Reconstruction 8.3 (2008)

Return to Contents»

"The Image-Interface": New Forms of Narrative Visualization, Space and Time in Postmodern Cinema / Chiara Armentano

Abstract: This essay argues for an analysis of the narrative models of postmodern cinema by looking at them as visualization forms re-mediated (Bolter and Grusin 1999) by new media's formal structures. Instead of being organized in a classical way through causal and temporal logics, contemporary storytelling models seem to be structured according to "casual," "catalogue" and "homogeneous" aggregative logics following the "database" and "navigable space" visual forms of new media (Manovich 2001). The conventional "narrative" paradigm (Metz 1974; Branigan 1992, Jullier 1997) in postmodern film seems to be fully "fragmented," following textual organization models similar to computer logic and aesthetics. This essay aims to classify these new models as "database forms" (aggregation of events, by "accumulation," or "catalogue"), and "navigable space forms" (aggregation of events by "loop/repetition," "hyperlinking" or the "network" of stories). They show the importance of the "space paradigm" over the "temporal" one in the postmodern film. What is fundamental now seems to be the way of "composing" the images and the storytelling with them, that is the film's "spatial dimension." For this reason, this paper defines the cinematic image (and the image tout court) in the postmodern era as "image-interface," because it behaves like the computer interface, that is as a "spatialized image," for every kind of data with which every user/spectator wants to interact. The aim of this essay is to explore and define new forms of storytelling visualization, of space and time in contemporary postmodern cinema, supporting a prolific osmosis between "film theory" and "new media theory".

I. Introduction

<1> It has been some time since when academic studies on new media have proved that the main way for media to work is to repropose contents and aesthetic forms belonging to the previous media. Notions such as the "non-transparency of the code" and of "transcoding" become essential in this debate and are directly connected to the first study about the theory and changes of mass media. Such a study led its author to the well-known slogan "medium is message."(McLuhan 1964). As Lev Manovich (2001) points out,

in cultural communication, a code is rarely simply a neutral transport mechanism; usually it affects the messages transmitted with its help. ... A code may also provide its own model of the world, its own logical system, or ideology. Most modern cultural theories rely on these notions, which together I will refer to as the "non-transparency of the code" idea (64).

Whereas the code used in communication affects the messages transmitted, providing an ideology and its own structure of belonging, the paradigm of hierarchical file system (database) provides the world is ordered according to a "logical multilevel hierarchy," and the hypertext paradigm of World Wide Web organized as "a non-hierarchical system ruled by metonymy" (Manovich 2001:65). Mass media change the real at a phenomenal, social and ideological level. While the printed word had been conveying knowledge for centuries, thus nourishing the public imagination and unconscious, cinema has significantly changed that original code, equipping it with a (mechanical) eye, with an ear (dialogues and music) and their synaesthetic reproposals.

<2> Cinema soon imposes itself as a technology and at the same time as a multi-sensorial machine able to bring forth myths and history. Yet, with the advent of new media, even cinema has changed and "re-mediated" (Bolter and Grusin 1999) [1] its structure. Such an impact has affected mainly the film storytelling, its modes of aggregation, its models of formal and aesthetic visualization and the notions of space and time, developed in a different kind of image, which turns out to be definitively manipulated in its sign and functions.

II. Re-mediated Visualizations in Contemporary Film: Database and Navigable Space

<3> While "classical cinema" used to visualize its own contents through strictly-codified narrative structures and "modern cinema" used to organize them by showing meta-referential points of view, "postmodern cinematic narrative" [2] becomes an experimental place where to confirm its "scattering" at every level of the old structure. The narrative paradigm of contemporary films shows storytelling elements aimed at full "fragmentation" (according to Jameson's theory, 1992): whereas old narrative used to organize data in space and time according to the conventional cause-effect relations [3], contemporary film often organizes its narrative structure as a set of events devoid of any logical-causal connection, following organized models close to the new media logic and aesthetics. I would like to review the narrative models of postmodern cinema by looking at them as visualization forms re-mediated by new media formal structures, such as the "database" and the "navigable space." Instead of being organized in a classical way through logical and temporal causes, they seem to be structured according to "casual," "catalogue" and "homogeneous" aggregative logics following the "database" and "navigable space" visual forms of new media.

<4> The advent of digital media has witnessed the spread of systems aimed at filing and storing data, whereas film technology had already started a media revolution leading to reconfigure "culture tout court" like a system of audio-visual data. As Manovich (2001) underlines, "mass media and data processing are complementary technologies; they appear together and develop side by side, making modern mass society possible"(23). Mass culture is therefore the result of the parallel meeting between these two technologies originating an irremediable change in the cultural system of the advanced western societies. However, the consequences of this transformation get more visible with the world-wide marketing of computers (from 1980's onwards), and are confirmed by the advent of the Internet in the following decade [4]. Since "accumulation" and "indexing" ("cataloguing") hundreds of thousands of data have become possible, that is, since the mass advent of cinema, information (image/word/sound that is to say every possible "significant"), has started "to float" through the cultural macro-system. Moreover, we must also consider that some cultural forms which have become manifest after the advent of computers (though they didn't born with it), have then been translated into old media such as cinema and television according to the "transcoding" principle [5]. The "remediation" principle (Bolter and Grusin 1999) indeed can also be applied in reverse, in other words it enables the first media to update, using new technologies and its cultural forms to their purpose.

III. Postmodern Storytelling Paradigm: Database (I)

<5> The first of the forms re-mediated by postmodern cinema is the "database": potentially contained in the film medium which created prototypes of it during the Lumière brothers' first short movies, this form was also used by multimedia computers taking on a dominant role. Now it returns from computers to culture and cinema. As Manovich (2001) writes

... a computer database becomes a new metaphor that we use to conceptualize individual and collective cultural memory, a collection of documents or objects, and other phenomena and experiences. ... In computer science, database is defined as a structured collection of data. The data stored in a database is organized for fast search and retrieval by a computer and therefore, it is anything but a simple collection of items. ... Following art historian Ervin Panofsky's analysis of linear perspective as a "symbolic form" of the modern age, we may even call database a new symbolic form of the computer age ..., a new way to structure our experience of ourselves and of the world (214,218,219).

In the early cinema, the method of attracting by "displaying" a "catalogue" (the Lumière brothers' "Views," a sequence of shots of remote locations), was the essential part of the film work [6]. This cultural form is exactly a "database," a structured collection of data organized around an identical and repetitive "centre" represented by the views themselves. "From the point of view of the spectator/user's experience, a large proportion of them are databases in a more basic sense. They appear as collections of items with which the user can carry out various operations – to view, to navigate, to search" (Manovich, 2001:219).

<6> In postmodern cinema storytelling structure, without its traditional centripetal structure tied by causal connections, often appears similar to a (1)"database," a data collection, following a double distinction of "repetition" formulas: (a)"accumulation" and (b)"catalogue" [7]. Though complying with the same paradigm, the database forms of "accumulation" and "catalogue" are based on different criteria. As Edward Branigan (1992) and Laurent Jullier (1997) point out, there are different strategies by which the spectator can combine the film projection data: at a first level, there would be "accumulation," a purely "casual" association mode. At a upper level, there would be the "catalogue," made up of a collection of data connected to the same (thematic, space, time) core. At the third level, there is "causality" represented by a set of "episodes," originated by a spectator who connects the consequences of a central situation (Branigan 1992) [8]. In postmodern cinema, the use of narrative structures based on "causal" links (and often "chronological time") as the "episodes," becomes more and more unusual. However, according to me, in some similar cases we will obtain (2)"hybrid" forms between "database" and "narrative," in the modes referred to as (a)"hierarchical," one original cause ranks first in this hierarchy followed by its consequences, and (b)"relational," wherein the prosecution of an action depends on the causal relations between the events. Eventually, there will be the case of the (3)classical "narratives", characterized by a kind of events prosecution based exclusively on causal and chronological effects. The more the generative causes will be binding to the effects in the development of the story meaning, the closer we will get to the "classical narrative model".

