Reconstruction Vol. 16, No. 1

Return to Contents»

Programming (Bi)Cultural Memory: Remembrance, Reinvention, and Commemorative Vigilance at the Film Archive, Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision / Simon Sigley

<1> In Sites of Memory (1984-1992), French historian Pierre Nora argues that a nation's identity is rediscovered as a result of reconfiguring the rationality that makes up its 'memory realms'. Nora's work was shaped by the idea that memory today no longer functions as it once did. In premodern times, memory was spontaneously hailed, with ancestors remembered in 'the warmth of tradition, in the silence of custom' (1989: 7). Today, however, a historical sensibility has replaced such a rapport. History reconstructs from the remnants of material and symbolic culture what is no longer closely remembered. Memory sites emerge because memory realms are no longer directly, personally, and intimately experienced by people living in a condition of modernity, in societies subject to constant change and accelerating history. The 'acceleration of history' reveals the distance that separates real memory - an inviolate social memory that so-called primitive and archaic societies embodied - from history, which is how modern societies organise a past that constant change condemns them to forget (1996: 2). With modernity's insistent futurist drive, a counter thrust returns to ancient ways, as Mathew Arnold recounts in 'Empedocles on Etna' (1852),

"[…] we are strangers here; the world is from of old […] And we shall fly for refuge in past times,

Their soul of unworn youth, their breath of greatness […]"

<2> One consequence of this fundamental sundering is the advent of a 'commemorating era' and the importance of places (museums, archives, monuments) that maintain the vestiges of ritual and the 'sacred' in a disenchanted world. Modern memory, for Nora, is essentially archival, reliant on 'the specificity of the trace, the materiality of the vestige, the concreteness of the recording, the visibility of the image' (1996: 8). Inasmuch as memory is no longer intimately experienced as interiority, it needs to distinguish itself via various prosthetic attachments (places and traces), whose tangible role it is to remind us 'of that which no longer exists except qua memory' (1996: 8); whence the obsession with the archive that marks our age. Nora asks if any society has produced such deliberately voluminous archives as those struck by 'accelerating history'; a question arising not only because of the technical means of reproduction and preservation that mark the analogue and digital transformations of data storage and retrieval, but also because of a 'superstitious esteem' and 'veneration of the trace' (Nora 1989: 13) that compel societies interpellated by modernity 'to collect remains, testimonies, documents, images, speeches, and visible signs of what has been', as if such evidence might one day be summoned to appear before some historical tribunal (1989: 14). The establishment and evolution of the New Zealand Film Archive bears close witness to this summation, as the rest of this text will argue.

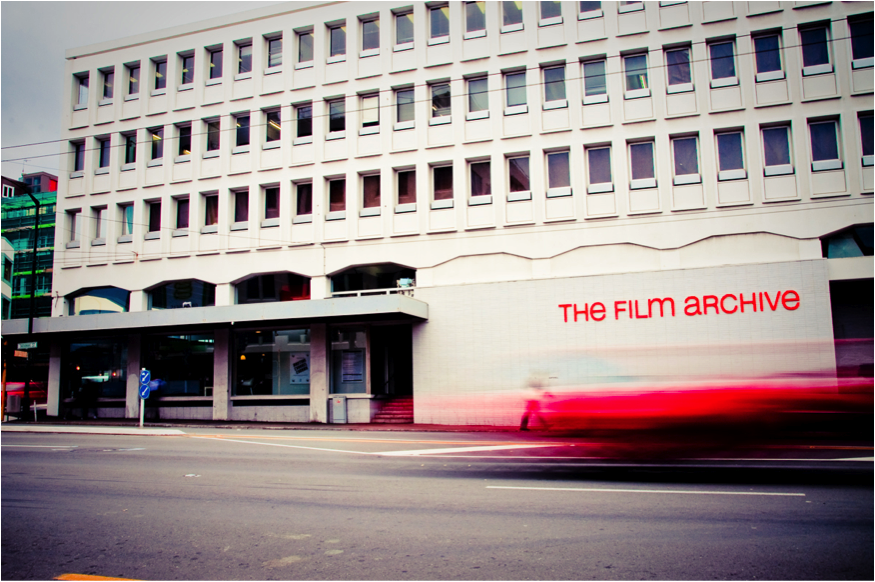

Figure 1: Self-generated publicity image of the NZFA (prior to its renaming in 2014 as Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision) in Wellington, 2012. Motion blur reinforces the notion of the Archive as a still and stable centre in a rapidly evolving world. This visual conceit neatly underscores Nora's point about the 'acceleration of history' and the Archive's commemorative vigilance in conserving the nation's audio-visual culture. Image courtesy of Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision.

Establishing the Archive

<3> Founded in March 1981 as an autonomous charitable trust, the Film Archive came into being at a time when New Zealand was coming to terms with the combined powerful processes of internal and external decolonisation. As the United Kingdom shed its waning Commonwealth connections in order to invest its future in the European Economic Union, New Zealand was forced to wean itself from intimate socio-economic and symbolic attachments to the 'Mother Country' and commence several fraught journeys: it sought new markets for its goods and services; rapprochement with Australia and the Asia-Pacific region; embarked on a delayed identity quest; and sought to understand what 'biculturalism' might mean and involve in terms of concepts of sovereignty. Biculturalism was the predominant mood established from the mid-1980s, shaped by renewed interest in the Treaty of Waitangi (1840), a Maori cultural renaissance, and bicultural initiatives.

<4> Pakeha masculine identity[i] found cinematic expression with the local success of Sleeping Dogs (1977), Roger Donaldson's film of C.K. Stead's novel, Smith's Dream (1971). As his name suggests, Smith is an 'Everyman' faced with a series of difficult existential choices, much like the nation itself. The film's commercial success and critical acclaim clearly spoke to these broader concerns, but it also contributed to the State's decision to provide funding and institutional support for a fledgling film industry when it established the New Zealand Film Commission (NZFC) the following year.[ii] Arguments advanced to persuade government to nurture an indigenous film industry included import substitution, job creation, and the construction of a national identity. Alan Highet, Minister of the Arts, addressed the last point explicitly in a speech he made in Parliament when introducing the legislation to create the Film Commission in 1977: 'We need our own stories and our own heroes. We need to hear our own voices' (Shelton 2005: 25). A voice from the margins responded. Maori identity was screened in Barry Barclay's début feature film, Ngati (1987), which proclaims in both diegetic and profilmic terms the need for Maori to take ownership of their material and symbolic property so that a community will endure and prosper.[iii] Women's identities found expression in various screen narratives, inaugurated by the television series Pioneer Women (1983).

