Reconstruction 8.3 (2008)

Return to Contents╗

Syncretism in narrativity, visuality and tactility: a case study of information visualization concerning a news media event / Ashley Holmes

Abstract: This article re-examines the appropriateness of a conceptual framework based on the semiotic scholarship of Greimas and CourtÚs which Margaret Morse championed as being suitable for analysis of television and new media. That framework is supplemented with the suggestion that narrative, visual and tactile modes of communication involve syncretism. In a case study of information visualization examples produced for Australian news media during a mine collapse tragedy and rescue at the Beaconsfield Gold Mine in Tasmania in 2006 this idea is used to identify communicative qualities potentially inherent in traditional print and television and emergent new media visualization techniques.

Narrative and visualization in the context of news

<1> Iconic links to the actual and indexical links with the real may be readily questioned in the post-photographic era (Mitchell), but they may also be reaffirmed using arguments relating to embodied intent (Holmes). The artifacts of contemporary visual media may be synthesized using analogical and digital techniques, processed and reconstituted for semiotic purposes which are ultimately subject to ideology. Thus maintaining the veracity of news illustration remains a problematic issue both in theory and practice (Johnson-Cartee). Whilst it can be argued that veracity is not a contemporary socio-cultural, political, moral or ethical imperative - having been replaced with denial and the right not to know (Cooke), most television news editors, journalists and broadcasters maintain professional allegiance to ideals of impartiality and truth. Television news programs "are considered important for providing information and opinion forming, as well as influencing the actions of the citizens in democratic societies" (Machill et.al. 186).

<2> The narrative style of presentation of television news is largely based on a tradition of reportage. That is, it is based on direct observation, or on thorough research and documentation. According to Morse "live" media such as television news seem "more closely allied with everyday life and conversational flow" where fictions of presence play a more fundamental role, than with the "authority of print or the detached realm of film fiction" (19). Researchers who otherwise advocate a more "story-telling" approach to delivery of television news arguing that it "can help make television news easier to remember and understand" nonetheless warn against tendencies that they claim can result from increasing narrativity. These include: oversimplification (personalization and emotionalization) at the level of the individual contribution; thematic imbalance (more 'soft news' with 'a human touch' to the disadvantage of socially relevant topics); exaggeration and self-reference, and therefore displacement of other types of journalistic communication (reporting, commentary, advice, and so on, to the disadvantage of the variety necessary in a democracy - in terms of topics, forms of presentation and perspectives), (Machill et. al. 186). In the contemporary media environment digital documents of various audiovisual sensory modes and channels of delivery (for example diagrammatic, photographic, video, illustrational and so on) may be searched and sequestered instantaneously from an archive then re-edited, or produced on demand. Meaning-distorting tendencies equivalent to those attributed to "increased narrativity" by Machill et. al. may arise from indiscriminate or inappropriate visual representation practices. There are further particular risks too, such as: using emotive imagery to sway public opinion, using unrelated stock images to represent persons or events, distortion of graphical information through data selection.

<3> The role of responsible information visualization is subject to increasing complexity. The field is well served by this definition:

Information visualization is a process that transforms data, information, and knowledge into a form that relies on the human visual system to perceive its embedded information. Its goal is to enable the user/viewer to observe, understand, and make sense of the information (Gershon & Page 32).

In the context of television news the service provision requirements for information visualization may vary greatly from story to story. Examples include: provision of identifying likenesses of topical persons; graphical comparisons of quantitative data sets; and reconstructions of events. Besides the more traditional static channels such as maps and diagrams there is now more common use of 2-D and 3-D animation. In addition, there is increasingly a role for interpretive visualization that Hansen described, in a review of video artwork by Bill Viola, as imaging (actualizing) physical attributes (realities) that bear no relationship to the parameters of human perception (2004: 601).

<4> This article takes a fresh look at the relationship between narrative and visualization in the context of news media. It is divided into two parts. The first part takes the form of a review of relevant cultural studies, ontological and semiotic literature in order to provide a conceptual framework for the analytical review of visualization samples that comprises the second part. An ontological model proposed by LÚvy is used to explain how a conceptual framework expounded by Morse may be re-interpreted to account for an understanding of actuality as socially constructed reality, an understanding shared by Derrida. It is claimed that Morse's otherwise useful semiotic account of television and computing, largely based on the earlier work of Greimas and CourtÚs, conflates virtuality with actuality. This conflation did not originate from the earlier work on narrative semiotics to which she refers but possibly was influenced by a cultural hysteria about the presumed disembodying experience of cyberspace in virtual reality as popularized by fiction such as William Gibson's "Neuromancer" in the late 1980s.

<5> With respect to re-evaluating their analytical usefulness in narrative and visualization contexts, the actantial, temporal and spatial dimensions of narrativity as explained by Greimas and CourtÚs and applied to television by Morse are revisited. Then it is suggested that the generic terms narrativity and visuality are useful, and that for the purpose of this discussion of kinesthetic and interactive media these terms may meaningfully be supplemented with the term, tactility. These can be described as modalities and understood as sharing some semiotic syncretism. This is a useful concept for understanding engagement and interactivity. However it is also important to recognize the uniqueness of each modality as has been noted by commentators such as Hansen (2000, 2004) and Mitchell (1994) who argue for them to be studied on their own terms.