<7> In the first one of the "database" paradigms, that I call "accumulation," the events result from a very simple "remote cause" serving as a pretext(a), or just happen, "without any apparent motive," developing different stories linked by a metonymic bond of pure "contiguity"(b). In both cases, stories prefer to use structural "centrifugal" modes, ellipsis, pauses and digressions, in order to take away the organic idea of story "entirety" (or centre). There is plenty of examples of "accumulation-database"(a) in the American contemporary film production: movies such as The Darjeeling Limited (2007, directed by Wes Anderson), start with a simple event which causes an action, the desire to plan a journey to India, and go on with a repeated series of unconnected situations, alternating past (the father's funeral) and present events achieving the only purpose of building up different textual lines with no impact on the narrative consistency. The initial pretext becomes less and less relevant when faced with the digressions and the long pauses of the diegesis, thus proving an "aleatory condition" for the spectator, wherein a set of information with no centre cancels the traditional organic structure and makes the story a pure "divertissement". Films as Stranger Than Paradise (1984), Down by Law (1986), Broken Flowers (2005) directed by Jim Jarmusch or Brazil (1980) by Terry Gilliam, start from a weak cause used as a "pretext", such as the journey, the escape from prison, the attempt to find his ex-girlfriend and his son, or to fight an unfair government system, in order to show stories connected by "accumulation" where the only aim is the storytelling "digression".

<8> Conversely, "accumulation" paradigms of the second type(b) are well summed up by the prototypic model of Pulp Fiction (1994, directed by Quentin Tarantino), that is by those film products that erase the original cause of the events and make the story go on alternating stories of different characters, often involved just "by chance" in the diegesis. The textual film structure develops around several plot lines (different stories about different characters), not linked by any necessity bond, with the explicit view to confounding and altering its organic perception. The paradigmatic gun shot which starts the digression about the dead passenger in Pulp Fiction, succeeds in moving the unitary sense of the work further away (Jullier 1997). A useless episode in a general perspective which however proves to be a "cumulative syntagm" inside the film centripetal structure. He Died with a Felafel in His Hand (2000, directed by Richard Lowenstein) is a clear-cut example of this type: it is about a young unemployed man whose story starts and interlocks with several other stories and people, according to an undifferentiated principle of "casualty." "Sound" (that means extra-diegetic sounds, like off-screen noises and music), becomes indispensable in postmodern cinema, even within the paradigms of "cumulative" and "casual" repetition. In both films, sound becomes like a "sensory texture" necessary to cover the holes scattered throughout the main textual structure.

<9> In the second-type "database" paradigm, the "catalogue," the events follow one another displaying a "central" (a)theme or character, (b)place where all of them happen, or (c)time or chronological duration in which they take place. An essential difference, compared to the previous notion of "accumulation," is the existence of a "centre" which elicits the following events. In the first case "a," the catalogue syntagms are connected by "consecutive" elements, building stories linked by the actions of a single character or by the events about a general theme; differently, in the second and third case "b" and "c," the catalogue syntagms are "not consecutive," that is they are not correlated at all, so that they make an exact "catalogue" of data where the different plot lines are totally independent each other.

<10> The centre of the first kind of catalogue(a) is the main "character" (heroic or nostalgic), or a particular "theme" (love, friendship, suffering, speed and cars, dinosaurs, and so on). Some of these films are often built on a series of special effects perceived as "immersive experiences." Examples of this type are a wide variety of films with frequent "sensory effects" also due to the high volume of the music and the sounds: the whole series of Die Hard [9], The Fast and The Furious (2001, directed by Rob Cohen) [10], xXx (2002, by Rob Cohen), Rollerball (2001, by John McTiernan) and Jurassic Park (and its successors), based on the original matrix of Jaws (1975, directed by Steven Spielberg) [11]. These films are often realized in order to produce second episodes and sequels and whose contents remain basically unchanged, with a more and more frequent use of audio-visual effects going toward a more "hyper-sensorial" direction.

<11> In the second-type of "catalogue-database"(b), the "place" plays a key role for the information sequence. Different stories without other connections develop in the same physical space, room, apartment, car, city or whatever. Night on Earth (1991) and Mystery Train (1989), both directed by Jim Jarmusch, appear as "place catalogue" structures: in the first one the episodes take all place inside a taxi, while the second one depicts three odd stories connected to one another by the same city (Memphis). Four Rooms (1995) [12] follows the same structure but divided into four parts, alternating four different stories set in 4 rooms of the same hotel. Hotel Room (1993) [13] directed by David Lynch and James Signorelli, commissioned by the satellite network HBO, show the room 603 of an hotel where three stories take place in different periods of time. The storytelling structure is always the same, a "place catalogue" where the plot lines are normally not linked in other way except for the mentioned places.

<12> In the third-type catalogue(c), database structure alternates a series of stories happened in an identical "time" or "chronological duration" frame. Humanity's Last New Year's Eve (L'ultimo capodanno, 1998, directed by Marco Risi) is a good example of this type of catalogue: the action takes place in the same night (time) of December 31st in different flats of a residential area in Rome. Similarly, Crash (2004, directed by Paul Haggis) is about the heartbreaking stories of some people in Los Angeles, in the duration of about 36 hours (chronological duration) of the daily life in the famous Californian metropolis. Here, several car accidents provoke the only possible physical contact mentioned in the film title. The plot lines are again without causal connections, displaying the "time catalogue" as the main storytelling aggregation structure.

<13> The "database film" paradigm, considered from both the "accumulation" and "catalogue" points of view, behaves as a "objects-container" implied into the aesthetic forms of the new media. Whereas the aesthetic category of "fragment"(Calabrese 1987) would convey a semantic relevance to the object detached from the whole and reproposed in a different context, in the same way, the "database film" selects a wide amount of "fragment-objects" and reproposes them into new contexts, according to "destructured" and "a-causal" film morphologies. The principal aspect of postmodern cinematic storytelling seem to be the totally "fragmentation" of film plot.

<14> At a second level, after the database model(1), the structural storytelling form of postmodern films leaves room to a "hybrid" paradigm between the "database" itself and the "classical narrative," what I refer to as the "narrative-database"(2). This is the form of many film stories, half-way between an "a-causal structure" and the attempt to explain narrative by only one or a series of connected causes whose consequences would have visible effects on the story. In this paradigm, there would be two different levels of "narrative-database": at level(a) corresponds to the so-called "hierarchical" [14] structure, in which the "original cause" ranks first into the hierarchy. This cause would lead the action to move into a specific direction involving specific consequences. Atonement (2007, directed by Joe Wright) is an example of this hybrid type, in which the false accusation against a promising young man will spoil his own and his lover's life. This film shows the consequences of such an original cause inside a chronological-time frame. Level(b) corresponds to the so-called "relational" [15] model, whose original motive multiplies and gives life to a thick network of "relations" and consequences, whose outcomes build the film plot itself. Michael Clayton (2007, directed by Tony Gilroy) places in a similar relational structure the deeds of a lawyer who strives to disclose the corrupted strategies of a multinational company. Many postmodern films appear like "hybrid forms" between "narrative" and "database," based alternatively on the accumulation of "casual" links and on the evolution of "causal" connections, such as Cachè (2005), Funny Games (1997) both directed by Michael Haneke, where the actions are half-way between "causal link" and "pure casualty".

