. This is largely due to the very specific lighting conditions under which the posters appear to move and the fact that they have rarely been displayed under these requisite conditions. The lighting has been difficult to reproduce, as only one original lightbox is known to have survived the last half-century…and it is broken. [xii] As a result, few people have seen these posters perform time in all their glorious four-dimensional poetics. Without this lighting, the posters' true nature and importance cannot be (and has not been) fully understood. For this reason, these posters - the culmination of the psychedelic poster's ethos of experimentation and transcending expectation - have not been suitably appreciated. But how could they, if they have seldom been publicly visible under optimal lighting and have not been thus documented in film? Scholars, collectors, and aficionados are exonerated for oversight of something that was never in sight. These posters have only been known and accessible through photographs, which do not reveal the sense of motion or time. Indeed, photographs reduce the impact of the images, making some of the posters appear somewhat heavy-handed experiments in overprinting. Only through viewing them first-hand in real-time or watching the motion captured in archived film can one truly grasp these posters for what they are - artistic explorations of time.

<27> It is no accident that the two published references to this phenomenon both appeared recently, in the aftermath of one of the few public displays of some of the posters under moving lighting conditions since the 1960s.[xiii] The Denver Art Museum's sumptuous exhibition The Psychedelic Experience: Rock Posters from the San Francisco Bay Area 1965-71 (March 21 - July 26, 2009) proved to be a watershed moment in the study of these time-shifting posters.[xiv] In a brilliant curatorial decision, three of them (NR-23, 24, 26) were shown under the lighting conditions (back-produced from the surviving original light-box). Hands, lips, and wings were visually activated in public for one of the first times in decades, allowing viewers to marvel at Moscoso's bold temporal experiments. This opportunity was, unfortunately, somewhat mitigated by the placement of the posters in a small alcove to the side near the exit that was easily missed by the overwhelming majority of visitors overwhelmed by the exhibition's visual overload. It was enough, however, to bring these posters' dynamism to my attention, among others. As Moscoso notes, "not too many people are hip to that."[xv] However, several of Moscoso's 4D posters had already been ingeniously installed in D. Scott Atkinson's exhibit High Societies. Psychedelic Rock Posters of Haight-Ashbury at the San Diego Museum of Art (May 26-August 12, 2001). [xvi] Displayed in shallow alcoves, the posters were lit with alternating red-blue lights, but the source of the changing lights was not visible - only the moving posters. They appeared to move without the cause of their movement being apparent. Moscoso particularly enjoyed this installation of the posters because it added the element of surprise. He recalls watching a woman silently mouth "Oh my God!" when she rounded the corner and first saw the posters moving. "It caught people by surprise. I blew their minds." [xvii]

<28> Due to their unacknowledged historical significance, and the infrequency of their display, it seemed imperative to demonstrate their temporal qualities in an exhibition focusing on the artistic achievement and importance of this psychedelic poster movement. Visual Trips: The Psychedelic Poster Movement in San Francisco, at the Vicki Myhren Gallery, University of Denver (October 3-November 16, 2014) was perhaps the first exhibit to adamantly highlight the 4D posters' significance.[xviii] As confirmed by Moscoso in an April 2014 conversation, Visual Trips was likely the first time ever that all of his original 4D posters were exhibited under their animating lighting conditions. In conceiving and curating Visual Trips, I determined from the very beginning that Moscoso's four-dimensional posters should serve as the exhibit's centerpiece. This decision posed a series of practical challenges - not the least of which was back-producing the exact particulars of the requisite lighting conditions to make the posters "dance." Fortunately, Dan Jacobs (Director of the Vicki Myhren Gallery) was enthusiastic about the idea, and technical wizard Kelly Flemister was able to create the effect using timed LED lights. This was far preferable to an unwieldy light wheel using colored gels. Necessary to the process, blue LED lights had proven to be the most difficult to master, and had only been successfully developed in recent years. In felicitous synchronicity, while Visual Trips was on display at the Vicki Myhren Gallery, Shuji Nakamura, Isamu Akasaki, and Hiroshi Amano were awarded the 2014 Nobel prize in physics for the invention of the blue LED. Without this development, Kelly would not have been able to produce the lighting necessary to illuminate Annabelle's butterfly dance.