<6> In the decade or so since Morse's conceptual framework was published aspirations for immersive virtual reality technology have waned. Social interaction via the Internet has mushroomed and now incorporates as commonplace modes of interaction like 3-D world participation, blogging and audiovisual file sharing. Technological and media convergence continues to compound in web utilities and affordances that were previously considered discrete. Yet the conditions of formerly discrete mediums - film, television, radio, print - co-exist within the emergent digital mega-media. This dual aspect of convergence and maintenance of discrete attributes of mediums is evident in the case study section that concludes this article.

<7> The rise, climax and denouement of the Beaconsfield gold mine drama in 2006 provided an unusually extended period of focus on a news event where the outcome was not to be known for sure until two miners were safely returned to the surface 14 days after they were trapped deep underground. Until that moment all of the action concerning the miners and the details of their predicament was hidden from cameras. The constant demand for news images had to be satisfied with illustration and information visualization. A selection of image data collected from various Australian news media sources during that period is presented in the second part of this article. The images are subject to analysis and reconciliation with the earlier theoretical discourse.

Part 1: Advancing Morse's conceptual framework

Actuality and currency

<8> In the introduction to a text published in 1998 titled "Virtualities: television, media art and cyberculture" Margaret Morse proposes that virtuality is "another species of fiction" that is supported by machines, especially television and computers (10). Published in the same year as the Morse text was another specifically addressing the nature of virtuality. Authored by Pierre LÚvy it is entitled "Becoming Virtual: Reality in the Digital Age." In this text LÚvy proposes an ontology that may supplement a conceptual framework such as that purported by Morse. He expounds an ontology indicating that socially constructed reality may be more appropriately understood as 'actuality' rather than, as Morse considers, a fictionality of which virtuality is an aspect (11).

<9> LÚvy's "ontological quadrivium" model clearly distinguishes the real, the possible, the actual and the virtual. The real and the actual are both manifest in that they are "fully and firmly there." The possible and the virtual however, are both latent. The virtual exists as an agent of transformation (171-172). According to LÚvy, the virtual is "the knot of tendencies or forces that accompanies a situation, event, object, or entity, and which invokes a process of resolution: actualisation." In the broadest sense, LÚvy extends his analysis of virtuality to include social institutions which he describes (possibly after Althusser) as "coagulated virtual relations." Virtualisation is inherent in the manifestation and application of all tools and other instruments, technological and social, material and abstract. LÚvy also understands virtuality as a condition that encompasses the transformation and application of power in society in the political sense (97-109). Thus, it is misunderstanding the nature of virtuality to associate it only with the advent of contemporary and emergent technologies. This mode of existence is as ancient as the fundamentally embodied human-technology matrix.

<10> Derrida apparently arrived at a similar understanding of actuality but one that takes more account of what he theorises as a perverse effect of the virtual in the hyper-real context. Derrida says that actuality has two traits. The first is "actively produced, sifted, invested, performatively interpreted by numerous apparatuses which are factitious or artificial, hierarchising and selective, always in the service of forces and interests to which 'subjects' and agents . . . are never sensitive enough." It comes to us by way of a "fictional fashioning" and privileges national, ethnocentric and most particularly Western interests. "[T]he apparent internationalisation of the sources of information is often based on an appropriation and concentration of information and broadcast capital." With political urgency Derrida warns of the complacency and denial that may arise from being overwhelmed by this simulacrum, which he suggests might be called "the delusion of the delusion."

<11> Derrida says the second trait of actuality belongs in the realm of currency and what is actually happening. It takes in not only artificial synthesis - "synthetic image, synthetic voice, all the prosthetic supplements that can take the place of real actuality" - but also a concept of virtuality - "virtual image, virtual space, and so virtual event". The virtual can no longer be opposed to "actual [actuelle] reality" (3-6).

<12> This is where LÚvy's work is helpful. He sees no opposition, claiming: "The real, substance, the thing, subsists or resists. The possible harbors nonmanifest forms . . . hidden within, these determinations insist. The essence of the virtual . . . is as a way out, an exit: it exists. The actual, however, as a manifestation of an event, arrives, its fundamental operation is occurrence." (72)

<13> One way we can think of news is as reporting of occurrence; and news has currency. Network television time is seriously compacted. Its value is determined by an algorithm that not only entwines commercial sponsorship and cost of production but also intangible qualitative inputs. With news, temporal currency is at a premium with a few notable exceptions, for example: election campaigns, some court cases, incidents of major catastrophe, natural disaster or terrorism. The shelf life of a news story is very limited.

<14> In this high-turnover context what is the duration of a news narrative? This question surely has many answers. Within a particular news bulletin the answer may be in terms of seconds. On a given network, over a 24 hour period the story may recur - it may be repeated in its entirety; it may be retold and/or updated. The story may be subject to further analysis in extended news or current affairs programs. While it is still newsworthy a story is emergent. While a story is emergent it is alive. This may be captured and delivered in constant real time; in episodes as new information comes to hand; as a summary account or an update; or maybe even as a footnote. There is a hierarchy of implicit value whereby stories and images command and lose their value based on currency, also known as topicality, relevance or actualitÚ – "with a decidedly temporal emphasis" (Bajorek, in Derrida & Stiegler 162).