<5> Re-examining the past so as to understand the present (as well as projecting itself into a future of its own making), the decision to create a film archive (and nurture a film industry) needs to be seen in the light not only of modernity and 'accelerated history', but also of these more specific social, economic, and cultural forces. It also needs to be seen as the result of the work of committed individuals and small 'ginger' groups who appreciated that film was fragile, expensive to store, and could be dangerous. 'Nitrate won't wait' became the evocative international slogan that galvanised energies towards the end of the 1970s and can be seen as the discursive mode that constituted the 'heroic' phase in the history of the Film Archive.

<6> Its first director, Jonathan Dennis (1953-2002), was well suited to the task of bringing the embryonic institution into the limelight. A former actor and assiduous Wellington Film Society member, he became imbued with the idea that film in New Zealand had to be saved from imminent disappearance (Shelton 2011). His initial awareness of the dire condition of the nation's film heritage was, according to his own recollection, [iv] a result of meeting Clive Sowry, an employee of the National Film Unit (NFU) who had developed a personal interest in the Unit's collection and spoke to Dennis of the 'Shelley Bay bunker'. Together they catalogued nitrate film held in an old WW2 army bunker in Shelly Bay on the Miramar Peninsula in Wellington. Their discoveries included such precious silent features as My Lady of the Cave (1922), Rewi's Last Stand (1925), The Te Kooti Trail (1927), and The Bush Cinderella (1928), all made by pioneering local filmmaker Rudall Hayward.[v]

<7> Prior to the advent of the Archive, film conservation and preservation in New Zealand were, as in many other countries, hardly a priority, hardly on the 'heritage' radar. Former television journalist, Lindsay Shelton recounts how he and Doug Eckhoff (then Head of News and Current Affairs with Television New Zealand) would produce the annual review of the year on television throughout the 1970s by simply taking original 16mm footage and recutting it to suit their story; ordinary and unconscious vandalism that demonstrates how little consideration was given to archiving the nation's audio-visual history (Shelton 2011).[vi] That conservation and preservation were among Sowry's personal 'hobbies' was a felicitous happenstance not widely appreciated. Initially, while at the NFU, he was an autodidactic archivist - teaching himself what needed to be done to preserve film. In a gesture redolent of antipodean bricolage culture, he paid his way to Canberra at the end of a self-funded club rugby trip to Brisbane in 1977 and spent a week visiting the Australian National Film Archives (Sowry 2009).

<8> Both Sowry and Dennis were recipients of small grants given by the QEII Arts Council in 1979,[vii] which allowed them to study preservation practices in the United Kingdom. Dennis' sojourn at the National Film Archives followed Sowry's but both visited several European archives; were observers at separate annual conferences of the International Federation of Film Archives; and, particularly in Dennis' case, began the important task of establishing personal relationships with other archivists, thereby joining an international network that experienced a period of accelerated global growth in the 1980s (Huston 1994: 3), as archives engaged in preserving and commemorating national film histories.

<9> This brings us to 'postcolonial' history and biculturalism; a period ushered in with the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975. The Tribunal makes recommendations on Maori claims for redress as a result of actions or omissions of the Crown that breach the Treaty of Waitangi (1840), often considered the founding document of New Zealand. As understood over the past 40 years, the Treaty 'may be imagined as instituting an ongoing negotiation, not likely to be brought to a closure, between concepts of sovereignty descended from those presented in the document of 1840' (Pocock 2001: 93).

<10> At a discursive and material level, biculturalism refers to changes that occurred as a result of attempting to incorporate 'traditional' Maori values, beliefs, and practices into predominantly monocultural modern institutions of European provenance. As Anne Salmond (1983: 316) has observed, the key term here, 'traditional', is ambiguous in that it has come to mean both the period that preceded European arrival as well as the time of contact; the latter, however, initially at least, leaves these traditions and culture largely and remarkably unaffected. European ethnography once posited 'traditional' Maori as living in a dreamtime, an eternal stasis whose entry into history was a direct result of European agency: 'This myth of the Frozen Maori persists in some European and Maori minds, downplaying self-directed change in Maori society both before and after contact, fossilising "traditional Maori" at circa 1769' (Belich 1996: 22).

<11> Within the specific instance of the Film Archive, the bicultural turn principally concerns mana tuturu (spiritual guardianship) and taonga Maori (cultural treasures), the formal procedures governing the deposit of and access to audio-visual material with significant Maori content, especially when copyright expires after 50 years and the material could enter the public domain. Barry Barclay devised these terms and drew on notions of 'traditional' Maori culture to justify their pertinence.

<12> As already noted, biculturalism pervaded the 1980s (symbolically reflected in the attribution of a Maori name for the Archive in 1985: Nga Kaitiaki o nga Taonga Whitiahua/Guardians of Treasured Images of Light), as the public sector embarked on a process of internal decolonisation in the wake of the Labour Party's electoral victory in 1984. During Dennis' tenure at the Archive, biculturalism was a passionate, personal, and rhetorical position, with no procedural manifestation in the constitutional structure of the Archive. Redressing this discrepancy was an early priority for Frank Stark when he became CEO in 1992, with, for example, both board and convocation membership reflecting a 50/50 split. The six-member board's bicultural division is strictly enforced while the convocation's is typically more loosely observed. The convocation (electoral college) is a self-perpetuating body comprising roughly 20 people that elects itself, meets twice a year, receives the Annual Report, and has a community-mandating oversight role (representing Maori interests and filmmakers).

<13> Internal decolonisation involved more than institutions of State, it was also personal. Jonathan Dennis' mea culpa and transfiguration occurred hesitatingly over time and was movingly expressed during a 1990 Canadian symposium on archives in the new information age:

"As a Pakeha New Zealander (of European descent) it became a time of confronting my own coloniser's conditioning. The institution I had been responsible for creating and establishing was still strongly rooted in its European and mono-cultural concepts and value systems. The question of how sensitively or otherwise we were dealing with living treasures belonging to indigenous people was still overshadowed by the colonial experience repeating itself. How much participation did Maori people actually have in the decision making, even on the McDonald films? We consulted but it was mostly me who decided" (1992: 64).

<14> What Dennis was stumbling towards in the mid-1980s had developed into a focussed programme by the mid-1990s. Entitled Te Hokinga Mai o nga Taonga Whitihua (The Returning of the Treasured Images), it involved cataloguing the Archive's Maori material into iwi groups;[viii] establishing storage protocols; discussing with relevant iwi which images it would be appropriate to release for screening; marae film tours;[ix] and a formal memorandum of understanding regarding the Archive's conduct when negotiating with iwi.