<29> The initial idea for the Visual Trips exhibition was to organize it around a central "black box" room in which the 4D posters would be displayed under proper lighting. While spatially asserting their central importance, this arrangement, however, would have made it easier to miss these posters, as one could simply walk past the room without entering. So, I opted to situate them in an un-avoidable location where they could not be missed or bypassed. Not merely showing the posters, we forced attendees to see them by placing them along either side of the hallway through which visitors exited the exhibit [FILM 9 and FILM 10]. As such, they were the physical and conceptual culmination of the exhibition's articulation of the artistry of this psychedelic poster movement. One couldn't miss them. Additionally, this "way out" way out of the show contextualized one of the first posters seen in the exhibit - Moscoso's Joint Show poster (NR-25) in the opening section outlining the artists' elevated artistic aspirations. When initially seen by visitors, this poster appeared as a tame experiment in overprinting. But, upon exiting the 4D section of the exhibit, it was directly visible again, now even more contextualized within the larger ethos of artistic experimentation, particularly Moscoso's dramatic exploration of posters' temporal potential.

<30> The fact that the 4D section was consistently praised as a "revelation" and a highlight of the exhibition demonstrates the importance of displaying these posters in their intended lighting conditions. Only upon seeing the posters move in real time, were visitors able to fully grasp their bold, experimental nature. And grasp it they did! They also gasped, gawked, and grinned. Popular praise by attendees and the news media alike regularly highlighted the "trippy" moving poster group as one of the real standout features. Of course it was! Not only are the 4D posters striking, but almost no one had seen them before. Nearly fifty years after their creation, they were still something "new" to multiple generations of gallery attendees. Demonstrating this phenomenon was among the major contributions of the Visual Trips exhibition. Considering the widespread "wow" factor prompted by these posters in 2014 - almost half a century after their creation - it is striking just how "forward" Moscoso's experiments actually were at the time. Taking posters to a new frontier, transcending their two-dimensional poster-ness, Moscoso's 4D designs crossed over, beyond the confines of traditional graphic art. Where could it go from here? Perhaps this helped point to digital as the next frontier…onward toward new artistic and conceptual horizons…the very spirit and essence of psychedelia.

<31> In keeping with the embrace of play, experimentation, and discovery that marked the advent of the 4D poster with Anabelle's butterfly dance, the sense of surprise and accidental revelation accompanied us in the preparation of the Visual Trips exhibit. Once we had the lighting developed, like kids in a candy store, the gallery staff and I set out to explore what other surprises might emerge from testing various other posters under the lights. Though not designed to "move" under this lighting, some posters did demonstrate very interesting and dramatic visual shifts as the lights alternately cancelled and revealed different colors and forms. Among the more deliciously shifting images thus discovered were Moscoso's 1967 "Death and Transfiguration" poster for Webb's in Stockton (NR-13) and his 1969 KMPX design (NR-20), both of which performed remarkable changes under these lighting conditions. The most felicitous example was a unique overprint of two of Moscoso's poster designs from early 1967 (NR-2 and NR-10). The product of the general ethos of experimenting with overprinting, not unlike the original use of Annabelle, the double image provides a dense visual beat. Numerous uniquely overprinted posters with deeply psychedelic ineffability were also made at the time by the East Totem West Company. [xix] While the overlay of NR-2's dancing woman and NR-10's perspectival portals was interesting in its visual instability, we were not prepared for the dramatic transformation of the poster under the shifting lighting [FILM 11]. With their oppositional coloration, the two poster designs alternately emerged and receded, creating a dynamic, strobic, almost cinematic beat between the two images dancing in-and-out of view…over and over again. Though not intentional, the effect was similar to that intentionally fashioned with the 4D posters. Emphasizing this sense of play and possibility, we opted to include this overprint in the exhibition's 4D section near its butterfly-dancing sibling. The happy accidental discovery of Annabelle's flight, and Moscoso's intentional development of this potential for movement in posters, inspired our own intentional (if spontaneous) exploration of further accidental possibilities.

<32> During the Visual Trips exhibit, the 4D section was frequently filmed on peoples' i-phones, creating some of the first visual records of the posters dancing, flapping, waving, and causing general visual mayhem. But such films are generally not available for public access, until individuals upload their shaky footage to Youtube, Facebook or other social media. But these posters deserve to be displayed properly in all their kinetic glory. This underscores the importance of digital archiving of these posters' movement, since the lighting conditions are no longer available now that Visual Trips has closed. We thus deemed it necessary to film the ephemeral effects of the posters "moving" under their intended lighting. This documenting, archiving, and sharing serves not only to record and preserve, but perhaps more importantly, to open up Moscoso's experimental posters to greater study and appreciation, allowing them to assume their rightful place in the history of experimental graphic design. The publication of this article prompted me to make available on YouTube some of this archival film shot during Visual Trips. Only with such digital archiving and publishing can the full importance of these posters be made readily apparent to scholars and the public alike - finally enabling legitimate scholarly analysis of these radical experiments in graphic art and design - the ultimate transcendence of the poster's identity and function beyond advertising and into the realms of art and poetry.