Actantial, temporal and spatial dimensions of narrativity

<15> Virtuality may be thought of as a 'seed' perpetuating the actualization of the function of any action, tool, instrument or institution. Both virtuality and actuality are aspects of corporeal experience. Experience, whether real or imagined may be expressed, mediated and remediated as stories and pictures that evoke sensations in traditional analogical or digital modalities without having to resort to 'sci-fi' notions of cyberspace and virtual reality.

<16> Morse uses the theory of enunciation (11-12) to argue that television is less interactive than computer mediation, saying:

Television has yet to master a full complement of pronouns in relation to the viewer: it is versed in addressing the viewer with we and you, and it is good at the present subjunctive mode of a fiction shared present (4).

She says "it is left to the genres of cyberculture to develop the impression of . . . the interactive user as an I or a player in discursive space and time" (4).

<17> Looking to the source of Morse's useful conceptual framework, Greimas and CourtÚs explain the semiotic theory of enunciation holds that engagement and disengagement (each defined by the absence of the other) are co-existing aspects of three existential dimensions of narrative: actantial, temporal and spatial (87-90). Morse outlined the narrative problem of simulacra of the second or third degree relating to "I" or "you"; "author" or "reader" named in an utterance and how this ambiguity becomes analytically difficult in relation to the authoritative voice of television news (11-13). Greimas and CourtÚs make two further distinctions with respect to actantial (dis)engagement that may be useful in this analysis of visualization in the news media including the web: the pragmatic and the cognitive dimensions (89). The pragmatic dimension serves as an "internal referent" for the cognitive dimension and takes account of somatic (phenomenological, verbal and non-verbal) signs (241, 304). The cognitive dimension refers to "various forms of articulation of knowing - production, manipulation, organization, reception, assumption, etc" (32). These are often 'institutionalized', for example in terms of: interpretive discourses – for example arts criticism; persuasive discourses – for example politics or advertising; scientific discourses - which the authors note may play on interpretive and persuasive discourse in support of the objective which is to be "knowing-to-be-true as the project and object of value aimed for" (34).

<18> The temporal dimension incorporates the now and the not-now from the point of view of the moment of communication. It both institutionalizes that moment and from there constructs time in both past and anticipated directions (89-90). In addition, there is within the temporal a hierarchy of reference systems relating to what can be known, with now maintaining always the benefit of hindsight over the past but subject always to interpretative constructs. The now dimension has degrees of currency, somewhat similar to the currency of news as already discussed.

<19> At its most basic level spatial distinction is a function of situation as either here or elsewhere. Greimas and CourtÚs acknowledge the lack of theorization regarding the spatial dimension (90). In phenomenological theory one's ability to move through the spatial world and negotiate its obstacles is a fundamental corporeal experience and yet attempts to represent motility are chronically subject to cultural determined norms. Contemporary Western digital game culture is currently rather preoccupied with the reconciliation of digitally calculated Cartesian three-dimensionality with renaissance perspective represented on a screen plane. Panofsky has shown that perspective is a symbolic system and that clearly other visual systems satisfy spatial representational objectives in their contexts.

<20> It is appropriate to ask whether these structures may be applied to analysis of visual communication or interactivity? Is a theory of narrative discourse subject to a pervading "logic of textuality" which Hansen calls technesis? Hansen claims to have identified a persistent epistemological astigmatism that privileges discursivity at the expense of "a process of embodied reception - of reception as embodiment" that would otherwise culminate "in a nonrepresentational experience of embodied physiological sensation" (2000 261). Framing text itself as a foundational technology he says:

Not unlike the process of naturalization analyzed by Barthes (1972) in his study of myth, technesis works by proffering a discursive model of technology as a ground-zero, default model. It is therefore a construction, but one that is not so much chosen by the critic as imposed by the critical method or, more exactly, by the ideology of textualism (91).

Perhaps spatial experience may be better accounted for visually, and as Hansen suggests, non-representationally as tactility or motility. How then might this be reconciled with narrative theory?

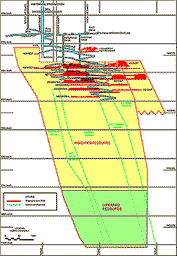

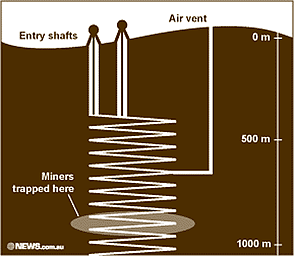

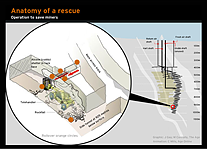

<21> Greimas and CourtÚs refer to a "generalized narrativity, freed from the restrictive meanings that linked it with the figurative forms of narratives" and which they considered to be "the organizing principle of all discourse" (210). For the purpose of better understanding the relationship between narration and visualization it is proposed here that narrativity has a semi-inscriptional, non-verbal correspondent - visuality, and a corporeal non-representational analogue - tactility. These further distinctions are especially significant with respect to information visualization in interactive media where narrative, visual and tactile modalities may constitute a mediated experience. These generic terms refer to the capacity of a narrative, a visual image or a tactile sensation to receive meaningful interpretation.