<15> The third paradigm is "narrative"(3), which uses a classical textual pattern mainly based on "causal-logic" links. This model will entail films coming from classical literature, theatre adaptations as well as historical biographies. William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet (1996, directed by Baz Luhrmann) is one of them. As the adaptation of the most known Shakespeare's play, excellent at transposing dialogues and developing causal and temporal events, this film is an accurate film version of the famous theatre play but with clear differences from the original one. First of all, "settings": the story is set no longer in the classical scenario of the quite Verona but in the versatile "Verona Beach," an urban area more similar to a futurist Los Angeles than to a Medieval village. Secondarily, young Romeo wears Hawaiian skirts like a Californian surfer, Mercutio wears a tight suit which he has on proudly at the party held by the Capulets family. All these details are dressed up by guns and shootings and by an accelerated rhythm of psychedelic, excessive, deafening and immersive sounds soaked in the most redundant postmodern style. As you can see, even if the plot structure follows a classical "narrative paradigm", the result of postmodern version always distorts and emphasizes the differences from the original story, producing again a "fragmentary effect" of the first storytelling prototype.

<16> From all three analyzed "visual plot organization" levels, of (1)"database," (2)"narrative-database" and (3)classical "narrative", postmodern film is always based upon a "variations of the repetition" system, devising different modes of thematic and temporal "alteration" which always produce highly "destructured systems" as to forms and contexts. For example in Atonement (narrative-database), the first sequence shows the same scene with the main character twice (going out of the fountain of her garden) according to the double point of view of different characters. Conversely, in the last sequence, we can see two different stories of the reunion of the characters. One of the stories is fictional and reflects the narrator's expectations, the other one is real and differs from the first one to the extent that the above-characters are no longer there because they are dead. Only at the end, we have a consistent idea of what really happened because of the presence of a "deus ex machina", the female-author of the biography, that discloses the narrative tricks of what she created. The result of these multifarious operations is a constant character in the aesthetic visualisation of contemporary films in the postmodern era: the repetition of "variation forms" ruled by the "difference", that does not imply any longer the need for causal relations even when there are some. What is important is they are always "fragmented" and "deconstructed".

IV. Postmodern Storytelling Paradigm: Navigable Space (II)

<17> According to what said so far, the plot structure of postmodern film would result from the following three forms of visualization: (1)"database" (as "accumulation" and "catalogue"), (2)"narrative-database" ("hierarchical" or "relational" types), and eventually (3)simple "narrative" (adaptation of stories of the past, with different levels of "variations of the repetition"). According to Manovich, the need for remediation had come up highlighting the visualisation forms which, as the "database," derived from new media, started to appear in an indefinite amount of cultural products, starting from that medium which is the closest one to computer, that is the cinema. Nevertheless, the structures of postmodern films would not consist in models similar only to the "database" forms.

<18> The second "remediated" aesthetic form used in this analysis about contemporary film texts is (4)the "navigable space" paradigm. Whereas in "database", syntagms followed one another along a linear development and asked only to be read (from a "fixed" and "contemplative" position) to the spectator (according to cases), the most important things in "navigable space" occurs no longer in terms of "contemplation" but rather in terms of "exploration". The interactive system to which responds the video-player or the virtual navigator is a good example of this new operative condition of the user of audio-visual products. Here, the purpose is no longer "displaying" stories, characters, or situations in their "causal," "temporal" or "casual" evolution: the aim is now "to create" worlds, to give life to whole universes where "to move", "interact", "navigate", "choose" a personal pathway based on one's own preferences. Hence the prerequisites for a new contact with spectators could be summed up in this simple way: I (film director/author/programmer) create a world for you (any user) enabling you to explore it and to be the one to decide what to do with, which ways to go and which ones to miss. Nonetheless, if you do not accept these conditions, the game is over, the "inter-action" is over and above all there is no meaning for this kind of game. The films that want to create "navigable universes" show a similar type of "negotiation" (Casetti 2002), with the risk to exclude from the game the player-spectator. This would seem the reason why similar products are often accused of being incomprehensible, perhaps because the starting agreement has been neglected. In other words, one refuses to play a role which is not exclusively contained between "contemplation" and "interpretation." Universes like these ones do not want to be any longer read and understood as "codes": they only need for "cybernauts".

<19> What is meant for "navigable space" is well explained by Manovich (2001):

The term cyberspace is derived from another term – cybernetics. In his 1947 book Cybernetics, mathematician Norbert Wiener defined it as "the science of control and communications in the animal and machine." Wiener conceived of cybernetics during World War II when he was working on problems concerning gunfire control and automatic missile guidance. He derived the term cybernetics from the ancient Greek word kybernetikos, which refers to the art of steersman and can be translated as "good at steering." Thus the idea of navigable space lies at the very origins of the computer era (251).

While trying to organize the substantial amount of literature which studied "navigable space" or "cyberspace" [16], the first thing to point out is its main paradox which can be summed up into the slogan: "There is no space in cyberspace" (Manovich 2001:253). The navigable space can be depicted as a system whose coordinates of digital graphics correspond to "an empty Renaissance space"(254).

<20> "Empty," "aggregate" and "haptic" space. That calls to mind the sequence of the first film of the trilogy of Matrix [17], where Morpheus explains to Neo what Matrix really is by showing him an empty and white space, subsequently filled with different objects and characters, selected and put inside it. The navigable space is exactly this and in order to be realized, it must meet some requirements:

-

"aggregation" in a double sense: (a)as "overlapping" of objects, (b)as "stratification" of different levels (aggregate space);

-

"navigability", by a simulation system (optical-haptic) enabling the user to enter it (navigable space);

-

"virtuality", meant as the union between an "isotropic" condition, that is not structurally linked to the physical reality and to the human body, not preferring any specific axis, and at the same time an "anthropological" condition which conversely prefers "horizontal" and "vertical" axis by which man acts into the space (virtual space);

-

"homogeneity", since despite deriving from an aggregation, it is nonetheless made up of objects of the same material, that is all "pixel on the level of surface; polygons or voxels, on the level of 3-D representation" (Manovich, 2001:266), (homogeneous space);

-

"subjectivity", as "its architecture responding to the subject's movement and emotion"(269), (subjective space).

<21> Each one of these characteristics falls under the form of visualisation of film texts re-mediated by the "navigable space" wherein the old narrative, as it was the case for "database", abandons the traditional causal and temporal connections in favour of a "formal aggregative structure," also referred to as navigable, virtual, homogeneous and subjective at the same time. This paradigmatic structure is characterized by an "explorative way" (exploration) followed by the user, which can be explained by three different types of textual "aggregation," obtained always by combining "consecutive syntagms" along the film structure: (1)the combination of "identical/identity" stories coming back to the starting point (that can be called "loop forms"); (2)the combination of different stories which meet at some points ("Hyperlink forms"); and in the end (3)the combination of different stories able to make remote worlds collide into space and time ("Network forms") [18]. Postmodern cinema shows these trends alternatively, according to some modes characterized often from an "interactive" and "hyper-sensorial" point of view.

<22> The first type of the "navigable space" paradigm, referred to as "loop form", includes the films which develop a textual line which suddenly stops to start again, reflecting precisely the pattern of a "loop."

Characteristically, many new media products, whether cultural objects (such as games) or software (various media players such as QuickTime Player) use loops in their design, while treating them as temporary technological limitations. I, however, want to think about them as a source of new possibilities for new media. ... all nineteenth-century pro-cinematic devices, up through Edison's Kinetscope, were based on short loops. ... Can the loop be a new narrative form appropriate for the computer age? It is relevant to recall that the loop gave birth not only to cinema but also to computer programming. Programming involves altering the linear flow of data through control structures, such as "if/then" and "repeat/while"; the loop is the most elementary of these control structures. Most computer programs are based on repetitions of a set number of steps; this repetition is controlled by the program's main loop. ... As the practise of computer programming illustrates, the loop and the sequential progression do not have to be considered mutually exclusive. A computer program progresses from start to finish by executing a series of loops (Manovich 2001:315,317).