<15> The Archive's increasing sensitivity to the concept of Maori taonga[x] reflected the process of interior decolonisation as the nation's British connections were steadily diluted. 'Indigenous' elements began to occupy positions from which they had formerly been marginalised and to assume a new significance. The Mobil Oil-sponsored exhibition, Te Maori, which opened in New York in 1984, was a milestone in the burgeoning Maori cultural renaissance: a very successful début was followed by equally impressive receptions in three other American cities, after which the exhibition, now rebranded Te Maori: Te Hokinga Mai (The Return Home), arrived in New Zealand in 1986 and was exhibited in the four provincial capitals. Allan Hanson (1989: 896) notes that one consequence of the prestige generated by Te Maori was that:

"Maori and Pakeha New Zealanders alike took greater interest and pride in it and became more receptive to the idea of a nonrational, spiritual quality in Maori culture. While the point should not be overemphasized, the exhibition did have some effect in both strengthening Maori identity and increasing Pakeha respect for the Maori people and Maori culture."

<16> The exhibition catalogue, written by Professor Sydney Moko Mead, helped shape a new museal practice by redefining the notion of taonga as a 'highly prized object that has been handed down from the ancestors' (McCarthy 2011: 62). So construed, taonga became storage devices that dispersed narratives 'to descendants when the objects are viewed, greeted, handled, and wept over' (2011: 62). The emphasis here (pace Nora) is arguably a contentious one: a vibrant continuing imaginative connection between the past (of a cultural artefact) and the present (of a source community).

<17> The notion of 'source community' has affective and cognitive resonance in that it acknowledges not only 'the groups in the past from whom objects were collected but also their living descendants today' (McCarthy 2011: 5), and thus helps reshape relationships between objects and people in such institutions as museums, archives, and art galleries. The narrative resurrection, reconstruction, and redefinition of taonga as 'a highly prized object' (with continuing pathways to the ancestors who made them) has been a defining moment in the contested history and display of signs whose semiotic significance reflects ongoing settlement struggles between the primary (Polynesian) and secondary (European) migrants: whose stories will define contact zones of encounter; which national narratives will exercise dominion; whose Foucauldian 'regime of truth', institutionally articulated in memory sites, will power self- and societal understanding? The decolonising rhetoric that enabled the discursive resurrection of taonga, which accompanied Te Maori overseas and mobilised Maori engagement with memory sites, was a 'watershed' because 'the Maori people have controlled the destiny of their significant cultural property, their taonga, and have placed upon a peculiarly European institution their own particular feel and mana' (cited in McCarthy 2011: 65).

<18> Through the direction of Jonathan Dennis in the 1980s, the Archive began to explore how a small cultural organisation could take on board Maori values, beliefs, and practices. Rather than simply being an institution that preserved and conserved film, the Archive would actively promote itself as an embodied site where memory would be commemorated via a screening programme. The first such opportunity presented itself in 1983 when the National Museum organised Maori Art for America, followed by Nga Taonga Hou o Aotearoa: New Zealand in 1984; rare silent films shot by James McDonald and preserved by the Archive were screened for the first time together in June 1983, in association with the first exhibition (McCarthy 2011: 42). The Archive's Travelling Picture Show, which sought to make old films enduringly relevant as 'living objects' for diverse audiences, first went to the Taranaki Museum to present several silent films shot in New Plymouth in 1912.[xi] Dennis remembers hearing of film as 'living objects' (a term that recognises transcultural understanding of what constitutes a 'highly prized' filmic artefact) during his meeting in Paris with Mary Meerson, Henri Langlois' partner and co-conspirator at the Cinémathèque française. The commemorative function of 'living objects' was noted as being especially poignant when the Archive travelled to distant Maori communities so that the ancestors captured on film could be 'returned' from whence they came.

<19> An account of one such excursion to Koroniti marae on the Whanganui River appeared in the February 1987 newsletter of the Archive. The McDonald films, made at the behest of Dominion Museum ethnographer Elsdon Best on expeditions to the Gisborne and East Coast region, Rotorua, Ruatahuna, and the Whanganui River region (1920-23), were among the first that the Archive began restoring.[xii] They were in high demand and the Archive began touring them in 1985. After recounting the reactions, ranging from hilarity to silence, that accompanied the projection of Scenes of Maori Life (1921), the writer noted that:

"Far more profound and moving is the direct communication which the films open up between the living and the dead. The children in the film are identified as the brothers and sisters of the elders amongst us. The adults are their parents, aunties and uncles. […] After the film some of the elders talk to the group about the effect the films have on them, of seeing people they still feel spiritually close to on the screen, of the inheritance they have received, and the traditions they want to pass on. […] We all feel touched by the greatest gift our ancestors have handed down to us, their love, and their abiding presence with us."[xiii]

<20> What Sharon Dell, Maori Materials Subject Specialist at the Alexander Turnbull Library, is describing here is the almost spontaneous safeguarding of memory by a minority people in modern society; an enclave whose commemorative vigilance acts as a bastion against the sweep of history, which would consign their protected collective identity to yesteryear. As understanding and moving as such responses are, there are also problematic aspects to them, such as the ongoing positioning of Maori as stamp and seal of 'the authentic', the anti-modern 'other' whose essentially spiritualized culture and living ancestral connections compensate the material abundance but putative spiritual poverty of Pakeha. Traditional memory may have vanished as intimate everyday experience among peoples subject to modernity but here, at least, Walter Benjamin's 'angel of history', with his face turned towards the past, contemplating the storm of progress that 'irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward', seems to want 'to make whole what has been smashed'. [xiv]

Strategic exoticism

<21> The contemporary positioning and imaginative self-shaping of Maori as anti-modern other with a unique relationship to, and respect for, the environment and the past is, first and foremost, a discursive one, a reconstruction (more than a remembering) of traditional culture with material and symbolic consequences in the present. Atholl Anderson (2013: 48) has noted what actually took place when the primary migrants first arrived in these islands void of humans.

"The nature of pre-European Māori environmental impact was, in its early stages, almost certainly typical of colonisation everywhere and at all times. Migration into new environments releases a powerful instinct to expand as rapidly as possible, using the richest resources with pitiless energetic efficiency. Evolutionary fitness drives lineage competition in the use of unowned resources towards levels of overexploitation described as the 'tragedy of the commons'."

<22> Widespread species extinction and deforestation occurred before 'environmental learning brought about the sort of adaptive change that is today often taken - by Māori and non-Māori alike - as somehow inherent to Māori culture' (Pawson & Brooking 2013: 25). To my mind, it does no disservice to contemporary Maori culture to recognise a dynamic adaptive ability to change in the face of fresh challenges and novel circumstances. Moreover, to persist in construing Maoris as idealized Pakeha 'Other', possessed of immutable ancestral wisdoms and a unique ability to enter into spiritual communion with the land (like Australian Aborigines or Native American Indians) simply prolongs colonialist and anthropological representations, rather than acknowledging flexibility and sophistication during the colonial period of intense contact.