Narrativity

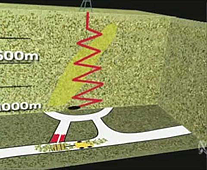

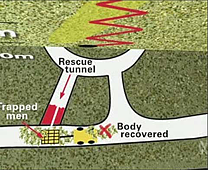

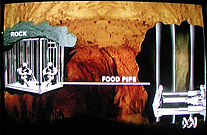

<22> Morse stresses the "liveness" of TV, radio and telephone in contrast to print and cinema, pointing out that the news "becomes the immediate or apparent cause rather than the report of events" (15). She notes how the electronic news media foster their own version of "the enunciative fallacy" (Greimas & CourtÚs: 87-90; 100-102). "Even the body we see in physical space, lips moving, voice sounding, belongs to another order of reality than the subject, 'I' in the linguistic utterance… a narrative may disengage a second-order narrative, and then install a third-order dialogue and so on" (Morse 10-12). Thus with TV news there is a potential conflation of a viewer's awareness of the narrator and the narration. It is contended here that what transpires is a state of narrativity to which a viewer is, as Benjamin so eloquently put it, "inattentively attentive" (cited in Audet et.al. 50). This generic state matches a definition by Greimas and CourtÚs of "generalized narrativity, freed from the restrictive meanings that linked it with the figurative forms of narratives" and which they considered to be "the organizing principle of all discourse" (210). Further, it is contended that narrativity has phenomenal, semiotic, cognitive and affective equivalents - visuality and tactility - that whilst being discrete modalities these may also synesthetically share some meaning-making functions.

Visuality

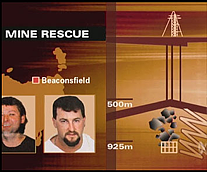

<23> Just as with narrativity, with visuality there is an analytical and critical tradition - Panofsky, Barthes, Mitchell-WJT and Mitchell-William J, being among memorable contributors.

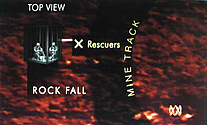

<24> It was Panofsky who infamously questioned why linear perspective should be considered the most realistic form of drawing with which to represent the world when it is one among many human symbolic systems.

Perspective subjects the artistic phenomenon to stable and even mathematically exact rules, but on the other hand, makes that phenomenon contingent upon human beings, indeed upon the individual: for these rules refer to the psychological and physical conditions of the visual impression, and the way they take effect is determined by the freely chosen position of a subjective point of view" (67).

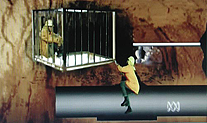

Writing about immersive virtual reality (VR) as a component of our experience of new media, Lister et. al. note how the "character of perspectival representation" is embodied in modern technological media. They extrapolate Panofsky's argument to suggest that we might think of perspective not only as a means of expression and a way of "adding meaning to what is represented" but also as a "technology for constructing the space in an image" (129).

<25> Barthes' contribution to our understanding of signs and visual semiotics though substantial and widely celebrated has more recently been re-evaluated as somewhat prejudiced by his literary background (Hansen 2000). There are calls by W. T. J. Mitchell and others for a new methodology for the study of visual culture whereby images are analyzed on their own terms. Mitchell advocates that this should not be a "return to naive mimesis" nor to "copy or correspondence theories of representation." Rather, he says it is "a postlinguistic, postsemiotic rediscovery of picture as a complex interplay between visuality, apparatus, institutions, discourse, bodies, and figurality" (1994 16).

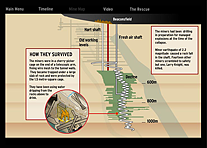

Tactility

<26> A decade on from Morse's analysis of virtuality in cyberculture as "another species of fiction" there is emergent a view of technologically prosthetic observation and of instrumental interrogation of the real world - that these are essentially extensions of the embodied phenomenological experience. As Hanson says, "Embodiment, in short, constitutes our practical means of interaction with the material flux and with the material reality of technology beyond the theatre of representation" (41). This idea counters the notion that working with computers and other technological prosthetics is somehow de-humanizing or disembodying - a concept that became prevalent in the late 1980s.

<27> The relationship of the tactile to the narrative and visual dimensions through corporeal experience is well expressed by Hansen who says, "information always requires a frame (or, alternatively, that framing is essential in the creation of information) and that this framing function is ultimately correlated with the meaning-constituting and actualizing capacity of (human) embodiment" (2002 89).

<28> Not to be confused with his afore-mentioned namesake, William J Mitchell explained how in the postphotographic era, instrumentally gained data may be digitally correlated to yield visual actualizations of the ineffable and the invisible (1992). The instrumental may be resolved as a corporeal axiom when we consider that the body engages with technology's materiality at a prediscursive, presemiotic and fundamentally tactile level of unmediated physicality (Hansen, 2000).

Syncretism

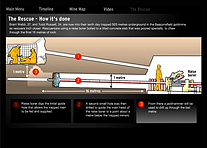

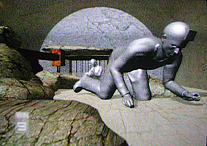

<29> Recent scientific research has borne out claims of phenomenologists such as Merleau-Ponty that the senses we conceptualise as individual and separate in fact to some degree overlap or are transposable in terms of perceptual experience. Celebrated for his role in the development of the bionic ear, Graham Clark recently claimed that people may not only hear through the skin but also may be taught to interpret visual response via tactile stimuli:

The idea of hearing through the skin is the result of an amazing ability of the brain to convert stimuli from one sense to the other. For example, a visual image has been represented as patterns of tactile stimulation on the skin of a subject's back. After training, the blindfolded volunteers learn to experience the image from the video camera on the back as the scene in front of them. The conscious experience can become so real, that when the camera is zoomed in, the person ducks, thinking the image is coming towards them.