<23> According to Manovich, both the film and the computer techniques were already based on this "loop" form: on the other hand, the two operations of repetition (loop) and sequential storytelling (narrative) do not cancel each other out. The films reproposing this model ("loop", as a kind of "navigable space" storytelling structure) depict: stories of "variations of one's own identity" which repeat into the text (type a: "identity variations," where a character splits into a series of different repetitions of him/herself); or stories of "structural variations" which repeat the same story with different outcomes (type b: "variations of identical structures"). Lost Highway (1996, directed by David Lynch) meets the "a" type loop requirements. The film opens with the scene of a man answering the intercom and hearing a voice saying: "Dick Laurant is dead," and closes with the same man speaking the same words into the same intercom. There are two "explorative" possibilities: either the character has two different identities or the film starts from the beginning showing a real version of the story and an imaginary one [19] which reflects what the main character would have done before (or after) the murder of his wife (in any case, it will be a type of "identity variation").

Much more productive is to insist on how the very circular form of narrative in Lost Highway directly renders the circularity of the psychoanalytic process. That is to say, a crucial ingredient of Lynch's universe is a phrase, a signifying chain, which resonates as a Real that insists and always returns – a kind of basic formula that suspends and cut across time: ... in Lost Highway, the phrase which is the first and the last spoken words in the film, "Dick Laurant is dead," announcing the death of the obscene paternal figure (Mr. Eddy). The entire narrative of the film takes place in the suspension of time between these two moments. At the beginning, Fred hears these words on the intercom in his house; at the end, just before running away, he himself speaks them into the intercom. We have a circular situation: first a message which is heard but not understood by the hero, then the hero himself pronounces this message. ... The temporal loop that structures Lost Highway is thus the very loop of the psychoanalytic treatment in which, after a long detour, we return to our starting point from another perspective (Žižek 2000:17–18).

<24> Slavoj Žižek confirms the "navigable" structure of Lost Highway, implicit in a large amount of other films repeating the "loop form" as their own visualisation plot system. Mulholland Drive (2001, by D. Lynch) follows exactly the same structure showing the evolution of the film text to interrupt and start again the story of the two female characters. Sliding Doors (1998, directed by Peter Howitt) follows a similar explorative line realizing the alternative model of the "variations of identical structures" (type b). The main event is focused on the underground sequence: Helen takes the train and her life changes suddenly (she discovers her boyfriend's infidelity, etc.); a "variation of an identical structure" with different outcomes: Helen misses the train, her life goes on and the turning point will occur only in the end. The simple ways used in Sliding Doors do not match with the mysterious ones used in another "loop film" such as Donnie Darko (2001, directed by Richard Kelly) which ends with the initial scene revealing the mechanism of the film that rewinds and reproduces the implicit repetition of the film recording (type b again). The first sequence of the "loop" coincides with almost all the film development, while the second one corresponds to the final segment which reveals the "repetitive logic" of its discursive structure. Twelve Monkeys (1995, by Terry Gilliam) is based on a similar process where a correspondent coming from the future to prevent humankind from catching a deadly virus, is murdered in front of himself as a young boy and experiences a visionary déjà vu which had tormented him during his whole life.

<25> The second type of visual paradigm of "navigable space" is the "hyperlink" [20], wherein different stories meet at one or more common points (usually solved in the relationships among the characters). It is a plot structure frequently recognizable in postmodern cinema which differs from the "catalogue-database" form (with a centre), thanks to the presence of precise "links" among the stories depicted. And in fact, though not showing a unique and unifying point of view, these "links" among the stories (not necessarily "causal"), lead always to a further development of the narrative till their final outcome (if there is one). The "hyperlink" structure connect always different but "consecutive" plot lines.

If the World Wide Web and the original VRML are any indications, we are not moving any closer toward systematic space; instead, we are embracing aggregate space as a new norm, both metaphorically and literally. The space of the Web, in principle, cannot be thought of as a coherent totality: It is, rather, a collection of numerous files, hyperlinked but without any overall perspective to unite them. The same holds for actual 3-D spaces on the Internet. A 3-D scene as defined by a VRML file is a list of separate objects that may exist anywhere on the Internet, each created by a different person or a different program (Manovich 2001:257).

<26> An "aggregate" space represented as "homogeneous" and through which you can skip from a story-line to another one, is a kind of structure that can be often found in several postmodern film products. Requiem for a Dream (1999, directed by Darren Aronofsky) is an excellent example of "hyperlink form" where the stories of a mother, a son, a girlfriend and their friend merge and turn over creating crossing links even if not placed into a one-dimensional perspective. These stories remain separate evolutionary lines, able at the same time to be part of a film text aimed at "homogeneity". Love's a Bitch (Amores Perros, 2000, directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu) is a film about different love stories and dogs [21], wherein each single "episode" is perfectly linked to the other one by actions, micro-events or relevant elements, never closed inside a unifying perspective, just as Code Unknown: Incomplete Tales of Several Journeys (Code inconnu–Récit incomplet de divers voyages, 2000, directed by Micheal Haneke), where we assist to the multifarious development of different suffering characters. Also 21 Grams (2003, by A. G. Iñárritu) and Magnolia (1999, by Paul Thomas Anderson) show a storytelling structure similar to the "hyperlink form" with a chain of stories intertwined by different links. "Because in new media individual media elements (images, pages of text, etc.) always retain their individual identity (the principle of modularity)" (Manovich 2001:141), it seems clear that the "hyperlink" and "network" forms show stories that, taken one by one, retain a "textual and semantic autonomy" from the rest of the film. This feature is in line with the particular way of new media of presenting the "homogeneity" of a cultural product despite the "independency" of each single element. The "textual smoothness" of these film structures would result from "visualizing the points of connection" (between "consecutive" plot lines, similar to the hyperlinks, precisely), which give to the film the impression to contain perfectly the stories connected to one another. Actually, they could be shown all alone and still have a sense. Theoretically, we are not so far away from the independence of the single segments of the "catalogue-database," but practically the difference consist of the absence of "connected points" and "consecutive plot lines" in "b" and "c" types catalogue film.

<27> The last type of visual paradigm of the "navigable space" closely connected to "hyperlink," is the "network form" which is similar to the previous one but moves away from it because of its wider range of representing the hypertextual links of the aggregate stories, producing a "net form". Following the structure of an indefinite-size "network" [22] such as the World Wide Web, some stories, far away and not able to collide in time and space, find some contact points which give life to further developments though from separate points of view. Babel (2006, directed by A. Iñárritu) develops a set of crossed episodes, "homogeneous" but "autonomous" in their perspective, which create a contact among irreparably far worlds like Morocco, the United States, Mexico and Japan, though with the manifest spatial distance. The Fountain (2006, by Darren Aronofsky) follows the same visual organization: the main characters, a man and a woman, live through different temporal dimensions to confirm the power of their love in front of the tree of love. Similarly, The Hours (2002, directed by Stephen Daldry), depicts the stories of different women keeping in touch with one another and living in times and spaces conflicting in the real life. Here the "Time" paradigm proves its uselessness: it becomes a "flat" variable depending on the space depicted in order to display a wide "network of relationships".