<23> While the hugely successful Te Maori exhibition was, indeed, a watershed in several respects, ushering in substantive changes in museum culture, engendering pride in tribal art, and helping Pakeha along a bicultural path, what form of Maori culture is here recognised and celebrated? Nicholas Thomas (1994: 185) notes that the descriptions in the exhibition's catalogue 'lean toward a construction of Maoriness as mystical and spiritual', and quotes Professor Mead's prescription from the catalogue: 'The Maori psyche revolves around tribal roots, origins, and identity.' Moreover, while most of the exhibition material was from the nineteenth century, hence post-European contact, a period of irreversible and rapid change, 'it was unambiguously associated with a stable, authentic and radically different social universe that is characterized particularly by its holism, archaism and spirituality' (1994: 184).

<24> The rediscovery, or reconstruction, of traditional Maori culture for the purposes of Treaty negotiations called forth a form of 'strategic exoticism'; a process that transforms generalised cultural differences attributed to 'indigenous' peoples, such as 'authenticity', 'marginality', 'uniqueness', and 'spirituality', into commodities to be exchanged and consumed by foreign and domestic audiences. International tourism is an obvious industry for variants of the post-colonial exotic, but so too are nostalgic New Zealanders (both Maori and Pakeha), as well as archives and related civic laboratories, usefully viewed as machineries 'implicated in a shaping of civic capacities' (Bennett 2005: 522) and involved in reshaping national identity. The process whereby Maoris are reconfigured as peoples with reserves of traditional memory but little historical capital comes easily - as Sharon Dell's example above makes clear. But she is far from being a lone voice.

<25> A prominent Maori filmmaker, Merata Mita (1942-2010), addressed the same Canadian symposium as Jonathan Dennis. During her presentation, she protested at the colonial procedures that had mythologized her people's culture so that it became 'another vehicle of cultural oppression alienated from genuine indigenous experience' (1992: 74). 'Genuine', like 'indigenous', is a complex descriptor fraught with semantic and historical traps: whence does it emerge, whither go, and how does it become less than itself, that is, counterfeit or imitative? In what terms does Mita describe 'genuine indigenous experience'? How does she respond to the moving images of her people?

"With love and profound appreciation, I nurture and express their spirituality. It is first nature to me, not second, and has given me my way of seeing the world and of understanding that, in order for our needs to be met, we must first meet the needs of the earth. At home in Aotearoa, I greet the images of my ancestors verbally and speak to them as they come forth on the screen. For I know that while they have passed on, their images still live and are very much alive" (1992: 73).

<26> Mita's description of the 'genuinely indigenous' is a perilous understanding that seems to reify and introject earlier colonial and anthropological descriptions of 'traditional Maori society', circa 1769, which is to say just before regular contact with Europeans ushered in irrevocable change. But is the history of colonial encounter best represented as a Manichean duel 'between the indigenous people and the imperialist forces, to see which one will be able to culturally appropriate the other' (Sahlins 1993: 13)?

<27> While Mita's 'spiritualized' understanding of indigenous difference is met with scepticism as to its verisimilitude by contemporary cultural anthropologists and historians, conceptual displacement (biculturalism within the new museology) has shifted the hierarchy of values that formerly prevailed within such civic laboratories, those 'machineries' which fashioned 'cultural objecthood and the governance of the social' (Bennett 2005), and that now function as instruments for the promotion of cultural diversity; 'laying out the social as a set of equivalent differences to be tolerated as equally valuable' (Bennett: 540). Mita also railed against cultural institutions that showed insufficient respect for an emic perspective:

"It is arrogant and insulting to know that this happens and gives rise to mutterings that are growing louder that 'even our dead are not safe from them'. So from our side, we want our treasures to be handled with the right respect. We want to decide where and when they can be seen and who is to see them. We want to say how they should be screened. We want to have our ceremonies included as part of our own respect and homage to our past and to our ancestors. Indigenous people should have the right to determine the future of their own cultural heritage" (1992: 75).

<28> On the face of it, Mita is reacting rather properly to prior Pakeha cultural intrusion into and misappropriation of tribal history by so-called experts whose insufficient understanding of important Maori concepts, such as wairua (spirit, soul), tapu (sacred, prohibited), mana (prestige, power), and taonga (treasure, anything prized) prevented some of them from accessing a deeper knowledge of such words. But what of academic freedom and the Open Society? To what degree and extent should non-Maori academics be prevented from studying tribal history and culture? A meeting for writers of Maori tribal history in 1992 was restricted to people of Maori descent. One of the main topics concerned restricting tribal intellectual property to respective descent groups (Ballara 1996: 124). Those not connected by blood to a particular tribe would find their research opportunities severely curtailed. A prima facie case opposing 'academic freedom' to 'closed Maori culture' appears on the horizon. However, such an opposition between apparently incompatible worldviews may be establishing a straw man; the differences and difficulties in handling Maori tradition and whakapapa do not necessarily preclude critical examination by non-Maori (even if, in the first instance, it may still fall to Maori academics connected to the tribe to conduct such revisions of tribal traditions as novel perspectives make requisite). Longer term, Sir Tipene O'Regan (1992: 26) believes such proprietorial attitudes can be made less exclusive and

"that with the development of a wider understanding of the rules of studying Maori tradition, our communities will be much better placed to manage their cultural heritage in a wider New Zealand context. This will enable them to fulfil better the duties which fall upon them as a result of the rangatiratanga [chieftainship] provisions of the Treaty of Waitangi. This is necessary because the relationships involved with the wider community, in local government, catchment management, conservation and coastal zone management, really require a basic understanding, not only of tikanga [correct procedure], but also of history."

<29> Barry Barclay (1944-2008), a prominent filmmaker of both Maori and Pakeha descent, was another for whom the Film Archive had to be transformed in order to become a more fully developed bicultural contact zone, a 'space in which peoples geographically and historically separated come into contact with each other and establish ongoing relations' (Clifford 1997: 192). Barclay developed the Taonga Maori deposit form and the mana tuturu concept used by the Archive for material with significant Maori content. Briefly, both form and concept propagate the politics of identity as best practice and seek to essentialize traditional Maori culture by ensuring that mana tuturu (spiritual guardianship), of the moving images remains with the descendants of the people filmed - 'the extended family or clan group' (Barclay 2005: 117) - once copyright expires and the images could be released into the public domain.

<30> Copyright extinction and the public domain were causes of profound disquiet for Barclay given his spiritualizing of traditional Maori culture and his disdain for many aspects of Pakeha culture; what profane havoc might be wreaked upon these sacred objects once copyright expired? To prevent such a possibility, clause seven of Taonga Maori extends copyright protection and states that kaitiaki (guardians) and their descendants will exercise guardianship under the mana tuturu principle in perpetuity.[xv] In doing this, Barclay affirms the distinctiveness of whakapapa[xvi] and locates ethnic identity along bloodlines rather than on shared values or cultural practices, as 'it is Maori and Maori alone who bring "Maori spiritual guardianship" to the task' (2005: 123).