<30> Semiotic theory has a term that refers to a relation between heterogeneous terms or categories, "encompassing them with the help of a semiotic (or linguistic) entity that brings them together": syncretism. Greimas and CourtÚs consider that in the broader sense "different semiotic systems - such as opera or cinema - will be considered syncretic when they implement several manifestation languages" (326). It is quite reasonable then to propose here that there may be syncretism between the three modalities: narrativity, visuality and tactility.

<31> Whilst there is insufficient means in an article such as this to develop in-depth commentary on these three themes or to fully define the particular qualities of each modality, the suggestion here is that semiotic theoretical discourse may be revisited in the light of Hansen's "technesis" critique (2000) so that we may better understand how the whole array of sensual knowing contributes to perception, cognition, meaning generation, identity and intent.

<32> In the case study that follows forming the second part of this article samples of information visualization from Australian news distributed via print, web and television media will be used for analysis partly according to the conceptual framework outlined above.

Part 2: Case Study

Television news information visualization of a mine tragedy and during a temporally sustained rescue operation

<33> On April 25, 2006 at 9.26 pm local time a rock fall in the Beaconsfield Mine, Tasmania, Australia, left three of the 17 miners working underground at the time trapped. From that time until the successful rescue of two of those men on May 9, 2006 at 5.58 am - some 14 days - a major news story arrested the attention of national news journalists, producers and audiences – and increasingly, ongoing throughout that time-span and beyond into the limited aftermath of celebrity for the survivors, the attention of key players in the global news and infotainment industry.

Situational overview

<34> The first task of the information visualization specialists was to create a sense of scale so that viewers could relate to the immediate predicament of the trapped miners. The News artist would have relied on extant diagrams and charts readily available from the gold mining company's corporate web site (such as Fig 1) and would have needed to simplify the data to explain just where the trapped miners were situated. The difficulty involved in understanding the scale of the vertical depth - nearly a kilometer, or over half a mile - underground was compounded by the need to express how access would normally be gained to that position. The schematic diagram at Fig 2 conveys the salient fact that the disaster site is very deep underground but relative spatial positions of structures are not realistic or to scale. In the traditional print environment there are conventions to call upon in the simplification process. Three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates may be compressed and distorted; real (sub)terranean details of position and scale may be stylized for the purpose of schematization. This is a visualization technique we are well accustomed to from urban transport maps (Spence, 2001: 2). Fundamentally stylized representations of the mine setup like this are used across all media: print, web and television.

<35> Fig 1 is an example of visual communication using the cognitive aspect of the actantial dimension of semiotic analysis. It is being used to represent what the mining company claims is known-to-be-true for the information of investors (Greimas and CourtÚs: 34). Whereas Fig 2 takes more account of the pragmatic aspect of the actantial dimension (242, 304). Even though it is essentially misrepresenting reality by transposing the information in a way that essentially distorts, the information is acceptable to the viewer because the translation is a simplification and conversion into signs quickly readable at human scale. The distortion is acceptable in context. People can relate to the image at Fig 2 through its qualities of narrativity, visuality and its tactility. The tactile quality readily accounts for spatial aspects that linguistic semiotics labors to come to terms with.

Fig 1. Source: http://www.beaconsfieldgold.com.au/BMJV.html

(Click image for larger version.)

A geological section indicating historical and current development of the stoping at Beaconsfield

Fig 2. Source:

http://www.news.com.au

(Click image for larger version.)

A 2D line and tone graphic devised for print news.

<36> Two days after news of the rockfall incident broke, tragedy became apparent with the discovery of the body of one miner. The first of what would become a number of three-dimensional, time-based versions portraying the scenario was released on ABC TV News (Figs 3a, 3b). It utilized a simple 3-D cubic primitive model with textures and graphics applied to the faces of the primitive. In the context of national television news it provided a kinesthetic visual which accompanied narration explaining the trapped miners' predicament and the difficulty of a rescue mission. More information was introduced about the layout of the rescue zone, including the site where the deceased miner was found. Note how the schematic of the mine access indicated by the red zig-zagging line has been simplified even more from the rendition at Fig 2. The diagram on the base plane provided a map of the recovery and rescue sites. An animated sequence was affected by zooming and tilting a virtual camera from a wider view horizontal to a closer vertical view of the model.

<37> Arguably the information in this segment is no more effectively conveyed than in the 2-D graphic at Fig 2. The 3-D primitive technique employed here doesn't significantly aid a viewer's understanding of the miners' situation except for the incorporation of the map view. It may however have served the purpose of providing a more dynamic visual that lasted for the duration of the journalist's voiced report. Additionally the incorporation of the z-axis or depth dimension expresses, not as Morse would have it, "a virtual relation to 'you'", but rather enhances the viewer's corporeal sense of motitilty and provides an experience of scale and terrestrial depth that one may relate to through syncretic integration of narrativity visuality and tactility. Though not particularly engaging in this instance it is experienced as actuality rather than virtuality.