<28> By this classification of the re-mediated structures as "database" and "navigable space", hybrid forms as the "narrative-database" and variation forms of the classical simple "narrative", I have tried to delineate the different visual and storytelling structures of contemporary films, thus favouring the US films but also mentioning some European and particularly efficient examples. It is clear, however, that the current classification remains a regulatory analysing attempt that cannot include every contemporary postmodern film. There will be many films wherein different perspectives are mixed together, both crosswise (database/space navigable) and within the same category (for example accumulation/catalogue or loop/hyperlink) with different outcomes. Just think about any example such as Brazil by Terry Gilliam, already mentioned about "accumulation-database" type (a), which belongs to a "hyperlink" structure also, as well as Run Lola Run (Lola Rennt 1998, directed by Tom Tykwer) which, starting from a "loop" structure (the same story starts several times with different outcomes according to the main character's choices), also develops a "catalogue" element of "time duration" ("c" type).

V. The Image-Interface

<29> Many scholars have described postmodernism as a cultural change which privileged "space coordinates" exacerbated on one side by the two-dimensional flattening of mass media screens and on the other side cancelled by every possible distance [23]. At the heart of this exponential form of "enlarged and absorbing spaces" in which the remaining experiential coordinates (mainly time) collapse, there would be mainly the "mass-media image," guilty of making of reality as a "simulacrum" (Baudrillard 1981), depriving daily life of its volumes and of its three-dimension and making it equal to a series of "pseudo-events"(Boorstin 1962), according to a universal paradigm referred to as "pseudo-story." Culture, now global, would have "globalised" its own past, the old "history" which once become part of texts, hypertexts, films, televisions and networks, shows its own "variation forms" able both to change its features and to cancel even its original prototype. Whether it is "post-history" or not, the old "retrospective dimension" shows itself changed into an "accumulation" of original or not original images, aimed at cancelling that unique "aura" (Benjamin 1969) of the historical paradigm turning it into its "serialized counterpart".

In the 1980s many critics described one of the key effects of "postmodernism" as that of spatialization-privileging space over time, flattening historical time, refusing grand narratives. Computer media, which evolved during the same decade, accomplished this spatialization quite literally. It replaced sequential storage with random-access storage; hierarchical organization of information with a flattened hypertext; psychological movement of narrative in novels and cinema with physical movement through space, as witnessed by endless computer animated fly-throughs or computer games such as Myst, Doom, and countless others. In time became a flat image or a landscape, something to look at or navigate through. If there is a new rhetoric or aesthetic possible here, it may have less to do with the ordering of time by a writer or an orator, and more with spatial wandering (Manovich 2001:78).

<30> If "history" can be repeated endless times [24], it will be as much possible to alter and manipulate it, till its original and unrepeatable tracks are lost, confined only to individual memory. "Time" will turn out to be "flattened" in its global-mediatized dimension: it reappears in "synchronic", "nostalgic", "repetitive" forms always "fragmented" but never in its entirety and diachronic dimension. It is no longer the essential paradigm of the renewed historical experience of postmodernism which, once cancelled every spatial and critical distance, is now able to take form in terms of general "simultaneity." One might remark that the paradigm of "simultaneity", perhaps the main effect of time in postmodern era, shows itself as the consequence of a highly "spatial cause," as the result of a distance which cancels itself into its physical substance and into its heuristic-hermeneutic (critical) depth. The old notion of "space," wherein different kinds of interpretations developed, completely disappears, cancelling that temporal dimension which still guaranteed the right distance in order to obtain a pertaining and "deep" gaze. For this reason, scholars such as Marc Augé (1995), when defining an "anthropologie du proche" as key to contemporary world, talk about the presence of "spatial phenomena of the closeness," typically postmodern, the so-called contemporary "non-places": places where the ancient spatial coordinates loose any anthropological meaning as well as their ancient time value. The new postmodern sensitivity comes from the "excess" extended to every level: "time" and "event" excess, "spatial over-supply," floating references of collective identification to which corresponds a renewed user, also referred to as "space consumer".

<31> The system underlying the process of "spatialization" is the least common denominator of every (simultaneous)"postmodern pseudo-event", of any image or logo (both two-dimensional spaces), of each phenomenon or cultural product within the contemporary western societies. We could say that the "flat space" of the ancient mass-media image, after the main computer's advent, can also be defined as "image-interface" [25]. The computer screen represents the "interface" enabling every user to open a "spatialized passage" onto the virtual world of the network. From now on, every film, television, satellite image, according to a relevant "remediation logic" will be visualized and perceived according to the visual form and logic of an "interface." A "spatial limb" constantly connected to interact with the software, one's favourite show, film or any element possibly contained by an image. A code whose confirmation would have universal proportions able to include the generative and cognitive processes of the "culture tout court".

The term human-computer interface describes the ways in which the user interacts with a computer. HCI includes physical input and output devices such as a monitor, keyboard and mouse. It also consists of metaphors used to conceptualize the organization of computer data. ... The term HCI was coined when the computer was used primarily as a tool for work. However, during the 1990s, the identity of the computer changed. ... By the end of the decade, as Internet use became commonplace, the computer's public image was no longer solely that of a tool but also a universal media machine, which could be used not only to author, but also to store, distribute, and access all media. As distribution of all forms of culture becomes computer-based, we are increasingly "interfacing" to predominantly cultural data-texts, photographs, films, music, virtual environments. In short, we are no longer interfacing to a computer but to culture encoded in digital form. ... cinema language, which originally was an interface to narrative taking place in 3-D space, is now becoming an interface to all types of computer data and media (Manovich 2001:69-70,326).

<32> Every computer operation takes place into the "interface space." It means that the "spatialized interface" will constitute the common code to each cultural product of the "mediatized experience" [26]. It is the tip of the iceberg of a long cultural process which witnessed the gradual "flattening" of its own references and each one of its specific operations in the space of the two-dimensional image, promoting at the same time a new all-inclusive category of "spatialized image", which can be referred to as "image-interface." It is not an exclusive peculiarity of the film medium, but rather a new form concerning the "image tout court" and its different uses and implications in contemporary culture, that can be now referred to as a new "postmodern spatial culture" (according to Jameson's theory, 1992). Hence, flat hypertext and movement into the space, made possible by new media through the essential interaction of representative modes of the previous media, have gradually favoured the "spatalizing/spatialized way" of producer (broadcaster) and recipient (user/spectator) of any type of cultural message. As "computer culture gradually spatializes all representations and experiences" (Manovich 2001:80), it is important to see how cinema, its principal reference point and constant related medium [27], is as much involved in this mechanism.

VI. Spatial Visualizations. Cyber-Flâneur Gaze Vs Simulative Gaze

<33> The paradigm of space, essential into the "spatialized experience" of postmodernism, entails several definitions: it is the "empty space" of the monitor-window onto the world, the "aggregate space" that cancels the ancient physical and critical distances (subjective space), the "walkable space" introducing its cybernaut straight into the world to explore (navigable space), and in the end a space that keeps on showing itself, in spite of everything, in its whole "continuity" (homogeneous space).

<34> Cinema that even before computer had opened the two-dimensional-oriented process of the cultural experience, expresses now the relevance of the spatial values, the loss of the diachronic character of the film, in order to realise products whose space become the crucial dimension of sense and the fundamental element for any temporal link/construct. Postmodern film appears as a new visual space organization whose aggregative structure produces schematic pattern and precise axial directions for the plot lines. The image produced by postmodern cinema seems to be the result of an essential "spatial operation", similar to the "digital compositing" of new media products. The main aim of this type of operation is to constitute a "continuous" and "homogeneous" space without denying its own "aggregative substance" of independent elements. As Manovich (2001) writes,

As used in the field of new media, the term "digital compositing" has a particular and well-defined meaning. It refers to the process of combining a number of moving image sequences, and possibly stills, into a single sequence with the help of special compositing software such as After Effects (Adobe), Compositor (Alias/Wavefront), or Cineon (Kodak). ... For instance, a typical special effects shot from a Hollywood film may consist of a few hundred, or even thousands, of layers. ... Digital compositing exemplifies a more general operation of computer culture-assembling together a number of elements to create a single seamless object. Thus we can distinguish between compositing in the wider sense (the general operation) and compositing in a narrow sense (assembling movie image elements to create a photorealistic shot) (136-137,138,139).