<31> Such identity politics runs the risk of oversimplifying the increasingly cosmopolitan and global environments in which we all live our lives, assembling hybridised, fluid, and fragmented self- and social identities from a cultural toolkit that blurs the older homogenous boundaries of class, gender, and ethnicity. His affirmation also seems to mythicize the past as compensation for disruptions brought on by modernity. Barclay would no doubt have found himself in strong disagreement with Rangi Kipa, a customary-trained young carver and sculptor, who declared that he found 'less and less relevance in defining myself by customary concepts, like "iwi" and so on… For the past 25 years we Maori have spent a lot of time and energy reconstituting ourselves within the customary construct to give ourselves validation for claims against the Crown. I'm over it' (McCarthy 2011: 184). This disenchanted Maori artist might be one of the many urban Maori for whom Maoritanga (Maori culture) is not construed primarily in terms of its difference from Pakehatanga.[xvii]

<32> In a book devoted to his films, Stuart Murray describes Barry Barclay as a religious filmmaker and points to several markers of his religiosity: his unfinished training as a seminarian in Australia; ideas about the value of community; a transcendent impulse that points towards the unseen; and the revival or remobilisation of foundational thoughts and feelings in the audiences that watch his films (2008: 7-8). This need to 'return' to culture and tradition in order to revive (or reconstruct) identity is a marked feature of some modern Maori, such as former Cabinet Minister and academic Dr. Pita Sharples.

<33> Barclay's most celebrated film, Ngati (1987), contains one of his best stagings of this need to return. The opening extreme long shot of sky, sea, and shore also features a bus slowly driving (left to right - figuring modernity) along a dusty backcountry road. It reaches the extreme edge of the frame and then (before exiting the picture completely) curves around the hairpin bend and moves 'back' as it trundles on to the small (and fictional) seaside town of Kapua in which the story will develop. The sequence displays Barclay's subtle mise-en-scène and stands in contrast to his blunter assertions (nineteenth century British migration as an 'invasion', for instance). Truculent assertions that have not produced those varieties of religious and nationalist fundamentalism noted by Edward Said (1994: xiv), but the difference is one of degree, not kind.

<34> While Murray is anxious not to paint Barclay as a 'cultural essentialist', his arguments are unconvincing. Barclay's creative retelling of traditional Maori culture carries just such essentializing seeds within its discursive practice. He and Mita both talk of the 'sacredness' of indigenous material culture (Barclay 2005: 105) and its profanity by such 'outsiders' as researchers, photographers, and filmmakers who engage in 'a form of theft' when collecting material 'from elders and others within the Maori world' (2005: 97). He describes the 'ancient laws of the Maori world' (2005: 95), as if they were immutable Mosaic tablets and believes that whenever Maori are recorded on camera 'what they are giving over is in some measure the taonga of themselves, their culture, their spiritual world, and those who are linked to them from the past and on into the future' (2005: 134).

<35> Another brick in the wall of 'traditional' Maori culture, as construed by Barclay, which informs the Archive's protocols regarding films with Maori content, is his notion of temporal relationships and film, differently appreciated by Pakeha and Maori. In what he calls 'Gradient A' films, those made by Pakeha,

"the film's principal period of glory is at the beginning of its life, at its premieres, during its main run … after that its gradient of vitality tracks downward … in terms of its vitality as a living document within the community… .That is what I call the Gradient A phenomenon. But with Maori work (with Maori work, that is, within the Maori community) the gradient tracks upwards. That is the feature of Gradient X" (2005: 102).

<36> While this definition conveniently downplays the importance of film archives, cinémathèques, and the many 'memory sites' constructed by Anglo-American and European cultural institutions under modernity, it does underscore the 'archaic' timelessness of Gradient X films; a temporality that increases their eternal value for the people related by whakapapa to those who appear in the film. Barclay later concluded that what the Maori subjects of the landmark television series he shot for Pacific Films (Tangata Whenua, 1974) wanted was an intergenerational (and timeless) copyright protection.

"And the wish was that those who were to be entrusted with the guardianship of the intangibles would be family, from generation to generation. Guardianship responsibilities were not to be passed to a national authority or institution or pan-tribal organisation or to 'Maoridom' or 'the people of Aotearoa'; they were to be passed to descendants of the people who had been filmed. The guardianship did not have to do with physical objects… I began using the phrase 'spiritual guardianship'" (2005: 111).

<37> Barclay here espouses a variant of Maussian 'archaism' - a closed Maori society dominated by kinship relations that define individuals and their connections with and obligations to one another. His argument seems to support Nicholas Thomas' contention that where 'contact has been most destructive, as in many settler-colonial nation states (such as Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii), resistant discourse may be structured by the discourse of the dominant … and that produces its own singular tensions' (1992: 227). One such tension may be described as 'ethno-Orientalism'; understood as 'essentialist renderings of alien societies by the members of those societies themselves' - a means of self-definition produced in dialectical opposition to 'the aliens' conception of the impinging Western society' (Carrier 1992: 197-98).

<38> Merata Mita rightly considers that Europeans have in the past mythologized 'indigenous' peoples (and, I would add, continue to construct - with the complicity of the same people - the post-colonial exotic),[xviii] but in their utterances Barclay and Mita seem similarly to fall into the same trap, by 'staging' traditional Maori culture as a rebooted version of the green, spiritual, anti-modern other; an other discursively produced and disseminated, as well as materially performed, for touristic delectation. The tourists in question being not only those jaded foreign travellers in pursuit of an elusive, exotic/erotic alterity but the home audience, too, for whom such fantastic figures offer fleeting respite and furtive refuge from 'accelerated history' and amnesia induced by the excision of memory, no longer 'lived in the warmth of tradition, in the silence of custom, in the repetition of the ancestral' (Nora 1989: 7).

<39> Staged marginality, which 'thrives on the retailing of cultural products regarded as emanating from outside the mainstream' (Huggan 2001: 95), provides exterior scaffolding and visible signs of what once was but is no more, whence Barclay's anxious attempt to give even the most humble testimony of the most ordinary person the potential dignity of the memorable: 'A Maori giving a taonga to a camera crew is presenting a gift to the world beyond the Maori world' (2005: 134).