Fig 3a. Source: ABC

TV News

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig 3b. Source: ABC

TV News

(Click image for larger version.)

Stills from an animated TV news visualization constructed using 3-dimensional computer graphic primitives with bitmap images applied to the surfaces. A virtual camera zoomed and tilted over the model to record the animation.

Supporting graphics

<38> Graphics supporting a TV news story (for example Fig 4) will often appear on a screen behind or beside the presenter. If such graphics occupy the whole view it is likely to be momentarily. Occasionally such images are used as a visual filler where there is no other visual to support an audio report. The visual is usually static. It will serve to contextualize the whole audiovisual news presentation, and may involve the news anchor, onsite presenters, interviews and live footage. Graphics for this purpose need to be bold and simple. They often exhibit illustrative techniques to homogenize heterogeneous elements incorporating a variety of visual channels and textual elements. For this reason such visuals may make good examples of narrative/visual syncretism. Notice once again the zig-zag. It has become almost a symbol. The image of the mine head too is gaining this status. There is a grid shape featured. It has been revealed that the trapped miners are in a safety cage. This was depicted also in Fig 3. The safety cage grid will become a symbol too in graphics of this type. Snapshot photos of the two men have been illustratively treated to match the overall color scheme and rendering but maintain their authenticity as personal snaps. They may have been retouched but they have not been re-drafted from scratch as portraits. The overall composition combines a headline, a location map, retouched photo images of the trapped men and a schematic section of the mine and the accident site.

Fig 4.

Source: ABC TV News

(Click image for larger version.)

Supporting graphics from ABC TV News.

An emerging narrative

<39> By April 29 the pair of miners remaining missing had been confirmed as surviving in a telehandler cage. However it had been deemed that they were not safely accessible via the route where the collapse had occurred. This is a matter of controversy in more detailed narrative analysis. A rescue worker claimed to have made verbal contact with the trapped men by picking his way through the rubble via that route. A lateral drilling operation through solid rock was instigated in order to establish safe communication, supply of emergency rations and comforts. An early version of an ABC TV News graphic at Fig 5 shows a combination of plan view of the mine tunnels and profile (perspective) view of the miners in the cage. The visualizer has labeled the illustration "Top View." However this label does not fit with the view of the miners and creates ambiguity.

Fig

5. Source:

ABC TV News

(Click image for larger version.)

An early version of an ABC TV News graphic.

<40> Rescue plans emerged over days. After a small-diameter pilot hole was successfully drilled and essential supplies delivered to the miners machining of a rescue tunnel began. This kept the currency of the story alive for a prolonged period. As a result resources not commonly allocated for stories of lesser duration of currency began to be afforded for visualization of the story in a number of major news departments. Figs 6a-c show versions of an emergent graphic illustrating rescue plans as they were progressively revised.

Fig 6a. Source: ABC

TV News

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig 6b. Source: ABC

TV News

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig 6c. Source: ABC

TV News

(Click image for larger version.)

This static image from ABC TV News evolved over time as the rescue plans progressed.

<41> Progress in drilling the horizontal rescue shaft was slow due to the extreme hardness of the rock. Anticipation of the safe release of the men built up daily. A huge contingent of press from all over the world had formed a makeshift camp at the mine site, eagerly awaiting developments. Figs 7a-b show two sequential stills used to illustrate an ABC TV News report describing how rescuers planned to release the trapped miners. The second image shows one of the miners escaping from the cage.

Fig 7a. Source: ABC TV News

Fig 7b. Source: ABC TV News

A sequence of images from ABC TV News is used to convey an escape plan.

Interactive media

<42> The Age newspaper web site featured an interactive version of a graphic designed also for print (see Figs 8a-b). An online user rolls over bullet points in the graphic to reveal textual explanations. The abstracted qualities topical in this paper - narrativity, visuality and tactility - are components contributing to mediated experiences of engagement, immersion and flow. Whilst these experiences are affected or arise out of richness of media experience they do not in themselves constitute interactivity. Indeed, in the context of television news as we know it today, interactivity is not a significant feature. The 'interactive' web graphic shown a Fig 8a, with a detail of the text box that appears on-rollover of an orange dot at Fig 8b, is not a particularly engaging example of interactivity either.

Fig 8a. Source:

http://www.theage.com.au

(Click image for larger version.)

The online version of a print graphic.

Fig 8b. Source:

http://www.theage.com.au

(Click image for larger version.)

Textual explanations appear 'on mouseover' of bullet points.

<43> On the culmination of the rescue The Age published an interactive timeline as part of its online coverage. Figs 8a-e show how in some interactive media artifacts, subject, space and time need not be a unified or coherent whole. "They can be simulated independently and are capable of being disengaged or engaged separately" (Morse 12). This web feature incorporated an interactive timeline of events (Fig 9b), a page called a "Mine Map" but which is really a sectional view (Fig 9c), a selection of video and audio casts (Fig 9d), and an interactive schematic diagram telling the story of the rescue with rollover captions (Fig 9e). Because this site provides the choice of a number of ways of looking at the event it is much more meaningfully interactive in the sense that the user can choose from more narrative, more visual and more kinesthetic options. As a whole the site communicates through the actantial, the temporal and the spatial semiotic dimensions. It could only have been produced with this level of features in retrospect – that is, after the event, and so it has a kind of celebratory souvenir quality.