<35> The "compositing" would be an essentially theoretical operation, both in computer and in cinema, followed only subsequently by its technical counterpart. Following Manovich's statements, two essential kinds of "compositing" in contemporary films could be defined: compositing 1, which concerns the spaces built in those films that do not use any digital or specific software but can obtain effects of "manipulated" and "continuous" space by means of camera movements (short and long shots, zooms, closes up and so on); compositing 2, which concerns instead the spaces based on the use of special effects and computerized graphics (creation of non-existent objects/bodies, impossible explosions effects and so on). In both cases, the final effect will be an "homogeneous" and "continuous" space resulting from the "aggregation" of different and/or non-existent spatial dimensions, always "manipulated":

Compositing in the 1990s supports a different aesthetic characterized by smoothness and continuity. Elements are now blended together, and boundaries erased rather than emphasized. This aesthetic of continuity can best be observed in television spots and special effects sequences of feature film that were actually put together through digital compositing (i.e., compositing in the narrow, technical sense). ... [But] The aesthetics of continuity cannot be fully deduced from compositing technology ... Digital compositing, in which different spaces are combined into a single seamless virtual space, is a good example of the alternative aesthetics of continuity; moreover, compositing in general can be understood as a counterpart to montage aesthetics (Manovich 2001:142,144).

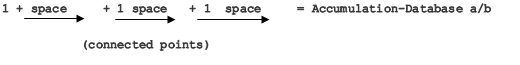

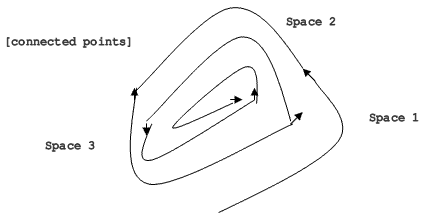

<36> The space generated by the "database" and "navigable space" films will therefore be the result of a form of "spatial aggregate compositing" whose effects are always "smooth", following on one side the rules of an "aesthetics of continuity" and on the other side the supporting axis in the postmodern production, the "aesthetics of repetition". I'm about to analyse in detail the different characteristics and organization of the "visual space" into the two main film re-mediated paradigms of postmodern cinema. In the "accumulation-database" form, the continuous spatial effect is obtained by a series of "flat spaces," associated in a contiguous way according to a linear "horizontal-oriented" path. The attempt to create the image as the homogeneous result of different flat spaces would already trace back to some film tests popular in 1960's and 1970's when the use of telephoto lens, zooms and long focal-length lenses originated the "effect-flatness" (Jullier 1997). The films that will show similar points of view would make up flat and smooth spaces without perspective, just as a "database." Moreover, in its two forms of "accumulation" ("a" and "b"), the alternation of "contiguous" spaces will visualize an explorative line developed "horizontally". The representative pattern [28] of such a type of visualization of space would reflect what follows (fig. 1):

<37> The straight lines represent the spaces alternated into the film which are built up into the diegesis – according to "accumulation" form – thus obtaining a system of consecutive spatial connection comprising some tangent points (the intersection points (+) making the story go on). Many databases structured as a "road-movie" show a similar organization pattern where open places and pleasant scenarios are shown in the "flatness" of their perspectives. The above-mentioned Searchers 2.0 directed by Alex Cox, The Darjeeling Limited by Anderson, and films such as Carrie (1976) and Sisters (1973) directed by Brian De Palma, reflect this kind of spatial visualisation. In the last ones, the use of the split-screen favours the general perception of two-dimensionality, helped by the manifest erased perspective depth. Let's just think about the Anderson's film: the spaces inside the train, the Indian external landscapes (from the desert to the village, till the meeting with the mother), and still external and internal of the return to America, all represent "flattened spaces" (also thanks to the use of zoom and long focal lenses) which follow one another in a linear way, associated by misleading tricks which however show their points of connection. It is the possibility of "convergence" between the syntagm-spaces to favour the axial "horizontal" pattern.

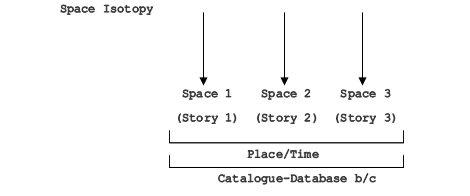

<38> In the "catalogue-database" form (types "b" and "c"), the "continuous" spatial effect is provided by a series of non-contiguous "flat spaces", connected by "parallel association" modes, along a linear "vertical-oriented" pathway. The parallel lines, corresponding to the spaces which follow one another with a (place or time) centre, will never meet anywhere (as in "accumulation"), and will run on along a "vertical" linearity. The visual pattern of the space trend in the film would be the following one (fig. 2):

<39> The straight lines represent the spaces of the film displaying a "catalogue" of "place" or "time," achieving a parallel chain (the straight lines) whose directions will never cross (because of their being non-contiguous). The pattern shows a "vertical" trend where stories not connected by any points of intersection alternate with one another but whose spaces run along the same "isotopic" axis (space isotopy) [29]. Let's take as an example Night on Earth: the spaces of the taxies running all around the city of Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Rome and Helsinki develop along a parallel linearity that never meets, in the explication of a series of elements which will compose the catalogue of independent elements, as places (or time). The similarity of the meaning (some events happened in a taxi) of each plot segment causes the "isotopy space," or the semantic homogeneity of the singular spatial figures. As the plot lines are not contiguous, but follow each other by "choice criteria", the axial pattern will be "vertical-oriented".

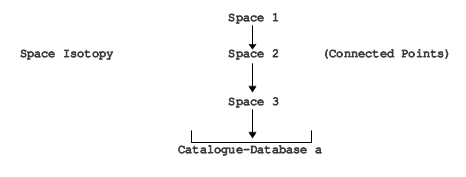

<40> The "catalogue-database" type "a", of theme/character, will show several "flat spaces" still developed along a "vertical line" but with points of contact: because of this, it will follow a "consecutive chain" similar (not identical) to that of the "accumulation". The scheme will be the following (fig. 3):

<41> Some examples of the first pattern (vertical parallel lines, fig. 2) come from films such as Night on Earth, Mystery Train and Humanity's Last New Year's Eve (catalogues "b" and "c"), where places and time alternate along spatial lines that never meet. Films such as Die Hard will serve as a valid example for the second pattern (catalogue "a," fig. 3), where the story goes on connecting tangent spaces in which the main character moves (or the theme develops). In this last case, let's take as an example Jurassic Park: the centre of the theme-catalogue is the dinosaurs' astonishment. The (isotopic) spaces which will unite, must necessarily show some contact points as the centre of the catalogue is made up of "those" particular dinosaurs (as in Die Hard the main and only well-developed character is the one roled by Bruce Willis). The closed spaces of the laboratory and the open ones of the isle are associated as a "vertical-oriented" catalogue, though no longer parallel but tangent. It is clear that there will be some cases which cannot be included into these axis. For instance, there will be films wherein the catalogue "a" of the theme is obtained through several stories put together without any connection. In that case, the "a" type catalogue will follow a spatial type "b"/"c" pattern (fig. 2). This points out once again that any regulatory attempt as the present one, is to be always downsized and placed into perspectives open to mixing and hybridization.