<40> Whatever else Barclay may have been attempting to do (address false perceptions and rehabilitate Maori culture in the eyes of mainstream New Zealanders, often construed as racist), from a postcolonial critique perspective, he also engaged in 'product differentiation', alerting readers to those forms of generalised cultural difference that emerged as a result of nineteenth century European imperial expansion. It can thus be argued that Barclay's revisionist history, for all its rhetorical energy, encounters some of the same problems of essentialized spirituality as the ethnographic accounts that accompanied European colonization of much of the South Pacific; and runs the risk of romanticizing and embalming traditional Maori culture, seen as preserving inviolate elements untouched by modernity. In such an optic, the historically dynamic encounter with European beliefs, ideas, food, and technology seems not to have irrevocably transfigured the Maori world; sacred traces remain, represented in the 'living' relationships with taonga tuku iho [xix] (precious heirlooms) and the frequently staged ceremonial performances that hail them.

Branding the margins

<41> As a variant of the 'cultural entrepreneurialism' that found widespread expression in New Zealand in the wake of major public sector reforms, Barclay's approach has an oblique affinity with the many transformations of the State that resulted from the neo-liberal turn inaugurated by the Labour government following its election in 1984. These reforms gradually ushered in 'the becoming cultural of the economic and the becoming economic of the cultural' (Jameson 1998: 60). Throughout the 1990s, a series of official documents sought to quantify the economic contribution of cultural activities. A high-water mark was reached with The Heart of the Nation: A Cultural Strategy for Aotearoa New Zealand (2000), which used the language of the marketplace to describe identities, 'whether based on national affiliation or on transnational categories such as indigeneity, sexual orientation, or gender', as 'primary cultural assets' (Lawn 2006: 8).[xx] The aim was to brand New Zealand as a distinct destination that could be marketed to the world, thereby accruing competitive advantage.

<42> It is not easy for a small nation of some 4.5 million people whose GDP is largely reliant on selling food (principally dairy and carcasses) to create global brands: the All Blacks rugby team, filmmaker Peter Jackson, and pop singer Lorde command attention, as do certain elements of traditional Maori performance culture, like kapa haka. Such cultural figures add value to the nation and are 'routinely co-opted, coached and prompted to present a marketable national brand to the world' (Wedde 2005: 10).

<43> The immediate past CEO of the Film Archive, Frank Stark, is of the view that at a fundamental level (and in the eyes of the world), the unique component of New Zealand screen culture is Maori-based (November 2011). Clearly, such a view has affinities with the cultural entrepreneurialism and marketing strategies that emerged in the 1990s to brand New Zealand in distinctive ways. It also articulates a form of biculturalism that grew from the 1980s onwards. Furthermore, Stark's perspective seems infused with such commodity or marketing values as 'uniqueness', 'social cachet', 'taste', and 'originality', and could be interpreted as catering to an orientalizing view of New Zealand as exotic other; a view with a lengthy colonial history and postcolonial present. Emphasizing Maori-based screen culture as the most distinctive in terms of international recognition has some merit (especially for the nation's nearest neighbors - Australians - whose fondness for 'indigenously' themed films from this side of the Tasman Sea signals the perennial appeal of 'difference'); but Stark's view insufficiently recognizes how secondary (European) and tertiary (Asian) migrants have shaped (are shaping) the singularity of the nation's international screen image quite as much as the primary (Polynesian) migrants. In that regard, let us note Jane Campion, Christine Jeffs, Brad McGann, Jemaine Clement, Gerard Johnstone, and Jason Lei Howard as distinct Pakeha creators of cinematic figures that express the local at an international level. More recent Asian New Zealand creators include Roseanne Liang and Stephen Kang.

<44> The diffuse desire to accentuate traditional Maori culture as the official partner within the nation constructed as bicultural leads to malformations, distortions, and omissions. While the Maori cultural and economic renaissance that began in the 1970s contributes significantly to the varied cultural tapestry and richer economic life of the nation,[xxi] such a contribution should not obscure the multi-ethnic, multicultural present. In New Zealand's largest city, Auckland, one in every two people, for example, speaks a second language; an official language since 1987, only four per cent of the total New Zealand population speaks Maori.[xxii]

<45> The Film Archive's strong interpretation of official biculturalism as 'full partnership', rather than cooperation, has seen it implement a policy that strictly requires half the six-member board of trustees to be 'Maori', yet this cultural grouping accounts for only 15 per cent of the general population. The continuation of such a policy seems likely, if somewhat at odds with progressive democratic practice. While the convocation, the self-perpetuating electoral college that elects the board (and itself), has a looser form of bicultural observance with regards to the ethnic spread, in the 2012 Annual Report the Chair 'welcomed an influx of new members … ensuring that the balance between Maori and non-Maori membership mandated in the Constitution was in large part restored.'[xxiii]

<46> In other official cultural institutions, such as the venerable National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, with significantly more Maori cultural artefacts in its collections, such a 50/50 split of the eight-member board is not practiced. Moreover, when the Museums Association of Aotearoa New Zealand (now called Museums Aotearoa) adopted 50 per cent Maori representation on its governing council in the early 1990s, the experiment failed, with some Maoris calling the changes 'unrealistic' (McCarthy 2011: 100). Of course, semi-independent institutions are at liberty to chart their own course, especially as the Film Archive operates as an autonomous charitable trust and wears its record of independence proudly. It would seem, too, that the Archive has not experienced the 'unrealistic' changes noted above and is happy to continue with its strong interpretation of official biculturalism as full partnership, however anomalous such a position appears in multicultural New Zealand; a situation made all the more incongruous when one considers the economic and cultural weight of the Asia-Pacific region (most prominently China) for New Zealand's future development and prosperity. One wonders when representatives of the third wave of Asian migrants (who make up a quarter of Auckland's 1.5 million population) will take up positions within the convocation and thence onto the Archive's board, as they do on Te Papa's?

<47> The Archive also recognises Maoris as 'indigenous' (rather than as migrants or settlers, terms that would acknowledge their colonizing of the land, placing it within rather than outside history). Another term frequently used to describe Maori is tangata whenua, often heard in opposition to manuhiri.[xxiv] The discourse of indigeneity has its European history; it also has a Maori one, traced by Professor Andrew Sharp in his book Justice and the Maori. Sharp (1997: 8) notes how Maori activists' contact with the indigenous peoples of North America in the 1970s influenced their discourse.

"They spoke of being, like the American Indian, 'indigenous' to the land; and in this usage, to be 'indigenous' meant not just born and bred in a place but to be a member of a people who were in the place before all other peoples. It meant to be an aboriginal people - a people there from the beginning."

<48> The term 'tangata whenua' (people of the land) has been used to assert indigenous hegemony for the past 30 years and requires some parsing, as it continues to inform and influence a variety of discursive and nondiscursive practices (including Archive activity) in New Zealand.