Fig 9a. Source:

http://www.theage.com.au

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig

9b. Source:

http://www.theage.com.au

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig

9c. Source:

http://www.theage.com.au

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig

9d. Source:

http://www.theage.com.au

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig

9e. Source:

http://www.theage.com.au

(Click image for larger version.)

Incorporated into this Flash™-based info-graphic were diarized textual narratives, photo highlights, maps and information visualizations, plus audio and video grabs from radio and television media.

Parallel visual documentation across the news media

<44> Compared to the television news graphics, the print and web graphics contain more detail and textural information. They arguably contain more visual information relevant to conveying greater understanding of actuality of the situation. For instance, Figs 10 a-b show a more convincing scale difference between men and machinery and portray a much more accurate view of the scale of the cage the miners were trapped in than those images at Figs 6-8. Press graphics may be monotone or color.

Fig 10a. Source:

The

Australian

(Click image for larger version.)

Newspaper graphic.

Fig 10b. Source: The

Australian

(Click image for larger version.)

Newspaper graphic.

<45> The television visualizations such as those at Fig 7 tend to sequentially show more than one static view or to be simply animated. However such images usually appear for no more than a second or two and so must quickly perform their function. The function is to support the narration, providing schematic spatial information that cannot be easily conveyed using live video images or verbal descriptions.

<46> An unusual twist of the typical television news visualization scenario occurred when the late Richard Carleton, in what turned out to be his last on-location current affairs report for Channel Nine's 60 Minutes, used a graphic from The Age newspaper to illustrate an assertion he was making. He held the paper in his hand (Fig 11a) and whilst the camera zoomed in on the graphic he used a pen to demonstrate his narrative, gesturing emphatically in real-time (Fig 11b). This is a significant and sophisticated example inter-media narration and visualization and demonstrates how the syncretic qualities of narrativity, visuality and tactility can work effectively together in a television segment produced to affect viewers with a sense of liveness and currency. [1]

Fig 11a. Source: http://ninemsn.video.msn.com/v/en-au/v.htm?t=m163

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig 11b. Source: http://ninemsn.video.msn.com/v/en-au/v.htm?t=m163

(Click image for larger version.)

These stills from a 60 Minutes current affairs program called "Beaconsfield's chequered past" and featuring the late Richard Carleton were captured from a ninemsn videostream.

3-D modeled graphics

<47> Channel Nine also featured a series of animated 3-D modeled graphics of the scenario. The sophistication of the modeling and rendering increased as time went by. Though the images at Fig 12 a-b were obviously devised as an animation, only selected stills accompanied the narration. The model of the raise borer in Fig 12 looks like it may be a re-purposed model of a military vehicle.

Fig 12a. Source: National Nine News

Fig 12b. Source: National Nine News

Early versions of a 3-D model of the rescue site by screened by National Nine News.

<48> A short 3-D animated sequence was aired on National Nine News as the drama was drawing to a close and the rescue of the miners was imminent (Figs 13 a-d). At first it showed the planned final stages of the rescue, and then subsequently demonstrated how that part of the rescue was performed. The sequences were also available as a streaming DV from the ninemsm website. One may well ask whether the use of the semi-immersive, '3-D world', animated model (as in Figs 13 a-d) conveys essential information as effectively as the more traditional style of diagram and schematic? Perhaps the 3-D animation provides a more experiential view that is quite different in intent and affect to the other more traditional communicative channels? Certainly the sense of movement of camera and motility of characters introduces a syncretic mix of narrativity, visuality and tactility that is new to Australian television news.

Fig 13a. Source:

National Nine News

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig 13b. Source:

National Nine News

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig 13c. Source:

National Nine News

(Click image for larger version.)

Fig 13d. Source:

National Nine News

(Click image for larger version.)

Stills from a 3-D animated sequence shown on Nine National News and available as a DV stream from the ninemsm website.

Some considerations and questions arising

<49> When compared to the other elements in the extensive and prolonged media coverage of this event, which involved an extreme level of competition especially amongst the major television news and current affairs personalities and their producers for the attention of viewers, the television news information graphics were delegated a low profile. 'Information graphics' is meant not so much to refer to the illustrated headline banners that are often displayed on screens behind the television news presenters (as in Fig 14) but those visuals which will often fill the screen and bear the responsibility for distilling quite complex concepts and processes and conveying the salient details for the better understanding of a lay public. Despite their low profile these information visualizations perform an invaluable role.

Fig 14. Source:

ABC TV News

(Click image for larger version.)

In this case study a distinction has been made between information graphics and headline illustrations of the type shown here.

<50> It is rare for a media event to be as protracted in its resolution as the Beaconsfield mine disaster and rescue. The details concerning the rescue changed from day to day. In retrospectively studying the graphics used to explain the details of the rescue it is possible to review the accuracy and veracity of the representations and ask some pertinent questions. How important was it to show where the rescue tunnel was really going to emerge in relation to the trapped men? Was an accurate representation of the scale of the trapped men in relation to their cage important? Was the difficulty of the drilling operation effectively portrayed? Were the complicating safety issues for all concerned successfully conveyed?