<42> In the "catalogue-database," the perspectives are generally "flat": the spatial audio-vision "shows off," as in a painting. For this reason, Jullier (1997) used to talk about a "voyeur" spectator: similar to an "explorer", he has to jump from a space to another one while keeping the unbiased position of someone looking at a sequence of data. This could be defined as a "cyber-flâneur". By following the well-known journey of the Baudelaire's traveller [30], this "cyber-flâneur" lets himself be carried by the flow of information, looking from outside but refusing to get in. The typical film gaze defined by Anne Friedberg (1993) as "mobilized virtual gaze," corresponds here to the "cyber-gaze" of a postmodern flaneur made mobile and virtual by the explorative camera, yet in the case of the "database", still devoid of any participatory dimension.

The virtual gaze is not a direct perception but a received perception mediated through representation. I introduce this compound term in order to describe a gaze that travels in an imaginary flânerie through an imaginary elsewhere and an imaginary elsewhen. The mobilized gaze has a history, which begins well before the cinema and is rooted in other cultural activities that involve walking and travel. The virtual gaze has a history rooted in all forms of visual representation (back to cave painting), but produced most dramatically by photography. The cinema developed as an apparatus that combined the "mobile" with the "virtual." Hence, cinematic spectatorship changed, in unprecedented ways, concepts of the present and the real (Friedberg, 1993:2-3).

The "cyber-flâneur's eye" would be much more similar to the eye of an ephemeral "explorer" who, instead of "plunging" into audio-vision, prefers to remain quietly detached, "looking" what is displayed, just as it happens in a "database".

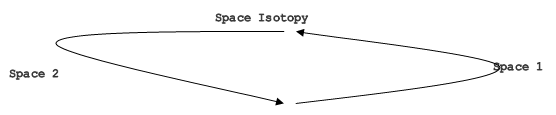

<43> In the "navigable space" form, the spatial effect appears once again aimed at the "aesthetics of continuity", though corresponding to several "deep spaces," always contiguous in their consecutive association, that constitute a "circular-oriented" explorative pathway. As the computer space, the postmodern film's navigable space is characterized by an "isotropic" condition, that is without any human vertical/horizontal axial scheme (see the point 3 explaining the characters of navigable space). Verticality and horizontality are "anthropological" conditions of the only "database", that need a kind of precise organization, otherwise it is totally ineffectual and confusing. Differently, the navigable space prefers a kind of organization oriented to "circular" or "spiral-shaped" forms, because it doesn't depend on a human organization. Consequently, the spectator will be spurred to go "into" the images, to entry those spaces no longer displaying vertical and horizontal spatial lines: this is the first reason why these kind of spaces are depicted as "deep". The depth of the space is also due to the use of some camera movements, such as travelling, louma or steadicam, as well as to the movement of the camera trying "to enter" (Jullier 1997) without apparent reasons in the story-meaning. The first aggregative mode of navigable space, the "loop," sees the spaces alternating, returning and travelling back the same "elliptic-shaped" way. The visual representative pattern would correspond to the following one (fig. 4):

<44> The two elliptic opposite lines represent the alternating spaces in the diegesis –which stops and starts again- along the same isotopic axis (as all "catalogue-databases"): the resulting system links two dimensions with "isotopic connectors" (points of contact between the two stories, usually similar meaning figures) yet not privileging any reading order, but supporting a visual space of plot development similar to the topology known as "the Möbius strip" [31]. Films such as Mulholland Drive and Sliding Doors privilege schematic models as these ones where alternating spaces depict an elliptic-shaped trajectory going back and forth thus confounding the origin and end points of the main plot line itself ("loop", types "a" and "b"). Just take Mulholland Drive: the open space of the first accident, followed by the closed ones at Bettie's house, at the diner, at Diane's flat and the confined place of the "Teatro Silencio", stops to show the isotopic spaces which, from Diane's mirror house, comes back outside at Rita's party and ends up with the suicide in the bedroom, whose outcomes had already been anticipated in the first part of the film. The visual plot organization is clearly cyclical and developed along an "ellipsis".

<45> In the remaining "navigable" forms, the "hyperlink" and the "network", the spatial effect still appears continuous and made up of "deep" and "consecutive" spaces though expressed along a "non-isotopic" axis which follows a "spiral-shaped" path. This time, the representative pattern would be the following one (fig. 5):

The alternating manipulated spaces follow here a "spiral-shaped pathway" thus generating a representative pattern wherein the dimensions are still connected in points of contacts but privilege a prosecution space closer to "labyrinth" [32] and to the so-called "rhizome" (Deleuze and Guattari 1980) [33]. The labyrinth is indeed the form, in the symbolic classical tradition, connected to "spiral" [34]. Similar examples of spatial organization can be seen in films such as Requiem for a Dream, Love's a Bitch, Magnolia and Babel, wherein the sequence of spaces shows a "spiral-shaped" prosecution marked by the tangent points of the stories: the tangled network generated by the events and characters originates a macro-system of relationships and connections whose visualisation reflects the space of the Net (the Internet). Let's consider Babel: the internal spaces of the house in America, where two children and a housekeeper live, connect continuously to their parents' external ones in Morocco, as well as to the outdoor spaces where the Moroccan family lives guilty of having injured one of them, till the hyper-technological indoor and outdoor spaces of modern Tokyo. These spatial connections follow once again a "spiral-oriented" labyrinth path.

<46> If these differing spaces of "hyperlink" and "network" structures, alternate consecutively – always showing their connection points – and run along a "spiral-shaped line" characterized by a "rhizomatic" development and effects of depth (also due to the use of travelling, and so on), it is clear that the here-assumed model of gaze will not match with the one of the "mobile observer/explorer" of the "cyber-flâneur". The message is now based on a pattern aimed at "including", "involving" and making the spectators "participate" as "insiders"—a kind of "internal gaze" suggesting that the spectator is and must feel totally involved. Hence this gaze will be referred to as "simulative".

<47> By "simulation", I mean a reproductive procedure not limited to maintain the superficial (audio-visual in this case) characteristics of the object to be reproduced but able to include its "dynamic"/"behavioural" model. "To make dynamic" means to interpret the "dynamism" (see "time" and "movement") of the object to be simulated and inscribe it into the recipient, that is to say to be able to repeat the exact operation "rules" of this dynamic object and make an individual, not involved in a direct way with it, "test" them. The first military flight simulators [35] proved the fundamental equation underlying every "simulational system": what is reproduced is not the image (icon) of a moving airplane but "the simulation of that movement," of its "rules," in other words the reproduction of a "dynamic model of the behaviour" of the airplane, which would enable the individual to control the flying means. It is no longer looking at an object by "decoding" its mechanisms, now it's time to "test" it, taking its dynamic and behavioural rules and being involved in the "real sensation" of manoeuvring and controlling the moving object. Just like in a videogame. The audio-visual effects generated thanks to digital and to the most recent softwares would produce a filmed and edited image that "is a better simulation technology than a physical construction; and a virtual image controlled by a computer is better still"(Manovich 2001:276).

<48> As it was already the case for the "database" and the "space navigable" forms, the osmosis between audio-visual reproduction and computerized technologies produced (and will still do it) a huge amount of "cultural remediation" products destined to become more and more visible within the universal media scenario. The case of the "simulation technology" proves this condition, passing from the original military uses to the industry of entertainment and to cinema itself.