<49> As Pocock notes (1992: 28), to claim that Maoris are indigenous (autochthones) to these latterly inhabited islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean opens such a claimant to ridicule. But let us eschew ridicule. For sympathetic readers, tangata whenua connotes 'a close and rich relationship between the meanings of land and birth' (1992: 29) woven from the polysemy of the term whenua, 'understood to mean both land and placenta, thus making the land a birthplace and a source of identity' (1992: 28). This self-shaping metaphor needs to be situated within a lengthy history of stubborn resistance to the many ingenious (and sometimes violently rude) methods used by the secondary migrants to usurp the primary migrants of much of their whenua and mana. It establishes a rhetorical foundation upon which more political claims to rights, which the Treaty of Waitangi (1840) is believed guarantee, can be asserted.

<50> Still, mythologising Maori presence as 'indigenous' and their culture as timeless - a dreamtime figured as poiesis - needs to be understood, I believe, as staged marginality, with significant material and symbolic outcomes. It provides an ingenious foundation from which to assert primacy, or what Edward Said called 'an aspiration to sovereignty' (1994). Said suggested that precolonial cultures were sometimes fabrications, involving the reconstruction, rather than the remembering, of a past, inventing traditions designed to mobilise energies in order to secure strategic results in the present. Pocock's observations (2001: 89) concur with Said's analysis, as Maoris pre-empt the title of tangata whenua in order to assert that 'an animist and holistic view of the universe, the land and human existence prevailed among their ancestors in Aotearoa before contact'. The construction of this discourse serves several purposes: a 'claim to occupancy of the land on the basis of whakapapa and poiesis'; it is seen as 'integral to the culture in which the Treaty is read as guaranteed to them'; and as a compensatory mechanism through which the recovery of whenua (land) and mana (prestige, authority) becomes possible.

<51> The extent to which such strategies are enduringly legitimate, however, is moot;[xxv] the bicultural campaigns of the 1990s that saw the gradual restitution of many Maori cultural traditions run the risk of freezing such history in a 'retrospective utopia' and the culture in an 'oppressive authenticity',[xxvi] with actors conditioned to perform antiquated roles in re-enactments of traditional culture, as occurs four times a day at the Auckland War Memorial Museum. [xxvii] Moreover, an Internet search of images using 'Maori culture' as a search term displays a clichéd welter of grass-skirted, poi swinging, pukana posing, nose pressing, tattooed figures, petrified in a time that precedes European contact .

<52> There are other futures available. Maori art in the emergent post-settlement phase of New Zealand history may point to a future that 'is not only postmodern and postcolonial but also post-indigenous' (McCarthy 2011: 184), such that a redefinition of what tangata whenua means becomes timely. Ngati Raukawa scholar Charles Royal's definition of tangata whenua as a term that refers 'to all who live in the post-settlement New Zealand who seek a sustainable relationship with the environment' (McCarthy 2011: 233), is a generous and flexible one. It carries the seeds of a story that may settle all who make landfall in Aotearoa New Zealand.

<53> In fulfilling its historic mission as a memory site commemorating and constructing the nation's audio-visual heritage, perhaps the Archive should hearken to the sound of this emergent multicultural, post-settlement, post-indigenous future,[xxviii] connect with it, at least as much as it embalms the past through its espousal of 'mana tuturu'. The Archive may even reconsider its varied operations, so that, as a whare pupuri taonga,[xxix] it collects and refracts the many voyaging stories of cultural encounter used to write the nation and the varied worlds (real and imagined) we uniquely inhabit and share, as migrants all (tangata waka - people of the ship - rather than tangata whenua - people of the land) to this archipelago of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean. [xxx]

<54> However generously intended, Barclay's concept of 'spiritual guardianship' can be critiqued for prolonging a false historical mythology - the timeless integrity of the Maori cosmos - the hegemony of which needs to be disputed even when such essentialist constructions of (and by) the primary migrants are unlikely to extinguish themselves in the near future. Indeed, a handsomely illustrated scholarly book, Tangata Whenua, published in 2014 and winner of the 2015 Royal Society of New Zealand Science Book Prize, manifests its solid embeddedness. Clearly, such essentializing as this provides fertile grounds for enabling and empowering many Maoris. Such discourses, however, are mutable technologies, discursive machines for reconfiguring the rationality by which an iwi (tribe), a race, a nation, reconstructs its 'memory realms'. They will mean different things at different times to different people, inflected by the dynamics of cultural change that reshape, repurpose, and refashion the narratives spun from diverse archival sources, including this one, so long as discursive jousting over disputed histories persist.

Works cited

Anderson, Atholl. 2013. "A Fragile Plenty: Pre-European Māori and the New Zealand Environment." In Making a New Land: Environmental Histories of New Zealand, edited by Eric Pawson and Tom Brooking, 35-51. Dunedin: Otago University Press.

Ballara, Angela. 1996. "Who Owns Maori Tribal Tradition?" The Journal of Pacific Studies, 20: 123-137.

---. 2001. "The Innocence of History?" In Histories, Power and Loss, edited by Andrew Sharp and Paul McHugh, 123-145. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books.

Barclay, Barry. 2005. Mana Tuturu. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

Belich, James. 1996. Making Peoples: A History of the New Zealanders from Polynesian Settlement to the End of the Nineteenth Century. Penguin.

Bennett, Tony. 1995. "Civic Laboratories." Cultural Studies, 19(5): 521-47.

Carrier, James G. 1992, "Occidentalism: The World Turned Upside-down." American Ethnologist, 19(2): 195-212.

Clifford, James. 1997. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dennis, Jonathan. 1992. "Uncovering and Releasing the Images." In Documents that Move and Speak, edited by Harold Naugier, 60-65. Munich, London, New York, Paris: K.G. Saur.

Hanson, Allan. 1989. "The Making of the Maori: Culture Invention and Its Logic." American Anthropologist, 91(4): 890-902.

Huggan, Graham. 2001. The Post-Colonial Exotic. London & New York: Routledge.

Huston, Penelope. 1994. Keepers of the Frame. London: British Film Institute.

Jameson, Frederic. 1998. The Cultures of Globalisation. Durham: Duke University Press.

McCarthy, Conal. 2011. Museums and Maori, Wellington: Te Papa Press.

Lawn, Jenny. 2006. "Creativity Inc.: Globalising the Cultural Imaginary in New Zealand." In Global Fissures, Postcolonial Fusions, edited by Clara A.B. Joseph and Janet Wilson, 225-245. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Mead, Sydney. 2003. Tikanga Maori: Living by Maori Values. Wellington: Huia.

Medina, Laurie. 2003. "Commoditizing Culture: Tourism and Maya Identity." Annals of Tourism Research, 30(2): 353-368.

Mita, Merata. 1992. "The Preserved Image Speaks Out: Objectification and Reification of Living Images in Archiving and Preservation." In Documents that Move and Speak, edited by Harold Naugier, 72-76. Munich, London, New York, Paris: K.G. Saur.