<33> In April 2014, I asked Moscoso about his conception of the 4D posters. He responded animatedly, "Just this week someone (I cannot recall who) noted the four-dimensional effect of the posters. And now you - the second time this week. And all the years prior I never heard anyone say this. I've known it all along."[xx] Now, we can all know it and can see it all - dancing, flapping wings and hands, and incredible visual poetry in motion.

All FILMS: Video by Kelly Flemister. 2014. Courtesy of the Vicki Myhren Gallery, University of Denver.

FIGURE 1 and FILM 1 - Victor Moscoso. The Doors, The Sparrow. May 12-13, 1967. Avalon Ballroom, San Francisco (FD-61).

FIGURE 2 and FILM 2 - Victor Moscoso. Youngbloods, Siegal Schwall Band. June 15-18, 1967. Avalon Ballroom, San Francisco (FD-66).

FIGURE 3 and FILM 3- Victor Moscoso. Joint Show. July 1967. Moore Gallery, San Francisco (NR-25).

FIGURE 4 and FILM 4 - Victor Moscoso. The Who, Peter Green's Fleetwood Mac, The Crazy World of Arthur Brown. June 28-29, 1968. Shrine Auditorium, Los Angeles (AOR. 3.75).

FIGURE 5 and FILM 5 - Victor Moscoso. The Steve Miller Band Children of the Future promo. 1968 (NR-23).

FIGURE 6 and FILM 6 - Victor Moscoso. Pablo Ferro Films. 1968 (NR-22).

FIGURE 7 and FILM 7 - Victor Moscoso. Incredible Poetry Reading. June 8, 1968. Nourse Auditorium, San Francisco (NR-24).

FIGURE 8 and FILM 8 - Victor Moscoso. The San Francisco Poster 1966-1968 (NR-26).

FIGURE 9 - Terre Art Studios, San Francisco. Dance. 1967.

FILM 9 - Visual Trips - left wall of 4D section. Vicki Myhren Gallery, University of Denver.

FILM 10 - Visual Trips - right wall of 4D section. Vicki Myhren Gallery, University of Denver.

FILM 11 - Victor Moscoso. Overprint of NR-2 and NR-10.

Notes

* First and foremost, thanks to Victor Moscoso for generously sharing his information and insight. Much of this formulated during the process of putting together and exploring the Visual Trips exhibit in 2014. There are a number of institutions and individuals without whose knowledge, assistance, kindness, and wisdom, neither the exhibit nor this article would have transitioned from idea to actuality. In particular, I thank the University of Denver, the School of Art and Art History, the Vicki Myhren Gallery, Dan Jacobs, Sabena Kull, Nessa Kerr, and the student staff of the VMG, Paul Harbaugh, David Tippit, Mike Storeim, Bob Carlsen, Al Bauer, Sonja Briney, Toby and Dave Montgomery, and Alice Bauer. Multi-colored accolades to Kelly Flemister for her peerless lighting expertise and dauntless experimentation that allowed us to recreate the lighting conditions. I thank Scott Howard for his thoughtful, gracious, and patient editorial excellence. Thanks Alice, Francesca, Gabriella, and Serafina for being my four dimensions.

[i] Popular slogan of the late 1960s, popularized by acid guru Timothy Leary in 1966 and opening lyrics to The Beatles' "Tomorrow Never Knows" ( Revolver LP. Released August 1966).

[ii] Wes Wilson. Trips Festival handbill. January 21-23, 1966. Longshoremen's Hall, San Francisco.

[iii] Telephone conversation April 30, 2014.

[iv] Note on the poster numbering. FD refers to the Family Dog series of concert posters for the Avalon Ballroom and NR refers to Moscoso's Neon Rose series.

[v] Telephone conversation April 30, 2014.

[vi] For the film, see: https://www.youtube.com/

[vii] Telephone conversation April 30, 2014.

[viii] Telephone conversation April 30, 2014. Hesseman and Moscoso's initial conversation must have been mid-to-late May 1967. FD-61 is for shows May 12-13 and the next 4D poster (FD-66) is for concerts June 15-18. Howard Hesseman is an actor who is perhaps best known for his role as DJ Dr. Johnny Fever in the sitcom WKRP in Cincinnati that ran from 1978-1982. Hesseman had worked as a real DJ for legendary "hip" radio station KMPX in San Francisco, for which Moscoso designed an excellent poster in 1969 [NR-20).