<51> The extended period of focus that this event provided has enabled greater opportunity than is usual for variations of concept, style and technique and for the different qualities of various graphic media modalities to be compared. Witness traditional newspaper graphics (Figs 2; 10a-b) and their hybridization into hyperimage as some newspapers also apply the graphics with interactivity online (for example Figs 8 a-b; 9 a-e). Is the requirement for multi-purpose graphics influencing the conceptual approach, illustrative style and technique? We see single-image, sequential still-image narratives, and animated sequences in both 2-D and 3-D representational formats. Is one format more effective than another in a given context? Do they serve quite separate purposes?

Conclusion

<52> Notwithstanding a necessary destygmatization of the meaning of the term 'virtuality' in order to place it in an existential ontology rather than being associated with 'cyberspace' as such, this article has re-affirmed the usefulness of Morse's 1998 conceptual framework for understanding semiotics in contemporary print, television and interactive digital media with respect to both the historically discrete and to the emerging convergent and hybrid media forms. In reviewing the literary source for Morse's framework an earlier work of Greimas and CourtÚs which had helped to define the semiotic scholarly tradition has been shown to provide a basis for considering that the visual and the tactile, as separate modalities, are also intrinsically related to the narrative modality through corporeal phenomenal experience. Those authors' analysis of the narrative modality's actantial, temporal and spatial dimensions was used to support the argument made in this article for the generic experiential and communicative modalities: narrativity, visuality and tactility, to be considered not only in their own right but also as synesthetically - or to use Greimas and CourtÚs' term, "syncretically" - contributing to what we understand as corporeal experience and to the mediation of that experience, especially in information visualization.

<53> Following Hansen, Mitchell (WTJ) and others, a claim was made that semiotic analysis has largely been 'hijacked' by discourse that privileges textual analysis at the expense of non-verbal modes of experience.

<54> With reference to a variety of images produced for Australian news media organizations during the Beaconsfield Mine tragedy and rescue it was shown that understanding the syncretic character of the narrative, visual and tactile modes is conceptually useful in semiotic analysis of information visualization. The case study focused on the potentially advantageous communicative qualities inherent in the discreet media, for example detail and spatial representation in print, interactive engagement with the web, and temporal, kinesthetic experience with television. A key finding of this study was that 2-D and 3-D representations serve distinct visual and narrative purposes. A 2-D schematic of the mineshaft may give an impression of the trapped miners' predicament deep underground whereas a 3-D animation may provide a more experiential view through a combination of perspective, virtual camera movement and character animation. Thus, in reporting news the selection of visual representations is a critical element of communicative intent and affect.

Works Cited

Audet, RenÚ et. al. Narrativity: how visual arts, cinema and literature are telling the world today. Trans. Buck, Paul and Petit, Catherine, DIS VOIR, 2007.

Clarke, Graham. "Brain Plasticity Gives Hope to Children", Lecture 5 in Restoring the Senses, 2007 Boyer Lectures: ABC Radio National, 9 December, 2007: 22 March 2008 <http://www.abc.net.au/rn/boyerlectures/stories/2007/2084251.htm>.

Cooke, Grayson. "Let's We Forget: Responsibility and the Archive under Howard" in Procedings: The UnAustralia Papers, Cultural Studies Association of Australasia, 2006: 28 November 2007 <http://www.unaustralia.com/proceedings.php>.

Derrida, Jacques and Stiegler, Bernard. Echographies of Television: filmed interviews, Trans. Bajorek, Jennifer, Polity Press, 2002.

Gershon, Nahum and Page, Ward. "What Storytelling Can Do for Information Visualization", in Communications of the ACM, Volume 44, Issue 8, 31-37, Aug. 2001.

Greimas, Algiris Julien and CourtÚs, J. Semiotics and Language: an analytical dictionary. 1972, Trans. Crist, Larry, et. al., Indiana University Press, 1982.

Hansen, Mark. Embodying technesis: technology beyond writing. University of Michigan, 2000.

Hansen, Mark. "Time of Affect, or Bearing Witness to Life" in Critical Inquiry: Spring 2004: 30, 3; Academic Research Library, pp: 584 – 686.

Holmes, Ashley. "Embodiment: Computer Networks and Symbiosis Revisited" in Proceedings of the Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education, ED-MEDIA 2003.

Johnson-Cartee, Karen S. News Narratives and News Framing: Constructing Political Reality. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2005.

LÚvy, Pierre. Becoming Virtual- reality in the digital age. Trans. Bononno, R., Plenum Press, 1998.

Lister, Martin, et.al. New Media: a critical introduction. Routledge London, New York, 2003.

Machill, Marcel, et. al. "The Use of Narrative Structures in Television News: An Experiment in Innovative Forms of Journalistic Presentation" in European Journal of Communication 22; 185. 2007.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. The Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. Smith, C. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1962.

Mitchell, William J. The Reconfigured Eye: visual truth in the post-photographic era, MIT Press, 1992.

Mitchell, W. T. J. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Morse, Margaret. Virtualities: television, media art, and cyberculture. Indiana University Press, 1998.

Panofsky, Erwin. Perspective as Symbolic Form. Trans. Woods, C. S. Zone Books, 1991.

Spence, Robert. Information Visualization. ACM Press, 2001.

Notes

[1] Richard Carleton suffered a heart attack during a press conference at the Beaconsfield mine site on the afternoon of May 7 and was pronounced dead on arrival at hospital in Launceston. [^]

Return to Top╗