Murray, Stuart. 2008. Images of Dignity. Wellington: Huia.

Nora, Pierre. 1989. "Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire." Representations, 26 (Spring): 7-24.

---. 1996. Realms of Memory. New York: Columbia University Press.

Oliver, W.H. 2001. "The Future Behind Us." In Histories, Power and Loss, edited by Andrew Sharp and Paul McHugh, 9-30. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books.

O'Regan, Tipene. 1992. "Old Myths and New Politics." New Zealand Journal of History, 26(1): 5-27.

Pawson, Eric and Brooking, Tom. 2013. Making a New Land: Environmental Histories of New Zealand. Dunedin: Otago University Press.

Pocock, J.G.A. 1992. "Tangata Whenua and Enlightenment Anthropology." New Zealand Journal of History, 26(1): 28-53.

---. 2001. "The Uniqueness of Aotearoa." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 145(4): 482-487.

---. 2001. "The Treaty Between Histories." In Histories, Power and Loss, edited by Andrew Sharp and Paul McHugh, 75-95. Bridget William Books: Wellington.

Sahlins, Marshall. 1993. "Goodbye to Tristes Tropiques: Thenography in the Context of Modern World History." The Journal of Modern History, 65(1): 1-25.

Said, Edward. 1994. Culture and Imperialism. London: Vintage.

Salmond, Anne. 1983. "The Study of Traditional Maori Society: The State of the Art." Journal of the Polynesian Society, 92(3): 309-331.

Sharp, Andrew. 1997. Justice and the Maori. Auckland: Oxford University Press.

Shelton, Lindsay. 2005. The Selling of New Zealand Movies. Wellington: Te Awa Press.

---.2011. Interview to author, November, Wellington.

Sowry, Clive. 2009. Interview to author, March, Wellington.

Stark, Frank. 2011. Interview to author, November. Wellington.

Thomas, Nicholas. 1994. Colonialism's Culture: Anthropology, Travel and Government. Cambridge: Polity Press.

---. 1992. "The Inversion of Tradition." American Ethnologist, 19(2): 213-232.

Wedde, Ian. 2005. Making Ends Meet. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

Notes

[i] The term 'Pakeha' is a Maori one used to designate, primarily, European New Zealanders, especially those descended from the British migrants of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

[ii] Prior to the advent of the NZFC, commercial film production was largely a cottage industry, with only four feature length fiction films made between the end of WW2 and 1977. A private film production company, Pacific Films, made three of them, while a government-funded documentary production unit, the National Film Unit, made the other. After making another successful film in New Zealand, Smash Palace (1981), distributed in the USA, Donaldson made a very successful career as a director in Hollywood.

[iii] Maori are the present day descendants of the East Polynesian settlers who first colonized the archipelago of islands known today as New Zealand (circa 1300).

[iv] Oral history: Jonathan Dennis, A0565, Nga Taonga Sound and Vision (2000).

[v] In 2010, some 75 long-lost silent films held by the Archive were returned to the United States, including John Ford's Upstream (1927).

[vi] Shelton became president of the Wellington Film Society in 1970, established the Wellington Film Festival two years later, and in 1979 became the first marketing director of the NZFC. Doug Eckhoff was the last CEO of the NFU and a Film Archive board member from its founding.

[vii] QEII Arts Council (Queen Elizabeth II) is now called Creative NZ. The name change reflects an assertion of cultural independence.

[viii] Iwi: extended kinship group, tribe, nation, people - often refers to a large group of people descended from a common ancestor.

[ix] Marae: a communal or sacred place that serves religious and social purposes; often an open space in front of the wharenui (meeting house).

[x] Taonga: treasure, applied to anything considered valuable.

[xi] New Zealand Film Archive Newsletter, no. 7, December 1983.

[xii] Early McDonald films also included Te Hui Aroha Ki Turanga: Gisborne Hui Aroha (1921) andHe Pito Whakaatu i te Noho a te Māori te Tairawhiti / Scenes of Māori Life on the East Coast (1923)

[xiii] The New Zealand Film Archive/Nga Kaitiaki o nga Taonga Whitahua Newsletter/He Panui, no. 16, February 1987, p. 4.

[xiv] Benjamin, W. (1940), On the Concept of History. Accessed 8 December 2014. http://www.marxists.org

[xv] Kaitiaki: trustee, minder, guard, custodian, guardian, keeper.

[xvi] Whakapapa: genealogy, lineage, descent.

[xvii] Some 85 per cent of Maoris live in urban areas and have no real relationship with the tribe - or tribes - that they have whakapapa links to. However, tribal authorities - or neo-tribal corporations - are the primary recipients and conduits through which the extensive awards of Treaty settlement money and resources, such as lands and fisheries, flow. Such a situation 'has led to sharp disputes, both between groups proffering different whakapapa or ancestral narratives, and between those possessing whakapapa and groups of urbanized Maori who can no longer trace their whakapapa, but claim that their mana is undiminished. The larger and more dominant groups, meanwhile, have transformed themselves into corporations for the investment of their capital, so that animist debate goes on in a climate of corporate capitalism' (Pocock 2001: 486).

[xviii] See Huggan (2001) and Medina (2003).

[xix] Taonga tuku iho: treasures handed down (literal), gift of the ancestors, precious heritage (Mead 2003: 367).

[xx] While not implemented by government, the Report accurately records the globalizing zeitgeist that seeks to transform cultural institutions into economic assets.

[xxi] In 2010, the Maori economy was worth some NZ$37 billion. It is forecast to grow considerably. http://www.mbie.govt.

[xxii] Anonymous. "Maori Language Speakers, 2010, The Social Report'." Accessed 10 April 2013 http://socialreport.msd.govt.

[xxiii] Kominik, J. 'Foreword'. Annual Report, 2011-2012. Accessed 10 April 2014 http://www.ngataonga.org.nz.

[xxiv] Tangata whenua: local people, hosts, indigenous people of the land. Manuhiri: a non-Maori person, seen as a guest in the country.

[xxv] Final deeds of settlement have been signed between the Crown and almost all of the major iwi groups.

[xxvi] The expressions belong, respectively, to historian Bill Oliver and anthropologist Jeff Sissons (McCarthy 2011: 235-36).

[xxvii] Accessed 7 May 2015. https://www.aucklandmuseum.com.

[xxviii] Multiculturalism is no political panacea, either, for increasingly heterogeneous societies, as tensions (and rioting) in several European countries, including the United Kingdom, have already revealed.

[xxix] Whare pupuri taonga: museum, house containing treasures.

[xxx] To borrow J.G.A. Pocock's useful metaphor (1991: 10).

Return to Top»