[ix] Victor Moscoso, Sex, Rock & Optical Illusions. Victor Moscoso. Master of Psychedelic Posters & Comix (Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2005), pp. 130, 133.

[x] Among the more substantive publications on psychedelic posters, see: Walter Patrick Medeiros, San Francisco Rock Poster Art: A Catalog for the October 6-November 21, 1976 Exhibition (San Francisco: The Museum of Modern Art, 1976); Eric King, The Collector's Guide to Psychedelic Rock Posters, Postcards and Handbills 1965-1973 (Berkeley: NP, 1980 with numerous updates); Paul D. Grushkin, The Art of Rock. Posters from Presley to Punk (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1987); Gayle Lemke,The Art of the Fillmore 1966-1971 (New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1999); Ted Owen and Denise Dickson,High Art. A History of the Psychedelic Poster (London: Sanctuary Publishing Limited, 1999); Sally Tomlinson and Walter Medeiros, High Societies. Psychedelic Rock Posters of Haight-Asbury (San Diego: San Diego Museum of Art, 2001); Kevin Moist - "Dayglo Koans and Spiritual Renewal: 1960s Psychedelic Rock Concert Posters and the Broadening of American Spirituality"Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, VII (Summer 2004), 30 pages np; Amélie Gastaut and Jean-Pierre Criqui, Off the Wall. Psychedelic Rock Posters from San Francisco (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005); David H. Tippit, "The 1960s American Psychedelic Poster", in: The Pope Smoked Dope. Rocková hudba a alternativní vizuální kultura 60. let ( Rock Music and the Alternative Visual Culture of the 1960s), Zdenek Primus, ed., (Prague: Galerie hlavního mĕsta Prahy, 2005), 36-49; Sally Tomlinson, "Sign Language: Formulating a Psychedelic Vernacular in Sixties' Poster Art", in: Christoph Grunenberg, ed., Summer of Love. Art of the Psychedelic Era (London: Tate Publishing, 2005), 121-143;Victoria A. Binder, "San Francisco Rock Posters and the Art of Photo-Offset Lithography," The Book and Paper Group Annual, 29 (2010), 5-14; Kevin M. Moist, "Visualizing Postmodernity: 1960s Rock Concert Posters and Contemporary American Culture, The Journal of Popular Culture 43/6 (Dec. 2010), 1242-1265; Phil Cushway, The Art of the Dead (Berkeley: Soft Skull Press, 2011); David H. Tippit, "A Social History of the American Psychedelic Poster" and Scott B. Montgomery, "Psychedelic Rock Poster Art in San Francisco: Aesthetic Concepts and Characteristics" ("A pszichedelikus rock plakátművészete San Fransicóban: esztétikai konceptciók és jellemzők," translated by Mihály Árpád) both in: San Franciscótól Woodstockig. Az amerikai rockplakát aranykora 1965-1971 ( From San Francisco to Woodstock. The Golden Age of American Rock Posters 1965-1971) (Budapest: Kogart Kiállítások, 2011), 40-66, 100-165; Scott B. Montgomery, "Signifying the Ineffable: Rock Poster Art and Psychedelic Counterculture in San Francisco" in: West of Center: Art and the Counterculture Experiment in American Art, 1965-1977, Elissa Auther and Adam Lerner, eds. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 574-610.

[xi] Even Edward Shanken's magisterial Art and Electronic Media (London: Phaidon Press, 2009, 2011, 2014), while sensitive to the significance of the San Francisco experiments with light art, omits Moscoso's posters. See, esp. pp. 16ff. Otherwise thorough and thoughtful, Shanken cannot be held accountable for overlooking material that was not available.

[xii] David Tippit personal correspondence.

[xiii] The element of movement and time is addressed by both Tippit, 2011, pp. 50ff and Montgomery 2011, 134ff.

[xiv] Unfortunately, no catalog or publication accompanied this exhibit.

[xv] Telephone conversation December 8, 2015.

[xvi] See: Tomlinson and Medeiros, 2001.

[xvii] Telephone conversation December 8, 2015.

[xviii] While no formal publication accompanied the exhibit, the extensive wall and pull-out texts became the basis for an expanded analysis in the form of my book Visual Trips, currently in the final stages of preparation.

[xix] See: Alan Bisbort, The White Rabbit and Other Delights. East Totem West. A Hippie Company 1967-1969 (San Francisco: Pomegranate Art Books, 1996).

[xx] Telephone conversation April 30, 2014. However, see note 13 above.

Return to Top»