<49> I would like to make clear that "navigable space films" belong to a gaze referred to as "simulative," as they are able to produce effects similar to "simulations." Thanks to the relevant use of Computer Graphics and digital effects, cinema is now able to "simulate" worlds and make the spectator equal to a "cybernaut" who can move "inside" the virtual reality of the audio-visual image. It is not at all a new frontier. Simulation has always existed, above all at several levels of "ludic forms": nonetheless, cybertexts are now able to realize the original potentials of media to reproduce multiple relational and identification networks and not just "virtual observations of dynamic changes." The present and necessary goal is now to generate the same changes by manipulating the identity of the film medium: from "representation's sign-generators" to "machines' behaviour-generators." According to Gonzalo Frasca (2003) [36]:

Simulation is not a new tool. It has always been present through such common things as toys and games but also through scientific models or cybertexts like the I-Ching. However, the potential of simulation has been somehow limited because of a technological problem: it is extremely difficult to model complex systems through cogwheels. Naturally, the invention of the computer changed this situation. In the late 1990s, Espen Aarseth revolutionized electronic text studies with the following observation: electronic texts can be better understood if they are analyzed as cybernetic systems. He created a typology of texts and showed that hypertext is just one possible dimension of these systemic texts, which he called "cybertexts." Traditionally literary theory and semiotics simply could not deal with these texts, adventure games, and textual-based multi-user environments because these works are not just made of sequences of signs but, rather, behave like machines or sign-generators. The reign of representation was academically contested, opening the path for simulation and game studies (223).

<50> I have already shown, when analysing "database" and "navigable space", that the film narrative-sequence (it means cause-effect and chronological time) constitutes a structural paradigmatic model which is dying out, as it is less and less considered by postmodern cinema storytelling. I want to argue that some postmodern films seem to follow structural models similar to simulational system. According to Frasca, "the key term here is 'behavior'"(2003:223). The reproduction of "behaviour rules" aimed at "making the model testable" becomes the essential theoretical and operating core for any simulation [37]. Cinema manages to enter this mechanism, not only with its privileged role of audio-visual machine able by itself to simulate the perceptive dimensions (eye and ear), but also setting up structures of data-aggregation which, avoiding the linear (and narrative) development and keeping in line with "hypertext" structures, supports multiple developmental systems, closer to the "sign-generator" of videogames. On one hand Torben Grodal [38] says:

Films make it possible to move freely through time and space. Films make it possible to cue and simulate an experience that is close to a first-person perception (either directly by subjective shots, POV-shots) or from positions close to the persons, contrary to the fixed and distant perspective in the theatre. The focusing and framing of persons, objects and events simulate and cue the working of our attention. ... As an audiovisual media, the dominant temporal dimension is the present tense; we directly witness the events. ... The medium more easily afford story development that focuses on a "now" with an undecided future that has to be constructed by the action of the hero. ... The linear narrative forms are different from some "paratelic" phenomena like dancing in which there is reversibility in which there is no source-path-goal-schema, and different from associative structures as found in hypertexts with dense nonlinear links (Grodal 2003:138,153).

<51> Frasca, like Grodal, considers the "non-linear associative forms" expressed in the cybertext as essential to its "simulational turning point". An important feature of this structure would seem its way to define itself as "dense aggregation". "Density" means the high amount of data stored within: when talking about cinema, it will also mean a type of "dense image" of objects, data and sensorial stimuli able to make the "perceptive effects" of audio-vision as an "immersion" (Jullier 1997), multiplying them in several directions (optic, acoustic, haptic) [39]. Massimo Maietti (2004) [40], when theorizing the presence of "hypertexts" in the narrative structures of videogames, defines one of these types as "environment hypertexts," from a semiotic point of view. In these "environment hypertexts" (videogaming), there would be some verbal and visual-graphic information blocks which, placed inside hypertextual structures and links, form an "environment," that is a space wherein data are organized in a "dense," "non-linear" and "undetermined" way. Each user's input originates different effects, while "dense" spaces and times depict an overall "environment" characterized by the notion of "hypertextual indeterminacy" according to which it is not possible to thoroughly identify all of the conditions produced by the videogame. Shifting from videogames to films, the theoretical question does not change quite a lot. I would like to assume that such "environment hypertexts" are the structural construction underlying also some postmodern films, because they are able to produce "indeterminate", "non-linear," "hypertextual networks", such as the "hyperlink" and "network" forms (which show "dense" information, overlapping and confused spaces and simultaneous times). Moreover, they originate a "simulative gaze" similar to the one used by videogames.

<52> If the starting point in the definition of "simulation" was the notion of "behaviour", the attempt to reproduce the object "dynamism" goes hand in hand with "haptics" and with the "tactile" dimension. The critical debate about the evolution of contemporary audiovisual means is still stick to the real or unreal chances to realize the conversion from "sight" to "touch". The "immersive" (Jullier 1997) effects of postmodern cinema would still be a slight confirmation of the retrieval of the "haptic dimension" by contemporary film. Haptics, the immediate touching reaction offered by interactive games, is still the only concrete dimension to divide the film reproduction (iconic-representational) from "videogame simulation" [41]. Yet, the "simulative gaze", coming from some kind of contemporary cinema, would confirm the essential analogy with interactivity [42] of "haptic media" such as videogames. In order to reproduce the behaviour of any dynamic system whose movement and interaction has to be simulated, it is important that the recipient-player identifies with his/her avatar and directs his/her movement and gaze from the first person POV. In this way, it will be possible to stimulate "tactile responses," from the activated "simulative gaze", which will control the movement of buttons, joystick, and so on (output). Let's take a scene from the above-mentioned Requiem for a Dream. While one of the characters, the protagonist's Afro-American friend, runs away to escape his torturers in search for drugs, the camera is behind his back following him snap by snap running speedy. The gaze is a "high-angle long shot", enabling the spectators to see what is happening in front of him and even what is back to him. The spectator moves alongside him, runs and vibrates "with his/her senses" together with the character: the shot is exactly identical to that "high-angle" (which could be meant, given the effects, as "semi-first-person") of a videogame [43]. Contrary to being seated in front of the computer monitor, this time we don't have a manual tool to "haptically" control the movement of one's own avatar. However, the cognitive-perceptive process underlying the path would seem to be quite identical. The haptics effects originated by the sequence are equal to the sensorial, participatory and euphoric feelings originated by any videogaming experience, and they provoke behavioural reactions wherein the user shares-takes part (feels the multisensory effects [44]) in a "semi-first person" condition, adopting the behaviour of the dynamic reference model (simulated system). These would be the characteristics and perceptive effects of the postmodern cinematic "simulative gaze".

<53> On the other hand, I want to underline that the forms of spectatorship analyzed such as the two kinds of gaze, "cyber-flâneur" and "simulative," could still appear overlapped and could mutually contaminate [45], finding connection points in the communicative tangle organized by every single film text.

VII. Temporal Visualizations in Postmodern Cinema

<54> While the "image-interface" is a typical example of "postmodern image tout court," the "image-space" represents the specific one of the film product. It is a kind of image which does not care any longer about "time" (and temporal dimension), but which is instead interested solely in conceiving "compositing strategies" of its own space and, only starting from them, it generates every following variable. The "image-space" would appear as the film result of a "digital compositing", whose purpose is to "re-compose" its own structure in the "homogeneous and continuous space" of the computer. Cinema seems to behave in the same way: just starting from its "spatial aggregation" forms, all the necessary variables for constructing the whole story meaning will be produced, i.e. the plot movement and its connected time morphologies.

In addition to montage dimensions already explored by cinema (differences in images' content, composition, and movement), we now have a new dimension –the position of images in space in relation to each other. ... The logic of replacement, characteristic of cinema, gives way to the logic of addition and coexistence. Time becomes spatialized, distributed over the surface of the screen. ...The result is a new cinema in which the diacronic dimension is no longer privileged over the syncronic dimension, time is no longer privileged over space, sequence is no longer privileged over simultaneity, montage in time is no longer privileged over montage within a shot (Manovich 2001:325,326).